The Battle

in the State

Courts

New York's real estate men lost no time launching an attack on the emergency rent laws. On October 1, just a few days after the September laws went into effect, the Board of Governors of the Real Estate Board held a special meeting at which it decided to test what it viewed as the state legislature's misguided decision to suspend the fundamental rights of the city's property owners. As counsel, the board retained George L. Ingraham, a former presiding justice of the First Department of the New York Supreme Court's Appellate Division, which covered Manhattan and the Bronx, and now a partner in a leading New York City law firm. At the same time a group of apartment house owners, brokers, and managers held a meeting at which they formed the Real Estate Investors, Inc., sometimes referred to as the Real Estate Interests, Inc., an organization whose sole purpose was to test the constitutionality of the rent laws. As counsel, it retained Francis M. Scott, another former New York Supreme Court judge and now a partner in a prominent New York City law firm too. The Real Estate Investors, Inc., soon joined forces with the Real Estate Board, as did the Apartment House Owners and Builders Association and other property owners’ groups. If all this were not enough, some New York landlords were planning to challenge the constitutionality of the emergency rent laws on their own.1

Most New York real estate men believed that the emergency rent laws would not withstand judicial scrutiny. According to A. C. McNulty, counsel to the Real Estate Board, and F. S. Bancroft, vice president of Pease & Elliman, many of these laws, especially chapters 942, 944, and 947, violated one or more provisions of the U.S. and New York State constitutions. The members of the Brooklyn Real Estate Board agreed. Even some legislators had doubts about the constitutionality of the emergency rent laws, noted the Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. The Real Estate Investors, Inc., pointed out that no less an authority than Charles Evans Hughes, former justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (as well as former governor of New York and Republican presidential candidate), had rendered an informal opinion that the laws were unconstitutional. But many other New Yorkers believed that the rent laws would survive a constitutional challenge. “I have no fear as to the constitutionality of [the] measures enacted at the emergency session,” declared Arthur J. W. Hilly, chairman of the Mayor's Committee on Rent Profiteering. With the possible exception of chapter 947, “there was nothing in the new laws that was not absolutely consistent with every principle of Anglo-Saxon justice,” contended Harold G. Aron, professor of Real Property Law at New York Law School. His committee had done its utmost to draft laws that “would hold water,” said Senator Charles C. Lockwood, even shelving several bills that might have curbed rent profiteering out of fear that they would be held unconstitutional.2

But many lawyers held that the issue was less clear-cut. As Aron pointed out, the problem was that the emergency rent laws consisted of more than twenty different acts, of which half were enacted at the regular session and half at the special session. The less stringent ones were almost certain to pass judicial muster. But the more draconian ones raised serious constitutional issues. A case could be made that these laws impaired the contractual obligations of landlords and tenants, which was barred by article 1, section 10 of the U.S. Constitution (as well as a similar provision of the New York State Constitution). A case could also be made that these laws deprived the landlords of property without due process of law and denied them the equal protection of the law, which was prohibited under the Fourteenth Amendment (and another provision of the state constitution). In light of the current emergency, it was possible that the rent laws would withstand judicial scrutiny. It was also possible that they would be held unconstitutional. It was even possible that the state courts would rule one way and the federal courts another. As of October 1920 the situation was so fraught with uncertainty that the constitutionality of the New York rent laws “must be regarded as still open,” wrote Henry H. Glassie, a prominent Washington, D.C., lawyer who would later appear before the U.S. Supreme Court in defense of the Ball Rent Act, which regulated rents in the District of Columbia.3

Glassie knew what he was talking about. As of October 1920 there was good reason to believe that the emergency rent laws would survive a constitutional challenge. Starting in May, several landlords had filed suit for nonpayment of rent and, when the tenants responded that the rent was unreasonable, argued that the April laws were unconstitutional. To the dismay of most landlords, the courts were not swayed by this argument. In some cases they sidestepped the constitutional issue. In Paterno Investing Corporation v. Katz, which was handed down in June, Judge Irving Lehman ruled in favor of the landlord on the grounds that the April laws were not retroactive, but also insisted that the constitutionality of the laws was not “in any way involved in the decision.” And in Blek v. Davis, which was decided in July, the First Department of the Appellate Division “left the [constitutional] question open,” to quote Aron. The courts upheld the April laws in other cases too. In Seventy-Eighth St. & Broadway Co. v. Rosenbaum, which was decided in May, Judge Frederick J. Spiegelberg ruled that chapter 136 did not violate article 1, section 10 of the U.S. Constitution. And in Kuenzli v. Stone, which was also handed down in May, the Appellate Term of the Second Department upheld a ruling of a Queens municipal court judge in favor of the tenant. Writing for the court, Charles H. Kelby rejected the landlord's argument that chapter 137 was unconstitutional. Since the state legislature had created summary proceedings, it was within its power to modify or even abolish it.4

But as of October 1920 there was also good reason to believe that the emergency rent laws would not survive a constitutional challenge. For one thing, the September laws were much more onerous than the April laws—and thus much more vulnerable to attack. To give one example, the April laws changed the rules governing summary proceedings, but not the rules governing ejectment, the other action by which a landlord could recover his property. Indeed, in Kuenzli v. Stone, Kelby stressed the point that under the April laws “owners of real property still have the remedy of an action in ejectment.” But under chapter 947 of the September laws the legislature suspended actions in ejectment in all but a few exceptional cases until November 1, 1922. For another thing, the Washington, D.C., Court of Appeals, one of the country's most influential federal courts, had recently held that two measures that regulated rents in the nation's capital were unconstitutional. In Willson v. McDonnell, which was decided in December 1919, it struck down the Saulsbury Resolution, which Congress had adopted in May 1918 to prevent Washington landlords from raising rents and evicting tenants until World War I was over. And in Hirsh v. Block, which was handed down six months later, the Court of Appeals ruled against the Ball Rent Act. Passed by Congress in October 1919, this act superseded the Saulsbury Resolution, imposed rent control in the capital, and set up the District of Columbia Rent Commission to implement it.5

With the stakes so high, both sides assembled a team of top-notch lawyers. In addition to retaining Ingraham and Scott, the real estate interests brought in five veteran real estate lawyers to work with them. Assuming that the case or cases would be taken up to the New York Court of Appeals, the state's highest court, and the U.S. Supreme Court, the real estate interests enlisted the help of Louis B. Marshall, who was called “a great constitutional lawyer” by Julius Henry Cohen, a prominent attorney who had helped stabilize labor relations in the garment industry and would later serve as general counsel to the Port of New York Authority. During the 1880s and 1890s Marshall had probably argued more cases before the Court of Appeals than any other lawyer. Not to be outdone, the Lockwood Committee put together an extremely well-qualified team of lawyers, which included Cohen, Elmer G. Sammis, and Bernard Hershkopf, a member of Guthrie, Bangs & Van Sinderen, one of New York's foremost law firms. At the request of Governor Alfred E. Smith, Charles D. Newton came on board. And at the urging of Hershkopf, William D. Guthrie, the senior partner in Guthrie, Bangs & Van Sinderen, agreed to defend the emergency rent laws in the appellate courts. As towering a figure as Marshall, Guthrie was a highly successful corporate lawyer who had probably appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court as often as anyone. He was also a leading authority on the Fourteenth Amendment, which he had long viewed as the principal safeguard against misguided social legislation. By defending the emergency rent laws, writes one legal scholar, Guthrie would be arguing against “the sanctity of private property which he had done so much to preserve.” Guthrie's decision, which astonished many of his fellow lawyers, was a great boon for the defense. With such an eminent conservative jurist on our side, “we could not be called a bunch of radicals,” wrote Cohen.6

What the Times called preliminary skirmishes got under way soon after the September laws went into effect. Most of them took place in the New York Supreme Court, which, its name notwithstanding, was a trial court as well as an intermediate appellate court. According to the Times, the first case to be “decided squarely” on constitutional grounds was brought in early October by Jacob L. Guttag, the owner of an apartment house on Crotona Parkway who asked the court to eject Hyman Shatzkin, a tenant who had balked at signing a new lease at a much higher rent and refused to move out when the old lease expired. In a Bronx courtroom that was jammed with landlords, tenants, and lawyers, Guttag's counsel, Bernard S. Deutsch, asked Judge Edward R. Finch, a former state assemblyman, to oust Shatzkin, arguing that the legislature had overstepped its constitutional limits by suspending ejectment. Claiming that the “emergency” was a “bug-a-boo” created by the press, he stressed that if the legislature was allowed to suspend ejectment for two years it might as easily suspend it indefinitely. Shatzkin's lawyer, Julius D. Tobias, countered that the legislature had the power to determine that an emergency existed and to deal with it. Chapter 947 did not strip the New York Supreme Court of its power to eject tenants; it just limited it “for a certain time.” Two weeks later Finch ruled in favor of Shatzkin. The September laws were constitutional, he wrote. It was up to the legislature, not the courts, to determine whether an emergency existed. And in his judgment the means adopted to deal with it were “appropriate to the end sought.” Praised by Hilly, who called it “as fine a piece of judicial interpretation as I have seen in many a day,” and the Times, which voiced the hope that it would stand up on appeal, Finch's decision was a “decisive blow” to the landlords, wrote the Bronx Home News.7

