CHAPTER ONE

Beef Cattle: A Primer

Understanding the basics of cattle evolution, biology, and behavior can provide valuable insight into selecting the right cattle for your farm and caring for your new livestock. Here’s a brief history of cattle and an overview of cattle types, breeds, and traits.

OUT OF ASIA, INTO THE WILD WEST

Bos primigenius, the massive ancestor of all modern cattle, stood up to six feet tall at the shoulder and wielded a spectacular set of horns, with a tip-to-tip span of up to ten feet. Herds of these wild prehistoric bovines—or aurochs as they’re commonly called—roamed throughout North Africa and most of Europe and Asia, following the melting glaciers of the last Ice Age northward. Between 500,000 and 750,000 years ago, long before humans appeared on the scene, the intimidating aurochs split into two distinctive subtypes, the taurine and indicine (or typicus and indicus) varieties of cattle. The humped, droopy-eared indicus multiplied in the eastern portions of the aurochs’ range, while the humpless taurine, whose ears stand out at the sides rather than flop, spread through the Middle East, northern Africa, and Europe. Their domesticated descendants are the droopy-eared indicus breeds that dominate Asia and are popular in the southern United States as well as the familiar taurine breeds that are common throughout Europe and North America.

Probably because they were so large, well armed, and willing to defend themselves, aurochs were rarely hunted by early humans and were domesticated after goats, sheep, and pigs were. But humans seem to have learned early on to love the taste of beef despite the difficulty of obtaining it. Eventually, they figured out that it was easier to raise, than to hunt, cattle and became ranchers. Cattle bones found in archaeological digs in southwestern Turkey show that between eight thousand and seven thousand years ago, the taurine-type cattle eaten by ancient villagers began decreasing in size, evidence of domestication. These early ranchers clearly selected small, docile animals less likely to charge their owners or disappear in the middle of the night.

A pair of bulls carts hay through downtown Weymouth, Nova Scotia, in this old photo. Cattle have historically been used as draft animals as well as sources of meat and leather.

While Middle Eastern farmers appear to have been the first to domesticate cattle, farmers elsewhere probably did so not long after. Many researchers believe indicus-type cattle were domesticated separately in Asia. A more controversial theory argues that taurine-type aurochs were also domesticated separately, by North Africans, and later mixed with immigrant indicus to give rise to the distinctive sanga cattle breeds of Africa.

Early Middle Eastern farmers used cattle solely for meat and leather and kept far fewer cattle than they did sheep and goats. When humans began migrating into the heavily forested and much colder regions of northern Europe, they quickly found themselves much more dependent on cattle. On the move north, goats could not pack as many of their owners’ possessions on their backs as cattle could, and once people arrived in the new land, neither sheep nor goats were of much use in clearing forests or pulling plows in the heavy soil. As farming spread north, cattle—which are not fussy eaters and not overly bothered by predators and actually seem to like the cold—quickly became the most important livestock species. Oxen (castrated adult male cattle) became northern Europe’s primary source of transport and farm power. They remained so until about two hundred years ago, when horses and then the internal combustion engine took their places in most regions.

By three thousand years ago, cattle keepers from Egypt to England had figured out that a cow that pulled a plow or a cart could also furnish milk for the family. Thus the dual-purpose cow and the dairy industry were born. Cows and oxen no longer able to work provided their owners with a large amount of highly nutritious and palatable beef and hides for leather goods.

When English and Dutch settlers brought their cattle to North America in the early 1600s, they adapted their ways of keeping cattle to their spacious new environment. All along the East Coast, cattle not needed for milk or labor were turned into the woods for the summer and rounded up in the fall. Each animal had its ear notched in a way particular to its owner, who had to register his brand with the town officials. In the fall, excess cattle were assembled in herds and a drover hired to walk them to the freshmeat markets in big towns such as Boston and Philadelphia.

Did You Know?

Domestic cattle, which belong to the genus and species of Bos taurus, have no wild siblings. The last known wild aurochs, or Bos primigenius, a cow, died in Poland in 1627. Other members of the bovine group are bison and yaks. Sheep, goats, and pigs are more distantly related, belonging to the same family, Bovidae, as cattle.

Young Herefords fatten up on alfalfa hay in a California feedlot.

Beef cattle need lots of pasture, and as human settlers multiplied, unclaimed land became scarce. Beef cattle producers pushed farther and farther west in search of the necessary cheap grazing. This made for a longer walk to market in the fall, resulting in skinny cattle. Since fat is what makes beef taste good, a finishing industry grew up near the meat processors, where the cattle could be penned and fattened. As the corn belt of the Midwest developed in the nineteenth century, cattle coming from summer grazing farther west were fattened on excess corn there through the winter and driven farther east to market in the spring. In the 1870s, railroads and then refrigerated railcars reached the Midwest, and the beef processing industry found it more expedient to process cattle in nearby towns, such as Chicago, then ship the finished products to the East Coast, than to ship live cattle.

