17

BREAKTHROUGH AT AMIENS

Success at Hamel depended on the start. If the Germans knew the Australians were coming they could position their artillery and machine-guns along the six-kilometre front and pick off the thin line of attackers before the tanks could wreak havoc. At 2.45 a.m. 7000 Australians and 1000 Americans were lying on the grass and crops in the fields on the start line. The RAF night-fighters began their daily swoop over the German lines ahead of the familiar pre-dawn artillery bombardment. The Germans on front line duty put on their gas masks and braced themselves for nothing more than the usual strafing, shells, smoke and interminable noise from their loud opposition across the low-gradient valley.

There was one difference on that fateful 4 July 1918. A thick fog, rare for the middle of summer, descended on the area like a huge crocheted blanket. This made it difficult for commanders and officers to make observations. Guidance was tougher. But the fog had the overriding use of making the attack more of a surprise. With the noise drowning the sound of the tank movements, by the time the Germans knew they were being invaded, the vehicles were just metres away and emerging from the fog like monsters. Those Germans who didn’t freeze were flattened, chased or fought by the tanks and the supporting infantry.

There were some pockets of resistance from well-fortified machine-gun emplacements and artillery, which belatedly defended. But it was a rout. The Battle of Hamel, on which Monash had staked so much, was over in just ninety-three minutes. It was a modest encounter in the context of the war, but the rapidity of the victory, with much gain and little cost, meant an immeasurable lift in the confidence of the Australian Corps and the entire Allied command. The British Tank Corps at last had something to celebrate. This precedent would be the model for every British attack using tanks for the rest of the war.

The Australians, in their first action as a corps, had won a near-perfect victory. And Monash revelled in the sense of harmony achieved by his infantry, the Tank Corps, the Royal Artillery and the RAF. It had worked the way he planned it and always dreamt perfectly prepared battles should be. He counted 800 casualties in his force, but most were walking wounded who would see action again. Monash’s aim to have the machinery protect the infantry could not have been better executed. But in this conflict even the tanks came through far better than expected and better than they ever had before. Only three were put out of action, but even they would be repaired to fight again.

The Australians were happy to collect 1500 prisoners, a huge haul for such a small battle. Monash was pleased that perhaps half of them were wearing gas masks, which was evidence that his smoke trick had worked. Another 1500 Germans were killed or made casualties. The booty – always a useful boast in war – was impressive. It included two field guns, twenty-six mortars and 171 machine-guns. Territory gained – another military measure of success – was four times that by any other force of a division or less in 1917, when the last British offences happened.

Another aspect of Hamel was the American involvement. It was the first time they had been in an offensive battle in the war, and Monash was keen to increase this link.1 There were no negative repercussions from his decision to insist on their fighting despite their Commander-in-Chief ordering them out. In fact, Pershing revelled in the after-glow of the Hamel victory, and the men who fought had a status that other US divisions envied.

Monash’s other notable inclusion, apart from strong support for the much-maligned tank, was the use of planes to drop ammunition to the machine-gunners. It required two men to carry a box holding 1000 rounds, which one gun could fire off in less than five minutes. It was heavy, dangerous work for the carriers, often under fire. Now that risk to soldiers had been reduced. Time had been saved; efficiency was increased. It was a small advance. Yet when put in the context of how it increased the proficiency of machine-gun use as an offensive weapon – another Monash edict – his faith in the technology and his capacity to incorporate it effectively were increased. Everything had worked, from the use of smoke and every latest artillery projectile to machine-guns and planes.

Monash and his force had set some sort of standard, recognised by the British Army, which sent out a staff brochure on the operation to all officers. This brought him much kudos, but he was more interested in his survival as a commander. A clue came from a long, effusive telegram from Hughes who, after visiting Bertangles and the AIF, had moved on to an Inter-Allied War Council meeting at Versailles outside Paris. The telegram included a message from Haig to Hughes: ‘Will you please convey to Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash and all ranks under his command, including the Tanks and the detachment of 33rd American Division, my warm congratulations on the success which attended the operation carried out this morning, and the skill and gallantry with which it was conducted.’2

This was the sort of endorsement Monash wanted. He hoped Hamel had bought him time. Yet he would not rest on this achievement. Even late on the day of the victory, he ordered Sinclair-MacLagan and Hobbs to start patrolling into enemy territory. In reality it was raiding. While adhering to the doctrine of the limited objective, whereby territory was gained and held, Monash never stopped planning aggressively. Even as the tanks were bringing back the cheering, waving soldiers, including the wounded, he was stretching over his maps in the war room at the château. Some of his officers might have been opening champagne and unwrapping fat cigars, but Monash, smoking a pipe, was busy with the tireless Blamey putting down coloured paper and using a cue to move miniature infantry markers.

Monash was a realist. He sensed that the near-faultless Hamel success had been due mainly to his strategic skills. But its completeness was also partly because of the fatigue and battle-weariness of the Germans, despite the massive reinforcements that had all now arrived from the Russian Front. The enemy was stunned and defending. Now was the time to shake up their defences even more.

The next day, he asked Rawlinson to reduce his expanded front of eighteen kilometres. It was too wide for his four divisions, even on rotation, to maintain.

Some of his brigades needed a long rest. Monash began to visit his men, inspiring them to be prepared for more hard work and battles. Everywhere the Rolls-Royce with the prominent Australian flag appeared, Monash received spontaneous applause and cheering. Ever since Gallipoli his popularity had increased. There was always a good response for chatty, ebullient Birdwood, or the muscular leadership of the inspiring Pompey Elliott, or the fearless drive of Cannan. But Monash’s reputation had been built on a solid foundation of training, planning, detail and performance. His attention to the little things that affected every soldier filtered down to them. His preference for control and decision-making from the expanding engine room at HQ rather than being seen at the front had developed a mystique based on solid, reliable performances from the ‘old man’. The name ‘Monash’ was now associated not only with a strong organisation but also with winning. Nothing would please him more than for it to be equated with victory. Furthermore the way he articulated the soldiers’ success and what it meant in the bigger scheme of things had also endeared him more and more to every man in the corps. The men at the front appreciated his directness. He wasn’t promising girls and beer but guns and batteries that still had to be taken on and defeated.

Monash now read the mood of his men with more certitude than a latter-day politician reads electronic polling on an electorate’s mindset. He wanted to fuel the AIF’s huge and hungry appetite for the fight. One way was to push Rawlinson and Haig for the return of the 1st Division. The AIF spirit was on such a high that he wanted to build on its morale by having all five divisions together. Monash was confident that if he could arrange this, then he could create a huge psychological advantage and sense of invincibility in the force. This feeling was important to his leadership. He had studied the attitudes of Napoleon and Wellington to the sense of being winners. This created an aura of invincibility, which built the confidence of its members and destroyed the morale of the opposition. Hamel had been the first step. Monash’s aim, like that of Wellington, was to build the feeling that no matter what the position on the battlefield, his force could always find a way to win. His own interrogation of German prisoners confirmed that the enemy was already more than wary about tackling the Australians. One of Monash’s aims, indeed themes, in discussions with officers and commanders was to build on this belief, even if it meant bluffing the enemy.

After repeated requests it was agreed that the 1st would join the rest of the Australian Corps and be in reserve for the start of the next major engagement.

The result at Hamel was firming up the attitudes of others, too. Monash received a letter from White that confirmed his last message was indeed enigmatic. Now White made it clear that his friends – Bean and Murdoch – were not conspiring at his ‘suggestion’ or with his ‘approval’. This did not mean that White didn’t covet the Corps Commander’s job. He was just making clear to Monash that the frenetic, persistent plotting had nothing to do with him. But White still hadn’t confronted his friends. He had not yet told them he was not a competitor for Monash’s position.3 Then again, he was now in London away from the action, and had not had a chance to speak to the peripatetic Murdoch and Bean since before Hamel.

