The commanders, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (next). They were tough, professional, determined men who carried immense responsibilities, as can be seen in the set of their jaws. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The commanders, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (next). They were tough, professional, determined men who carried immense responsibilities, as can be seen in the set of their jaws. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

(EISENHOWER CENTER)

A prayer service on a landing craft, June 5, 1944. Statistically, every one of these men was going to get wounded or killed before victory was attained. (WIDE WORLD)

Eisenhower at Le Havre, France, February 22, 1944, greeting reinforcements coming from England. He always established eye contact with his boys. (U.S. ARMY)

Ike with the 101st Airborne, dusk, June 5, 1944, just before the paratroopers loaded up for their flight over the Channel. Lt. Wallace Strobel wears a card around his neck carrying the number of his plane, 23. Pvt. Sherman Oyler (center), his head above Ike’s thumb, wore the same uniform fifty years later at a celebration of the anniversary of D-Day in Abilene, Kansas. Strobel was also there, but not in his uniform, which no longer fit. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Ike and Monty observe armored maneuvers before D-Day. Their concentration is complete. (UPI/BETTMANN)

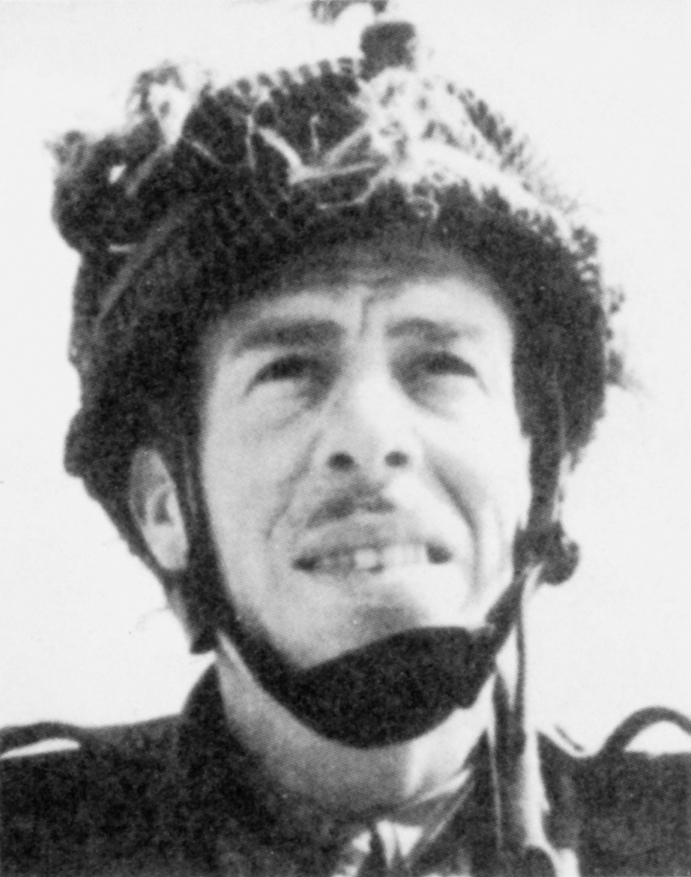

Pvt. David Webster, a Harvard English lit. major in 1942, a member of Easy Company in 1943, here seen in Holland in September 1944. (HANS WESENHAGEN)

