BY MORI

GAI

GAI GAI

GAION THE THIRTEENTH OF SEPTEMBER 1912, the day of Emperor Meiji’s funeral, General Nogi Maresuke killed himself by disembowelment, taking his wife, Shizuko, with him. He said in his testimonial: “In committing suicide to follow His Majesty in death, I am aware, with regret, that my crime in doing so is by no means negligible. However, since I lost my flag during the civil war of the tenth year of Meiji [1877], I have been looking for an appropriate opportunity to die, to no avail. Instead, to this day I have continued to be showered with imperial special favors and treated with exceptional compassion. While I have grown infirm, with few days left to be useful, this grave event has filled me with such remorse that I hereby have made this decision.”

The loss of a flag in a single battle was not the only cause of Nogi’s remorse – and his sense of indebtedness that he went unpunished. He had created vast casualties in his assaults on Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War, and he most likely knew that he was not relieved of his post, as recommended by the chief of the army general staff, because of Meiji’s intervention.

Nogi’s action, which some of the younger generation dismissed as “anachronistic,” affected a number of people. In the United States, for example, Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) wrote a poem entitled “Nogi” and published it in the second issue of the magazine she had just founded, Poetry:

Great soldier of the fighting clan,

Across Port Arthur’s frowning face of stone

You drew the battle sword of old Japan,

And struck the White Tsar from his Asian throne.

Your own proud way, O eastern star,

Grandly at last you followed. Out it leads

To that high heaven where all the heroes are,

Lovers of death for causes and for creeds.

Among the Japanese writers deeply shaken was Mori  gai (1862-1922).1 An army officer who studied military hygiene in Germany and quickly rose through the ranks to become surgeon general at age

forty-five,

gai (1862-1922).1 An army officer who studied military hygiene in Germany and quickly rose through the ranks to become surgeon general at age

forty-five,  gai was at the same time an influential man of letters actively engaged in introducing Western literary and philosophical

ideas to Japan. His friend Nogi’s suicide gave him pause. The depth of his feeling was obvious: On September 18, a mere six

days after Nogi’s death and on the very day he attended his funeral, he submitted to his publisher the first of his stories

drawing on Japan’s recent past. Entitled “Okitsu Yagoemon’s Testimonial,” it began: “I die by disembowelment this month, today.

This will strike some as abrupt, and they might say that I, Yagoemon, had become senile or that I had become deranged. But

that is not at all the case.” Yagoemon goes on to recount what had happened thirty years earlier.

gai was at the same time an influential man of letters actively engaged in introducing Western literary and philosophical

ideas to Japan. His friend Nogi’s suicide gave him pause. The depth of his feeling was obvious: On September 18, a mere six

days after Nogi’s death and on the very day he attended his funeral, he submitted to his publisher the first of his stories

drawing on Japan’s recent past. Entitled “Okitsu Yagoemon’s Testimonial,” it began: “I die by disembowelment this month, today.

This will strike some as abrupt, and they might say that I, Yagoemon, had become senile or that I had become deranged. But

that is not at all the case.” Yagoemon goes on to recount what had happened thirty years earlier.

gai published “The Abe Family,” translated below, the following January. It was his second “historical story.” In this recounting,

Hosokawa Tadatoshi (1586-1641) is a son of Tadaoki (Sansai, 1564-1645), a warlord famous for his accomplishments in court

protocol, traditional verse, and the art of drinking tea. Indeed, Okitsu Yagoemon’s killing of his colleague, for which he

atoned through disembowelment, occurred while the two men were on assignment to buy tea utensils for Tadaoki.

gai published “The Abe Family,” translated below, the following January. It was his second “historical story.” In this recounting,

Hosokawa Tadatoshi (1586-1641) is a son of Tadaoki (Sansai, 1564-1645), a warlord famous for his accomplishments in court

protocol, traditional verse, and the art of drinking tea. Indeed, Okitsu Yagoemon’s killing of his colleague, for which he

atoned through disembowelment, occurred while the two men were on assignment to buy tea utensils for Tadaoki.

In the spring of the eighteenth year of Kan’ei [1641], Hosokawa Tadatoshi, Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Minor Captain

of the Inner Palace Guards, Left Division, and Governor of Etch , was preparing to put himself at the center of a long procession

splendid enough for a daimyo of 540,000 koku and to leave the cherry blossoms of his fiefdom, Higo Province, which bloom earlier than elsewhere,

so that he might travel along with the spring, from south to north, on his biannual pilgrimage to the shogunate, in Edo,2 when unexpectedly he fell ill. The medicine prescribed by his doctor did not show any effect and his illness became graver

each day. An express messenger was dispatched to Edo with the news of the delay of his arrival. The third Tokugawa shogun,

Iemitsu, known as a distinguished ruler, expressed concern for Tadatoshi, who had done some important work in destroying Amakusa

Shir

, was preparing to put himself at the center of a long procession

splendid enough for a daimyo of 540,000 koku and to leave the cherry blossoms of his fiefdom, Higo Province, which bloom earlier than elsewhere,

so that he might travel along with the spring, from south to north, on his biannual pilgrimage to the shogunate, in Edo,2 when unexpectedly he fell ill. The medicine prescribed by his doctor did not show any effect and his illness became graver

each day. An express messenger was dispatched to Edo with the news of the delay of his arrival. The third Tokugawa shogun,

Iemitsu, known as a distinguished ruler, expressed concern for Tadatoshi, who had done some important work in destroying Amakusa

Shir Tokisada, leader of the Shimabara rebels.3 On the twentieth of the third month, he had Matsudaira, Governor of Izu, Abe, Governor of Bungo, and Abe, Governor of Tsushima,

compose an official letter of inquiry bearing their names and also had a Kyoto acupuncturist by the name of Isaku start for

Higo. On the twenty-second he had a samurai by the name of Soga Matazaemon dispatched as a shogunate messenger with the letter

signed by the three administrators.

Tokisada, leader of the Shimabara rebels.3 On the twentieth of the third month, he had Matsudaira, Governor of Izu, Abe, Governor of Bungo, and Abe, Governor of Tsushima,

compose an official letter of inquiry bearing their names and also had a Kyoto acupuncturist by the name of Isaku start for

Higo. On the twenty-second he had a samurai by the name of Soga Matazaemon dispatched as a shogunate messenger with the letter

signed by the three administrators.

Such measures from shogun to daimyo were unusual. But ever since the Shimabara rebels had been pacified three years earlier, in the spring of the fifteenth year of Kan’ei, the shogun had gone out of his way to extend courtesies to Tadatoshi on every possible occasion – giving him extra acreage for his Edo mansion, presenting him with cranes for his falconry, and so forth. At the news of Tadatoshi’s serious illness, the shogun naturally tried to convey as much concern as precedent allowed.

Yet, even before the shogun began making these arrangements, Tadatoshi’s illness, in his Flower Field Mansion in Kumamoto,

had quickened its pace, and on the seventeenth of the third month, about four in the afternoon, he died, at the age of fifty-six.

His wife was a daughter of Ogasawara Hidemasa, Fifth Rank in the Ministry of Military Affairs, whom the shogun had adopted

and married to Tadatoshi. Forty-five that year, she was commonly called Lady Osen. Tadatoshi’s first son, Rokumaru, had performed

his manhood rites six years before, when he was endowed by the shogun with part of his name, mitsu, and changed his name to Mitsusada; at the same time he was appointed Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Chamberlain, and Governor

of Higo. He was now seventeen. At the time of Tadatoshi’s death he was in Hamamatsu, T t

t mi Province, on his way back from

his biannual pilgrimage, but at the news of his father’s death, he returned to Edo at once. Later he changed his name to Mitsuhisa.

mi Province, on his way back from

his biannual pilgrimage, but at the news of his father’s death, he returned to Edo at once. Later he changed his name to Mitsuhisa.

Tadatoshi’s second son, Tsuruchiyo, had been placed in the Taish temple, on Mt. Tatta, since childhood. He had become a disciple

of Priest Taien from Kyoto’s My

temple, on Mt. Tatta, since childhood. He had become a disciple

of Priest Taien from Kyoto’s My shin temple, and was now called S

shin temple, and was now called S gen. Tadatoshi’s third son, Matsunosuke, was being brought

up by the Nagaoka, a family related to the Hosokawa from the old days. Tadatoshi’s fourth son, Katsuchiyo, had been adopted

by his retainer, Nanj

gen. Tadatoshi’s third son, Matsunosuke, was being brought

up by the Nagaoka, a family related to the Hosokawa from the old days. Tadatoshi’s fourth son, Katsuchiyo, had been adopted

by his retainer, Nanj Daizen.

