Digging for the Roots

History is written by the victors. Whenever cultures clash, the dominant force is the one left to record the events of the past for future generations. Those defeated leave behind physical artifacts, and even folk tales and myth, but their way of life is lost in the march of time. Whenever you are digging through the roots of history, be aware of this fact. Although actual events are objective, a viewpoint of those events is subjective, depending on your previous beliefs. If you read about the American Revolution, written by an American, the text would be biased in favor of the American heroes, with the British as the villains. If you read about the same events from a British author, the objective facts, dates, and locations would be the same, but the tone would be very different. The same could be said for most conflicts in history, and the more subtle cultural revolutions that are not as well documented. Every culture has its own point of view. Even when a writer is aware of such a bias, it can be difficult to separate from such a key element of one’s personal identity.

When we are digging for the roots of witchcraft, we must keep in mind that the practitioners of the craft were seldom the victors over the last two thousand years, so our common history is colored. Much of their point of view has been lost to us. As historians, anthropologists, scholars, teachers, and students, we can reclaim and reconstruct, but we can never really know the truth.

The facts of witchcraft and ancient spiritual traditions are shrouded in mystery and misunderstanding because they were almost completely vanquished by the conquering forces of Europe. Everyone telling the story has a bias. Traditional researchers do not want to challenge what they “know” to be fact and dismiss any theories to the contrary. Those excited by the prospect of ancient religions can let their modern enthusiasm cloud their less biased analytical skills. People involved in modern pagan religions have a strong bias as well. Practitioners and teachers like myself have a vested interest in showing the beneficial aspects of witchcraft throughout history, while discrediting the misconceptions surrounding it.

For many years, I wanted to know exactly what happened. I wanted information on the ancient rituals and practices. I needed to know exactly where my witch roots came from, and how my spiritual ancestors practiced. And I was disappointed. There is no definitive history accepted by everyone. No one could tell me the ancient rituals and stories, unchanged.

I now welcome the multitude of well-thought-out, researched views, but I am no longer attached to the idea that any one history is more correct than any other. The literal facts of our history may never be known beyond a shadow of a doubt, and they do not need to be. Our history has changed so much in the last hundred years, but such new revelations do not change how I practice witchcraft today. My practice changes as I grow and evolve. I am open to personal revelations as well as historical information. My foundation is based on those who have come before me, and that foundation is as solid as I need it to be.

Many of the early books and stories used as a foundation by Wiccans have been somewhat discredited by later scholars, but that does not mean the wisdom of the culture they drew from is discredited. It only means that we are still looking at their truths. Think of such works as poetic histories, if not literal ones, and be inspired by the words of those who came before you.

For modern witches, the history of the craft is told orally, as the story of a people’s journey over time. Our history is a living story. We are a part of it. We are writing our own chapter now. Our children will continue the story, and hopefully it will never go so far underground that it will be lost again.

The Stone Age

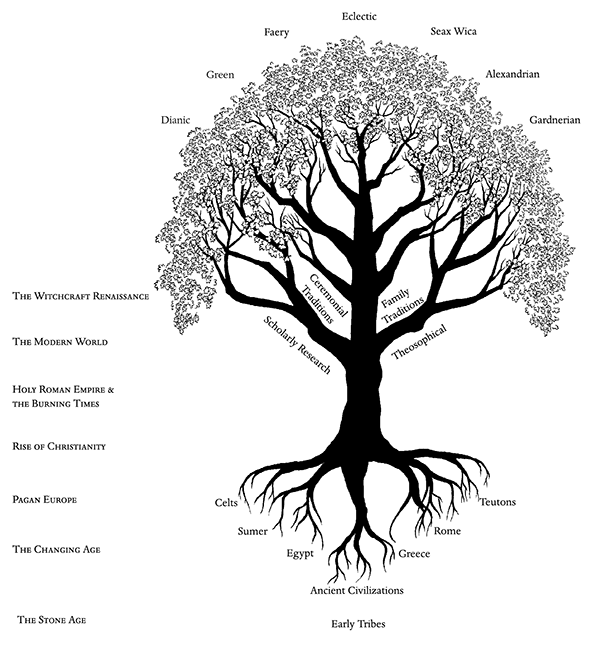

For me, the roots of the great tree of witchcraft stretch deep into history, to our earliest ancestors. In the Paleolithic era, the early Stone Age, human societies were hunters and gatherers, nomadic people continuously following the source of food. Most modern people think of the Paleolithic times as the age of barbaric cavemen, but these tribes were probably more sophisticated than we give them credit for. In those societies, the men usually hunted for food, while the women stayed with the tribe, caring for the family. Women were logically considered the lifeblood of the tribe, and cherished, since women gave birth to the children. Men were more “expendable” in terms of survival, since one man could impregnate many women. Scholars speculate that the role of man in pregnancy was not even understood in Stone Age times. In this harsh life, children were vital to continuing the tribe. This gave rise to the belief that many of these societies were matriarchal, meaning they were led by women. These societies were more right-brained, focusing on pictures, feelings, and instinct.

Religiously, cave painting and other artifacts indicate a level of spiritual belief. We believe that these early people saw the divine in nature, animated by nature spirits or gods. The Earth was the mother of life, providing the vegetation needed to survive, while her consort was an animal lord, providing the animals needed by the people. Stone Age people were polytheists, believing in more than one god. Other spirits possibly animated the sky, storms, mountains, rivers, and fire.