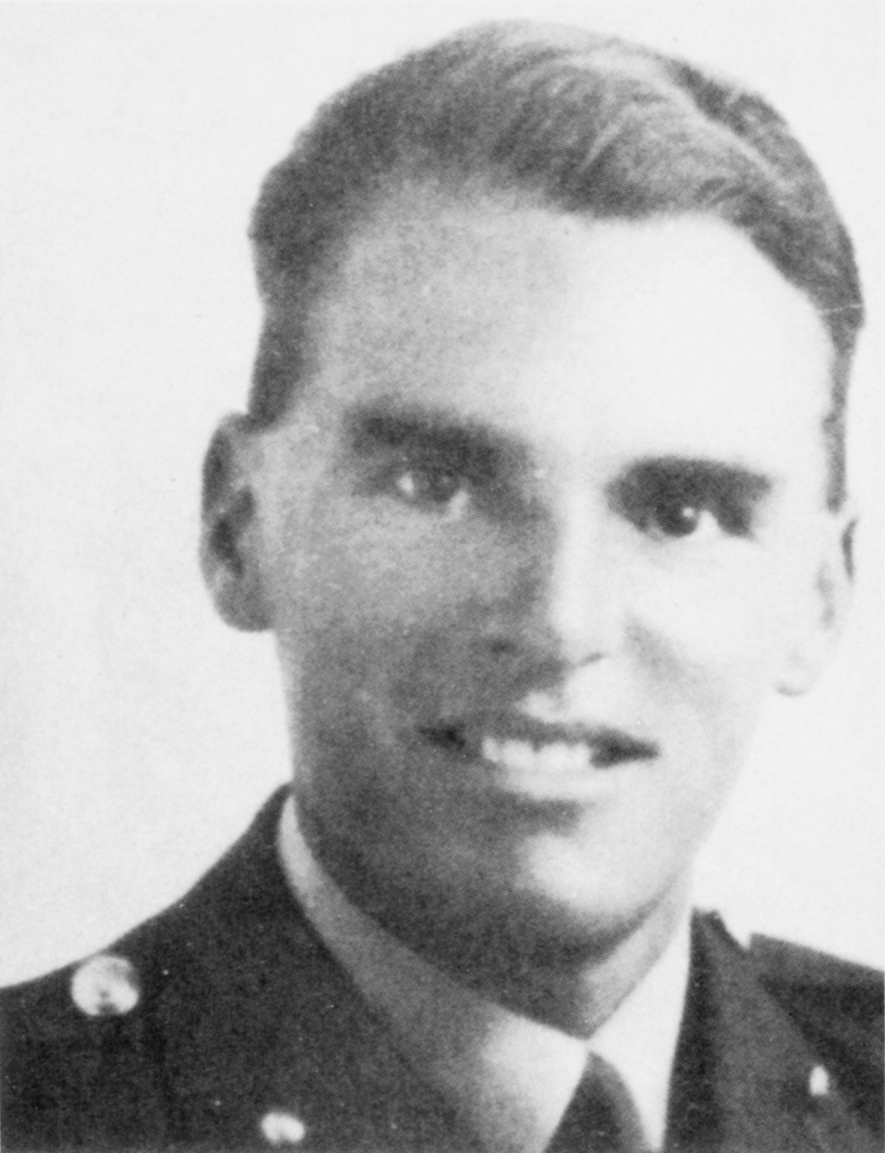

Lt. Richard Winters in training in the States, 1943. He was a platoon commander in Easy Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, just out of college. (FORREST GUTH)

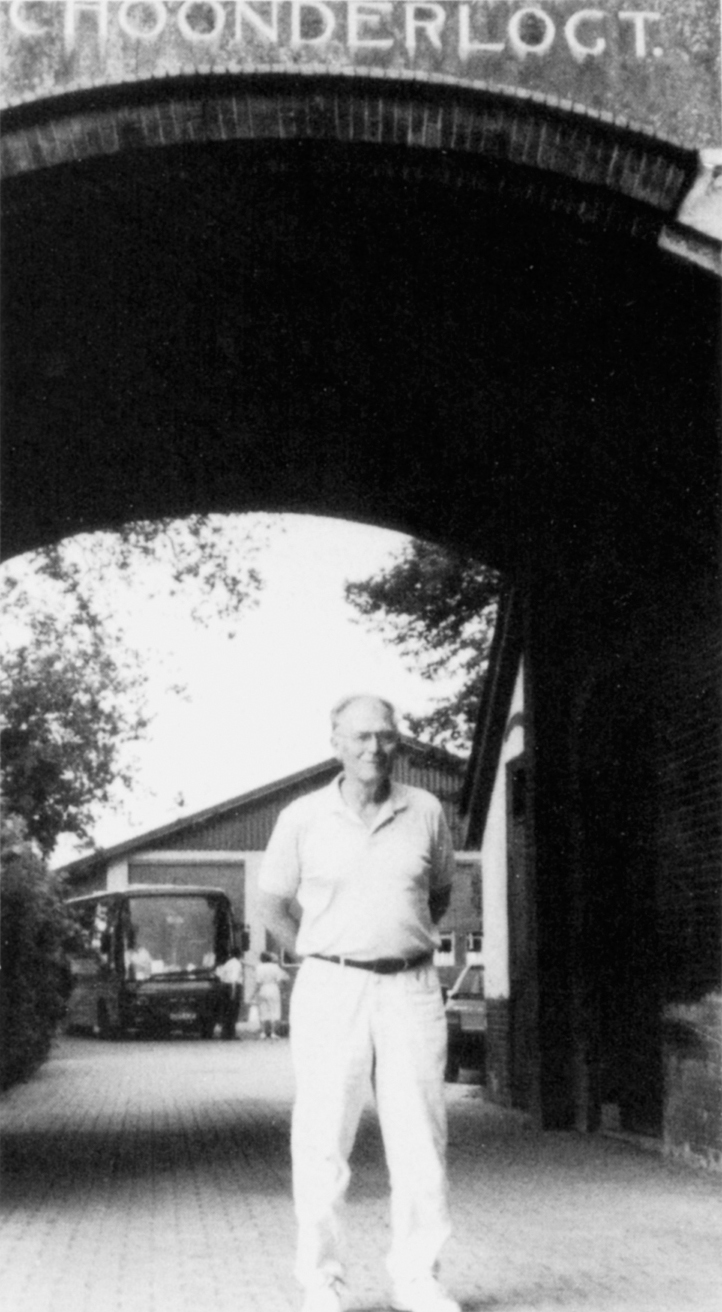

He is under the same gate in 1991, looking as if he could pick up right where he left off forty-seven years earlier. (HOLLIS ANN HANDS)

Captain Winters, by now Easy Company’s commander, in Holland, October 1944. He rose to become the CO of the 2nd Battalion, 506th PIR. (AL KROACHKA/ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The German defenses began at the low tide line (here German troops run for cover as an Allied plane flies low over the beach) (IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM)

Rommel had a half-million of these obstacles in place, along with “Belgian gates,” which were topped with mines and were underwater at high tide (these were piled up by American bulldozers on Utah Beach, June 8). (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

