16

COMMANDER TO THE CORPS

The opportunity for Monash to do whatever he wished in the region came sooner than anticipated. On 12 May, Birdwood recommended him to the Australian Government for the corps command. Birdwood himself was on his way to run the Fifth Army. He had wanted to stay and had dreams of controlling a huge Dominion army of Australian, Canadian and New Zealand divisions. But it wasn’t to be. Yet he hung on to a quasi-management of the Australians by retaining administrative command of the corps.

Birdwood felt there were only two real candidates for Corps Commander: his own deputy White and Monash. He adored White, who was the administrative brain behind him. But Monash was his senior. He had commanded in battle. White had not.

‘Monash has commanded first a brigade then a division in this force without a day’s intermission since our training days in Egypt in Jan. 1915 to the present time,’ Birdwood wrote, putting his case to Hughes and Pearce much more firmly than he did when recommending Monash for a division command a year earlier.

‘Of his ability, there can be no possible doubt, nor of his keenness and knowledge,’ Birdwood continued. ‘Also, he has had almost unvarying success in all the operations undertaken by his division, which has I know the greatest confidence in him.’ Birdwood was mindful of the hysteria in some circles in Australia about Monash’s German background, which had made Hughes nervous. ‘This has, I think,’ Birdwood added, ‘been entirely lived down, as far as the AIF is concerned, by his good work.’ The good work was killing Germans. Gone were the feeble fears that Monash might baulk at fighting them.

Birdwood concluded, in a firm manner for him, with: ‘I do not think we can in justice overlook in any way his undoubted claims and equally undoubted ability to fill the appointment.’1

Not even Monash’s reluctance to ride around on a horse to cheer up the troops was now held against him.

To be fair to Birdwood, he had to couch his recommendation in double negatives and caution. In theory, the Australian Prime Minister had more power than he concerning Australian troops. If any British war leader tried to be dictatorial it would not be diplomatic and could lead to a backlash. In reality, Hughes and every politician knew that the judgement on the best man to run the corps had to come from superiors inside the British High Command.

Hughes had reservations about Monash. The most influential voice in his ear, that of Keith Murdoch, was set against Monash. Hughes had happily inherited Murdoch from former Prime Minister Andrew Fisher after his commission of the journalist to assess Gallipoli. Murdoch had been Hughes’ agent in pushing hard in England’s power circles for the formation of the Australian Corps. Since this had succeeded too, Murdoch was now a strong, precocious political player in his own right. He had first been alerted back in March 1918 when chatting with Haig that Monash was favoured for the top spot. This annoyed Murdoch and upset Bean. The latter, it seemed, had never recovered from the ticking off he had received from Monash on Gallipoli over the journalist’s lack of reporting of the gutsy efforts of his 4th Brigade. This, plus Bean’s affection and enormous respect for White, caused him to oppose Monash. A third factor was Bean’s anti-Semitism. Monash could have his Jewish background as long as he didn’t have too much influence. But Bean would not have someone he described as a ‘pushy Jew’ running the most important position in the AIF.

On this one major issue in his distinguished career, Bean stepped out of his role of recording military history and decided to create it himself. His intrigues with Murdoch for the not-so-merry months of May and June 1918 were never recorded in their writing for public consumption. But for a short period they jostled centre stage with key politicians and military men in attempt to get their way.

They saw any appointment by the British High Command as the wrong one. They suspected that the choice would have to be under its thumb and therefore someone who would not look after Australian interests. They felt compelled to support the most appropriate Australian, who had not been selected by the British. It was loose logic, and it underestimated the chance of any Australian chosen (in this case Monash, who could not have been more pro-Australian) to be in a position to look after his country’s interests, if he were strong enough.

Both men ditched honesty and integrity in a near-hysterical drive to block Monash and have White take command of the AIF. Bean first heard the news from Birdwood on 16 May. Monash would be commander; White would go as chief of staff with Birdwood, who would be the British Fifth Army Commander and head of AIF administration.

Bean was stunned. At this time, he spoke about Monash to Birdwood’s deputy adjutant general, Colonel Dodds. Bean’s imagination and hyper-bole were running wild. Monash, he said, had worked for corps commandership ‘by all sorts of clever well hidden subterranean channels’.2 Dodds was not happy with the accusation. He guarded all the plotting channels that led to his boss’s desk. Monash had never appeared in any of them. He – and White for that matter – were not schemers, except against the Germans.

‘You are an irresponsible pressman,’ an angry Dodds told Bean.

But Bean, the correspondent-as-commander-maker, was hell-bent on making his case. In pushing aside Dodd’s rebuke, he first had to convince himself by preaching to the converted – himself – in his diary. He recorded that he ‘blurted out’ to Will Dyson, an official war artist, and Hubert Wilkins, a photographer, the news about Monash and found there was ‘immediate consternation’. This reaction was understandable from two men employed by White and attached to AIF HQ. Despite the fact that they were unqualified to judge the merits of the candidates on any level, their views formed the basis for extrapolation of the two conspirators’ argument that there was strong opposition to Monash’s appointment.

Bean set the agenda of the discussion with Dyson and Wilkins. ‘We had been talking of the relative merits of White who does not advertise and Monash who does,’ Bean informed his diary on 17 May, exposing his position. Dyson, who as a military expert made an excellent sketcher, became the lynchpin of Bean’s argument. ‘Dyson’s tendencies are all towards White’s attitude,’ Bean wrote and then quoted Dyson’s rendition of this: ‘“Do your work well – if the world wants you it will see that it has you.”’

Bean then seemed to have Dyson arguing against his case. ‘Dyson thinks it (White’s if the world wants you attitude) a weakness. But he [Dyson] takes it better than the advertising strength which insists on thinking or insinuating into the front rank.’ This brought Bean full circle to his racist bias, which was his root objection to Monash. Here he quoted another’s similar prejudice: ‘Dyson says – “Yes, Monash will get there. He must get there all the time on account of the qualities of his race; the Jew will always get there.”’