Certain members of the tribes noticed that they had abilities that set them apart from their kin, and some developed these abilities further. Women and men who were either too old or too injured to hunt lived lives that allowed them the opportunity to expand these abilities. Notice that our surviving archetypes of these people are the wise old women and men, and often such sages are called wounded healers, their injuries helping them understand the nature of healing. These individuals developed their natural rapport with the spirits, developing psychic talents, knowledge of herbs and other healing skills, and becoming the wise ones of the tribe. They became the religious leaders, petitioning the elements and leading hunters to the herds. They conducted ceremonies and celebrations. They were the magick makers. Such people did not necessarily use the word witch or witchcraft, but in essence, this was their practice. They were akin to the Native American shamans, but we do not have a proper name for the shamans’ ancient European, African, or Middle Eastern brethren. To me, they were witches in every sense of the word. Anytime a people honored both Mother and Father aspects of the divine, revered nature, and shaped the forces of the world for healing and change, they were practicing witchcraft. No one culture owns the tenets of witchcraft. They are universal.

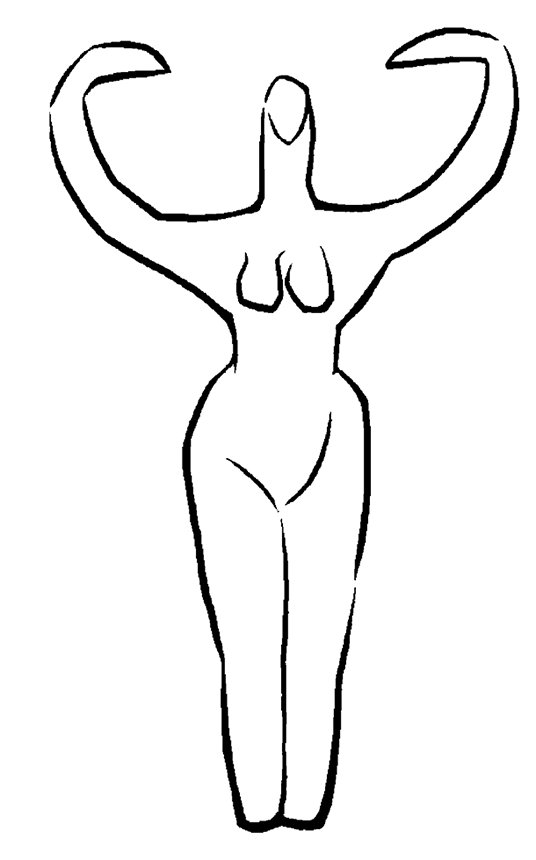

As women were so critical to the development of witchcraft, the Goddess played a pivotal role in its development, then and now. Humanity’s earliest works of art and religion are based on Goddess figures, images that we now believe represent the Great Mother. In the earliest creation myths, the Mother was often the prime source of creation, self-fertilizing and single-handedly manifesting reality from the void. Similar images are found all over the world, depicting She of a Thousand Names, the mother of witchcraft (figure 1).

The Changing Age

Goddess-oriented scholars suspect that this culture dominated until the rise of the patriarchal religions, near the time of Abraham, the first prophet of Yahweh. From that point on, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction, and the goddess cultures in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East slowly lost their foothold in our world, to the point that we now doubt their existence at all, since they seem so different from our “normal” conceptions of religion and reality. We now sit on the cusp of a new shift, with the potential to strike a balance between the two and synthesize the best of each, achieving a state of harmony.

Aleister Crowley, modern magician and scholar, divided the ages into three categories, based on Egyptian myth. The current age we are leaving is the Age of Osiris, marked by sacrificial gods such as Osiris, Dionysus, and even Jesus. The previous age was the Age of Isis, when the goddess cultures dominated. We affectionately call it the “cradle of civilization.” We are entering the next great age, the Age of Horus, the child of Isis and Osiris, the young god who possessed the powers of both Mother and Father. Although I don’t agree with everything Crowley said or did, I think this metaphor is quite appropriate. The Age of Aquarius, or New Age, is another name for the current shift.

Venus of Willenorf 30,000 b.c.e.

Venus of Lespugue 25,000 b.c.e.

Nathor, Nile River Goddess 4000 b.c.e.

As we continue through the middle, or Mesolithic, Stone Age, and the new, or Neolithic, Stone Age, which occurred at different points in different locations across the world, weather patterns changed and food became more available. Nomadic tribes settled down and learned the arts of agriculture. Crude stone tools become more sophisticated. Pottery and other arts expanded. Agricultural settlements continued to grow, and what modern people call “civilization” developed. The ancient lands of Egypt, Sumeria, and Greece became beacons for the new agricultural revolution. The American and Asian settlements developed into the ancient cities and sophisticated cultures. Monuments were built, and, with the advent of writing, histories were recorded.

As larger groups of people gathered together, the number of healers and magick workers in each community increased. Solitary and small groups of practitioners organized into orders of priests and priestesses. Personal experiences and tribal wisdom evolved into cultural mythologies. Such wise ones continued to counsel and heal, often working for the rulers of the emerging empires. As religion played an important part in the secular world, these brotherhoods and sisterhoods held a great deal of clout in society. The orders developed sophisticated religious and magickal systems, establishing mystery schools to educate and initiate the seeker. They continued to act as intermediaries, but spirituality still contained a very personal spark and flair to it. Worship of the deities was a daily event conducted by both priests and the general populace.

The similarities of gods, rituals, and teachings from culture to culture is now evident from our twenty-first-century perspective, inspiring some to see a central root culture influencing them all, possibly the ancient anecdotal myths of Atlantis or Lemuria, but no definitive evidence exists for such a connection. Quite possibly each society was tapping into the same fundamental archetypal energies of that time, and each expressed them a bit differently.

From this era we draw on the familiar pantheons of classical mythology. The godforms of the Middle East migrated into the pantheons of Greece and later Rome. Toward the beginning of this period, there was a strong goddess reverence, harkening back to the earlier Paleolithic tribes. As living conditions improved, the pendulum of social trends swung toward a patriarchy, as evidenced by the change in many myths. Powerful goddess myths were retold with new twists, often disempowering many of the goddesses. In her book When God Was a Woman, Merlin Stone does an excellent yet controversial job tracing this transformation of deity.

