Flooded with sunlight, the landscape of the Nile Valley is a network of irrigation canals interwoven with a many-colored mosaic of fields, villages, gardens, and palm groves. The area around the village of Mit Rahina, not far from the famous Step Pyramid at Saqqara, is no exception. At first sight there is almost nothing to suggest that it was here, almost within sight of the high-rise buildings of Cairo, which encroach ever campaigns to the Western Asia. It was a city which, at the height of its prosperity, extended over an area of approximately 50 square kilometers, but which then vanished almost without trace. The efforts of the archaeologists who have been attempting to unearth its secrets since the beginning of the last century resemble in some ways the proverbial drop in the ocean but have nevertheless continued to bring us new discoveries and new knowledge. The history of the magnificent city has not been lost forever.

Meni, the legendary unifier of Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty, who is credited with the founding of Memphis, could scarcely have chosen a more suitable site on which to build an administrative center for the newly established state. He selected a place on the southern bank of the Nile near the point at which the river valley spreads out into its delta. Just a few kilometers to the north, the Nile, whose course has shifted three kilometers east over the last five thousand years, divides into the branches that determine the basic shape of the Delta. To the east and west the narrow, rocky banked valley, is surrounded by the immense desert. The city which Meni founded was called Ineb(u) hedj, “The White Wall(s),” perhaps because the ramparts of the stronghold which at the same time served as the royal residence, were white. The precise site of this historic center of Memphis has not yet been located with any certainty, although the latest British archaeological researches, using deep-hole drilling, have indicated that it could lie under the northern part of the present-day village of Mit Rahina. At any rate, the remains of “the White Wall” and of later Memphis, lie under several meters of Nile mud.

The god Ptah, Lord of Memphis. Detail of sunk relief from the so-called Small Temple of Ptah of Ramesses II. Kom al-Rabia’a, Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

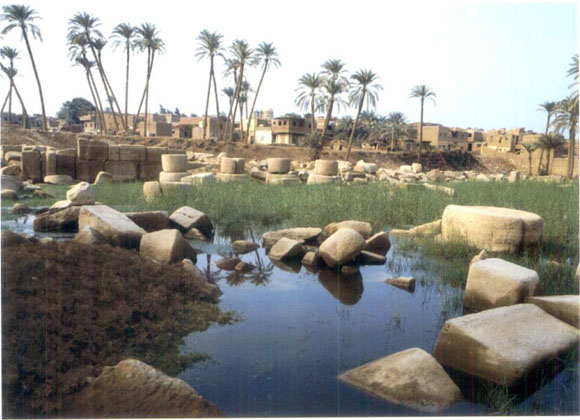

Ruins of the Columned Hall of the Temple of Ptah, Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

It is believed that, in addition to the stronghold, Meni also founded a temple of Ptah, the chief god of the new royal seat. Judging by Ptah’s epithet “who-is-south-of-his-wall,” the temple was probably built south of the stronghold “White Wall(s).” Some archaeological finds indicate that the remnants of the early Temple of Ptah may lay under the houses built on a hillock called Kom al-Fakhry. The temple, which gradually became one of the greatest in the land, was called Hutkaptah, “The Temple of the Spirit of Ptah,” and in the later pronunciation Hikupta In its garbled and Graecized form it was the origin of the name Egypt itself. It seems that every Egyptian ruler considered it an obligation to extend and augment the Temple of Ptah with his own buildings, statues, obelisks and other features. As in the case of the Temple of Amon in Karnak, so in Memphis there gradually emerged an enormous temple complex of which only a small part has so far been uncovered and archaeologically investigated. For much information about the Temple of Ptah at Memphis we are indebted to the Greek historian Herodotus, who may have actually visited it in the mid-fifth century BCE. The ancient Egyptians regarded the god Ptah as the god-creator and the patron of craftsmen and artisans. Ptah with his wife, the lion goddess Sakhmet, and his son Nefertem, formed what is called the Divine Triad of Memphis. Later a complete Memphite religious doctrine developed which concerned the creation of the world on the basis of Ptah.

Plan of the parts of ancient Memphis so far archaeologically investigated.