White’s distancing of the himself from the conspirators, along with the positive reaction from Hughes and Haig, and the news that the French Premier Clemenceau was on his way to congratulate the Australians, all buoyed Monash on 6 July when he met with Murdoch at Bertangles. His guard down and his confidence up, Monash told the journalist what he had not been able to write earlier: when he had won battle honours, he would be happy to take up the administrative role in London.

This gave the plotters hope. But Monash did not specify what battle honours would satisfy him. Would he be content with another Hamel and then leave? Or would he want to push on into 1919 and be part of the actual victory, if it were to come the Allies’ way?4

When Murdoch told Bean what was said at the meeting, the correspondent urged the journalist to advise Hughes not to give Monash time. But the PM was not ready to oppose him straight after Hamel. White, too, was in a different mood. His refusal to lobby against Monash was justified. In a face-to-face meeting on 12 July, White attacked Murdoch for ‘impropriety, ignorance and dangerous meddling’.

The journalist didn’t like the rebuke, especially after Hughes’ rebuff over his concocted sources. But these minor setbacks had not diminished his view of his role as a power-broker who would get his way. From that moment, Murdoch was not a White supporter any more. He now fell back on a jingoistic argument and viewed White as politically naïve and ‘subservient’ to England. White had been the plotters’ choice because he had not been the British selection. But now that he showed no inclination to unseat Monash, Murdoch had branded him an English lackey. It was a weak argument. The Bean–Murdoch position now seemed brittle, but they were nothing if not tenacious.5

Bean thought differently from Murdoch, although his aims were the same. Unlike Murdoch, who saw issues in terms of politicking and how he could manipulate the main players, Bean viewed everything in terms of what was right or wrong, as interpreted by him, in historical terms. But after Hamel he became desperate and was carried away with his self-importance. He wrote to White imploring him to step forward and ask Hughes to appoint him Corps Commander. Bean saw it as perhaps ‘the major job in his [Bean’s] life’ to ensue that Monash was made administrator in place of Birdwood and that White got the corps.6

Despite his change of heart over White, Murdoch knew that no one else was a suitable choice after Monash to be the Corps Commander. This caused him to persist too, trying to cajole Monash with more inducements of grandeur. But again he misjudged his man. Murdoch puffed up the London desk job more, saying that the PM was seeking someone to take over ‘much of the semi-political, semi-national, economic and financial character’ of the work. Yet Monash never saw himself as a politician or even an economist. The position did not challenge him. He was a soldier first, and not a politician second or third.7

Murdoch also thought he was teasing Monash by telling him that a most important immediate post-war position would await him. Monash knew the job to be repatriation, but it was the last thing on his mind after Hamel. There was much to do on the battlefield before any such operation. The correspondence shows that Monash for the first time was beginning to toy with his tormentors. He kept his communication with Murdoch friendly and open while still deftly closing off all options.

Victory against the two would-be commander-makers, if attained, would be as sweet as that over the Germans. At least the latter’s attempts to get rid of him had not been personal.

Monash was pleased to welcome the French Premier, the cultured seventy-six-year-old Georges Clemenceau, on 7 July. He was the most important Allied political figure, and had a few months earlier managed to persuade other government heads to place Ferdinand Foch as sole military commander, ahead of Haig. Monash admired the journalist and statesman Clemenceau for his single-minded determination to defeat the Germans and his declaration that he would wage war ‘to the last quarter hour, for the last quarter hour will be ours’.

Monash assembled a large contingent of the soldiers who had participated at Hamel, and who were resting at Bussy. He was looking for every means to keep his fighters buoyant and willing. He couldn’t think of a better person – the top representative of the country for which AIF soldiers were primarily fighting and dying – to speak to them. Monash was aware that Old Georges, one of France’s foremost political writers, and a lover of the Impressionists, especially Monet, would himself make a deep impression with his heartfelt words.

He addressed the Australian volunteers in English, speaking about the attitude to freedom in Australia, England, France and Italy.

That is what made you come [he said]. That is what made us greet you when you came. We knew you would fight a real fight, but we did not know that from the very beginning you would astonish the whole continent with your valour … I shall go back [to Paris] tomorrow and say to my countrymen: ‘I have seen the Australians; I have looked into their eyes. I know that they, men who have fought great battles in the cause of freedom, will fight on alongside us, till the freedom for which we are fighting is guaranteed for us and our future.’8

It was the right stuff, especially as the AIF was expected to be the spearhead of future battles. Every soldier understood why Clemenceau was nicknamed Le Tigre. It was just the sort of inspiration Monash was looking for as his eager troops waited for more and bigger challenges.

But Foch and Haig restrained him. Commanders who had made disastrous decisions to attack when they should have planned better were now timid when they should have been bold. Many failures, and public opinion moving against them, were having an impact on their decision-making.

For the rest of July, Monash’s divisional generals had to be content with nibbling at the enemy’s forward positions. Rosenthal led the way with his 2nd Division, which advanced the Australian line by one kilometre opposite the east of Villers-Bretonneux by taking Monument Wood. It had been thick with Germans. This advance rid that part of the town from the fear of being machine-gunned by the enemy, who could peer into the streets.

By early August, Foch and Haig concluded that there would be no more big German pushes into Allied-held territory in the Somme Valley. The enemy was thought now to be purely on the defensive. The German Second Army, astride the river, was now the target and ripe for a massive attack. Monash began drafting a battle plan based on the strategies and tactics at Hamel.

He had not been satisfied with the French XXXI Corps of General Debeney’s army on his right or southern flank. He was at pains to explain that it wasn’t because the two forces didn’t get on. A strange common vernacular – it was dubbed Francalian – had even developed between them, and they fraternised well. But Monash was worried by the real language differences, which counted in the heat of battle, the gap in the style of fighting tactics and the ‘divergent temperaments’.

‘The French are irresistible in attack as they are dogged in defence,’ he said diplomatically, ‘but whether they will attack or defend depends greatly on the temperament of the moment. In this they are unlike the British or Australian soldier, who will at any time philosophically accept either role that may be prescribed for him.’

In other words, the British and Australians were better disciplined and drilled, making them more reliable under pressure. Besides that, even if Monash applied his rusty French in an attempt to charm his hosts, he couldn’t get them to push back the Germans in the French force’s allotted territory. After Hamel, the front line had a nasty bump in it where the Australians had pushed forward, but the French had stayed put. This made the AIF’s right flank vulnerable. Monash knew they weren’t weak, but he was baffled by their intransigence. He wanted that front line bump free and straightened out. But because of a different policy, or sheer French bloody mindedness, he worried about them in forthcoming ‘much more serious undertakings’. His concerns were exacerbated when he visited Field Marshal Pétain.

‘If the Boche attacks,’ the French leader told him, ‘we’ll fall back.’9

Now Monash feared he would be vulnerable on both flanks if the French were there. He asked Rawlinson for and received Currie’s Canadians on his right instead of Pétain’s French. Now he had a worry only on his left flank at the Somme with the British III Corps led by General Butler on the other side of it.

Again, Monash was nervous about the British commanders, whom he did not think were up to the difficult task north of the river. But there was nothing to be gained by airing this. Instead of complaining about Butler and his staff, he told Rawlinson he wanted his force to be ‘astride’ the river. Much against his will, Monash was forced to wait until the battle to see whether the problem unfolded as predicted.

There were other problems out of Monash’s control in the build-up to the AIF attack. Although the Germans were not attempting infantry retaliation, they had no compunction about drenching the AIF front with mustard gas, fired by their artillery. On many nights, the Germans would think nothing of expending 10,000 shells on the half-ruined and partly deserted Villers-Bretonneux or in the woods surrounding the town where the Australians sheltered.

