8

The Price of a Vote: From Local Elections to General Microtargeting

THROUGHOUT THE PREVIOUS CHAPTERS, we have surveyed the rules governing election campaigns in Western Europe and North America, paying special attention to the limits (or absence of limits) on campaign funding and candidates’ expenses. In France since the late 1980s, unlike in the United States today, election expenses have been subject to major legal restrictions; not only are candidates unable to do what they like with their money—they cannot, for example, buy themselves a series of TV ads—but they are also prohibited from spending more than a certain amount fixed by law. In the 2017 presidential campaign, candidates who ran in the first round could not spend more than 16.851 million euros, and those who made it to the second round were limited to 22.509 million euros. In the legislative elections, the rules on campaign spending are a little more complex, since they involve a fixed limit of 38,000 euros per candidate plus 0.15 euros per resident of the constituency.1 Thus, whereas a candidate in the second constituency of the Hautes-Alpes department (centered on the city of Briançon) could spend no more than 47,930 euros in 2017, the total rose to 61,300 euros for a candidate in the fifth constituency of Loire-Atlantique.2 There are similar tight restrictions on spending in local elections: the limit for municipal elections, for example (in all constituencies with more than 9,000 residents3), ranges from 1.22 euros per resident for the first 15,000, 1.07 euros for 15,001 to 30,000 residents, and so on. (I will spare you other superfluous details, but I wish you the best of luck if you plan on winning a city hall and want to work out how much you are permitted to spend.4) In 2014, a candidate in the municipal elections at Bourg-en-Bresse (Ain department) could not spend more than 53,312 euros; that may not sound like much, but it was a lot more than the ceiling in neighboring communes (15,676 euros in Gex, for example).5 And remember that in France the permissible amount that anyone may donate to a candidate is very low (4,600 euros per campaign) and that since 1995 no direct corporate donations have been allowed.

So, a few tens of thousands of euros for an election—sometimes even less. That must sound ludicrous to readers who recall the hundreds of millions of dollars available in American campaigns. But does it mean that money plays no role in election results in France, that campaign spending has only a marginal influence on whether a candidate will be elected? Does it similarly imply that we should not care about campaign spending in the United Kingdom, where the spending limits faced by the candidates are even lower?

I will begin by showing you that, even in France and the United Kingdom, election spending has a real impact on the votes obtained by candidates. Then we shall try to understand why. After examining what candidates do with their money in France, the United Kingdom, or the United States—from traditional campaign meetings to the microtargeting of electors on social media—we shall see that, contrary to a widespread idea, new technologies have neither made it easier for new candidates to emerge nor led to a lowering of campaign costs. Online campaigning is an expensive business, and it can pay big dividends. Since 2004, in the United States, the victorious presidential candidate has always been the one who spends most of his or her electoral resources online; the difference between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton is striking in this respect. We shall then bring Part Two to an end, and the time will come for us to turn to solutions. Based on the aberrations and innovations reviewed in the past eight chapters, these will offer the possibility of recovering an idea of democracy as “one person, one vote.”

How Campaign Spending Influences Voting Behavior

I studied the influence of campaign spending on election results in a research and data collection project conducted with Yasmine Bekkouche on France and Edgard Dewitte on the United Kingdom.6 We looked at the role of money in the political process during the past decades—a focus that was particularly important for several reasons. First, economic and political research on these questions continues to suffer from a strong US bias, with the result that, although there is no lack of factual material about the growing and disturbing weight of money in US elections, very little is known about the effects of election spending elsewhere in the world.7 And second, France and the United Kingdom are interesting from this point of view precisely because the tight limits on campaign spending might lead one to suppose that it does not have a major influence on voting behavior. America is America, so no danger in Europe? It was necessary to investigate whether this was true.

On the basis of the National Commission on Campaign Accounts and Political Funding (CNCCFP) archives and electoral data, Yasmine Bekkouche and I began by constructing a new database of all funding associated with legislative and municipal elections in France since the early 1990s.8 More specifically, our data cover four municipal elections (1995, 2001, 2008, and 2014) and five legislative elections (1993, 1997, 2002, 2007, and 2012), as well as the campaign spending and election results of approximately 40,000 candidates. The new database I constructed with Edgard Dewitte covers all the UK general elections since 1857, including detailed expenses for 34,000 candidates. In both cases, the results are astonishing.

Very Uneven Resources among Election Candidates

The first striking feature is that both the amount of campaign spending and the origin of campaign funds vary widely among candidates, mainly—but not only—according to their political party.9 As highlighted in Chapter 3, in practically all the democracies of Western Europe, parties on the right received much more each year in individual and corporate donations than parties on the left. This inequality is also found at the level of election campaigns. Figure 57 shows the average size of donations received by candidates of the different parties in the French legislative elections. On average, candidates on the right receive 18,000 euros in private donations—that is, more than the average total expenses of an election candidate (a little under 15,000 euros). By comparison, Socialist Party candidates receive less than 10,000 euros, Communist Party candidates 2,300 euros, and those from other parties less than 500 euros.

Figure 57. Average donation received by candidates in legislative elections, by political party, France, 1993–2015

It might be thought that municipal elections—where many candidates run as “independents,” and votes often depend more on local factors than on the national political context—would be characterized by greater “equality” in the donations received by candidates. However, this is not what we see in the data. As in legislative elections, candidates on the right are the best endowed with resources; they receive on average 3,400 euros more in private donations than candidates on the left, while those on the far right and the far left receive hardly any donations at all. What are the consequences? Being better funded, conservative candidates spend more than their opponents. The extra private money might have been reflected in a smaller contribution by their parties to campaign expenses, but again this is not the case—for one simple reason. The parties of the Right are themselves richer and can do more to help their candidates. Besides, since election spending is usually a highly effective instrument for winning votes, why should candidates deny themselves any opportunity to increase their chances of success?