By the time of the Civil War, the center of beef cattle production—the cow-calf operations that produced the young cattle for finishing—was moving into the Great Plains, where the herders mounted horses and became cowboys. The cows they herded were Longhorns, left behind by the thousands when their owners, from the Spanish missions and haciendas of Texas and California, left for Mexico after the Texas Revolution of 1836. Most Americans think of westernstyle ranching as uniquely American, but it really began with the Spanish colonists and their Mexican vaqueros, the first cowboys.

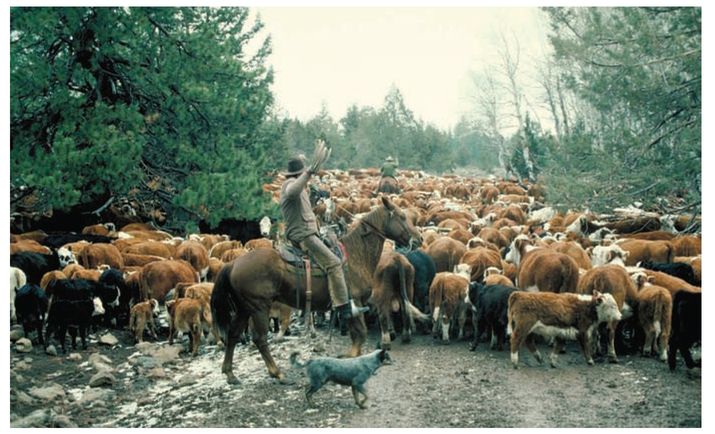

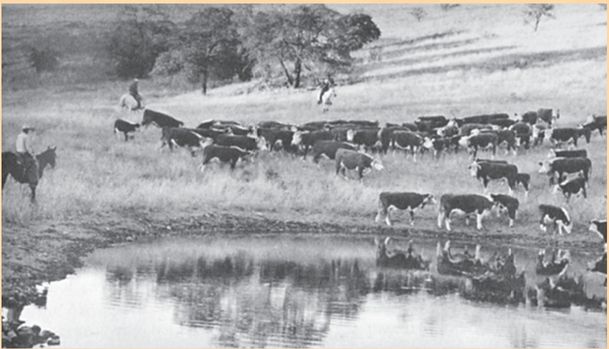

Near Paisley, Oregon, a cowboy drives a herd from summer range to winter pasture. Cowboys on horseback still move cattle in some parts of the country, especially out west, where the terrain can be rugged and the distances long.

During the Civil War, many cowboys and ranchers joined the military and headed east, leaving the cattle to fend for themselves. While eastern herds were decimated by hungry soldiers and civilians, the western Longhorns ran wild and multiplied. When the war ended, there weren’t enough cattle left in the East to satisfy demand, let alone supply the wave of soldiers and miners now moving west, and by 1866, beef cattle prices were 200 percent higher than they had been before the war.

Texas rancher Charlie Goodnight returned from the war to find that the 180 head of cattle he’d left behind had grown to 5,000 grazing in the area. Although the cattle weren’t worth much in Texas, reports were trickling back of Longhorns bringing an incredible $40 per head in the right market, including the Northwest. In the Northwest, the U.S. Army had forts full of soldiers in need of food and far from any food sources. Goodnight looked up his friend and veteran cattleman Oliver Loving to help, and they rounded up two thousand head of cattle. The pair hired eighteen riders and headed north, edging the Chihuahua desert, crossing rivers, fighting Indians, and turning stampedes. At Fort Sumner in New Mexico Territory, the herd was sold to government provisioners. Goodnight netted the princely sum of $12,000, and the golden age of cowboys and cattle drives was born. Cattle were king.

Did You Know?

Historically, the term cattle was used to refer to all varieties of four-legged livestock, including horses, goats, and sheep. When referring specifically to bovines, ranchers used the term neat cattle. Only in the past 100 to 150 years has the meaning of the word cattle changed to refer only to domesticated bovines of the Bos genus.

Cattle in Myth and History

Cattle stampede across the 5,500-year-old cave paintings at Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, pull a cart in a 2,600-year-old bas-relief from Nineveh in Mesopotamia, and power a plow in a 1,750-year-old Roman tile mosaic from Saint-Romain-en-Gal in France. Clearly, cattle have been an integral part of human lives, art, and culture in North Africa, the Middle East, Asia, andurope for a long, long time. Not only have humans used cattle for labor, milk, and meat, but they have also counted the animals as wealth and status and have revered them in myths and religious beliefs.

Ancient Greek and Roman myths often involve cattle. Heracles (Hercules) subdued the great fire-breathing bull of the island of Crete and stole a herd of red cows from the monster Geryon. Crete was famous for bull worship and for being the home of the mythical Minotaur, half-man and half-bull, that lived on human flesh and terrorized a labyrinth under the palace of Knossus.

