8Layers of Life

I am enjoying my life so much more today than in my youth, when I felt isolated and treated as stupid because of my dyslexia. Teamwork and the overlapping layers of work, family and friends have liberated me from this sense of isolation. In the book that accompanied our 2007 exhibition, Richard Rogers + Architects: From the House to the City, Renzo Piano said that I could be ‘a humanist at 9 o’clock in the morning, a builder at 11, a poet just before lunch and a philosopher at dinner time’. If that’s true, then I consider myself lucky.

Ruthie is at the centre of this rich mix of life and work. She is my closest friend and my intellectual partner. We have always worked together – editing books, planning exhibitions, campaigning, getting involved in charitable and community causes – and I count the day a disaster if I don’t speak with her at least six times. People see us walking arm in arm at parties, and think that we are inseparable, which we are, though we have to stay close so that Ruthie can whisper people’s names in my ear. Following the move to Leadenhall, what I miss most is not working alongside her – the spontaneous cups of coffee at the River Café, asking her over to look at a drawing, visiting the kitchen to taste a soup. But we are still on the phone to each other through the day, talking about changes at the practice, staffing at the River Café, the menu, political protests, plans for parties and charity benefits, potential new hires and openings. Our lives are so tightly twined together.

Royal Avenue

When we found our house on the corner of Royal Avenue and St Leonard’s Terrace in Chelsea, it was the view and the light we fell in love with. In one direction was the ‘countryside’ – the grounds of Wren’s Royal Hospital, with the Thames beyond – and in the other the vitality of city life on the King’s Road.

The double-height living space – our internal piazza – at Royal Avenue, with light flooding in from twelve windows and our stainless steel open kitchen under the mezzanine.

The Royal Hospital is an understated English manor house, home for 360 years to army veterans, its yeoman stolidity contrasting sharply with the refined, expressive grandeur of Les Invalides, its Parisian equivalent. Royal Avenue itself was intended to be a grand processional route from the Royal Hospital to Kensington Palace, but it never actually got beyond King’s Road. As ever, London resisted grand plans and I like to imagine the eighteenth-century landowner who put his foot down, bringing the whole project grinding to a halt. Ruthie always says that it is fitting that we live alongside a failed urban project.

The house is south-facing, with light flooding in from three sides. Georgian architecture at its best, from cottages to palaces, is strongly articulated, with proportions that support repetition and extension. The regularity of the façades at Royal Avenue allowed us huge flexibility, as we carved out the interior to create something new. Georgian houses are almost a precursor to modern curtain-walled buildings; rather than windows that define the spaces behind them – a big bay window for the living room or a small window above a sink in the kitchen – the same pattern is repeated. Behind the façade, you can put anything you like.

We moved the main entrance from a formal Georgian front door to an inconspicuous side door on Royal Avenue, leading into an internal courtyard, previously a small north-facing garden, which we glazed over. From here you can see the whole five storeys, from the mezzanine and bedrooms above to the basement below. The top of the stairs is an explosion of space and light; the triple-height main room, the ‘piazza’ as some friends call it, washed with light from twelve traditional full-height sash windows, and the glazed roof over the staircase. After living in the Place des Vosges in Paris, where the main room was large enough for children to ride their bikes, Ruthie wanted the same sense of space in London.

The house is essentially open-minded and social, with bedrooms and bathrooms wrapping round the central space, and guest flats below. A mezzanine – originally designed as a bedroom, but now our study and library – is supported on a T-joint of steel beams painted rich lapis lazuli blue, with high gloss enamel paint usually used for painting helicopter fuselages. Contemporary American paintings hang on the walls; bright-coloured Mexican model animals, and more personal treasures like my mother’s simple stoneware pots grouped in their ‘village’ clusters, are on a low-level shelf beneath them.

There is often a party in the piazza – a friend’s book launch, a charity benefit, an extended-family celebration, our annual celebration of the architect of the Serpentine Pavilion in Hyde Park. Like the River Café, Royal Avenue is a place to gather. On quieter days, there may be grandchildren running around, friends visiting, four different conversations taking place in different languages in different parts of the room. At the centre, as at Creek Vean and Parkside, is a stainless steel kitchen – the focus of our family life, where Ruthie and I sit on high stools to talk at the beginning and end of the day. The house has a rhythm: I can see the sun rising as I begin to work in the peace of early morning, and we can watch it setting from the roof terrace in the evening.