The blow was cushioned somewhat at the end of October, when Judge Henry D. Hotchkiss, a Tammany Hall chief and close associate of former Tammany leader Richard Croker, granted a motion by Rose Heyman, the trustee of an apartment house on West 104th Street, asking the court to eject a holdover tenant by the name of Louis W. Osterweis. In explaining his decision, Hotchkiss made the point that chapter 947 applied only to leases entered into after September 27, 1920, the day on which the September laws went into effect, which was not so in the case at hand. If construed otherwise, it would be unconstitutional. Hotchkiss could have stopped at this point. But instead he went on to say that the constitutionality of the September laws “should be passed upon by the court of last resort as soon as possible.” And though he found it “impossible” to express his views on the issue in “a formal opinion,” he had no compunction about declaring that he had “grave doubts” about the validity of chapter 947. In conjunction with chapter 942, it deprived landlords “of all remedy for the repossession of their property.” Since the act did not compensate them for any losses, it could not be upheld as a proper use of eminent domain; nor could it be sustained as “a valid exercise of the police power.” Chapter 947 also discriminated between owners of old buildings and owners of new buildings as well as between “owners who seek to regain possession of their property for their personal use and those who seek possession for other purposes.”8 In other words, it deprived landlords of property without providing them the due process of law and denied them the equal protection of the law.

If the real estate interests’ hopes were raised by Judge Hotchkiss, they were dashed by Judge Robert F. Wagner, a Democrat who had spent over a decade in the New York State legislature and would later serve four terms in the U.S. Senate. A month after Hotchkiss sided with the landlord in Heyman v. Osterweis, Wagner ruled for the tenant in two cases, Levy Leasing Co., Inc. v. Siegel and Ullmann Realty Co. v. Tamur. The first case went back to the spring of 1920, when Levy Leasing, which owned an apartment house on West 57th Street, notified Jerome Siegel that the two-year lease on his apartment, the rent for which was $1,450 a year, was going to expire on October 1. Unless he signed a new lease, under which the rent would be raised to $2,160 a year, he would have to vacate the premises. Afraid that he would be unable to find another apartment, Siegel signed the lease in May, agreeing to pay $180 a month starting on October 1. But when the first month's rent came due, Siegel informed Levy Leasing that he was willing to pay the old rent, but not the new rent. Levy Leasing filed suit, asking Wagner to grant a motion ordering Siegel to pay the outstanding $180. In his defense, Siegel claimed not only that he had had signed the lease under duress, but also that he was protected by chapter 944, which prohibited landlords from charging an unreasonable rent. In response, Levy Leasing argued that chapter 944 was unconstitutional. Wagner held otherwise and denied the company's motion.9

In the second case Wagner did more than just rule in favor of a tenant named Kintara Tamur, who had held over in her apartment on East 66th Street after Ullmann Realty raised the rent from $30—which, observed the judge, she “has ever since been ready and willing to pay”—to $35. He also dealt with an issue that Judge George V. Mullan had sidestepped a few weeks earlier on the grounds that the trial courts should leave constitutional issues up to the appellate courts. That issue was the constitutionality of chapters 942, 944, and 947, the centerpiece of the rent laws. After a trial at which Guthrie and Cohen appeared as amici curiae, Wagner held that the rent laws did not impair contractual obligations. Nor did they deprive landlords of property without due process of law. Dismissing the plaintiff's argument that the statutes applied to dwellings, but not to hotels and rooming houses, and to large cities, but not to small ones, Wagner said the statutes did not deny landlords the equal protection of the law either: “The Constitution only requires that those similarly situated shall be treated alike, not that all shall be subject to the same regulations.” Summing up his sweeping decision, Wagner wrote, “I cannot subscribe to any doctrine that hinders or restrains our legislative power from enacting a clear and reasonable design to relieve the actual distress of the thousands of tenants in this community who would otherwise be made homeless. I think their rights to homes in which to live during an emergency of the kind which now confronts us is transcendentally paramount to any private rights of property.”10

Julius H. Zieser, a spokesman for the Real Estate Investors, Inc., downplayed the significance of Ullmann v. Tamur, saying that it was only the opinion of “a court of first instance” in “a highly technical legal skirmish.” But as the World wrote soon after the decision was handed down, there was no denying that thus far the real estate men had failed to show that the legislature had overstepped its constitutional bounds. If things looked bleak for the landlords in late November, they looked even bleaker in early December, when Judge Leonard A. Giegerich, a Tammany stalwart who was serving his third fourteen-year term on the bench, upheld the constitutionality of chapter 942 in two virtually identical cases. In neither case were the facts in dispute. The plaintiffs, the Brixton Operating Corporation and the Durham Realty Corporation, each of which owned a large apartment house on the Upper West Side, had asked Judge Edward B. La Fetra to issue a precept, which was the first step in bringing summary proceedings against a holdover tenant. When La Fetra denied the request on the grounds that chapter 942 barred landlords from bringing summary proceedings except under circumstances that did not apply in the cases at hand, the plaintiffs asked Giegerich to grant a writ of mandamus compelling La Fetra to issue the precept on the grounds that chapter 942 was unconstitutional. Following a hearing in early November, Giegerich denied the plaintiffs’ motions—and not on the narrow grounds that summary proceedings was a statutory remedy that once given could be taken away, but rather on the broad grounds that chapter 942 was a valid exercise of the police power.11

Judge Giegerich's decisions were a crushing blow to New York's real estate men, one of whom denounced them as the triumph of “sentiment” over “logic.” For Brixton and Durham were more than legal skirmishes. They were full-scale test cases that had been brought by the Real Estate Board, of which at least one of the plaintiffs was a member. Well aware of their significance, both sides sought the help of several of New York's most eminent lawyers. Chief among them were Ingraham, who was retained by the Real Estate Board, and Cohen and Guthrie, who, with Sammis and Hershkopf, filed a brief of more than one hundred pages on behalf of the attorney general and the Lockwood Committee. Of all the lawyers, none made a longer or more impassioned argument than Ingraham. In his fifty years at the bar, some of which had been spent in the very court in which he now appeared, he had never seen such an attempt “to absolutely despoil an owner of his property.” The emergency rent laws—by which “the legislature can take away a man's property, devote it not to a public use, but to a private use, without paying him a particle of compensation for it”—were not just a violation of the federal and state constitutions. They were “the entering wedge” in the effort to “subvert the government.” When his turn came, Guthrie argued that the emergency rent laws were well within the state's police power. And after claiming that Brixton and Durham were perhaps “the most important case[s] that [have] ever come before this court,” Cohen said, “I cannot picture the disorder, the misery, the tumult that will result if the court decides against the constitutionality of this law.”12

Even before Judge Giegerich issued his rulings in Brixton and Durham, it was clear that the real estate interests intended to appeal one or more of the trial court decisions. But down through late December it was far from clear how the Appellate Division would rule. The Second Department had recently heard a case about the constitutionality of the rent laws, but its decision was inconclusive. The case was brought by the Rayland Realty Company, a Brooklyn firm that had asked New York Supreme Court Judge Leander B. Faber to issue a writ of mandamus compelling William R. Fagan, a municipal court clerk, to sign an eviction warrant against a holdover tenant. When Faber refused, Rayland Realty appealed. After a trial in which the main issue was the constitutionality of chapter 942—about which Ingraham, Scott, Guthrie, and I. Maurice Wormser, the editor of the New York Law Journal, all submitted briefs—the court ruled for the defendant, who was represented by Assistant Corporation Counsel William B. Carswell. Writing for the majority, Justice Almet F. Jenks rejected the plaintiff's argument that chapter 942 prevented landlords from regaining possession of their property. “The statutory remedy [summary proceedings] is not abolished,” he wrote; “it is but postponed and for a definite period.” He also dismissed the plaintiff's argument that chapter 942 deprived the landlord of property without due process of law. “The statute does not touch the title of the owner.” Nor does it take the premises. All it does is “interfere to a degree for two years with the owner's absolute control.” In light of the current emergency, “I cannot see that the statute flouts the Constitution.”13