Daizen.

Tadatoshi had two daughters. The elder one, Princess Fuji, was the wife of Matsudaira Tadahiro, Governor of Su . Princess

Take, the younger one, was later to be married to Ariyoshi Tanomo Hidenaga.

. Princess

Take, the younger one, was later to be married to Ariyoshi Tanomo Hidenaga.

Tadatoshi himself was Hosokawa Sansai’s third son, and had three younger brothers: the fourth son, Tatsutaka, Fifth Rank in

the Ministry of Central Affairs; the fifth son, Okitaka, of the Ministry of Justice; and the sixth son, Nagaoka Yoriyuki,

of the Ministry of Ceremonial. His younger sisters were Princess Tara, married to Inaba Kazumichi, and Princess Man, married

to Middle Counselor Ka-rasumaru Mitsutaka. Princess Man’s daughter, Princess Nene, would later become the wife of Mitsuhisa,

Tadatoshi’s first son. Of his older siblings, the two elder brothers had assumed the name of Nagaoka, and one of his two older

sisters was married to Maeno, the other to Nagaoka. His retired father, Sansai S ry

ry , was still alive, at seventy-nine. Of

these people, some, like Mitsusada, were in Edo, and some in Kyoto and other distant provinces when Tadatoshi died. They grieved

at the news that reached them belatedly, but their grief was not as immediate and acute as that of the people who were in

his mansion in Kumamoto at his death. Two men, Musushima Sh

, was still alive, at seventy-nine. Of

these people, some, like Mitsusada, were in Edo, and some in Kyoto and other distant provinces when Tadatoshi died. They grieved

at the news that reached them belatedly, but their grief was not as immediate and acute as that of the people who were in

his mansion in Kumamoto at his death. Two men, Musushima Sh kichi and Tsuda Rokuzaemon, departed for Edo as formal messengers.

kichi and Tsuda Rokuzaemon, departed for Edo as formal messengers.

On the twenty-fourth of the third month the Rite of the Seventh Day was performed. On the twenty-eighth of the fourth month

the floor boards of the living room of Tadatoshi’s mansion were removed and his coffin was dug out of the ground below, where

it had been laid, and, following directions from Edo, the corpse was cremated at Sh ’un-in, in Kasuga Village, Akita County,

before being buried on the hill outside K

’un-in, in Kasuga Village, Akita County,

before being buried on the hill outside K rai Gate. In the winter of the following year, below this mausoleum, a temple called Gokokuzan My

rai Gate. In the winter of the following year, below this mausoleum, a temple called Gokokuzan My ge was

built, and Priest Keishitsu, who had studied with Priest Takuan, came from T

ge was

built, and Priest Keishitsu, who had studied with Priest Takuan, came from T kai Temple, in Shinagawa, Edo, to become the

resident chief priest. Later, when Keishitsu retired to the Rinry

kai Temple, in Shinagawa, Edo, to become the

resident chief priest. Later, when Keishitsu retired to the Rinry Hut within the temple compounds, Tadatoshi’s second son,

S

Hut within the temple compounds, Tadatoshi’s second son,

S gen, would inherit the temple, calling himself Priest Tengan. Tadatoshi’s posthumous Buddhist name was My

gen, would inherit the temple, calling himself Priest Tengan. Tadatoshi’s posthumous Buddhist name was My ge-in-den Taiun

S

ge-in-den Taiun

S go the Great Layman.

go the Great Layman.

Tadatoshi’s cremation at Sh ’un-in was faithful to his will. Once when he was out moor-hen hunting, he had stopped at Sh

’un-in was faithful to his will. Once when he was out moor-hen hunting, he had stopped at Sh ’un-in

to have some tea. There he noticed that the beard had grown under his chin, and asked the chief priest if he had a razor.

The priest had a basin of water brought and offered it to him with a razor. While having a page shave his beard, Tadatoshi,

in a good mood, asked the priest, “I guess you have shaved lots of dead men’s heads with this razor, haven’t you?” The priest

didn’t know how to respond, utterly lost as he was. After this Tadatoshi became good friends with him and decided that the

temple would be the place of his cremation.

’un-in

to have some tea. There he noticed that the beard had grown under his chin, and asked the chief priest if he had a razor.

The priest had a basin of water brought and offered it to him with a razor. While having a page shave his beard, Tadatoshi,

in a good mood, asked the priest, “I guess you have shaved lots of dead men’s heads with this razor, haven’t you?” The priest

didn’t know how to respond, utterly lost as he was. After this Tadatoshi became good friends with him and decided that the

temple would be the place of his cremation.

It happened in the middle of the cremation. Some of the retainers guarding the coffin shouted, “Look, our lord’s hawks!” In the dull-blue patch of the sky blurred by the tall cedar trees in the temple compound, and above the cherry leaves hanging like an umbrella over the round frame of the well, two hawks were flying in circles. While people looked on in puzzlement, the hawks, so close to each other that one’s beak almost touched the other’s tail, swooped down and plunged into the well beneath the cherry tree. Two men broke out of the group of several people arguing something at the temple gate, ran to the well, and, hands on the stone well-curb, looked in. By then the hawks had sunk deep to the bottom, and the surface of the water fringed with fern was glistening like a mirror as before. The two men were Tadatoshi’s falconers. The two hawks that had plunged into the well and died were Ariake and Akashi, hawks Tadatoshi had particularly loved. When this became known, people were heard to say, “So, even our lord’s hawks have followed him in death!”

Such a response was to be expected: Between the day of Tadatoshi’s passage into the other world and two days before his cremation,

more than ten retainers had killed themselves to follow him in death. Indeed, two days before the cremation, as many as eight

men had disemboweled themselves at once, and the day before yet another had done the same. As a result, there were no retainers

who were not thinking of death. How the falconers had been so careless as to let the hawks loose and why the hawks had plunged into the

well as if chasing an invisible prey wasn’t known, but no one even bothered to speculate. That they were the hawks Tadatoshi

had loved, and that they died on the very day of his cremation, in the well of Sh ’un-in where the cremation was being performed,

was enough for the people to conclude that the hawks deliberately followed their lord in death. There was no room in their

minds to doubt this judgment and try to find out some other cause.

’un-in where the cremation was being performed,

was enough for the people to conclude that the hawks deliberately followed their lord in death. There was no room in their

minds to doubt this judgment and try to find out some other cause.

The Rite of the Forty-ninth Day was performed on the fifth of the fifth month. The priests who had performed the various rites

up to that time included S gen and those from Kisei-d

gen and those from Kisei-d , Konry

, Konry -d

-d , Tenju-an, Ch

, Tenju-an, Ch sh

sh -in, and Fuji-an. Now the sixth of the

fifth month came around, but still deaths by disembowelment occurred. Not to mention those who intended to follow Tadatoshi

in death, their parents, siblings, wives, children, and even those unrelated to them thought only of death, while absent-mindedly

welcoming the acupuncturist from Kyoto and formal messengers from Edo. They did not collect iris stalks to adorn their eaves

for the annual celebration of Boys’ Day. Even those who had newborn sons raised no streamers and kept quiet, as if trying

to forget that sons had been born to them.

-in, and Fuji-an. Now the sixth of the

fifth month came around, but still deaths by disembowelment occurred. Not to mention those who intended to follow Tadatoshi

in death, their parents, siblings, wives, children, and even those unrelated to them thought only of death, while absent-mindedly

welcoming the acupuncturist from Kyoto and formal messengers from Edo. They did not collect iris stalks to adorn their eaves

for the annual celebration of Boys’ Day. Even those who had newborn sons raised no streamers and kept quiet, as if trying

to forget that sons had been born to them.

When and how it came about is not known, but an unstated rule governed a retainer’s following his lord in death by disembowelment. The retainer’s profound respect and love of his lord did not automatically entitle him to perform the act. Just as permission was needed for accompanying the lord on the biannual pilgrimage to Edo in peacetime, or to the battlefield in wartime, so was it absolutely necessary to accompany him across the River of Death. A death without permission was “a dog’s death.” And a samurai would not die a dog’s death because good reputation was of the utmost value to him. To plunge into the enemy turf and get killed in battle would be praiseworthy, but it would not win a man any honor if he ignored the order, sneaked out to accomplish some exploits, and was killed. That would be a dog’s death; in the same way, killing oneself by disembowelment without permission would serve no purpose.