Family and friends at Royal Avenue, celebrating Christmas in 2015.

Our bedroom is at the top of the house. Every morning we wake to the view over the Royal Hospital. The other bedrooms are at the back of the house – Roo’s room still has the Ron Arad chair that he saved up to buy when he was a teenager, and Bo’s collection of model aeroplanes is still on his shelves – with a steel spiral staircase connecting them and the roof terrace, which runs over the whole length of the building. From the terrace – the only place in the house where we cannot hear phones or doorbells – we can see Big Ben, Westminster Cathedral, the V&A, the Shard and now Leadenhall.

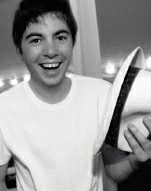

With my son Ab, who has worked with me on exhibitions, books and interiors.

Ab has worked with us to adapt the house, as it has evolved over the years. Now in partnership with my cousin Ernesto Bartolini, Ab’s design practice also worked on both my recent exhibitions – Inside Out at the Royal Academy in 2013, and From the House to the City at the Pompidou Centre in 2007 – and helped create the visual language of this book too. Like me, he is dyslexic, though his spelling is even worse than mine; I asked once why he didn’t use his spellchecking software, and he replied that the programmes couldn’t even guess what words he was typing. We talk nearly every day about buildings, art and design.

Below the main living areas, on the ground floor there is a flat that Ruthie’s parents, Fred and Sylvia Elias, moved to from New York a few months after we completed Royal Avenue. They lived there for the rest of their lives – independent, but near enough at hand to receive regular visits from their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who were always indulged with love. In the early hours of the morning, Roo and later Bo would come to wake us up in our top-floor bedroom, and would be persuaded to creep down the spiral stairs to see their grandparents instead. As Sylvia used to say, ‘It’s a grandparent’s role to say, “Yes”’ – a role we now have with our 12 grandchildren – Eve, Thea, Merle, Rita, Ivy, Asa, Sasha, Ella, Lula, Ruby, Mei and Coco.

Thames Wharf

Upriver is Thames Wharf, an easy four-mile bike ride away, which was home to my practice for as long as Royal Avenue has been home to my family.

After returning from Paris, we had found a Notting Hill office, a beautiful white brick building with its own courtyard in a quiet mews, which had been used as the location for David Hemmings’ photography studio in Antonioni’s Blow-Up. Our original aim was to cap the office size at 30 – the number you could reasonably fit round a large dining table. But by the early 1980s, we had rapidly grown to 60; we were busy with the closing stages of the Lloyd’s Building, Coin Street, the National Gallery competition, and industrial buildings for Inmos, the Cummins Engine Company and PA Technologies. We needed more space.

John Young loved to explore London’s waterways on his bike, and one day he came across a dilapidated collection of riverside oil warehouses backing on to quiet residential streets, with views of Hammersmith Bridge and the ornate Harrods Repository on the other side of the Thames. John, Marco Goldschmied and I bought the site, and then sold half of it to a developer for housing (which we designed, giving John the chance to build his penthouse flat on the top floor). In this way, we could cross-subsidise the redevelopment and extension of the main block, which would house the practice. Working with Lifschutz Davidson, we created a two-storey light-filled arch on top of the building.

Thames Wharf had been a run-down industrial dead end; we opened it up to the river and the city. Having battled for years for better public space, we finally had the opportunity to create our own place for people. The courtyard garden between the office and the River Café is open 24 hours a day, with a picnic table looking out over the river. It was designed by my old friend Georgie Wolton, not just to enhance the buildings and their setting on the banks of the Thames, but also to act as a safe, enclosed kitchen garden, where children can play while their parents eat, drink and talk at the River Café.

We wanted Thames Wharf to feel like part of the city, not a reclusive enclave like so many industrial buildings were in the past and so many riverside properties are today. And we wanted that spirit of openness and relaxation to permeate our practice inside the building too. Hugh Pearman likes to tell a story about his fellow critic, the late Martin Pawley, returning from visiting us one day. ‘How was it?’ asked Hugh. ‘Oh, you know,’ said Martin with an expansive gesture. ‘Troubadours strumming guitars in the corridors…’ We didn’t really have any corridors at Thames Wharf, but it’s just about right in other ways.

