CHAPTER THREE

Choosing, Buying, and Bringing Home Cattle

With fences, feed, facilities, shelter, water tank, and salt and mineral feeder in place, you’re ready to go shopping for cattle. By this point, you’ve invested more time and money than you would have for any other type of farm animal, except dairy cows, but it will all pay off in cattle that stay home, eat well, and handle easily. From now on, it gets a little easier, and you’ll have less daily work to do than you would for sheep, goats, pigs, or poultry.

You have a few options for where to buy cattle and several choices in what kind of cattle you buy. Fit your purchase to your budget, the size of your pasture, how much time you’ll have each day for chores, and whether you’re interested in beef for your freezer or in building a herd.

Whatever age or sex you buy, the minimum number of cattle you should purchase is two. Cattle are herd animals and hate being alone. They will adopt a goat or a donkey or anything else handy as a companion, but they thrive best when in the company of their own kind. If you’re buying a steer primarily for your own consumption, keep in mind that most families will take a year or two to eat a single steer. So plan on selling the extra steer at the auction barn or the extra half or quarter of beef to friends or relatives.

Following are some general guidelines for choosing and purchasing cattle.

WHAT TO BUY

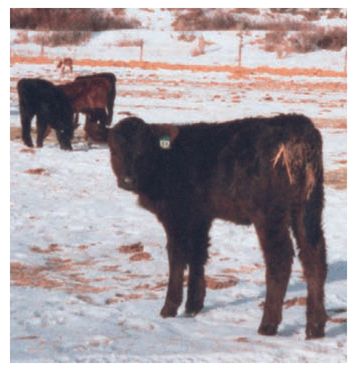

Steer calves purchased in the fall will be ready for butchering when they are between sixteen and thirty months of age, depending on the breed and your feeding program. This means that a male calf bought after fall weaning could be ready for the processor as soon as the following fall. Heifer calves bought after fall weaning will be ready to breed the following summer, provided they grow well through the winter and spring.

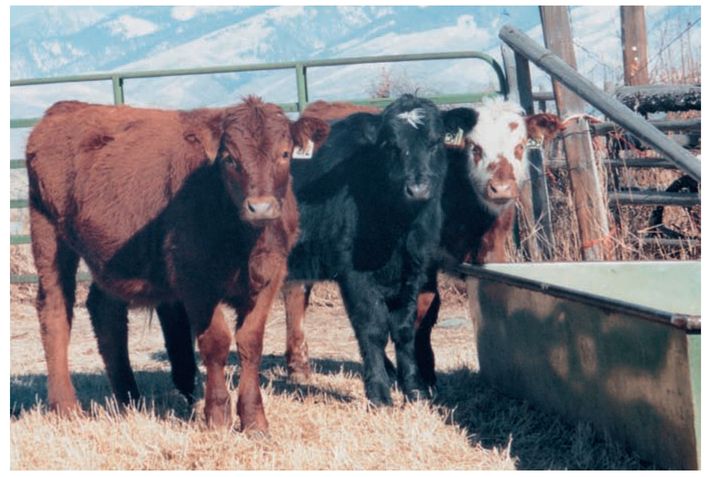

These well-grown steer calves have been moved into the weaning pen and are figuring out the water tank in their new home.

Any calves you buy should have been weaned for at least three weeks. They should also have received a nine-way vaccine, then a booster two to four weeks later. Heifers should be wearing the small metal ear tag that shows they’ve had a brucellosis vaccination. Bend down and look behind steer calves to make sure the castration got both testicles, or you could have a bull on your hands by mistake.

If you want cattle around just for the summer, you can buy steers in the spring and sell them in the fall. If you’re buying for your own freezer or to sell as finished (ready to slaughter) cattle, they should be started on some grain right away. They’ll quickly learn to come running in from the pasture for their daily grain ration.

If you’re buying breeding stock—whether cows, heifers, or a bull—finding high-quality cattle is more important than if you’re raising cattle for processing. Start the search early and take the time to find out about different breeders. If you’re planning on showing cattle or enrolling your kids in the 4-H beef program, look for operations with good show records. If your objective is to get a decent cow-calf herd started, it’s more important to find sellers with calm, clean, reasonably good-looking cattle.