In India, cattle have been an integral part of daily life and the Hindu religion for several thousand years. A constant presence in ancient art and in rural areas, the sacred cattle of India are traditionally milked and worked, but not eaten, by higher-caste Hindus, who believe many gods and goddesses reside in cows.

In the United States, the myth of Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox arose from the thousands of loggers who felled the forests of the Northeast and the Midwest, hauled the logs with teams of oxen, and then made up stories around the campfire during long winter evenings.

The tall, silent cowboy trailing his herd into the sunset is one of the great American cultural icons, even though, according to cattle industry historian Jimmy Skaggs, “relatively few of them were the strapping Anglo-Saxon stereotypes of film and fiction.... [M]ost of the adult men on trail drives were Mexicans, blacks, and Indians . . . and even a few adventurous young women, some of whom were disguised as young boys.” (The Cattle Trailing Industry, 1973.)

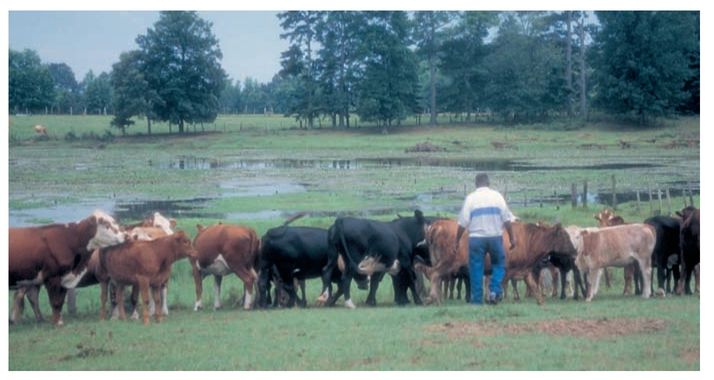

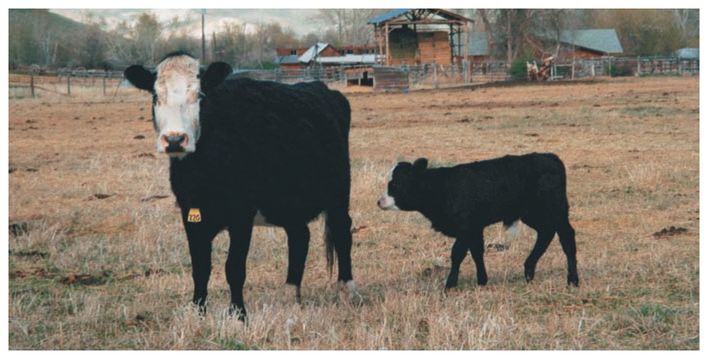

A cattle owner works in the pasture with his mixed breed herd. Small producers typically have mixed, or commercial, herds, which comprise a variety of breeds and mixed breeds, rather than purebred herds.

From that time until the mid 1880s, when a combination of drought and fierce winters nearly wiped out the West’s range cattle, one hundred million beef cattle traveled the four great trails: the Goodnight-Loving, the Chisholm, the Shawnee, and the Western. Fortunes were made, legends were written, and the practical beef cow acquired—by way of the cowboy, the cattle drive, and the Hollywood Western—an aura of myth and romance that still warms the hearts of ranchers today.

This mythology has also left many people with the impression that cattle were primarily raised on large ranches. Stepping back from the legend and looking at the figures offers a slightly different picture of the U.S. beef industry. Even at the height of the ranching boom in the early 1880s, the big operations raised only 14.4 percent of the beef cattle sent to market. The majority of beef cattle in the United States always have been, and still are, calved on small farms and ranches into relatively small herds. Small farmers are cowboys, too!

BEEF CATTLE: THE BASICS

For hundreds of years, people have bred cattle to develop characteristics that were best adapted to a particular climate and purpose. Eventually, this resulted in distinctive breeds of cattle, each with a distinctive palette of physical traits. Today, a cattle buyer can choose from a wonderful array of color, build, size, growth rate, and potential meat and milk production to fit cattle to the farm, the climate, and the purposes of the owner.

Although not all cattle are created physically equal, they do share general behavior characteristics. Cattle sense the world differently than we do. They eat different foods and digest them differently. Understanding how cattle operate is key to knowing what to expect from them, what they will like and won’t like, and to getting them to do what you want them to do. Understanding and working with cattle’s natural behaviors will result in calmer, healthier animals.

BEEF BREEDS

Until the middle of the eighteenth century, cattle were tough, multipurpose animals that were not selectively bred for any specialized purpose. Differences in their sizes, colors, and builds were simply a result of groups’ being isolated from one another in remote settlements. Then in 1760, Robert Bakewell, an Englishman, began the first known systematic breeding program to improve the uniformity and appearance of his cattle. The results were published in 1822 in George Coates’s Herd Book of the Shorthorn Breed, the first formal recognition of a cattle breed. Other breed herd books soon followed, and as the concept of breeding for a specific purpose spread, cattle were divided into two main categories: those bred primarily for milk production and those primarily for beef production. Even the original dual-purpose Shorthorn breed has now been split into Shorthorns for beef and Shorthorns for milking.

