CHAPTER FOUR

Feeding Beef Cattle

Agricultural colleges teach entire courses on cattle feeding and nutrition, but for the small-scale beef producer it doesn’t have to be that complicated. There are three basic components to the cattle diet on a small farm: pasture, hay, and grain. This chapter will help you determine which foods to feed at which times and under what circumstances, in the way that’s best suited to your cattle, your land, and your budget.

One important rule to remember is: whenever you change your cattle’s diet—whether when moving the cow herd from hay to pasture each spring or when moving steers on to a finishing ration—do it slowly. The naturally occurring bacteria in cattle digestive systems, which transform food into nutrients, need time to gear up for a new ration.

PASTURE

Being able to tell a good pasture from a bad one is easy once you know what to look for. Converting a bad pasture into a good one is also fairly simple, if you do a little planning and use fences to control where the cattle graze and for how long. The most critical ingredient in the recipe for developing and maintaining a high-quality pasture is, as the old saying goes, “the footsteps of the owner.” A daily stroll across the pasture will give you a feel for which plant species grow through the season, how your cattle graze, and where the rich spots and poor spots are. That knowledge is the basis of good pasture, and good pasture is the foundation of a healthy ecosystem on your farm and of healthy cattle. Many graziers record what they planted in each pasture and how many days cattle could graze there each season.

PASTURE QUALITY

The grasses and clovers that cattle like to eat grow differently from trees, shrubs, and some weeds. If you understand this difference, you’ll understand why mowing and grazing are the keys to good pastures. Grasses and clovers have a “growing point” at or near the ground. When a cow bites off a blade of grass or a clover stem, the plant quickly regrows from this growing point. Trees, shrubs, and weeds, however, grow from the tips of their branches and leaves. If a person with pruning shears or a cow nips off this type of plant, it takes a long time for it to regrow because it’s lost that special set of cells programmed to grow the plant. That’s why, when you prune a shrub, it stays pruned for months. By contrast, you have to mow the lawn every week—the cutting actually stimulates it to grow faster by removing the older leaves that are getting in the way of the growing point at the base of the plant. Grazing has the same effect on individual plants as mowing does, so grazing, when correctly managed, results in lush pastures.

Unmanaged grazing, however, can devastate a pasture. This is because when a mower or a cow shears off the leafy part of the plant it temporarily depletes the food supply to the roots, and some of those roots die. Dead roots put a lot of organic matter into the soil, which is great for holding water and keeping the soil moist, but a great many live, healthy roots are necessary for a thick, lush pasture. You want a balance between dead roots and live roots. If you cut your grass every day or let your cows graze the same plants every day, you kill too much of the root, and the grass will become stunted or even die. If the process goes on too long, the soil loses much of its plant cover and becomes vulnerable to air and water erosion.

Weeds are especially abundant with extensive or continuous grazing systems, in which the cattle feed in the same pasture for an entire growing season. Because the cows keep the grass and clover so short, the weeds have no real competition for sun or water and thus can grow with little restraint. In the spring, when all the plants in an extensive pasture get off to an even start and are growing like gangbusters, an extensive pasture looks great. By late summer, when the rain has slacked off, the spring growth spurt is over, and the cattle have kept their favorite plants short, a lot of these pastures are full of big weeds, tiny grass plants, and skinny cattle.

Did You Know?

Cows are not picky eaters. An amazing variety of feeds are used in commercial feedlot finishing rations, starting with grains ranging from corn, barley, oats, rye, and millet to an eclectic collection of additives derived from other crops and from food processing by-products. These range from beet pulp, wheat bran, molasses, and potatoes to cottonseed hulls, linseed meal, soybean meal, and brewery by-products. Latest on the feedstuffs scene is a by-product from corn-based ethanol production, which is cheap if you live near an ethanol plant but has a short shelf life when the weather is warm. Cattle’s willingness to eat such a wide variety of feeds is one of the main reasons they have adapted so well to so many different environments.

