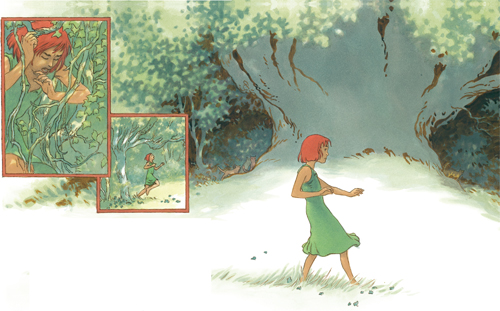

And suddenly she was a girl again. The night and the swamp and the possum witch were all gone. It was the middle of the afternoon and she was running through a part of the woods that had been familiar until she’d followed the deer farther into them. She stumbled, thrown off balance by the sudden switch from four legs to two, but caught herself before she could fall. Her momentum carried her out from under the trees into a meadow.

And not just any meadow, she realized. The buck was no longer in sight, but there in the middle of an expanse of grass and wildflowers was the ancient beech tree where she’d fallen asleep and gotten snakebit.

This time she knew enough not to lie down. No more snakebites for her, thank you very much.

“Hello hello!” she shouted to no one in particular. “I’m my very own self!”

She pulled a few daisies from their stems and tossed them in the air. It was so good to have hands again. She did cartwheels all around the beech tree for the sheer joy of it. When she finally stopped to catch her breath, she leaned against the fat trunk of the beech and looked gingerly around her feet.

That hadn’t been the smartest thing she’d ever done—turning cartwheels when she knew there was a nasty snake somewhere in the grass around the tree. But no matter how carefully she studied the grass and wildflowers, she couldn’t see any sign of the snake.

Didn’t mean it wasn’t there, she thought.

But she had to wonder. The bite. The talking animals. The possum witch.

Had any of that really happened? Or had she fallen into some sort of storybook dream? That made a lot more sense. But if it had been a dream, how had she woken up running? Did people run in their sleep?

She decided it didn’t matter. Not right now. Right now all she wanted to do was see Aunt and have Aunt recognize her.

With a lighthearted skip in her step, she set off for home.

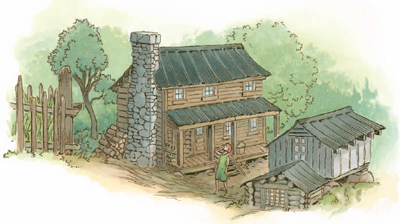

Crossing the creek was easy now that she wasn’t a cat. She ran through the woods, into the meadow, and up the hill. Her heart gave a little happy jump when she saw the roof of the barn, then the springhouse with the corncrib and the smokehouse behind it, and finally the old farmhouse itself.

She wanted to be turning cartwheels again, but they were too hard to do uphill. So she sang instead, a trilling tra-la-la-la-la. She could already imagine Aunt’s face with the look that so plainly said, What’s that silly girl up to now? But she didn’t care because she was almost home again and everything was the way it was supposed to be.

Tra-la-la-la-la!

She saw Annabelle in the paddock and laughed, remembering how in her dream she’d imagined having a conversation with the cow. Cow and squirrel and crow and fox—it was all so silly. And the possum witch? Wherever had she come up with something like that?

“Hello hello, Annabelle!” she called as she skipped by the paddock. “Sorry—no time to talk!”

She laughed again as she made her way to the back of the farmhouse. As if a cow could talk. On the other side of the smokehouse she could hear Henry the rooster ordering the chickens around. She went up the stairs and into the summer kitchen, feet slapping on the wooden floor.

“Aunt!” she called. “Hello hello! I’ve had the strangest dream. You won’t believe how harebrained it was….”

Her voice trailed off when she realized she was talking to herself. Aunt wasn’t in the kitchen. She wasn’t in the parlor, either. Nor was she upstairs.

Had she said she was going to town, or to the Welches’ farm? Lillian couldn’t remember.

She leaned on the windowsill of her bedroom and looked out across the apple orchard, but there was nothing to see. A crow winged from the forest, banking on a breeze before it went gliding down toward the creek. She found herself wondering if it was Jack Crow, then smiled. Jack Crow wasn’t real. He was just another part of her dream.

But the smile didn’t seem to want to stick. Aunt being gone like this was worrisome.