More than five hundred breeds of cattle exist in the world today, although only a few are common in the United States. Milking Shorthorn, the ubiquitous black-and-white Holstein, and the rarer Guernsey, Brown Swiss, Ayrshire, and Jersey make up the six primary dairy breeds in the United States. There are several other minor dairy breeds as well. All dairy breeds produce excess bull calves that are raised for beef, and plenty of beef operations are built on dairy calves.

Did You Know?

Three breeds of cattle possess the attractive and very distinctive “Oreo cookie” coloring—black except for a broad white band around the middle: the Dutch Belted, the Belted Galloway, and the Buelingo. The breeds differ from each other, however, in their other characteristics and in their uses. The Dutch Belted were a prized dairy breed in the United States until about 1940, while the Belted Galloway, probably descended in part from the Dutch Belted, is primarily a beef breed. The Buelingo is a uniquely American beef breed developed during the 1970s and 1980s by North Dakota rancher Russ Bueling, primarily from Shorthorn and Chianina genetics.

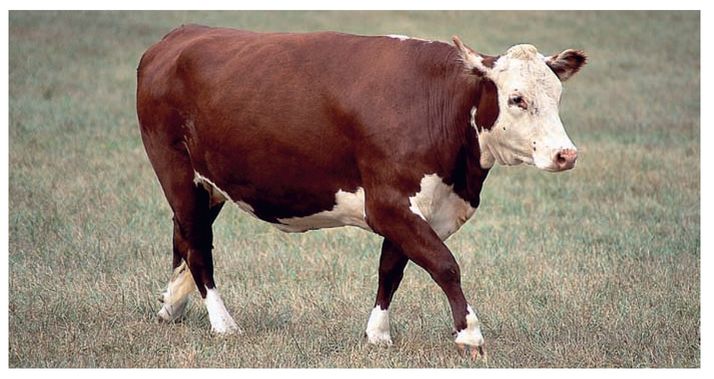

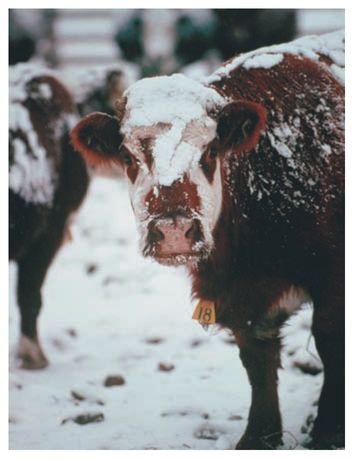

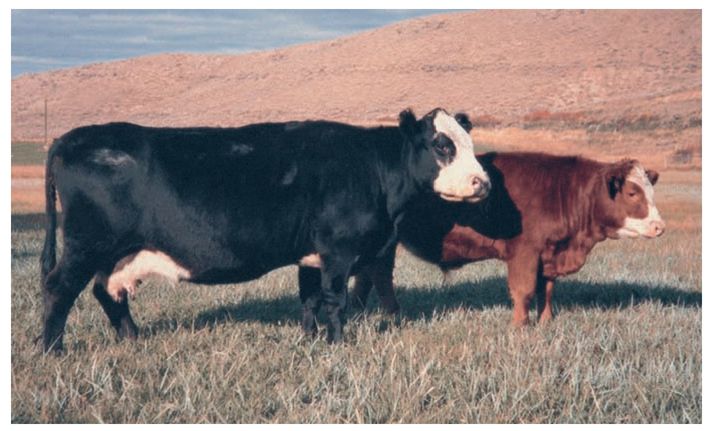

Herefords such as this one have dominated the U.S. cattle industry for more than a hundred years and have a well-deserved reputation for being docile and easy on the feed bill.