To most of the other judges, the issue was less clear-cut. Of the three who concurred in Jenks's decision, two wrote separate opinions—and one of these held that while chapter 942 was constitutional, there were “very grave questions” as to the constitutionality of chapters 944 and 947. To complicate matters, Abel E. Blackmar, a Republican who had been elected to the New York Supreme Court in 1908 and appointed to the Appellate Division nine years later, disagreed with his colleagues. In a forceful dissent, he argued that chapter 942 deprived the plaintiff of his property “for upwards of two years.” And it did so without due process of law. There was no doubt that the state could regulate the use of property, even “to the injury of the owner,” Blackmar conceded. But the means employed had to have a “real substantial relation” to the ends sought. Since chapter 942 would not “add one square foot” to the housing stock, it was hard to see how it would ease the housing shortage. In the case at hand the property was not taken “for a public use,” he pointed out; nor was the owner compensated for his loss. By taking private property and devoting it to private use, the legislature had stepped over the boundary of the police power. Blackmar conceded that the state might be justified in exercising its police power where it involved a “comparatively insignificant taking of private property for what in its immediate purpose is a private use.” But given that chapter 942 prevented the plaintiff from recovering his property for two years, during which time he had to pay the bills as they came due but could not raise the rents as he saw fit, this was hardly a “comparatively insignificant taking.”14

Two and a half weeks later, one day before Christmas, the First Department of the Appellate Division issued several eagerly awaited rulings on the constitutionality of the emergency rent laws. Once again the results were inconclusive, indeed so inconclusive that it was now certain that the issue would have to be settled by the Court of Appeals. The First Department, it turned out, was as sharply divided as the Second Department. Among the more than half a dozen cases considered by the First Department was Guttag v. Shatzkin, in which the plaintiff asked the court to reverse Judge Finch's decision upholding chapter 947 and grant its motion to eject the defendant from his apartment. Well aware of the importance of the case, both sides assembled a large team of eminent lawyers. Joining Deutsch, Guttag's lawyer in the trial court, were Wormser, Zieser, and Scott, counsel to the Real Estate Interests, Inc. Appearing as amici curiae on behalf of the Real Estate Board were McNulty, Ingraham, and John M. Stoddard, an associate governor of the board and a partner at Stoddard & Mark, the firm that had represented the Brixton and Durham companies before Judge Giegerich. Representing Shatzkin were Tobias and Gilbert Ray Hawes, a well-known real estate lawyer. Appearing for the state were Cohen and Guthrie. Also on hand were Sammis and Hershkopf, counsel for the Lockwood Committee, and Joseph A. Seidman, counsel for the Marcus Brown Holding Company, which was challenging the constitutionality of the rent laws in federal court.15

The case against the emergency rent laws was spelled out in a long brief submitted by Deutsch, with Scott, Wormser, and Zieser of counsel, and a short one submitted by McNulty, with Ingraham and Stoddard of counsel. Declaring that “no clearer case has ever been presented of legislation absolutely in conflict with the fundamental law of this State and of the United States,” Deutsch argued that chapter 947 violated article 6, section 1 of the state constitution by stripping the New York Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over “the common law action of ejectment.” Read in conjunction with chapter 942 and applied to leases entered into before the statute went into effect, it violated article 1, section 10 of the federal constitution too. If this did not impair contractual obligations, “it is difficult to conceive what would.” Chapter 947 also deprived the appellant of property without due process of law, wrote Deutsch. It allows him “to have the satisfaction, forsooth, of calling himself an owner,” but takes away “his power of possession and of repossession, which is at the basis of all private right of property.” And the property in question was private, in no way “a business charged with the public use.” Citing Judge Hotchkiss's decision in Heyman v. Osterweis, Deutsch also argued that chapter 947 violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. After claiming that the statute would do nothing to alleviate the housing shortage, Deutsch concluded that chapter 947, along with chapter 942, was “a deliberate and wanton affront to the genius of our ancestors. Such laws would be eminently in place in a communistic form of government,” but not in the United States.16

McNulty made many of the same points as Deutsch. But instead of just challenging the constitutionality of chapter 947, he launched an all-out assault on the emergency rent laws, of which he had long been one of the most outspoken opponents. Under the U.S. and New York State constitutions, he pointed out, an owner was entitled to possession of his property. But under the rent laws, he “cannot institute any proceeding to recover his property. He cannot enforce any agreement for rent of the property, if the tenant alleges that it is unreasonable and oppressive, but if he fails to furnish such occupant with hot and cold water, heat, elevator service, and any other service or facility, and if he interferes with the quiet enjoyment of the lease premises, he is guilty of a crime.” In defense of such blatantly unconstitutional measures, McNulty pointed out, it was argued that the legislature had determined that the state was facing an “emergency.” But the legislature did not define “the emergency,” nor did it spell out how to deal with it. It was also argued that under the rent laws the landlord's property was taken for only two years. But if the legislature can take the property for two years, it can take it “for twenty years.” The courts have long held that the state can regulate grain elevators and other businesses “devoted to public use” and “in which the public have an interest,” McNulty acknowledged. But they had never said “that it can take the property of a private person and compel him to devote it to [a particular] service, and then regulate the charges that he is entitled to receive for the use of his property.”17

The case for the emergency rent laws was also spelled out in two briefs—one of only ten pages that was drafted by Tobias, with Hawes of counsel, and another of over one hundred pages that was prepared by Guthrie, Cohen, Sammis, and Hershkopf, who submitted it to the appellate court not only in Guttag v. Shatzkin, but in four other closely related cases as well. In his brief Tobias argued that chapter 947 did not “abrogate, limit or suspend the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.” It merely suspended the landlord's right to bring an action in ejectment against a holdover tenant “except under certain conditions, within a limited period of time.” Although the New York Supreme Court is vested with “general jurisdiction in law and equity,” it is well within the power of the legislature to regulate its practices and procedures, Tobias insisted. He also pointed out that New York City was facing “a public emergency,” a consequence of the postwar housing shortage. To deal with it, the legislature was driven to use its police power. It enacted chapter 137 of the April laws, which was designed to deter landlords from bringing summary proceedings in the municipal courts. And when some of them attempted to get around the statute by bringing ejectment actions in the state courts, it passed chapter 947. Like other laws that were based on the police power, chapter 947 did not compensate the property owners for their losses. But such laws are not unconstitutional, Tobias argued, because “they do not appropriate property for public use, but simply regulate its use and enjoyment.”18

In their brief, a revised version of one that was filed with the trial court in Brixton v. La Fetra, Guthrie and his associates, relying heavily on the findings of the Lockwood Committee and the State Reconstruction Commission's Housing Committee, described the emergency that had confronted the legislature in September 1920. Next they discussed what other countries had done to mitigate the impact of the worldwide housing shortage and summarized the rent laws and the recent rulings upholding them. Guthrie and his associates then argued at length that neither the contract clause nor the due process clause “abridges” the power of the legislature to enact “appropriate and necessary laws” to safeguard the public welfare. After reviewing the historical precedents for the emergency rent laws, they went on to stress that the distinctions in the laws between residential and commercial property, large and small cities, and old and new buildings were fully justified and in no way a violation of the equal protection clause. Guthrie and his associates also denied that chapter 947 was invalid on the grounds that it stripped the New York Supreme Court of its jurisdiction over ejectment. They even argued that chapters 942 and 947 were valid if applied in the case of leases entered into before they were enacted, an issue on which the courts were sharply divided. Calling the attack on the September laws “a manifestation of the intolerance with which only too many lawyers approach the novel in legislation,” they concluded that our constitutions “do not stay progress nor forbid innovation, and the powers of government thereunder seeking the accomplishment of legitimate ends are equal to all emergencies.”19

On the basis of the briefs and oral arguments, which were heard in December, the Appellate Division reversed Judge Finch's ruling and granted Guttag's motion, allowing him to oust Shatzkin. In an opinion that was handed down the day before Christmas, Justice Francis C. Laughlin, a New York Supreme Court judge since 1896 and a member of the Appellate Division since 1900, held that chapter 947 was unconstitutional. The statute, which suspended ejectment in the state supreme court for over two years except under exceptional circumstances, was “a clear encroachment upon the jurisdiction of the court,” which is derived “not from the Legislature, but from the [State] Constitution,” and thus a violation of article 6, section 1. The statute was also a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, Laughlin said. In conjunction with chapter 942, it left the landlords with no way to remove a tenant after his lease expired. The legislature had the power “to take away one remedy and substitute another.” But by taking away every remedy—by, in effect, making it impossible to enforce a “lawful contract”—it deprived the owner of property without due process. It was up to the legislature to determine whether an emergency existed, Laughlin conceded, but in attempting to deal with it by enacting chapter 947, the legislature “has not adopted means appropriate to the end.” John Proctor Clarke, who had succeeded Ingraham as presiding justice in 1916, concurred. So did Victor J. Dowling and Samuel Greenbaum. Edgar S. Merrell dissented—though neither he nor the others filed a separate opinion.20