Pagan Europe

When these ancient civilizations were thriving, the less structured tribes of Europe, north of the Mediterranean Sea, were developing their own customs and magick that were no less powerful, but less formalized and documented than others. The Celtic people were migrating west, across Europe, and eventually came in contact with the Greeks and Romans.

The ancient Celts were very complex and culturally different from the “civilized” cultures of the time. Scholars believe they came from a common Indo-European root with the Hindu culture. One band moved west across Europe and another moved east to populate India. Common points of language, myth, and art support this theory. Look at Celtic knot work and Indian art with geometric patterns. The Celtic version is softer and rounded, but they are similar. Celtic stories of the dark goddess figure the Caillech survive today, striking a similar phonetic and magickal resonance with the dark Hindu goddess Kali. The Celts were warriors, but had an unusual code of ethics compared to Greco-Roman society. They did not conquer for resources, or to subjugate people, but as a sign of prowess, and were as likely to fight among themselves as against “outsiders.” They did not push their own ideology, and quite often incorporated much of the myth, culture, and wisdom of the people they conquered into the Celtic worldview. Such absorptions, along with the lack of a written language, account for the somewhat disjointed mythos of the Celts when compared to the Greeks, Romans, or Egyptians.

The Druids were the religious leaders of the Celts. The generally accepted meaning of the word Druid is “to know the oak.” Oak trees are symbols of life and death, and the Druids had knowledge of the spirit world, magick, and nature. They conducted ceremonies, counseled kings, and performed healing. They settled disputes, not bound by the identity of individual Celtic tribes. They were both honored and feared for their role, seen not as gods, but as the sacred interpreters of the gods’ will. My first teachers of the craft taught me that the roots of witchcraft came from the legacy of the Druids, who were both male and female, though most historical accounts portray them as exclusively male.

As the Celts come from a warrior culture, scholars dispute the dominance of the goddess in the Druids’ theology, seeing them as being primarily concerned with solar figures and animal lords. Many goddess myths play an important part in surviving Celtic culture, but we are uncertain where those myths came from: the Druids themselves, or the cultures the Celts conquered. I feel the sacredness of nature, of the forest, of life, and of death are very goddess oriented, and the Druids saw the benefits of both aspects of the divine. The dark warrior goddesses reach back to the heart of the Celtic people.

The Celts eventually based themselves in Gaul, which encompasses modern-day France, and some migrated to the British Isles, involving themselves with the inhabitants of the isles, the Picts. The Pict society harkened back to the Stone Age era. It is likely that the Picts and Celts influenced each other. Because of their shorter stature, the Picts are sometimes theorized to be the genesis of the “little people,” the faery folk in Celtic myth.

At the time of the Celtic settlement in Gaul, the Roman Empire was in full swing. Empires are only prosperous while they continue to expand, and Julius Caesar set out to conquer Gaul and the tribes living there. He met resistance, but was eventually successful. The people were “Romanized” and the empire ultimately included parts of Britain. The Romans at the time were still polytheistic, and a general mingling of myths occurred between these cultures. The witchcraft of the Romans and the Etruscans from northern Italy could have intermingled with the magick of the Druids.

Caesar was a scholar of his time, recording his encounters with the Celtic people and the Druids. Unfortunately, the few written accounts of the Druidic priests come from Caesar. Though I do not disparage Julius Caesar’s scholarly abilities, we must bear in mind his personal biases. Here we have a leader of an empire conquering a people through military might. The Druids were the organizing force between Celtic tribes. Though the tribes held a similar identity, there was no hierarchy to the leaders, but everyone would listen to the word of the Druids. If Caesar extolled the virtues of the Druids and the Celts to his people, they might have questioned his decision to subjugate them. If he painted a darker portrait, there would be no chance of public outcry. Caesar spoke of human sacrifice performed by the Druids. Such claims may or may not be true, but you must remember that we live in a world where many states and countries still have the death penalty. What is accepted in one culture, place, and time may not be accepted in another.

The Druids, on the other hand, have no surviving documentation written from their own point of view. The Druidic tradition was oral, involving at least nineteen years of intensive study and memorization, a period of the great lunar cycle, what the Greeks called the Meton cycle. Druids had in-depth knowledge of magick, medicine, poetry, music, history, mythology, astrology, and astronomy, but did not commit their knowledge to paper. Writing was seen as sacrilegious. If the information was important or sacred, one did not write it down. To write something down meant it was a minor thing, unimportant, and not worth committing to memory. Part of the Druids’ training was bardic, meaning they learned the oral traditions, stories, myths, and songs. While it appears that the Druids were wiped out, they most likely went into hiding, as the bards and storytellers of the people, keeping the culture alive through its art. Others gave up the mantle of priest or priestess and became healers. They lived on the outskirts of civilization, keeping the ways of nature and offering their services when they could.

Similar to the Celts in many ways, yet fundamentally different, were the Teutonic tribes of northern Europe, eventually becoming the German and Nordic tribes. The word Teuton is now a synonym for German, but at the time, it encompassed a larger group of people. These tribes honored the shifts in the Sun as the equinoxes and solstices, performed intricate magick, particularly that of the runes, and had a complex mythological, religious, and shamanic tradition. They had some contact with the Celtic tribes, and made their way into Gaul. The Germanic tribes also did battle with the Roman Empire. The Teutons are not credited with the rebirth of Wicca as much as the Celts, but their practices definitely played a part in the revival, particularly as their myths mingled with the Celts and Saxons in later periods.