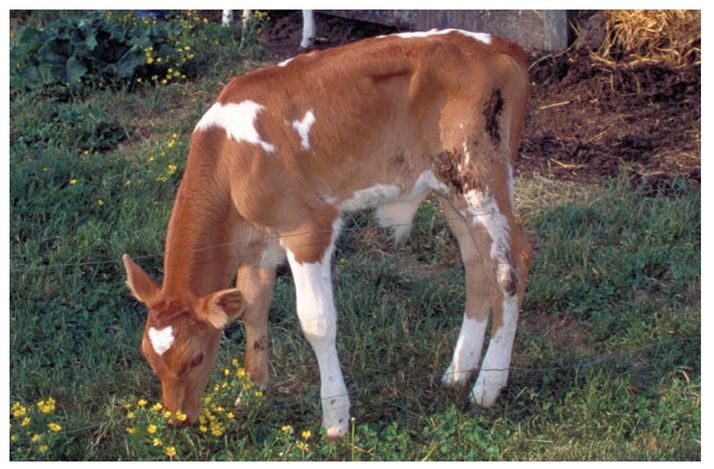

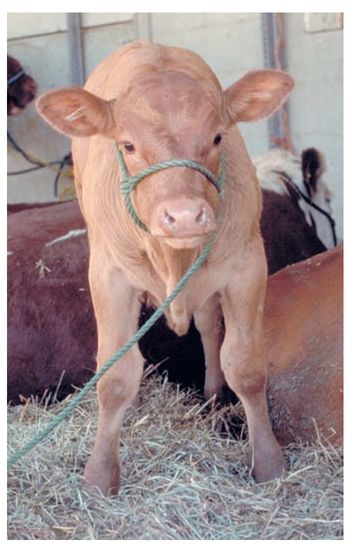

Another option is to buy dairy bull calves. They will produce fine beef. However, it takes a lot more grain to fatten them up, the cuts aren’t as nicely shaped, and there’s a smaller proportion of meat to bone and by-products. Since only cows give milk, bull calves are a waste product in a dairy operation and are generally sold sometime between three days and a few weeks old. Consequently, they aren’t weaned, so you’ll have to bottle-feed them milk until their digestive systems are mature enough to handle grain and forage. Although they’re a lot of extra work, these calves are available year-round, are very inexpensive compared with all other cattle, and can be transported in the back of a van.

Occasionally, you may be able to buy an orphaned beef calf or one that’s been rejected by her mother. Some dairy farmers breed their heifers to a beef bull for easy calving with their first calf, and these half-beef, half-dairy calves are a bargain. Treat orphans or dairy-beef cross calves just as you would a dairy calf.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR IN CATTLE

The only way to acquire an eye for good cattle is to look at a lot of cattle. It takes a few years to develop that eye, but there are some things even a beginner can spot if you take your time and know what to look for. I’m always a little nervous when buying cattle, and I forget things if I hurry so I make a mental checklist. Cattle, too, get a little nervous when a stranger shows up in their pasture or pen. Give them time to settle down again. Lean on the fence or stand quietly in the pasture, and take a good long look at their shape and how they act.

This Guernsey bull calf, even though it’s a dairy breed, will produce excellent beef and is a lot cheaper than buying a weaned beef calf.

Advice from the Farm

Buyer Beware

Our experts offer some advice on buying beef cattle.

Have Patience

“We found someone who was quite willing to sell us two bred cows, for $800 apiece. Hindsight is so clear; I believe now that we paid top dollar for old cull cows. However, the cows were bred, and the sellers were very helpful in guiding us in the care and feeding of the cows and in newborn calf care. The bad part of all this is that within one year we had to butcher both of these cows due to rectal prolapse. With both cows gone and two bull calves left, we bought two nice heifer calves, which is what we should have done in the first place but were too impatient. We now have had four cows for several years, which has been a good number for us. We carry twelve animals over the summer—four cows, four of last year’s calves, and four newborn calves—and eight over the winter, after the four one-and-half-year-olds are butchered.”

—Linda Peterson

Check Looks and Temperament

“I like them so they look straight all the way back on their backbone. There’s almost an edge to them. They look upright, they look strong; it’s almost an eager look. I always check the feet—some cattle, it seems like a hereditary thing, have really long hooves. Temperament is a big thing for me, too, with little kids around. I’ve got one cow with a little bit of attitude, but she’s never offered to come after you. I’ve got another one that’s so meek and mild she always gets pushed back.”