Besides Guttag v. Shatzkin, the First Department of the Appellate Division also heard Brixton and Durham. In both cases, the appellants asked the court to reverse Giegerich's decision upholding chapter 942 and grant a writ of mandamus to force La Fetra to sign the precepts. At issue in each case was the constitutionality of the statute that suspended summary proceedings for just over two years. Both sides relied pretty much on the same group of eminent lawyers who had appeared before Giegerich—among them Ingraham, Stoddard, and McNulty for the appellants and for the respondents Assistant Corporation Counsel John F. O'Brien and Deputy Attorney General Robert P. Beyer as well as Guthrie, Cohen, Sammis, and Hershkopf. Since the facts were more or less the same in both cases, the court decided to deal with the constitutional issue in Brixton and then apply the ruling to Durham.21

On behalf of the Brixton Operating Corporation—and, as the judges of the First Department were well aware, on behalf of the Real Estate Board as well—Ingraham launched an all-out attack on chapter 942. In a brief that ran sixty-eight pages, he argued that the statute violated several provisions of the U.S. and New York State constitutions, chief among them the contract clause, due process clause, and equal protection clause. Under chapter 942, Ingraham pointed out, a tenant can remain in the apartment after the lease expires—even if he has signed a contract to move out and even if other tenants want to move in. And he can remain there as long as he wants, provided only that he pays “what the Court may find as a reasonable rent.” Or if the tenant prefers, he can move out—and, since his lease is no longer binding, he can do so “at any time.” In other words, the tenant “is given the possession of the property without the consent of the owner.” Chapter 942, Ingraham went on, was not for the benefit of the public. It and the other September laws were “solely for the benefit of occupants of apartments who are trespassers, to meet no emergency that now exists, except to prevent owners of property from gaining possession of their property from tenants whose terms have expired.” Hence they are “an appropriation of real property for the benefit of individuals, without due process of law, without compensation, and, so far as appears in this record, without any public interest requiring such drastic legislation.”22

According to Ingraham, the respondent's case was based on the assumption that chapter 942 was a valid exercise of the police power. But this assumption was untenable. It had long been settled that the state could use its police power in ways that infringe on property rights “where a person is engaged in performing a State duty” and “where a person is engaged in performing a duty in which the public has an interest.” But it could not use the police power in matters “in which neither the State nor the public has any interest.” In the case at hand no claim was made that “the State requires this property for public use.” Nor was a claim made that the appellant “has devoted its property to a public use.” It was argued that the state legislature enacted the rent laws because it found that an “emergency exists.” But, responded Ingraham, if the legislature can deprive the appellant of the power to enforce a lawful contract and take away his property and hand it over to someone else just because it believes that an “emergency exists,” the contract and due process clauses of the federal and state constitutions “are mere shams.” It was also argued that the state can only take the appellant's property for two years, but if it can take it for two years, said Ingraham, it can take it for twenty years. No matter how dire the situation, Ingraham argued, the state legislature has no power “to override or violate express constitutional provisions, whether in the exercise of the so-called police power or in the exercise of any other power derived under the State Constitution.”23

Appearing on behalf of Attorney General Newton, Guthrie and Cohen made much the same arguments in defense of chapter 942 that they had made in defense of chapter 947. Beyer, who also appeared on behalf of Newton, and O'Brien, who represented La Fetra, also denied that the statute was unconstitutional. Chapter 942 was “a lawful exercise of the police power,” Beyer insisted. Relying heavily on Judge Finch's decision in Guttag v. Shatzkin, which described at length the emergency that had faced the legislature after World War I, he claimed that the statute was “absolutely necessary” to relieve the “anticipated distress of many thousands of tenants who would [otherwise have been left] homeless.” Neither property rights nor contractual rights are absolute, Beyer pointed out. Both are subservient to the public welfare, which may sometimes justify “the taking, using and even destruction of private property.” In addition to responding to Ingraham's arguments, both Beyer and O'Brien stressed the point that summary proceedings was a statutory remedy. As Beyer wrote, “The law is well settled that where a particular remedy … had its origins solely in statutory enactment … such remedy may be destroyed or restricted at the pleasure of the legislature.” Or as O'Brien put it, what the legislature gave, “it can take away.” It even had the authority to strip the courts of jurisdiction over landlord-tenant disputes. La Fetra “did not refuse to perform his duty to entertain appellant's application [for a precept],” O'Brien concluded. “He did consider it and, acting judicially, denied it.”24

In the end the Appellate Division sided with Beyer and O'Brien, affirming Giegerich's decision and upholding the constitutionality of chapter 942. Writing for a unanimous court, Judge Laughlin held that none of the many authorities cited by Ingraham convinced him and his colleagues that “a party to a contract” was entitled to “the precise remedy” that was available at the time the contract was signed. The rule was that contracts “are deemed to have been made subject to legislation changing the remedy for the enforcement thereof.” A statutory remedy, of which summary proceedings was one, “may be modified or withdrawn” as long as “some adequate remedy remains.” In light of the court's ruling in Guttag v. Shatzkin, which was issued on the same day as Brixton v. La Fetra, such a remedy was available to the plaintiff. In other words, chapter 942 did not deprive the Brixton Operating Company of property without due process of law because it could still regain the premises by bringing an action in ejectment. Summary proceedings, Laughlin acknowledged, was “a more speedy remedy” than ejectment, but the difference was not sufficient reason for the court to hold that its suspension “unlawfully impairs the value of the contract.” In conclusion, wrote Laughlin, “the court would not be warranted in annulling this act of the Legislature merely on the ground that thereby the plaintiff was relegated to an adequate, but less summary and speedy and somewhat more expensive, remedy than was afforded by law when the contract was made.”25

“Rent Day,” by Ryan Walker (New York Call, March 24, 1918, Harvard College Library)

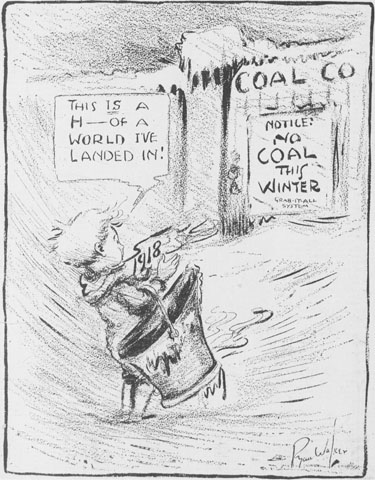

“No Coal This Winter,” by Ryan Walker (New York Call, December 30, 1917, Harvard College Library)

“They Asked [for] Heat and Got This” (New York Call, February 20, 1918, Harvard College Library)

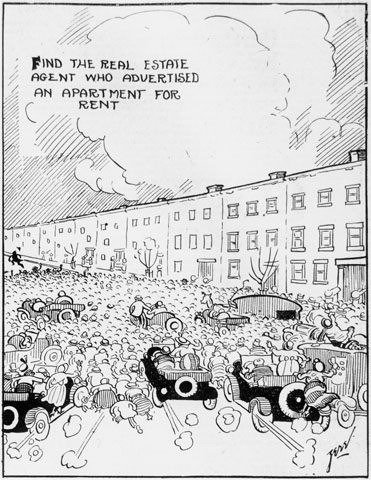

“And This Is No Joke …,” by Zere (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 16, 1919, Harvard College Library)

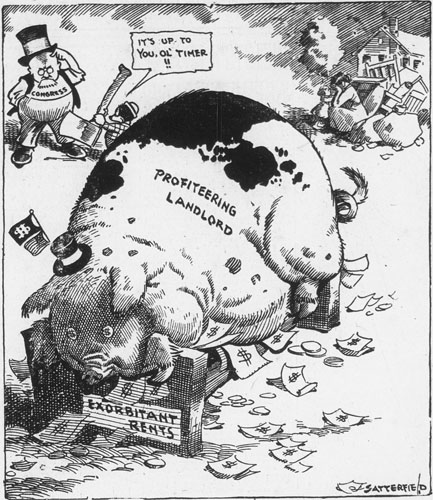

“Wallowing in It,” by Robert W. Satterfield (New York Call, June 24, 1918, Harvard College Library)

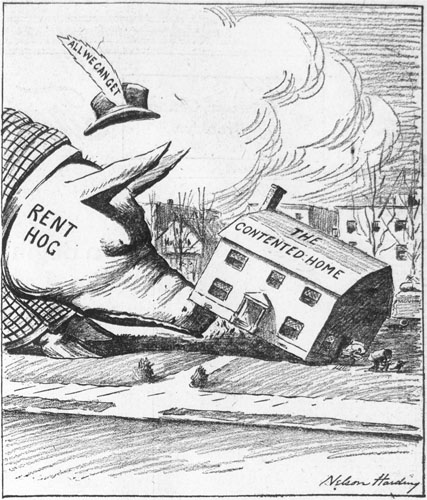

“Rooting It Up,” by Nelson Harding (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 7, 1920, Harvard College Library)