The soldiers dreaded mustard gas. In its pure form this chemical weapon was colourless and odourless. But the Germans had given it a whiff by adding a mustard-smelling impurity. It increased fear. When that smell hit an area, soldiers were alarmed. Its symptoms and consequences could be horrific. It often began as an itchy skin, which in a few hours led to blisters. It made the eyes sore; the eyelids would swell. In mild cases it lead to conjunctivitis; in some it caused blindness.

Mustard gas had a rotten habit of not going away. The smell might disappear in the early morning, but when the warm August sun rose, invisible or brown-coloured pools of it, scattered over several kilometres, would form a vapour and strike unsuspecting soldiers. On hot days, concentrations were higher. Soldiers who inhaled it more often than not had bleeding and blistering in the windpipe and lungs. An end result could be pulmonary oedema, or even cancer, which could strike early or take decades. (Many an ageing digger would complain of lung problems that began with mustard gas. If it didn’t get them on the battlefield it struck them down over time.)

The French, not the Germans, first used gas – in August 1914. They fired tear-gas grenades (xylyl bromide). But the Germans were first to study the development of chemical weapons and to use them in strength. They began in the capture of Neuve Chapelle in October 1914 with a formula that caused sneezing fits. The Germans often found French soldiers convulsed and clutching handkerchiefs in the trenches. It gave the Germans hope that they could win the war by making all their enemies sneeze themselves to capitulation or death. Inspired by the French experience in the early spring, they loaded up their howitzers with this gas on the Russian Front at Bolimov in the middle of winter. But there was no sign of Russian soldiers grabbing their noses or making violent head movements. The gas had failed to vapourise in the freezing conditions. Disappointed that they couldn’t win the battle of the sneeze, the Germans used the first poisonous gas – chlorine – in April 1915, at the start of the Second Battle of Ypres. It choked its French and Algerian victims, destroying their respiratory systems. The British were quick to condemn the Germans while rushing to develop their own chlorine bombs, which were to be delivered in artillery shells.

The Germans stayed in front by developing something even more insidious than chlorine: phosgene. This horror was subtler. It caused less coughing and choking. But more of it was inhaled. Its effect was delayed. Apparently healthy soldiers would collapse two days later. The French used prussic acid to make nerve gas, which they introduced now and again. Mustard gas, the worst of the lot, was used first by the Germans against the Russians at Riga in September 1917.

‘This form of attack,’ Monash recorded, ‘and the constant dread of it, made life in the forward areas anything but endurable.’10

In the lead-up to the Battle of Amiens, the diggers scrambled to put on their gas masks as soon as a bombardment hit to avoid being a casualty before the whispered big battle began.

Haig and Rawlinson had considered a massive counter-attack in May but were not confident about the unconvincing plans on the table. They abandoned them after the big German offensive on 27 May. The two discussed it again in June. But still no thoroughly thought-out plan was put up.

That all changed at Hamel. Monash’s ‘win’ was based on an unprecedented harmonious use of tanks, aircraft, artillery and ground troops. Just at a moment when the Allies needed to be shown the way, Monash’s solid ideas emerged out of the pack of concepts from twenty-five commanders under Haig and proved successful. From 1 July – three days before Hamel – for the next three weeks, Monash pushed hard for the instigation of his blueprint for a massive counter-attack, based on the tactics he used at Hamel. He had a meeting every day from 4 July with Rawlinson. This veteran general was now more willing to consider the ‘Dominion’ commander’s plans. So was Montgomery. Monash discussed his work in progress and urged them to take the initiative now while the enemy was vulnerable. The day after Hamel, Monash was convinced that he could drive through the German defences eight kilometres or more if he had that promised Canadian support on his right (southern) flank. It was not then set in concrete. There was much hard work to do before Rawlinson would be confident about any huge counter-attack.

At a meeting on 13 July, Montgomery asked for some specific proposals.

‘Reduce my front [to further concentrate his Australian force], return 1st Division [from Flanders in the north assisting the British at Hazebrouck] and use the Canadians [on his southern flank],’ Monash responded.

He again spoke to Rawlinson and Montgomery at length about the overall scheme on 14 July. He said his position ‘was analogous to an inventor who conceives a new scientific idea, and who talks it over with his colleagues and friends. They all make suggestions, which are discussed, some being adopted and others rejected, so that ultimately the new idea takes a definite form and substance.’11

Monash’s ‘friends and colleagues’ were his staff, divisional commanders, Haig, Rawlinson and Montgomery. He redrafted it for several weeks, incorporating all their useful contributions (apart from a few key points that he would argue in future meetings) until his plan had ‘form and substance’ and broad consensus – a critical point in coordinating a military operation on this scale.

Monash fine-tuned every aspect of the battle from the use of tanks, aircraft and artillery to deception methods, such as smoke and noise screens. His request to Montgomery for the 1st Division was motivated too by his fervent desire to unite and direct all five Australian divisions in a battle for the first time. Monash was proud of the courage, fortitude, resilience, endurance and fighting abilities of his men and all the Australian force that invaded Turkey in 1915. Then he and his fellow commanders had been handicapped by poor planning from the British High Command, a very narrow beachhead on which to fight and a severe lack of resources and support. Now Monash would be given all the resources he wished. He had a much wider front on which to operate. And he had what he considered the best fighting force in the war to direct as the arrowhead for the Allies.

Monash had instigated the recognition and commemoration of Anzac Day. Now he was determined to advance the sense of nationhood an important notch beyond Gallipoli. He wanted victory. The move towards it would begin by presenting the German Army with its biggest surprise of the war.

On 15 July, Monash briefed Rawlinson in detail about his ‘counter-offensive’ plan, and next day presented it to Haig when he visited Bertangles. It focused on the role of the AIF, but incorporated a broad strategy for four attacking corps, running from left to right (or north–south) facing the enemy: the British, the Australians, the Canadians and the French. The Australians and the Canadians would form the point of the arrowhead. The British on their left and the French on their right were meant to guard the flanks of the main attacking corps.

Monash had not been part of any failed plan on the Western Front apart from the battle of Passchendaele. He was keener than anyone of Haig’s army or corps commanders to seize the chance to smash through the German lines. His aggressive attitude, based on his confidence in his own detailed planning and intelligence, saw him emerge in these critical days of mid-1918 as the most forthright leader in Haig’s pack.

Haig’s position had been strengthened in March 1918 when he helped dislodge his superior, French General Robert Nivelle, Supreme Allied Commander on the Western Front, in favour of a friend, another French general, Ferdinand Foch (who became Supreme Commander of all Allied forces). Haig and Foch proved an amicable combination. The Scot got his way much more than he had under Nivelle. He could now exercise full tactical command of the British armies (including the Australian and Canadian forces), which Nivelle had never allowed.

Haig’s brutal reputation had been tempered by his role in helping to stop German offensives of March and May. Monash was giving an enormous further boost to Haig’s status. Mindful of the King’s appreciation of Monash, and his capacities as a thorough, brilliant strategist, Haig was now paying him more attention than ever.

Monash’s plans were also attractive for another reason that would enhance Haig’s image and modify his reputation as a butcher. They were structured for a minimum of casualties. That was a novelty in July 1918.

Haig sat on the château’s piazza and read this most recent blueprint for victory against the Germans. He pronounced it ‘very good indeed’ and made some other favourable remarks without any suggested changes. The British commander reminded Monash that he had to be patient. He also mentioned that he couldn’t ‘authorise it without consulting Generalissimo Foch’.

Monash asked how long that would take. Haig thought two weeks, and said he was going to take a break ‘in Touquet to play some golf’. Haig suggested Monash also take some long overdue leave but in London rather than Paris. It would be easier to contact him. Monash thought he would go. Haig told him to ‘tell Henry [Rawlinson] I recommend it’.12

Monash suggested they both put out press releases concerning their plans to take leave. This would deceive the Germans into thinking that no counter-attack was being contemplated.