At times, a retainer disemboweling himself to follow his lord in death without permission might not be thought to have died a dog’s death. Such a case was possible where a tacit agreement had formed between the lord and the retainer he had especially favored – where the absence of permission did not mean anything. The teachings of the Great Vehicle were expounded after the Buddha entered nirvana even though the Buddha had not given permission to do so. But this was permissible, it is said, because the Buddha, omniscient of the past, the present, and the future, had allowed that such teachings would ensue. Some people could die for their lords without permission in the same way that the teachings of the Great Vehicle could be preached as if from the Buddha’s own mouth.

How, then, was permission obtained? Among those who had already died for Tadatoshi, Nait Ch

Ch j

j r

r Mototsugu provides a good

example. Ch

Mototsugu provides a good

example. Ch j

j r

r had worked for Tadatoshi in his study and won his special favor. After Tadatoshi fell ill, he never left

his side. When Tadatoshi realized he would never recover, he told Ch

had worked for Tadatoshi in his study and won his special favor. After Tadatoshi fell ill, he never left

his side. When Tadatoshi realized he would never recover, he told Ch j

j r

r that if his death became imminent, he, Ch

that if his death became imminent, he, Ch j

j r

r ,

should hang in the alcove near his pillow the scroll with two large characters, Fu-Ji, “Incomparable.”4 On the seventeenth of the third month, when his condition gradually deteriorated, Tadatoshi said the time had come to hang

the scroll. Ch

,

should hang in the alcove near his pillow the scroll with two large characters, Fu-Ji, “Incomparable.”4 On the seventeenth of the third month, when his condition gradually deteriorated, Tadatoshi said the time had come to hang

the scroll. Ch j

j r

r did as he was told. Tadatoshi took one look at the scroll and closed his eyes for a while in meditation.

Then he said his legs felt dull. Ch

did as he was told. Tadatoshi took one look at the scroll and closed his eyes for a while in meditation.

Then he said his legs felt dull. Ch j

j r

r carefully pulled open the skirts of Tadatoshi’s bedclothes and, as he massaged his

legs, looked Tadatoshi directly in the eye. Tadatoshi returned the look.

carefully pulled open the skirts of Tadatoshi’s bedclothes and, as he massaged his

legs, looked Tadatoshi directly in the eye. Tadatoshi returned the look.

“Sir, may I make a request?”

“What is it?”

“Your condition seems serious indeed, and I pray that you recover as soon as possible with the protection of the gods and the Buddha, as well as with the remarkable effect of good medicine. However, one must prepare for the worst. If the worst should happen, would you please kindly command me to accompany you?”

Ch j

j r

r gently held up Tadatoshi’s foot and put his forehead on it. His eyes were full of tears.

gently held up Tadatoshi’s foot and put his forehead on it. His eyes were full of tears.

“No, I will not do any such thing,” said Tadatoshi and, though looking at Ch j

j r

r in the eye till then, he twisted his body

to turn away.

in the eye till then, he twisted his body

to turn away.

“Please, do not say that, sir.” Ch j

j r

r held up his lord’s foot again.

held up his lord’s foot again.

“No, no.” Tadatoshi kept his back turned to him. One of the retainers sitting in attendance in the same room said, “You’re

too young to be that impudent. Restrain yourself.” Ch j

j r

r was just seventeen years old that year.

was just seventeen years old that year.

“Please.” Ch j

j r

r said as if choking, and kept his forehead on his lord’s foot, which he held up for the third time and would

not let go.

said as if choking, and kept his forehead on his lord’s foot, which he held up for the third time and would

not let go.

“You are stubborn,” said Tadatoshi as if angered. But as he said this, he nodded twice.

“Sir!” Ch j

j r

r said and, with Tadatoshi’s foot held in his hands, bowed down low near the bed and remained still. At that

moment he felt himself fill with a sense of relaxation and calm as if he had passed some very difficult spot and reached the

place he had to get to; other than that, nothing came to his consciousness, and he was even unaware of the tears he shed on

the mat made in Bingo Province.

said and, with Tadatoshi’s foot held in his hands, bowed down low near the bed and remained still. At that

moment he felt himself fill with a sense of relaxation and calm as if he had passed some very difficult spot and reached the

place he had to get to; other than that, nothing came to his consciousness, and he was even unaware of the tears he shed on

the mat made in Bingo Province.

Ch j

j r

r was still quite young and had done nothing remarkable, but Tadatoshi had given him constant attention and kept him

close. The young man liked drinking, and once committed a blunder for which another might have received a reprimand. But Tadatoshi

said, “Not Ch

was still quite young and had done nothing remarkable, but Tadatoshi had given him constant attention and kept him

close. The young man liked drinking, and once committed a blunder for which another might have received a reprimand. But Tadatoshi

said, “Not Ch j

j r

r but the sake did it,” and dismissed it with a smile. Because of this Ch

but the sake did it,” and dismissed it with a smile. Because of this Ch j

j r

r came to believe that he had

to return this generosity and make up for his mistake. After Tadatoshi’s illness became serious, this belief became the firm

conviction that the only way to convey his apologies and compensate for the error was to follow his lord in death.

came to believe that he had

to return this generosity and make up for his mistake. After Tadatoshi’s illness became serious, this belief became the firm

conviction that the only way to convey his apologies and compensate for the error was to follow his lord in death.

If you stepped into this young man’s mind to look closely at it, though, you’d find that side by side with the thought that he would, by his own will, follow his lord in death, another thought existed with equal force: that he was obliged to die because other people expected him to do so – a sense of dependency on others for moving in the direction of death. In other words, he was worried that if he did not die, he would be subjected to horrible humiliation. This was his weakness, but he was not in the least afraid of death. And so nothing had interfered with his wish to ask his lord for permission to die, with that determination dominating his entire mind.

After a while Ch j

j r

r felt Tadatoshi tense his foot that he held with both hands and stretch it a little. He thought his lord

felt it had become numb again, and began slowly to massage it as he had done at the outset. Then his old mother and his wife

came to his mind. He reminded himself that the relatives of those who commit suicide to follow their lord receive preferential

treatment from the lord’s house. He thought that he now had placed his family in a safe position, that he could die peacefully.

With the thought, his face brightened.

felt Tadatoshi tense his foot that he held with both hands and stretch it a little. He thought his lord

felt it had become numb again, and began slowly to massage it as he had done at the outset. Then his old mother and his wife

came to his mind. He reminded himself that the relatives of those who commit suicide to follow their lord receive preferential

treatment from the lord’s house. He thought that he now had placed his family in a safe position, that he could die peacefully.

With the thought, his face brightened.

On the morning of the seventeenth of the fourth month, Ch j

j r

r put on his formal attire, came to his mother, told her of his

decision to follow his lord, and said some words of farewell. His mother showed no surprise. Though she had not said it to

him, she had long known that this was the day for her son to disembowel himself. If he had told her that he would not do so,

she would have been alarmed.

put on his formal attire, came to his mother, told her of his

decision to follow his lord, and said some words of farewell. His mother showed no surprise. Though she had not said it to

him, she had long known that this was the day for her son to disembowel himself. If he had told her that he would not do so,

she would have been alarmed.

His mother called in his newlywed bride from the kitchen and asked if the preparations were made. The wife rose to her feet

at once, and returned with a tray of sake, which she’d had ready since earlier that morning. Like the mother she, too, had

long known that this was the day for her husband to disembowel himself. She had set her hair neatly and wore one of her better

house kimonos. Both mother and wife appeared the same, looking formal and solemn, but the corners of the wife’s eyes were

red, revealing that she had wept in the kitchen. When the tray was set before him, Ch j

j r

r called in his brother, Saheiji.

called in his brother, Saheiji.

The four drank from one cup by turns, silently. When the cup had made a round, the mother said, “Ch j

j r

r , I know you like

drinking. Why don’t you drink a little more than usual today?”

, I know you like

drinking. Why don’t you drink a little more than usual today?”

“Right, mother,” Ch j

j r

r said, and he drank one cup after another with a smile on his face, obviously feeling good.

said, and he drank one cup after another with a smile on his face, obviously feeling good.

After a while, he said to his mother, “I have enjoyed the sake, and feel a little drunk. The sake has worked better than usual, perhaps because I’ve been worried about various matters for the last several days. May I excuse myself and rest a while?”

With that Ch j

j r

r rose to his feet and entered the living room, where he lay down in the middle of the room and soon began

to snore. When his wife, who had followed him quietly, put a pillow under his head, he moaned and turned, but kept snoring.