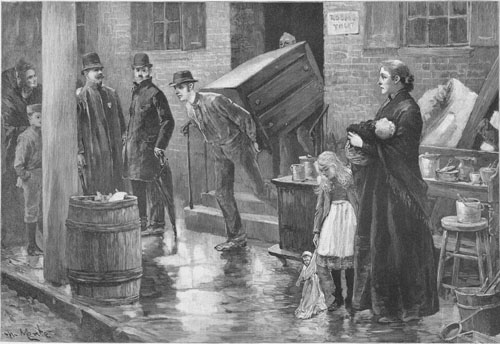

“An Eviction in the Tenement District of the City of New York,” by Charles Mente (Harper's Weekly, February 1, 1890, Harvard College Library)

“An East Side Eviction” (New Era Illustrated Magazine, May 1904, Harvard College Library)

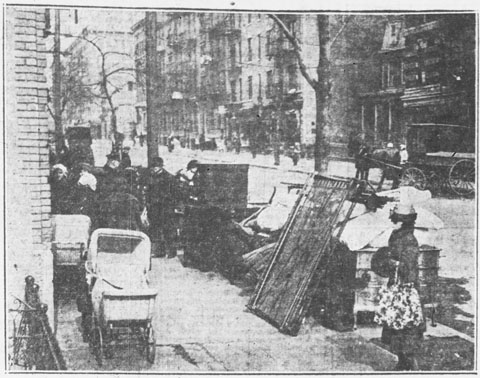

An eviction in New York City (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

“Evicted Brownsville Rent Strikers Make Their Homes in the Streets” (New York Call, May 21, 1918, Harvard College Library)

Striking tenants outside their building (September 1919, Bettmann/CORBIS)

Rent strikers on the street (March 1920, Bettmann/Corbis)

“The Overflow Crowd in the Street at Bronx Municipal Court” (Bronx Home News, October 7, 1919, General Research Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

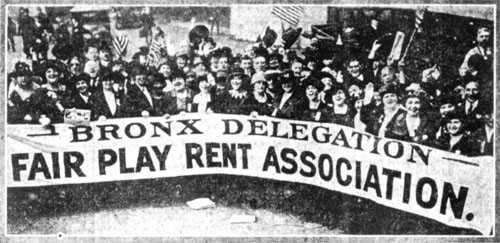

“Patriotic Bronx Citizens Ready to Fight for Their Homes. A Part of the Delegation at the Albany Hearing” (Bronx Home News, January 26, 1920, General Research Division, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

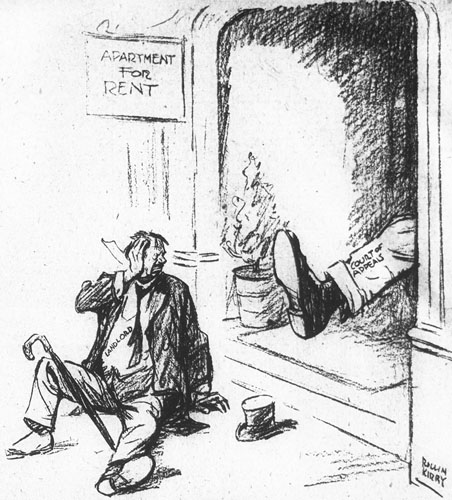

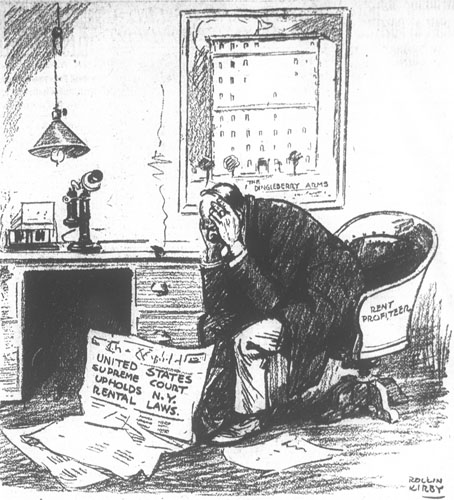

“Another Czar Dethroned,” by Rollin Kirby (New York World, September 25, 1920, Harvard College Library)

“Right in the Nose!” by Nelson Harding (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 27, 1920, Harvard College Library)

“Evicted,” by Rollin Kirby (New York World, March 10, 1921, Harvard College Library)

“Out of Luck,” by Rollin Kirby (New York World, April 20, 1921, Harvard College Library)

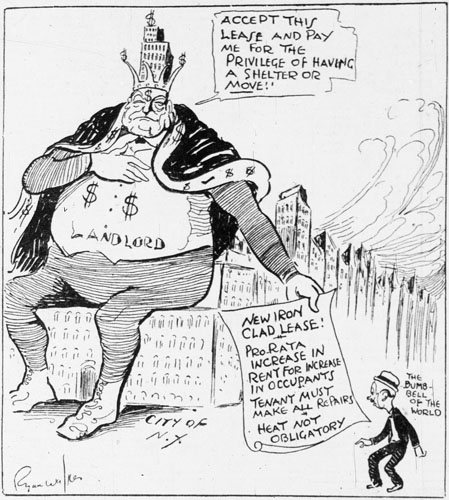

“The New Lease,” by Ryan Walker (New York Call, July 12, 1923, Harvard College Library)

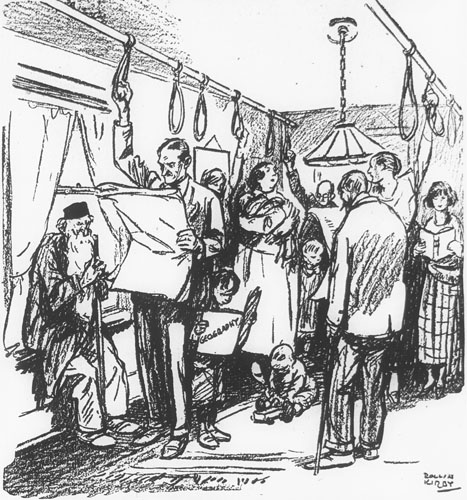

“A New York Apartment if Overcrowding Goes On,” by Rollin Kirby (New York World, October 17, 1923, Harvard College Library)

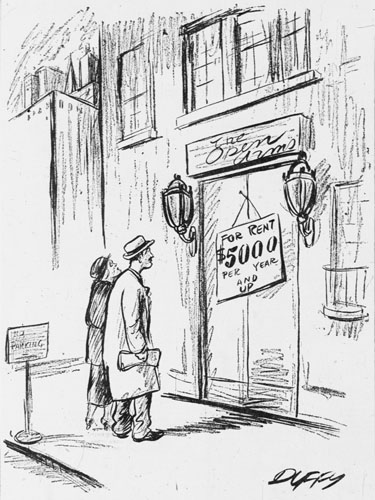

“For Rent: $5000 per Year and Up,” by Edmund Duffy (New York Leader, October 18, 1923, Harvard College Library)

Tenants rally with banners at City Hall (November 9, 1925, Bettmann/CORBIS)

Yet another case that was heard by the First Department of the Appellate Division was Edgar A. Levy Leasing Co., Inc. v. Siegel, in which Wagner had ruled that Siegel was within his rights to refuse to pay the new rent on the grounds that it was unreasonable. At issue was the constitutionality of chapter 944. Representing Siegel was Rose & Paskus, a prominent firm that had been formed in 1878 as Rose & Putzel. Once again Guthrie and Cohen appeared on behalf of the attorney general and Sammis and Hershkopf on behalf of the Lockwood Committee. Representing Levy Leasing was Lewis M. Isaacs, a member of M.S. & I.S. Isaacs, a firm that had been founded in 1862 by his father Myer, who was joined by his brother Isaac five years later. One of New York's most prominent Jewish firms, it specialized in real estate law. Joining Isaacs, with whom he had appeared in 810 West End Avenue, Inc. v. Stern, another case that was heard by the First Department in December, was Louis B. Marshall, who was retained by the Real Estate Board. As the board was well aware, Marshall was not only one of the leading authorities on constitutional law, but also one of the sharpest critics of the police power. As he wrote Isaacs in early October, he strongly objected to the rent laws, of which he regarded chapter 944 as the most egregious. Some of the laws, notably chapter 942 and three others that dealt with summary proceedings, would probably be upheld by the courts, but “read in conjunction with Chapters 944 and 947,” he pointed out, “the entire legislative scheme constitutes a violation of the Constitution.”26

In the brief submitted on behalf of Levy Leasing, Marshall and Isaacs argued that chapter 944 violated both the U.S. and New York State constitutions. Taking issue with the argument that it was a valid exercise of the police power, they pointed out that the plaintiff's property was not devoted to “any public use.” It was not, in the words of the U.S. Supreme Court, “affected with a public interest.” To hold that the legislature had the right to regulate the rent of apartments would be to hold that it had the right to regulate the price of food and clothing. No matter how grave the alleged emergency, a point that was made much of by counsel for the defendant, the legislature cannot disregard “the safeguards contained in our fundamental law.” Even if the housing shortage was as acute as the legislature (and the governor) claimed, which it was not, chapter 944 would do nothing to alleviate it. If anything, the statute would exacerbate the problem.27