—Randy Janke

Narrow the Focus

“There’s so much going on now with numbers—expected progeny differences, relative this and that—and it’s so far extended that the average young person needs to just focus on one or two things when choosing breeding stock. The ones I strongly recommend are calving ease and temperament. You need to stick with cattle that won’t explode every time you come around.”

—Rudy Erickson.

Know the Seller

“I’ve never bought from a sale barn. We bought private treaty or from a neighbor’s auction where we knew the herd.”

—Dave Nesja

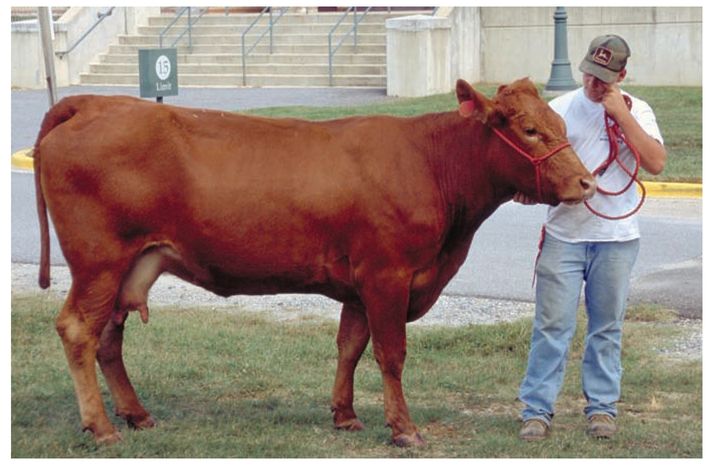

A prospective purchase should be looked over carefully for conformation and good health before buying. A good place to start developing your eye for cattle is at a county fair like this one, where the judges will often explain the good and bad points to the audience, such as the low-hanging udder of this cow.

SHAPE

Whatever the breed, beef cattle should ideally look thick and square, like a big hairy rectangular box on legs. While a dairy cow will look like a wedge, with the narrow part at the front, a beef cow should be blocky. The back should be straight and the line of the belly nearly so, not tapering too sharply up to the hind legs, with a rib cage that is rounded, not flat. The hindquarters should look broad and meaty, especially in steers and bulls, and the legs should be straight. Hooves should be even and short, definitely not so long that they curl upward, and they should point straight ahead.

Watch Them Move

When buying cattle, watch how they move and hold themselves. You should observe no lameness or hunched backs when they walk. Cattle that won’t relax, that keep their heads high and bodies braced, may be wild and hard to handle. Cattle that won’t let you anywhere near them to look them over could be a problem, too, but don’t expect to walk up and pet them either. Unless they’re show cattle, most beef cattle aren’t accustomed to being approached too closely by strangers.

Steers should have thick necks and fleshy forequarters. Cows and heifers should be slimmer through their shoulders and necks and have more feminine heads. Cows should have high, wellshaped udders. Both sexes should have a wide muzzle, indicating that they can take big bites of grass.