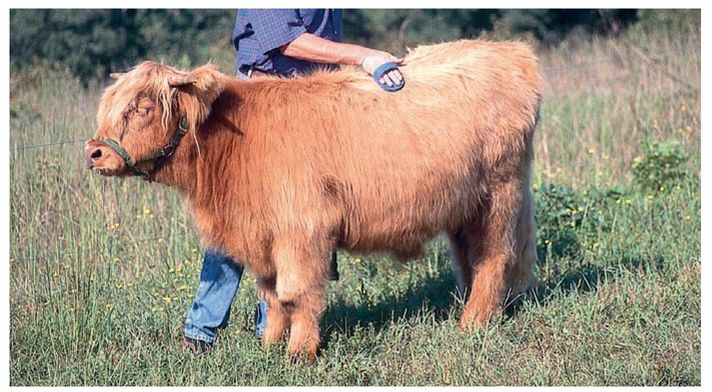

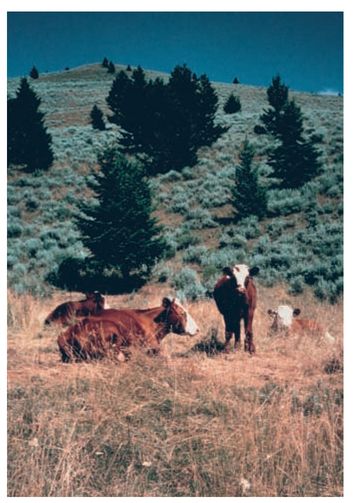

Hereford cattle, with their familiar white faces, red bodies, and white markings, have been the backbone of the U.S. beef industry since a few decades after their arrival in 1847. Black Angus, first brought to the United States in 1873, are now almost as numerous as Hereford; while that breed’s offshoot, Red Angus, established its own breed registry in the mid-1900s. These three breeds, along with the Shorthorn, Scottish Highland, Dexter, Devon, and Galloway breeds, are the major British breeds of beef cattle, so designated because they all originated in England, Scotland, Ireland, or Wales. In general, the British beef breeds are smaller, fatten faster, and are more tolerant of harsh conditions than the continental breeds.

This sturdy Charolais heifer has a big frame and will produce a lot of beef in a single package.

A long-haired Scottish Highland calf enjoys a good brushing from his owner.

The continental breeds from Europe are generally larger and slower to mature but offer a bigger package of beef to the producer. The most common are the Charolais, the Limousin, and the Saler from France; the Simmental from Switzerland; and the Gelbviehs from Austria and West Germany.

In the United States, new breeds have been developed that tolerate southern heat better than do the European imports. The famous Texas Longhorn, which pretty much developed on its own from Spanish cattle brought over by colonists, provided the starting foundation for American ranching. The American Brahman was developed from indicus-type imports and then was crossed with different European breeds to create the Santa Gertrudis, the Brangus, the Beefmaster, and several other uniquely American cattle breeds.

When well cared for, any breed of cattle will produce good beef. Look for a breed suited to your climate and pasture type and, if the income is important, to the prospective buyer of your beef. Auction barn buyers and finishers will have definite preferences. Most important, get something you like. You may fall in love with the Oreo cookie markings of the Belted Galloway, the shaggy look and big horns of the Scottish Highland, or the gentle disposition of the Hereford.

CATTLE BIOLOGY

Cattle are ruminants, members of a class of grazing animals with four-chambered stomachs adapted to digesting coarse forages other animals cannot utilize. Consequently cattle—as well as sheep, goats, and horses—can make use of land too rough, rocky, dry, or wet to grow crops for humans.

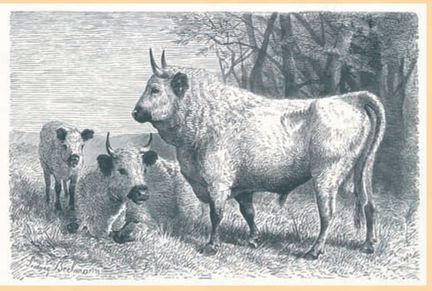

Endangered Breeds

Of the hundreds of cattle breeds adapted to an enormous range of climates and conditions throughout the world, many are now endangered. The American Livestock Breed Conser-vancy lists eighteen breeds in the United States that need help to survive. On the ALBC “critical” list, defined as breeds that have fewer than 200 registrations each year, are the Ancient White Park (above), the Canadienne, the Dutch Belted, the Florida Cracker, the Kerry, the Milking Devon, the Pineywoods, and the Randall. On the “threatened” list, with fewer than 1,000 U.S. registrations each year, is the Red Poll. The “watch” list, with fewer than 2,500 registrations, includes the oncepopular Ayrshire, Guernsey, and Milking Shorthorn, as well as the Belted Galloway, the Dexter, and the Galloway.

Cattle pick their meals by smell and taste, then graze until the first chamber of the stomach, the rumen, is full. Because they have no front upper teeth, just a hard pad, they tear the grass instead of biting it. (This is also why cows don’t normally bite people.) Watch a cow grazing, and you’ll see her grip a bite of grass between the pad and the lower front incisors, then swing her head a little to rip it off.

The long muscular tongue, as rough as sandpaper, is useful in quickly conveying grass back to the throat. The tongue is also used for grabbing grass, for licking up those last bits of grain, and for a little personal grooming (although cows aren’t flexible enough to reach around too far). Copious amounts of saliva—up to fifteen gallons a day for a mature cow—moisten the grass so it slides easily down the throat. Let a bottle-fed calf suck your finger, and you’ll be surprised at how strong, rough, and slimy that tongue is.

Once the rumen is full of pasture grass or hay, the cow will lie down in a comfortable spot and, mouthful by mouthful, burp it all back up again. Because she initially swallowed without chewing, the cow now brings those huge rear molars into play and takes the time to grind up the grass into a slimy pulp before swallowing it again, this time into the second stomach chamber, the reticulum. Chewing her cud, as this process is called, takes eight to ten hours each day and involves up to forty thousand jaw movements.