Marshall and Isaacs also asked the court to strike down chapter 944 on the grounds that it prescribed no standards by which to determine whether the rent was unreasonable; and such standards, they argued, were necessary to ensure due process of law. Although the statute required the landlord to file a lengthy bill of particulars, it said nothing about how to calculate the value of the property, which was essential in any attempt to figure out a reasonable rent. Nor did it take into account that during the prewar years many landlords had rented their apartments for so little that they had earned “considerably less than the legal rate of interest.” The statute was also silent about the deadbeat tenants and the myriad of other things that landlords consider in setting a rent that would yield a reasonable return. New York City had fifty-two supreme court justices, ten city court justices, and forty-five municipal court justices, Marshall and Isaacs told the court. And each one was likely to have his own standards. Under chapter 944, “the rental value of similar apartments located on ten different pieces of property may thus be determined according to ten different standards, with ten varying results, all dependent upon the length of the chancellor's foot.” (A similar position was taken by Wormser, Zieser, and Scott, counsel for the Real Estate Investors, Inc., who argued that chapter 944 “goes further than any legislation which can be found in the statute books.” It is “impractical in its operation,” “discriminatory in its results,” and “seriously dangerous in its tendencies.” “If it is to be upheld because of an alleged emergency,” they wrote, “constitutional limitations are meaningless and fundamental safeguards become an empty sham.”)28

Although Marshall and Isaacs made a strong case against chapter 944, they failed to persuade the court. Writing for the majority, which included Merrell and Greenbaum, Laughlin ruled that the statute did not violate the due process clause. It was not necessary for the court to decide whether the renting of houses and apartments in big cities was a business “in which the public is so directly or intimately interested as to warrant its regulation in ordinary times,” he wrote. For “that has not been attempted.” What had been attempted was to regulate rents during an emergency. And that was a valid exercise of the police power—and not, as Marshall and Isaacs argued, a violation of the due process clause. The legislature cannot compel the landlords to open their doors to the homeless, Laughlin explained. That would be “a taking of the property.” But during an emergency it may provide that “so long as they see fit to lease their property and enjoy the protection of the state, they must deal justly with their tenants.” The legislature showed “great foresight” in enacting chapter 944, he added. The statute would stop profiteering landlords from taking advantage of the housing shortage and exacting “unreasonable and unconscionable and extortionate rentals for the use of their property.” It would also deter them from evicting hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers who would have been hard-pressed to find other accommodations. Indeed, even if chapters 942 and 947 were held unconstitutional, chapter 944 would do much to prevent the landlords from carrying out “their threats of wholesale evictions.” So long as they could only charge a reasonable rent for their apartments, they would have no incentive to replace one tenant with another.29

Laughlin disposed of Marshall and Isaacs's other points in a succinct, almost perfunctory manner. Contractual obligations were not “absolute and universal,” he wrote. The state has the power to modify them, provided it does so in a way that is designed to promote the general welfare, that is reasonable, and that is not applied retroactively. To Marshall's argument that chapter 944 denied the plaintiff the equal protection of the law, Laughlin responded that it was confined to property that was “devoted to the same use,” that it “embrace[d] all such property,” and that it applied to this property and to no other. To the argument that chapter 944 prescribed no standards by which a reasonable rent was to be determined, he answered that it provided that a landlord was entitled to “a reasonable income on his investment,” which was an adequate standard. Laughlin's decision did not sit well with Clarke, who agreed with Marshall and Isaacs that chapter 944 violated the due process clause and other provisions of the federal and state constitutions. But rather than elaborate on his views, he filed a brief dissent, with which Dowling concurred, signaled his agreement with Judge Blackmar's opinion in People ex rel. Rayland Realty Company v. Fagan, and urged that the constitutional issues raised by the rent laws “be submitted as speedily as possible to the Court of Appeals.”30

There was little doubt that the Appellate Division's rulings would be challenged in the Court of Appeals. Supporters of the emergency rent laws were severely troubled not only by Guttag v. Shatzkin, but also by 810 West End Avenue, Inc. v. Stern, another case in which the court held that chapter 947 was unconstitutional. Under these rulings, said Julius D. Tobias, “any landlord wishing to get rid of a tenant need only to begin ejectment proceedings in the Supreme Court.” Since the tenant was left with no defense, he would be forced to move out in thirty days. Like Judge Harry Robitzek, who believed that as a result of Guttag v. Shatzkin practically all landlord-tenant cases would be transferred to the New York Supreme Court, Tobias predicted that the state courts would soon be as busy as the municipal courts. Opponents of the emergency rent laws were just as troubled by Brixton v. La Fetra, Durham v. La Fetra, Levy Leasing Co. v. Siegel, and Clemilt Realty Co., Inc. v. Wood, another case in which the court held that chapter 944 was constitutional. Under these rulings the landlord would not be able to bring summary proceedings against a tenant whose lease had expired. Nor would he be able to charge more than what the municipal court judge deemed a reasonable rent. From the start both sides had been prepared to take these cases to the Court of Appeals. Now that they had on hand a stellar group of lawyers, who had already done much of the research and drafted much of the briefs, they saw no reason to change their minds.31

Nor was there much doubt that the Court of Appeals would hear the challenges to the Appellate Division's rulings. The constitutionality of the emergency rent laws was a legal issue with profound social, economic, and political ramifications, an issue important enough to engage several of the country's most eminent lawyers. It was also an issue on which the Appellate Division was sharply divided, if not on the validity of chapter 942, then on the validity of chapter 944 (and, to a lesser degree, chapter 947). And it was an issue in which many important institutions, among them the Real Estate Board, the Real Estate Investors, Inc., the attorney general's office, the corporation counsel's office, and the Lockwood Committee, had a deep interest. Hence it came as no surprise that the Court of Appeals agreed to hear six cases that dealt with the constitutionality of the emergency rent laws. (It also agreed to hear three other cases, all of which hinged on whether a municipal court judge could refuse to sign an eviction warrant after a final order was granted, an issue on which the First and Second departments of the Appellate Division were sharply divided.) In mid-January, less than four weeks after the Appellate Division handed down its decisions, what the Times called “a big array of legal talent,” which included Guthrie, Cohen, Marshall, Ingraham, and Scott, made the short trip to Albany and walked into the Court of Appeals Hall, a Greek Revival building not far from the capitol that had housed the high court since the 1910s. There they argued about the constitutionality of the emergency rent laws for three days.32

There was, however, a great deal of uncertainty—and more than a little wishful thinking—about how the Court of Appeals would rule. According to William P. Rae, a prominent real estate man who was leading an effort to persuade the state legislature to repeal or modify the emergency rent laws, the Brooklyn Real Estate Board believed that the court would hold the laws unconstitutional. Writing more than two decades later, Julius Henry Cohen recalled that he and Bernard Hershkopf had been confident that the Court of Appeals would be persuaded by their arguments—though Cohen also remembered that the great majority of Wall Street lawyers expected the court to strike down the emergency rent laws.33 Although some of these people were better informed than others, it is safe to say that none knew how the Court of Appeals would rule. It is also safe to say that none even knew whether the justices would deal separately with each of the statutes, as the Appellate Division judges had, or whether they would issue a decision about the entire legislative package.

If the emergency rent laws had been enacted before World War I, they would have stood little chance in the Court of Appeals. As one legal scholar has written, the prewar court “was widely regarded as hostile to social and economic reform.” If not as “reactionary” as some critics charged, it was highly conservative. It is true that in People v. Lochner, which was handed down in 1904, the Court of Appeals upheld a statute that barred bakeries from requiring employees to work more than ten hours a day and sixty hours a week, a decision that was reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court. But as another legal scholar has pointed out, Lochner was “an exception to the rule.” More typical were People v. Marcus and People v. Williams. In Marcus, which was decided in 1906, the court struck down a statute that outlawed the “yellow dog” contract, which prevented employees from joining labor unions. And in Williams, which was handed down a year later, the court overturned a statute that barred women and children under eighteen from working in factories before six in the morning and after nine in the evening. By far the best known of the court's rulings was Ives v. South Buffalo Railway Co., which was handed down in 1911. In this case the court reversed the Fourth Department of the Appellate Division and held that New York's pioneering workmen's compensation law was not a valid exercise of the police power. The Ives decision generated a nationwide protest, in the vanguard of which were former president Theodore Roosevelt and a group of eminent lawyers that included Roscoe Pound and Ernst Freund.34