Bean then finished this diary entry, allegedly quoting his mouthpiece again, and reduced his own argument to absurdity: ‘I’m not sure that because of that very quality Monash is not more likely to help win the war than White. But the manner of winning it makes the victory in the long run scarcely worth the winning.’3

The correspondent’s intellectual hand-wringing (which Bean forty years later recanted by admitting that Monash had not pushed for the commandership) was not as threatening to Monash as Murdoch’s manipulation. He knew more about clever, well-hidden subterranean channels than any political troglodyte. His successes behind the scenes fuelled him for more attempts to have influence over events. Dictating the choice for the first ever Australian AIF commander was as big an issue as he was likely to ever see. Whereas Bean was playing an uneasy, unusual role for him, Murdoch was right in his element, and without his co-conspirator’s fever about Monash’s background. Murdoch didn’t care if he were a Jew or Gypsy. He had to go. White should be in the top saddle. He was thought to be a far easier character to manipulate than Monash, whose cerebral capability made him less malleable for Murdoch’s purposes.

Murdoch met with Bean and Dyson in London on 18 May. Dyson was asked by Bean to repeat what he said about White and Monash. Murdoch scribbled notes, which encouraged Dyson, whose creativity had until now been restricted to art, to be bold. The AIF wanted White, not Monash. Everyone he met or painted was saying it. The would-be kingmakers were in quick accord. Monash should be offered a big desk job in London – as administrative head of the AIF. White should be commander. And Birdwood, who now was running the admin AIF job and the Fifth Army? Well, Birdie could run the Fifth Army if he wished, but he would have to give up his admin desk at AIF London.

The two plotters went into action. Bean sent a telegram to Pearce advising him not to allow White to be lost to the Australian Corps. He was ‘universally considered greatest Australian soldier’. Murdoch cabled Hughes in the USA making the demands and citing his deep research, which, in actuality, was the discussion with Will Dyson the day before. The artist morphed into ‘some officers’. They claimed ‘that in operations strategy and understanding of Australians [White] is much superior to Monash whose genius is for organisation and administration and not akin to the true AIF genius of front line daring and dash’.4

The fact that White had never commanded under battle conditions and that front line derring-do was not relevant to the position, whether Monash or White had that or not, was not mentioned. To say that Monash had less comprehension of his fellow countrymen was specious and unprovable. And they were both exceptional administrators in their own way.

Hughes, who until now had enormous faith in Murdoch and his judgements, went into a flap. He was in Washington, a long way from home, and disgruntled. He cabled Pearce, whose cable machine was now jammed with demands and counter-demands. But the distance from Melbourne was proving tyrannical. Pearce had approved Birdwood’s recommendation of Monash five days ago. Hughes let Murdoch know.

The journalist had plenty of subterranean avenues of attack left. The political path was blocked, so he went the press route by cabling the Sydney Sun. The crisp message, claiming there was a ‘strong unanimous view’ (those of the artist, the historian, himself and perhaps the cook who came to dinner) and then cited the demands. Murdoch’s language was cute. He now referred to Monash as the ‘supreme administrator’, perhaps thinking that he might be flattered into taking up the position if such a title were aired in the press. But there were now more blockers than in a blood pressure pill. This time the Australian Chief Censor rejected Murdoch’s cable. But the censor had a two-way bet by deciding not to announce Monash’s appointment either. He would hold it back for a month to see whether it stuck.5

Murdoch was as resourceful as he was politically expedient. He now turned Federal Government lobbyist and persuaded businessmen and a union boss to get their mates in high places to make representations to Hughes and Pearce.

His fourth line of attack was his first real foray into the military ranks. He attempted to persuade Birdwood to give up his London AIF administrative job. His argument that Birdwood should not prevent an Australian from having the position didn’t wash. Birdie was shrewder than his demeanour advertised. He didn’t bother with shorthand, cryptic, overly dramatised cables. Instead he put his thoughts on paper by writing to Pearce (copying Hughes) and the Governor-General, Munro Ferguson, who hated to miss anything.6 He summed up Murdoch as an ‘Australian Northcliffe’. This reference to the just-gonged Viscount Northcliffe, who at sixty-three had developed megalomaniac tendencies recently, was pointed and perspicacious. Northcliffe owned the London Evening News, the Daily Mail and The Times, which gave him enormous clout in the years before television and radio. He used his papers ruthlessly to get what he thought was right for the empire without regard to fair reporting.7

Murdoch, at thirty-two, would have loved the comparison but not the inference. Birdwood claimed that Murdoch’s efforts had stirred up anger and resentment at AIF HQ. Dodds, still simmering from Bean’s accusations about Monash, also wrote to Pearce. Seeing through the plot by the artist, the correspondent and the mini-Northcliffe, Dodds told the defence minister that Murdoch was misrepresenting AIF opinion.8

But Murdoch kept on. He showed he had learned much by being around politicians by his fifth tactic of setting up Monash for an attempted bribe. First Murdoch wrote the softening-up letter to him offering warm congratulations. Monash replied politely, as he would have done to anyone. A day later Murdoch responded more expansively without giving anything away. Monash’s instincts were alerted. He knew there was a push by Murdoch, Bean and Hughes to replace him with White, and he saw Murdoch as a danger and ‘profoundly distrusted’ him. Any overture from him, which would have Hughes’ backing, should be received with caution.9

Monash consulted Birdwood, who suggested he write to Hughes urging him not to change the new set-up at least until after he had visited him (Monash) and his troops.

Then came the bribe. Murdoch, writing with his address as ‘The Times office’ began with what Monash regarded as red lights flashing: ‘… men … have in some insidious way tried to lead you to regard me with suspicion and even with hostility, just as on occasions some have whispered and lied to me about you.’ Next, the flattery: ‘I do want to say earnestly that I value your extraordinary ability very highly as an Australian, and I have always admired your work as a soldier. It takes two to make a friendship, of course, but please let me assure you that you have my personal esteem as one young Australian towards a much abler and wiser compatriot.’