The Rise of Christianity

During this time, a new religion took root, heralded from the Middle East. The name of this new faith was Christianity, based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, also known as Jesus Christ. He preached a faith of unconditional love while he performed miracles of healing. After Jesus’ death, a new religion sprung up around him, based on the testaments of his apostles. The teachings of certain sects within this early church, particularly those of Gnostic Christianity, were quite mystical and personal traditions. Reincarnation, healing, and trance work were part of the religion. Later, the teachings other than Gnostic were codified into one Church, with a strict dogma and much less personal mysticism.

A small number of modern witches feel Jesus was fundamentally a witch in action, if not in name, traveling with twelve apostles plus himself, creating the traditional number of a coven, and doing acts of magick. He is also seen as an expression of the sacrificed-god archetype, found many places in the world, such as the Egyptian god Osiris, the Greek Dionysus, and the Celtic sacrificed king. In Christian mythology, Jesus Christ resurrected himself after death, and was associated with vegetation, most notably grapes and wine, like Dionysus. Ironically, the early Christians were persecuted by the western Roman Empire, giving us the popular image of the Christians being thrown to the lions. The Romans thought they were cannibals, eating flesh and drinking blood.

Soon after the rise of Christianity, the Roman Empire underwent a fundamental shift. The Edict of Milan in 313 c.e. made Christianity the official religion of the Empire. Churches were constructed over the temples of the old pagan gods. Pagan practices were systematically denounced and outlawed. The horned gods of the Celts, known as Cernunnos or Herne, and the Greco-Roman horned satyr god Pan, were fused with the Hebrew myths of Lucifer, the fallen angel, and Satan, the tester of faith. Together they became the Devil, the source of evil, temptation, and sin in Christian doctrine. The word Devil comes from a corruption of a Greek word, as does demon. Devil is from diabolos, meaning “accuser,” and demon from daimon, translating to “divine power,” referring to an intermediary spirit between humans and the gods, much like an angel.

Pagan rituals were absorbed into the Christian calendar to speed conversion. Any unsavory aspects of the holidays, such as dancing with animal masks, were legally banned, though many pagan elements linger to this day. The craft of the witch was often divided by the public into “good,” or white, witchcraft, being of benefit to the greater society, like the cunning folk with cures and divinations, and “evil,” or black, witchcraft, practiced by those seeking to harm individuals or the greater community. Black magickal practices were legislated against by the local governments and Roman law, while white witchcraft was somewhat welcomed, or at least tolerated; but eventually, the line between the two types of witchcraft blurred in the eyes of the law.

Interestingly enough, in many cases, asking a white witch to place a curse on someone who purposely had done wrong, such as a thief or murderer, was not considered an evil act, though most contemporary witches would abhor such a request. Modern witches would also not usually divide themselves into categories of white and black. Such labels have a smack of inherent racism, assuming black to be bad and white to be good. It also dishonors the loving and healing dark goddesses so popular in the current practice of the craft.

Although witch is the commonly recorded English word for these practitioners, drawing on the Anglo-Saxon entomology, magickal practitioners were known by many other names and titles, including magician, magus, wizard, warlock, and sorcerer. Each has a different connotation regarding powers, morality, and gender of the practitioner, depending on the area and time period when used. For example, the word sorcerer has a wide range of meanings. In Europe, it often denoted an evil practitioner, stemming from the Eastern school of thinking where sorcery is a base art. A sorcerer gets trapped in the accumulation of power without seeking enlightenment. In South America, a sorcerer is a holy man, a shaman and spiritual warrior held in high regard. In Africa, medicine men were considered witch doctors, perhaps because they offered healing and protection from the spells of “evil” witches.

The important thing to remember about these various names and terms is that the actual word witch is fundamentally European, and was introduced into other cultures as an equivalent translation to a word from that culture’s words. As European influence became more dominant, the indigenous culture’s words fell into disuse and were commonly replaced in the general vocabulary. Christian Europeans told many of the indigenous people they conquered that a witch is a practitioner of evil, but the Christians believed that all forms of magick that were not done by a priest were evil, coming from the Devil. Unfortunately, many native people took the word witch to mean “evildoer,” rather than equate it with their own shamans and healers. To this day, many practitioners of the Native American traditions shudder when Wiccans refer to themselves as witches.

Christians looking for an excuse to condemn witchcraft will quote the Bible, “Suffer not a witch to live,” from Exodus 22:17. This passage has been translated many times. In older versions of Exodus, the meaning was “Thou shall not suffer a sorceress to live.” In this particular setting, a sorceress referred to a poisoner, a murderer. The original meaning was “suffer not a murderer to live,” which eventually got confused with the word witch, causing misunderstandings to this day. Ancient Hebrews did not outlaw the practice of magick. In fact, the rabbis were practitioners in the tradition of King Solomon, keeping knowledge of the Kabalah, their mystical teachings. I think most people would agree that being a witch does not mean one is a murderer. Unfortunately, many old Inquisitors had no problem assuming that the two go hand in hand.

The Holy Roman Empire

and the Burning Times

The western Roman Empire declined greatly in power over the fifth and sixth centuries, until it was in complete disarray. By 500 c.e., the Romans left the British Isles in a state of confusion, fending off Saxon invaders. Here we have the generally accepted time period of King Arthur’s Camelot, though the historical setting differs greatly from our romanticized literary version. The Celtic Christian Church existed, but was highly influenced by pagan traditions.

In 800 c.e., the Holy Roman Empire was established when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans.” As the original western Roman Empire fell, the Catholic Church, led by the pope, was the one institution that remained stable and in power over this time. The Church’s power was threatening to the eastern Byzantine Empire and the marauding Lombards. The Church looked to the Frankish kings for protection, and through the recently converted pagans, built a Christian empire. Although many converted to Christianity, some did not, and kept their ways private and secret in the countryside. The practices of the old faith were generally discouraged by the dominant Church, even those of “white” witches, whom some Christians considered more harmful than the “black” ones, because they were thought to be doing “the Devil’s work” and passing it off as healing.