Lillian turned from the window and went back downstairs. She made another circuit of the house before going outside once more. She looked in the corncrib and the smokehouse. She checked in the barn and the chicken coop. She walked past the beehives and up into the orchard, all the way to the family graveyard, then back down the hill again. Following the tree line, she stopped at the outhouse, calling for Aunt before she opened the door to peer in. The only thing inside was a spider, weaving its web in a corner.

“You should get packing,” Lillian told the spider. “Aunt sees you settling in like that and she’ll take a broom to you.”

Aunt…

Lillian felt as though she had a big stone sitting in the bottom of her stomach.

“Oh, Aunt,” she said as she turned away from the outhouse. “Where are you?”

She started back for the house, then changed direction as she realized the one place she hadn’t looked was the small corn patch on the other side of the barn. She picked up her pace, calling for Aunt.

Her heart sank again as the patch came into view. The green corn was only up to her waist. If Aunt had been hoeing weeds between the rows, her tall, bony frame would have been easy to see. But there was no one there, either.

Lillian would have turned away, except just then she saw something odd down one of the rows. A smudge of gingham. Gingham like Aunt’s dress.

She took a step closer, then she was running for where Aunt was lying in the dirt in between the rows of green corn.

“Aunt, Aunt!” she called out.

She wanted to pretend that Aunt was only lying down, having a rest, but she knew something was wrong. Something was terribly wrong. Stalks of corn were bent from where she’d fallen. Some were broken. Aunt lay with her face pressed into the ground, dirt smudged on her face.

Lillian dropped to her knees beside Aunt and gave her shoulder a little push.

“Get up, get up!” she cried. “Oh, please, get up.”

But Aunt didn’t move. And then Lillian noticed the two little marks on her ankle, surrounded by a red inflammation.

Snakebite.

No, no, no!

Surely Aunt had only fainted. In a moment her eyelids would flutter open and she would smile weakly at Lillian.

But no, this… this was different, and Lillian knew it. She was no stranger to death. She’d come across the remains of animals in the woods. She’d seen the cats kill mice and voles, spitting up a few tiny organs when they were done eating. She’d helped Aunt when one of the chickens was going to be dinner.

Lillian’s chest felt like it might burst. This couldn’t be true. Yet here was Aunt, lying gray-skinned on the ground.

She stroked Aunt’s cooling brow and realized that her dream hadn’t been some silly little thing she’d imagined. It had been a premonition. A warning. But it had come too late.

She lowered her head, pressing her face into Aunt’s shoulder.

“Please wake up,” she whispered. “Please, Aunt. I don’t know what to do….”

But she knew Aunt was gone. She cried for a long, long time.

Dusk was coming on when Lillian finally sat up. She sniffled and wiped her nose on the shoulder of her dress. Aunt was stiff now, her skin cold to the touch. Lillian was slow getting to her feet. She seemed to have no strength. All she had was what felt like a huge, gaping hole in the middle of her chest.

Oh, Aunt…

She was twice orphaned now.

Aunt had become her entire family—mother and father and every other relative you could have, all rolled up into one. Lillian didn’t really remember her mother or father. Influenza had taken them when she was only a year old. The sickness had raged through the hills, and there was no rhyme nor reason why so many died, while others, such as Lillian and Aunt, were spared.

Turning away, she shuffled through the rows of corn. When she got to the barn, she pulled an old blanket down from its peg and put it in the wheelbarrow. The wooden wheel rattled in its brackets as she left the barn and returned to the corn patch. But once she got the wheelbarrow in between the rows and into position, she couldn’t lift Aunt onto the wooden slats of its bed. She wasn’t nearly strong enough.

What was she supposed to do now? She couldn’t just leave Aunt lying in the corn patch. What was going to happen? Why did she have to be so small and useless? Poor Aunt.

Kneeling in the dirt beside the wheelbarrow, her arms and shoulders aching from the effort, she started to cry again, but then quickly choked back her tears. If she let herself weep, she didn’t think she’d ever be able to stop. There was still too much to do. She owed it to Aunt.

She sat up and gently laid the blanket over Aunt, then pushed herself to her feet. Her footsteps were heavy as she left the corn patch for a second time. The hole in her chest felt even bigger—like nothing would ever fill it again.

It was almost full night now. She got Annabelle and brought her into the barn. Then she went to the house and got the lantern down from its shelf. Lighting the wick, she went outside. The lantern chased shadows away from her as she took the long path that led down to the Welches’ farm.