Then Murdoch tried apparent candour by telling Monash what he already knew. Murdoch had recommended White as Commander of the Australian Corps. ‘I honestly thought your genius would lie in the somewhat higher sphere of administration and general policy.’ He again referred to Monash’s ‘genius’ and how he had been telling ‘high authority’ in London about it.

Then Murdoch painted a black picture of the eventual alternative to him. An Australian cabinet minister might have to be placed in London with a military staff. This was an attempt by Murdoch to appeal to the army’s aversion to political interference. He puffed up the London desk job as much as he could, adding that Birdwood was English. How could he possibly handle political issues on Australia’s behalf? It was a worthy point, but not the main argument. Two big inducements were put to Monash, now a lieutenant general. The first was that he would be made a full general if he took the position. This would have been very fast tracking for any army. The second was meant to appeal to Monash’s ego and vanity. Murdoch’s articles were cabled to 250 newspapers worldwide. Murdoch offered to be the conduit for Monash’s views on a grand scale.

Murdoch’s case would have made Machiavelli proud. It was cunningly crafted by a young master political strategist. But there was one problem. Murdoch underestimated and misread his man.10 Murdoch would have known about Monash’s concerns for recognition, both awards and publicity, but misunderstood the motives, especially where his brigade, division and now corps were concerned. Monash had long seen publicity as a device for gaining a stronger voice and therefore position for himself and the men under him. Awards (VCs, mentions in despatches and so on) were recognition for deeds done and useful prestige. Gongs were nice for one’s image. But above these accolades, for an outsider who thrived on them, Monash was driven by the need for him and his troops to have an independent powerful voice and control over their own destiny.

He was the first Australian in a position to have a real say in how the AIF conducted itself in war. It was now being manoeuvred into a critical position of impact, where it and the Canadians could be the most powerful force on the Allied side in the conflict. Monash had spent a lifetime in the militia and three years in the thick of the most important war in history. This was his time, and he knew it. There was no way he would pass up the chance to run what was to him a mighty fighting force that would – he was convinced, if properly managed and directed – play a major part in defeating the German Army.

Monash’s deep sense of history also wouldn’t allow him to back out. He had studied all the major wars of the last 150 years and was conscious of the current conflict’s place in history and of the power of the force now in his hands. The AIF was by far the biggest corps of either side.

‘My command is more than two and a half times the size of the British Army under the Duke of Wellington, or of the French Army under Napoleon Bonaparte, at the battle of Waterloo,’ Monash wrote home in the middle of the Murdoch–Bean–Hughes intrigue. ‘Moreover I have in the Army Corps an artillery which is more than six times as numerous and more than one hundred times more powerful as that commanded by the Duke of Wellington.’11

Size mattered to Monash. He salivated at the flexibility it presented him in the ability to conduct battles. For many commanders, this sort of elevation was dizzying or intimidating. But not for him. He couldn’t wait to get his engineer’s brain on bigger maps, resources, ideas and opportunities to win. Perhaps above all else, Monash was quietly but mightily proud that he, the outsider, had risen to be Australia’s first native-born commander-in-chief. He was insulted by Murdoch’s try at suborning him.

‘It is a poor compliment,’ Monash wrote in his diary, ‘both for him to imagine that to dangle before me a prospect of promotion would induce me to change my declared views, and for him to disclose that he thinks I would be a suitable appointee to serve his ulterior ends.’

It took all his considerable diplomacy to restrain himself from telling Murdoch and Bean what he thought of their caballing, especially at this critical time in the war. At first, he wrote a neutral, friendly response to Murdoch avoiding comment on the bribes. Its passivity concerned him. He drafted the start of another response, explaining his desire to prove himself as a corps commander.

‘You and your friends believe my abilities are mainly administrative,’ Monash began. ‘You probably think that a non-professional soldier is unlikely to be a good commander; that in the past I have been a figurehead controlled by professional soldiers …’12

But he put his pen down. He couldn’t go on. It was too much from the heart; too revealing. Monash was beginning to understand his two adversaries. He was aware of Bean’s unqualified admiration for White. Hero worship was something he could overcome, by his success on the battle-field. Racism, which Monash sensed from Bean, was something he had lived with and which he accepted from people who didn’t know or understand him as a human being. Although Bean’s judgements were distorted by this blind spot, he seemed by nature to be trustworthy and not dishonest.

But Murdoch was a far bigger problem. Whereas Bean genuflected to his ideal man, Murdoch’s ego wouldn’t allow him to bend the knee to anyone. Murdoch behaved as if he was on a par with Prime Ministers, heading to some place with an even greater power base. He appeared to believe that everyone had a price and could be bought in pursuit of his (Murdoch’s) aims and position of ultimate potency.

Better, Monash thought, not to give the plotters anything to work on or with. The second letter was never completed or sent.

It might have been the correct move in his fight for self-preservation. The two-man undermining team kept their campaign running. They bailed up AIF officers and politicians anywhere they could find them and tried to make their case against Monash and for White. But there were none with influence among them who would put his name to their cause.

The issue reached a head in mid-June 1918, when Hughes arrived in London. Every key officer in the AIF, including Birdwood, rushed to greet him, except the new chief, Monash, who stayed at Bertangles, pointedly working on a new battle plan. The political wrangling began. Birdwood proved loyal to Monash. Where Birdwood had often been cautious in war in speaking his mind to Haig, he felt freer in front of the blunt-talking Australian politicians and conniving journalists to say what he believed.

At an official reception for Hughes, Andrew Fisher, who had been High Commissioner since 1916, was contemptuous of Monash. Birdwood told him to his face that he didn’t know what he was talking about, which was accurate. Murdoch was there. ‘Do you really think Monash is fit to command the corps?’ he asked, which was not a thoughtful probe, given that Birdwood had made the appointment.

‘Of course,’ Birdwood replied. ‘He can do it better than I.’

The Fifth Army Commander was working the room on Monash’s behalf, or was it working him?