1. Northern Enclosure;

2. Palace of Apries; Enclosure of Ptah;

4. Pylon and hypostyle hall;

5. Embalming house of Apis-bulls;

6. Tombs of high-priests of Memphis;

7. Temple of Ramesses II;

8. Temple of Hathor;

9. Colossus of Ramesses II;

10. Temple of Ramesses II;

11. Alabaster Sphinx (perhaps of Amenhotep II);

12. Palace of Merenptah.

A major contribution to the development of the Temple of Ptah was made by Ramesses II, from whose reign date a number of the parts of the building that have so far been uncovered. These include the hypostyle hall and the South Gate, on which colossal statues of the pharaoh once stood accompanied by other figures. Work on extending the Temple of Ptah proceeded into the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Besides Ptah and his triad, other deities were worshipped in Memphis, first among them being Hathor, the goddess of love and beauty and the guardian of the family. There were also non-Egyptian deities, whose cults were practiced by the numerous foreigners living in Memphis. One important Memphis deity was the sacred bull Apis, regarded as the earthly incarnation of the god Ptah. His temple has not yet been discovered, but a building in which embalming and mummification ceremonies were carried out on the sacred bulls has been found. Enormous alabaster embalming tables decorated with lion figures were found within it. The mummies of the sacred bulls were buried not far away, in North Saqqara, in the underground catacombs of the Serapeum, which was once linked with Memphis by means of an alley of sphinxes.

Alabaster embalming table. The so-called Embalming House of the Sacred Apis Bulls from the reign of Sheshonq I. Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

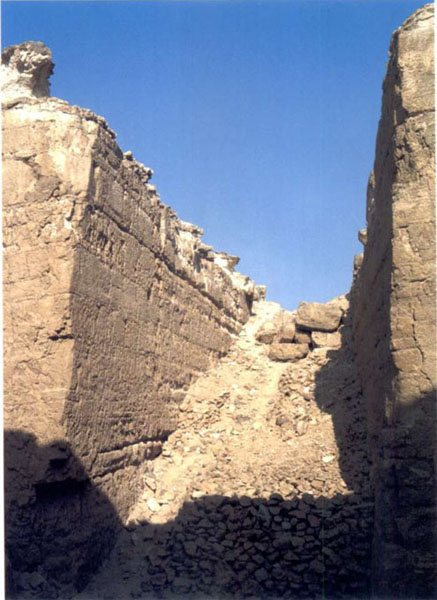

Ruins of the Palace of Apries from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

The district of the Temple of Ptah constituted the southern center of Memphis. A second center, a few kilometers to the north, was later formed around the district of the Palace of Apries. Apries, the Egyptian equivalent of the Greek name pronounced “Haaibre,” was a relatively powerful pharaoh of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty. He built a fort in Memphis that had a rectangular ground plan and a massive enclosure wall. He constructed a large palace at the northeast corner of the fort on a raised platform. The platform, the major part of the other buildings making up the Apries Palace, and the fort were all built out of mud bricks. It is possible that this building material, which at the time of the destruction of the monuments attracted less interest than did the various kinds of stone, contributed to the survival of the ruins of the Apries Palace, which were preserved up to a height of approximately ten meters. The mound of the Palace ruins is now the highest place in Memphis. Looking westward from the top of the mound the view is a unique panorama of the Memphite necropolis and the pyramids that dominate it.

From ancient Egyptian written material we know that Memphis was the capital of Egypt throughout the entire period of the Old Kingdom, i.e. almost to the end of the third millennium BCE. It was even, briefly (in the period after the collapse of Akhhaten’s experiment in reform) the capital in the New Kingdom. Even in the periods when it was not the capital city, Memphis maintained its status as an important administrative and religious center, especially for the northern and central parts of the country. It continued to be the biggest city in Egypt. Its fame only dwindled conclusively in the first centuries CE when the half-crumbled and deserted temples and palaces of Memphis were transformed into a large quarry from which building material could be obtained cheaply. After the occupation of Egypt by the army of Amr Ibn al-Aas in 641, the fortress of Fustat was built from the ruins of Memphis on the site of the fallen Byzantine stronghold Babylon, a place that was later to be the site of a new capital city: Cairo.

View of Kom al-Fakhry. The older part of the complex of the Temple of Ptah is believed to lie under this hill. Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

Research has made it possible to identify more than a hundred archaeological locations in the area covered by ancient Memphis. So far, the oldest antiquities uncovered are the remains of a residential area and artisans’ workshops dating from as early as the First Intermediate Period and beginning of the Middle Kingdom. They were discovered near Kom al-Fakhry. It has not proved possible to find monuments from the third millennium BCE yet, although there must once have been a very large number of these. The Old Kingdom, after all, which was the “era of the pyramid-builders,” was the age of the greatest flowering of Memphis.

