Lesson 3

The Magick of Science

At one time, science and spirit were a single discipline, but the two broke apart in Western culture, and did not mix again until the twentieth century. The twentieth century is looked at as a time of dispelling the occult and paranormal, but science, strangely enough, has led us back to the mystical through some interesting theories and the advent of a new paradigm that borders on the spiritual, and not the mechanical. The threads of many different disciplines lead to the view of the universe as a holistic system. One of the first was the somewhat controversial theory of quantum physics.

The basis of quantum physics began in several stages in the early 1900s, and is attributed to the contributions of six men: Niels Bohr, Paul Dirac, Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, Max Planck, and Erwin Schrödinger. Originally the theories were not an attempt to create a new discipline or scientific paradigm, but to account for odd experimental results that did not conform to the generally accepted classical rules of physics.

Though a quanta refers to a bundle of energy, the smallest discrete amount of energy that can be measured, quantum theory does not deal exclusively with the microworld, but the entire universe. The previous scientific paradigm described the universe in terms of distinct divisions, and in particular two separate groups, particles and waves. Particles held a position and waves had momentum. The building blocks of all matter and energy were either in particle or wave form. Everything was believed to be separate and distinct; every part is in its own space and time, linked only through observable forces. Classical physics is very rigid and predictable. Events happen due to an observable cause and effect. Conditions can be maintained and controlled in experiments to repeat the process with the same results.

However, results of many new experiments with subatomic particles did not fit this classical model. Some results were “nonlocal,” occurring without an observable cause. The further one dove into the microworld, and divided the particles of matter into smaller and smaller units, the less they behaved like individual units. The distinction between particles and waves grew fuzzy. At times, a unit such as an electron behaved as a particle. We think of an electron as a ball of energy with a negative charge, circling the nucleus of an atom, like a planet orbiting the Sun. In other experiments, an electron exhibited the characteristics of a wave. It depended on the experiment. In fact, it is speculated that such energies only have a particle form when we are looking at them. It is like saying that the universe changes when we turn our back on it, but then conforms to our expectations when we observe it. We can never know both the position (particle) and the momentum (wave) of a quanta at the same time. Observing one changes the other. In fact, they may not possess both attributes at the same time. This is the core of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. Suddenly the particles of matter, which we thought were solid and dependable, became fuzzy and nondescript. Certain energies, such as x-rays, were always believed to be in wave form, but under certain conditions, they exhibited particle properties. Suddenly everything we knew about physics was called into question.

Scientists discovered the power of the observer. Somehow the interaction of the observer, once considered independent of the experiment, had become crucial to the way experiments were conducted, and the results were subtly influenced. The behavior of the phenomenon would change, depending on who was observing it and what thoughts, feelings, and expectations the observer had. Controlled conditions were no longer “controlled.” Gradually scientists started coming to the conclusion that the “pieces” of an experiment were not separate unto themselves, but part of a larger whole, extending beyond the experiment and including the observer and quite possibly the whole universe.

Leading us in a similar direction, but from a completely different route, was the neurosurgeon Karl Pribram and his work with the brain, memories, and vision, starting in the 1940s. Until then, scientists believed that specific memories were located in specific regions of the brain. Through research with animals and people with specific portions of their brain removed, he discovered, along with his mentor Karl Lashley, that the individuals did not suffer specific memory loss, coming to the conclusion that memories were not held in specific areas, but nonlocally, throughout the brain. The mechanism allowing the brain to accomplish such a feat was unknown to him until he discovered the model of the hologram.

The Hologram

The hologram plays an important role in understanding these new scientific advances, so let’s discuss it in detail. A hologram is a three-dimensional sculpture of light. It is a recorded image, like a photograph, but a photograph is flat, with only two dimensions. The hologram is three-dimensional. You can look at it from any angle, and it looks real, with depth and texture. If you try to touch it, you realize it is not solid, but a construct of light.

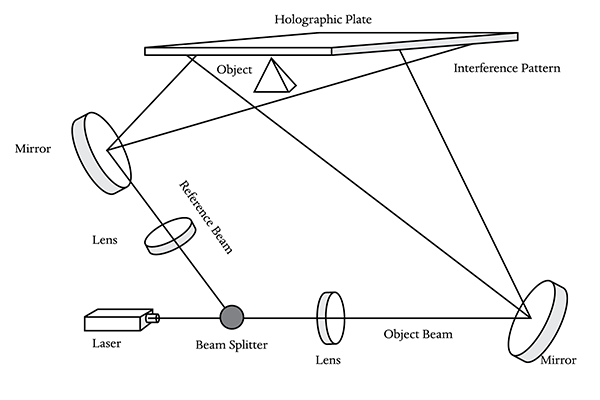

The hologram is created through the use of a special form of light, a beam of coherent light called a laser. A laser beam is split through the use of a device called a beam splitter. One beam is bounced off the object to be recorded. The second is directed with mirrors until it collides with the reflected light of the first. These two beams create an interference pattern, two patterns overlapping (Figure 8A).

