9Public Spaces

Nothing gives me greater pleasure than walking and pausing in lively public spaces, from small alleyways to great European squares. Public spaces are places for all people and stages for public life; the public realm is at the heart of our life as social animals; it enables the meeting of friends and strangers, for the exchange of goods and ideas, for political protest and for intimate moments.

Public spaces are the lungs of the city, an expression of society and a force for democracy, the places where there is a mix of activities and people from all classes, all creeds and all races. Whether it is Zuccotti Park in New York, Tiananmen Square in Beijing, Taksim or Tahrir, public spaces are where people can come together to debate, to demonstrate, to demand change. Plaza de la Constitución – known as ‘the Zocalo’ – has been the centre of civic life in Mexico City since pre-Colombian times. Every parliament should have space outside for public demonstrations; the fact that the UK government seeks to banish demonstrators from Parliament Square is an embarrassment.

Cities are civilised by the treatment of their public domain – their sidewalks, parks and rivers. When we visit a foreign city, these are the places we remember, as much as the façades or interiors of individual buildings. Architecture is not about discrete buildings viewed in isolation, but about the experience of cityscapes, about how buildings respond to topography, frame space and create the structure of cities. I love the way that narrow alleyways, with the sunlight creating a play of light and shadow on buildings, pavements and pedestrians, suddenly explode into the dazzling light of piazzas.

Good architecture should always seek to create well-designed public spaces, filling in and framing spaces so that streets and squares can become living rooms without roofs for citizens. But in today’s all-commanding market economy, affordable housing and public space is constantly under threat – eroded and dehumanised. The architect and his team, the client and the city planner, need to defend these spaces, and champion their civilising effect on the city.

One of my first memories from my pre-war childhood is of looking out from my grandfather’s house in Trieste. Opposite there was a cafe, of course, and every morning at about 7a.m., they pulled their shutters up, and would put a table and chairs outside, and a man would come and sit down. He was an accountant, and the pavement outside that cafe was his place of work. I thought it looked like the ideal job: your food and your coffee were looked after, and your customers and friends would come to you. It’s the same in Djemaa el-Fna, the huge marketplace in Marrakesh, and in Indian cities, where clerks sit outside with typewriters, helping their clients with forms and letters.

Public space – big or small, noisy or quiet – reflects civic values. Greek and Roman civilisation centred on the experience of citizenship in the agora and forum. As settlements transformed into cities, the spaces of day-to-day activity – from trading goods to washing clothes – became the centrepieces of civic life.

The Agora and the Birth of Civic Life

Though the Renaissance had its roots in Florence, the city of my birth, where Masaccio, Donatello, Brunelleschi, Alberti and Dante flourished, the birth of democracy was some 2,000 years earlier, in classical Athens. Every time I visit the city, I head straight to the Agora, the ancient marketplace and historic centre of civic life, to the Acropolis and the adjoining museum. I am always struck by the modernity of culture and philosophy, but also amazed by the public spaces and buildings that stand elevated above the city, built in a dramatic moment of creativity millions of years after the birth of man.

Time does not stand still, however. On 26 June 2016, I went back to Athens, not just to revisit the Acropolis, but also to attend the opening of Renzo Piano’s new Stavros Niarchos Opera House and Cultural Centre. This too aspires to be something more than a building, more than just architecture. The building is completely contemporary, topped by a great white horizontal sail, held delicately in place by a perfect steel structure, creating a shaded public space with amazing views out across the city. From its elevated position above the coastal plain, the building looks back at the Acropolis.

The Passeggiata and the Piazza – Public Space in Italy

Public spaces have been integral to Italian cities for centuries, and it is to these streets and piazzas that I return again and again. They are the stage for that most Italian ritual, the passeggiata – the daily parade in the cool of the early evening.

Verona has some of the most beautifully designed pedestrian streets. The same stone is sculpted to fulfil different functions: kerbstones, grilles, drains, low splash panels of shop fronts, planters. The consistency of materials and finish lends a calm and elegant quality, so unlike the frenetic mess of street furniture, paving slabs, tarmac and concrete that disfigures many cities’ thoroughfares. I met one man who said he moved from southern Italy to Verona, simply for these exquisitely paved streets.

Many Italian public spaces have long histories as meeting places. The Piazza del Campo in Siena, which today hosts the Palio horse race twice a year, was established at the meeting place of the three hillside settlements that formed the city. It was a marketplace, and then a place where women would gather to wash their clothes in the water channelled through Siena in aqueducts and canals. Its slope still represents the natural topography of the land and water today.

The nine segments of paving that radiate from the Palazzo Publico represent the Governo dei Nove, the merchants who ruled Siena in the fourteenth century. The marketplace was neutral territory between powerful families’ strongholds; the centre of commercial and social life grew organically to become a centre of civic and political life, like the Agora in Athens or the Forum in Rome. The Piazza del Campo has been a great influence on my thinking about public spaces, but one that I absorbed almost without noticing it.

The centrality of public space was rediscovered in the Renaissance: more and more private spaces became opened up, like the great parks in London, and the piazzas and streets mapped by Nolli in his 1740 plan of Rome. When Nolli drew his map, around 60 per cent of Rome’s footprint was open to the public – markets, squares, parks, churches, baths, theatres. Rome was an open city.

Campidoglio is the site of Rome’s ancient citadel, its geographical and ceremonial centre. It remained a centre for government (Rome’s City Hall is still at one end of the square), but had become dilapidated by the sixteenth century, when Michelangelo was asked to redesign it by Pope Paul III.

Michelangelo’s design emphasised Campidoglio’s position as a lynchpin between the Forum of ancient Rome on one side, and ‘modern’, papal Rome on the other. He remodelled the buildings surrounding the irregularly shaped and sloping piazza, creating a beautiful flight of steps (the cordonata) leading up from papal Rome to the capital, connecting the two cities. The piazza was paved in a stunning pattern of interlocking circles in travertine marble, seemingly an oval but actually egg-shaped to fit in the irregular space. Marking the centre of the piazza is a statue of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, mounted on a horse. I visited once with the painter Philip Guston, who commented with enthusiasm on the horse’s ‘stupendous rump’.