The monuments, undoubtedly very diverse, were located at city sites which were often quite distant from one another. Attached to them were groups of administrative and residential buildings, which, despite their peripheral position, were very important. These grew up in the vicinity of the valley temples of the royal pyramid complexes on the edge of the desert. Some of these so-called “pyramid towns” temporarily acquired extraordinary importance. One example is the pyramid town near the valley temple of Teti, first ruler of the Sixth Dynasty, in North Saqqara. Insofar as its position was concerned it was just a suburb a few kilometers from the Temple of Ptah, but for a certain time during the first Intermediate Period it became the politico-administrative center of Egypt. Similarly, it is believed that at the end of the Sixth Dynasty and especially at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom, importance was acquired by that part of the capital which spread out to the environs of the valley temple of Pepi I, in what today is South Saqqara. The pyramid complex of Pepi I was called Men-nefer-Pepi, “The beauty of Pepi is enduring.” The shortened form of this name, Men-nefer Memphis” in Greek, began to be used to designate the whole capital city from the time of the Middle Kingdom. It is somehow fitting that it was a pyramid which gave the oldest of Egypt’s capital cities its name. The destiny of Memphis—its rise, flowering, and glory—was inextricably linked to the pyramids and the cemeteries lying at their feet. This relationship was aptly expressed by the Belgian Egyptologists Jean Capart and Marcelle Werbrouck when, in 1930, they entitled their book on the oldest capital of Egypt at the period of its greatest flowering, Memphis a l’ombre des pyramides—”Memphis in the Shadow of the Pyramids.”

Map showing the pyramid cemeteries of ancient Memphis.

The royal pyramid cemeteries of former Memphis lie like a string of pearls along the western edge of the Nile valley from the borders of today’s Cairo in the north right down to Meidum at the entrance to the Fayyum oasis in the south. Here, in the places where the sun set and where the limitless desert from which there was no return began, lay the land of the dead—the empire of the god Osiris. The reasons why the ancient Egyptians buried their dead on the edge of the desert on the western bank of the Nile are evident enough. The same, however, cannot be said of the reasons for their particular choice of sites for pyramid-building. Why, for example, did the founder of the Fourth Dynasty, Sneferu, build his first pyramid at Meidum and then abandon the place, building another two of his pyramids approximately 50 kilometers further north at Dahshur? Why did his son Khufu build his tomb, the celebrated Great Pyramid, still further to the north, in Giza? Why did the last ruler of the Fourth Dynasty, Shepseskaf, forsake the royal cemetery at Giza and, once again, select for his tomb a faraway site in a deserted spot at South Saqqara? The questions are numerous and, as a rule, answers to them remain on the level of conjecture.

Some Egyptologists believe that the choice of site for the construction of pyramids was determined by the very practical consideration of proximity to limestone quarries, since this type of stone was the basic building material. The limestone in question was the lower-quality limestone which was to be found on the western bank of the Nile and was used particularly for the so-called core of the pyramid, in contrast to the exterior casing for which it was necessary to transport fine white limestone all the way from the quarries in the hills of Moqattam on the opposite, eastern, bank of the Nile. There is certainly some force to this theory. After all, limestone quarries have been discovered near many pyramids. Nevertheless, limestone occurs almost everywhere in the area of the Memphite necropolis and the technical difficulties involved in obtaining it and transporting it to the building site did not vary substantially between the different places.

Hathor capital. Temple of the Goddess Hathor built by Ramesses II. Kom al-Rabia’a, Mit Rahina (photo: Milan Zemina).

There is an alternative and quite widespread opinion which was first expressed some time ago by the German Egyptologist Adolf Erman. In Erman’s view, a pyramid would be built in the vicinity of a pharaoh’s residence, the location of which could change. Although the offices of the highest organs of state, including the royal palace, were situated in Memphis, the rulers would build their other residences outside the capital city, often with a view to some pressing political, economic, or military interests. One particular variant, or addition, to the Erman theory is represented by the opinion that a ruler would deliberately build his palace near the building site of his pyramid with the aim of being present and personally participating in decisions on the serious organizational matters of the greatest and most important state project of his time—the building of the pyramid. Unfortunately, even in the case of Erman’s theory, we are dealing with pure conjecture, since so far we have not managed to discover and archaeologically investigate a single one of the royal residences of the Old Kingdom.

The Early Dynastic royal cemetery in North Saqqara is the oldest in the Memphite necropolis. The British Egyptologist Walter Brian Emery, who carried out excavations there for many years, believed that the first rulers of a united Egypt, whose seat Memphis had become, were interred in this cemetery. His view, however, did not make headway and the prevailing view among Egyptologists now is that the first rulers of a united Egypt, the pharaohs of the First Dynasty, were still being buried in the old royal cemetery of Upper Egypt at Abydos, at the place which natives of the region today call Umm al-Qaab, “Mother of Potsherds.” They believe that the tombs in the Early Dynastic cemetery in North Saqqara are either cenotaphs, false tombs constructed as a symbol of a ruler’s presence close to the new capital of the united Egypt, or, more probably, that they are the tombs of the highest state officials and members of the royal family who held posts in Memphis. The Early Dynastic tombs in Saqqara have the form of mastabas (from the Arabic—“mastaba,” an elongated rectangular clay bench) of large dimensions. They were built out of mud bricks and the outer surfaces of their walls, decorated with niches, were brightly painted to resemble the original model, which was of wooden poles and matting. The remains of rich burial equipment have been discovered in the underground chambers of several of these tombs.