His wife gazed at his face for some time; then abruptly she rose and left the room. She knew she should not cry in his presence.

rose to his feet and entered the living room, where he lay down in the middle of the room and soon began

to snore. When his wife, who had followed him quietly, put a pillow under his head, he moaned and turned, but kept snoring.

His wife gazed at his face for some time; then abruptly she rose and left the room. She knew she should not cry in his presence.

The entire household was quiet. Just as mother and wife had known the master’s decision before being told, so had his retainers and handmaid. Nothing like laughter was heard either from the stable or the kitchen.

The mother stayed in her room, the wife in hers, and the brother in his, each in deep thought. The master snored away in the living room. In the window of the living room, which was left wide open, a bundle of shinobu fern, with a wind chime attached to it, hung under the eaves. The wind chime faintly tinkled from time to time, as if to remind itself of its job. Beneath it was a washbasin, a tall piece of rock with a hole dug in the top and filled with water. Perched on the wooden dipper placed across the basin face down, was a blue darner, wings drooping mountain-shape, motionless.

Two hours went by, and another two hours. Now it was past noon. The wife had told the handmaid to get lunch ready, but she was not sure her mother-in-law wanted it. She hesitated to go to her to ask because she was afraid that if she asked her about a meal, her mother-in-law might suspect that she was the only one who thought of eating at such a time.

At that juncture Seki Koheiji came, a man Ch j

j r

r had asked to be his second. The mother called the wife. The wife bowed to

her and, her hands on the floor, remained silent to see what her wishes might be.

had asked to be his second. The mother called the wife. The wife bowed to

her and, her hands on the floor, remained silent to see what her wishes might be.

“Ch j

j r

r said he’d rest awhile,” said the mother, “but it’s some time since he excused himself. Here is Mr. Seki. I would

think it’s time to wake him.”

said he’d rest awhile,” said the mother, “but it’s some time since he excused himself. Here is Mr. Seki. I would

think it’s time to wake him.”

“Yes, you’re right. It mustn’t be done too late,” said the wife. She rose to her feet at once and left to wake her husband.

In the living room, the wife looked at her husband’s face again, just as she had when she brought in the pillow. The thought that she was going to wake him to death made it difficult for her to speak for a while.

Though in profound sleep, he must have felt the bright light coming in the window; his back was turned toward the window, his face toward her.

“Come, my dear,” the wife called out.

Ch j

j r

r did not wake.

did not wake.

The wife edged up to him on her knees and touched his shoulder that rose high. Ch j

j r

r yawned, stretched his elbows, opened

his eyes, and sat up.

yawned, stretched his elbows, opened

his eyes, and sat up.

“You have rested very well,” said his wife. “I woke you because Mother said it was getting late. Mr. Seki has come too.”

“I see. It must be noon now. I thought I might take a little rest, but I was both drunk and tired and wasn’t aware how time

was passing. I think it’s time to take rice with tea and go to T k

k -in. Tell Mother I’m ready.”

-in. Tell Mother I’m ready.”

On a life-or-death occasion a samurai did not eat his fill. But he would not set out to do something important with an empty

stomach, either. Ch j

j r

r had indeed intended to take a nap, but ended up having a much longer, though pleasant, sleep than he had expected,

and found out it was already noon. That’s why he offered to have a meal. So, though it was more a matter of formality, the

four members of the family sat at table as they did at ordinary times, and had lunch. Then Ch

had indeed intended to take a nap, but ended up having a much longer, though pleasant, sleep than he had expected,

and found out it was already noon. That’s why he offered to have a meal. So, though it was more a matter of formality, the

four members of the family sat at table as they did at ordinary times, and had lunch. Then Ch j

j r

r prepared himself calmly

and went with Seki to his family temple, T

prepared himself calmly

and went with Seki to his family temple, T k

k -in, to disembowel himself.

-in, to disembowel himself.

Around the time Ch j

j r

r held Tadatoshi’s foot in his hand to ask for his permission, some others among Tadatoshi’s retainers

who had enjoyed his special favors asked, each in his own fashion, permission to follow him in death, and those who did so,

including Ch

held Tadatoshi’s foot in his hand to ask for his permission, some others among Tadatoshi’s retainers

who had enjoyed his special favors asked, each in his own fashion, permission to follow him in death, and those who did so,

including Ch j

j r

r , numbered eighteen. All of them were samurai Tadatoshi trusted deeply. Therefore, Tadatoshi wished sincerely

to leave these men behind him for the protection of his son, Mitsuhisa. Also, he was fully aware that it was cruel to have

them die with him. But he gave each of them the word, “Granted,” while feeling great pain in doing so, because the circumstances

did not allow him to do otherwise.

, numbered eighteen. All of them were samurai Tadatoshi trusted deeply. Therefore, Tadatoshi wished sincerely

to leave these men behind him for the protection of his son, Mitsuhisa. Also, he was fully aware that it was cruel to have

them die with him. But he gave each of them the word, “Granted,” while feeling great pain in doing so, because the circumstances

did not allow him to do otherwise.

Tadatoshi believed that the men he kept in such close employment would be glad to offer their lives for him. He also knew that killing themselves would not be a painful thing for them. If, however, he did not give them permission to follow him in death but made them survive him, what would happen? The other retainers would show no restraint in saying that these men had not died when they should have, that they had no sense of obligation, that they were cowards. If that were all, they might put up with it and wait for the chance to offer their lives to Mitsuhisa. But suppose someone went on to say that he, now the deceased lord, had kept such men in his employment without realizing that they had no sense of obligation and were in fact cowards, that would be more than they could bear – there would be no end to their regrets. When he thought this far, Tadatoshi could not but give his permission. That was why, even while feeling worse about it than about his own illness, he said, “Granted.”

When the number of the retainers to whom he gave permission reached eighteen, Tadatoshi, who had lived through times of peace and disturbances for more than fifty years and was acquainted thoroughly with every shade of human affairs, thought in his illness and pain about his own death and the deaths of the eighteen samurai. No living thing can avoid death. Right next to an old tree that withers and dies, young trees sprout green leaves and flourish. From the viewpoint of the young men surrounding his first son, Mitsuhisa, the old men whom he, Tadatoshi, had around him were no longer needed. They could even be obstacles. He wished they would survive him and provide Mitsuhisa with the kind of service they had provided him, but there were now enough new people who could do the same for his son, and they might be waiting for their turn impatiently. Some of his own appointees had probably garnered hatred–or at least, had become targets of jealousy–in carrying out their duties for such a long time. Seen this way, telling them to live longer might not be an entirely sagacious idea. Granting them permission to die may have been an act of mercy. So thinking, Tadatoshi felt some consolation.

The eighteen men who asked for and were granted permission to follow Tadatoshi in death were Teramoto Hachizaemon Naotsugu,

tsuka Kih

tsuka Kih Tanetsugu, Nait

Tanetsugu, Nait Ch

Ch j

j r

r Mototsugu,

Mototsugu,  ta Koj

ta Koj r

r Masanobu, Harada J

Masanobu, Harada J jir

jir Yukinao, Munakata Kah

Yukinao, Munakata Kah Kagesada, Munakata

Kichiday

Kagesada, Munakata

Kichiday Kageyoshi, Hashitani Ichiz

Kageyoshi, Hashitani Ichiz Shigetsugu, Ihara J

Shigetsugu, Ihara J zabur

zabur Yoshimasa, Tanaka Itoku, Honj

Yoshimasa, Tanaka Itoku, Honj Kisuke Shigemasa, It

Kisuke Shigemasa, It Tazaemon

Masataka, Migita Inaba Muneyasu, Noda Kih

Tazaemon

Masataka, Migita Inaba Muneyasu, Noda Kih Shigetsuna, Tsuzaki Gosuke Nagasue, Kobayashi Riemon Yukihide, Hayashi Yozaemon

Masasada, and Miyanaga Katsuzaemon Munesuke.

Shigetsuna, Tsuzaki Gosuke Nagasue, Kobayashi Riemon Yukihide, Hayashi Yozaemon

Masasada, and Miyanaga Katsuzaemon Munesuke.