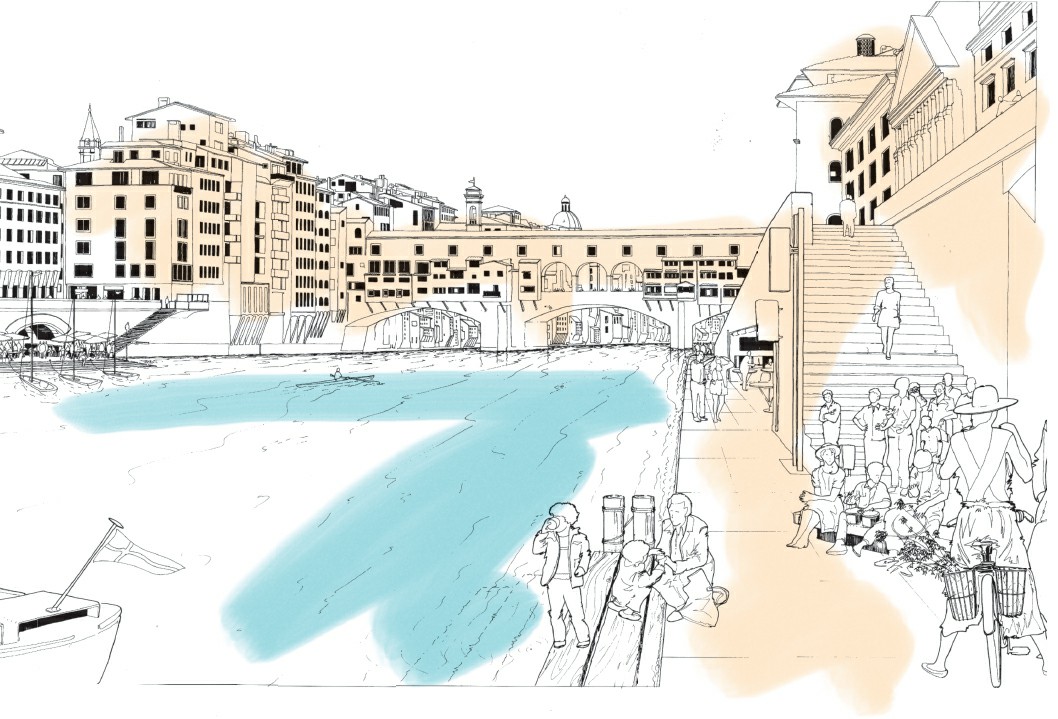

Our masterplan for the banks of the River Arno in Florence, the city of my birth, was a precursor to the exhibition London As It Could Be (1986).

We proposed a linear park, passing under the Ponte Vecchio, with performance spaces, cafes and green spaces, to bring life back to the river banks, cut off by heavy traffic on the embankment. Heritage considerations prevented the plans from being realised.

Campidoglio is small but exquisitely proportioned. The views west are breathtaking, particularly at sunset, as you see all Roman history laid out before you, linking not just centuries but millennia.

Campidoglio was designed as a totality, but many of our most loved public spaces have been the result of accretion, not creation, growing over time, enriching themselves with new buildings and uses, creating harmony from sometimes startling contrasts. There is no better example of this than Piazza San Marco, whose apparent harmony is actually composed from dramatically different buildings. The square, alongside St Mark’s Church and the Doges’ Palace, was first cleared in the early thirteenth century, and was enclosed by government and charitable offices on three sides, built over three centuries. These buildings, which have been changed and updated over time, all had arcades and space for shops on their ground floor, giving life to the public space in front of them, and creating a coherence and consistency to the piazza’s north, west and south sides.

Later in the thirteenth century St Mark’s Church, on the east side of the piazza, was extended and embellished with domes and turrets, and encrusted with marble, amazing mosaics and sculptures. More than a hundred years later, the tall campanile was added, an addition that must have seemed colossal and alien at the time (and would never have received planning permission today), but now looks integral.

San Marco’s architecture is an ornate mix of styles, and a living illustration of the point that harmony can lie in contrast as well as consistency, but it suits the city’s damp and sometimes grey climate more than Palladian classicism, which needs sunshine to define its sharp lines. It is a tribute to the creativity that city-states can demonstrate, and a symbol of mercantile prosperity; through the window of the smaller piazzetta alongside the Doges’ Palace, the piazza looks across the Grand Canal to Palladio’s San Giorgio Maggiore, and beyond to the sea – the source of Venice’s power.

I have been visiting Venice, the pre-eminent pedestrian city, ever since I was a child, when we used to go with my grandparents. Two of the cafes – Florian and Quadri – are still there today. I remember my grandparents explaining that one was left wing and the other right wing; but I could never remember which is which, and still can’t. It is the perfect compact city without trains or cars, where one walks or takes a vaporetto from place to place, shimmering in its mysterious soft blue-grey light. Nowadays, Ruthie and I visit in the winter, when the city is melancholic and wrapped in mist, often to remember our son Bo’s birthday. It is never more beautiful than at dawn, or when floodwaters drive tourists away and create reflections of light and buildings throughout the city.

The Erosion of Public Space

In the twentieth century, public space came under attack from two enemies. Urban enclosures privatised what had once been public, and replaced ‘open-minded’ mixed streets of overlapping functions with sterile, single-use precincts designed simply to maximise consumption and profit – heavily policed and exclusive to those with enough money, the right clothes or the right coloured skin. I was so shocked on my first visit to Houston in 1983, where we had been commissioned to design a new shopping mall. In the heat of a Texan summer, the rich moved from air-conditioned homes, into air-conditioned cars, and then into air-conditioned underground shopping malls with security guards posted at entrances. The poorer people lived above ground in a parallel universe of baking hot streets that were derelict and poorly maintained.