The River Café

In 1987, as we were finishing the conversion works at Thames Wharf, one of the leases in the building alongside ours came up. Ruthie and I wanted to develop a community with a place to eat together, so we looked at a number of restaurants who wanted to move in, but none of them seemed quite right. The only thing worse than no restaurant would be the wrong sort of restaurant, and in one of those life-changing moments, Ruthie said, ‘Maybe I’ll do it.’ She sought out Rose Gray, whom I had met with Su more than 30 years previously.

Neither Ruth nor Rose had experience in restaurants, but both shared a passion for Italian cooking. Rose had lived for three years with her family in Lucca in the early 1980s and had helped open the kitchen at Nell’s nightclub in New York, and Ruthie had learned from my mother (an exceptional cook, who had herself only started cooking when she came over to England in 1939) and from spending hours in the kitchen with my family in Florence.

Rose and Ruthie in the River Café. From the beginning everyone has worked together to prepare the day’s menu.

In the beginning, Ruthie and Rose offered sandwiches as well as hot food, taking it in turns to cook the day’s dishes using a domestic oven. Some of those – including the grilled squid with chilli, and the pear and almond tart – are still on the menu today. From the beginning they had clear principles: to cook regional Italian food, to change the menu every day, for everyone to participate in the process of preparing and serving meals, to be seasonal and sustainable, and to source the best ingredients. The River Café menu had its roots in Tuscany, though later both menu and wine list extended to other parts of Italy.

Thames Wharf was out on a limb, and even London cabbies had trouble finding it at first. The restaurant was also constrained in its opening times by our location in the middle of a residential neighbourhood. The River Café started off by operating only at lunchtime, initially for people working in the warehouses. Then it opened to the public at lunchtime, then in the evening too, first until 11p.m. but now until midnight. Its reputation grew, and after seven years it began to make a profit. Ruthie and Rose became like sisters, finishing each other’s sentences, laughing together, and sharing the same blend of warmth towards their team. Their unflinching commitment was to make every dish just as it should be, day after day.

Rose was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2003, but continued to work closely with Ruthie, at the River Café and on their cookbooks. Even when she was seriously ill, they would discuss the menu every day, and she would taste and acutely critique dishes that were sent to her. She died on 28 February 2010.

Ruthie by the bright wood-fired oven at the River Café, where everything from turbot to pigeons to langoustines is cooked.

Lunchtime at the River Café.

Thames Wharf, with people eating on the River Café’s terrace, chatting in the sunken garden, or just strolling along the river bank.

John Young’s beautiful penthouse flat at Thames Wharf includes a sleeping platform suspended above the seating area.

The RRP offices at Thames Wharf, with the roof extension designed with Lifschutz Davidson. I miss the view from the top floor over the Thames.

My son Zad reads ‘The 80 Colours of Richard Rogers’ at my 80th birthday celebration.

The River Café cooks the Italian food that I love most, and it has a unique ethos and atmosphere. The long room is suffused with light and reflections, at once animated and calm. Outside, on a summer’s afternoon, the garden feels like London’s best secret: hidden away down residential backstreets, with children playing on the lawn while their parents eat under the trees among the planters filled with fresh herbs and vegetables. It became a part of the office, a place to have a quiet meeting with partners, to sketch designs on paper table cloths, to meet and talk with young architects who had joined the practice.

Everyone at the café works in daylight and can walk down to the river for a break. If restaurant kitchens have a reputation for machismo, then the River Café is the opposite. It is based on communication and teamwork. When you go there first thing in the morning, the waiters are helping to prepare the food, partly so that they can understand it and talk about it to customers, but also to reflect the spirit of collaboration, of joint endeavour, that Rose and Ruthie instilled.

The spirit of the River Café is well-captured in the two films that Zad, my second son, made. Zad is a television and media producer. Together with Harriet Gugenheim, Ben’s wife, he made a movie for Ruthie’s 60th birthday, which showed the whole family singing together, and wrote a moving and beautiful poem (The 80 Colours of Richard Rogers), which he read out at our family celebration of my 80th birthday.