Teramoto’s direct ancestor was a man by the name of Teramoto Tar , a resident of Teramoto, in the Province of Owari. Tar

, a resident of Teramoto, in the Province of Owari. Tar ’s

son, Naizen’nosh

’s

son, Naizen’nosh , served the Imagawa family. Naizen’nosh

, served the Imagawa family. Naizen’nosh ’s son was Sah

’s son was Sah , Sah

, Sah ’s son was Uemon’nosuke, and Uemon’nosuke’s

son was Yozaemon. In the Korean conquest5 Yozaemon served Kat

’s son was Uemon’nosuke, and Uemon’nosuke’s

son was Yozaemon. In the Korean conquest5 Yozaemon served Kat Yoshiaki’s army and did some distinguished work. Yozaemon’s son was Hachizaemon and during the siege

of Osaka Castle once worked under Got

Yoshiaki’s army and did some distinguished work. Yozaemon’s son was Hachizaemon and during the siege

of Osaka Castle once worked under Got Mototsugu.6 After the Hosokawa family retained Hachizaemon, he was given 1,000 koku and was made head of a fifty-gun regiment. He disemboweled

himself at the An’y

Mototsugu.6 After the Hosokawa family retained Hachizaemon, he was given 1,000 koku and was made head of a fifty-gun regiment. He disemboweled

himself at the An’y temple on the twenty-ninth of the fourth month. He was fifty-three years old. Fujimoto Izaemon seconded

him.

temple on the twenty-ninth of the fourth month. He was fifty-three years old. Fujimoto Izaemon seconded

him.  tsuka was a superintendent of police who received 150 koku. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month. Ikeda Yazaemon seconded him.

tsuka was a superintendent of police who received 150 koku. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month. Ikeda Yazaemon seconded him.

I have already talked about Nait .

.

Ota’s grandfather, Denzaemon, served Kat Kiyomasa. When Tadahiro7 was stripped of his fief, Denzaemon and his son, Genzaemon, became masterless drifters. Kojur

Kiyomasa. When Tadahiro7 was stripped of his fief, Denzaemon and his son, Genzaemon, became masterless drifters. Kojur was the second son of Genzaemon

and had been retained as a page by Tadatoshi. He received 150 koku. The first man to follow Tadatoshi in death, he disemboweled

himself on the seventeenth of the third month, at the Kasuga temple. He was eighteen. Moji Genb

was the second son of Genzaemon

and had been retained as a page by Tadatoshi. He received 150 koku. The first man to follow Tadatoshi in death, he disemboweled

himself on the seventeenth of the third month, at the Kasuga temple. He was eighteen. Moji Genb seconded him. Harada, a recipient

of 150 koku, served Tadatoshi at his side. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month. Kamada Genday

seconded him. Harada, a recipient

of 150 koku, served Tadatoshi at his side. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month. Kamada Genday seconded him.

seconded him.

The Munakata brothers, Kah and Kichiday

and Kichiday were the descendants of Middle Counselor Munakata Ujisada and their service with

the Hosokawa began with their father, Seib

were the descendants of Middle Counselor Munakata Ujisada and their service with

the Hosokawa began with their father, Seib Kagenobu. Both brothers received 200 koku. On the second of the fifth month the

older brother disemboweled himself at Ryuch

Kagenobu. Both brothers received 200 koku. On the second of the fifth month the

older brother disemboweled himself at Ryuch -in, and the younger brother at the Rensh

-in, and the younger brother at the Rensh temple. The older brother’s second

was Takata J

temple. The older brother’s second

was Takata J be, the younger brother’s Murakami Ichiemon. Hashitani was from the Province of Izumo and was a distant offspring

of the Amako clan. Retained by Tadatoshi when fourteen, he, a recipient of 100 koku, waited on Tadatoshi as a poison taster.

When his illness became serious, Tadatoshi at times laid his head on Hashitani’s lap and slept. On the twenty-sixth of the

fourth month he disemboweled himself at the Seigan temple. As he was about to slash his abdomen, there was a faint sound of

the hour drum at the castle. He told one of his retainers accompanying him to go out and ascertain the time. Upon his return,

the man said, “I heard the last four, but I’m not sure what the total number of drumbeats was.” This made Hashitani and others

smile. Hashitani said, “Thanks for making me laugh in my last moments,” gave the retainer the formal outer garment he wore,

and disemboweled himself. Yoshimura Jintay

be, the younger brother’s Murakami Ichiemon. Hashitani was from the Province of Izumo and was a distant offspring

of the Amako clan. Retained by Tadatoshi when fourteen, he, a recipient of 100 koku, waited on Tadatoshi as a poison taster.

When his illness became serious, Tadatoshi at times laid his head on Hashitani’s lap and slept. On the twenty-sixth of the

fourth month he disemboweled himself at the Seigan temple. As he was about to slash his abdomen, there was a faint sound of

the hour drum at the castle. He told one of his retainers accompanying him to go out and ascertain the time. Upon his return,

the man said, “I heard the last four, but I’m not sure what the total number of drumbeats was.” This made Hashitani and others

smile. Hashitani said, “Thanks for making me laugh in my last moments,” gave the retainer the formal outer garment he wore,

and disemboweled himself. Yoshimura Jintay seconded him.

seconded him.

Ihara received ten koku and an allowance for three retainers. At the time of his disembowelment Hayashi Sah , a retainer of

Abe Yaichiemon’s,8 seconded him. Tanaka was a grandson of Okiku, who has left us Okiku’s Story,9 and was a boyhood friend of Tadatoshi’s since both went to study on Mt. Atago. Once during that period of study he quietly

dissuaded the young Tadatoshi from entering the priesthood. Later a recipient of 200 koku, he served Tadatoshi as his personal

attendant. He was quite good at mathematics, and was useful with that skill. As an old man he was allowed to sit cross-legged

with his hood on in Tadatoshi’s presence. He asked Mitsuhisa to permit him to follow Tadatoshi in death, but the permission

was not granted. On the nineteenth of the sixth month, he stabbed his abdomen with a short sword, then sent a petition to

Mitsuhisa, who finally gave him permission. Kat

, a retainer of

Abe Yaichiemon’s,8 seconded him. Tanaka was a grandson of Okiku, who has left us Okiku’s Story,9 and was a boyhood friend of Tadatoshi’s since both went to study on Mt. Atago. Once during that period of study he quietly

dissuaded the young Tadatoshi from entering the priesthood. Later a recipient of 200 koku, he served Tadatoshi as his personal

attendant. He was quite good at mathematics, and was useful with that skill. As an old man he was allowed to sit cross-legged

with his hood on in Tadatoshi’s presence. He asked Mitsuhisa to permit him to follow Tadatoshi in death, but the permission

was not granted. On the nineteenth of the sixth month, he stabbed his abdomen with a short sword, then sent a petition to

Mitsuhisa, who finally gave him permission. Kat Yasuday

Yasuday seconded him.

seconded him.

Honj was from Tango Province. While a masterless drifter, he was retained as a servant by Honj

was from Tango Province. While a masterless drifter, he was retained as a servant by Honj Ky

Ky emon, a room attendant

for Lord Sansai. After he arrested a burglar at Nakatsu, he was given fifteen koku and an allowance for five retainers. It

was then that he assumed the name of Honj

emon, a room attendant

for Lord Sansai. After he arrested a burglar at Nakatsu, he was given fifteen koku and an allowance for five retainers. It

was then that he assumed the name of Honj . He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month.

. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth month.

It served as a senior accountant who received his stipend in rice. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth

month. His second was Kawakita Hachisuke. Migita became master-less while with the

served as a senior accountant who received his stipend in rice. He disemboweled himself on the twenty-sixth of the fourth

month. His second was Kawakita Hachisuke. Migita became master-less while with the  tomo family. Tadatoshi retained him with

land worth 100 koku. On the twenty-seventh of the fourth month he disemboweled himself in his own house. He was sixty-four.

Tahara Kanb

tomo family. Tadatoshi retained him with

land worth 100 koku. On the twenty-seventh of the fourth month he disemboweled himself in his own house. He was sixty-four.

Tahara Kanb , a retainer of Matsuno Uky

, a retainer of Matsuno Uky ’s, seconded him. Noda was a son of Noda Mino, the chief administrator of the Amakusa

family, and was retained with a stipend in rice. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled himself at the Genkaku

temple. His second was Era Han’emon. About Tsuzaki Gosuke I will write later.

’s, seconded him. Noda was a son of Noda Mino, the chief administrator of the Amakusa

family, and was retained with a stipend in rice. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled himself at the Genkaku

temple. His second was Era Han’emon. About Tsuzaki Gosuke I will write later.

