Birdsong woke Lillian the next morning. She lifted her head in confusion, trying to figure out where she was, but then it all came flooding back. Her throat closed up and her eyes filled with tears. Sitting up, she wiped at them with a corner of the blanket.

The Welches’ house was quiet. Glancing out the window, she saw that it was still very early. She got up and tiptoed into the kitchen, then out onto the porch. A barn cat jumped down from the railing, startling her. It gave her a long, thoughtful look, then slipped around the corner of the house. Lillian watched it go.

She thought about her strange dream: the circle of cats around the beech tree and the talking animals. The snakebite. She felt vaguely guilty, as though this were somehow her fault, that she should have been the snakebit one.

If only the dream had been real. She’d much rather be trapped in the shape of a cat if it meant that Aunt would still be alive.

She heard the door open behind her. Harlene joined her, putting an arm around Lillian’s shoulders.

“How are you doing, hon?” she asked.

“I…” Lillian had to swallow hard before she could go on. “It… it doesn’t feel real.”

Harlene nodded. “It’s going to be like that for a long time.”

“But how will I manage without Aunt? Aunt was everything.”

“I know. But we’ll take good care of you. I promise.”

This felt all wrong. Aunt took care of her. She and Aunt helped each other.

“I’d better go home,” Lillian said. “I’ve got chores.”

“No, you don’t. Earl talked to the Creek aunts. A couple of their boys are going to look after things for the next few days. We’ll see what happens after that. You can’t be living way up there all on your own, Lillian.”

A shiver crawled up Lillian’s spine. Leave the farm? The thought was unbearable, so she decided to ignore Harlene’s last comment.

“What—what about Aunt?”

“Earl’s gone into town to talk to the preacher. We’ll lay her to rest with your mama and papa, up at the top of the hill. The Creek boys have offered to dig the grave.”

“Where’s Aunt now?”

“Earl said he laid her out in the parlor.”

It had been a relief to let Harlene and Earl take over, but now Lillian felt totally powerless. She was like a leaf caught in an eddy, turning ’round and ’round alongside the shore.

She thought about poor Aunt lying all alone in the parlor.

“Can I go see her?” she asked.

“Of course you can, hon. I’ll go up with you, and we can pick out something pretty for your Aunt Fran to wear. But before we go, I need to see to the livestock.” She cocked her head. “Will you help?”

Lillian nodded. What else could she do?

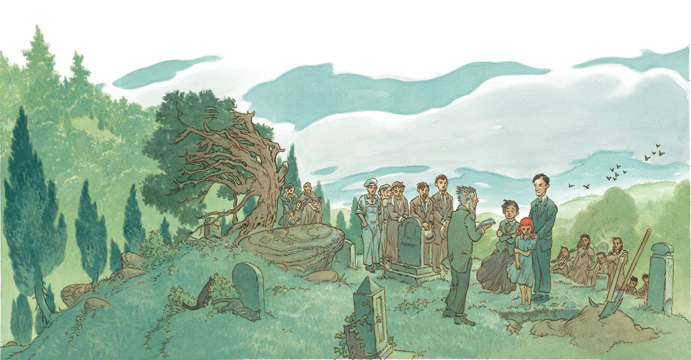

The day they laid Aunt to rest started out sunny, but by the time they’d gathered in the small family plot on the hill above the Kindred farm, the skies had clouded over and threatened rain. Harlene and Earl Welch stood beside Lillian at the graveside. Lillian wore her good dress, and even had shoes on her feet. Preacher Bartholomew stood at the head of the grave, his Bible open in his hands.

A few other townsfolk and neighbors had made the long hike up to the farm. The Mabes, who lived a few farms over. Charley Smith from the general store. John Durrow and his son Jimmy, who grazed their cattle on the lower pastures near the road to town. Agnes Nash, who looked after the town’s library. Humble Johnson, a banjo player who led the dances at the grange.

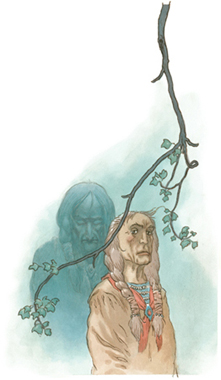

Standing behind them were the extended families of the Creeks—dark-skinned men in buckskin and denim, the women in long, embroidered black skirts, with their hair in braids. The aunts were in front, all except for Aunt Nancy, the oldest. She stood at the edge of the forest, half-hidden in shadow, her somber gaze never straying from Lillian.