Hughes chatted to him about Monash, and Birdwood expressed his confidence in him. He dropped the names of two officers whom Hughes knew were heavyweights in the British Army – Generals Plumer and Rawlinson – who also supported Monash and had great faith in him.

A key player who had kept in the background and not been consulted in the Murdoch–Bean schemes was White himself. He had not wanted to contradict his boss, Birdwood. Now with Murdoch openly attempting to lobby for him, White was embarrassed. He wished to distance himself. He told Birdwood he would not accept commandership of the corps if it were offered. It would suggest, he said, ‘that I’ve been intriguing with Murdoch’.

Maybe. But it didn’t stop Murdoch and Bean. They saw these functions in the summer of 1918 as the chance to secure what they had so feverishly pursued now for months.

The movable feast of political gyrations spun on to the Ritz Hotel for another reception for Hughes by the British Government and War Council. The two journalists networked the ballroom. Murdoch kept checking who was there. If they were important enough he was in their ears. Lord Milner, Secretary of State for War, was not impressed. Rawlinson listened but didn’t like what he heard. Later, he referred to Murdoch as ‘a mischievous and persistent villain’.13

Bean, less proficient in the Byzantine ways of political lobbying, reverted to his real forte: writing. He sent Hughes a memo setting out, point by point, the case for White and against Monash (and Birdwood, who would lose his AIF position if their coup was successful). He also wrote to White. His letter was too emotional and too much like hero-worship for the recipient’s liking. White dismissed the appeal to second him.

This proved a problem for the two kingmakers. Their potential king would rather remain a prince. At heart he didn’t really want the job desperately enough. Certainly not as much as his wily supporters would have wished. But Murdoch and Bean knifed on, convinced of their rightness.

Their messianic approach ignored salient points. One was that Monash’s popularity – from the grass roots up to the top of the AIF and with the British military and beyond – had been growing since the day he had taken charge of creating 4th Brigade in October 1914. His reputation had been established in those forty-four months. A backlash against the plotters was beginning, and Monash had powerful cards to play. Apart from Birdwood, Army Commanders Rawlinson, Plumer and Gough would support him. Then there was the Commander-in-Chief himself. Haig had the AIF commander’s position earmarked for Monash almost as soon as he had taken over the 3rd Division.

Then there was King George, whom Murdoch and Bean could not hope to overcome even if they were aware of any interest he might have had in the matter of the Commander of the Australian Corps. Monash could never appeal to him. Nor could the King step in and support him. But the mere fact that Monash was a King’s favourite son in his army, and that Haig and others were aware of it, weighed in Monash’s favour. Haig, who said Monash could take another army corps command if the Australian cabal managed to dislodge him, had already presented a fallback position.

Yet Monash would wish only to run the AIF.

Monash’s geographic distance from the politicking at the Ritz didn’t stop him defending himself. He took time out to write in his own defence to Pearce, and to listen to Birdwood’s report of what was said at the receptions for Hughes. The reports were unsettling and prompted Monash to see the Bean–Murdoch plot in anti-Jewish terms. He wrote home with more of a dry observation than a feeling of persecution, which he had not expressed before: ‘It is a great nuisance to have to fight a pogrom of this nature in the midst of all one’s anxieties.’14

Through all this, Monash got down to running the four divisions of the AIF at his disposal. 1st Division was still stuck in Flanders at Hazebrouck and Merris doing defensive work for British XV Corps. At first his style was seen to be far different from that of the affable Birdwood, and it caused wonderment among staff and officers. Monash was happy to ride around in the Rolls-Royce that Birdwood had used, except that he put a bigger Australian flag on it. He thought that the HQ atmosphere was too slack. He made all ranks salute, so much so that very soon everyone from the lowliest private up seemed to have an arm tic. Monash didn’t mix like Birdwood, who was popular because he stopped to make small talk and remembered names easily. Monash rode or walked around with a frown, not in anger but deep in thought, and only occasionally worked on his attribute of the common touch. Days after Birdwood and White had left for London to take up their new posts on 31 May, Monash was heard barking at his aides. No one knew that they were his nephews (‘Mo’ and ‘Half a Mo’) and that they adored him anyway. He was also brusque on the phone. If the recipient didn’t get the finely articulated command first time, then it was bad luck. There was less room for niceties and chat about the weather.

Monash was also running the corps with certain ambitions. Whereas Birdwood was not a planner who drew up battle schemes, Monash had the job with two aims in mind: to defeat the German Army and to prove himself a commander. When Birdwood had all the divisions under his control he was content to wait for C-in-C Haig or Fourth Army Commander Rawlinson to direct him, at least for the time being. He was happy to tread water. He knew he was going elsewhere and was in transit. Monash had no intention of going anywhere else. He had arrived at the right destination for him. He would of course accept directions and orders from Rawlinson and Haig, but he would be attempting to set his own agenda, which they would receive from him as battle proposals.

Monash was determined to sharpen the HQ atmosphere. It would be in keeping with his drive and aims. In parallel, he had to settle his command and staff, and this had to be done in collusion with Birdwood and White. His divisional commanders were a priority. Out went Walker (1st Division) and Major General N. M. Smyth (2nd Division), the last of the senior British regulars. Glasgow and Rosenthal replaced them. His old 3rd Division leadership was more problematic. McCay, who had originally bid to take over the AIF, had coveted it, but Birdwood didn’t want him anywhere near the corps. He thought Monash’s long-standing friend was too abrasive for a command in the revised formation. Monash might have agreed, but he had another problem with McCay.

They had been rivals since McCay had beaten him to being dux of Scotch College in 1880. McCay had headed him into the AIF and into running a division. McCay had always been his senior; someone he confided in and complained to about his apparent perpetual outsider status. But in the past year their roles had reversed. Vic had danced a little jig of victory when Monash received a higher-ranked knighthood at the beginning of the year. Monash himself did not. He had not rejoiced in the down-grading from divisional commander to depot commander of his once-illustrious rival. McCay had felt the strain of battle command as a man in his early fifties was expected to do in a young man’s game. Now Monash was embarrassed at the thought of being his boss. It just wouldn’t work.