Not long after the Ives decision, most of the judges left the court. Between 1912 and 1920 Chief Justice Edward A. Cullen, his successor, Willard Bartlett, and four associate justices stepped down when they turned seventy, the mandatory retirement age for New York State judges. And William E. Werner, who wrote the Ives decision (and staunchly defended it when he ran for chief justice two years later), died in 1916. Of the two judges who were still on the court in early 1921, one was Emory A. Chase, who strongly believed in freedom of contract, but did not take part in the rent laws cases. The other was Frank H. Hiscock, chief justice from 1917 to 1926. Hiscock, who did not take part in the Ives case, was one of the least conservative members of the prewar court. Replacing Cullen, Werner, and their colleagues was a group of well-known figures, some of whom—including Nathan L. Miller, the future governor, and Abram I. Elkus, the chairman of the State Reconstruction Commission—resigned before 1921. Of the judges who remained on the court, the most prominent was Benjamin N. Cardozo, a brilliant lawyer who had been appointed to the Court of Appeals in 1914 and elected chief justice in 1926, a position he held until he was elevated to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1932. Also extremely prominent was Cuthbert W. Pound, who joined the Court of Appeals in 1915 and succeeded Cardozo as chief justice in 1932. Besides Hiscock, Cardozo, and Pound, the other judges who heard the cases about the rent laws were John W. Hogan, William S. Andrews, Frederick E. Crane, and Chester B. McLaughlin, who had been appointed to the Court of Appeals by Governor Charles S. Whitman in 1917.35

The new judges were much more disposed than their predecessors to approach statutes enacted under the police power with what Hiscock called “the presumption of constitutionality.” As a Supreme Court judge in upstate New York, Pound had held that the workmen's compensation law of 1910, the law that was struck down by the Court of Appeals in Ives, was “within the constitutional powers of the Legislature.” And though Cardozo “looked carefully at the particulars of regulation,” writes his biographer, “his sympathy on the big issues was with the power of the legislature to regulate business.” As early as 1915, seven years after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down Muller v. Oregon, which upheld an Oregon law that barred women from working more than ten hours a day, the Court of Appeals, without explicitly reversing People v. Williams, ruled in favor of a statute that barred women from working in factories before six in the morning and after ten in the evening. A few months later, less than two years after the voters adopted a constitutional amendment that was designed in large part to undo Ives, the court held that the state's new workmen's compensation law was constitutional. By the end of the decade, writes Cardozo's biographer, the Court of Appeals was no longer as torn as it had once been “between upholding individual freedom of contract and permitting legislative regulation in the name of safety, health, and protection of the public welfare.” But whether it was ready to go so far as to hold that the rent laws were a valid exercise of the police power remained to be seen.36

Along with assorted notices, affidavits, and the like, the lawyers filed with the Court of Appeals several briefs, the longest and most thorough of which were submitted by Stoddard & Mark, with Ingraham and Stoddard of counsel, by Marshall and Isaacs, and by Guthrie, Cohen, Sammis, and Hershkopf. Aside from taking into account the recent decision in Guttag v. Shatzkin, these briefs covered much the same ground as the ones filed with the Appellate Division (and, in some cases, with the trial courts). Both sides agreed about one thing: rather than deal separately with each of the statutes, the court should treat them as parts of a single legislative package. As both Ingraham and Marshall pointed out, the emergency rent laws were passed at the same session of the legislature. They also dealt with the same subject. This argument was risky. If the Court of Appeals upheld the entire legislative package, it would have to reverse the Appellate Division's ruling in Guttag v. Shatzkin. But Ingraham and Marshall were prepared to take the risk. So were Cohen and Guthrie. Although they were aware that if the court held one of the laws void, it might—indeed, Ingraham argued, it should—hold all of them void, their brief dealt not only with chapter 942, the statute in question in Brixton and Durham, but also with chapters 944, 945, and 947, the three other statutes “of paramount importance.”37

About everything else, however, the two sides strongly disagreed. These disagreements raised a host of difficult questions with which the justices wrestled after the lawyers made their oral arguments in mid-January. Aside from whether chapter 942 violated article 3, section 15 of the state constitution, a technicality to which the court paid no heed, these questions were of great moment. Were the emergency rent laws a violation of the U.S. and New York State constitutions, an argument made by Ingraham, Marshall, and Leonard Klaber, a New York lawyer who submitted a brief as amicus curiae on behalf of the Battery Realty Company? Did they deprive the landlords of property without due process of law, deny them the equal protection of the law, impair contractual obligations, and take private property for public use without compensation? Or were the emergency rent laws a valid exercise of the police power, an argument made by Guthrie and Cohen as well as by Deputy Attorney General Beyer and Assistant Corporation Counsel O'Brien? In the interest of safeguarding “the public health, peace, order and welfare,” in Guthrie and Cohen's words, was the legislature justified in taking what were admittedly unprecedented measures to curb “widespread extortion and oppression in rents” and prevent “wholesale evictions of tenants who were able and willing to pay fair and reasonable rentals for their homes and were unable to find other accommodations?”38

How the justices answered these questions depended in large part on how they answered several other no less difficult questions. The state legislature had declared that New York was facing a public emergency. But was it? Citing the reports of the Reconstruction Commission's Housing Committee, the findings of the Lockwood Committee, and the governor's message to the legislature, Guthrie and Cohen argued that the legislative declaration was “abundantly supported by the facts.” Indeed, they went on, “perhaps no legislation was ever passed by the Legislature of the State of New York which was the subject of more thorough and exhaustive investigation.” Marshall and Isaacs disagreed. Nothing Guthrie and Cohen cited showed that New York's landlords were charging excessive rents, much less earning “an exorbitant profit.” Despite the widespread belief that the city was short 100,000 homes, “nobody has been compelled to live in the street,” and “everyone seems to have a roof over his head.” Based on the reports of the Tenement House Department—and a study made for the Law Committee of the Real Estate Board by Columbia professor Samuel McCune Lindsay—Marshall and Isaacs argued that the supply of housing had kept up with the demand. Citing vital statistics that showed that New York City's death rate was lower in 1919 than in 1918, and even lower in 1920, they denied that the alleged housing shortage was a threat to public health. As for the fear that hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers were about to be evicted from their homes, they contended that there were fewer summary proceedings in 1919 and 1920 than in 1917 and 1918.39

Even if New York was facing an emergency, were the September laws well designed to deal with it? To put it another way, were the means adopted appropriate to the ends sought? Citing the report of the Reconstruction Commission's Housing Committee, Ingraham argued that the problem was not the rent hikes, but the housing shortage. And the way to solve this problem was not to prevent landlords from raising rents, but to encourage builders to erect houses. This the emergency rent laws did not do. Marshall made much the same point. Residential construction was down because it was not profitable, he argued. Labor and materials were very expensive, and capital, “if it can be obtained at all,” was only available at prohibitive interest rates. Since the rent laws would not make residential construction less costly for builders and more attractive to investors, they would do nothing to ease the housing shortage. Guthrie and Cohen disagreed. The housing shortage was a long-term problem, one that even the Real Estate Board, an outspoken opponent of the emergency rent laws, acknowledged could not be solved in the next year or two. In the meantime, something had to be done about the dire consequences of what the Mayor's Housing Conference Committee called a “famine of housing space,” among the most serious of which were the increased overcrowding, the deteriorating sanitary conditions, the soaring rents—which drove even the well-to-do out of their apartments—and the imminent eviction of hundreds of thousands of tenants. It was to alleviate these conditions, not to ease the housing shortage, that the legislature enacted the September laws, Guthrie and Cohen argued.40

Even if the September laws were well designed to deal with the emergency, were they permissible under the U.S. and New York State constitutions? In other words, did the police power extend to dwellings? Given that neither property rights nor contractual obligations were absolute, as Guthrie and Cohen argued, was renting space in apartment houses akin to renting space in grain elevators, whose rates were subject to regulation under the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decision in Munn v. Illinois? Rejecting what one legal scholar calls “a closed concept of businesses affected with the public interest,” Guthrie and Cohen insisted that all property was subject to the police power—and to the state's duty to safeguard, “by fair and appropriate means,” the general welfare of the community. But as Marshall and Ingraham pointed out, a dwelling was not a grain elevator—or, for that matter, a fire insurance company, whose rates were subject to regulation under the high court's ruling in German Alliance Insurance Company v. Lewis. It was in no way devoted to public use. Indeed, it was “the most private” of places, a place in which the public had no interest, a place into which no one could even enter without permission. If the Court of Appeals upheld the emergency rent laws, said Marshall, “there is not a business conceivable, no matter how private it may be, that could not with equal right be made dependent upon the action of the Legislature.” Ingraham was even blunter. At issue before the court, he declared, was whether the Constitution is still “the supreme law of the land” or whether it is to be “relegated to a subordinate position—subordinate to the so-called police power.”41