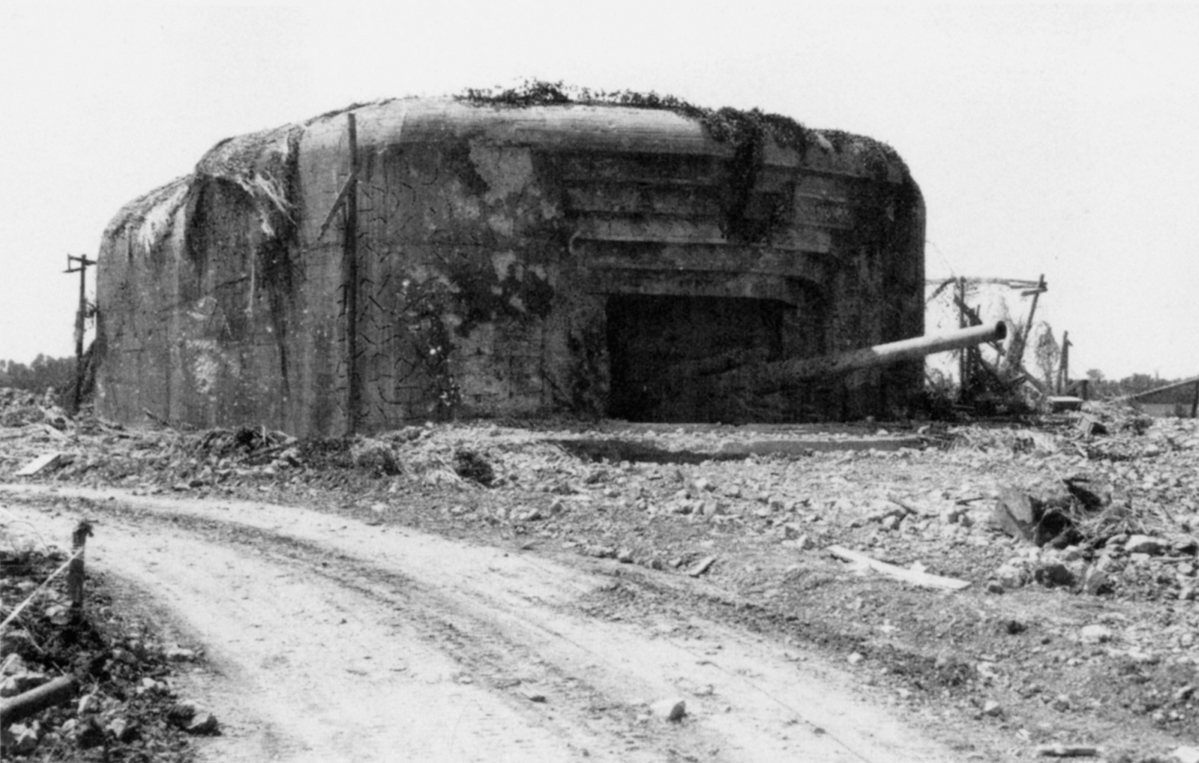

Ashore, fortified positions with steel-reinforced concrete walls as much as thirteen feet thick held 105mm cannon. (U.S. COAST GUARD)

The Higgins assembly line in New Orleans, where Andrew Higgins, the designer and producer of the landing craft, vehicle personnel (LCVP, popularly known as the Higgins boat), built more than 20,000 of them. (EISENHOWER CENTER)

American troops got to England in every kind of ship imaginable. The lucky ones rode on the Queen Mary, shown here in mid-1944 during a lifeboat drill. (WIDE WORLD)

Landing craft at Southampton, June 1, 1944, part of the enormous buildup in southern England for the invasion. These are landing craft, tanks (LCTs) and landing craft, headquarters (LCHs). (IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM)

American landing ship, tanks (LSTs), oceangoing vessels, at Brixham loading up on May 27. Altogether there were more than five thousand landing craft and ships of all types that participated in the invasion. (WIDE WORLD)

Maj. John Howard, CO of D Company, a part of the gliderborne Ox and Bucks Regiment, 6th Airborne Division. His company inaugurated the battle at 0016 hours, June 6, when the gliders touched down at Pegasus Bridge over the Orne River Canal.

Lt. Den Brotheridge, one of Howard’s platoon commanders and the first Allied officer killed on D-Day.

GIs line up for cigarettes just before loading up on the landing craft. One soldier said, “No thanks, I don’t smoke.” “You might as well take them,” the quartermaster replied, “because by the time you get where you’re going, you will.” He was right. (WIDE WORLD)

Unidentified troops in a Higgins boat approaching Omaha Beach, about mid-morning, June 6. When the ramp went down, these men became visitors to hell. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The first waves of GIs at Omaha were hit by a tremendous barrage of machine-gun fire, rifle bullets, 88mm and 75mm cannon, exploding mines, mortars, and hand grenades. A Company of the 116th Regiment, 29th Division, was the first ashore. It took more than 90 percent casualties. Here a shell-shocked 29th Division soldier collapses by the chalk cliff below Colleville. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Men from the 16th Regiment, 29th Division, under the cliff below Colleville. At this point, about 0800, the assault plan at Omaha was dead, and the troops—who had lost their weapons in getting ashore—were leaderless and dispirited. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Wounded men from the 1st Division at Omaha Beach. Medics, universally acknowledged to be the bravest of the brave, had patched them up as best they could, but no amount of medical aid could take away what they had seen and experienced that morning. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Survivors from a destroyed Higgins boat are helped onshore. This may have been the only battle in history in which the wounded were brought forward, toward the front line, for first aid from the medics. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Men from the 4th Infantry Division moving ashore at Utah Beach, late afternoon, June 6. The opposition at Utah was relatively slight; for the 4th Division, the visit to hell began on June 7 and didn’t end until May 1945. (U.S. COAST GUARD)

Light opposition doesn’t mean no casualties; here medics give first aid to wounded 4th Division troops at Les Dunes de Madeleine, Utah Beach. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Robert Capa of Life magazine went in with the second wave at Easy Red sector, Omaha Beach, with E Company, 16th Regiment, 29th Division. He took 106 photos, got off the beach and back to Portsmouth late on June 6, then took the train to London and turned in the film for development. The darkroom assistant was so eager to see the photos that he turned on too much heat while drying the negatives. The emulsions melted and ran down. Only eight photos survive and they have a grainy quality to them. Capa was furious; he took pride in shooting clean and sharp. They became the best known of all D-Day photographs. Here are two of them. (WIDE WORLD)

(WIDE WORLD)

The cliff at Pointe-du-Hoc. The rangers climbed it in the face of fierce resistance. Returning to the scene ten years later, the ranger CO, Col. James Earl Rudder, looked up, scratched his head, and asked a reporter, “Will you tell me how we did this?” (COURTESY OF MRS. JAMES EARL RUDDER)

A landing craft, tank (LCT) brings out wounded assault troops from Omaha Beach, June 7. They were taken to LSTs serving as hospital ships, then to England. The medical team, from the medics to the hospital ships to the hospitals back in England, did a magnificent job. (U.S. COAST GUARD)

“For you the war is over,” and these German POWs—officers and enlisted men on board an LST headed away from Normandy and toward England—couldn’t be happier. (U.S. COAST GUARD)