Monash sent his written plans to Rawlinson later on 16 July. The Army Commander, who was admired more for his fluent French and skills as an artist than his capacities as a strategist, submitted formal proposals to Haig the next day. They incorporated his own ideas and an ‘edit’ of Monash’s master-plan for an AIF thrust, with refinements for the other three corps.

Rawlinson didn’t like Monash’s ‘artificial’ boundary between the British corps and the Australians. Rawlinson put back the Somme River as the boundary. He also put the first objective ‘finish line’ in the attack short of the German artillery. Monash wanted to take the artillery in one hit. Past experience taught his command that not taking the artillery left the advancing force vulnerable to the enemy regrouping and using it against them.

Monash had ignored Rawlinson’s plans for the cavalry, believing that horses were superfluous in the planned encounter except for ‘mopping up’ after the main conflict. But Rawlinson was still rooted in warfare techniques from the previous century. Besides, Haig insisted that the cavalry be in the fight. There was nothing like the odd charge on horseback to spice up a battle. Monash thought it wasteful and a nuisance to have horses and tanks attacking together. The equine speed was considerably faster than that of the crawling, creaking armoured monsters. But it didn’t matter. Haig wanted them in, so they were in.

Rawlinson agreed with Monash’s request to reduce his front from seventeen kilometres to less than seven kilometres. He also allowed the Australian 1st Division to join the corps from Flanders, where it had been fighting in. This was an enormous boost for Monash and the AIF.13

On 18 July news came through of a successful counter-attack by the French led by General Mangin ninety kilometres away to the southeast at Soissons, and supported by France’s Sixth Army. They went in with 2000 guns, 1100 aircraft and 500 tanks in support of twenty-four divisions. They took 1500 prisoners and 400 guns. Coming two weeks after Hamel, this success seemed to confirm German vulnerability, and it speeded the Allies’ plans.

Haig approved them on 19 July. Two days later, Rawlinson called a meeting of all the key commanders for this new offensive – to be known as the Battle of Amiens. It was set for 8 August.

The rendezvous location was a pretty village of Flexicourt on the Somme, obscure enough for there to be little fear that an enemy spy would notice the unusual, pretentious motorcades arriving on the lawn in front of an elaborate white mansion. It had been commandeered for the beautiful, still summer’s morning by Rawlinson. The black and red flag of the Fourth Army Commander hung over the mansion’s entrance. Monash, punctilious as ever, was looking at his watch as he arrived in a Rolls-Royce with the Australian flag prominent. General Currie, the Canadian Commander, rolled up, his flag flying too. He was following General Butler of the British III Corps, General Kavanagh of the cavalry and then senior representatives of the Tank and Royal Flying Corps.

Rawlinson outlined the complete army plan, which was largely Monash’s creation. The commanders sorted out the broad plans for the attack. Rawlinson imposed no limitations on them for what they did within their own boundaries, as along as they met their objectives and didn’t let the other corps down. Monash’s aim was to advance eight kilometres.

Currie was happy with his plans, which Rawlinson had refined after he had seen Monash’s proposals. Tanks were an additional item in the Canadian operation. Monash didn’t think he had enough of them after his unprecedented success with them at Hamel. Rawlinson increased his quota to nearly 500.

Monash was concerned about the confusion surrounding transmission of urgent messages from the front. There was no certainty about finding a phone terminal, and even then messages were transmitted too slowly for an effective response by HQ. There was also a problem with the speed of transmitting messages up the chain of command from battalions to brigades and divisions. By the time messages reached HQ – often more than twenty minutes later – the battle conditions most likely had changed. Responses would be late. Monash proposed the use of planes for reconnaissance and message transmission. He was granted nearly 800, each one carrying a pilot and observer, from the No. 3 Australian Squadron. Monash expected to cut the time he and his staff received messages and intelligence from the front to something around ten minutes.

The corps commanders were happy with their 2000 artillery pieces. Yet there was concern about the numbers held by the enemy. Monash objected that Rawlinson had not approved of German gun positions being a target in the first phase of the three-phase attack, which would cover three kilometres. The Australian troops had complained that in earlier battles, if artillery was not taken or smashed in the first phase, the Germans retreated with it in the pause before the second phase and used it against them later. Rawlinson consented to this change.

Monash was also unhappy to see that Rawlinson had made the Somme a northern boundary for the Australian Corps operations. Monash wanted at least one Australian brigade (4000 soldiers) over the Somme so that he controlled both sides of the river. He thought it was an unnecessary boundary.14

‘It creates a divided responsibility [between him and the British commander in charge of the corps north of the river],’ he told Rawlinson. Monash suggested that this would make it harder for him and the British commander to cooperate. His real worry was Chipilly Spur, a rocky ridge beyond some terrace meadows just north of the river, which was stoutly defended by Germans because of its vantage point. The Somme meandered as a boundary to those somnolent fields, then encountered the steep wood-covered slope, which ran for several kilometres. The Germans would find easy targets among the Australian troops moving forward in the meadows as well as being tough themselves to dislodge from their dominant position.

The spur offended Monash’s obsessive dedication to ironing out all problems before any attack. It continued to dog him. There had already been fierce fighting there. Monash wanted to command the attack on Chipilly, fearing that his left flank would be exposed if the British couldn’t take it. Butler objected.

Rawlinson supported Butler, saying that this target remained with the British III Corps. Monash was uneasy. He suggested that Butler had to take Chipilly. He had to keep attacking until he secured it. This suggestion caused some tension, but Rawlinson agreed. A disgruntled Butler was under instruction now to make Chipilly a priority.

Monash was still not happy. He had little confidence in Butler and his staff. During a break, Monash told Sinclair-MacLagan to prepare a defensive flank in case the British failed. He knew how fluid matters could become once a conflict began. He would continue to urge that he be given control of the operations north of the Somme.15 For the moment he had to be content with his prescribed boundaries marked to the north by the river and the south by the railway. The country – the Australian Corps battleground – in between was flat, open and dotted with woods and villages.

At the end of the meeting, Monash obtained Rawlinson’s approval for leave in London as long as he was ‘prepared to return at very short notice’. Rawlinson also arranged that Monash would receive a coded phone message via the War Office in London when he had to return.

Monash took off from Bertangles on Tuesday 23 July, picking up a boat that took him from Boulogne to Folkestone, where a car ran him to the Prince’s Hotel, London, in time for an evening with Lizette.

On 24 July they lunched at his hotel and spent the afternoon shopping. On 25 July, Monash sat for Australian painter John Longstaff. At night he and Lizette went to the theatre to see Naughty Wife. They went again on 26 July to see Going Up. It was light relief that helped him escape the hell across the Channel.16

Monash visited the War Office each day. He did press interviews, which he considered important in putting an Australian perspective on events. The War Office had underplayed his corps’ contribution. It didn’t want Dominion forces to be perceived as bearing the brunt of the fighting or, more bluntly, as cannon fodder. It was feared that Hughes might feel it necessary to pull Australia’s armed forces out of the conflict if he thought they were overexposed. Nonetheless, Monash felt compelled to fly the flag for himself and his men.

Time was swallowed up fast. He accepted an invitation to attend the opening of Australia House on the Strand on 3 August, but never made it. After just five days of comparative bliss the War Office rang his hotel late on Sunday 28 July to give him the coded message. He could have done with a month’s leave, but at least he had had a break from the constant grind, misery and din of war, and the interminable demand for decisions.

Monash said goodbye to Lizette in London on Sunday night. He preferred not to take the then risky option of flying. Instead, the next morning a car picked him up just before dawn. He was driven to Dover, where a destroyer was waiting for him at 7 a.m. It took him to Boulogne. A car then drove him the 130 kilometres to Bertangles, where he lunched with his staff and division commanders.

On 31 July, Monash called for a conference with his divisional commanders, and asked for their plans. They were put to the meeting for discussion, comment and questions. Monash, as usual, dominated the conference without taking it over. He encouraged criticism on even the minutiae.