Kobayashi received ten koku and an allowance for two retainers. At his disembowelment Takano Kanb seconded him. Hayashi was

originally a peasant in Shimota Village, in Nang

seconded him. Hayashi was

originally a peasant in Shimota Village, in Nang . Tadatoshi picked him up; he gave him a stipend of fifteen koku and an allowance

of ten retainers and appointed him gardener of his Flower Field Mansion. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled

himself at the Butsugan temple. His second was Nakamitsu Hansuke. Miyanaga, a kitchen officer who received ten koku with an allowance for two retainers, was the first man who asked Tadatoshi for permission

to follow him in death. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled himself at the J

. Tadatoshi picked him up; he gave him a stipend of fifteen koku and an allowance

of ten retainers and appointed him gardener of his Flower Field Mansion. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled

himself at the Butsugan temple. His second was Nakamitsu Hansuke. Miyanaga, a kitchen officer who received ten koku with an allowance for two retainers, was the first man who asked Tadatoshi for permission

to follow him in death. On the twenty-sixth of the fourth month he disemboweled himself at the J sh

sh temple. His second was

Yoshimura Yoshiemon. Some of these people were buried at their family temples, some close to Tadatoshi’s mausoleum on the

hill outside K

temple. His second was

Yoshimura Yoshiemon. Some of these people were buried at their family temples, some close to Tadatoshi’s mausoleum on the

hill outside K rai Gate.

rai Gate.

A surprisingly large proportion of these men were those who received their stipends directly in rice. Among them, Tsuzaki Gosuke has a particularly interesting story worth separate telling.

Gosuke, a recipient of six koku with an allowance for two retainers, was the keeper of Tadatoshi’s dogs. He always accompanied Tadatoshi in falconing and was his favorite man during those field excursions. He begged, like a spoiled kid, for permission to follow his master in death, and got it, but the clan administrators all said to him, “The other retainers were granted high stipends and enjoyed some glory, but you were a mere dog keeper to our deceased lord. We understand very well that your sentiments are admirable, and it’s a supreme honor that our lord should have given you permission. We think that should be enough. Will you please give up the thought of dying and serve our new lord?”

Gosuke would not listen. On the seventh of the fifth month he went to the K rin temple near the exercise ground with the dog

he took whenever he accompanied Tadatoshi. His wife saw him off at the front gate and said, “You’re a man, too. Try not to

be lesser in glory than those in senior positions.”

rin temple near the exercise ground with the dog

he took whenever he accompanied Tadatoshi. His wife saw him off at the front gate and said, “You’re a man, too. Try not to

be lesser in glory than those in senior positions.”

The Tsuzaki family’s temple was Oj -in, but because it had some connections to Tadatoshi and so was inappropriate for someone

like himself, Gosuke decided on the K

-in, but because it had some connections to Tadatoshi and so was inappropriate for someone

like himself, Gosuke decided on the K rin temple as a place to die. As he entered the graveyard he saw Matsuno Nuinosuke,

whom he had asked to second him, already waiting. He took down a light-green bag from his shoulder and pulled a lunch box

out of it. He opened its lid and found two rice balls. He put them before the dog. The dog would not begin on them, but looked

up at Gosuke, wagging his tail.

rin temple as a place to die. As he entered the graveyard he saw Matsuno Nuinosuke,

whom he had asked to second him, already waiting. He took down a light-green bag from his shoulder and pulled a lunch box

out of it. He opened its lid and found two rice balls. He put them before the dog. The dog would not begin on them, but looked

up at Gosuke, wagging his tail.

“You are a beast and may not realize it,” Gosuke said to the dog as if he were speaking to a human being. “But your lord who

caressed you on the head many times has already passed away. Many people who enjoyed his favors have already disemboweled

themselves to accompany him. I’m a lowly retainer, but I’m no different from those of higher rank in having received a stipend to live from day to day. We’re the same, too, in having enjoyed our lord’s favors.

That’s why I’m going to die by cutting my stomach. Once I’m dead, you’ll be a stray dog. I feel terribly sorry for you because

of that. Our lord’s hawks dived into the well of Sh ’un-in and died. What d’you say? Don’t you want to die with me? If you

want to live even if you may become an abandoned dog, eat these rice balls. If you want to die, don’t eat them.”

’un-in and died. What d’you say? Don’t you want to die with me? If you

want to live even if you may become an abandoned dog, eat these rice balls. If you want to die, don’t eat them.”

Gosuke looked the dog in the eye; the dog kept looking Gosuke in the eye and would not eat the rice balls.

“So you’ll die with me?” said Gosuke and gave the dog a sharp look. The dog barked once and shook his tail.

“All right, then. I pity you, but die for me.” Gosuke held the dog close, unsheathed his sword, and stabbed him.

He put the dog’s corpse to one side. Then he pulled out of his chest a piece of paper with something written on it, spread it on the ground before him, and put a stone on it as a weight. The paper was folded once–a formality he had picked up at someone’s poetry meeting–and had this written like a regular tanka:

Kar -shu wa tomare tomare to ouse aredo

-shu wa tomare tomare to ouse aredo

tomete tomaranu kono Gosuke kana

The administrators and all tell me to stop, stop it,

but however they try to stop me, Gosuke can’t be stopped

The paper was not signed. He simply thought that because the poem already had his name, he didn’t have to duplicate it by writing it again. In this he was faithful to the tradition without knowing it.

Having decided that he hadn’t left anything undone, Gosuke said, “Mr. Matsuno, now I must ask your help.” He sat cross-legged on the ground and bared his chest and belly. He held the sword stained with the dog’s blood upside down, and said aloud, “I wonder what the falconers have done. His dog keeper now follows him.” He then laughed joyfully and slashed his abdomen crosswise. From behind him, Matsuno beheaded him.

Gosuke’s status was low, but his widow was granted the same benefits accorded the other surviving families of those who followed Tadatoshi in death. This was because his only son had entered the priesthood as a child. His widow received a rice allowance for five retainers and was given a new house. She lived until the thirty-third anniversary of Tadatoshi’s death. The son of Gosuke’s nephew inherited his name, and after that, the Tsuzaki family served in the criers’ unit for generations.

Other than these eighteen men who obtained permission from Tadatoshi and followed him in death, there was a man called Abe Yaichiemon Michinobu. He was originally from the Akashi clan, and his boyhood name was Inosuke. He began serving Tadatoshi very early and had now risen to the status of receiving more than 1,500 koku. During the Shimabara Conquest, three of his five sons rendered distinguished services and each received new land worth 200 koku. All his family expected Yaichiemon to follow Tadatoshi in death, while he himself made clear his wish to die every time his turn at night attendance came around. But no matter. Tadatoshi would not give consent.

“I’m pleased with your sentiments,” Tadatoshi repeated. “But I’d rather you lived on and continued service with Mitsuhisa.”

Tadatoshi had long had a habit of contradicting Yaichiemon. That went back to very early days; even when Yaichiemon was still a page, if he came to ask if he was ready for a meal, Tadatoshi would invariably say, “I’m not hungry yet.” If another boy came to ask, Tadatoshi would say, “All right. Have the meal brought.” There was something about Yaichiemon that tempted Tadatoshi to contradict him. Does this mean he was scolded often? No, that wasn’t the case, either. No one else worked as hard, he noticed everything, and everything he did was faultless. Even if he, Tadatoshi, had a mind to scold him, he wouldn’t have found a chance.

Yaichiemon would do on his own the kind of things other men would do only after being told to. He would do, without telling Tadatoshi, what other men would do only after telling their lord. And whatever he did was to the point and impeccable. It did not take long before Yaichiemon’s attitudes as a servant stiffened.

At first Tadatoshi contradicted the man unthinkingly, but later when he knew that his mind had stiffened, he resented him. While resenting him, Tadatoshi was clear-headed enough to know how Yaichiemon had come to be what he was and realize that he himself was the cause. He wanted to change his habit of contradicting the man, and continued to want to do so, but as months and days passed and as he grew older, changing the habit became harder.

Everyone has someone he likes–and someone he wants to avoid–far above anyone else. When one looks closely for the reasons, one often can’t find anything that can be pinpointed. Tadatoshi’s dislike of Yaichiemon was such a case. Still, there must have been something about Yaichiemon that made it difficult for people to feel friendly to him. For one thing, this was clear from the fact that he had few close friends. Everyone respected him as an outstanding samurai. But no one would approach him in a relaxed manner. At times, an oddball would try to become close to him, but his perseverance would fail in a while and he would begin to stay away. When Yaichiemon was still called Inosuke and wore bangs, one of his seniors who had often talked to him and helped him in various ways finally gave up by saying, “You can’t get a crack at him.” When you think about such things, it is no mystery that Tadatoshi could not change his habit though he wanted to.