Birdwood offered him McCay for 3rd Division knowing Monash wouldn’t accept him, which allowed Birdwood to slip in White’s choice and friend, Major General Gellibrand, who had displayed heroic leadership, notably at the second battle of Bullecourt. He was often prickly to those above and below him in rank. He also had some prejudices against Monash, which he expressed in Egypt when there were rumoured doubts about Monash’s German allegiances.

Gellibrand proved true to form within days of his appointment, clashing with McNicoll, who regarded his new superior as both bombastic and overbearing. Gellibrand, for his part, thought that McNicoll’s 10th Brigade was slack and undisciplined. McNicoll complained to Monash, saying he wanted either to resign or transfer. Monash attempted to smooth matters. Despite some frustrations over the years, he had a high regard for McNicoll’s combat leadership and courage. He didn’t want to lose him. In the end he had the two men agreeing to disagree in the uneasiest of alliances. Gellibrand remained abrasive, and McNicoll remained unhappy. McNicoll considered Monash a brilliant commander and accepted his toughness and demanding style when combat was on. He knew that Monash had firm control of the levers. He had complete faith in his fast decision-making under pressure. But he worried that Gellibrand, for whom he had no respect, would be a blustering bully in tense moments.

Although Monash was not entirely satisfied with the choices, the new-look AIF leadership was now more or less in Monash’s image: Australian and with a volunteer citizen-soldier flavour. He also had only a partial say in his own staff. He was content with his chief of staff, 33-year-old Brigadier General Blamey, who had a reputation for working and playing hard. He was a former teacher from Wagga Wagga in New South Wales and an army regular since 1906. He also had a good record at Gallipoli. The administrative head was Brigadier General R. A. Carruthers, a close friend of Birdwood. Monash didn’t like his laziness and wanted him replaced by the brilliant soldier and manager, Major General Bruche. But Birdwood, as head of AIF administration, had the power of appointment at least at this early stage, and he won the battle of the friends, despite putting up a weak argument. Bruche had German origins. Birdwood told Monash that he didn’t want that issue being revived. Monash thought about asking Birdwood if he wished to replace the King on the same grounds, but decided to accept the ‘extremely stupid’ ruling.15 Carruthers’ slothful work practices in the office would not impinge on planning or combat operations. Besides, he was charming and amusing. His competent assistant, Lieutenant General G. C. Somerville, made his shortcomings tolerable. The only other senior British officer was the heavy artillery commander, Brigadier General L. D. Fraser. Monash’s long association with artillery made him a critical judge of this position. He thought Fraser was the best available man.

Another capable assistant was the urbane twenty-six-year-old Australian major, R. G. Casey, who was from a new generation and young enough to be Monash’s son. The AIF staff then was a blend of maturity and youth, volunteers, regulars, Australians and a handful of experienced British officers. It was an excellent pool on which the new commander could draw for ideas, inspiration, experience and intelligence.

Monash would need all of them working in harmony to achieve his aims. If Hughes could be kept at bay, Monash would have just three superiors in the British Army he had to sway to have his battle plans implemented. The top two were Rawlinson and Haig. Fifty-four-year-old Rawlinson was a veteran of the 1886–87 Myanmar Expedition, the 1898 Sudan campaign and the Second Boer War of 1899–1902. His Fourth Army chief of staff, Archibald Montgomery (later Montgomery-Massingberd) was the third party he would have to keep on side.

Monash’s focus now would be on understanding them, their motives, fears and aspirations. With the characters, foibles, strengths and weaknesses of those above him clear in his mind, he now set out to impose his will – ‘a moral ascendency’ – over his entire staff. He wanted them to think as one, and he was number one. There was to be a single administrative and tactical policy. Yet the atmosphere at HQ was far less dictatorial than this aim would suggest.

Monash ran the army (which it was becoming in all but name) as if it were a huge engineering operation, or even the way an editor would run a newspaper. Everyone had access to his office, and the atmosphere was less disciplined and more relaxed than anything ever seen in the Australian force or any other British army. Monash refused no one and remembered everything, absorbing opinions and views like a sponge. His objective was to leave nothing to chance. This meant exhausting staff work to cover every contingency, in depth. And like a good newspaper boss, he prepared no editorials or plans without comprehending all concepts put to him. His overarching schemes would embrace what he saw as the best points.

The final act before battle while he was in charge would be the conference, which Birdwood had avoided. Monash used conferences to create a uniform tactical thought and method throughout his command. A conference would see an open and free exchange of ideas that would develop teamwork and efficiency and settle the final battle plans. Then the general would be prepared to move with confidence and allow his natural instinct for offence to run free.

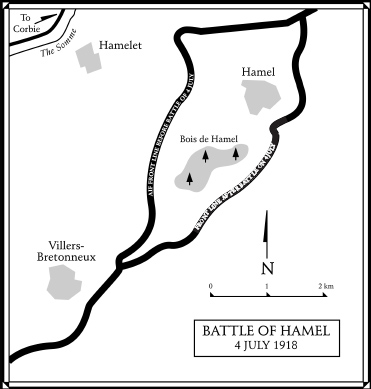

The first plan that Monash was ready to put to his superiors concerned that irritation he wished to remove surgically: Hamel. It sat neatly on the other side of Vaire Wood just two and a half kilometres northwest of Villers-Bretonneux. Since taking command on 31 May, Monash looked over at the area every day. It caused him to frown as if the Germans wandering about in full view of his field glasses were goading him. The Allies had not made one sizeable offensive since Passchendaele seven months ago. Monash believed that the rumours about imminent German offensives, especially from prisoners, were more bluff than reality. He wanted to take the initiative, not with the slaps of raids, nor the knockout right cross of a massive counter-attack, but with a sharp jab that would wind the opposition and lower its morale.

Monash wanted something special to start his campaigns as a corps commander. The use of tanks was very much in his thinking. Early in June he jumped in his Rolls with Blamey and drove thirty kilometres to have a long chat with the commander of the British Tank Corps attached to the Fourth Army, Major General H. J. Elles.