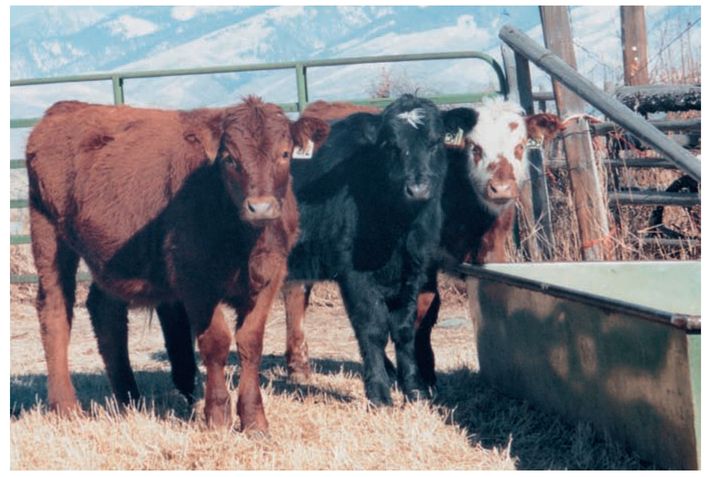

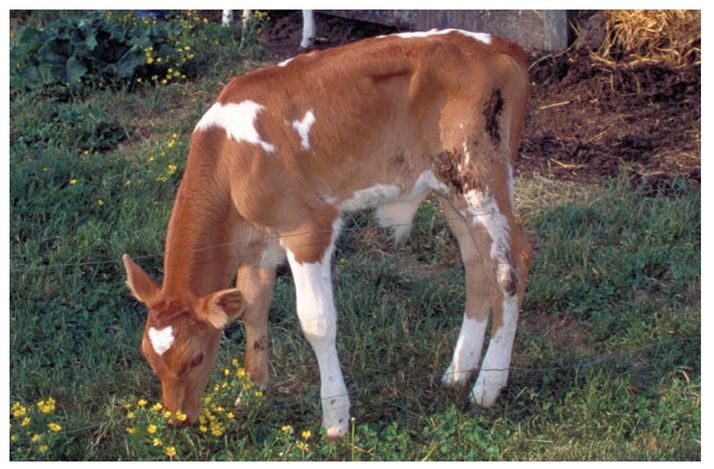

The telltale dried feces on this calf’s rump indicate coccidiosis. It’s common and curable but not something you want to bring home.

People who show cattle generally prefer longer legs, while producers who rely heavily on grazing often prefer short-legged animals.

HEALTH

Look closely for any signs of illness or discomfort. Eyes should be clear, not mattered (crusted) or inflamed.

In summer, coats should be smooth and shiny (except for longcoated breeds, such as Scottish Highland). A dull, flat-looking coat generally means internal parasites or poor nutrition. In late fall, winter, and spring, the coat should be uniform and thick. Bare spots could mean ringworm; although rarely a huge problem, it is a chore to treat.

Pay special attention to hooves and legs, checking for growths or swelling, especially at the top of the hooves and at the joints. There should be no swelling on the jaw, neck, shoulders, or brisket.

An occasional cough in adult cattle usually isn’t anything to worry about (cows do get colds and runny noses), but constant coughing signals problems. I’d hesitate before bringing any coughing animal home to my herd. In young calves, constant coughing or labored breathing may indicate pneumonia, a dangerous condition.

Check the hind ends of calves to make sure they aren’t matted with manure. Manure that is more water than feces is typical of scours, another common and dangerous affliction of young calves.

Polled cattle are naturally hornless, but if you’re buying a horned breed that has been dehorned, make sure the spot is well healed and not sprouting any more horn.

HOW CATTLE ARE PRICED AND SOLD

The pricing and availability of cattle generally follow a yearly cycle, which varies by the age and sex of the animals. Calves and steers are usually sold by weight, while heifers and cows for breeding are sold either by weight or by what the market will bear.

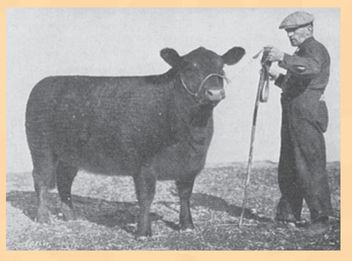

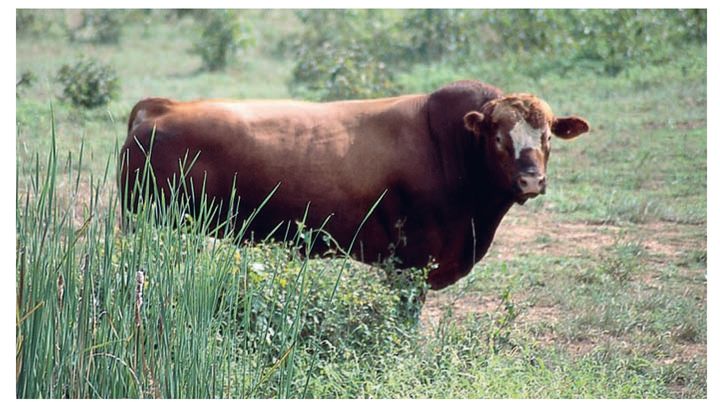

Bulls are normally priced according to their quality or what the owner thinks he or she can get. Bulls are most expensive in the spring and early summer, when they’re in high demand for the breeding season, and cheaper in the fall.

Bulls are the most expensive category of cattle to buy, and they will have a huge effect on the quality of your herd. Choose carefully!

Feeder calves—those that have been weaned and are ready to go on pasture or on a finishing ration—are usually least expensive in late fall, when the market is flooded with calves born the previous spring that are being sold before winter. Stockers or backgrounders (feeder calves headed for a few months on pasture before going on a finishing ration) are expensive in the spring, when landowners are buying cattle to keep their pastures grazed during the growing season.