In the end, the 3,400 euros of extra donations that right-wing candidates receive for municipal elections in France are immediately translated into additional revenues, so that the candidates have on average 4,200 euros more than their left-wing opponents and are therefore able to spend more. Similarly, in the case of legislative elections, the total revenues for a right-wing candidate average 53,000 euros, which is 12,200 euros more than for a Socialist Party candidate. Some might be tempted to say that the difference is only a few thousand euros, but those few thousand are almost as much as the average expenses of a candidate in the elections.

Interestingly, the only item in the revenues that is lower for a right-wing than for a left-wing candidate is the personal contribution. In fact, what is called “personal contribution” corresponds to the part of campaign expenses that a candidate can have reimbursed, so long as he or she has received enough votes (at least 5 percent of the total) in the first round. In other words, the candidates of the Left as well as challengers from smaller parties take more of a personal financial risk than their counterparts on the right when they run in elections, and in many cases they have recourse to loans. (This comes as a surprise when we think how highly parties of the Right tend to value individual risk-taking.10) Moreover, since candidates cannot claim a refund for more than 47.5 percent of expenses, it is very rare that their personal spending rises above that ceiling. Not everyone is Donald Trump, ready to pay out of his own pocket to ensure an election victory. Nor, of course, does everyone have companies he can harness in defiance of any notion of a conflict of interests.

On average, then, right-wing candidates in both municipal and legislative elections receive more than their opponents by way of private donations, and they spend more per elector on their campaigns. The main consequence of this is an extra boost to their total vote.

Election Results Partly Determined by Campaign Expenses

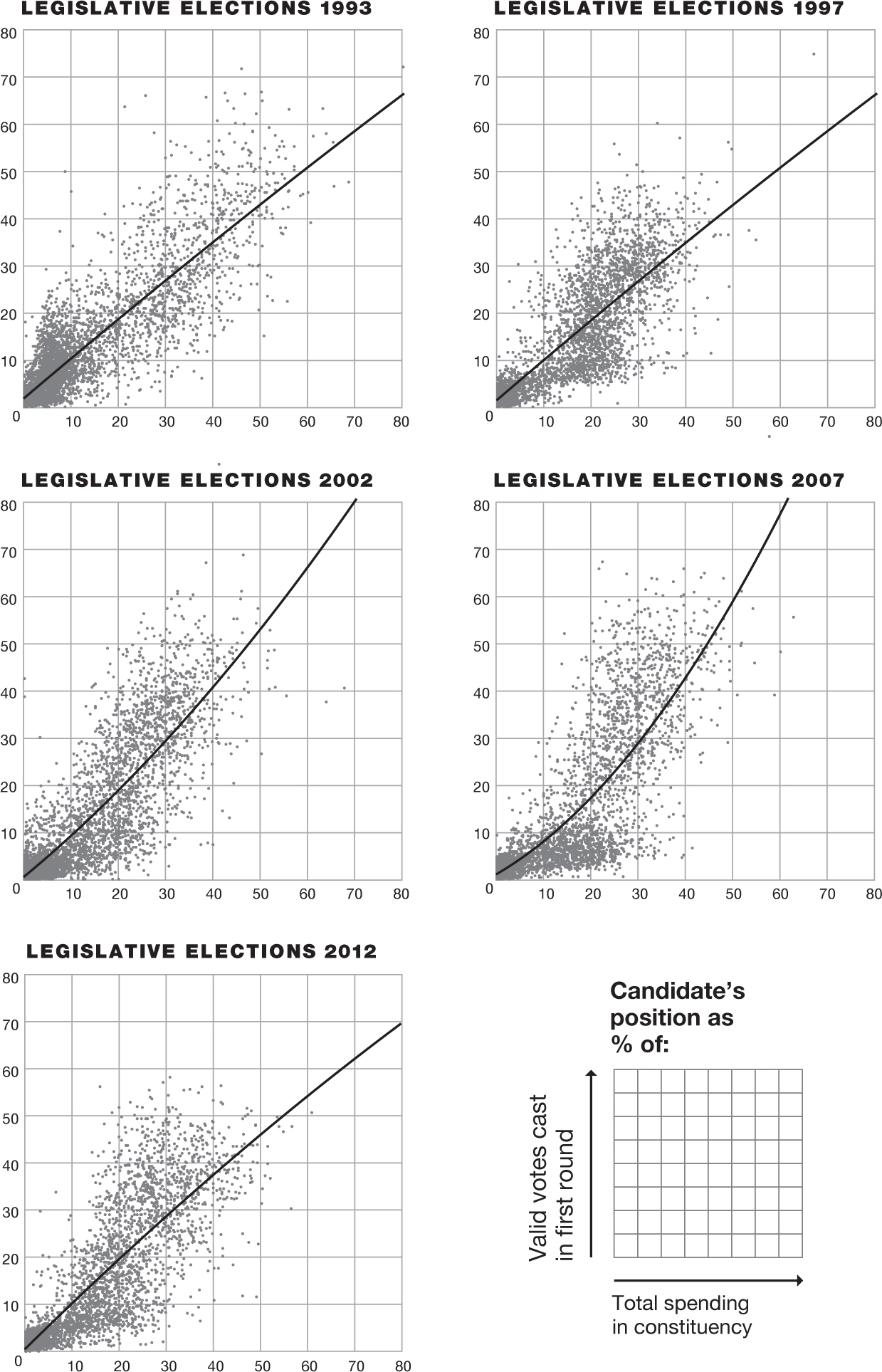

The main result of the research projects I conducted on France with Yasmine Bekkouche and on the United Kingdom with Edgard Dewitte is as follows. Campaign spending on such things as communications, public meetings, leaflets, or door-to-door canvassing has a direct impact on the number of votes candidates obtain in both municipal and legislative elections. This emerges very clearly from Figure 58, Figure 59, and Figure 60a–d, which demonstrate that, for legislative and municipal elections in France as well as for general elections in the United Kingdom, there is a strong correlation between a candidate’s percentage of the first-round vote and her percentage of total election spending in the electoral district (each point on these charts stands for a candidate). In general, the greater the amount by which one candidate’s spending exceeds that of other candidates, the higher is her share of the first-round vote.11 This fit is strikingly similar across the years (it holds for the first half of the twentieth century as well as for the twenty-first century) and across countries (notwithstanding the fact that the United Kingdom and France have different electoral systems).