In any event, while Yaichiemon was unable to get his permission despite his repeated requests, Tadatoshi died. A little before Tadatoshi’s death, Yaichiemon looked his master in the eye and said, “Sir, never have I asked you a favor. This is the first and only favor I ask in my whole life.” Tadatoshi returned Yaichiemon’s steady gaze and declared, “No, will you please continue service with Mitsuhisa?”

Yaichiemon thought hard about the situation and made up his mind. A hundred men out of a hundred would think it impossible for someone with my status not to follow his lord in death but to survive him and continue to face the retainers of the clan. In the event, the only thing left for such a man would be either to disembowel himself, knowing that would be a dog’s death, or to leave Kumamoto master-less. But I am what I am. Let them think what they like. A samurai is no concubine. That I wasn’t liked by my master doesn’t mean the loss of my reason for being. That was what he thought, and he kept going to work every day as he had.

The seventh of the fifth month came and went. By then all of the eighteen men had followed Tadatoshi in death. Throughout Kumamoto people talked only about these men. There was no other talk than who said what at the moment of death, how so-and-so’s manner of death was superior to everybody else’s, and so on. Even before all this, Yaichiemon had had few who would talk to him except about work, but after the seventh of the fifth month he found himself far more isolated in his office at the castle. He knew his colleagues tried not to look him in the eye. He knew they looked at him only when he was looking away or when his back was turned. This was extremely unpleasant. But, he thought, I’m alive not because I hold my life dear. Even someone who thinks the worst of me couldn’t possibly think I hold my life dear. If it was all right to die, I’d be glad to die right on this spot. So he continued to go to his office carrying his head high and leaving his office carrying his head high.

A few days later an outrageous rumor reached his ear. Who began it was unknown, but it went like this: “Abe stays alive, it appears, glad that he didn’t get his permission. Even without it one could disembowel oneself if one wanted to. Abe’s belly skin seems different from an ordinary man’s. He should perhaps oil a gourd and cut his belly with it.” To Yaichiemon this was unexpected. Anyone who wants to speak ill of me may say whatever he pleases, he thought. But how can anyone look at me, be it from straight ahead or from the side, and say I’m a man who holds his life dear? Someone who’s determined to say something bad certainly can. All right. I’ll oil a gourd and cut my belly with it to show them.

That day, as soon as he left his office, Yaichiemon sent urgent messengers to summon to his mansion in Yamazaki two of his

younger sons who now lived independently. He had the furniture between the living and guest rooms taken away, and waited formally

with three of his sons sitting beside him: the first son, Gonb ; the second son, Yagob

; the second son, Yagob ; and Shichinoj

; and Shichinoj , the fifth son, who

still wore bangs. Gonb

, the fifth son, who

still wore bangs. Gonb , whose boyhood name was Gonjur

, whose boyhood name was Gonjur , rendered distinguished services during the Shimabara Conquest and

received new land worth 200 koku. He was as remarkable a man as his father. About the recent situation, he had asked his father

only once, “So you did not get your permission,” to which the father had said, “No, I didn’t.” There was no further exchange

on the subject between the two. They understood each other so completely that nothing more needed to be said.

, rendered distinguished services during the Shimabara Conquest and

received new land worth 200 koku. He was as remarkable a man as his father. About the recent situation, he had asked his father

only once, “So you did not get your permission,” to which the father had said, “No, I didn’t.” There was no further exchange

on the subject between the two. They understood each other so completely that nothing more needed to be said.

Soon two lanterns came through the gate. The third son, Ichi-day , and the fourth son, Goday

, and the fourth son, Goday , almost simultaneously arrived

at the entrance, took off their raincoats, and came into the room. Humid rain had started the day after the forty-ninth day

after Tadatoshi’s death, and the heavy, dark sky of the fifth month hadn’t had a chance to clear up. The sliding doors were

all left open, but it was muggy and windless. Yet the candle flames on candlesticks were wavering. A single firefly passed

by through the trees in the garden.

, almost simultaneously arrived

at the entrance, took off their raincoats, and came into the room. Humid rain had started the day after the forty-ninth day

after Tadatoshi’s death, and the heavy, dark sky of the fifth month hadn’t had a chance to clear up. The sliding doors were

all left open, but it was muggy and windless. Yet the candle flames on candlesticks were wavering. A single firefly passed

by through the trees in the garden.

The master of the house looked around at those who had gathered, and opened his mouth.

“Gentlemen, I thank you for coming even though I sent for you in the dark. I heard the rumor is already known to all the retainers of this clan, so I think all of you have heard it, too. They say my belly is such that I can cut it only with an oiled gourd. So I’ll cut it with an oiled gourd. Kindly witness how I do it.”

Both Ichiday and Goday

and Goday had set up separate households after each was granted new land worth 200 koku for his military exploits

at Shimabara, but of the two Ichiday

had set up separate households after each was granted new land worth 200 koku for his military exploits

at Shimabara, but of the two Ichiday , who had been assigned to the heir apparent early on, was among those who came to be

envied as the rulers changed. He edged forward on his knees a little toward his father:

, who had been assigned to the heir apparent early on, was among those who came to be

envied as the rulers changed. He edged forward on his knees a little toward his father:

“I understand you perfectly, sir. Some of my colleagues said, ‘We hear your father continues his service according to our deceased master’s will. We’d like to express our congratulations that both fathers and sons can work together for our lord.’ The way they said it made me gnash my teeth.”

Yaichiemon, the father, laughed. “I know how you felt. Don’t get involved with those nearsighted bastards. I’m not supposed to die but I will; they will then insult you after my death as the sons of the man who couldn’t get his permission. It was part of your fate that you should have been born my sons. When you have to suffer shame, suffer it together. Avoid fighting among yourselves. Now, look how I cut my belly with an oiled gourd.”

Having said this, Yaichiemon disemboweled himself right in front of his sons, then stabbed himself in the neck from left to right, and died. His five sons, who had been unable to fathom their father’s mind, felt sorrow; but at the same time they felt they had stepped out of a precarious place and put down one of the burdens they had carried.

“Big brother,” said the second son, Yagob , to the first son. “Father told us not to fight among ourselves. No one would object

to that. In Shimabara I wasn’t in the right place and wasn’t granted any land, so I’ll have to depend upon you from now on.

But whatever may happen, you have a reliable spear in your hand. You may count on that.”

, to the first son. “Father told us not to fight among ourselves. No one would object

to that. In Shimabara I wasn’t in the right place and wasn’t granted any land, so I’ll have to depend upon you from now on.

But whatever may happen, you have a reliable spear in your hand. You may count on that.”

“We all know that. I don’t know what’s going to happen, but the land I get is your land,” Gonb said curtly, and folded his

arms with a frown.

said curtly, and folded his

arms with a frown.

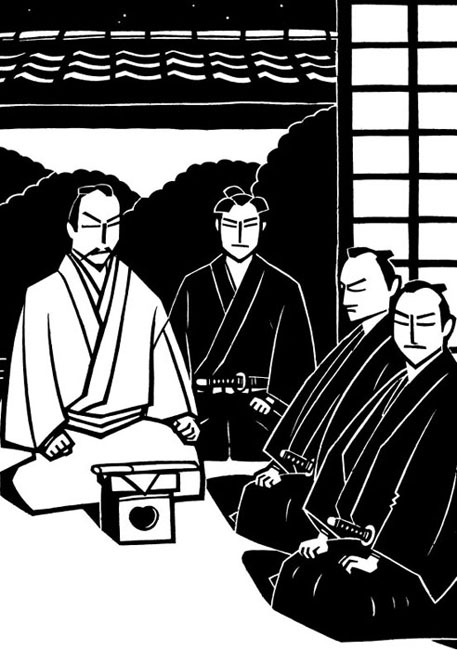

Abe Yaichiemon and his Sons

“Exactly,” Goday , the fourth son, said. “We can’t be sure what will happen. There will be some who say disembowelment without

permission isn’t the same as following one’s lord with his consent.”

, the fourth son, said. “We can’t be sure what will happen. There will be some who say disembowelment without

permission isn’t the same as following one’s lord with his consent.”

“That’s too obvious. But whatever may happen,” said Ichiday , the third son, looking straight at Gonb

, the third son, looking straight at Gonb , “whatever may happen,

let’s not separately deal with our opponents but stay together all the time.”