This dereliction of the public realm epitomises J. K. Galbraith’s analysis of private affluence and public squalor; social injustice is laid bare. Even in London, which has changed beyond all recognition since I first arrived in 1939, we have only managed to build one major new public park in 100 years, and that took an Olympic Games. Meanwhile, the garden squares of Kensington and Belgravia remain locked, out of reach to everyone apart from property owners, their nannies and children. I argued for this to change when Ken Livingstone was mayor, but to no avail.

The car is the other enemy of our public space, and of cities as a whole. It has destroyed the spirit of community, eaten up the public realm, and demanded that cities be redesigned to meet its needs. Public space became road space, and the meeting places of people were torn up to meet the car’s insatiable appetite for ring roads, roundabouts, highways and car parks, ripping the souls out of cities. Great highways severed communities and gobbled up land, occupying up to 60 per cent of the land area of cities like Los Angeles.

In the past 20 years, we have seen a slow revolution, rolling back the dominance of the car, and giving the pedestrian and cyclist, not the motorist, the upper hand. A lot of this is about simple changes to redress the balance: taking down the barriers that pen pedestrians like sheep and allow cars to dominate; creating raised extensions of pavements where these cross roads, so that it is pedestrians who have the right to move around the city smoothly; redesigning our roads to make space for cyclists. It is no accident that the cities voted the most liveable and the most enjoyable to visit are those where the car is controlled and the public can dominate the street.

Beginning to reclaim our cities from cars has already enabled the resurgence of downtown districts, and made our cities cleaner, healthier and more vital. Autonomous vehicles, which are forecast to be commonplace within ten years, will change our cities further, reducing deaths and injuries, transforming public space, increasing productivity and creating new industries.

The Danish architect Jan Gehl has made it his life’s work to analyse and understand how people actually use public space, so that we can design streets and public spaces appropriately. His work has transformed Copenhagen, and cities from Melbourne to São Paulo have sought his advice in trying to rehumanise their public spaces. He came to London in 2004 and surveyed a cross-section of streets and squares, including Tottenham Court Road, Trafalgar Square and Waterloo, to see how the congestion charge could be used to create a better city centre for people. London’s still fractured governance means that not everything was implemented – and Jan remains very critical of London’s public realm – but his recommendations helped to shift the debate, from streets for cars to streets for people.

I have always seen public space as a human right, like the right to decent healthcare, food, education and shelter. Everyone should be able to see a tree from their window. Everyone should be able to sit out on their stoop, or on a bench in a local square. Everyone should be able to stroll to a park where they can walk, play with their children or just enjoy the changing seasons, within a few minutes. A city that cannot provide these rights is simply not civilised. Good public space is open-minded, to use the terminology developed by philosopher Michael Walzer; it does not try to define specific activities, but can accommodate anything – lovers meeting, quiet mourning, children playing, dog walking, political debate, reading, ball games, demonstrations, snowman building, picnics, exercise classes, dozing. Whether large or small, good public space is human in scale; the vast plazas beloved by dictators are designed for tanks and military parades, not civilised human interaction.

Public space is not just a civilising aspect of our cities. It makes a tangible difference to people’s lives. Research undertaken for the UK’s Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment found that people who could walk in parks or see green space from their windows live happier and healthier lives than those who cannot.5

London’s Wasted Spaces – Coin Street, Trafalgar Square, South Bank

London has some of the best public spaces in the world, as well as some of the worst. The Royal Parks and Hampstead Heath are some of the most beautiful green spaces of any city, and to walk through them as they are thronged with people on a summer’s evening is a delight. Unlike Central Park in New York, which is carved out from – and contrasts with – New York’s strict grid system, London’s great parks responded to the more human scale of the city, sometimes even creating an arcadian illusion of rurality. There are magnificent set pieces too. One of my favourites is the view from the bridge in St James’s Park, with the domes and cupolas of Whitehall sitting alongside Big Ben and the more recent addition of the London Eye.

But for many years, these great parks were the exception. London’s street life was as good as non-existent; social life was shut indoors, in smoky male-dominated pubs and clubs, not in the people-watching pavement cafe society of Paris or Rome. Leicester Square, Piccadilly Circus, Trafalgar Square were celebrated in song and popular culture, but bitterly disappointing when you actually saw them – mean gyratory systems for cars and buses.

At London’s heart was its most neglected public space – the River Thames. The city of heavy industry and docks barred the public from the riverside. And, while the water quality had improved hugely since the ‘great stink’ that prompted Joseph Bazalgette to build proper sewers in the nineteenth century, the river was still a dirty and lifeless drain in the 1970s. The Festival of Britain had made a small inroad into the South Bank; its legacy the Royal Festival Hall, later joined by the National Theatre and National Film Theatre. But this remained an isolated glimmer of light, like an enclave or trading post in hostile territory, its back turned on south London. With changes in shipping and industrialisation, cities have begun to rediscover their waterfront. In Barcelona, new beaches were created for the 1992 Olympics. In Sydney, our practice has masterplanned and designed a new urban district on the former docks at Barangaroo, overlooking the spectacular Darling Harbour.

In London, the rediscovery of the waterfront has been a slow process. Our involvement began in 1978, when we were approached by Greycoat Estates, headed by Stuart Lipton. Greycoat had prepared a scheme for speculative offices to run along Coin Street, behind Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre and the more nondescript buildings alongside it. The local community was up in arms about the encroachment of offices into their neighbourhood, and the lack of housing provision, and were heavily supported by Ken Livingstone, then leader of the GLC.

With Norman Foster at the Team 4 Reunion at the River Café in 2013.