Among the other difficult questions, a few stand out. The emergency rent laws drew distinctions between residential and commercial property, old and new buildings, and large and small cities. Were these distinctions arbitrary, as Marshall and Isaacs said, and thus a violation of the equal protection clause? Or were they reasonable, as Guthrie and Cohen said? “The Constitution only requires that those similarly situated shall be treated alike,” they argued, “not that all shall be subjected to the same regulations.” How could chapter 944 be constitutional if it did not prescribe standards by which to determine a reasonable rent, Marshall and Isaacs asked? Courts are routinely called on to determine “what is reasonable,” Guthrie and Cohen responded. “The common law prescribes no standards in those cases except the judgment of the ordinary prudent man upon all the relevant facts.” Also, should the court go along with Ingraham and Stoddard, who argued that the Appellate Division was wrong in sustaining chapter 942 on the grounds that it had overturned chapter 947? After all, they pointed out, both statutes were “designed to accomplish the same purpose.” An action in ejectment, the only remedy left to the landlords under Guttag v. Shatzkin, was so slow and costly that it amounted to “a denial of justice.” Or should the court side with Guthrie and Cohen, who urged the justices to reverse Guttag v. Shatzkin on the grounds that under chapter 947 an action for ejectment was still available to the landlords “in every case in which the public interest does not require it to be temporarily suspended?” To affirm the Appellate Division's decision in Guttag would be to say that “no exercise of legislative power,” no matter how sorely needed, was permissible without a constitutional amendment if it in any way suspended or abolished an existing remedy, “no matter how obnoxious to the public interest that remedy may have become.”42

The Court of Appeals issued its decisions on March 8, 1921, roughly ten weeks after the Appellate Division delivered its rulings and seven weeks after the lawyers made their oral arguments. The court agreed with Ingraham and Marshall that the emergency rent laws should be treated as a single legislative package. But on the other issues it sided with Guthrie and Cohen. With only one dissenting opinion, which was written by McLaughlin, the court affirmed the Appellate Division's ruling in People ex rel. Durham Realty Corporation v. La Fetra and People ex rel. Brixton Operating Corporation v. La Fetra. In an opinion written by Pound (and concurred in by Hiscock, Hogan, Cardozo, Andrews, and, with some reservations, Crane), the court held that the emergency rent laws were a valid exercise of the police power. On the basis of the Durham opinion, it also affirmed the Appellate Division's rulings in Edgar A. Levy Leasing Co., Inc. v. Siegel and Clemilt Realty Company, Inc. v. Wood and reversed its rulings in Guttag v. Shatzkin and 810 West End Avenue, Inc. v. Stern. The result was a clean sweep for the emergency rent laws. And writes one legal historian, the Durham opinion convinced Felix Frankfurter, Rexford Tugwell, and other observers that Pound was “a remarkable jurist whose reputation was obscured only by the presence on the Court of his more illustrious colleague Benjamin Cardozo.”43

Pound began his opinion by summarizing the facts at hand and the laws in question. He then pointed out, “If chapter 942 alone were to be considered, we would not hesitate to say that the Legislature may repeal or suspend in whole or in part the remedy of summary proceedings,” which was the main point of Deputy Attorney General Beyer's brief. The landlord has “no vested or contractual property right” in any particular remedy, much less one that was established by statute. But chapter 942 was an integral part of a legislative package that included chapters 944 and 947, wrote Pound. If construed together, they raised serious constitutional issues, at the core of which were two fundamental and long-established principles. One was that “private business may not be regulated, and may not be converted into public business by legislative fiat.” The other was that the state may exercise its police power to impose regulations that are “reasonably necessary to secure the general welfare of the community,” even if “the rights of private property are thereby curtailed and freedom of contract is abridged.” In the cases at hand these principles were in conflict. To resolve the conflict, Pound said, the court had to answer a question that arose out of chapter 944. “May the legislative power, in a season of exigency, consistently with the due process clauses of the state and federal Constitutions designed to protect property rights, so invade the domain of private contract as to interfere with and regulate the right of a landlord to exact what he will for his own in the way of rent for private property?”44

A landlord, Pound pointed out, is a businessman, “a purveyor of a commodity,” the “vender of space in which to shelter one's self and family,” who has “heretofore been permitted to make his own terms with his tenants.” As such he has property rights that cannot be infringed on under ordinary circumstances, among them to pick to whom to rent his space and to charge what he sees fit for it. But circumstances were far from ordinary. As a result there was a disparity between theory and practice. In theory, Pound went on, housing is not a monopoly. Nor is it a public utility, like, say, a railroad. If a tenant cannot find an apartment in one building, he can find one in another. The rent is fixed by “economic rules,” and “the market value is the reasonable value.” People move from one city to another when it suits them. And no one is compelled to live in New York. Thus “to call the legislation an exercise of the police power, when it is plainly a taking of private property for private use without compensation, is a mere transfer of labels, which does not affect the nature of the legislation.” But the theory was at odds with the facts, Pound pointed out. As the legislature found, “the state of demand and supply is at present abnormal,” no one builds because it is not profitable to do so, and the owners of property “seek the uttermost farthing from those who choose to live in New York and pay for the privilege rather than go elsewhere.” The result is that profiteering and oppression have become widespread. “It is with this condition, and not with economic theory,” Pound declared, “that the state has to deal in the existing emergency.”45

To deal with this condition, the legislature turned to the police power, which Pound described as “a dynamic agency, vague and undefined in its scope, which takes private property or limits its use when great public needs require, uncontrolled by the constitutional requirements of due process.” Whether a statute was a valid exercise of the police power depended not on whether a business was devoted to the public use, but rather on whether the use of the property affected the well-being of the community. To construe the police power otherwise, Pound wrote, would be to deprive the state of “one of the attributes for which governments are founded” and leave it “powerless to secure to its citizens the blessings of freedom and to promote the general welfare.” The scope of regulation was constantly widening, he pointed out. And since no similar legislation has come before the courts, “precedent is of little value and may prove misleading.” Nor was novelty an argument against constitutionality, Pound wrote. Citing the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in German Alliance Insurance Company v. Lewis, he stressed that “changing economic conditions, temporary or permanent, may make necessary or beneficial the right of public regulation.” Whether such regulation well serves the public interest or whether it is nothing more than “another example of misdirected zeal in dealing with a crisis”—or even, for that matter, whether a public emergency existed—is not for the courts to say. When reviewed in light of these principles, Pound concluded, the argument that chapter 944 deprives the landlords of property without due process of law is untenable.46

Pound spent much less effort dispatching the other objections to the emergency rent laws. Under these laws, he conceded, “one class of landlords is selected for regulation because one class conspicuously offends; one class of tenants has protection because all who seek homes cannot be provided with places to eat and sleep.” And tenants who are willing to pay exorbitant rents or unable to pay any rent at all “have been left to shift for themselves.” But these distinctions are reasonable, Pound held, and “deny to no one the equal protection of the laws.” Nor did the emergency rent laws violate the contract clause. “The rule alike for state and nation is that private contract rights must yield to the public welfare when the latter is appropriately declared and defined and the two conflict.” Siding with Guthrie and Cohen, Pound also rejected the argument that chapter 944 was unconstitutional on the grounds that it did not prescribe standards by which to determine a reasonable rent. And taking issue with the Appellate Division's ruling against chapter 947, he wrote, “To uphold the right of the landlord to maintain ejectment would be to crack the legislative design into fragments which would afford little protection to the tenants in possession.” In light of present theories of the police power, he concluded, “the state may regulate a business, however honest in itself, if it is or may become an instrument of widespread oppression” and “the business of renting homes in the city of New York is now such an instrument.” It was therefore within the power of the legislature to suspend summary proceedings and actions in ejectment and to prevent landlords from charging more than a reasonable rent.47

McLaughlin disagreed. Eight months earlier he had written the decision in which the Court of Appeals ruled that New York City's pioneering zoning law of 1916 was “a proper exercise of the police power.” But now he believed his colleagues had gone too far. In a long and forceful dissent, which drew heavily on the brief submitted by Marshall and Isaacs, he explained why. Chapter 944 substitutes for the old contract a new one, one that “the parties never made, and to the terms of which they never agreed.” It not only impairs contractual obligations; it destroys them. Under the emergency rent laws, the landlord must permit the tenant to remain on the premises and take whatever rent “the court fixes as reasonable.” Yet the tenant may refuse to pay and move out at any time without giving notice. “If this does not amount to depriving a landlord of his property without due process of law,” McLaughlin wrote, “it is difficult to imagine what would.” By treating the owners of old and new buildings differently, the laws also violated the equal protection clause. “One class is compelled arbitrarily to retain tenants whether desired or not, and to accept what the court fixes as a fair rental, while the other class may select its tenants and fix the rent at an amount upon which the parties agree.” The rent laws also take private property for a private purpose, even though the renting of property is no more a public matter than “the sale of food, clothing, or any other article.” It is much better, McLaughlin concluded, “to adhere strictly to the Constitution, the anchor of good, safe, and sound government, rather than to embark on the sea of paternalism, the dangers of which cannot be foreseen or the perils foretold.”48