Haig dropped in to Bertangles, giving words of encouragement to all the divisional commanders. He went out of his way to express how much confidence he had in Monash. At this conference, they worked out the deployment of the field and heavy artillery, the tanks and armoured cars, and the Cavalry Brigade, which Haig had repeated must be used. They also covered the use of infantry, the methods of attack and the tactics.

On 1 August, Monash summed up the meeting in memos sent to all the divisions, and they covered many of the outstanding queries. Blamey remarked later that he doubted that any commander in any major battle in history would have matched his leader for preparation. ‘Elements of the meticulous, careful forethought reached every member of the AIF,’ he noted, ‘and gave them even greater confidence and inspiration.’17 Bean expressed a similar sentiment, with the benefit of hindsight. ‘… the range and tireless method of his [Monash’s] mind were beyond any that came within the experience of the AIF,’ he wrote. ‘His men went into action feeling, usually with justification, that, whatever might lie ahead, at least everything was right behind them.’18

The Australian 1st Division was transferred from under the command of the British Second Army to join Monash’s Corps. It had been rushed down from Flanders early in April when Amiens was threatened during the first battle of Villers-Bretonneux. The 1st was then hurried back to help the hard-pressed British line near Hazebrouck. Now the division mustered for something big and still secret. As the soldiers travelled south by train, they could only make guesses based on rumours as to what it would be. They were pleased to be joining Monash and the rest of the Australians. They had heard of the success at Hamel and were expectant about joining a far bigger campaign. These experienced soldiers were disappointed to learn as they arrived at Amiens that they would be held in reserve for whatever was about to unfold.

The movement of two Canadian divisions (about 30,000 troops and equipment) to a point south on Australia’s right flank – on the other side of the Amiens–Nesle railway line – was kept as secret as possible. The reason leaked everywhere by HQ was that the Canadians were relieving the Australians so that they could have a long, well-earned rest after their years of hard work at the front. There was no hint that the Canadians were joining them for a massive attack.

Yet it was impossible early in August not to make German intelligence suspicious as brigades began intricate manoeuvres in preparation for the attack. The Germans decided on a raid in the area into which the Canadians were moving and replacing Australian brigades.

On the night of 4 August, the 4th Australian Division’s 13th Brigade was spread over a five-kilometre front. If it occupied the front-line trenches the Germans would be alerted. There was no option but to defend its area with a series of small, isolated posts. One of these posts was on the road to Roye beyond the southernmost part of the area occupied by the Australians. The Germans raided it. A sergeant and four soldiers were captured. They were taken behind lines and interrogated. The Australians refused to disclose anything but their names and units, which was their right, if they could withstand the pressure.

Monash and his staff were not aware of the bravery of the captured men. The command could only hope that they had held out or that they knew nothing of the imminent plans. It decided to leave the 13th Brigade where it was and not to displace it with Canadian troops until the last minute before the Allied attack. Monash planned to replace this brigade of the 4th Division with one – the 1st Brigade – from the incoming reserve of 1st Division. It arrived at night on 6 August, just in time to be slotted into the order of battle of 4th Division under General Sinclair-MacLagan.

Also arriving after dark for the 4th and 5th Divisions were eighteen tanks stuffed to the brim with rifle ammunition, Stokes mortar bombs and petrol. They rolled and squealed into a small plantation a kilometre north of Villers-Bretonneux, from where the massive attack would be launched.

The strike was set for the morning of 8 August 1918 at 4.20 a.m.

It was a day of tension on 7 August. While it was not all quiet on this section of the Western Front, there was a definite lull. The Germans, like the Allies, had new listening devices for tapping telephones. Monash ordered the restricted use of telephones, especially in areas closest to the enemy. This meant that commanders and staff had to walk or hop in their cars or on to horses in order to make final inspections and directives.

‘A strange and ominous silence pervaded the scene,’ Monash noted. ‘It was only when the explosion of a stray shell would cause hundreds of heads to peer out from trenches, gun-pits and underground shelters, that one became aware that the whole country was really packed thick with a teeming population carefully hidden away.’18

At night, Monash’s artillery commander, Brigadier-General Coxen, made his last round of battery positions – a dangerous job. The Germans were firing shells at random into the area. Coxen reached the plantation where the tanks, covered with tarpaulins, were sitting. He and the soldiers protecting him went to ground as the last of a dozen shells whistled towards them. It fell into the centre of the tanks. They exploded. A cloud billowed into the area. The Germans, unaware that they had hit an important spot by chance, then turned a concentrated artillery barrage on the plantation. In twenty minutes, fifteen tanks and their valuable cargoes were destroyed.

Coxen rushed back to Bertangles to inform Monash that the fire was an accident. The enemy was unlikely to have had prior knowledge of the pending strike or the tanks that would be in the front line. Monash had the tanks and stores replaced. He would go on with the attack as planned.

On the afternoon of 7 August, he had a message sent to all of the 166,000 Australian troops in his corps. It read:

TO THE SOLDIERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN ARMY CORPS.

For the first time in the history of this Corps, all five Australian Divisions will tomorrow engage in the largest and most important battle operation ever undertaken by the Corps.

They will be supported by an exceptionally powerful Artillery, and by Tanks and Aeroplanes on a scale never previously attempted. The full resources of our sister Dominion, the Canadian Corps, will also operate on our right, while two British Divisions will guard our left flank.

The many successful offensives which the Brigades and Battalions of this Corps have so brilliantly executed during the past four months have been the prelude to, and the preparation for, this greatest culminating effort.

Because of the completeness of our plans and dispositions, of the magnitude of the operations, of the number of troops employed, and of the depth to which we intend to over-run the enemy’s positions, this battle will be one of the most memorable of the whole war; and there can be no doubt that, by capturing our objectives, we shall inflict blows upon the enemy which will make him stagger, and will bring the end appreciably nearer.

I entertain no sort of doubt that every Australian soldier will worthily rise to so great an occasion, and that every man, imbued with the spirit of victory, will, in spite of every difficulty that may confront him, be animated by no other resolve than grim determination to see through to a clean finish, whatever his ask may be.

The work to be done tomorrow will perhaps make heavy demands upon his endurance and staying powers of many of you; but I am confident, in spite of excitement, fatigue, and physical strain, every man will carry on to the utmost of his powers until his goal is won; for the sake of AUSTRALIA, the Empire and our cause.

I earnestly wish every soldier of the Corps the best of good fortune, and glorious and decisive victory, the story of which will echo throughout the world, and will live forever in the history of our homeland.

At 3.30 a.m. on 8 August, Australian Gunner J. R. Armitage lay in readiness for the attack. He wrote in his diary:

It was utterly still. Vehicles made no sound on the marshy ground … the silence played on our nerves a bit. As we got our guns into position you could hear drivers whispering to their horses and men muttering curses under their breath, and still the silence persisted, broken only by the whine of a stray bullet or a long range shell passing high overhead … we could feel that hundreds of groups of men were doing the same thing – preparing for the heaviest barrage ever launched.20

At 4.00 a.m. the only noise now came from Allied planes droning over the enemy as a cover for the menacing sound of those squealing tanks that kept inching forward. Monash was woken by one of his aides, Major Berry. He dressed, read final reports and then walked into the Bertangles grounds. At 4.20 a.m. the Battle for Amiens began. By 7 a.m. it was clear that Monash’s surprises, including deceptive coloured smoke, a massive artillery barrage, and the stealthy, secret movement of 500 tanks, 800 planes and 100,000 Australian soldiers in the initial attack, meant that the Australian Corps was heading for a huge victory.

By early afternoon on 8 August, victory was confirmed.

At 2.05 p.m. Monash made the ‘body-count’ report, telling Rawlinson that casualties were ‘under 600’. There were more than 4000 prisoners with ‘many more coming in’. Soon after, he could reinforce the extent of the rout by cabling his superiors that the 5th Division had captured the LI German Corps HQ at Framerville on the final phase red line.