, “whatever may happen,

let’s not separately deal with our opponents but stay together all the time.”

“We will,” said Gonb , but he didn’t seem relaxed about it. He always thought of the good of his brothers, but he was one

of those who are unable to express themselves with ease. Further, he tended to think and do things by himself. He seldom consulted

others. That’s why Yagob

, but he didn’t seem relaxed about it. He always thought of the good of his brothers, but he was one

of those who are unable to express themselves with ease. Further, he tended to think and do things by himself. He seldom consulted

others. That’s why Yagob and Ichiday

and Ichiday pinned him down this way.

pinned him down this way.

“If they knew you, my big brothers, stood together, they wouldn’t dare talk ill of our father,” said Shichinoj , the son who

still had bangs. His voice, thin as a girl’s though it was, was weighted with such strong conviction that to everyone sitting

there it was like a streak of light illuminating the darkness ahead.

, the son who

still had bangs. His voice, thin as a girl’s though it was, was weighted with such strong conviction that to everyone sitting

there it was like a streak of light illuminating the darkness ahead.

“Now,” Gonb stood up, “I must go tell mother to ask the womenfolk to take leave of our father.”

stood up, “I must go tell mother to ask the womenfolk to take leave of our father.”

The succession ceremonies of Mitsuhisa, Junior Fourth Rank, Lower Grade, Chamberlain, and Governor of Higo, were completed. New lands or increased stipends were granted and assignments reshuffled for the retainers. All heirs of the eighteen samurai who followed Tadatoshi in death succeeded to their fathers’ positions. As long as there was an heir, there was no exception. These men’s widows and old parents were given allowances; houses and mansions were given to some, and even repairs were taken care of by the government. The eighteen were the men favored enough by the previous master to be allowed to accompany him on his way to death, so some in the fiefdom may have felt envious, but none jealous.

The treatment of the succession of Abe Yaichiemon’s surviving family, however, was somewhat different. The heir, Gonb , was

not allowed to succeed to his father’s position as it was. Yaichiemon’s land, worth 1,500 koku, was splintered among the five

brothers. The total of the family members’ land holdings remained the same, but the status of Gonb

, was

not allowed to succeed to his father’s position as it was. Yaichiemon’s land, worth 1,500 koku, was splintered among the five

brothers. The total of the family members’ land holdings remained the same, but the status of Gonb , who succeeded to the

main house, was downgraded. Needless to say, Gonb

, who succeeded to the

main house, was downgraded. Needless to say, Gonb felt he’d shrunk in stature. His brothers didn’t feel good, either. Each

man’s holdings increased, to be sure, but till then their main house with holdings of more than 1,000 koku had made them feel

that they stood under a giant tree, whereas now they felt like acorns trying to see which is taller than the others, as the saying goes. As a result, they knew they ought to be

grateful, but in fact felt put upon.

felt he’d shrunk in stature. His brothers didn’t feel good, either. Each

man’s holdings increased, to be sure, but till then their main house with holdings of more than 1,000 koku had made them feel

that they stood under a giant tree, whereas now they felt like acorns trying to see which is taller than the others, as the saying goes. As a result, they knew they ought to be

grateful, but in fact felt put upon.

Government prompts no one to seek a scapegoat as long as things stay on a normal course. An inspector-general10 at the time, who happened to enjoy the present ruler’s favor and served very near him, was a man by the name of Hayashi Geki.

Clever in small matters, he was suited to the role of companion that he had held when Mitsuhisa was the heir apparent; but

he was somewhat lacking in the ability to see an overall picture and tended to get bogged down in details. He decided a line

had to be drawn between Abe Yaichiemon, who chose death without the late lord’s permission, and the other eighteen men who

died true to form. Accordingly, he recommended that the Abe family’s holdings be divided. Mitsuhisa, later a thoughtful daimyo,

had little experience as yet. He gave little consideration to Yaichiemon and his heir Gonb , whom he did not know. He adopted

Geki’s recommendation simply because he noted a point in it that indicated an increase in the holdings of Ichiday

, whom he did not know. He adopted

Geki’s recommendation simply because he noted a point in it that indicated an increase in the holdings of Ichiday , with whom

he was familiar as he kept him in close employment.

, with whom

he was familiar as he kept him in close employment.

When the eighteen men killed themselves to follow their lord, many of the retainers of the Hosokawa clan despised Yaichiemon because he had not done the same even though he had served near Tadatoshi. Now, only a few days later, Yaichiemon disemboweled himself with dignity. But, regardless of the right or wrong of the matter, contempt, once expressed, is hard to fade away: There was no one who would praise Yaichiemon now. In allowing the Abe to bury Yaichiemon alongside Tadatoshi’s mausoleum, the government should have gone a step further and, instead of forcing a line to be drawn in succession matters, treated the family in the same way as those of the other eighteen men. Had it done so, the Abe family would have felt honored and competed among themselves in loyalty. As it was, however, by placing the family a step below the others, the government put an official stamp on the contempt the retainers felt for the Abe family. Yaichiemon’s sons were gradually alienated from their colleagues, and they lived from day to day in great discontent.

The seventeenth of the third month of the nineteenth year of Kan’ei came around. It was the first anniversary of the death

of the previous lord. The My ge temple next to the mausoleum had yet to be built, but there was a hall called K

ge temple next to the mausoleum had yet to be built, but there was a hall called K y

y -in built, where

Tadatoshi’s memorial tablet bearing his Buddhist name, My

-in built, where

Tadatoshi’s memorial tablet bearing his Buddhist name, My ge-in-den, was kept and where a monk by the name of Ky

ge-in-den, was kept and where a monk by the name of Ky shuza resided

as chief priest. Days before the anniversary, Priest Ten’y

shuza resided

as chief priest. Days before the anniversary, Priest Ten’y arrived from the Daitoku temple, of Murasakino, Kyoto. Apparently

the anniversary ceremonies were going to be a splendid affair; for about a month, the castle city of Kumamoto busied itself

in preparations.

arrived from the Daitoku temple, of Murasakino, Kyoto. Apparently

the anniversary ceremonies were going to be a splendid affair; for about a month, the castle city of Kumamoto busied itself

in preparations.

The day came. The weather was fine and warm, and the cherries alongside the mausoleum were in full bloom. A curtain was set

up around the K y

y -in and foot soldiers guarded it. Mitsuhisa came in person and first offered incense before his late father’s

tablet, then before the tablet of each of the nineteen men. Next, the men’s relatives were allowed to do the same. They were

also presented with ceremonial wear bearing the Hosokawa crest, as well as seasonal suits: naga-kamishimo for those of the rank of mounted escort and above and han-gamishimo for those of the rank of foot soldier. Those of lower rank received monetary gifts for services for the deceased.

-in and foot soldiers guarded it. Mitsuhisa came in person and first offered incense before his late father’s

tablet, then before the tablet of each of the nineteen men. Next, the men’s relatives were allowed to do the same. They were

also presented with ceremonial wear bearing the Hosokawa crest, as well as seasonal suits: naga-kamishimo for those of the rank of mounted escort and above and han-gamishimo for those of the rank of foot soldier. Those of lower rank received monetary gifts for services for the deceased.

The ritual proceeded free of trouble, except for one strange thing that happened. When Abe Gonb , as a member of the surviving

families of the deceased, went, in his turn, before Tadatoshi’s memorial tablet, he unsheathed his dagger as soon as he finished

offering incense, cut his topknot, and laid it in front of the tablet. Taken aback by this unexpected behavior, the samurai

overseeing the services looked on a while in confusion. It was only when Gonb

, as a member of the surviving

families of the deceased, went, in his turn, before Tadatoshi’s memorial tablet, he unsheathed his dagger as soon as he finished

offering incense, cut his topknot, and laid it in front of the tablet. Taken aback by this unexpected behavior, the samurai

overseeing the services looked on a while in confusion. It was only when Gonb walked back several steps with calm dignity

as if nothing had happened that one samurai came to himself and ran up to Gonb

walked back several steps with calm dignity

as if nothing had happened that one samurai came to himself and ran up to Gonb , shouting, “Mr. Abe, wait, sir!” and stopped

him. A couple of others joined him, and they took Gonb

, shouting, “Mr. Abe, wait, sir!” and stopped

him. A couple of others joined him, and they took Gonb to another room.

to another room.

When questioned by the overseers, Gonb explained: You might think I’ve gone mad, but not at all. My father Yaichiemon served