They were shown the latest models: the Mark V and Mark V Star. They looked like their predecessor, the tank that had so let down the Australians at Bullecourt. But there were big differences. The Mark V only needed one pair of hands to drive it instead of four pairs. The special gears, the greater power and ‘the improved balance of its whole design’, Monash the engineer observed, ‘gave it increased mobility, facility in turning and immunity from floundering in ground even of the most broken and uneven character’.16 The more powerful engines rarely broke down. Its reinforced armoured shell could take anything short of a direct hit from a field gun. They were quicker, too, or at least less slow, at five kilometres per hour.

Until now, the tank had been viewed as a defensive weapon, one that formed a mobile shield for infantry. But Monash wanted to know whether they could be used, like his doctrine on machine-guns, as offensive weapons. Elles was adamant that they could. He spoke effusively about tanks leading raids and causing havoc behind enemy lines. A direct artillery hit would be near-impossible if the tank rolled into an enemy camp and smashed up an HQ. That made the vehicle unstoppable. Haig would allow this next year, Elles informed them.

Was it possible now? Monash asked. Yes, was the reply.

Monash and Blamey returned to Bertangles with a daring possibility to consider.

‘I proposed an operation for the recapture of Hamel,’ Monash wrote. It was conditional on the use of tanks, a small increase in his artillery and an addition to the AIF’s ‘air resources’.17

Tanks dominated the first draft plan of attack in Monash’s mind. But he needed to win over the allegiance of his men, who were no lovers of these oversized mechanical killers. They had only bad experiences or heard only bad stories about them. There was another pertinent factor. Tanks would usurp their role in the battle. These men hadn’t come to fight on the Somme as second-stringers to armoured vehicles. Monash arranged for the likely participants to go by bus to Vaux, a village tucked away in a quiet valley northwest of Amiens, where they spent a day with Elles’s corps. The show turned into a party. Groups of soldiers rode around in tanks. Their forward and reverse gear flexibility was demonstrated.

Mock machine-gun nests were constructed. The tanks were rolled and backed over them. The soldiers examined the result. It was as if a boot heel had been brought down on a beetle. The drivers and the infantrymen worked on ways to communicate and special manoeuvres between them.

They left Vaux pleased at the thought of this powerful new weapon being with them in an attack. Monash could now sit down and plan Hamel with tanks prominent. He took in comments from his battalion commanders, who nevertheless still didn’t wish their infantry to play an inferior role to this new big brother weapon.

Monash thrashed out an arrangement with the flexible Brigadier-General Courage of the 5th Tank Brigade. First, he allowed the infantry commanders to be in charge of his tanks. Second, he agreed that his vehicles would advance level with the infantry. And third, he was willing to risk the tanks coming in close with the infantry behind an artillery barrage; the danger being that the taller tanks, at nearly three metres in height, could be hit by shells falling short.

Monash knew that the tanks would be the main weapon, even if only on the grounds of extreme intimidation. The infantry would back them up by attacking strong enemy positions that the tanks might find difficult to overrun. The soldiers would also ‘mop up and consolidate the ground captured’. This was military jargon for destroying or capturing anything or anyone the tanks missed.

There would be three waves of about 8000 infantry – eight battalions – in total, and tanks: fifteen machines in the first, twenty-one in the second and nine with the ‘mopping up’ infantry.

Monash wanted to use one of his conjuring specialties, flavoured smoke. It would be fired every morning at the proposed zero hour just before dawn to accustom the enemy to it. This incorporated two Monash innovations. First, on the day of the attack, it was hoped that the smoke screen on the flanks and across the entire six-kilometre front, with the left flank on the Somme, would hide the attack. Planes would be used along with the artillery to provide noise to hide the squeal of the advancing tanks. Second, the enemy would have no idea whether the smoke were harmless or deadly gas. They would don their gas masks. ‘This would obscure his vision,’ Monash predicted, ‘hamper his freedom of action, and reduce his powers of resistance.’18

Monash added battery emplacements on the Villers-Bretonneux plateau to hit German anti-tank guns (and tanks if the enemy had any).

Rawlinson received the plan on 21 June. Four days later, Monash felt a little surge of satisfaction and power when Haig approved the first major battle plan of his corps commandership.

Bertangles and the surrounding areas were swamped on 30 June with conferences for the Battle of Hamel. Monash had inculcated a culture of communication and clarity from the moment he created the 4th Brigade in 1914. Now he had control of the entire AIF, his style of environment was developing in the four divisions. Officers and commanders from brigades and battalions who might have been uncomfortable with articulating their thoughts, or lazy about putting them on paper, were rehearsing their speeches or redrafting their ideas to impress, please and fulfil the Corps Commander’s demands. Soldiers and officers who had no idea about the operations of the other arms of the AIF military now had at least a superficial comprehension of all of them. Cross-fertilisation of ideas between artillery, machine-gun, infantry, tank, flying corps, ambulance corps and other officers was rife as they sought to plan their coordination in battle.

Monash held the biggest conference. It lasted four and a half hours. Two hundred and fifty officers attended and sat through the ticking off of his 133 items on the agenda. They ranged over everything from the supply of gas masks and water to reserve machine-guns. Nothing raised and unresolved before the conference was missed. Every key officer had to explain his plans. The others were encouraged to air opinions, opposing views and problems. Monash hated late changes. He wanted to walk way from the meeting with final decisions and proposals fixed and in place.

The conference marked the end of the planning stage. Monash was as happy as he could be that every major or minor issue had been ticked off and tied up.

The battle was set to commence before dawn on 4 July 1918.

Early in July Monash had two VIP visitors. He was happy on the 1st to see Haig, who was impressed by the arrangements and, as ever, praised the new Corps Commander. But Monash protested to Birdwood about Hughes’ plans to turn up the next day. ‘The whole business is extremely awkward,’ Monash said. With three days to go before Hamel, the commander’s mind was immersed in the battle plans, and … ‘Mr Hughes has chosen a time which could hardly be more inconvenient’.19

But Birdwood didn’t need to remind Monash of the continuing plot to replace him. And earlier, Monash himself had implored Hughes to visit the front and see his AIF in action. Reluctantly, the commander had to set aside vital time for the visit.