Holidays and Family

Both Ruthie and I love our work, and everything, even holidays, is a continuous part of the whole. I don’t garden, cook or have any hobbies; my family is my focus. Now that our sons, their partners and our grandchildren are all gathered together in London, we try to see them every week or two, and speak every day. If Ruthie is away or working in the River Café, I will invite myself to one of their houses for supper.

When the children were young, we took them on adventurous trips – to Moroccan deserts, Mexican pyramids and Nepalese temples – and they’ve all inherited this spirit of adventure. But over the years it has become more important for us to return to the places where they grew up, and can now bring their own children, and where we have built strong friendships and feel that we are part of the community.

Every August we visit the same farmhouse, converted by Giorgio and Ilaria Miani, two hours south of Florence, which we have rented for the past 20 years. The Val d’Orcia is a Unesco World Heritage Site, a stunning unspoilt valley, surrounded by rolling hills and dominated by the 1,700m Monte Amiata. Val d’Orcia was historically one of the poorest parts of Italy, held back by the heavy clays that formed its soil. The landscape was untouched by man until the 1930s, when Iris Origo, a wealthy Anglo-American woman, came to the valley, set up schools and health centres, and taught the local farmers modern techniques to help them enrich and work their land. Her book, War in the Val d’Orcia, is a fascinating account of her life during the Second World War, when she sheltered and helped many escaped prisoners of war.

The house is within 30 minutes of four beautiful villages. Montalcino is a medieval fortress town now known for its excellent wine, Brunello di Montalcino. Montepulciano, which sits on a hilltop full of wine cellars, overlooks the magnificent church of San Biagio, with ‘servant’ towers that could have been devised by Louis Kahn. San Quirico d’Orcia surprises visitors with its simple high street and beautiful sixteenth-century gardens.

With my son Roo and his wife Bernie in Mexico.

The hilltop town of Pienza is an early masterpiece of Renaissance town planning. It was designed in the fifteenth century, when the architect Bernardo Rosselino (a colleague of Leon Battista Alberti) was commissioned by Pope Pius II to remodel his native village, then called Corsignano. Rosselino devised a beautiful square framed by the town hall, a papal palace, a cardinal’s palace and the cathedral, intersecting with an elegant main street, the Corso Rosselino, which runs between the town’s two gates. There is a story that, when the work was done, Rosselino apologised to the Pope for not responding to any of his letters. Pius replied, ‘If you had done, I would not have had this piece of heaven!’

There is rarely a bed free as family and friends converge, and now our grandchildren visit with their friends. For a month, we enjoy swimming in the pool, long lunches, walks in the cool of the morning, a passeggiata and sunset drinks in a nearby village. Conversations and debates go on long into the evening, and I start each morning watching the sunrise from the terrace, as I work through papers and projects.

In 1993 our love affair with another country began when Ricardo Legorreta invited us to visit Mexico – we were immediately entranced by its light, its bright colours, its open-minded architecture. We first stayed in a dramatic house overlooking the Pacific, designed and owned by Carlos and Heather Herrera. Since then, we have travelled all round, and in recent years we have more or less settled in Oaxaca, staying at Norma and Rodolfo Ogarrio’s beautiful courtyard house in historical Oaxaca City, visiting Monte Alban, and spending Christmases with family near Puerto Escondido.

Vernazza a jewel in the Italian Cinque Terre, and a treasured place for all the family.

Bo was living there when a landslip devastated the town in 2011.

Roo and Bernie were married there.

But there will always be one person missing. Bo, our youngest son, was born in Tucson, Arizona, in 1983. We held him in our arms when he was just 36 hours old. It was one of the most moving moments of my life; though he was adopted, he immediately felt like part of me. From a young age, Bo was passionate about the world around him, in everything from the intricacies of London Transport to the solar system, and had an incredible flair for languages – I remember him singing ‘Happy Birthday’ in Arabic. He loved school, but he hated exams, was suspicious of any trace of pretentiousness, and sought the company of his family and friends.