Open, or unbred, heifers will be most expensive in spring, just before breeding season; the price tapers off through fall, when they’re cheap because it’s not economical to winter an open heifer. In addition, a heifer that didn’t “settle,” or get bred, during the summer may be infertile and good only for being finished and slaughtered. Bred cows will be most expensive in the spring, just before calving, and cheaper in the fall, when you will have to feed them through the winter. Before buying a bred cow, always have a veterinarian check to see whether she is really pregnant.

Cattle prices are listed, usually weekly, in local and state farm papers. If you have a farm radio station in your area, prices are typically announced daily or weekly, and some state extension services list current cattle prices on their Web sites. Cattle prices are listed either as dollar and cents per pound or as dollars and cents per hundredweight. If, for example, I were looking for feeder calves, I would look down the column until I came to that category under the listing for the auction barn closest to my farm, and then I’d start with the midrange, 400- to 600-pound category. If steer feeder calves were listed at $1.00, then the price for a 500-pound feeder steer would be $500. Keeping track of prices gives you a good idea of what you should be paying when you buy, but keep in mind that it may be worthwhile to pay a little extra for cattle you know are healthy, have been vaccinated, and come from good parents.

Body Condition

Body condition scoring (BCS) is a simple method for assessing how fat or thin cattle are, which will help when you’re looking at cattle to buy or assessing the cattle you already have. It’s kind of like learning to play a guitar: Anyone can quickly figure out a few simple chords, but getting good at it takes some practice. So it is with body condition scoring: it’s a simple system and you can start using it right away, but getting exact results takes experience.

While dairy cattle owners mostly use a five-point scale for BCS, beef cattle owners use a nine-point scale (see right). Although specific criteria are used in BCS, it’s a fairly subjective measurement. The point of doing it is to assess whether the cattle are in the right condition to raise big calves, to make it through a cold winter, or to breed back easily. Cows that are too thin produce less milk, which results in smaller calves. Thin cows also need more feed in the winter, since they don’t have a lot of insulating fat to hold body heat and so have to work harder to stay warm. Cows that are too thin may also have trouble getting pregnant, while cattle that are too fat will bring a lower price at auction due to all the weight that’s essentially a waste product.

The optimum BCS for a cow is 5 to 7, or “pleasantly plump.” A cow’s body condition should be scored three to four months before calving, allowing time to adjust the ration and to let them gain or lose enough weight to be in optimum condition for calving and rebreeding.

To score cattle, look at the fat covering the ribs, shoulders, back, and tailhead. The numbers break down as follows:

1. Emaciated: no fat visible anywhere; ribs, hip bones, and backbone clearly visible through hide

2. Poor: spine doesn’t stick out quite so much

3. Thin: ribs visible; spine rounded rather than sharp

4. Borderline: individual ribs not obvious; some fat over ribs and hip bones

5. Moderate: generally good overall appearance; fat over the ribs and on either side of tailhead

6. High moderate: obvious fat over ribs and around tailhead

7. Good: quite plump; some fat bulges (pones) possibly visible

8. Unquestionably fat: large fat deposits over ribs and around tailhead; pones obvious

9. Extremely fat: tailhead and hips buried in fat; pones protruding

Jewel, our herd matriarch, is in the 8 to 9 BCS range and moves a little slower than the rest of the girls. Even though she’s really fat, she produces an excellent calf each spring and breeds back easily. I could separate her from the rest of the cows and put her on a diet, but since she’s happy and doing her job, I haven’t.

WHERE TO BUY CATTLE

Finding cattle for sale is a matter of checking ads in local newspapers or regional farm papers; looking at bulletin boards at the feed store, farm supply store, and rural gas stations; and just asking around. If there’s a beef producers association in your area, join it. If you don’t know whether there is one near you, give your extension agent a call and ask. An association is a great place to network and get some background information on area beef cattle operations and auction barns. County and state fairs are other good places to find beef producers with cattle for sale. Go to the cattle shows, walk through the barns, and visit with the exhibitors. Two additional sources for leads on cattle for sale are your local artificial insemination service and veterinarian.

Auction barns move a lot of cattle, but they’re no place for beginners to buy. If you go, take a friend who is a good judge of cattle and can help you avoid the ones that are sick, are wild, or have bad hooves and legs. You may want to make a few dry runs to the barn, going early to visit the pens and then watching the auction without buying, to give you a feel for how the bidding process works and how cattle are moved in and out of trailers, pens, and the auction ring.