The Inquisitions were originally intended to seek out and punish heretics. Anything that contradicted official Church doctrine was considered heresy. Originally, witchcraft and sorcery laws were considered civil concerns, punishable by fines or imprisonment. Through the Inquisitions, all forms of witchcraft, which by its very nature is a form of worship unsanctioned by the Church, were defined as heresy, punishable by death. Ironically, the root of the word heresy comes from the Greek word hairesis, meaning “free choice.”

Now we enter the witch’s holocaust, the Burning Times, a term coined by modern witches for the extended period of witch trials and executions in Europe and the American colonies. The phrase refers to the popular method of execution by burning at the stake, though hanging and drowning were common, too.

Starting in the fifteenth century, various people, usually enemies of the Church or political figures, were accused of witchcraft, and tried and sentenced to death. The trials did not end until the eighteenth century, roughly the life of the Holy Roman Empire, and in total, the death count will never be known, but has been conservatively estimated from several thousand to as many as nine million. The more reasonable estimates are closer to 200,000. In any regard, the Burning Times was the first, and often forgotten, holocaust in Western history.

In short, all those who did not agree with the Church, including those practicing old pagan folk magick, Jews, healers, and other “heretics,” were accused of renouncing the one true God and making a pact with the Devil. As Christianity branched out into sects, they accused each other of Devil worship. With the discovery of the New World, Native Americans were tagged with this label.

Assumed to be part of the pact with the Devil were acts of magickal violence against the common folk. If anything unfortunate occurred, one looked for a witch in the village, and often the finger was pointed at the person causing the most trouble, or liked the least by the local citizens. Wise women, herbalists, and midwives were included, because they challenged the power of the budding medical community. If you heal and do not practice medicine, then you must be working for the Devil. If you do magick for the Church, it is a miracle. If you do not work for the Church, it is the work of the Devil, which became synonymous with witchcraft. The hysteria of witchcraft was a convenient way to get rid of those with their own personal power and strong opinions in the society, as well as the elderly who were perceived as burdens to the struggling communities. The majority of the accused were not likely practitioners of witchcraft at all. At most, they had held on to folk magick. Townspeople would often accuse unwanted neighbors of practicing witchcraft in order to get rid of them.

The hysteria rose in fervor at this particular point in history because of economic downturns, poor social conditions, growing disease, and threats to the Church’s power base from religious sects and theological schisms. The main force of Europe, the Christian Church, may have been blamed for these conditions. This institution needed a scapegoat on the outside: blame these problems on the power of the evil witches.

Although not the first act of persecution, the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum served to fan the flames of these murders. This manual, called the Hammer of the Witches, or Witch’s Hammer, served as a supposed description of the witch’s practices, how to hunt them, capture them, and elicit confessions using tests and tortures that few people could ever hope to resist. None of the material was based on actual pagan practices, but on Christian doctrine and flights of the authors’ imagination and misogyny, although there is some speculation that the material was used by others as a manual to practice “witchcraft,” including the Black Mass, a mockery and corruption of the Catholic mass. Here are the roots of Satanism, not witchcraft. Contemporary witches see this form of “Satanic witchcraft” as having nothing to do with the true spiritual roots of the craft. The practices of witches, from various cultures to the Anglo-Saxon roots of the word Wicca, predated Christianity. To believe in the Devil, one must first believe in the tenets of Christianity. The Devil held no place in the pre-Christian pagan myths because ancient pagans did not recognize a source of ultimate evil. They recognized the forces of creation manifested in nature. Modern traditions of Satanism vary greatly, from those inspired by bad horror movies to those with sophisticated magickal philosophies. Some call themselves Satanists, but don’t even believe in an entity named Satan. These Satanist and Satanic witches have nothing to do with the healing roots of pagan witchcraft. All types of people claim to be witches, but not all of them claim the same beliefs and history.

For safety’s sake, anyone connected to the ancient pagan practices and arts of folk magick went underground with the knowledge, sharing it with a few, and passing it along family lines, because blood relatives were the only people who could be trusted. For ease of disguise, practices were cloaked in everyday actions and household tools. The broom, the knife, the spoon, and the cauldron all made their way into the magickal arts. Everyone had these objects, so you could not be accused of witchcraft for simply owning them.

Witches were not the only ones persecuted at this time. Anyone practicing a faith or lifestyle in a different manner was persecuted. Homosexuals were persecuted along with witches. The derogatory term “flaming faggot,” which refers to a gay person, originated in the Burning Times, citing execution through fire. The word faggot originally referred to kindling.

In 1492, Spain forced all Jews to choose between leaving the country, converting to Christianity, or execution. Some left, while others converted or seemingly appeared to convert. The Jewish people are the keepers of the Kabalah, a system of mysticism and magick. They found allies among the countryside witches, and possibly shared magickal secrets. Modern practitioners of the Kabalah greatly influenced the re-emergence of Wicca in the twentieth century.

Pope Alexander proclaimed an Act against witchcraft in 1502, followed by similar measures by Henry VIII in 1542 and Elizabeth I in 1563. Various laws and proclamations were passed in Europe and England throughout the time of persecution. Witch hunts in England and subsequently in America focused less on the antireligious act of heresy and more on the civil crime of witchcraft. The material of the Malleus Maleficarum was later absorbed by the Protestant witch hunters in England, but the country had ample material from their own demonologists. Matthew Hopkins proclaimed himself Witch Finder General in England, inspiring many other witch hunters. Some speculate that witches migrated to the American colonies to escape persecution, but the hysteria soon followed in the form of the infamous Salem witchcraft trials.