Of course, correlation is not the same as causality, and many factors may be involved other than a direct causal effect of spending on votes. For example, a more promising candidate might obtain more donations (money goes to money, and therefore to winners) as well as more votes because she is popular, not because her spending has brought in more votes.12 Well aware of this problem, we proceeded in the following way to identify the causal effect of spending. First of all, we isolated the effect of a variation in spending on the number of votes received by a candidate by introducing an “other things being equal” clause: that is to say, we checked a systematic preference for the Left or the Right in voting behavior, as well as the popularity of the different parties in the election year under consideration, against the social-demographic specificities of each electoral district (occupational categories, educational levels, age groups, and so on).13

We concentrated mainly on the impact of “exogenous” variations on the revenues of candidates: that is, variations determined by factors external to the district or candidate in question, such as the 1995 French legislation that prohibited corporate donations to election campaigns. That sudden and unexpected reform led to a huge fall in the resources available to some candidates but not others, even in geographical areas with the same characteristics and for candidates in the same political party. It is therefore a near-perfect natural experiment, and the results speak volumes.

Figure 58. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, legislative elections, France, 1993–2012

Figure 59. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, municipal elections, France, 1995–2014

Figure 60a. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, general elections, United Kingdom, 1885–1955

Figure 60b. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, general elections, United Kingdom, 1959–1975

Figure 60c. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, general elections, United Kingdom, 1979–2001

Figure 60d. Correlation between campaign expenses and voting score, general elections, United Kingdom, 2005–2017

According to our estimates, the price of a vote in France is roughly six euros for legislative elections and thirty-two euros for municipal elections. This implies that the average of 8,000 extra euros in private donations received by candidates of the Right gives them an advantage of 1,367 to 2,734 votes over candidates of the Left in legislative elections (depending on whether the gain is at the expense of the Socialist Party or another party). That works out at 3 to 6 percent of the votes cast in the first round of the elections. In other words, if there were no cap on spending, private money could easily alter election results. A few euros, one vote. And don’t forget that the state (that is, the taxpayer) picks up some of the bill, since two-thirds of the value of a rich person’s donation comes out of the public purse.

This effect is all the more problematic because the extra spending is done mostly on the right of the political spectrum; the implications would be different if it were at random that Socialist, Republican, Communist, and other candidates received and spent more than their rivals. But what we see is that the perennial Conservative legislator Patrick Balkany—and not his Socialist rival Gilles Catoire—received more than 1.7 million francs (353,000 euros) in 1993 for his election in the fifth district of the Hauts-de-Seine department, 98 percent of it from private companies, at a time when the ceiling on expenditure was 500,000 francs!14 And we know that there is perhaps more to this than meets the eye. Another well-known figure is Alain Juppé, who served as mayor of Bordeaux from 1995 to 2004 (incidentally, also being French prime minister for two years, starting in May 1995). He received more than 1 million francs (222,000 euros) in donations, of which more than two-thirds came from just seven companies; his Socialist rival, Gilles Savary, received less than 80,000 francs from companies, and the other six candidates nothing at all.

The Strange Defeat Explained?

Perhaps there is justice in this world, however. The new legislation banning corporate donations in 1995 was applied for the first time in the national elections of 1997. Patrick Balkany, who may have sensed a change in the wind—and had anyway been disqualified from standing for two years—gallantly gave up his place to his wife Isabelle.15 But the poor lady had probably not expected the corporate manna to dry up, and she ran for election with a mere 148,000 francs in donations, more than ten times less than her spouse had received four years earlier. In the end, with scarcely more resources than her two main rivals, Olivier de Chazeaux and Catherine Lalumière, she did not even make it through to the second round.

Beyond the case of the Balkanys, the effect of election spending on voting behavior is such that it may largely explain the “strange defeat” of the Right in the legislative elections of 1997, just four years after the Socialist Party debacle in 1993, and two years after Jacques Chirac’s clear victory in the presidential election of 1995. The ban on corporate donations affected only candidates who had received corporate donations in the past—mostly on the right, and only some of them. Whereas the average size of corporate donations received by a candidate in 1993 had been 8,600 euros (representing approximately a quarter of the total of private donations), the median donation had been zero. In other words, more than a half of candidates had received no corporate donation in 1993—and were therefore unaffected by the reform—but candidates on the right had received an average of 40,000 euros from that source!

Like the Balkany couple, these candidates were generally incapable of recovering from the ban introduced in 1995. On average, one extra euro in corporate donations received in 1993 is associated with a 0.46 euro fall in the total revenues of that candidate between 1993 and 1997. In other words, the data tell us that the total revenues in 1997 of a candidate who had received corporate donations worth 100,000 francs in 1993 averaged only 54,000 francs. Such a drop may be explained by the fact that the 1997 elections took everyone unawares; no election had been expected before 1998, until Jacques Chirac surprised even people in his own party by announcing the dissolution of the National Assembly in April 1997 and the holding of elections in May. In making this decision, he felt sure of winning the legislative elections. But he was mistaken. Our results allow us to see that at least part of the reason for this was that candidates of the Right, used to raising money from private companies, did not have enough time to find new donors. They therefore obtained a lower score than they would have done in the absence of the ban, since the new state of their finances meant that they could not spend as much as they had anticipated during their election campaigns.

The nature of our estimates is such that they remain imprecise—we cannot replay the elections in a laboratory—but it would seem from the data available to us that the total impact of the funding reform may have swung several dozen constituencies from the Right to the Left, by a sufficient amount to determine the overall election result. For we should remember that the Socialist Party won by a very small margin, with 255 seats (plus thirty-five for the Communists and seven for the Ecologists) against 251 seats for the ruling Rassemblement pour la République (RPR)–Union pour la Démocratie Française (UDF) coalition.