At any other time her attention would have made Lillian nervous. No one knew Aunt Nancy’s age. It was said that there’d been a Nancy Creek living in these hills when the white men first came from the east and that she’d still be here long after they were gone. Lillian didn’t know anything about that. She only knew that rowdy and joking though the Creek boys might be, they all grew quiet at even the mention of Aunt Nancy’s name.

She didn’t seem to be alone, standing there under the trees. Lillian thought she could see a dark figure standing behind her, even taller than the stately Kickaha woman, whose head was bowed in sorrow. It was hard to tell, because she only stole glances at them. Sometimes when she looked the figure was there, sometimes it was just Aunt Nancy.

Though the weight of the old woman’s gaze was heavy, it felt light compared to the weight of Aunt’s passing. It had been hard for Lillian to look at Aunt laid out on the parlor table, hard when Samuel and John Creek lifted her into the coffin they’d built from scrap wood they’d found in the barn, harder still when they nailed shut the lid. Every bang of the hammer felt like a nail being punched into Lillian’s chest.

And now the preacher was reading from his Bible, and soon they’d cover the coffin with dirt and Aunt would be gone forever. Her heart was breaking and her mind was spinning. She couldn’t imagine what life was going to be like from here on out.

She couldn’t concentrate on what the preacher was saying because it just felt senseless and empty. But when the brief ceremony was over, she stood tall, just like Aunt would have wanted her to, and accepted the condolences of the neighbors before they left.

The Creeks melted away into the forest, all except for Aunt Nancy, who lifted her hand and beckoned to Lillian with a long, dark finger. Harlene and Earl were talking in earnest to the preacher about something to do with Lillian, but they didn’t even seem to think she should be part of the conversation. Relieved to get away, Lillian circled the grave and went to where Aunt Nancy stood.

The other figure was no longer there—if there ever had been anyone else standing behind Aunt Nancy. Perhaps she’d imagined it. Considering her dream—how real it had seemed—Lillian thought her imagination was much stronger than she wanted it to be.

“I’m sorry for your loss,” Aunt Nancy said. “Your aunt was a good woman, and a good friend to my people. She will be missed.”

Lillian nodded. “I don’t know what I’m going to do without her.”

Aunt Nancy’s dark gaze rested on her for a long moment, and then something shimmered in her eyes, as though she were mildly startled.

“You know it doesn’t have to be this way,” she said.

Her voice seemed different—like it was coming from far away.

“P-pardon me? I don’t understand,” Lillian said.

“I think you do.”

A hand fell on Lillian’s shoulder before she could ask Aunt Nancy what she meant. She turned to see Earl behind her.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I was just…” Lillian began, turning back to Aunt Nancy, but there was no one there now. Talking to myself, she thought. “I was wondering why they all left so quickly,” she finished. “The Creeks, I mean.”

“You don’t ever want to try to figure them out,” Earl said. “It’ll just make your head hurt. They may have been your aunt’s friends, but they’ve always been a real strange bunch.”

“I guess….”

“Still, it was good of them to come by to pay their respects. And they’ve been a big help these past couple of days.”

Lillian nodded.

Earl squeezed her shoulder.

“Come on,” he said, steering her back toward the grave, where Harlene and the preacher waited. “We’re going home now.”

Home? Lillian thought. The Welches’ farm wasn’t her home. She glanced around, her heart filled with affection and sorrow. She was the last Kindred. This was her family home. But she let him lead her away.

As they followed the path back to the Welches’ farm, Lillian trailed after the others, holding her shoes in her hand. She paused at the edge of her little family graveyard and turned to look back to the edge of the woods where the Creeks had stood. Something stirred in the undergrowth, and then Big Orange came out onto the grass. A half dozen other cats followed, with Black Nessie bringing up the rear. They sat in a ragged line, gazing in her direction. Lillian had the funny feeling that they were paying their respects, too.

She lifted a hand to them, but they didn’t move. They were like a line of solemn little statues.

“Lillian?” Earl called.

At the sound of his voice the cats vanished like ghosts back in among the trees.

“I’m coming,” she said.

As she followed the Welches and the preacher, she found herself thinking about what Aunt Nancy had said.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

What had she meant?

Lillian worried the words forward and back as they made their way down the hill.