The 8 p.m. final communiqué to Rawlinson and Haig noted that more than 6000 prisoners had been taken. The haul was 100 guns, including the dangerous heavy and railway type, a train, and ‘hundreds of vehicles and teams of regimental transport’. Then came the less palatable news that ‘total casualties for the whole Corps will not exceed 1200’.21 Given that the number engaged in the assault on day one would have exceeded 100,000, this was an attrition rate of about one per cent. It was a figure that any general could live with, especially in comparison to the hideous carnage resulting from the poor and rushed planning of previous big battles. Monash, naturally ebullient, would sleep well enough on the night of 8 August 1918. His espoused policy of supporting and preserving troops with the coordinated back-up of tanks, air power and artillery had worked in favour of the soldiers.

Overall, the attack had been too successful for Rawlinson and his staff to digest at Fourth Army HQ. Instead of ordering Monash to push his corps due east, the thrust was to be made southeast. The Canadians would take up the cudgel on its front. The Australians would swing their thrust to the right and protect the Canadian left flank along the Amiens–Nesle railway (the southern Australian boundary). Currie’s troops would advance between the railway and the Amiens–Roye road, heading for Lihons. The Australians were supposed to pivot their left on the Somme to Méricourt.

Rawlinson’s ultimate objective for both corps was to take the important railway centre of Roye, east of Lihons. Failing that, it was hoped that the threat to capture it would force the German Army to retreat from the great ‘salient’ or bulge of territory it had eaten into during a big offensive in April and May. At the least, this would stop the Germans using trains from Roye to feed their operations in this salient.

Despite not being fully aware of how brilliant the 8 August attack had been, Monash, by instinct and experience, would have pushed on east to the big bend in the Somme, where the Germans held the towns of Bray, Péronne and Brie. Reports from the front were clear. If he ordered a further drive that continued into the night of the 8th and the next day, the area around that important, almost ninety-degree bend in the river would be overrun by the Australians.

Monash was well aware that the bend territory had been fought over in 1915 and 1916. Then the French and Germans sat tight and belted each other with artillery, converting the area into a wasteland. It was seared with trenches and wire entanglements in the easternmost part on the German front. But between the bend and that devastated area there was another eleven kilometres of unharmed country. Monash wanted to ram home a further advantage across it. But he was restrained, not for the first time in the war. He might have been the thinking commander, who preferred remaining at HQ to wandering around the front line risking his neck in displays of bravado. But when it came to an instinct for forcing victory, he had a more determined streak than any of his peers or superiors.

The orders from Rawlinson stood. Monash had to resist the need to quench his thirst for territorial acquisition. Instead, he wrote new plans and directed Glasgow’s 1st Australian Division to assist the Canadians along the railway.

The success of the Australian advance the day before created a problem. The last two of the 1st Division’s brigades arrived later than expected from the north. When instructed to march on from Amiens railway station to the front, they found it much further than anticipated. The troops arrived late on the morning of 9 August, and missed the move out by the Canadians at 11 a.m.

This logistical problem was covered by the 5th Division ordering its right line brigade – the 15th led by ‘Pompey’ Elliott – which was patrolling the railway itself, to fill the breach before the troops from the 1st Division arrived. Elliott’s men found stiff opposition, but hung on until the foot-weary 1st Division turned up. Then Monash ordered the swing right – southeast – of the 1st and 2nd Divisions. They sliced through the captured Framerville and ended up on 9 August at the foot of Lihons Hill. Resistance had been strong at times but sporadic along a moving front of six kilometres. The Germans had been able to regroup along a ridge at Lihons Hill. They used field and machine guns to attack the Australians, who had to dig in. The tanks were the main targets for the defending Germans. They knocked out many of them.

At night the Australians made contact with the advancing Canadians on the railway.

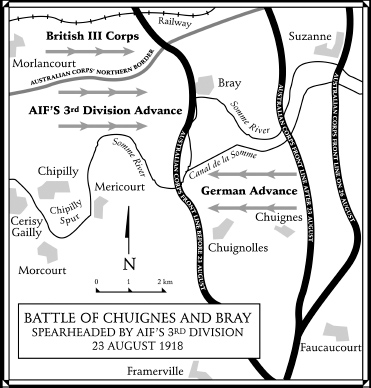

By the end of 9 August, Monash had most concern about his left flank over the river. The night before, as anticipated, the English 58th Division couldn’t budge the Germans on Chipilly Spur. As planned, Sinclair-MacLagan had formed a defensive flank for the Australian 4th Division, yet the Germans had hit several tanks across the river. Artillery duels continued. Monash repeated his requests to Rawlinson to take command of this troublespot. Butler objected, but then suddenly he was removed. The official line was that he was taking prearranged sick leave, which was unlikely at this critical time. General Godley replaced Butler, and to say this pleased Monash is an understatement. For the first time, Monash was in a position of superiority, running the far bigger corps and acting as the spearhead of his own plan.

Monash put an urgent demand that was more like an order to Godley that he (Monash) take over Chipilly Spur. Godley dithered. Under Rawlinson’s orders, he had control of the British sector, not the Commander of the Australian Corps. But Godley, like the entire British High Command, had witnessed Monash’s near-complete annihilation of the enemy the previous day. This gave him an enormous immediate prestige and power. There had been nothing like this success by British forces before. It caused the forceful Godley to hesitate. Monash pressed him. Godley demurred. Monash put his case in more vociferous terms knowing that the ‘elegant’ (as Monash referred to him) Englishman, who lacked ‘technical ability’, would have to capitulate. When he did, Monash was handed ‘limited jurisdiction’ over the north bank of the Somme. Better late than never. He could now tackle that damned spur, which had worried him so much. ‘This was merely getting in the thin end of the wedge …’ Monash wrote. He found himself ‘where I had so strongly desired to be from the first, namely, astride the Somme Valley’.22

The best available brigade was the 13th. Before the major 8 August attack began, it had stayed south of the railway line to deceive the Germans about the arrival of the Canadian Corps. It was now ordered to take Chipilly. But since Monash’s urgent requests, Godley had appraised the situation and decided to take action before the Australians could march there. He had directed the experienced 131st American Regiment to attempt to take it. The Americans began their task at about 4.30 p.m. Two hours later, after heavy fighting, they controlled nearly the entire ridge.

At this time, the 13th Brigade arrived and sent a battalion across the river at Cerisy. ‘They joined the Americans,’ Monash noted with satisfaction, ‘and helped clear up the whole situation. This made my left flank more secure. It enabled MacLagan to withdraw the defensive flank, which he deployed along the river from Cerisy to Morcourt.’ That night of 9 August, Monash took over the 131st American Regiment from the British III Corps and attached it to his 4th Division. Sinclair-MacLagan was put in charge of the newly captured front, which extended several kilometres north of the river to the Crobie–Bray road.

Monash’s organised mind was well satisfied at the end of 9 August with the Australians’ relentless advance. His 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions ran south to north in the line of the new front.

By contrast, General Ludendorff, the joint dictator of Germany with Field Marshal von Hindenburg, was distressed to the point where his staff wondered whether he would have a nervous breakdown. That would come later in the autumn, when he would receive psychiatric counselling. Now he could only attempt to absorb and counter the horrific events of the past forty-eight hours. He wrote in his memoirs: ‘August 8th was the black day of the German Army in the history of the war. This was the worst experience I had to go through …’23

The Prussian-born Ludendorff (who, at fifty-three, was the same age as Monash and George V) had been mainly responsible for Germany’s military policy and strategy from August 1916. He had devised the big 21 March offensive on the Western Front. Ludendorff’s plan was to force a decision favourable to the Germans in secret negotiations between the two sides before the Americans joined the war in Europe. Another million German soldiers at the Western Front had boosted his troop numbers after the 1917 Russian Revolution and Russia’s withdrawal from the war. But he underestimated the resistance of the French in their own homeland and the British forces, especially the Australians and Canadians.