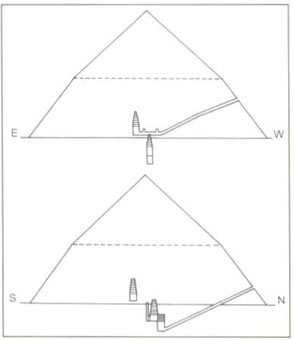

North–south section of the Step Pyramid (by J-Ph. Lauer).

The Step Pyramid. Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

The monumental gate of Djoser’s pyramid complex, Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

The tombs of the rulers of the Second Dynasty, which for the most part have not yet been discovered, represent one of the greatest problems of Egyptian archaeology. It is believed that the majority of these were located in the Saqqara cemetery near the Step Pyramid. Two enormous underground galleries discovered to the north of the Step Pyramid’s enclosure wall are considered to be the underground section of the tombs of the second Dynasty kings. The period during which this dynasty governed was unsettled and the stability of united Egypt was extremely fragile. There was probably even a breakdown in the unity of the country with consequent internal conflicts and the despoiling of the royal cemetery in Saqqara. Stabilization of conditions was only achieved by the last Second Dynasty ruler Khasekhemwy. His tomb lies in Abydos, but one of the two already mentioned underground galleries discovered south of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara is also attributed to him.

The beginning of the Third Dynasty brought a fundamental change in the design of royal tombs. As a result, the appearance of the royal cemeteries to the south of Memphis underwent a basic change. The founder of the dynasty, Netjerikhet, later called Djoser, built his tomb in the Saqqara cemetery not far from the underground galleries of his predecessors of the Second Dynasty. Originally the tomb took the form of a mastaba of relatively modest dimensions. In subsequent building phases, however, it was extended and remodeled as a six-stepped pyramid more than 60 meters in height and the first monument of its type. The architect of the Step Pyramid, as well as a a whole complex of other buildings of symbolic religious and cult significance, was Imhotep, who was probably Djoser’s son. Later generations venerated him as a sage and the son of the god Ptah. On an area 545 meters by 278 Imhotep created a symbolic residence for the dead king, from which rose the Step Pyramid—a gigantic stairway by which Djoser’s spirit would make its way heavenward. The whole complex of buildings, including a high enclosure wall, was built of shining white limestone. The pyramid could be seen from a great distance and was more than just a tomb: it was the visible expression of the pharaoh’s power. The Step Pyramid complex in Saqqara, which is considered the oldest work of monumental stone architecture in the world, became a great source of inspiration to Djoser’s successors. They too started to build their tombs in the form of pyramids. His immediate heirs, the rulers of the Third Dynasty, also built step pyramids. Djoser’s successor, Sekhemkhet, although he did not complete the task, began to build his tomb immediately next to the Step Pyramid. Also unfinished was the pyramid of Khaba, who abandoned the cemetery in Saqqara and chose for his pyramid a place only a few kilometers to the north and close to what is today the village of Zawiyet al-Aryan. The tombs of the remaining few rulers of the Third Dynasty have yet to be discovered.

The last pyramid to be designed and built in step form (except for the original plan of Neferirkare’s pyramid of the Fifth Dynasty at Abusir) lies approximately 60 kilometers to the east of Saqqara near the modern village of Meidum. The last ruler of the Third Dynasty, Huni, has sometimes been credited with initiating the building but archaeological finds have shown that it was the work of the Fourth Dynasty ruler Sneferu. Sneferu probably selected the site for the pyramid with a view to its strategic significance in the Nile valley near to the entrance to the Fayyum Oasis. The pyramid was built first in seven and later in eight steps. For reasons that are not quite clear (perhaps the retreat of the astral and the coming of the solar religion) it was decided to change it into what is called a true pyramid. Sneferu, however, was never buried in this pyramid, even though a large cemetery with the tombs of members of the ruling family was established around it. The German-American physicist Kurt Mendelssohn was inspired by a visit to Meidum and a view of the peculiar configuration of the ruins of the pyramid to formulate an interesting theory. According to Mendelssohn a catastrophe must have occurred during the final stage of building. In the construction of the external casing, in other words during the conversion of the step pyramid into a true pyramid, erroneous calculations and faulty binding of the limestone blocks caused what is known as a “flowing effect” and the ultimate collapse of the pyramid’s external casing. Although this theory sounds quite seductive, archaeologists have now rejected it and shown that the pyramid at Meidum, like many others, was gradually destroyed by people quarrying it for stone over centuries.