The planning application was due to go to a public enquiry in early 1979, where Greycoat’s legal team feared it would be turned down, and we were asked (at the suggestion of RIBA president Gordon Graham, who had decided to promote Norman Foster and me as the future of British architecture, and helped both of us achieve some of our most important early commissions) to help develop a design that could get permission. We were tied up with Lloyd’s at the time, so we agreed that Marco Goldschmied, one of the three partners at the time, would meet up with the developers to decline politely. He came back saying that he had tried and tried to say ‘No’, but it had not worked. So, I tried, and got no further; Stuart was very persuasive. I insisted that we be allowed to revisit the balance of public and private space, to connect the new development to the riverfront, to add in housing, to build a bridge over the Thames. To my surprise, they agreed to everything.

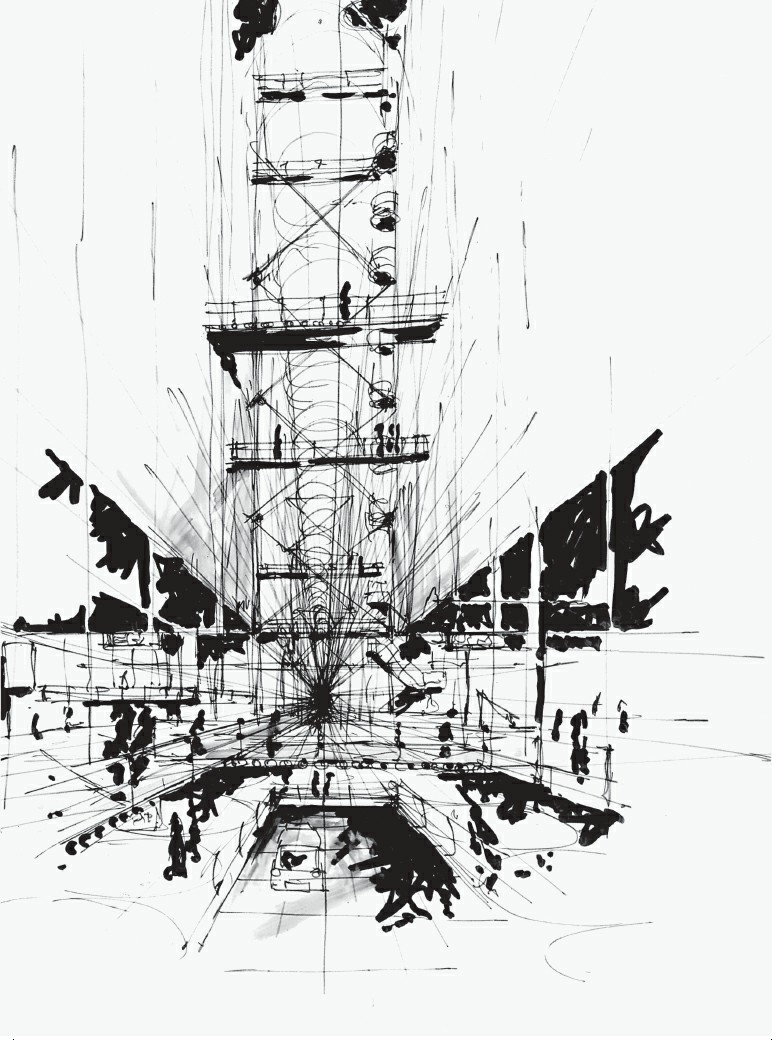

I appeared at the first public enquiry armed only with initial sketches. We lost, but Stuart decided to try a second application, with a legal team that included Garry Hart, who I worked with for many years and who later became an adviser to Derry Irvine, Tony Blair’s Lord Chancellor. Working with Laurie Abbott and Andrew Morris, we developed plans for a galleria running from Waterloo station down to the river, with shops and public space at ground level, offices above, service towers of varying height providing a new backdrop to the South Bank, and 300 homes for local people on the south side. We also proposed a pedestrian bridge, connecting the development to the north side of the river by Temple, to bring life to the South Bank and create a grand passegiata from Waterloo station to Aldwych.

These plans didn’t satisfy the protestors, who only saw the office developments, rather than the revitalised public space that we were trying to create or the housing to be built alongside. Coin Street was a flash point in the gradual encroachment of office space outside London’s established city centre, into areas that were traditionally dominated by working-class housing. It was an uncomfortable surprise to find myself arguing a developer’s case against community groups (supported by Labour GLC leader Ken Livingstone) in the planning enquiry, but I found that I could deal with the cut-and-thrust of cross-examination quite well – a legacy of growing up in a household where debate and discussion were prized. Our practice was moving offices at the time, and the protestors heard about this and came to picket our moving-in party; Ruthie invited them in, and we had a great evening dancing and drinking, before returning to battle in front of the planning inspector the next morning.