In Salem, Massachusetts, now a neopagan mecca, a hysteria of witchcraft led by the accusations of a few teenage girls fascinated with the occult lead to the death of thirty-six people and the imprisonment of over 150 men and women in this Puritan community in 1692–93. This episode in America’s history is considered part of the Burning Times, but no one was burned at the stake in Salem. Many were hung on Gallows Hill, and present-day pagan community members of Salem, Massachusetts, celebrate rituals on the site believed to be Gallows Hill, to remember those who died in the name of witchcraft. Most likely the victims of the Salem trials did not practice witchcraft, but were targets of malice by their accusers. Although a few subsequent witchcraft trials took place in America after the end of the Salem trials in 1693, none yielded an execution. The end of the hysteria was a turning point for the Burning Times. The transformation to capitalism, the Industrial Revolution, advances in science, and a general social criticism and disgust for the tortures in this newly evolving modern world helped end such unfounded hysteria.

1972 c.e. U.S. IRS recognizes witchcraft as a religion and grants tax-exempt status to the Church and School of Wicca.

1966 c.e. Goddess-oriented archeological discoveries from the Neolithic period.

1954 c.e. Witchcraft Today by Gerald Gardner is published.

1953 c.e. Gardner forms his own coven.

1951 c.e. England’s Witchcraft Act is repealed.

1939 c.e. Gerald Gardner initiated into witchcraft.

1921 c.e. The Witch Cult in Western Europe by Dr. Margaret Murray is published.

1899 c.e. Aradia: Gospel of the Witches by Charles Godfrey Leland is published.

1898 c.e. Aleister Crowley joins Golden Dawn.

1890 c.e. Sir James George Frazer publishes The Golden Bough.

1888 c.e. Founding of the Golden Dawn.

1875 c.e. Founding of the Theosophical Society.

1834 c.e. Suppression of the Spanish Inquisition.

1735 c.e. King George’s Witchcraft Act of 1735.

1693 c.e. Salem witchcraft trials end.

1692 c.e. Salem, Massachusetts witchcraft trials begin.

1645 c.e. Matthew Hopkins proclaims himself Witch Finder General.

1563 c.e. Elizabeth I’s Act Against Witchcraft.

1542 c.e. Henry the VIII’s Act Against Witchcraft.

1502 c.e. Pope Alexander’s Act Against Witchcraft.

1492 c.e. Spain forces Jews to convert to Christianity.

1486 c.e. Publication of Malleus Maleficarum.

1478 c.e. Beginning of the Spanish Inquisition.

1400 c.e. Approximate start of the Burning Times.

1313 c.e. Supposed birth of Aradia, daughter of Diana.

1231 c.e. Beginning of the medieval Inquisition.

800 c.e. Holy Roman Empire is founded.

500 c.e. Romans leave British Isles.

476 c.e. General date for the fall of the Roman Empire.

447 c.e. The Council of Toledo defines the Devil as the embodiment of evil.

313 c.e. Edict of Milan.

4 b.c.e.–29 c.e. Supposed lifetime of Jesus of Nazareth.

27 b.c.e. Founding of the Roman Empire.

200 b.c.e. First clashes between Romans and Teutons.

390 b.c.e. Celts invade and plunder Rome.

500 b.c.e. Celts go to Britain.

1200 b.c.e. Celtic culture in what is now France and West Germany.

1500 b.c.e. Approximate building date of Stonehenge.

2200 b.c.e.–14,000 b.c.e. Minoan period of the Aegean civilization.

2630 b.c.e.–1530 b.c.e. Egyptians start building pyramids.

3500 b.c.e. Start of Egypt’s Old Kingdom.

3600 b.c.e. “Civilization” begins in Sumeria.

8000 b.c.e.–1500 b.c.e. Neolithic period (approximate).

13,000 b.c.e.–8000 b.c.e. Mesolithic period (approximate).

2,500,000 b.c.e.–13,000 b.c.e. Paleolithic period (approximate).

The Modern World

England passed the Witchcraft Act of 1735 under the power of King George I. This legislation basically stated that witchcraft was not real and all persecutions should cease. It did allow persecution of those who pretended to possess supernatural powers. Although the general populace still saw witches as evil monsters making deals with the Devil, the notion eventually subsided into the deeper parts of our collective consciousness. In several places, the wise ones and cunning folk quietly began working again as healers.

Although the Age of Reason prevailed in most of society, a resurgence in the esoteric was bubbling beneath the surface. Various spiritualist movements swept over the Western world, particularly in Britain and America, starting around 1850. Such a movement piqued interest and thought on reincarnation, psychic abilities, and healing. Séances became quite popular. For some it was entertainment, a spectacle to partake in, but for many it was the birthing of a new religion, one that was often dogged with accusations of trickery and fraud. In some ways, this was the first breath of the modern New Age movement, which was really bringing older concepts of spirituality to the modern world. Individual stars rose to shine the light of the New Age on the world, and are honored for their contributions, which are still accompanied by the controversy of their day.

H. P. Blavatsky, a Russian émigré to England, brought many concepts of Eastern mysticism to the West, and also revived the knowledge of the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, including Hermetic philosophy. She cofounded the Theosophical Society in 1875, a group dedicated to teaching the ancient mysteries of spiritual wisdom. Blavatsky believed that all religions sprang from the same source of spiritual wisdom, and that she was guided by hidden masters, ascended beings, to found the organization. She is best known for her works Isis Unveiled and The Secret Doctrine.

In the late nineteenth century, England was a hotbed of occult activity. One of the most influential and well-known groups was the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. The order was founded in 1888 by the occultist Samuel Liddel MacGregor Mathers with Dr. William Westcott and Dr. William Robert Woodman, both master Masons and members of the Rosicrucian Society of England. The material was based on a supposed ancient manuscript found by Rev. A. F. A. Woodruff, a Mason and member of the Hermetic Society who consulted with these men on the nature of the manuscript. The Golden Dawn studied and taught ritual magick, the Kabalah, tarot, psychic abilities, scrying, alchemy, and astrology, most likely drawing from Rosicrucianism and Masonry. The group had many internal conflicts and splinter groups. Famous members include Arthur Edward Waite, William Butler Yeats, and Aleister Crowley, who continued to pioneer magick and exert a strong influence on the newly emerging craft of Wicca.