Old men and boys made up much of the German army manning the Atlantic Wall. These kids look as if they have not even reached their teens. They should have been spanked, not shot. (IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM)

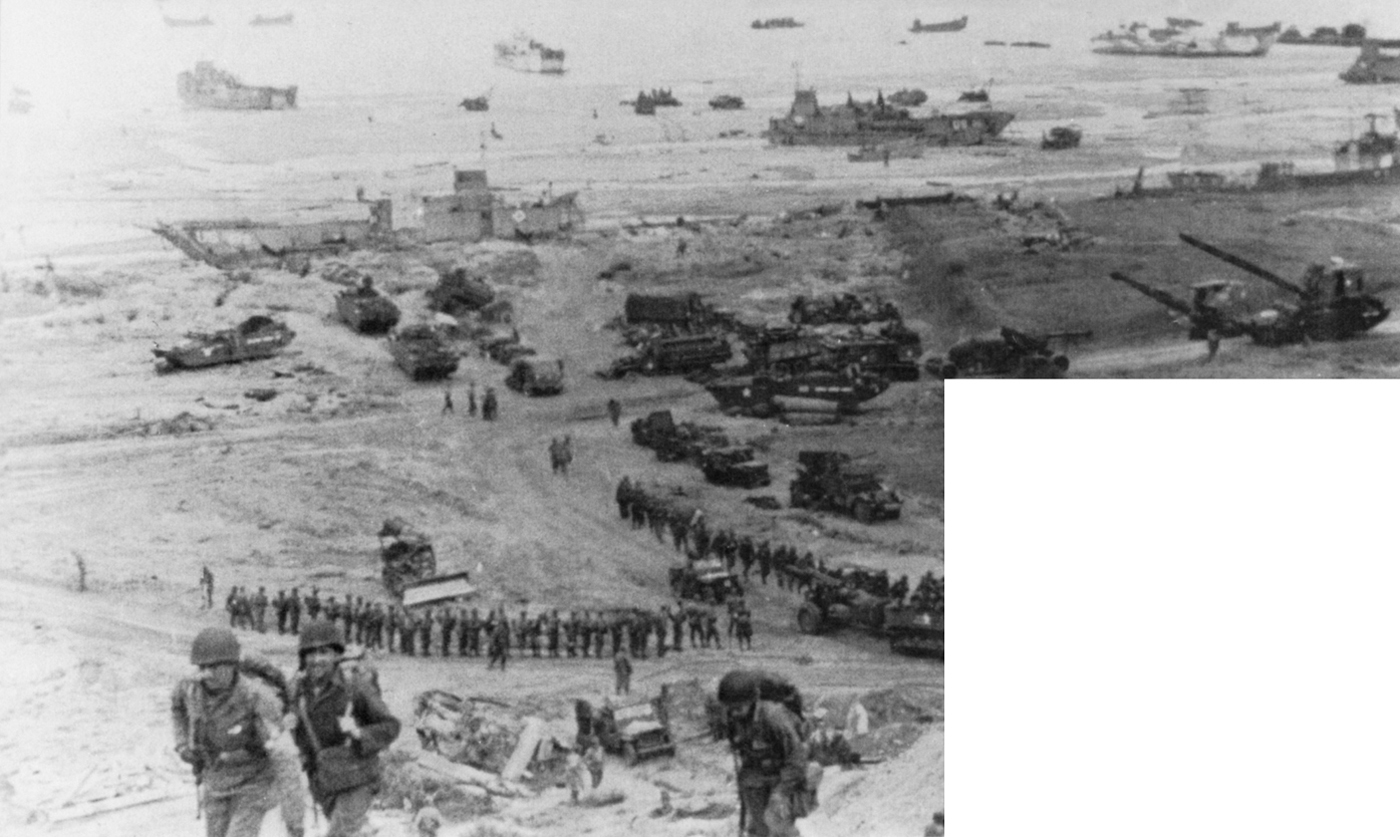

The end of the day at Omaha Beach. American men and equipment coming ashore in staggering numbers. One pilot thought, as he looked down on this scene on June 6, that Hitler must have been mad to think he could beat the United States. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

(U.S. COAST GUARD)

A German soldier lies dead outside a machine-gun emplacement he so vainly defended at Les Dunes de Madeleine, Utah Beach, June 6. He was almost surely running from the emplacement when he got shot; he was probably trying to surrender; whether a GI or his German sergeant shot him cannot be said. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

A young GI wants to see the papers of two even younger Germans, Utah Beach, June 7. Hitler was certain that his youngsters, raised in the Hitler Youth, would outfight the American kids raised in the Boy Scouts. Hitler was wrong. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Easy Company, 506th PIR, hams it up for the cameras on June 7 in the village square of Ste. Marie-du-Mont, which the company liberated on June 6, in the process knocking out a battery of German 105mm cannon.

Pvt. Forrest Guth in a captured German helmet; (WALTER GORDON)

Pvts. John Eubanks and Walter Gordon display the Nazi flag they seized as a souvenir; (FORREST GUTH)

Pvts. Guth, Frank Mellet, David Morris, Daniel West, Floyd Talbert, and C. T. Smith of Easy Company pose with three infantrymen from the 4th Division (back row) who had come in from Utah Beach. (WALTER GORDON)

A part of the continuous stream of men and equipment sailing from England to France, June 7. In the background, a rhino ferry loaded with ambulances eases toward the beach. They kept coming, without pause, for eleven months. (U.S. COAST GUARD)

The men of Easy Company in the square at Ste. Marie-du-Mont meet some local belles; the girls have eyes only for the GIs, while the older residents of the village pose for the cameraman. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Normandy, July 6. A captured German sits on the side of his vehicle, practically ignored by the GIs, who are more interested in the intricacies of his machine pistol. The hedge growing out of the stone wall gives some idea of what superb defensive positions the Germans had available to them. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Unidentified American troops moving into the battle in the hedgerow country. This is not particularly heavy growth; in many cases the treetops met over the sunken lanes. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The first lesson for infantrymen is to learn to love the ground.