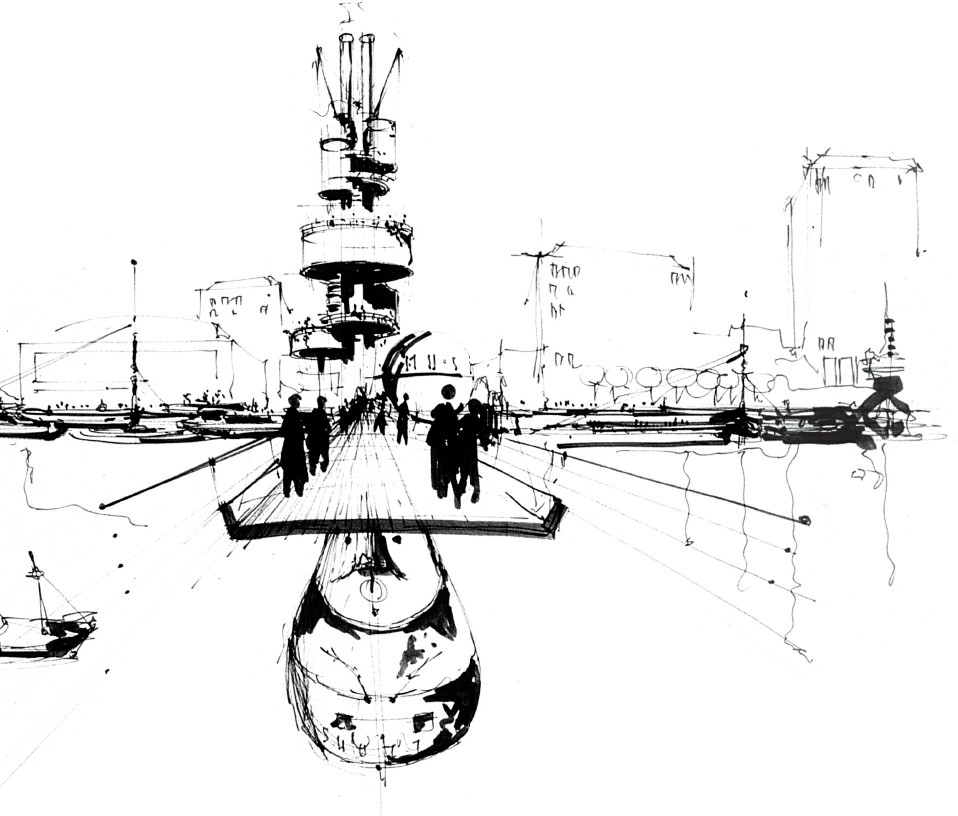

The walkway would have been within a glazed gallery, containing offices, shops and affordable housing.

Our plans for Coin Street would have created a new walkway from Waterloo Bridge to the Thames, with a pedestrian bridge connecting to the North Bank.

Our entry for the National Gallery extension competition in 1982 examined how we could strengthen the link between Leicester Square and Trafalgar Square.

Eventually, the planning minister Michael Heseltine granted permission both for our scheme and for the community housing scheme. It seemed a very English fudge, to give two schemes planning permission. I suspect his expectation was that it would only be the developers who could build their scheme. Greycoat Estates, who owned some but not all of the land, prepared to implement their plans, but the GLC intervened, providing the money to enable Coin Street Community Builders to buy the land, and take their scheme forward. This scheme stalled, so Greycoat were approached again, but by that stage Stuart had moved on and they had lost their appetite for the project. Now, of course, the Coin Street development and the Oxo Tower are at the heart of the incredible urban walkway that has been opened up on the South Bank, passing from Westminster to London Bridge, connecting Tate Modern, the South Bank Centre and Borough Market, and thronged with crowds every weekend.

On the other side of the river, Trafalgar Square, once the heart of an empire and strewn with imperial monuments, was essentially a congested roundabout in the early 1980s. Beyond political demonstrations and New Year’s Eve celebrations, few ventured onto its pigeon-infested central areas. You had to take your life in your hands to get over the road, and there was nothing to do or see if you made it.

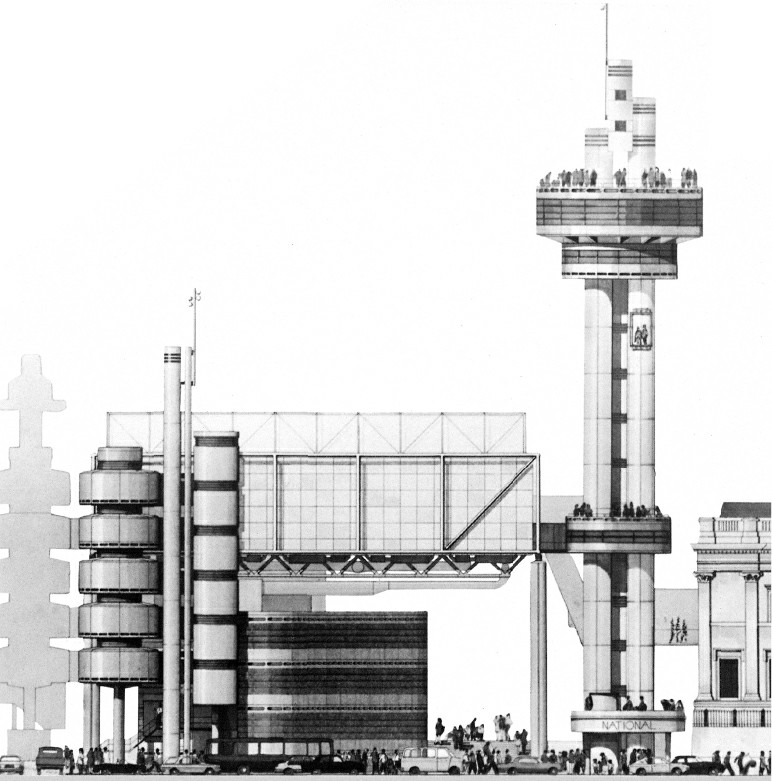

On the edge of this drab gyratory, the National Gallery needed space to expand. But in keeping with the Thatcherite spirit of the age, the additional gallery space was to be funded by building offices, and developers were invited to enter a competition together with architects. Speyhawk approached us, and we developed a scheme that lifted the new gallery space high in the air, with natural lighting above, and flexible servicing from below. Beneath this we showed office space, designed to be detachable, so that it might be replaced by gallery space if funding became available under a more enlightened administration.

A model of our scheme, showing the public space created underneath the raised galleries, with the walkway connecting through to the centre of Trafalgar Square.

Our National Gallery scheme proposed raising the galleries off the ground, to maximise natural light and public space. Below them, commercial offices would be built to cross-subsidise the development, but could be replaced by galleries or other uses over time.

To one side, we placed an observation tower with a cafe on top, offering Londoners a vantage point in the heart of the city, and also forming a counterpoint with Nelson’s Column, the classical cupola of the gallery and the elegant spire of St Martin-in-the-Fields. A leader in The Times praised our entry as ‘large in conception, bold in execution, a gesture of architectural confidence’, though talked of ‘bathos’ in the juxtaposition of a coffee shop with a spire pointing to heaven and a statue of a great war hero. But creating space for all people seemed every bit as important to me as glorifying a deity or an admiral.