Thus, despite the existing ceilings on election expenses and the limits on private donations, money plays an important role in European politics, sometimes even a decisive one for the result of elections. Despite or because. Whereas the existing literature obtains conflicting results regarding the impact of campaign expenditures on votes, this may be due to the fact that this literature has centered mostly on the United States, where campaign spending is not capped. Hence, given that candidates’ expenditures keep growing in US elections, the diminishing returns of spending may dominate—what is the value of one additional dollar in television advertising when you have already spent over a million? On the other hand, in countries such as France and the United Kingdom, where spending is limited, the marginal returns of campaign spending are actually positive. Obviously, this does not mean that money matters less in places with no regulation. The absence of campaign finance limitations adversely affects electoral competition; in the United States, as of today, candidates by and large need to be wealthy to run. This means that, even in countries such as France and the United Kingdom, the role of money in politics has to be further reduced. To lessen this role in the future and to make our democracies more representative, there would have to be tighter limits on private money and a more equitable system of public funding. These will be the themes of Part Three.

Statistical Regularities and Freak Accidents

I would stress that, although a few additional tens of thousands of euros—or mere thousands in small constituencies—may be enough on average to swing an election, it will always be possible to find counterexamples. So, when I say that the price of a vote is thirty-two euros in French municipal elections, I am talking only of a statistical regularity—an average that by no means implies that high spending is always a guarantee of victory. The Koch brothers learned this to their detriment in the presidential election of 1980: David Koch could run for the vice presidency alongside Ed Clark on the Libertarian Party ticket and immediately spend more than $2 million, but this was not enough for the party to win more than 1 percent of the vote.16 However, the Koch brothers learned some lessons from the experience. Since then, they have decided to go about things differently, creating and pouring millions into numerous think tanks (as we saw in Chapter 4). Money counts in politics, but only if you put it on the right horse.

I could mention any number of other “statistical irregularities,” including such examples in France as that of Benoît Hamon in the 2017 presidential election (who was well funded but attracted few votes) or Nicolas Sarkozy in 2012. But I am sure you can think of some yourself. We can see the importance of systematically analyzing data, to raise the debate to a general level rather than the back-and-forth exchange of anecdotes, examples, and counterexamples that allows anyone to come up with arguments against the regulation of campaign expenses. Systematic data have now been collected and used in the case of French and British elections, district by district, and the results are clear.

Lastly, let us note that this statistical regularity—which I established together with Yasmine Bekkouche and Edgard Dewitte—rests solely on data relating to official funding and registered as such. But I am by no means unaware that not only in France or the United States, but also in India or Brazil, there is a lot of what Jane Mayer calls “dark money”: that is, campaign influxes—and outflows—that by definition do not appear in my data. Nor am I unaware that election accounts often lack transparency—the commissions in charge of analyzing them (the CNCCFP in France and the Electoral Commission in the United Kingdom) regularly reject a certain number—and that the resources of these commissions, which have been sharply reduced in recent years in France, need to be given a considerable boost. The significant effect of election spending on voting behavior that we were able to identify underestimates the scale of what happens in reality, but it still testifies to the important role of money in the electoral process.

Thus, it would be rather naïve to suggest that French political parties and election campaigns benefited from corporate donations only between 1988 and 1995. We know that, before the law of 1988 came into effect, there had been numerous transfers, including unauthorized ones, between companies and parties,17 and that corporate kickbacks to political parties in return for the award of public contracts were never an Italian peculiarity (which is, indeed, why regulation was finally introduced in France). Such practices have been amply documented in André Campana’s excellent book, L’Argent secret, as well as in the works of Éric Phélippeau, who draws a picture, based on Sciences Po press kits, of the hidden funds paid by corporations to political parties in 1993.18 Similarly, it would be naïve to think that, since companies no longer have the right to fund parties and campaigns, they have actually stopped doing it. We do not need to delve into relations with Libya, but simply bear in mind all the simple (and illegal) devices still open to corporations—from good old bribes to violations of the spirit of the law, such as encouraging employees to donate with a company credit card and to pocket the associated tax relief in exchange for the service rendered. Besides, hidden campaign funding includes not only corporate gifts but also individual donations. I am thinking, at random, of Nicolas Sarkozy’s visits to the L’Oréal heiress, Liliane Bettencourt.

Despite all the visits and bribes, despite the millions of euros that neither shrewd researchers nor supervisory authorities are able to track down, the official data alone reveal that money has a significant impact on election results. On average, higher spending for a candidate means that he or she obtains a better result. How is this to be explained?

The Role of Money in Politics—From Campaign Meetings to Social Media

I can see you raise your eyebrows. If, without being an activist or member, you have always voted (at least in national elections) for a political party, your political party, you may find it difficult to make a link between what candidates of that or other parties spend and how you vote. After all, your vote is a matter of course. Would a few euros be enough to swing it? Surely not—the very idea seems to jar. Yet, before each polling day, many voters have not yet decided whether they will vote at all or for which candidate they will cast their ballot. It is on these undecided citizens that election campaigns concentrate their efforts and their spending, since there is some hope of swinging their votes. In which ways? There is no lack of possibilities, and candidates often show proof of originality.

Advertising Culture

The nature of campaign spending varies enormously from country to country, depending first of all on what candidates are permitted to spend. In the United States, one of the main objects of spending is TV advertising, which may take either of two forms: “positive” publicity, to “sell” candidates and their programs, or—more surprisingly—“negative” publicity directed against their rivals.19 For example, instead of vaunting the merits of Hillary Clinton’s program on climate change (such as her Clean Energy Challenge worth $60 million), her “negative” campaign publicity attacked the indecency of Donald Trump and his reckless judgments. And on the other side, Trump’s TV advertising frequently focused on Hillary Clinton and her alleged corrupt practices.20

Everything—or rather, anything—can be said: that is the best way of summing up US election campaigns; anything can be said, so long as you have the means to buy airtime, and enough voters’ brains are available. And since this is America, all is in the name of free speech. It may be amusing to recall that, at least with regard to television, things might have worked out differently. For in the United States as in France, election campaigns are regulated by an “equal time rule.” The famous Section 315 of the Communications Act requires TV and radio stations to treat all candidates equally.21 This could have meant that they were required to “offer” the same speaking time free of charge to each candidate, but it actually gave rise to a completely different interpretation: if a channel sells airtime at a certain price to one candidate, it must agree to sell the same airtime to other candidates at the same price.22 Boom! The signal was given for election spending to take off. Too bad for anyone who could not afford to buy a quarter of an hour of celebrity. That is how America defines free speech and equality.