A better idea is to buy cattle directly from a seed stock producer or a commercial producer. Seed stock producers raise purebred cattle for sale as breeding stock and are good sources of quality animals. Commercial producers generally have mixed herds of several breeds or crossbred cattle being raised for beef production instead of breeding stock. These won’t be registered purebreds, but often they’re of good quality and reasonably priced; sometimes they aren’t. Most commercial cow-calf operators sell their calves after weaning in the fall, and this can be an excellent opportunity to purchase.

This good-looking Charolais-Limousin cross calf glows with health as it waits its turn for showing at a county fair. Fairs can be excellent places to meet other cattle people and get leads on animals available for purchase.

Dairy bull calves are a common item at auction barns, but it’s better to buy directly from the farmer and save the calf the stress of being hauled twice to strange places and exposing him to who-knows-what bacteria and disease at the auction barn. When you buy directly from the farmer, you can make sure the calf is at least three days old and has received colostrum, his mother’s immunity-boosting first milk. This is critical to a calf’s health.

BRINGING CATTLE HOME

Once you’ve bought your cattle, you have to get them home. If you’re buying from a breeder, he or she may be willing to deliver the cattle for an extra fee. Otherwise, you’ll either have to hire a cattle hauler or do it yourself. There are usually haulers for hire in any area where there’s cattle, and you can track one down by asking neighbors or calling a local auction barn. If your only option, or the option you prefer, is to transport your new livestock yourself, you’ll have to buy, borrow, or rent a trailer (unless you’re buying small calves you can fit into a pickup or small truck).

When the cattle arrive at your farm, ideally you’ll turn them into a solidly fenced small pen or barnyard, with water available and some nice hay scattered around. Don’t rush them out of the trailer; give them time to look around and step down carefully. Of course, they may decide to all come out in a rush, but let that be their decision. Once they’ve had a few hours to get a drink, find the salt, and get a bellyful of hay, open the pasture gate. By then, they should be calm enough to walk, not run, out. They might start grazing immediately or go on a tour to figure out where the fences are.

If you’re using electric fencing and the cattle you’ve bought are familiar with it, you can turn them out with no worries. If they don’t know what an electric fence is, you’ll need to train them as outlined in the fence section of chapter two. Don’t try to train them as soon as they get off the truck, however. That’s a lot to ask of already-stressed animals and may send them over the fence and back toward their previous home. You can have the wire ready in the pen, but don’t turn it on until they’ve settled down.

You can also turn new cattle directly into the pasture. If you do this, plan on spending some time watching them to make sure they don’t charge and break fences or decide to hop over and head back where they came from. Make sure they find the water, salt, and mineral within twenty-four hours.

Calves in a Van

Our first beef cattle were dairy calves. To bring them home, we put a tarp down in the back of the van with some straw on top, and I had the kids sit with the calves and keep them lying down. They won’t make a mess if they’re lying down!

Two calves try to figure out a supplement feeder. Cattle are naturally curious, and if you keep them calm, they will quickly adapt to new surroundings and new routines.

Watch your new cattle particularly closely for the first two or three weeks. Are they grazing contentedly, bunched tightly, or spending a lot of time walking instead of chewing? If they’re walking all the time, you’ve got pasture that’s too poor, and you should give them some supplemental hay. If they’re bunched, you probably have a fly problem and should provide a shady area for them to get away from the worst of the flies. You may also need to put up some sort of rub—a rope or padded post impregnated with fly repellent—that will put the repellent on the cattle when they scratch themselves. Are the cattle spending plenty of time lying down and chewing their cud, or are they always standing up and acting nervous? If they aren’t lying down, something is bothering them, and you’ll need to figure out what it is and fix it. Once, we had a bear stroll through the back pasture, and the whole herd went through the fence! We moved the cattle to a paddock close to the house, where the dogs could keep the bears at a distance and the cattle could chew their cuds in peace.

Make sure, too, that your cattle are drinking enough water. In temperate, reasonably dry weather, they’ll come for a drink at least once, and usually twice, a day. If they’re not drinking and it’s not raining, there’s something wrong with your water setup. I remember one cold winter day when our cattle wouldn’t drink, and I found out why when I touched the water. It was carrying an electric charge from a shortedout heater!