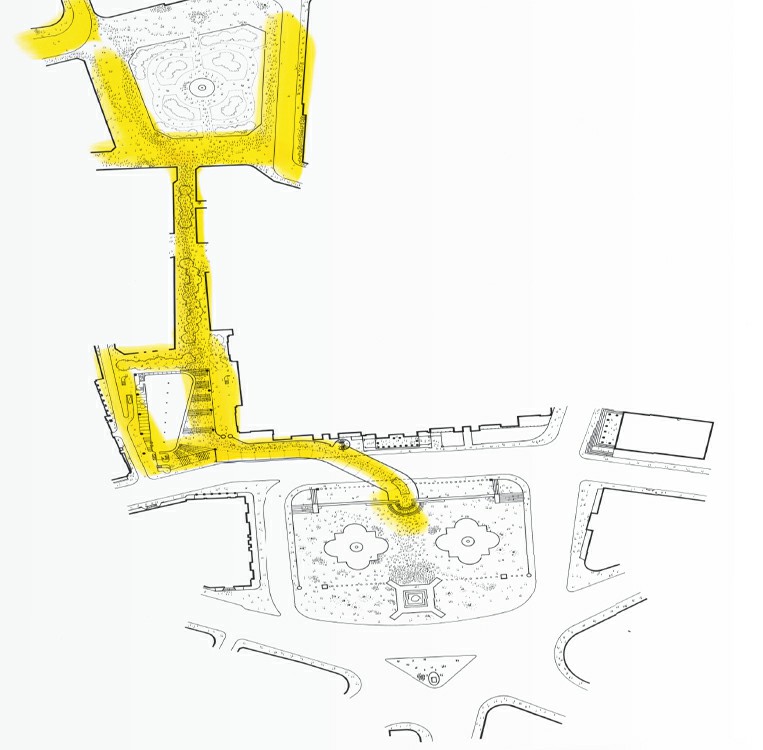

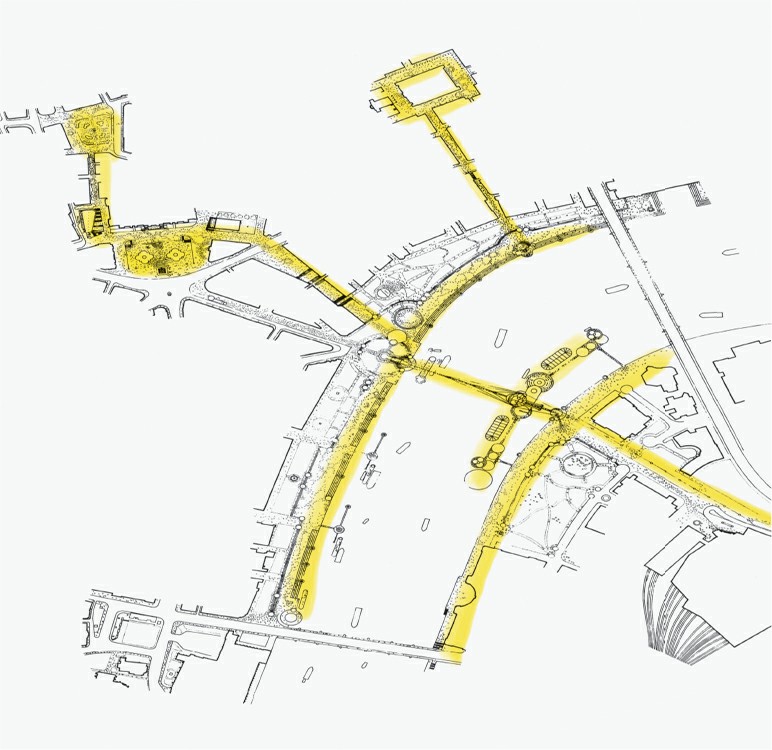

We also undertook an extensive study of the local roads, looking to see whether there was any way of pedestrianising Trafalgar Square. We weren’t able to justify pedestrianisation to our client, but we proposed lowering the ground under the extension, to create a sunken piazza, with an underground gallery leading south beneath the road into the heart of Trafalgar Square. To the north, we made new pedestrian connections with Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus. We wanted to give London – 32 towns without a town square – the type of shared civic space that a capital city deserved.

RIBA president Owen Luder described our scheme as ‘Sod you!’ architecture, a remark that was intended to praise our lack of compromise, though the epithet did us damage in the public debate. Our proposals were more discussed for their striking architectural form than for our attempts to complement the monumentality of Trafalgar Square or to create new walking routes for Londoners. In the public exhibition, we attracted most votes, both for and against, though Hugh Casson, the competition chairman, hinted that we were not popular among some important people.

Our scheme came second to a design by Ahrends, Burton and Koralek, which adopted a similar language, but was never built, following the Prince of Wales’s denunciation of it as a ‘monstrous carbuncle’. These remarks, which did terrible and lasting damage to the reputation of one of the best studios of our time, stopped the process dead in its tracks. The National Gallery gave up on the idea of a developer-funded extension, and launched a new competition, restricted to architects who might be more acceptable to the heir to the British throne. The result was an extension that politely mimics the main building, but has no connection to today.

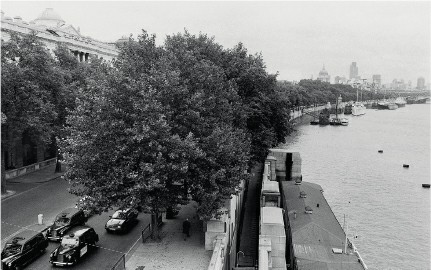

Trafalgar Square in the 1980s; a traffic-choked roundabout unworthy of a great city.