As his buddies keep watch, a GI takes a break to wolf down his K-rations—biscuits and cheese. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Two GIs from the 4th Division, in combat since D-Day, catch some rest. They have the necessities of war surrounding their foxhole: ammo clips, hand grenades, water, rations, and bandages in their musette bags. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

A mortar crew from the 35th Infantry Division at work. The GI on the phone is calling out the adjustments from a forward observer. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Normandy suffered terribly. This is the village of Cerisy-la-Salle, July 25. Sgt. David Weiss appears to be telling the little girl—the only person alive in the village—that it is going to be OK. I love this photo, which seems to me to sum up the essential quality of the GI. He came to liberate, not to terrorize. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. Curtis Culin, of Cranford, New Jersey, in Normandy, July 30. Culin exemplified the citizen soldier: a prewar mechanic, he was one of the men responsible for the rhino, equipment that, when welded to the front of his Sherman tank, made it possible for armor to break through the hedgerows and provide fire support for attacking infantry. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

GIs outside the German placement office in Argentan, France, August 20, celebrate putting it out of business. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

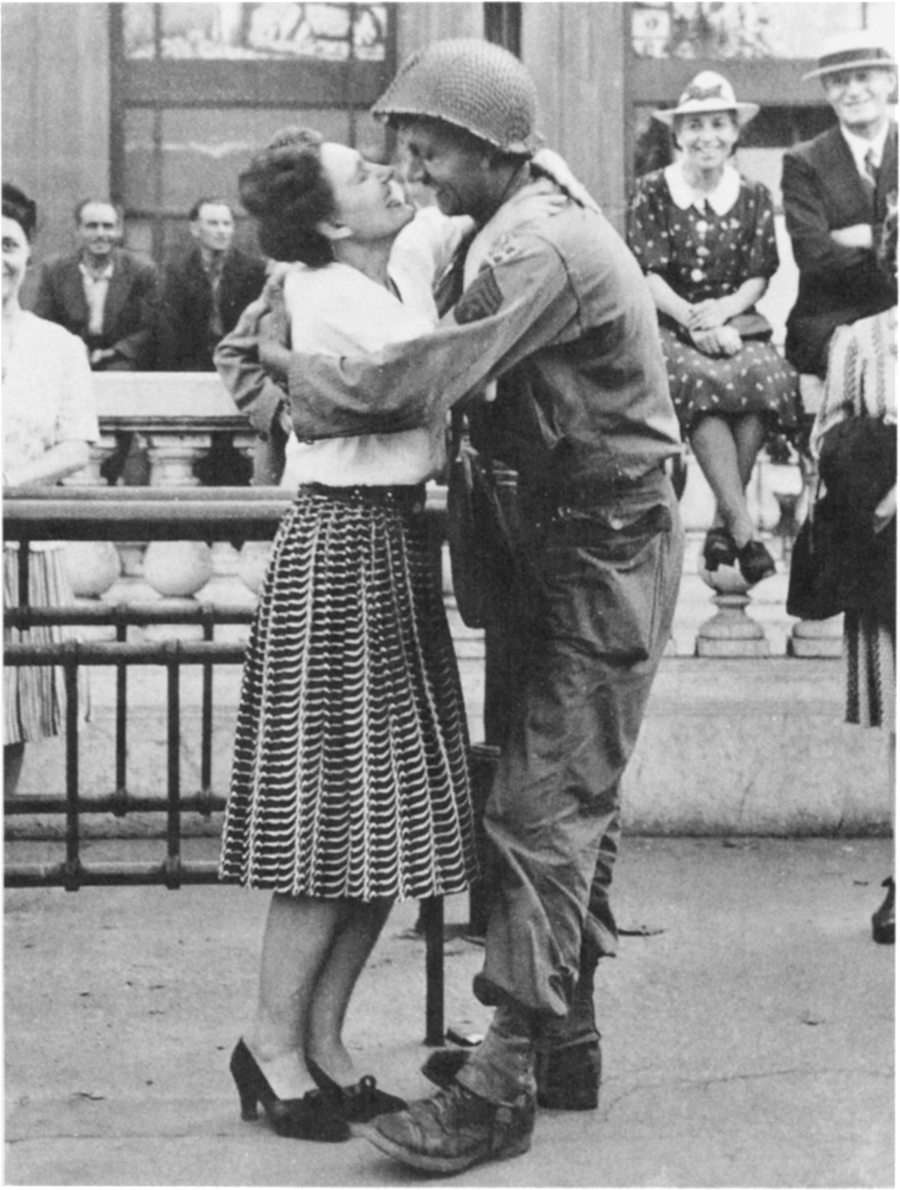

Paris, August 26. Sgt. Kenneth Averill of the 4th Division gets a welcome. The old folks beam their approval. The liberation of the city set off one of the great parties of all time. Unfortunately for the men of the 4th Division, they didn’t get to participate—they marched through the city and back into battle the same day. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Hotel Majestic, Paris, August 26. The hotel had been a German occupation headquarters; now it was a temporary POW cage. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The Hurtgen in 1944 had a marked resemblance to the wilderness in Virginia in 1864—a terrible place to be, much less to have to mount an infantry offensive. Here Pvt. Maurice Berzon, Sgt. Bernard Spurr, and Sgt. Harold Glessler take a break. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The Hurtgen was also a terrible place to have to defend, as the face of this German POW, captured on December 12, reveals. An unidentified GI from the 9th Division is doing the interrogation. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The Third Platoon, Easy Company, 506th PIR, loads into ten-ton trailers at Mourmelon, France, on the afternoon of December 18. The Germans had broken through the American lines in the Ardennes. Short on food, ammunition, and winter clothing, Easy still had to get to Bastogne before the Germans. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. Carwood Lipton in his foxhole outside Bastogne. Easy Company was in this position for nearly a month, fighting on the defensive, hurling back everything the SS Panzer divisions could throw at them, enduring the prevailing cold. (FORREST GUTH)