From the reticulum, the cud moves into the omasum and next to the abomasum, the true stomach, then down the intestines. What’s not absorbed comes out the back end. Because a cow’s diet is high in fiber and fairly low in nutrients, an awful lot comes out the back end, ten or twelve times a day, for a grand total of up to fifty pounds of manure every twenty-four hours. When the grass is young and lush, the manure is almost runny, like cake batter. When cows feed on mature pasture or hay, the manure is drier and more solid.

Along with all undigested organic matter and dead gut bacteria, cow manure often carries the eggs of internal parasites, or “worms,” as most people call them. Cows won’t graze near their own manure, an evolutionary response to the parasite problem. But cattle show no discretion as to where they poop, so pastures need to be large enough or rotated often enough that the cattle don’t foul the grazing areas to the point that nothing is edible.

In addition to the manure deposits, cattle urinate eight to eleven times a day. Both manure and urine are superb fertilizer for pastures. Although the cattle won’t graze those areas right away, they will after the deposits decompose.

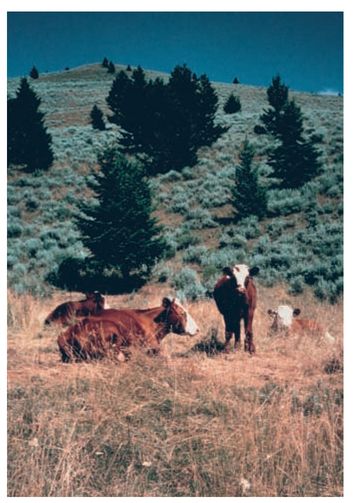

Having spent the early morning grazing, these cattle now lie around leisurely chewing their cuds, not moving much during the heat of the day. Ruminants usually eat a lot of feed in a hurry, then find a quiet place to rest and digest.

Because cattle need to spend so much time resting and ruminating, they’ll graze for only about eight hours a day. (When it’s hot, they do much of their grazing at night.) The higher the quality of the pasture or hay, the easier it is for cattle to get enough to eat in those eight hours and to gain weight and bear healthy calves. Young, lush pasture is their favorite food, high in musclebuilding and milk-making protein. If it’s too young and too lush, however, pasture can cause problems. Cattle digestive systems are set up for lots of fiber, which young pasture and legumes, such as clover and alfalfa, lack. Too much of this type of feed can pack the rumen so tightly that digestive gases can’t escape, and the cow begins to bloat. If the bloat isn’t treated quickly, it will put such pressure on the cow’s lungs that she won’t be able to breathe, and she’ll die. For this reason, you should never put cattle on wet or frosted legume pastures and should always provide some dry hay in the spring when pastures are just greening up. Bloat is a fairly common killer of cattle, although it’s more common among dairy cattle than beef, due to the much richer diets fed to dairy cattle. Just as in humans, a rich diet seems to create a higher potential for digestive upset.

With lush grass to graze on, this cow can produce plenty of milk for her plump calf. Good pasture results in good cattle.

Older pasture and hay composed of mixed grass and legumes are lower in protein but higher in carbohydrates. This keeps cattle digestive systems in better order, helps fatten the cattle, and keeps them warm in the winter. It is also healthier for pregnant and nursing cows. Mother cows can get too fat on rich pasture, which is hard on their feet and legs and may contribute to difficult calving.

HOOVES AND HIDE

Good feet and legs are important in all cattle. Cows have cloven (two-part) hooves that average around three and a half by four inches. If a cow weighs a thousand pounds, that’s a lot of weight coming down on that little hoof every time she takes a step, and she takes a lot of steps in a day to get food and water. Cattle don’t like mud or slippery surfaces because they can fall and hurt themselves; they will walk around bad footing if they can. Cattle hooves grow continuously, and long hooves cause lame cattle. If the herd is getting enough exercise, however, their hooves should not get too long. A few rocks in the pasture will help keep hooves worn down.

Cows also use their hooves to scratch themselves and to kick. They can kick both sideways and backward, and they’re quick as lightning. If they have horns, they’ll also use these to defend themselves, and a horn can do even more damage than a hoof. For this reason, many cattle owners prefer polled, or naturally hornless, cattle. You can also dehorn calves when they are quite young so that their horns never grow.

For pests that are too small to kick, such as biting flies, cattle have long tails for flicking them off, and their thick hides protect them from some insect species. But several kinds of flies can bite through a cowhide, and some will even bore a hole in the hide and lay eggs there. The irritation and discomfort caused by flies can slow weight gains in calves and keep cows miserably bunched on a hot day to minimize skin exposure to the tormenting flies.

To stay warm in cold climates, cattle will grow a longer winter coat. Unlike most dairy cows, beef cows will have hairy udders.