Ludendorff would never have dreamed that a general with a Prussian–German background born at the same time and with roots in a town close to his own birthplace of Kruszewnia, near Poznan, would be his key opponent and nemesis in war. Given Ludendorff’s support for Adolf Hitler in a 1923 coup d’êtat, and the general’s fascist links and paranoia about Jewish conspiracy theories, he would have been driven to his psychiatrist’s couch a lot quicker if he ever learned later that Monash was a Jew.

In his memoirs, writing of the shock of the 8 August attack, Ludendorff described with some feeling how the Australians and Canadians attacked in thick fog ‘that had been rendered still thicker by artificial means’ (Monash’s smoke-screen) with ‘strong squadrons of tanks, but for the rest with no great superiority. The [German] Divisions in line allowed themselves to be overwhelmed.’ To add to the confusion he mentioned how tanks had run through divisional HQ. This might have been a deliberate error on the HQ staff’s behalf. In fact, they had been terrorised by sixteen armoured cars, commanded by one of Monash’s staff officers, Lieutenant Colonel Carter, which would not have sounded so frightening. Ludendorff recalled:

The exhausted [German] Divisions that had been relieved a few days earlier and were lying in the region south-west of Péronne [near the Somme’s big bend] were alarmed and set in motion by the Commander in Chief of the Second Army. At the same time he brought forward towards the breach all available troops. The Rupprecht Army Group dispatched reserves thither by train. The 18th Army threw its own reserves into the battle from the southeast.

The desperate Ludendorff ordered the German Ninth Army, ‘itself in danger’, to help out. Such was the attack’s surprise that it was days before troops could reach the troubled area.

‘It was a very gloomy situation,’ the depressed General noted. ‘Six or seven Divisions that were quite fairly to be described as effective had been completely battered … The situation was uncommonly serious.’ Ludendorff emphasised that if the Australians and the Canadians continued to attack ‘with even comparative vigour’ the Germans would not be able to resist ‘West of the Somme … The wastage of the Second Army had been very great. Heavy toll had also been taken of the reserve which had been thrown in … Owing to the deficit created, our losses had reached such proportions that the [German] Supreme Command [essentially the overworked Ludendorff himself] was faced with the need to disband a series of Divisions, in order to furnish drafts …’

The picture of Germany’s reduced capacity to resist confirmed Monash’s instinct to push east to capitalise on the enormous blow of 8 August. It wasn’t to be. Yet the physical and psychological impact would remain and influence peace negotiations, which were dictated for the Germans by Ludendorff and von Hindenburg.

The ‘deeply confounded’ general saw the writing on the wall for the Germans in the entire conflict when he concluded: ‘8 August made things clear for both [opposing] Army Commands.’24

The Allies now had the upper hand on and off the battlefield.

The Australians had advanced the predicted eight kilometres and taken seven villages, 8000 prisoners, 173 guns and a great deal of extra booty. The Canadians had moved forward nine and a half kilometres, secured twelve villages and taken 5000 prisoners. In all, the British Fourth Army had pushed forward with seven divisions and three in support, against six German front-line divisions. The French on the right had taken a further 3500 prisoners. It was the biggest breakthrough for the Allies in the war so far, and it created a massive bulge in the front line.

Monash pushed his troops on to support the Canadians with diminishing results over the next few days. But the damage was done. Germany had been heaved backwards, and was reeling from a technical knock-out. It would recover and fight on, but now there was no hope of the German Army being other than on the defensive.

Ludendorff was realistic amidst the gloom. ‘We cannot win this war any more,’ he told a colleague, ‘but we must not lose it.’25

Fighting continued through 10 August, intensely in some areas, as the Allies advanced sixteen kilometres east. The smooth running of Monash’s grand plan removed any danger that Amiens, the last bastion before Paris – 120 kilometres south – would be captured. German resistance increased as Ludendorff shored up defences after the irreparable damage of the previous two days.

By 11 August the Allied leaders had fully appreciated Monash’s success and what it could mean for the future. In the early morning, when he was preparing plans for a further advance, Winston Churchill, now British Minister of Munitions, called in to congratulate him and discuss the ‘state of play’. Churchill was interested in Monash’s views about German morale.

At 11 a.m. Haig was driven to Bertangles to ‘formally thank me for the work done’. He brought his Chief of the General Staff, Sir Henry Lawrence. General Sir Julian Byng, the Commander of the British Third Army, arrived while Haig and Lawrence were there. Haig thought it opportune for him to discuss operations with Byng and Lawrence. Monash made as if to leave them in a room near his office, but the others insisted he stay for the entire conference. Monash was pleased that he was ‘frequently asked for my opinions’. He had been so immersed in his command that he hadn’t yet fully comprehended the ramifications of his breakthrough in such a decisive and sweeping victory. The Allied leaders were relieved at last to have a commander with the brilliance and courage to plan victories, particularly without massive carnage of its troops.

Monash’s star was in the ascendant. Everyone wanted to make contact.

At noon, Rawlinson phoned to tell him that Marshal Foch himself was also coming to Bertangles – at 3 p.m. Fresh orders about tactical policy would be given. Monash told Rawlinson that Haig was meeting the five Australian divisional commanders at 2.30 p.m. in Villers-Bretonneux. Rawlinson then changed plans and arranged for Foch to be at an army conference in the fields just west of the village.

In this heady, spontaneous atmosphere of felicitations, Monash realised that his battle planning would be interrupted for the rest of the day when he was informed that Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was also in France and wished to call on him at Bertangles. Wilson, normally someone a general would have to drop everything for, was told that he could find Monash in the village between 2.30 and 3.30 p.m. Wilson would have to join the line of VIP well-wishers.

Monash was driven in the Rolls to a shady spot under trees in a field on the outskirts of the village, which was a hive of activity. Australian and Canadian railway specialists were relaying the track in time for the first train since 7 August to come through from Amiens. A large, wired-in prisoners’ cage was in view across the main road. Small groups of Germans were being herded in to join thousands of inmates.

‘An immense stream of traffic was pouring up the road towards the front,’ Monash noted. ‘Guns, troops, strings of horses and mules, hundreds of motor lorries, ambulance wagons, and the usually motley traffic of war.’26

At 2.30 p.m. Haig met Monash’s divisional commanders – Major Generals Hobbs, Sinclair-MacLagan, Rosenthal, Gellibrand and Glasgow. Haig made a complimentary speech. He became emotional. ‘You do not know what the Australians and Canadians have done for the British Empire in these days,’ he said. Haig tried to go on, but could not. He began to cry. The Australian commanders were embarrassed. They moved away. Yet the moment had its impact. Haig was strong and ruthless. Such a display of his feelings was unprecedented and pertinent.

At this moment Rawlinson arrived with Montgomery. Then Lawrence, Wilson, Currie, Godley and commanders from the cavalry, tanks and Royal Flying Corps turned up.

At 3 p.m. Rawlinson, surrounded by huge maps, began the army conference as planned. He didn’t get very far before more cars appeared carrying Foch, Clemenceau and the French Finance Minister, Klotz. ‘Villers-Bretonneux, only three days before reeking with gas and unapproachable, and now delivered from bondage,’ Monash wrote, ‘was the lodestone which had attracted the individual members of this remarkable assemblage.’27

Rawlinson rolled up his maps. There was no chance of meetings now as the VIPs praised Monash and Currie in heartfelt speeches. The relief in the congratulations was palpable. Uncertainty and hope had been replaced by a true sense now that the enemy would be repulsed thanks to the Australian and Canadian drive.