Capt. Ronald Speirs, who took command of Easy in mid-January and led it on an offensive into the village of Foy. Speirs was even tougher than he looks, an outstanding rifle company commander, highly respected by the men. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. Carl Butler, 1st Division, Belgium, December 22, peers out from his armored car. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Two teenage boys a long way from home. The German soldier is better dressed for the conditions than his American guard. He was also luckier—he had made it safely into POW status and was headed toward the rear, and eventually to the United States, where he would do farm labor until the war was over. His guard had to carry on. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

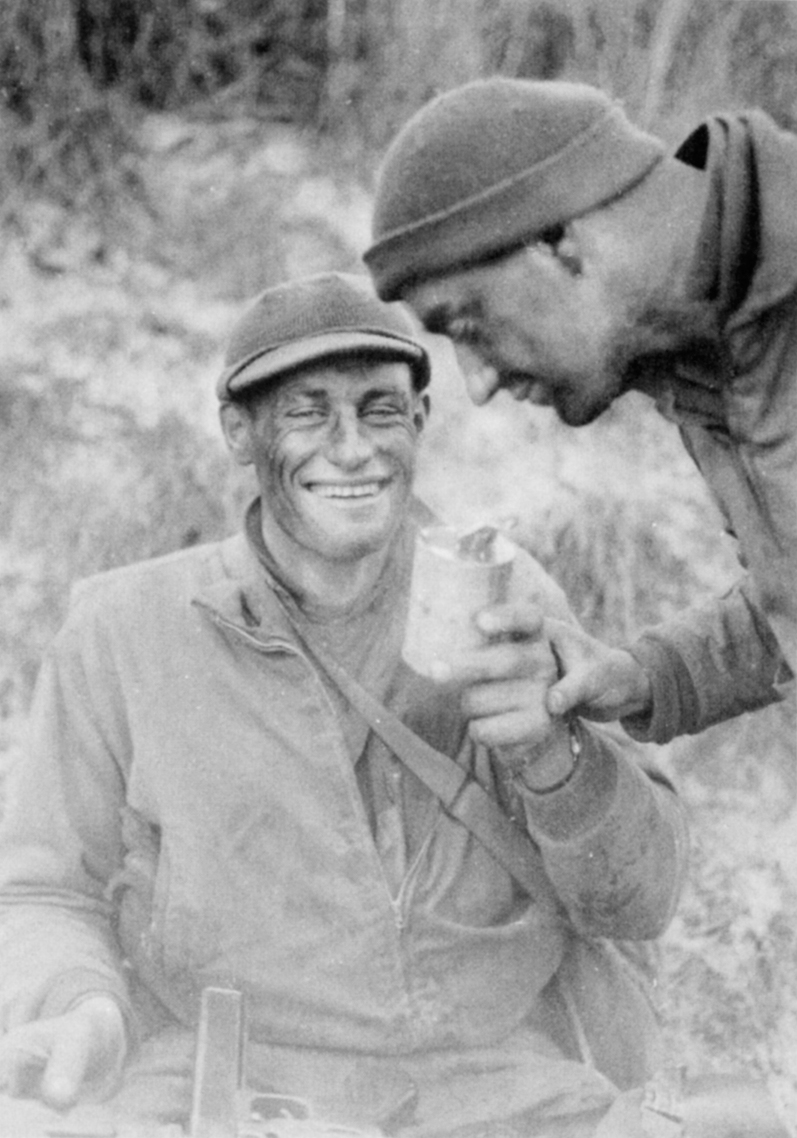

Two unidentified GIs ham it up with their cold rations for the photographer, Soy, Belgium, December 26. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. Joseph Arnaldo, an infantry squad leader, comes off the line after ten days in the Ardennes, December 30. He has what the soldiers called the thousand-yard stare. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. William Howard, 79th Division, in the Scheibenhardt area, January 2. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The January cold was intense. By February, mud was the problem. The tension was always there.

Sgt. Joseph Holmes, 35th Division, Belgium, January 10. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Pvt. Morton Frenberg, 8th Division, February 24. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Medics at work on an unidentified wounded GI. In training camp, the medics were derided. In combat they were called Doc and universally praised. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Medics helping an unidentified GI to the aid station. The GIs were convinced there was an army regulation against dying if you made it alive to the aid station. The GI on the left has all the look of a just-arrived replacement, including new boots. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

At Istres Airport near Marseilles, July 15, 1944, three crewmen pose beside “Rum Dum,” a B-17 that had the record for combat missions at 101. The plane was then put to work flying the wounded to England. The B-17—plane, pilots, and crew—had a reputation for toughness and durability. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The payoff for air superiority. Whenever a German soldier heard a plane overhead, he ducked. When a GI heard one, he looked up and smiled. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