Donald Trump’s spending on TV and other publicity in 2016 came to more than $198 million, or 55 percent of his total spending, while Hillary Clinton’s amounted to $352 million, or 58 percent of her total spending.23 This massive recourse to radio and television as campaign tools is far from unique to the United States. In Canada, for instance, if we take spending in the past four parliamentary elections (2004, 2008, 2011, and 2015), we see that on average the parties allocated 39 percent of their campaign spending to audiovisual advertising (Figure 61).24 There are notable differences among the parties, however, the two main ones, the Conservative and the Liberal Party, generally having greater recourse to TV and radio to try to win over voters. In 2015, the Liberal Party spent 18.9 million euros on TV and radio advertising during its successful campaign.

In France (as well as Belgium and the United Kingdom), regardless of any cap on spending by candidates and parties, the kind of sums seen in North America could not be deployed in election campaigns, since electoral advertising is not permitted on radio or television. That saves millions of euros from the beginning. But this does not mean that candidates do not have recourse to publicity in these Western European countries, only that they have to “content themselves” with other media supports. For a long time, the only other option was “printed propaganda,” but now there are also “telephone campaigns” and—a new form that may eventually prove the most effective—online publicity. In 2016, Donald Trump devoted $85.7 million to online advertising, and Hillary Clinton approximately $32 million. What are we talking about exactly?

Figure 61. Percentage of campaign spending devoted to TV and radio advertising, by political party, legislative elections, Canada, averages 2004–2015

On the one hand, there is the kind of straightforward publicity on the internet and social media that you can see every day of the week, except that it is political rather than commercial. On the other hand—and this is one of the real novelties of recent years—there is the sponsoring of tweets and Facebook posts (which appears in the “post boost” or “post promotion” categories of candidates’ spending). Finally, and although candidates tend to be more discreet about this, there are the “fake followers” bought on Twitter and on Facebook or Instagram. Of course, these are very hard to quantify precisely, especially as digital robots (the famous “bots”) have now joined fake human followers, that is, real individuals, often located in India or Pakistan, whose job it is to “like” their clients’ posts; it seems to have been established that both Trump and Clinton had a significant number of robots among their millions of followers on Twitter25—as did Obama before them. Nor is this phenomenon confined to the United States; French politicians also evidently make use of fake Twitter subscribers. Countless companies specialize in selling “friends” and other followers on social media; I advise readers in need of digital affection to try searching online for “How to Become Twitter Famous.” But it will be at their own peril, since companies that specialize in detecting fake subscribers are also legion.

This recourse to a variety of fake subscribers obviously creates manifold problems, yet it remains a legal gray area in most democracies. In my view, it has become an urgent matter to regulate such practices. On the one hand, they should be clearly recognized for what they are: an attempt to manipulate the electoral process. There is very little difference between the use of “fake followers” to boost public perceptions of a candidate’s popularity and the publication of rigged opinion polls, for example. In France, election surveys are regulated by law and placed under the supervision of a special Survey Commission.26 Why should fake friends on social media—the new barometers of public opinion—not be subject to the same regulation? On the other hand, the recourse to fake subscribers poses problems of privacy. For how are these fake followers constructed? The chief way is through information taken (one might say stolen) from the profiles of real followers, who are not asked for their real opinions. So, @reader—you whose eyes are now open to what is going on—have you already come across your digital twin @Reader, who uses not only your name, with a slight alteration, but often also your profile picture?

Facebook and Big Data

Nowadays, social media are used not only as a publicity support or mirror for boosting the popularity of candidates for public office, but also as a campaign instrument, an informational tool, for teams seeking to conquer new voters.27 In Chapter 4, I briefly noted the possible role that the American billionaires Robert and Rebekah Mercer played in the Brexit referendum victory in the United Kingdom, through the precise targeting of voters on Facebook. But such practices are increasingly common and occupy a growing place in the spending of candidates for public office (or anyway, of those who have the money to spend). Many campaigns use information posted on social media to try to “hack” the electorate, as Eitan Hersh shows in his excellent book.28

Media coverage of the Cambridge Analytica affair in the spring of 2018 finally sparked off public debate on the ways in which political campaigns misappropriate information about citizens that ought to be purely private. After the Brexit referendum, it came to light that data stolen by Cambridge Analytica had been used during the Donald Trump campaign to target American voters. Whether or not this helped to swing the election in Trump’s favor is not the issue; rather it is the urgent need for regulations to ensure that such attempts at manipulation do not recur in the future.

Of course, hundreds of millions of euros would not be enough to get all French (let alone American) citizens to open their doors to canvassers, and it is not a new idea that party campaigners may use precise data about the electorate to fine-tune their efforts. Eitan Hersh traces such use of electoral registers back to the late nineteenth century. But what has changed with the digital revolution are the scale and the resourcing of this practice. Citizens may rightly be frightened at the quantity of information circulating about them on which campaigns can potentially draw, especially as much of it, though supposedly private, is described as “commercial.”29

Thus, in the United States today, Democratic Party campaigns rely on the constantly updated Catalist database, which contains hundreds of items of information about each voter at the national level.30 All in all, since the creation of Catalist in 2006 (as a for-profit business, we should note), election candidates or their electoral committees have spent nearly 4.1 million euros to have access to these data.31 To this should be added all the campaign spending whose main beneficiary has been NGP VAN, the user interface that the Democrats employ to contact their electors: 67 million euros since 2013, an average of 4.1 million euros a year between 2007 and 2017.32 We are looking at an immense financial effort to take the greatest advantage of new voter-targeting technology.