Unfinished white-limestone statue of Djoser in the sed festival courtyard. The festival was celebrated after thirty years of a king’s accession to the throne and was supposed to renew his power. Step Pyramid complex Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

Cemetery at Meidum (photo: Milan Zemina).

Lake and pyramids (Sneferu’s Red and Amenemhet III’s) at Dahshur viewed from the southeast (photo: Milan Zemina).

The Red Pyramid, Dahshur (photo: Milan Zemina).

The reasons that led Sneferu to abandon the pyramid, together with the residence and the town in its neighborhood, have not yet been explained. He chose a new site for pyramid construction approximately 50 kilometers further north and near modern Dahshur. The pyramid that he decided to build in Dahshur was from the very beginning designed as a true pyramid. The chosen angle of inclination of the pyramid walls—60°—proved in the course of construction to be too steep. At the same time, the base on which the pyramid was built was not very stable. The problem was that the foundation was not rock but a compact gravel and sand layer which was unable to bear the pressure of the increasing mass of the pyramid. The walls of the rooms in the heart of the pyramid began to crack. For this reason it was decided to reduce the angle of inclination in the upper part of the pyramid and so considerably lessen the pressure on the inner chambers. As a result of this experimentation and improvisation the pyramid is today called the Bent or sometimes the Rhomboidal or Two-Slope Pyramid. It is unique among pyramids not only for its shape but also for its two entrances, from the north and the west, and the very unusual layout of its inner rooms.

North–south and east–west section of the Bent Pyramid (by A. Fakhry).

It was undoubtedly as a result of the complications during the construction of the Bent Pyramid and in view of the impaired stability of its inner chambers that work was started, a little further way away, on building another pyramid for Sneferu with a relatively small angle of inclination for the outer wall. This is today named the Red Pyramid after the color of the stone from which it was built. It was in this pyramid that Sneferu was probably buried. In the environs of both of the Dahshur pyramids a new cemetery was established containing the tombs of other members of the royal family and high state officials.

The Bent Pyramid. Dahshur (photo: Milan Zemina).

It seems incredible that Sneferu had yet another pyramid built, although this was much smaller than the preceding ones. It stands in Seila, perhaps ten kilometers west of the Meidum pyramid, on a small hill overlooking the depression of the Fayyum Oasis. This pyramid had no inner or underground chambers and was not planned as a tomb but probably simply as a symbol of royal power. The total volume of masonry for all of Sneferu’s pyramids amounts to approximately 3.6 million cubic meters, a building record which none of the Egyptian pharaohs were ever to overtake. The technical, organizational, and administrative significance of this figure can be fully grasped only when we remember that in Sneferu’s time the whole of Egypt from the Mediterranean Sea to the first Nile cataract at Aswan had no more that one to one and a half million inhabitants.

View of the pyramids at Giza from the southeast (photo: Milan Zemina).

Whether because Dahshur was no longer a suitable place to build further great pyramids or because the local limestone quarries did not meet requirements, or for other reasons, Sneferu’s son Khufu (Gr. Cheops) decided to found a new cemetery at Giza, perhaps 30 kilometers north from Dahshur. The site selected consisted of a rocky area of the easternmost promontory of the Libyan Desert above the Nile Valley just where it begins to spread out into the broad delta. Khufu’s pyramid measured about 230.4 meters along each side of its square base. With a wall gradient of 51°50′35″ it reached a height of 146.50 meters. It is the largest of the Egyptian pyramids and is justly called the Great Pyramid and one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Its unique system of internal chambers, especially the so-called Great Gallery and King’s Chamber is, from the point of view of construction one of the most ingenious ever created in Ancient Egypt. In volume the Great Pyramid is approximately 2.5 million cubic meters. Until recently it was believed that it was built with limestone quarried from the rocky massif near the site. The latest geophysical researches—carried out by French scientists—have shown, however, that the core of the Great Pyramid probably consists of solid stonemasonry combined with a system of chambers constructed from stone blocks and filled with sand and rubble. This method was not only very economical and time-saving but also helped to increase the stability of the Great Pyramid during the earthquakes which occasionally occur in Egypt. A number of other buildings were components of Khufu’s tomb and together with the pyramid made up an integrated whole: the valley temple (recently discovered by the Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass but not yet fully investigated), the causeway, the mortuary temple at the eastern foot of the pyramid (today almost nothing remains of this except remnants of paving), the small cult pyramid, five pits for the symbolic burial of boats (one of the two boats which were preserved was raised in 1954) and the three small pyramids of the queens.

Plan of the Giza necropolis (by G.A. Reisner).

North–south section of the Great Pyramid.