Any two waves can create an interference pattern, but those of the laser beam are special. To understand an interference pattern, think of a pond. When you drop a pebble into the pond, it creates rings moving outward. When you drop two or more pebbles, the rings cross each other, creating an interference pattern.

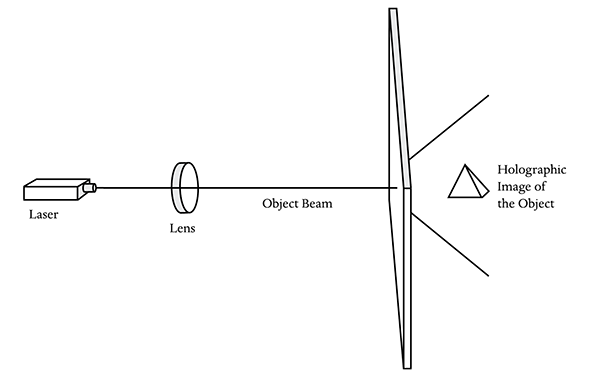

The resulting interference pattern from the lasers is recorded on a special film, called a holographic plate. The pattern itself looks nothing like the object. Upon close inspection, it looks somewhat similar to the waves in the pond. But when you shine a laser through the holographic film, it creates a three-dimensional image of light, a hologram, of the object (Figure 8B).

The most interesting property of the hologram is the pattern. Each piece of the film contains all the information of the pattern. If you rip the holographic film into two pieces, and shine a light into one, you get the whole image, only smaller. You can divide the film again and again, until you reach the limits of the technology, but theoretically, the pattern can continue to be reduced and still contain the image. The film will deteriorate the image at a certain point.

The main points to remember about holograms are that the pattern created from two beams of energy can store three-dimensional information, and that the storage is nonlocal, meaning each piece of the pattern contains all the information necessary to recreate the image.

The holographic model of the brain, in which each part contains the whole, provides an interesting answer to the way the brain receives information, retrieves memory, and creates our point of view. Since our memories are recorded holographically, brain damage does not necessarily remove specific memories or even functions. The brain can “trick” us into thinking that our internal processes are external. We cut our hand and feel the pain in our hand, but the pain is actually caused through a chemical reaction in their brain. The sensation of “phantom limbs” to people missing them could simply be a holographic memory of those limbs, as recorded in the interference pattern of our brain. The memory accidentally gets played back, feeling very real, but has no basis in physical reality.

Taken further to its logical conclusion, Pribram opened a door to a whole new world, where our perceived outer reality is actually occurring internally. The world may not be as solid as we think, but perceived by the brain in holographic terms. The world only becomes familiar as it enters our senses, but in actuality, the world is an interference pattern.

Fields of Consciousness

In 1952 on the isolated Island of Koshima, scientists were observing the behavior of Japanese monkeys (Macaca fuscata) by giving them sweet potatoes dropped in the sand. They liked the potatoes, but disliked the sand clinging to them. One female monkey solved this dilemma by washing the potato, and subsequently taught her mother and friends. Soon potato washing became a cultural trend and many learned to wash. From 1952 to 1958, all the new young monkeys practiced washing, while some of the older ones held to the older practice of eating them dirty. That fall, the scientists noted something very strange. Once a certain critical mass was reached on Koshima, and all monkeys of the Macaca fuscata species on that island started washing their potatoes, monkeys on other islands, separated by water, also began to wash their potatoes. These monkeys were not taught this skill, but somehow knew. No information was transferred on any recordable level. The practice came into the general consciousness of the monkeys.

Though not a controlled experiment, this lead to the postulation that a species is connected by some invisible field of consciousness. When a small number of the species, in comparison to the entire population, learn new information or a way of life, it remains their individual knowledge. When a critical mass of those with the knowledge is reached—in this case it was speculated to be one hundred—the information becomes part of the race’s consciousness, available to all. The story of the Japanese monkeys is told by Lyall Watson in the book Lifetide, but other experiments have been conducted since, with animals and even people.

The hundredth monkey theory supports the concept of morphogenetic fields, whose main proponent is Rupert Sheldrake. Sheldrake, a pioneer in the biological sciences, built on the work of Hans Spemann, Alexander Gurwitsch, and Paul Weiss, who in the 1920s each independently proposed that morphogenesis, the coming into being of form, is organized by fields of energy. Sheldrake developed his morphic field theories, influenced by Hindu spirituality, Sufism, and Goethe. This theory proposes that each species creates a field with low energy, but with vast amounts of information, acting as a cumulative collective memory for that type of organism. The morphic fields include information on the genetic, behavioral, social, cultural, and mental levels. This would certainly include the information transferred through the hundredth monkey theory and go far beyond it. Such fields cannot be seen or measured, and move across space and time, but directly influence the development of a species, built up from the life of all beings in said species. These fields, too, are nonlocal. Physically, they act as a geometric influence, a template or blueprint for development. DNA acts as a resonator, or antenna, to pick up the influence of the field. Each species’ DNA “tunes in” to the appropriate species field.