Not to be outdone, the Republicans have access to the Voter Vault database, which, together with its user interface, is operated by the party internally. This is an important difference, which means that while the Democrats use an independent for-profit company, the Republicans for a long time relied only on their own resources. I say “for a long time” because most Republican candidates now use the i360 company, whose database, developed by the billionaire Koch brothers, contains a detailed portrait of 250 million American consumers and more than 190 million registered voters.33 Koch brothers: 1, Republican National Committee: 0. Didn’t I say that too much reliance on a few billionaires can lead you seriously astray? Since 2011, more than 4 million euros have been spent on this company, including nearly 2.6 million in 2016 alone.

Dangers of Microtargeting

Let us pause for a moment to consider a simple, but often overlooked, normative question: Is it a good thing that political movements of any kind can possess large quantities of data from electoral registers? On the “yes” side, it might be said that, if this information helps politicians to be more in touch with their voters’ preferences, it will serve the people’s needs, and that, at a time when we rightly lament the widespread disconnect from politics, anything likely to increase voter turnout can only be good. On the “no” side, the first point to make—remember the work of Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page reviewed in Chapter 7—is that politicians today tend to respond less than in the past to the preferences of the majority. Data are for winning elections; preferences are about humoring those who fund the acquisition of data.

Imagine a world in which politicians can perfectly microtarget voters. What does that imply? Quite simply, those politicians will in the end heed the preferences only of those who help them swing the vote. It’s a little like with rich donors: if money is all that counts for an election, and if a handful of billionaires can contribute more to my campaign financially than millions of voters, then I may as well target all my campaign efforts—and all the policies I implement—toward that handful of megarich supporters who can ensure I am elected. It is the argument from effectiveness—which, of course, turns against the argument from democracy.

In his book, Eitan Hersh develops a further argument that should weigh on the “no” side of the scales. Campaigns use mainly public data to target voters—or rather, data made public following a legislative decision, and within the United States itself what is public or not varies widely from state to state. Consequently, there is a real conflict between the administrative interests of politicians (one of whose tasks is to protect the private lives of citizens) and their political interests (which push them to make as much information as possible publicly available, so that they can themselves use it in their campaigns). It is important that citizens be aware of this, because politicians are not going to tie their own hands all by themselves.

The End of Intermediaries?

The growing weight of electoral spending on social media also testifies to the growing importance of a direct relationship between politicians or legislators and ordinary citizens. It is as if institutional mediation in the shape of political parties, as well as mass media and labor unions, has lost the trust of citizens and is no longer necessary—or worse, is actually pernicious. Some of the most popular parties today, beginning with the Five Stars Movement in Italy, define themselves as anti-parties; they feature a rejection of the old vertical structures of existing parties and a strong desire for horizontality (surprisingly allied, it must be said, with a certain leader cult).

This is not the place to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of horizontality; we shall consider the question of participatory democracy at length in the next chapter. But we do need to stress one important point. Some would have us believe that, in this new world beyond intermediation, money plays no more than a marginal role in politics; that the age of big spending, high-maintenance parties, campaign headquarters, and expensive rallies is gone forever; and that there is therefore no longer any need for a cap on campaign spending. But that is a wrong conclusion. Publicity on social media, online videos, YouTube channels, voter targeting, the recruitment of one or more “community managers”: all this comes at a price, and the price is high. Ask Jean-Luc Mélenchon how much his holograms cost him!

I have calculated, for the last four US presidential elections, the percentage of each candidate’s campaign spending that was spent online—on items ranging from the creation of a website through voter targeting on social media to the sponsoring of Facebook posts and other kinds of e-publicity. Figure 62 presents the results. Interestingly, the winner in all elections since 2004 has been the candidate who allocated the larger share of his or her campaign funds to online spending. In this respect, Barack Obama was the first real innovator: at nearly 13 percent, his online spending in 2008 was colossal in comparison with the old school campaign of John McCain that same year. Also striking is the wide gap between the rival campaigns in 2016: whereas Hillary Clinton spent less than 6 percent on internet publicity and other online campaign costs, the equivalent figure for Donald Trump was nearly one-quarter. No less remarkable is the fact that, in the last three UK general elections (2010, 2015, and 2017), UKIP (UK Independence Party) candidates spent on average more than one-fifth of their campaign funds on advertising, mainly on the internet, compared with less than 10 percent for the Liberal Democrats and around 12 percent for the Conservatives and the Labour Party.

As I said in Chapter 4, government control over public media does not seem the right way to correct the imbalance in favor of the private media empires. Similarly, the creation by political movements of their own media will not solve the democratic problem with which we are presently confronted. To be sure, political movements are fully justified in wishing to create new communications media, such as YouTube channels, that enable them to reach their supporters directly and even to enlarge their base. Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France now has his own YouTube channel, with nearly 400,000 subscribers;34 and Bernie Sanders also created one during the Democratic primaries in 2016. (But in the United States, YouTube is mainly used to broadcast election advertising that viewers have to see before they launch a video—a more effective way of reaching them than TV ads, and less of a drain on campaign spending.) Politicians are right to want to diversify the social media, so that they can know their electorate better and reach out to them. But that cannot be a substitute for independent political and general news media. A candidate’s YouTube channel cannot be considered a news medium; it is nothing other than a means of communication. Today, journalists who work for the news media need to have their independence protected, both from private shareholders seeking to promote their industrial interests and from political parties seeking to disseminate their ideas.

Figure 62. Percentage of campaign spending that candidate spent on the internet (online advertising and so on), presidential elections, United States, 2004–2016

Campaigning in the Old Way

Let us not forget what might be described as the good old campaigning methods, beginning with public meetings and rallies. For although I have said a lot about new technologies, public meetings are still a key pillar of election campaigns, not only locally but even more generally in countries where candidates are not permitted to buy airtime.

It is also interesting to note that in France, where candidates are not allowed to engage in TV advertising, election meetings can be a powerful means of televisual publicity in the age of round-the-clock news channels. This is one of the reasons why they play such an important role. For example, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s rally in Lyon on February 5, 2017—with a simultaneous hologram double in the Paris suburb of Aubervilliers—attracted more than 18,000 curious spectators,35 but that was very little compared with the average of 637,000 viewers (or the cumulative 1,440,000) who followed the meeting live on the BFM TV news channel.