Irrigation canal near Giza (photo: Milan Zemina).

This page clockwise: The rock-cut tomb of Kakherptah on the eastern edge of the Hast Cemetery. Fifth Dynasty, Giza (photo: Milan Zemina).

The pillared hall of Chephren’s valley temple, Giza (photo: Milan Zemina).

The ruins of Djedefre’s pyramid (prior to the Swiss-French excavation), Abu Rawash (photo: Milan Zemina).

Khufu’s son and heir Djedefre abandoned the cemetery established by his father and started to build his pyramid complex approximately seven kilometers further north, by modern Abu Rawash. Archaeological finds of numerous fragments of statues of Djedefre, heaped in the pit for the funerary boat, supported the idea that the tomb had been deliberately destroyed as an expression of religio-politically motivated conflict within the ruling house. This theory has, however, been rejected in recent times.

Detail of a statue of the pharaoh Khafre, his head shielded from behind by the outstretched wings of the falcon god Horus. Diorite, 168 centimeters in height. Found in 1860 in the pharaoh’s valley temple at Giza by the French archaeologist Auguste Mariette. The statue is now one of the most famous exhibits of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (no. CG 14) (photo: Milan Zemina).

Another of Khufu’s sons, Khafre (Gr. Chephren), who ascended the throne after Radjedef, returned to Giza. His tomb almost achieved the heights of his father’s pyramid. The complex of buildings belonging to it likewise recalled his father’s monument in its basic characteristics. In Khafre’s pyramid complex the valley temple remains in very good condition, relative to other structures of the same age, and today it is considered another of the supreme works of ancient Egyptian architecture. In this temple, built out of enormous blocks of limestone and red granite, discoveries have included a seated diorite statue of Khafre with the falcon god, Horus, shielding his head from behind with outspread wings. Today, this statue is one of the most famous exhibits in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The Great Sphinx, the lion deity with the human head symbolically guarding not only the ruler’s pyramid complex but the whole Giza cemetery, is also part of the Khafre complex.

The third and smallest pyramid was built in Giza by Khafre’s son Menkaure (Gr. Mykerinos). Despite the much smaller dimensions of his pyramid, Menkaure failed to complete the whole complex of buildings making up the tomb, and including the three small pyramids for the queens, during his own lifetime. This was accomplished by his successor Shepseskaf. Nevertheless, during excavations at the Menkaure pyramid complex an American archaeological expedition, led by George Andrew Reisner, managed to find what is so far the largest group of Old Kingdom royal statues yet recovered. These masterpieces of ancient Egyptian sculpture are today on permanent exhibition in museums in Cairo and Boston.

Just as the members of the ruler’s family and the highest state officials lived their lives in the proximity of their lord and god, so they wished to rest in the shadow of his pyramid and to enjoy his favor and protection even after death. Similarly the Pharaoh himself wished to be forever surrounded by his court, his relatives, and his officials. Thus around the pyramids at Giza—as before in Saqqara, Meidum, and Dahshur—large cemeteries of private tombs grew up. Many of these tombs, and especially those in the vicinity of the pyramid of Cheops, have been excavated by the Reisner expedition, an Austrian expedition led by Hermann Junker, an Egyptian expedition led by Selim Hassan, and others. In the so-called Western Field to the west of the pyramid of Khufu lie the tombs of the ruler’s courtiers, among them the biggest of the Giza mastabas, G2000, unfortunately anonymous and only identified by a number on the archaeological plan of the cemetery. Later tombs are also located here; for example that of the famous Senedjemib Inty, vizier and royal builder from the reign of Djedkare. In the Eastern Field, again in rows, are the equally large mastabas of the highest-ranking members of the royal family; for example prince Ankhhaf, vizier in the reign of Khafre, whose celebrated and splendid bust is today exhibited in the museum in Boston. Also to be found in a dominant position here is the mastaba of Khufukhaf, which perhaps belonged to none other than the future pharaoh Khafre before he became king and changed the element “Khufu” (his father’s name) in his own name to Re, the name of the sun god. Members of the royal family, courtiers, and officials from the reign of Khafre were buried in the Central Field, in the central part of the Giza cemetery south of the causeway leading from the valley to the pharaoh’s pyramid. A rather small cemetery, established in the reign of Menkaure, consists of mastabas and rock-cut tombs lying in an area of former quarries southeast of the pharaoh’s pyramid.

The Great Sphinx with Khafre’s pyramid in the background, Giza (photo: Milan Zemina).