A sketch of the proposed pedestrianisation of the north of Trafalgar Square from London As It Could Be, the 1986 Royal Academy exhibition of work by Norman Foster, Jim Stirling and me. Fifteen years later, Norman’s detailed designs for the proposal would be realised.

London As It Could Be

I had another opportunity to push these ideas at the 1986 Royal Academy exhibition featuring Jim Stirling, Norman Foster and myself, curated by the brilliant Norman Rosenthal. The three of us were given free rein, but asked to showcase experimental thinking. Jim and Norman exhibited recently completed buildings – Jim’s Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart and Norman’s HSBC Building in Hong Kong – but I returned to the River Thames, and the strange absence where London’s heart should be. The Thames had always felt like a canyon or a barrier, rather than a connector. In the 1960s, all city life seemed to be on the North Bank; the South Bank just had the Royal Festival Hall, County Hall, and old wharf buildings. I visited Lambeth’s chief planner, responsible for this area, after I had left the AA, to ask whether we could convert some of the warehouses to homes and offices. He said that there might yet be a renaissance in port activity, so the riverside buildings should be preserved. Once more, the past was proposed as the blueprint for the future.

HSBC Main Building in Hong Kong, designed by Norman Foster and completed in 1985. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1986, alongside my London As It Could Be plans.

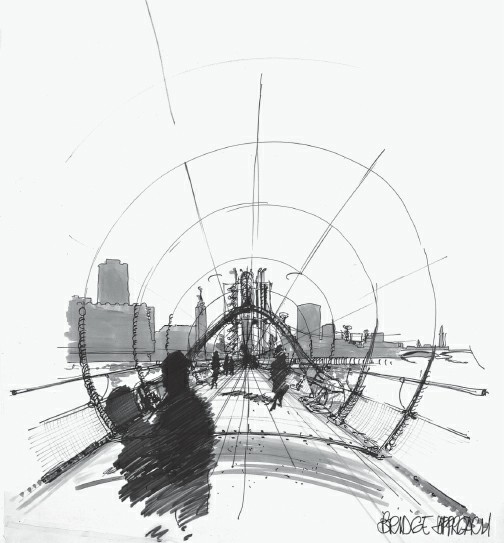

In 1986, we argued that the Thames should be transformed from a social and physical barrier – a canyon – to a connection. We proposed closing Charing Cross Station, and stopping all trains at Waterloo. The miserable Hungerford Railway Bridge, and its mean pedestrian walkways, would be knocked down and replaced with a beautiful new pedestrian bridge, with a shuttle train beneath to bring passengers from Waterloo station to the heart of Trafalgar Square. The bridge would be suspended from towers, with universities and cultural centres built into the pontoons, bringing people onto as well as across the river.

We would pedestrianise the north of Trafalgar Square (going further than we had dared to in our proposal for the National Gallery extension), and link it on a north–south axis to Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus. On the east–west axis, the Embankment would become a great south-facing riverside park, joining up a series of half-hidden gardens and squares, with walkways, restaurants and cafes, and space beneath for cars to run in tunnels alongside the District Line.

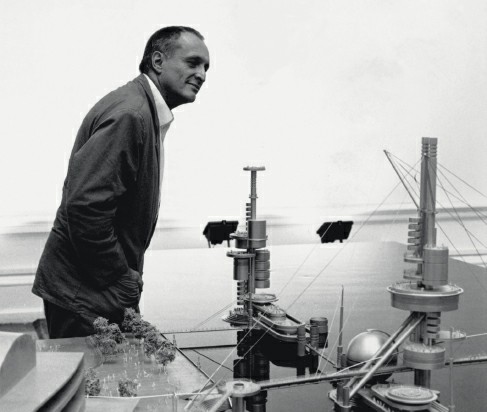

The models made for the exhibition by Laurie Abbott and Philip Gumuchdjian (with whom I later wrote Cities for a Small Planet) were beautiful, with a shallow pool of water representing the Thames. One evening, a mischievous Jim Stirling added some goldfish to the water, thinking they would add some amusement the next day. But he had not considered the water circulation system, which chewed up the goldfish and spat them out in pieces, making the water more horror film than fairground until it was drained and replaced (the incident attracted a formal complaint from the RSPCA).