Of all the modern magicians, Crowley was considered the most infamous, and much of his reputation as “the wickedest man in the world” was well deserved. His life is a story of excess and ego, but also one of a brilliant magician. As a young man, he joined the Order of the Golden Dawn in 1898. Crowley was a student of Mathers, but their constant quarrels ended that relationship. After leaving the Golden Dawn, Crowley was the eventual leader of the OTO, or Ordo Templi Orientis. Through a series of messages from a spirit named Aiwass, Crowley founded the Thelemic Mysteries. This unusual man saw himself as the prophet of the next great age, the Age of Horus, and often referred to himself as the “Beast of the Apocalypse.” His most notable works include The Book of the Law, Magick in Theory and Practice, Magick Without Tears, The Book of Thoth, Moonchild, and Diary of a Drug Fiend.

In 1892, Charles Godfrey Leland, an American author and scholar, published Etruscan Roman Remains. The work was based on his study and research of Italian witchcraft, as researched while he lived there, having moved to Italy in 1880. His previous magickal work included research into the Gypsy culture and its magickal systems. In fact, he was the founder of the Gypsy Lore Society. This work set out to prove that not only was there a tradition of witchcraft that could be traced back to Italy, but that the craft was still practiced there presently, worshipping the goddess Diana. Although not stated outright, his work implies study with these Italian witches and possibly initiation into the craft. One witch in particular, identified as Maddalena, gathered folklore, poems, stories, and rituals for his research. The material gathered eventually became another book, Aradia: Gospel of the Witches, printed in 1899, and it is for this work that he is best known in the neopagan communities. Aradia detailed stories, rituals, and philosophy from a woman living in the Middle Ages, supposedly born in 1313, named Aradia. Some see her as an avatar of the goddess Diana. Witches liken her to a Jesus Christ or Buddha figure. She came to enlighten the peasants of Italy with teachings of magick and empowerment. Inquisitors’ records from this age indicate references to an increase of witchcraft in Italy.

The unusual and often off-putting tone of Aradia’s Gospel is surprising because previous works by Leland, including Etruscan Magic & Occult Remedies and Legends of Florence, present a view of witches as misunderstood followers of the Goddess. The Gospel shows a tendency toward the Christian stereotype of witches, including material regarding Lucifer and strong anti-Christian sentiment. Although genuine material appears mixed with the Gospel of Aradia, since most of it is based on Maddalena’s material, scholars wonder why the sudden change. Was this tone from Maddalena playing Leland for a fool, or purposely veiling the information so that it would not be taken seriously? Perhaps the surviving witches adopted ideas from the Inquisition, as the oral traditions broke down. Since Leland died before he completed his next work on the subject, we may never know.

In 1890, Sir James George Frazer published The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Frazer was a member of Leland’s Gypsy Lore Society and a respected British anthropologist. The Golden Bough delved into the mysteries of ancient paganism, particularly in Italy, and strongly emphasized the concept of the Divine King found in many areas of Western magick and religion.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, Edgar Cayce, the now-famous “sleeping prophet,” began to give psychic readings. This man had no medical background, but gave very detailed accounts of medical illness and procedures to cure such illnesses. Later readings involved the concepts of karma, spiritual roots of disease, prophecy, and the fabled continents of Atlantis and Lemuria, echoing the work of Blavatsky, though Cayce was a devout Christian. The Christian flavor of his readings might not be tied directly to the witchcraft revival, but he introduced many people to such occult concepts as nontraditional healing and psychic powers. Several organizations sprung up around his groundbreaking work.

Psychiatrist Carl Jung played an important role in the modern mystical revival. Although a contemporary and student of Freud, C. G. Jung’s work was inspired by his own psychic experiences. He paved the way for a scientific, analytical look at the mystic’s world, investigating the interpretation of dreams, symbols, mythology, I Ching, tarot, the collective consciousness, synchronicity, and archetypes. His interest in ancient alchemy and Gnosticism, from a psychological approach, revived interest in both subjects. His work was first published in the early 1900s, and his material was still being released after his death in 1961. Many current mystics who have difficulty with literal interpretations of ancient wisdom seek the work of Jung to give the modern conscious mind an easily understood reference point.

The Witchcraft Renaissance

In 1951, England repealed the Witchcraft Act. Believing witchcraft to be a superstition, laws against it seemed to perpetuate the ignorance of believing in such illogical things as magick. The scientific and social revolutions were supposed to have squelched belief in spells and witches. In reality, the repeal had quite the opposite effect, and began what is affectionately referred to as the Witchcraft Renaissance.

At the forefront in the new movement of witchcraft was Gerald B. Gardner, a British civil servant who spent some time in Malaysia exploring Eastern mysticism. He was fascinated by the occult and influenced by the work of Margaret Murray, author of The Witch Cult in Western Europe, published in 1921. She claimed that the witches persecuted in Europe were practitioners of an ancient religion of European fertility cults based in goddess worship. Her theories were influenced greatly by her own personal beliefs, since scholars cannot find evidence to this link as an organized religion. Murray was correct in the fact that the wise ones were the spiritual descendants of the ancient goddess cults and mystery traditions, if not physically linked.