Despite long years of intensive archaeological researches and excavations, however, the royal pyramid cemetery in Giza is still far from fully explored, a fact amply borne out by the surprising discoveries in the area south of the Menkaure valley temple. Here, on the hillside and at the foot of the escarpment, the Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass found a cemetery with the tombs of artisans who had built the royal pyramids. Not far from here, the American archaeologist Mark Lehner discovered extensive mud brick structures of an economic character—the “provisioning section” of the builders of the Giza pyramids including great storehouses for grain and drink, bakeries, and so on. Another important discovery was made by Zahi Hawass in front of Khafre’s valley temple where the remnants of foundation of structures, including two “tunnels” dug through the bedrock, were revealed. The structures, built originally of lightweight plant materials and mudbrick, appear to have been the remnants of a large harbor and buildings occasionally used for Khafre’s burial ceremonies.

The Mastabat Fara’un, smith Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

After the death of Menkaure, there were complications in the country’s internal political situation. The building of gigantic pyramids had drained off major material resources and the mortuary cults had tied up much of the labor force and finances; it was a situation that could not but have a negative effect on economic conditions in the country. The situation was probably further complicated by succession disputes within the royal family and by the growing importance of the solar cult. This is the historical background against which we must interpret the decision of the last Fourth Dynasty ruler, Shepseskaf, to build himself a tomb several kilometers to the south of Giza, in South Saqqara. He did not build it in the form of a pyramid, as was usual for pharaohs at the time, but as a mastaba and, what is more, a mastaba resembling a large sarcophagus. The natives call it Mastabat Fara’un, the “Pharaoh’s bench.” In comparison with the pyramids of Shepseskaf’s predecessors, it was a very small and relatively modest tomb. Its unusual design has led Egyptologists to speculate whether it did not represent Shepseskaf’s deliberate religiously-motivated renunciation of the pyramid shape, so intimately linked with the solar cult (which was ultimately to prevail with the accession of the Fifth Dynasty), and thus a protest against the growing power of the priests of the sun god Re.

Reconstruction of the original appearance of Shepseskaf’s tomb complex (by H. Ricke).

Userkaf, Shepseskaf’s successor and the first Fifth Dynasty ruler, did not abandon Saqqara; nevertheless he had his tomb, again in pyramid form, built within the area of the Step Pyramid, near the northeast corner of its enclosure wall. Userkaf’s small pyramid complex—its valley temple and causeway still as yet unexcavated—attracts attention not only by its eloquent siting near Djoser’s pyramid but by reason of two particular features. First, the mortuary temple was not built at the eastern foot of the pyramid, as one would expect from the standard, religiously-motivated east-west orientation of the whole complex, but at its southern foot. The unusual siting of the temple was almost certainly influenced by the existence of a broad and deep ditch, called the Great Moat, enclosing the precincts of Djoser’s pyramid complex. The ditch ran precisely across the area where, under normal circumstances, the mortuary temple should have been sited. In order to be buried close to Djoser’s pyramid, Userkaf was prepared to change the standard plan for his tomb. The second notable feature is Userkaf’s wife’s independent pyramid complex built to the south of the ruler’s mortuary temple. The queen’s mortuary temple was the largest of its kind to have been constructed up to that period.

Reconstruction of Userkaf’s pyramid complex without causeway and valley temple (by H. Ricke).

The pyramids of Abusir (photo: Milan Zemina).

The majority of the Fifth Dynasty rulers had themselves buried in the cemetery at Abusir, established as an indirect result of Userkaf’s construction of his sun temple here. Pyramid complexes were built at Abusir by the rulers Sahure, Neferirkare, Neferefre, and Niuserre (for further details see Chapter II). In the vicinity of their pyramids, several smaller cemeteries grew up for members of the royal families, courtiers and high state officials. It is noteworthy, however, that many of the leading dignitaries of the Fifth Dynasty did not have their tombs built at Abusir, near their kings, but at Giza or Saqqara. One example is the magnate Ti, who occupied high offices during the reigns of Neferirkare, Neferefre, and Niuserre and was even administrator of these pharaohs’ pyramids and sun temples, but who built himself a tomb in North Saqqara. Ti’s mastaba is considered the most beautiful of the tombs of the Old Kingdom yet discovered. This is because of the well-preserved state of its relief decorations, the artistry of their conception, the diversity of the subjects depicted from everyday life and from the mortuary cult and, last but not least, the quality of the workmanship.

Fragments of a red granite palm column in Djedkare’s pyramid temple, south Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

The tomb of Niuserre’s successor Menkauhor has so far not been discovered. Some archaeologists are searching for it in North Saqqara, others in Dahshur. Menkauhor was not, however, buried at Abusir, and neither were the last two Fifth Dynasty rulers, Djedkare and Unas. Djedkare’s pyramid complex, and a neighboring and comparatively large pyramid complex of the pharaoh’s wife, were built at Saqqara, roughly half way between Djoser’s pyramid and the Mastabat Fara’un. The complex, already severely damaged in preceding centuries, met with misfortune of a peculiar kind in the modern period. At the end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s two archaeological expeditions carried out excavations there. The results of the work were not, however, made public and a part of the documentation was lost, so this complex remains one of the least-understood of all royal funerary monuments of the Old Kingdom.