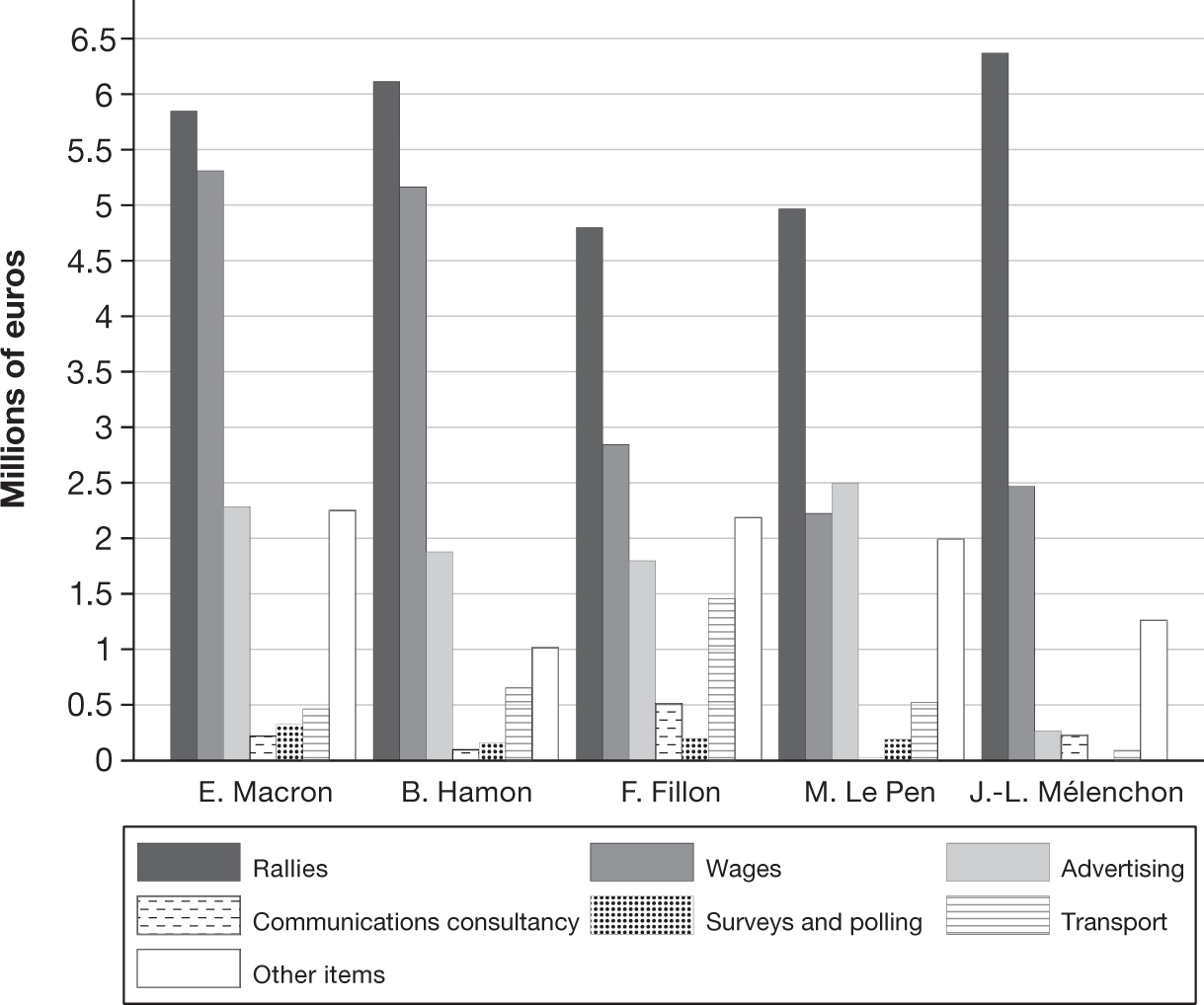

What is the relative weight of these different forms of spending in France? Figure 63 presents the spending by category of the five main candidates in the presidential election of 2017. For the candidates as a whole, public meetings were the principal item by far—above all for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, with his costly holograms, and for Emmanuel Macron, despite the sizable discounts he received. Next came payments for services, which were largest in the cases of Macron and Benoît Hamon, and less significant for Mélenchon, who, in a legal though socially questionable practice, used external providers rather than put a part of his team on the payroll.