Hughes came with the deputy Prime Minister, Sir Joseph Cook, the Navy Minister, late in the morning, along with a retinue of pressmen and photographers. They were both unaware of the secret plan for Hamel. Monash decided the only way he could handle the visit and keep abreast of the unfolding of the build-up to the battle was to let them in on the secret plan. This way Hughes became aware of the impact and power of the man whom he was thinking about unseating.

Monash told me his plans for battle [Hughes said]. He was no swashbuckler nor was his plan that of a bull at a gate. It was enterprising without being foolhardy, as was to be expected of a man who had been trained as an engineer and had given profound study to the art of war. Monash always understood thoroughly the ground he was to fight on. Maps lived for him.

Hughes asked him what the battle would cost in casualties.

He had made his plans so that they would be as low as possible [the PM commented, on reflection after the war]. His estimate was about 300, including walking cases. This stamped him, in my mind, as an outstanding figure of World War I. He was the only General with whom I came in close contact who seemed to me to give due weight to the cost of victory. He said: ‘This is what we want to do; this is the way to do it with the least cost in human suffering.’

While Hughes was forming a positive impression of Monash, Bean and Murdoch were powering on behind the scenes to undermine him. Bean had primed White for taking over by lying to him about Monash being on the brink of accepting the bribe to leave the corps to become a full general. Murdoch had built his propaganda about Monash being unpopular with his key officers into a major deception for Hughes’ consumption. The PM until this moment had been set to announce Monash’s replacement by White. But White, honourably, had let Monash know in a letter that he wasn’t supporting the move. He had washed his hands of the plotting and plotters. If Monash agreed to leave the corps, then White told him, the basis for his resisting the Bean–Murdoch scheming would be ‘knocked from under’ him.20

But Hughes had not put anything to Monash by midday on 2 July. He was too busy being thrilled by the meetings and the activity at Bertangles and in the valley beyond it. He lunched with General Hobbs and his 5th Division staff (which included Bruche) and then had a private discussion with Hobbs about Monash. Hobbs recommended him as Corps Commander.

At 2 p.m. Monash laid out the broad Hamel plan and had officers, who were coming to update him, brief Hughes and Cook as well. There was much poring over maps and viewing of the proposed battlefield with field glasses from vantage points.

In the early afternoon, Monash took them to inspect eight battalions of soldiers who were parading in full battle-gear in preparation for moving off to the assembly positions from which, on 3 July late at night, they would march into battle.

Both politicians were caught up in the electric atmosphere of anticipation. Monash invited them to address the troops. At about 5.30 p.m. with the sun throwing long shadows, Hughes mounted a gun carriage in front of a West Australian battalion in full battle dress, and began a speech. ‘There was a major by my side,’ Hughes recalled later. ‘I found the shells flying overhead a little disturbing to the necessary flow of oratory.’ He turned to the major and told him it was too noisy. ‘Couldn’t you let up a little?’ Hughes asked him, ‘I won’t be long.’

‘I’m sorry, sir,’ the major replied, ‘but I can’t do anything about it. That’s the other fellow.’ The Germans were aiming their shells at Monash’s HQ at Bertangles château a kilometre away.

‘Only a little flattening of the trajectory was needed to carry me out of France and into the next world,’ Hughes noted. ‘I finished my sterling oratory in short order.’

‘The stirring addresses,’ Monash wrote, ‘did much to hearten and stimulate the troops.’21

Hughes in particular was excited and in awe of his own power, in theory, over this impressive volunteer force, whose divisions had built reputations and which, as a unified Australian army in all but name, promised much.

Monash seized the moment. When they were alone for a few minutes at about 6 p.m., he told Hughes that he wanted to discuss the crisis over his commandership. Hughes thought it would be better to talk about it ‘later’. Monash wanted to address it then. ‘I am bound to tell you,’ he said, eyeballing the PM, ‘that the arrangement which would involve my removal from the command of this Corps would be in the highest degree distasteful to me. I would regard any removal as a degradation and a humiliation …’

Hughes broke in and, putting his hand on Monash’s shoulder, said: ‘You may thoroughly rely upon your issues in this matter receiving the greatest possible weight.’

It wasn’t enough for Monash. ‘I want you to know,’ he said, ‘I will not voluntarily forgo this command.’22

Hughes would have felt the full impact of Monash’s intent. The commander was on his territory on the Western Front with his men. They were on the fringe of an important battle in Australia’s history, set up by the man Hughes had come to confront. It was a long way from a safe politician’s office in Melbourne. Even an at times brazen, expedient politician like him knew that he could not remove a commander on the brink of a battle. There would be no sacking that day.

Monash would have been aware that he had stepped right into the controversial issue that he discussed in his 1912 essay, ‘The Lessons of the Wilderness Campaign – 1864’: the conflict between a politician and a military commander over who should have the power over whom. Monash held the view that commanders should not be interfered with by politicians bending to ‘public opinion’. In this case, Hughes seemed about to buckle to two journalists who had no claim to any opinion but their own. Monash made it clear to Australia’s prime elected official that he would not accept his order to go. Was it a bluff? How far would Monash go?

Soon after the discussion that never was, Monash penned a quick note to Birdwood, telling him of the Hughes meeting. He added a postscript for White, reassuring him that he trusted him.

After Hobbs’ strong endorsement of Monash at lunch, Hughes made a point of asking the other corps’ divisional commanders and several brigade leaders in private for their opinions of Monash and whether White should replace him. They all favoured Monash. Only the temperamental Gellibrand didn’t give him a strong endorsement, yet even he acknowledged Monash as the best commander in the AIF. Hughes realised that Murdoch had not been straight with him about the feelings of these alleged officers whom he claimed opposed Monash.