HOW CATTLE SENSE THE WORLD

Cattle have excellent eyesight, but it works a little differently from human sight. They can see color to some extent, and they see exceptionally well in the dark. Because their eyes are spaced so far apart, their horizontal vision (side to side) spans an amazing 300 degrees at a time, with their only blind spot directly behind them. However, their vertical (up and down) range of vision is limited to 60 degrees, which means they have to look down to see where to put their feet when the footing is unfamiliar. What’s more, their eyes work somewhat independently of one another, rather than in concert as our eyes do, which gives them poor depth perception. When herding cattle, it is important not to work directly behind them; they can’t see you there and will either turn to look at you or spook and run away. When moving cattle into a new area, give them plenty of time to see where to put their feet.

Long hair and a layer of fat keep this steer so well insulated that not enough heat escapes to melt the snow on his back and head.

Cattle’s sense of hearing is acute, and they can swivel their ears around to hear even better. They dislike loud noises, especially loud sharp noises such as yells from handlers. They get upset and panicky when their handlers start shouting; but they are soothed when you talk to them softly or sing a little. Skip rock and roll, however, and go for soft ballads.

Biological Traits

Temperature: 101.5 degrees Fahrenheit

Pulse: Adult—60 to 80 beats per minute; calf—100 to 120 beats per minute

Respiration: 10 to 30 breaths per minute

Natural life span: twenty years or more

Adult body weight: Cows—800 to 1,700 pounds; bulls—1,000 to 2,600 pounds

Sexual maturity: Heifers can reach sexual maturity as early as four months but should not be bred until they’re at least fourteen months. Bulls should not be used for breeding until at least one year of age.

Heat cycle: Cows will cycle every seventeen to twenty-four days (the average is twenty-one days), with the actual heat (period of time when the cow is capable of becoming pregnant) lasting one to one and a half days.

Gestation: Nine and a half months, or 285 days, give or take a week or two.

Color: Cattle may be black, white, red, all shades of brown, or any combination of those colors.

Coat: Nearly all cattle have short, shiny hair but will grow a somewhat longer, thicker coat in winter. A few breeds, such as the Scottish Highland, are naturally long haired.

Cattle use quite a bit of verbal communication. They know one another’s voices, and they’ll learn yours. They’ll bellow for feed, bawl for their calves, and moo back when you call them. A cow has a special low moo for when her calf is fed and settled and all’s right with the world.

Cattle have a superb sense of smell, which they can use to follow the trail of their calves and to tell different plants apart. They also have a strong sense of taste and, as a result, have strong preferences for some plants over others. Research by Utah State University professor of rangeland science Fred Provenza has demonstrated that calves learn their plant preferences from their mothers and remember them all their lives. Year after year, they’ll seek out their favorite grazing spots. We have one small patch of bluegrass that always gets grazed to the ground before anything else is touched, although it looks no different than any other bluegrass!

CATTLE BEHAVIOR

Although they are not as bright as dogs and cats, cattle are intelligent in their own way. Usually good at taking care of themselves, they’ll find a windbreak when it’s cold and shade when it’s hot, and they’ll never forget where the calves are. While cattle learn more slowly than horses, they do quickly learn to come when called if you reward them with grain or a new pasture when they get there. When they learn something, they never forget it—especially bad experiences, an important point to remember when you’re working cattle. If you are patient and give them time to think things over, they can be taught quite a bit. When introduced to new experiences slowly and quietly, they’re also quite curious. If I walk into the pasture and sit down, I’m soon closely surrounded by a ring of sniffing cows, wondering what in the world I’m doing. (If you ever wondered what cow’s breath smells like, give this a try.)

Mother and baby know each other best by smell—the most important “social sense” for cattle.

Cattle are not democratic. In every herd, there is a hierarchy, from the bossy top cow to the shy one at the bottom of the pecking order that always gets shoved away from the best feed. Dominance is determined by strength and aggressiveness, but it’s all kind of low key. Cows don’t fight so much as they test to see who can push whom around. You’ll sometimes see a pair of cows head-to-head, hooves planted, just pushing. The winner is the one that pushes hardest and longest. Cows will push around a young bull, too. (Don’t worry, he’ll get over it.)

Cows have different personalities. One of the delights of having a small herd of cattle is getting to know each cow on an individual level. Some are inherently nervous and will never let you get close. Some are docile and like their heads scratched, while others like to spend most of their time shoving everyone else around. Some are overprotective mothers; others are lackadaisical about their calves. Most will nurse only their own calves. But a few will let any calf help herself—kind of like those human mothers we fondly remember from our childhoods who would feed any of the neighborhood kids who happened to be around at dinnertime.

Two young bulls engage in a head-to-head pushing contest. Such encounters are a common way for cattle to determine who’s going to be higher up in the herd pecking order.

Some behaviors are common to all cattle. Because they are, and always have been, a prey species, cattle are hardwired to run at any sign of danger. Danger to nervous cows could be anything from a strange human in the pasture to a funny smell. They don’t stop to think about whether there is really a threat; they just take off. They’ll run right over you if they’re in a panic, and they panic fairly easily. For animals that are normally fairly slow moving and clumsy, they can move surprisingly fast when frightened or agitated, and they’ll jump gates and fences—or trample them.