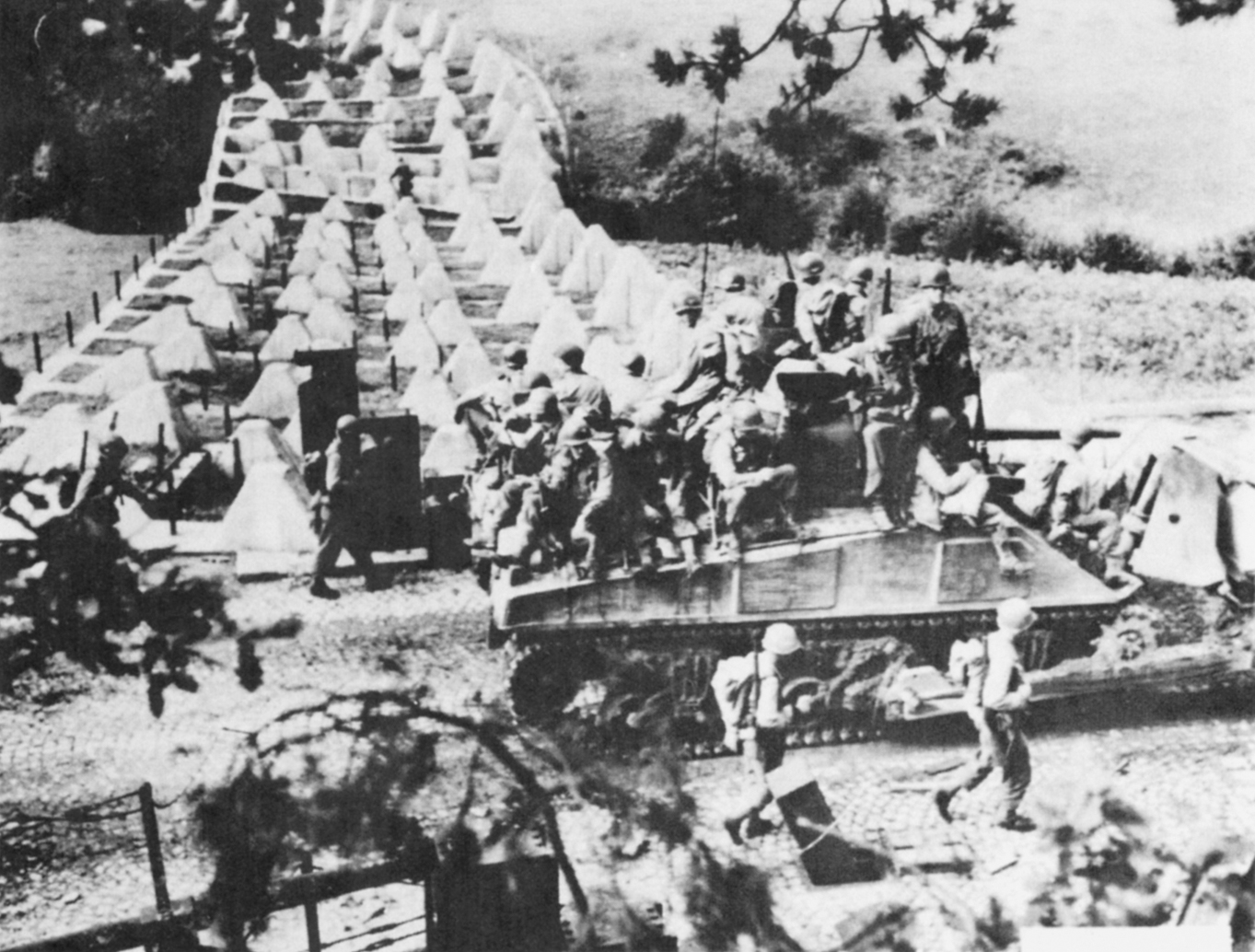

The 9th Infantry Division, afoot and riding the back of a tankdozer, passes through the dragons’ teeth in the Siegfried Line, September 1944. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Two American paratroopers on the attack, despite the German barrage, in Operation Market-Garden, Holland, September 1944. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

A Replacement Depot, or Repple Depple, in Luneville, France, October 12. Boredom and a sense of isolation were the dominant mood in these depots, which the GIs hated, with good cause. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Aachen, Germany, October 15. In a battle that did precious little good for either side, the ancient city was all but destroyed. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Sgt. Mike Ala, 4th Infantry Division, on the radio in the Hurtgen Forest, November 18. Communication by telephone was more secure, but less dependable, because the wire (in the spool behind Ala) kept getting cut by the shells. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

In the Hurtgen, December 9, German prisoners are being escorted to the rear by a GI from the 9th Division. The photo has the Bill Mauldin quality of sheer misery, for both sides. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

More Willie and Joe photographs from the god-awful Hurtgen. Here GIs from the 9th Division move up for an attack later that day. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Jungersdorf, Germany, December 12. GIs from the 9th Division with a bag of captured Germans. You can distinguish the victors from the vanquished by the smiles on the victors’ faces. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

On December 16, 1944, the German army struck out in its last great offensive of the war—an offensive on a greater scale than the one it had launched in the same area in May 1940. The Germans had been retreating since July. Going over to the offensive raised morale, as these captured German photographs, taken on December 17, the second day of the Battle of the Bulge, demonstrate. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

(U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Belgium, December 25. The urge to attend services and pray was overwhelming. Every man in the battle, German or American, who could went to church, to sing the same song, “Silent Night.” (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Christmas 1944. In a manger six hundred meters from the German lines, men from the 94th Division dry out and count their blessings. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The GIs were surprised. Some were shocked. Some surrendered. Some ran. But enough stayed to do their duty. On December 17, GIs from the 2nd Infantry Division crouch in a ditch during a German shelling, ready to fight back when the German infantry began to attack. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Men of the 90th Infantry Division wait out a shelling in Wiltz, Luxembourg, January 9. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

For the GIs the way home led east. They couldn’t get back to the States until Germany quit. So they sucked it up and moved out. Here men of I Company, 84th Division, get on with it. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Belgium, January 5. Two 2nd Infantry Division men get ready for whatever might come. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

To get a look at the enemy you had to expose yourself—but you kept the exposure to a minimum. Here Cpl. Irvin Kruger, 4th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Beffe, Belgium, spots German snipers. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Pvts. James Acosta and Kenneth Horgan, 3rd Armored Division, in the Ardennes, January 14. They have their bazooka handy in the event of a German armored attack. Clear days with sunshine meant colder nights, but they also meant the U.S. Army Air Force could fly, a blessing to the ground troops. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Whatever the conditions, the GIs had to have foxholes. Here Pvt. Joe Fink digs his with a pickax, January 30, Wirtzfeld, Belgium. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Horsbach, France, February 2. Pvt. Vincent Wenge, 70th Division, bails out his foxhole after a thaw. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Kerpen, Germany, February 28. Mortar crews fire in close support of advancing infantry. By this time, the GIs were attacking all along the line. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Men from the 1st Infantry Division in Gladbach, Germany, March 1. The Big Red One had been in combat since D-Day—and before that it had fought in North Africa and Sicily. Virtually all the men in this photograph were replacements, most of them coming in during and after the Battle of the Bulge. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

By March, the U.S. Army in Northwest Europe was made up of a handful of veterans in their early twenties and lots of replacements who were eighteen and nineteen years old. They either got wounded or killed, or they matured into veterans in a hurry.