That night, Hughes confronted Murdoch and demanded to know the names of the anti-Monash faction. The journalist had no response.

‘Well, I haven’t met a single one of them that thinks as you do,’ Hughes said. ‘They [the commanders] all say the same thing. You say tell me there are men who think the other way [who want White] – where are they?’23

Murdoch remained mute, but was not deflected from his aims. The PM set aside any decision, unless Hamel proved a disaster.

On 3 July, Monash took a few minutes to write a more considered note to White. He repeated his trust in him, but said he thought White’s recent warning letter had been cryptic. There had to be something behind it. Then Monash put aside all the distractions. The timing of Hughes’s visit had proved fortuitous. Monash was relieved that he was still at Bertangles and in charge. Hamel now took his complete attention.

There was one unforeseen problem that needed his full concentration and nerve; otherwise Hamel would be called off. Monash had chosen 4 July, American Independence Day, in deference to a US contingent – 2000 soldiers in eight companies – under his command in the battle. The Americans had been drawn from two divisions of ten training with the British in the areas behind the front. Because of secrecy, it wasn’t until late on 2 July that the American commander, General Pershing, was informed that his men would be in the Battle of Hamel. He objected. No American soldiers had ever fought under a foreign commander. Pershing didn’t want the unusual distinction of being the first American general to allow it. He compromised with Rawlinson, saying he would allow the equivalent of one battalion – 1000 men – to fight. The other thousand had to be withdrawn. The American officers and soldiers were incensed about the decision. They had been in the reserve areas undergoing training and were ready to fight. Monash had to redraw his plans with the assault leader, Sinclair-MacLagan.

During the next twenty-four hours Pershing became unhappier with the idea of any of his troops taking part. Monash was at the HQ of the 3rd Division at Glisy, when Rawlinson notified him by phone of the new decision to pull out all the Americans. It was 4 p.m. on 3 July, barely twelve hours before the battle was set to begin.

Monash was angry. He refused at first. Rawlinson said it had to be done; otherwise there could be an ‘international incident’. Monash was prepared to stand up to his superiors. He had done it to Cox on Gallipoli and in Egypt and to Godley at Passchendaele. Now he told Rawlinson that he had better come to the HQ and explain it all to Sinclair-MacLagan, who was also unhappy with this sudden troop reduction. At 5 p.m. Rawlinson arrived with chief-of-staff Montgomery.

First Rawlinson and then Montgomery insisted that the Americans had to be withdrawn. Monash stood his ground. His dealings with Rawlinson so far had found him flexible to the point of indecision, which might have been owing to his recent years of battle failures. Monash had heard one story about Rawlinson, which confirmed his own experience. At an Army Commanders’ conference with Haig earlier in the war there was discussion about whether to go around a wood or through it. Rawlinson had said at once, ‘Certainly I would go around it.’ After a discussion, the majority thought it best to go through the wood. Rawlinson then said, ‘Certainly, I should go through it.’24

Monash saw some softness in the Army Commander. He picked the moments to attempt to drive through it. This was one of them. He pointed out that his soldiers were already on their way to battle stations. The artillery would soon, under cover of darkness, be arriving at positions in the battle zone and setting up. ‘Even if orders could still with certainty reach the battalions concerned,’ Monash told them, ‘the withdrawal of those Americans would result in untold confusion and in dangerous gaps in our line of battle.’25

Rawlinson became agitated. He spoke again of an ‘international incident’. Monash responded that there could well be such an incident between the Americans en route to the battlefield and their fellow Australian combatants if they were to pull out now. The first thousand Americans taken out had been unhappy. The others could become hostile.26

Rawlinson and Montgomery would not accept this. Monash summed up his position. First, it was too late to pull out the Americans. Second, the battle would have to go on with or without them, or not at all. Third, unless Monash was ordered by Haig to abandon the battle, Monash intended to go on with the original plan. And fourth, unless he received a cancellation order by 6.30 p.m. the battle could not be stopped anyway. As he spoke, the preliminary stages were beginning.

Rawlinson repeated that Monash had to obey Haig’s order.

‘The Commander-in-Chief could not have realised that his order [to withdraw all the Americans] would mean the battle had to be abandoned,’ Monash said.27

Rawlinson’s charm and sympathy for Monash’s position had evaporated. ‘You cannot disobey an order,’ he insisted.

‘But you can,’ said Monash, the lateral-thinking lawyer, putting his case with logic. ‘As the Army Commander, it is open to you to disobey in light of what you know.’

Rawlinson was rattled. ‘Do you want me to run the risk of being sent back to England?’ he said. ‘Do you mean [defying the order] is worth that?’

‘Yes, I do,’ Monash replied. ‘It is more important to keep the confidence of the Americans and the Australians in each other than to preserve an army commander.’28

The comment wouldn’t have endeared him to Rawlinson, who was closer to Haig and very concerned not to make any false moves. His reputation for being a competent commander had received a severe dent two years earlier when on 1 July 1916 he had ordered a disastrous charge at the Battle of the Somme. His miscalculation led to 60,000 wounded and the loss of 20,000 British soldiers killed, the greatest carnage ever in a single day of warfare. Matters did not improve much for the next 139 days of that battle. With this in mind, Rawlinson was cautious. Yet he was riding on Monash’s determination to fight. If the Battle of Hamel were to be a success, Rawlinson would receive needed credit. He was also aware that Monash was a favourite of the King and Haig. Rawlinson might have been senior in rank, yet he knew at these critical moments that Monash’s power was intrinsically greater. With this in mind, Rawlinson let Monash’s firmness and rationale sway him. He agreed to make a decision by 6.30 p.m. Rawlinson couldn’t contact Haig until 7 p.m. Haig agreed with Monash that the Americans should not be withdrawn.

The attack, the C-in-C directed, should go ahead as planned. If it failed, Rawlinson, who had felt the pressure, would manoeuvre to help Bean, Murdoch and Hughes get rid of Monash. If it succeeded, his shaky commandership would be strengthened. Any commander who could plan even a modest victory at this stage would gain considerable prestige.