Cattle would rather run than fight, but they will also fight if they have to. A cow will defend her calf; a bull that decides for some obscure reason that you’re competition or a threat will charge you and kill you. Although when kept with the cows beef bulls will usually behave themselves and run away with the cows, they are naturally more aggressive than cows, and they are unpredictable. You can’t trust a bull not to charge you instead of running away. Never, ever, turn your back on a bull.

As a prey species, cattle learned long ago that there is safety in numbers. They graze in a group because it’s easier for a group to spot and defend itself against predators than it is for a single animal. The herding instinct is not completely dominant, however. Groups of two or three will wander off from the main herd in pursuit of some promising grazing, although usually not too far.

Advice from the Farm

Cattle Benefits

Ranchers discuss some of the benefits of owning cattle.

Gentling the Stream Bank

“I was trained that grazing cattle along streams was wrong. But as I watched, I saw the stream start to change in the fenced-off section. I saw erosion big time. As I watched the rotational grazing along the stream, my eyes told me the cows were gentling the stream bank instead of making it erode. Here, we’re seeing some good stream characteristics. There are fifty or sixty different plant species, good root mass, dense growth, and very little erosion.”

—Ralph Lentz

Creating Biological Diversity

“We have a vision of a biologically diverse farm, where we raise meat in sync with the environment.”

—Juliet Tomkins

Completing the Cycle

“The beef cattle are here to complete the cycle on our farm. For anything to be truly sustainable, you have to have forages and legumes.”

—Helen Kees

Teaching Life’s Lessons

“I have boys, and I think cattle give them a good example of how life goes on. It’s a learning process for the boys. The first calf we got we named Dinner. It’s a way of teaching the facts of life.”

—Randy Janke

Keeping Everyone Happy

“If you keep your cattle happy, and keep your pastures happy, you’ll do pretty well.”

—Dave Nesja

Head up and on the alert, this cow is ready to defend her calf if the need arises.

If the pasture is large enough, cows prefer to go off by themselves to calve and may remain away for a day or two before returning with the new baby. Cows also use baby-sitters. Often you’ll see a single cow watching over a group of calves while all the other mothers are off grazing and, I presume, gossiping.

THE CATTLE PRODUCTION CYCLE

The life of a beef cow or steer follows a pretty standard pattern in most of the United States. After a calf is born, usually in the spring, the infant stays with the mother until it is weaned (between four and ten months of age). By weaning time, a male calf has been castrated and is ready to go on pasture or hay as a stocker calf, or backgrounder, for several months. An older calf may skip this stage and go directly on feed (presumably this is why all weaned calves are called feeder calves). On feed means putting young cattle in a pen instead of a pasture and feeding them a highprotein diet to accelerate growth and fattening. If the steer is an early maturing breed and has been well fed, he may go to slaughter as young as sixteen months of age. If he is a slowermaturing breed or is on a less intensive feeding program, he may be kept until age two or three.

Female, or heifer, calves intended for breeding are kept separate from their mothers and the bull after weaning, usually until they’re fifteen months or a little older. At that point, they’re bred either by using a live bull or by artificial insemination, usually in midsummer of the year after they’re born. Nine and a half months later, if all goes as planned, they deliver their first calves and officially become cows, instead of heifers.

As long as a cow raises a good calf each year and doesn’t exhibit any major personality problems, she’s kept in the herd. When she becomes too old or infirm to become pregnant, the owner culls her. Sending a gentle old cow away to slaughter is difficult. I try to console myself with the knowledge that she had a full and happy life on our place and by arranging for her to go somewhere close and quick.

Bulls are usually kept in groups until they’re sold as breeding stock. The bull’s first calves will be delivered the next year, just ahead of breeding season, so it’s safe to use him for a second year. If you keep a bull for a third year, his daughters will be old enough for him to breed. You need to either make other arrangements for the heifers or get a new bull. Bulls can be sold to other cattle owners to give them a couple more happy years in the pasture or sent to slaughter.

This cattle production cycle creates a lot of opportunities to tailor your beef operation to your personal preferences and calendar. A cow-calf operator is on the job year-round, but it doesn’t take intensive management to keep cows and calves happy and productive. A backgrounder can buy feeder calves in the fall or the spring and keep them on forages until they’re ready for the feedlot. It’s quite easy with this system to have cattle only for the summer, so that you don’t have to make or buy hay and you can take the winter off. Feedlot operators can work on small amounts of land because they don’t need pasture; they do, however, need excellent management skills and a lot of knowledge about cattle nutrition.

Finally, seed stock producers, who raise bulls and heifers for cow-calf operations, must have plenty of experience with breeding high-quality cattle as well as good marketing skills.

This cow’s calf has grown fast through the spring and summer and is ready to wean and possibly to sell or even finish at home.