Gardner claimed he was initiated in 1939 into a long-standing coven of hereditary witches practicing the craft in New Forest. This group taught him the “Old Religion” as a magickal art and a personal religion. Based on their research with Gardner’s contemporaries, Janet Farrar and Gavin Bone, co-authors of The Healing Craft, with the late Stewart Farrar, believe this New Forest “coven” was actually a group of Theosophists. In Gardner’s day, anyone involved in the occult was considered a “witch.” Gardner formed his own coven in 1953, borrowing and adapting material from the New Forest group and other occult sources. Gardner drew from his previous experience as a Freemason, his time in Malaysia, and his passing acquaintance with Aleister Crowley. Rumor has it that Aleister Crowley actually wrote Gardner’s first Book of Shadows, but that is unlikely. More likely, Gardner was probably inspired by much of Crowley’s work. Like the forefathers of the modern mystical movements, Gerald was followed by much controversy. Opinions of his character and work varied greatly. He claimed to be re-introducing an ancient religion, but the general consensus is that much of the material is his own invention. Such facts do not take away from the contemporary practice. All religions change over time and go through many birthing periods. The modern movement of Wicca is no different.

Gardner initiated Doreen Valiente, who reworked many rituals in favor of her own Goddess-oriented approach. Valiente was instrumental in shaping the new movement, and this specific tradition was named Gardnerian Witchcraft, after Gerald Gardner. Their original Book of Shadows has been copied from, added to, and adapted by a long line of modern witches.

Clearly Valiente and Gardner were inspired by the work of Leland and Aradia: Gospel of the Witches. The “Charge of the Goddess” is often attributed to Valiente, but the original version of the Charge comes from Aradia. Leland actually writes on many of the same topics as Gardner, in reference to the Italian traditions of the Strega, or witch, instead of the Celtic mysteries. The Roman occupation of the British Isles could have spread such concepts to the Celtic people, becoming mingled with their own magick. In fact, Gardner spent some time in Italy prior to his publication, where he studied Roman paganism and remarked how the artwork at Pompeii depicted the mysteries found in witchcraft. The art of the witch can be traced to many cultures, not just one. The world owns the tradition of witchcraft, and all are welcome to it.

In 1954, Witchcraft Today by Gerald Gardner was published, soon followed by The Meaning of Witchcraft in 1959. His writing drew considerable attention, coming on the heels of Robert Graves’ influential yet disputed work The White Goddess. These works were fueled by a general desire in some of the population for a personal spiritual path. Regardless of the origins of the material, Gardner is credited as a spiritual forefather. The Witchcraft Renaissance blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s, inspiring covens in Europe, the United States, and Australia. Gardner is considered the modern founder of Wicca, and his work is one of the reasons why the craft has spread so far and wide.

While Gardner was busy cultivating his brand of the Old Religion, other forms sprang up elsewhere. Since witchcraft was no longer considered a crime in Britain, other hereditary traditions made themselves known, like Gardner’s New Forest coven. They, too, claimed descent from more ancient traditions, kept alive in secret during the Burning Times. Though I do believe in the possibility of many such covens scattered about Europe and even America, I think they are far rarer than most would have you believe. Folk magick has been practiced in many families that were not unbroken lines of witches. My family practiced magick with my grandmother’s generation, but they were also staunch Catholics. The Goddess survived in the form of Mother Mary, but none of my more recent ancestors would have claimed the title “witch.”

Others took Gardner’s foundation and built new traditions, reflecting their personal tastes. The most famous is Alex Sanders, the self-proclaimed “King of the Witches.” Sanders was already familiar with ritual magick and claimed to be initiated into a family tradition by his grandmother when he was seven, after he stumbled upon her in ritual. His tradition is known as Alexandrian Witchcraft, although it bears a close resemblance to Gardner’s.

In other groups, the word witch was stripped away, focusing on the pagan elements, founding the neopagan movement. Somewhat divorced from Wicca, these were the foundations of our modern Earth-based religions. Keen interest in Native American mysticism and shamanism developed as part of the New Age movement. Since these shamans were never persecuted by their own people, their traditions survived and were thought to be somewhat similar to the practices of ancient tribal witches. Native people began a period of openness in sharing this material, though some objected. While Native American spirituality seems safe and honorable to the mainstream public, those same people often view witchcraft with the stigma of evil perpetuated during the Burning Times. Witches often point out the fundamental similarities between Native American practices and those of the witch.

Women dissatisfied with the roles of traditional religions flocked to the goddess religions, creating feminist branches of Wicca, including Dianic covens. Archeological discoveries of a goddess culture in Anatolia from the Neolithic period, at Catal Juyuk, Mersin, and Hacilar, were published in 1966. This new evidence of the ancient world coincided with the rising feminist movement in the West during the late sixties. Both contributed to the growing awareness of the Goddess in the Western mind. Feminine roles were changing and awareness grew. The discovery of a matriarchal culture valuing feminine ideals and spirit was a wake-up call to the end of the patriarchal age, dominated by masculine deities and customs. History revealed a forgotten part of the world’s past. Those involved in neopaganism and neo-witchcraft sought the divine in both the Goddess and the God, honoring masculine and feminine.

In 1972, witchcraft was granted the status of a legally recognized religion in America when the IRS granted the Church of Wicca tax-exempt status. Witchcraft is now protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments in the United States. Ordained priests and priestesses enjoy all the same rights as traditional clergy.

The traditions and movements have branched out many times, forming a complex web including almost as many traditions as practitioners, creating an eclectic mix. Witchcraft is very personal, and you can no longer really say there is a “right” way and a “wrong” way to practice it.

The branches of the witchcraft tree continue to grow up and out, forming a deliciously complicated pattern. Everyone has an opinion on where it has been, where it is now, and where it is growing, but such facts seem fluid, never completely defined or documented, as are the mysteries of witchcraft itself. Like the roots of our history, the branches of our future are heading in many directions at once, exploring new territory and reaching to greater heights.

Recommended Reading

When God Was a Woman by Merlin Stone (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich).

Origins of Modern Witchcraft: The Evolution of a World Religion by Ann Moura (Llewellyn Publications).