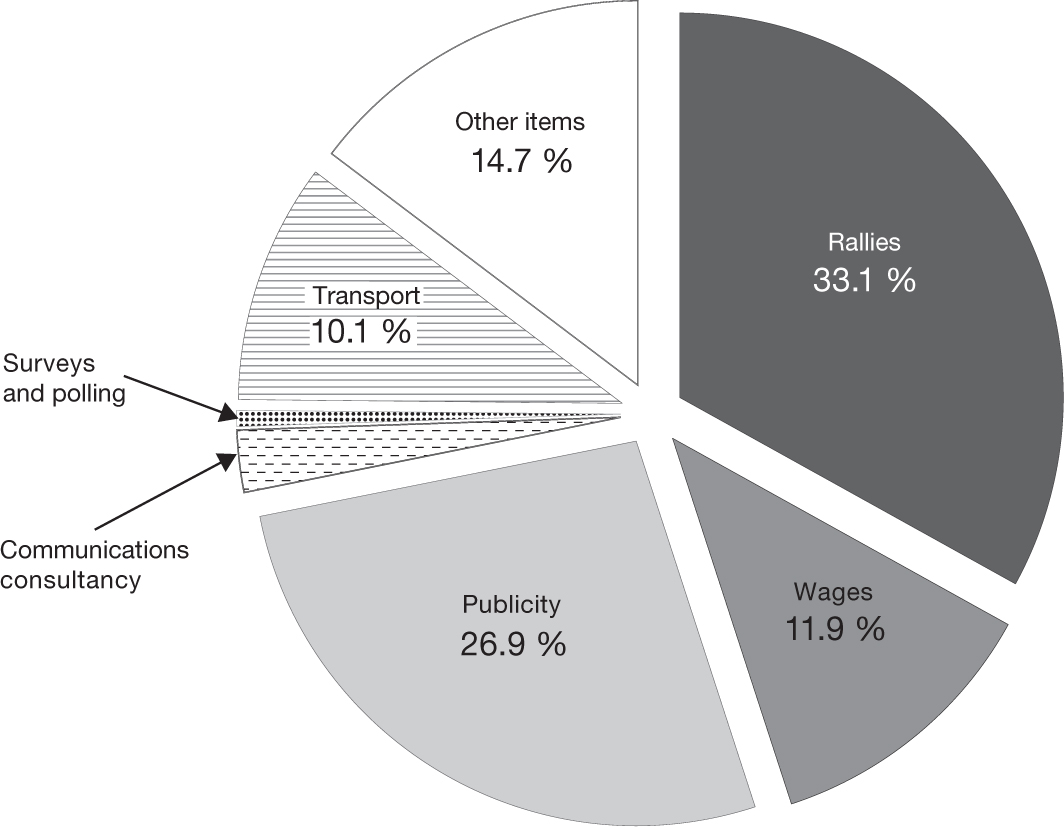

If we now consider all eleven candidates in the 2017 presidential election as a group, taking the average percentage represented by each category of spending, the importance of advertising still stands out (Figure 64). More surprisingly, communications advice occupies a lower place than one might have expected, except for poor François Fillon, who had to deal with the business of Penelope’s dubious remuneration.

Figure 63. Spending of five main candidates in the 2017 presidential election, by spending category, France

Figure 64. Relative weight of spending categories (average of all eleven candidates), France, presidential election of 2017

Figure 65. Relative weight of spending categories, France, legislative and municipal elections

A final point in this review of election spending, however, is that the great weight of public meetings is peculiar to presidential elections. It does not apply to local contests, including parliamentary elections, where advertising (or “printed propaganda,” as it is known) is by far the largest item, as Figure 65 shows for the most recent legislative and municipal elections.

Funding Democracy and Election Spending: The New Property Qualification

Democracy is one person, one vote. Or at least it should be.

Apart from the question of women around the world and blacks in the United States,36 self-styled democracies for a long time set strict conditions, particularly related to income and assets, for inclusion in the electorate, and other restrictions were often in place to limit the number of citizens permitted to run for public office. The justifications given for such practices were many and various, since rulers never lack the imagination to legitimize the power in their hands. One common argument, for example, was that to allow only property-holders to stand in elections was a way of guarding against corruption.

This is no longer the case today. And yet, what has Part Two of this book told us if not that the present system seems to revolve around a plutocratic conception of democracy? One euro, one vote. The private funding of democracy has become the new “property qualification.”37 It seems difficult to characterize the system in any other light. To be sure, there are no longer formal barriers to participation: everyone is permitted to vote and to run for office. But the representation deficit takes a more perverse, because less transparent, form insofar as campaign contributions partly determine election results and—even graver—the reality of representation.

What is the difference between the “double vote” law of June 29, 1820—which allowed French voters who paid the highest taxes to vote twice38—and the present situation under which the richest groups in society can express their political preferences two, three, or even four times through the medium of electoral spending? The only difference is the hypocrisy of the existing façade, which claims to give everyone the same weight in the democratic process, much as the shroud of educational merit is used to make us believe that inequalities are just.39

In the French and similar systems, not only are the rich allowed to vote more than once, but the taxes of all the less well-off are used to finance the multiple votes of the rich. It is a kind of reverse redistribution, which can also be found in different forms in Italy and Canada.

Let us stop lamenting. It was important to establish how things stand today in our democracies; that has now been done. Yes, money captures the democratic process, placing a question mark over the very reality of representation. Yes, this is directly reflected in the public policies that are pursued on a daily basis—policies that, mirroring the ultra-flexibilization of the labor market or the multiple tax breaks given to the rich, put the preferences of the rich into effect, against the interests of the least well-off. Yes, the political choices of the past few decades have led in both Europe and North America to a paradoxical system in which the majority vote on paper, but an ever smaller (and richer) minority actually decide.

But the time for lamentation is over—especially as it is possible for us to act.

Yes, we can change things and save democracy from the grip of money that is not only tolerated but promoted by the regulations in force today. Yes, we can save democracy from all the populisms that have chosen the path of rejection, the worst response to the crisis of representation.

How can we do this? I will try to provide some answers in Part Three, which is given over to solutions. The first urgent task is to reshape the public funding of democracy by making it more reactive and more in keeping with the realities of the twenty-first century. In the internet age, four or five years are not needed to create a political movement: a new one can take shape in just a few months. But if it is not given proper support, a burst of democratic energy may run short of funds and peter out. Public funding must be placed on an equal, democratic, and annual footing. This is what I propose with the idea of Democratic Equality Vouchers worth seven euros each, which each citizen is entitled to receive and can allocate to a political movement simply by marking the appropriate choice on his or her tax return. This modernized public funding would have to go together with strict limits on private funding—otherwise, all its democratic impetus and beneficial effects would be drowned beneath a flood of private donations.

The equality of all citizens in the funding of democracy is a first essential step to solve the representation crisis. But the crisis is such that it would not be enough. It is necessary to go farther and use the instruments of the law-based state, so that tomorrow the men and women who represent us are more like the great body of citizens. This could happen through the introduction of genuine social representation in the national assembly. In Chapter 11, I propose that this should become a mixed assembly where, along with deputies elected in the ways existing today (in France, a simple, constituency-based, first-past-the-post system), a third of the seats are reserved for members elected by proportional representation on lists consisting of at least 50 percent working-class citizens (in fixed jobs or in insecure forms of employment). In other words, the composition of the assembly would reflect the social-economic reality of the country, in a manner not unlike that of the male-female parity lists already in use for regional elections in France. For in order to combat today’s representation deficit, the twenty-first-century legislator must match the citizens whose interests he or she is supposed to represent, no longer chasing after money but trying to convince the majority by means of argument. The laws that such a legislator enacts will no longer address the preferences of the rich and only the rich, but will correspond to those of the great body of citizens.