Bo worked in my office for three years, alongside his oldest friend Lorenz Frenzen, but began spending more and more time in Vernazza, a beautiful small village in the Cinque Terre on the Italian Riviera, that we have been visiting almost every year for 50 years. Unlike the constant arrivals and departures of Tuscany, Vernazza, which is only accessible by train or boat, is where we go just to be with family and close friends, enjoying the beautiful cliff-top walks to the next villages and the delicious food prepared by our good friend Gianni Franzi. When Roo and Bernie were married in the piazza there, the whole town joined the celebrations.

Bo had settled in Vernazza by October 2011, with his own close-knit group of friends, and was working in his friend Alberto’s internet cafe. Everyone joked that ‘Rogerino’ (as he was known over there) was destined to one day become mayor. But one afternoon after months of dry weather, there was a colossal rainstorm, and a huge landslide, which killed three people. Bo helped people from the water, and was then evacuated by a Red Cross boat (other routes were blocked). I spoke to him that evening when he’d arrived in nearby Viareggio, and was so relieved to hear he was safe. I go over and over that call in my mind, and the terrible call we received from his friend Luna the next morning telling us that Bo had had a seizure and died.

There is no recovery from the death of a child. Death can push people apart or bring them together; we were brought together as a family. At the ‘Remembering Bo’ memorial at the River Café a month or so after his death, Bo’s brothers and sisters, and his friends from Vernazza, all spoke about their memories of him, and the sadness of a life cut short. His twelve nephews and nieces joined together to sing ‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’, reflecting his love of travel, and ‘I Will Survive’, his favourite song.

In November 2012, Ruthie and I spent a day choosing a tree for Bo’s ashes, picking an Italian olive, which we planted above his bedroom on our roof terrace in Chelsea. Renzo and I designed a corten steel planter and a white cedar bench opposite it. Ruthie and I often go up there to sit together quietly with our memories, or to say goodbye to Bo when we go away. There are further trees at our dear friend Paddy McKillen’s home in Provence, where he had provided us with sanctuary in the weeks after Bo’s death, at Renzo’ new wing for the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, and on the slopes at Courcheval. Every year on the anniversary of Bo’s death, we travel together as a family on the number 19 bus from our house to the River Café, and then come home to talk about Bo, and sing songs around the tree. As a way of honouring Bo and his relationship to Vernazza, I worked with my cousin Ernesto Bartolini and the people of the town on a series of schemes to restore the streets and squares that were destroyed in the landslide.

With my brother Peter in 2016.

Writing this book, I have found myself thinking more and more about my own parents, and my brother. Peter and I have become much closer as adults. He was born 15 years after me – a huge gulf when you are young. I remember my pregnant mother asking me whether I wanted a little brother. I cruelly replied, ‘I’d prefer a dog.’ I used to say that I was more like my mother, while Peter, the analytical engineer, who co-founded the developer Stanhope with Stuart Lipton, and is now his partner in Lipton Rogers, was more like my father. But now we see more of each other in ourselves. His understanding of the process of building is phenomenal – he chaired Constructing Excellence, the national body dedicated to improving standards in construction – and his attention to detail is the perfect foil to Stuart’s exceptional vision and passion for cities.

I have also realised more clearly how huge my parents’ influence was. I spoke to Dada every day, and can easily see how her love of art, modernism and colour – embracing rather than recoiling from the new – has informed my choices, but I can also detect, just below the surface, the steel that drove my father Nino to climb mountains and bring his family to England.

My father died in 1993, my mother five years later. Nino lost some of his mental acuity as he aged – a tragedy for someone who set so much store by the power of the human intellect – but Dada remained sharp even at the age of 90, as the cancer that killed her spread. She felt people should age with dignity rather than trying to make themselves look younger, but she remained strikingly beautiful, maybe more beautiful as she got older; when she was in her 80s, Issey Miyake asked her to model for him. When it became clear that death was imminent, I stayed with her at Parkside, sleeping in the same bed, and talking about her life, about mine. Everybody was convinced that I was going to go to pieces when she died, because we were so close, but after the experience of spending that last month with her, I could accept her death peacefully.

In her last days, Dada told Ruthie that she should use more cream on her face and less herbs on her fish. And one of the last, and most characteristic, things she said to me was that the problem with death was that she’d miss seeing the future.

Our granddaughter Mei using the staircase as a climbing frame.

Piazza del Campo in Siena, which started as a marketplace between neighbouring settlements, and later became the centre of political and civic life in one of the great Renaissance cities.