The ruins of Unas’s valley temple at Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

Low relief with polychrome of Ptahhotep sniffing a vessel of perfumed ointment Mastaba of Ptahhotep. Fifth Dynasty. Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

Scene depicting a range of funerary offerings with boats and unfinished statues of the tomb’s owner. Tomb of Irukaptah, Saqqara. Fifth Dynasty. Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

The last Fifth Dynasty ruler Unas, like Userkaf, found a place for his tomb near Djoser’s pyramid, but at its opposite end. Although Unas’s pyramid is one of the smallest monuments of its type from the Old Kingdom, it represents a turning-point in Egyptian history. This is because on the walls of the pyramid’s underground chambers are the first recorded religious inscriptions which Egyptologists call the Pyramid Texts. These are groups of poems, litanies, hymns, and other writings, apparently dating from various periods, but linked into a single whole, and first transcribed in the pyramid of Unas. Their purpose was to ensure the ruler a path to eternity and life among the gods in the other world. In the vicinity of Unas’s mortuary temple and causeway lies a cemetery containing mastabas and rock-cut tombs, many of which belong to members of Unas’s family, courtiers, high state officials, and the priests who maintained the ruler’s mortuary cult. In this cemetery lies the rock-cut tomb of Nefer, with the best-preserved mummified body from the Old Kingdom, and also, among many others, what is known as the Tomb of the Two Brothers, Nyankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, a tomb which is outstandingly well-preserved and original in its relief decoration.

Burial chamber and sarcophagus of Unas. On the side walls of the chamber are Pyramid Texts and the ceiling is decorated to resemble a starry sky (photo: Milan Zemina).

The pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty built their tombs exclusively in Saqqara. The first of these, Teti, had his tomb constructed in the northern part of Saqqara near the Early Dynastic royal necropolis. His pyramid complex closely resembles that of Unas, and includes the Pyramid Texts. These texts are, in fact, to be found in all the later pyramids of the kings and even in some of the pyramids of the queens right up to the Eighth Dynasty. Around Teti’s pyramid and especially north of the monument a large cemetery was established for magnates and officials, and this contains the famous tombs of the Vizier Mereruka, the vizier Kagemni, the physician Ankhmahor, and many others. The relief decorations preserved in these tombs are astonishing for the variety of the subjects depicted, although the quality of execution often does not reach the level of the masterpieces of the Fifth Dynasty, such as those in the tomb of Ti in North Saqqara or in that of Ptahshepses at Abusir.

The portrait of Ankhmahor in sunk relief. Ankhmahor’s tomb. Sixth Dynasty. Saqqara (photo: Milan Zemina).

The pyramid complex of Pepi I is located in South Saqqara, not far from that of Djedkare. Research there, carried out by a French archaeological expedition directed by Jean Leclant and Audran Labrousse, has recently made the surprising discovery in the area around the king’s pyramid of six small pyramid complexes of the wives of Pepi I. The possibility that still more remain to be discovered is not to be ruled out.

Plan of the pyramid complex of Pepi II (by G. Jéquiér).

The last great pyramid complex of the Old Kingdom was built at the end of the Sixth Dynasty by Pepi II. The complex, already excavated before the Second World War by a French expedition this time led by Gustav Jéquier, lies at the southernmost edge of Saqqara, close by the Mastabat Fara’un. In layout it resembles the tombs of Pepi II’s predecessors of the Sixth Dynasty. Its components also include three small pyramids and the mortuary temples of the queens Neith, Iput, and Udjebten. There is even a small cult pyramid sited near the southeastern corner of the pharaoh’s pyramid. During investigation of what were hardly the most numerous remains of relief decoration in the mortuary temple it was demonstrated, surprisingly, that its creator had been inspired by the reliefs from Sahure’s mortuary temple at Abusir. This is indirect proof not only of the standardization within the decoration of the royal pyramid complexes but, at the same time, also of the high artistic level of the decoration of Sahure’s complex, an achievement which became the model for subsequent generations of artists and craftsmen. The same is true, in another form and at another time, of the monument of Pepi II in South Saqqara. This too later became a source of inspiration for the builders of the pyramids of the Middle Kingdom pharaohs. These, however, were for the most part not sited in the Memphite necropolis and, by the time they were built, Memphis had ceased to be the capital city of Egypt.

View of Sahure’s pyramid from the southern portico of the pyramid temple (photo: Kamil Voděra).