The deference to Monash exhibited by all the key members of the Allied command surprised him but sank into his psyche. He had stood up to, if not over, the indecisive Rawlinson before the Battles of Hamel and Amiens. Monash would now be even bolder and more inclined to take calculated risks. Like the AIF fighting machine he had built and controlled, he would take some stopping.

Monash’s war planning was again interrupted the next day, 12 August, when he prepared for the arrival of George V at Bertangles. It was an appropriate moment for the King to invest him with a knighthood bestowed months earlier. Monash, aware of his detractors and the political capital that could be made from the occasion, made sure that photographers and film cameramen were there to catch the ceremony.

The King too was keen to make a point by making a public acknowledgement of his own good judgement.

Monash, who had a sense that the King had had some influence in his rise, arranged a guard of honour of 600 men at Bertangles. They lined the driveway under tall chestnut trees. Monash also made sure that an impressive line-up of war trophies was placed in the leafy château’s grounds. The booty included several hundred guns, howitzers, heavy-machine guns, light machine guns, anti-tank guns, field searchlights, transport vehicles, range finders and hundreds of other minor trophies. Monash included ‘a representative selection of a dozen enemy vehicles, both horse-drawn and motor drawn, with teams of horses and harness complete, just as captured’.

Monash organised the 600-strong troop formation. It was made up of 100 men from each of the Australian divisions and another hundred from the Royal Garrison Artillery. They lined both sides of the drive from outside the front gates, with their heraldic figures and coats of arms, to the steps of the piazza in the middle of the château’s 100-metre-long facade.

When the King’s car came into view in brilliant sunshine along a kilometre-long avenue leading up to the château’s gates, Monash called his men to attention. He, Blamey and the Australian Corps chief administrative officer, Brigadier-General Carruthers, greeted the King, who was accompanied only by two aides.

The King took the royal salute from the guard at the gate, inspected it with Monash and then walked with him along the drive. The King inspected the troops, stopping for small talk with several of the men. They then walked up the steps from the piazza to the reception room. Inside, Monash presented the King to the château’s owner, the Marquis de Clermont-Tonnerre, ‘a very old man with a long white beard’.

Monash then introduced his five divisional commanders with whom the King chatted. After ten minutes, they moved down to the piazza for the investiture. A sword, a small table and a footstool were arranged on a carpet on steps. With about a hundred of Monash’s staff looking on, his name was called. He stepped up and stood to attention in front of the King.

‘Kneel, please,’ the King said.

Monash went down on his right knee.

The King then began to knight him by tapping him on the right shoulder. Monash began to rise before the King had swung the sword on to his left shoulder, but stayed down when he saw the King’s movement. The investiture ended with the King saying: ‘Arise, Sir John.’

He handed Monash the insignia of a Knight Commander of the Bath.

The King smiled, pumped his hand and made a little speech ‘commending my work and that of the Australian troops’.28

Onlookers applauded. The King then walked with Monash around the château’s grounds inspecting the battle trophies.

The whole ceremony had been going just thirty minutes before the King’s car pulled up at the steps and he left. Monash called for three cheers from the troops lining the drive. They didn’t respond with much voice, especially those at the other end of the drive. Monash tried again, but the dispersed guard responded sporadically as before. It was a minor hiccup in an otherwise glittering occasion, captured for posterity on film.

Monash entry in his small diary for 12 August 1918, which he would list later as one of the three or four greatest days of his life, reflected its hectic mix of war and ceremony:

Indoors forenoon.

10 brigade captures Proyant.

Prepare for King’s visit being made in front of château.

About 50 field guns, many trench mortars, machine-guns and other trophies.

Attend Army conference at Villers-Bretonneux.

12.30 Divisional Commanders attend.

Return to Corps 2.25 p.m.

The King due 2.30 arrives at about 3.00 p.m. Inspects guard walks to château steps. Am decorated with Star and Order of KCB. O’Keefe DMS Army KCMG. Later watches Boche transport and field ambulance being driven past and then departs.

Successful attack by 13 bge N of Somme. Capture 183 prisoners.29

The King noted in his diary on the same day:

Proceeding to Bertangles was received [by] General Monash, GOC Australian Corps & his Generals & representatives from all the Australian divisions who are now fighting in this battle. I gave General Monash & General O’Keeff [sic] the KCB & knighted them. They showed me some of the many Guns and machine-guns & horses & carts & ambulances which they have just captured from the Germans, they got over 300 horses …30

After the tap on each shoulder, when he arose as KCB, Monash had received his battlefield honours. But there was still no thought about striding off to become a desk-bound, paper-shuffling general. The war had not yet been won. He was right in the middle of further attack plans. The well-wishers, and even the King’s visit, would have been a distraction, no matter how much the visits were appreciated. Nobody was thinking that the war would not go into 1919. But Monash and other commanders were keen to drive home their advantage, now.

Murdoch kept pushing Hughes about the position of AIF GOC – General Officer Commanding, but was having no effect. The PM had seen the preparations for Hamel and had been impressed by Monash and his command. As a VIP visitor he experienced the usual deference from those he met and who recognised him as the King’s first minister in Australia. Yet Hughes had also witnessed the reaction of the soldiers and officers to their commander. Two hundred thousand men and thousands of killing machines under the control of one man on a battlefield, with everyone formally acknowledging his power by speech, action and body language, was something else. It was tangible, raw potency. And if politicians understood one thing, it was power.

Hughes first received the news about Amiens from Munro Ferguson, who had cabled him on 8 August: ‘Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash wishes me to convey to you on behalf of the Australian Corps that the Australian Flag was hoisted over Harbonnières today at noon.’ These words would stay with Hughes for life. There was no chance of his now relieving Monash against his will. For the moment, he had become his favourite soldier. There were votes in battle wins like Hamel and Amiens. The PM saw the press reaction.

Murdoch and Bean were now left impotent. The best they could hope for was that Monash would sooner or later want the GOC. Murdoch had lost patience with White and indulged in a little less self-delusion when he wrote to Bean: ‘I doubt very much if he [Hughes] will give White the Corps. That will follow ultimately, if White stops fooling about. He is every day proving himself to be less sound in his judgment than he should be.’31 In fact, White had been serious and consistent. He remained in support of Monash.

Bean, in contrast to Murdoch, now developed doubts about his own judgement. He continued to intrigue with Murdoch but with far less fervour. Thirty-eight years later, he would write about the Bean–Murdoch ‘high-intentioned but ill-judged intervention. That it resulted in no harm whatever was probably due to the magnanimity of both White and Monash.’32

After Amiens, Hughes could see the need for a strong politician, who had everyone’s respect in London, as GOC. The war was reaching a critical stage, and he wanted to be in a position to make sure he could get his way. If the number of Australian casualties became unacceptable to the electorate, Hughes would be desperate to start pulling out the AIF. It was one thing to order it, and another to have it carried through in communication and directives from the British High Command in London to the Western Front. Hughes now told his cabinet that Birdwood should be replaced as GOC, but not by Monash, unless he wanted it, and everyone knew he would not. Hughes was saying Monash could have his choice. If he wished to stay Corps Commander, he could.

It seemed that Pearce would have to move to London to take up the GOC job. Out of courtesy to the much-respected Birdwood, Hughes on 12 August offered him the GOC position full time, which meant he would have to stop running the British Fifth Army. No one expected him to accept, but he did. Birdwood enjoyed Dominion troops and officers more than his own British soldiers. He sensed, too, that the AIF was going to continue at the forefront of the conflict. It would be more exciting, even rewarding. Some thought the offer a slight to Monash, but he could not be a politician and command the corps, especially in the current heated battles. Besides, Birdwood would not take up the full-time job until 30 November. The war was too preoccupying for such an important change at the moment.

Murdoch tried to stir the issue in an article in the Melbourne Herald that made the future juggling seem like a down-grade for Monash. But it had little impact. Too many eyes were now on the military struggle to worry about the shuffling of administrative chairs a long way from the front.