Two GIs who look to be 1944 high school graduates work at their 105mm cannon outside Erp, Germany, March 6. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

GIs in action in street fighting in Koblenz, March 18. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The look of victory. Gens. Eisenhower, Patton, Bradley, and Hodges at Hodges’s First Army HQ near Remagen, Germany, March 25, 1945. The previous day American troops had broken out of their bridgeheads to begin the final drive through Germany. (U.S. ARMY)

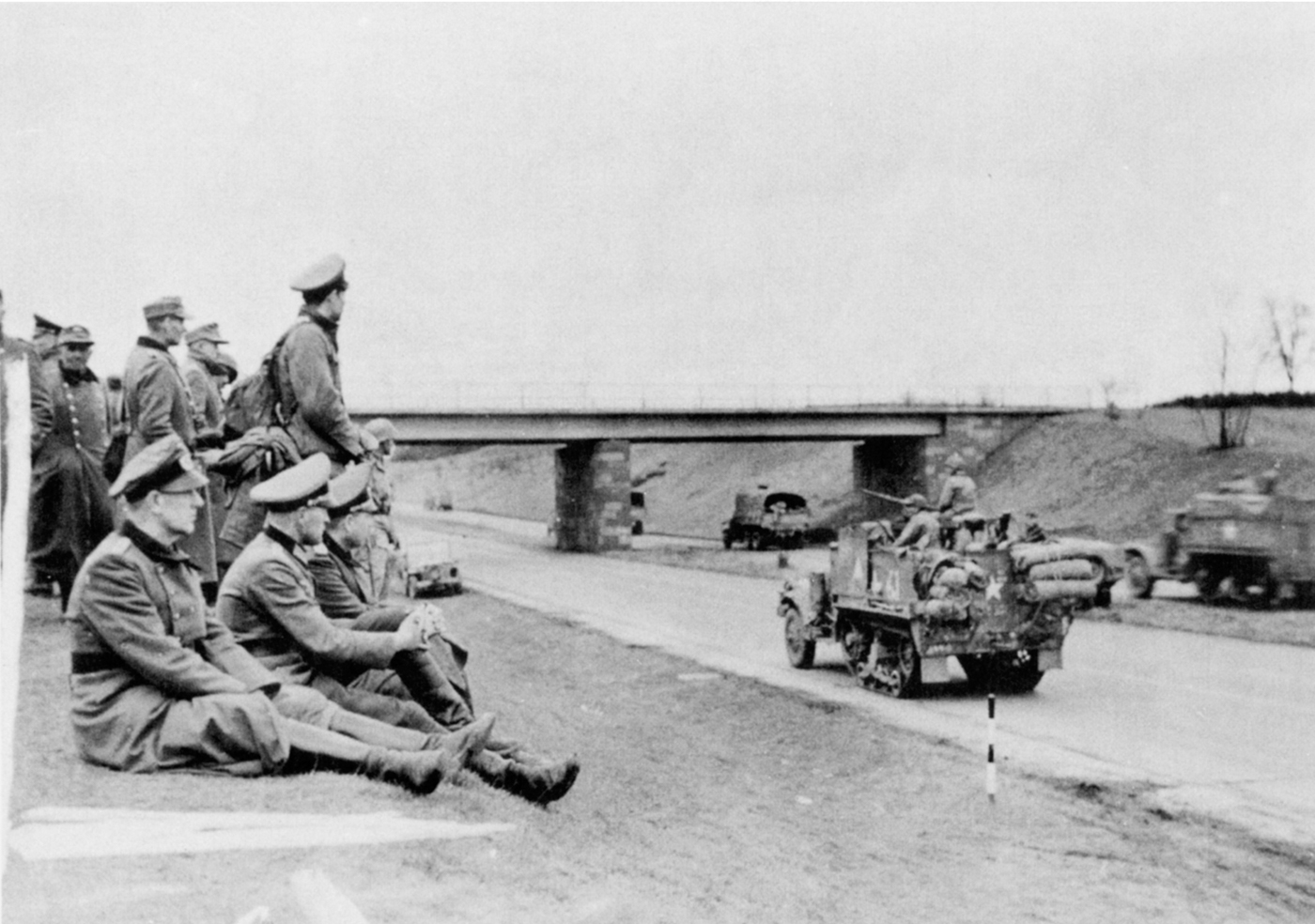

German officers wait along the autobahn near Giessen, Germany, watching vehicles of the U.S. 6th Armored Division moving up to the front. As one captured German officer put it, “We had never seen how a rich man makes war before.” (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

The most welcome sight in the world for these prisoners in Dachau was the appearance of GIs. They ran up a homemade American flag to welcome their liberators, men of the 45th Infantry Division. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

Cpl. Larry Mutinsk, 45th Division, hands out his last pack of cigarettes to prisoners in Dachau. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)

By March 29, 1945, the U.S. Army was pouring across Germany. These German POWs, marching west to their POW camps along the Rhine River, were astonished at the number of trucks, tanks, half-tracks, and vehicles of all kinds their enemy possessed. But in the end, what beat the German army was not so much equipment as men. The GIs had proved themselves; here was the fruit of their victory. (U.S. ARMY SIGNAL CORPS)