We can tune in to the information of the morphic fields, not only for physical development, but for any information in our species. Our brains and memories retrieve information from the field when needed. Although we contain individual identity, characteristics, and knowledge, we also share in the wealth of identity, characteristics, and knowledge of our species.

On the spiritual front, morphic fields could be pointing the way to consciousness beyond the physical, and we can speculate about the existence of nonphysical beings, ghosts, angels, goddesses, and places such as heaven or the Underworld as part of these nonphysical information fields. C. G. Jung’s collective consciousness could be one aspect of these energy fields being explored by science.

The Holographic Universe

The last piece of the puzzle was delivered by a quantum physicist named David Bohm. Our brain researcher, Pribram, actually discovered Bohm’s work on the advice of his own physicist son. Bohm started studying quantum physics in the 1930s and was fascinated by the interconnected aspect between subatomic particles, though most other scientists gave it little recognition. Through his experiences teaching, writing, and researching, he became dissatisfied with the theories of quantum mechanics and searched for greater understanding. Through various experiences, including exchanges with Albert Einstein, who was also unhappy with the direction of quantum physics, he came to the conclusion that the universe behaved as a vast and complex hologram. Through his study of the degrees of order, he became focused on the fact that beneath our physical reality, what he called the explicate (unfolded) order, was the hidden world of the truer reality, the implicate (enfolded) order. The implicate order is like the holographic film, an interference pattern. When the correct light is shined through it, the implicate order creates the explicate order that we are familiar with. Our perception of objects, and the entire world, is caused by countless unfoldings and enfoldings between the two orders. Bohm published these theories in the early 1970s and then most comprehensively in 1980 in the book Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Although many in the scientific world agree with his findings, the holographic universe theory remains controversial.

The philosophical implications of the holographic universe are vast. Our comfortable reality is an illusion created by patterns of energy interacting with our senses, our consciousness. Mystics from the East always called the world the maya, meaning “illusion.” Our separateness is an illusion, our oneness the truth. The hologram, where all fragments contain the whole, seems to be the ideal model for this—the witches’—view of the universe. Nonlocal energy fields, extending across time and space, influence us all the time. Our brains, or more importantly, our minds, behave like miniature universes, if a sense of size can even be applied. Nothing is completely individual or isolated, existing in a vacuum. All things are connected. The observer is the observed. We, and the entire world, are all constructs of light, holograms, believing we are solid because we are in the hologram of the universe. We are really energy. Matter, time, and space are all forms of energy.

To the witch, to the mystic, this is no surprise at all, though the words and symbols are new. The underlying principle of spirituality is the connection between all things. Even as we create new models and paradigms to replace quantum physics, holograms, and morphic fields, they continue the general trend of wholeness. Modern research into fractals, infinitely complex patterns that exhibit repeated patterns under greater magnification, and superstring theory, the theory expanding the universe beyond three dimensions of space, follow in the footsteps of describing a vast and complex, yet whole, universe. Ancient myths often speak of a weaver goddess, weaving the universe into form. Perhaps she weaves with “superstrings.” These stories, including scientific theory, explain what we know in our spirits.

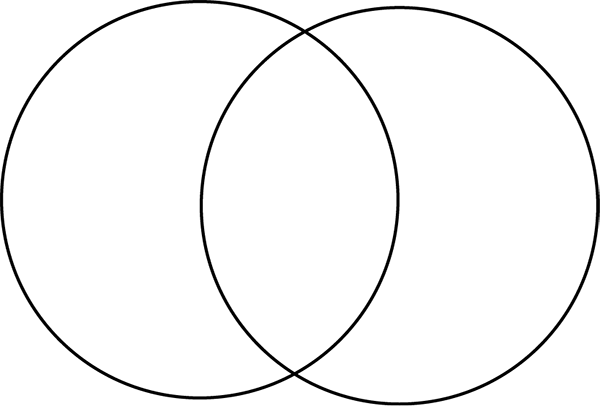

The most primitive model of the hologram, two systems creating a third, an interference pattern, is the image of the Vesica Pisces (figure 9). The Vesica Pisces is two circles overlapping to create an “eye” or “fish” shape, often drawn alone as a popular Christian symbol. In sacred geometry, the spiritual study of shape and its role in creation, the Vesica Pisces is called the Eye of God, and through it all things are created. The two forces, or polarities as we will later learn, can be viewed as anything: black/white, light/dark, creation/destruction, or chaos/order. Many would say good/evil, but witches see the Goddess and the God as the two patterns of creation. Their love brings about the third pattern, our reality. Our reality is the “eye” of the Vesica Pisces.

Perhaps the ancients understood the hologram far better than we give them credit for, and we are just rediscovering the spiritual wisdom that we had cast aside because we did not understand.

Continuing Assignments

• Daily journal—Write three pages a day.

• Honor and recognize your intuition. Continue to ask it questions.

• Practice the orange meditation.

• Use instant magick in your daily life.

Recommended Reading

The Holographic Universe by Michael Talbot (HarperCollins).

Stalking the Wild Pendulum: On the Mechanics of Consciousness by Itzhak Bentov (Destiny Books).

The Tao of Physics by Fritja Capra (Bantam Books).