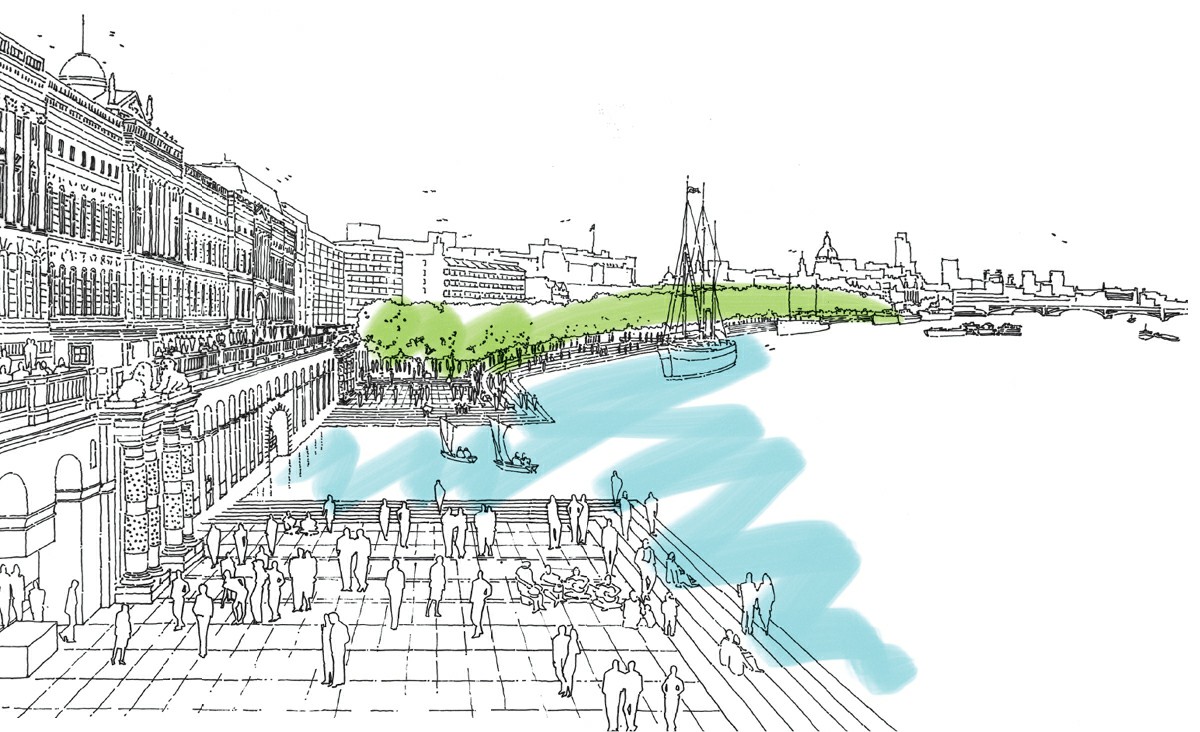

Our 1986 plans for a new bridge connecting Waterloo to the Embankment, flanked by floating islands with new restaurants, galleries and universities. Charing Cross Station would be closed, and a shuttle would bring visitors and commuters over to a North Bank reinvented as a linear park.

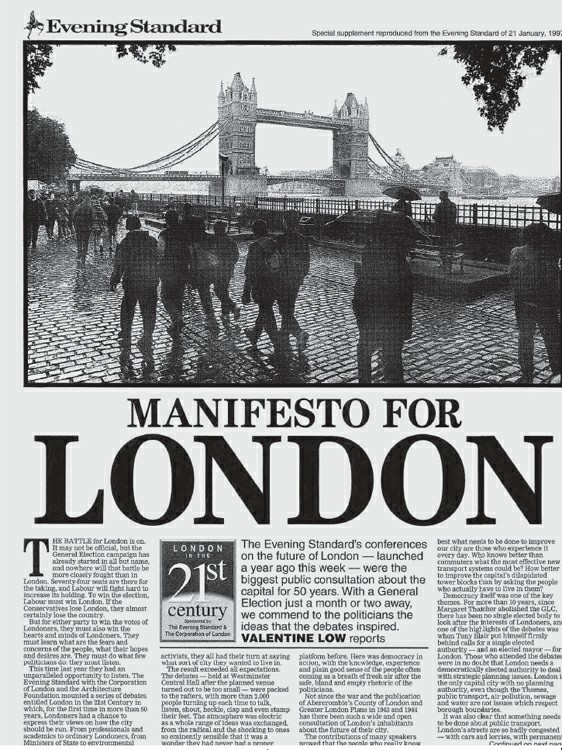

London As It Could Be was the most popular architectural show that the Royal Academy had ever held (until Inside Out in 2013), but it also illustrated how hard it was to make anything happen in London. We looked at the feasibility of building the new bridge, but discovered that 70 separate permissions were needed to build a bridge over the Thames, any one of whom could stop it. And London’s government was fragmenting too: the Greater London Council was in its last days, leaving the city without any strategic city-wide government from 1987 to 2000, by which time some of the ideas we were pushing would start to resurface.

Charing Cross Station is still there, and its rebuilding effectively blocked any plans for relocation, but the footbridge to the South Bank has been improved enormously, and the pedestrianisation of Trafalgar Square has been a huge success. In 1994, we won a competition to revitalise the South Bank Centre, and proposed a new ‘crystal palace’ – an undulating glass roof, oversailing the 1960s buildings but leaving the Royal Festival Hall rising above it. Alongside new pedestrian connections, this would have created a new mixed-use centre on the South Bank and a shop window for the arts, but the scheme ran into funding and community relations problems and was never completed.

Public Space – London Deserves Better

Many of London’s public spaces still let us down. Street life still fights for space with haphazard street furniture, badly parked cars and ugly paving half patched up with great gobs of tarmac. Many of what should be great spaces – like Leicester Square – have been turned into neon-lit outdoor malls. And our incredible heritage of garden squares is still mainly behind lock and key, inaccessible for the citizen and hardly used by the rich whose flats overlook them.

There are pinpricks of light. The Olympic Park in east London has been beautifully landscaped and is gradually finding its long-term function, giving a heart to an area that lacked good green space for many years. It is now home to London‘s youngest and fastest growing neighbourhoods, connected along revitalised canals to Islington, Camden and King’s Cross, where lively new (privately managed) public space has opened up what were once deserted rail lands or dangerous back alleys, for students, office workers and passers-by.

The Embankment reborn as a pedestrian space, from London As It Could Be (1986).

This terrace, in front of Somerset House, would reclaim the riverfront for pedestrians, with cars and other motor vehicles buried in tunnels beneath. Burying roads in tunnels seemed like a good solution at the time; today the focus is more on taking more surface space for cyclists and pedestrians, with congestion charging to reduce car use. Connecting the linear parks and public spaces along the Embankment is still unrealised.

The pedestrian bridge, with monorail running beneath, which we proposed to replace the railways running into Charing Cross.

The South Bank has finally been opened up, offering London’s greatest public spaces, enlivened by festivals and thronged by Londoners and visitors all the time. Dedicated cycle lanes have been put in place across the city, and many car-choked gyratories are being replaced by more civilised two-way streets, as at Aldwych, where my daughter-in-law Lucy Musgrave’s practice Publica have included this as part of their strategy for the area. All citizens should have the right to space. We are slowly moving forward, but there is so much left to do.

At the 1986 Royal Academy exhibition, alongside the models for our bridge and floating islands.

The London Evening Standard’s report on the debates, held in 1996, about London in the twenty-first century.