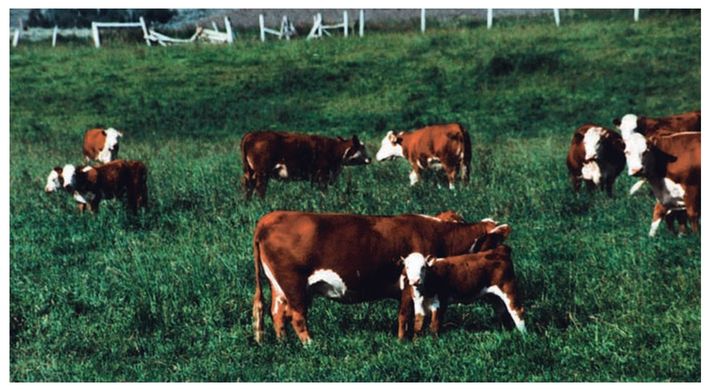

Green pasture on good soil provides all the nutrients beef cows need.

By contrast, grass that isn’t grazed while it’s still fairly young and tender gets stiff from hard-to-digest cellulose as it matures. The tall grass blades shade the growing point near the soil, and growth slows or stops. Some older plants in a pasture are OK; cows need fiber in their diet, just as we do, and older pasture supplies it. However, the older the plant is, the slower it grows, and the less palatable it is to cows. Keep in mind, too, that a certain amount of old growth left over the winter can protect roots and growing points from freezethaw cycles that heave the soil and break roots. Too much, though, and the ground will be shaded and slow to warm in the spring, and new growth will have a tough time struggling through the old stuff to reach sunlight.

In summary, a thick pasture full of grasses and legumes that cattle like (as discussed in chapter three) and lacking the weeds they dislike—with grass that isn’t too old or too short—is ideal for the health and growth of cattle. This type of pasture provides the added advantages of growing longer into dry spells, greening up sooner in the spring, and staying green longer in the fall, which means money in your pocket that you won’t have to spend on extra hay.

ROTATIONAL VERSUS EXTENSIVE GRAZING

When all of these factors are taken into account, it would seem clear that the best way to graze cattle is to mimic how you mow your lawn: let them graze an area thoroughly for a short period, then put them somewhere else while the area rests and regrows. This is called rotational or management intensive grazing. Since the science of it was worked out in the 1960s and 1970s by Allan Savory, founder of Holistic Management International, and a host of other researchers, farmers, and ranchers around the world—and portable fencing became readily available in the 1980s—rotational grazing has been quietly revolutionizing pasture and range management.

Yet extensive grazing is still by far the most common pasture system in the United States. It can work pretty well for a cow-calf operation. If you have a lot of land and just a few head of cattle, it may be the most economical choice. The cattle can be turned out for the grazing season and left largely on their own; you only need to make sure they have water, salt, and a mineral mix on hand at all times. If the pasture is big enough, no one will starve, although if it gets dry in the late summer and grass growth stalls, the cattle will need hay.

The biggest long-term problem with extensive grazing is that it can wreak havoc with the soil, water, and vegetation. Cattle that return to the same areas day after day to graze or rest will kill the plants and compact the soil. If there’s a stream or pond in the pasture, they’ll trample the banks into mud. With no lush vegetation to shade the water and no roots to hold the soil, the water temperature will rise and the banks erode, clouding the water and silting up the bottom. This is devastating for many aquatic species, especially prized ones such as rainbow trout. When cattle rest in the shade of the same trees day after day, the trampling can destroy the delicate feeder root systems and kill the trees. When palatable grass and clover plants are constantly grazed into the ground, noxious weeds can turn into major problems. Most of us have seen pastures that seem to consist mostly of thistles or spotted knapweed, where all remaining grass is kept grazed to the height of a golf course green. Especially in dry climates, where even without cattle it’s difficult for vegetation to prosper, extensive grazing can be devastating.

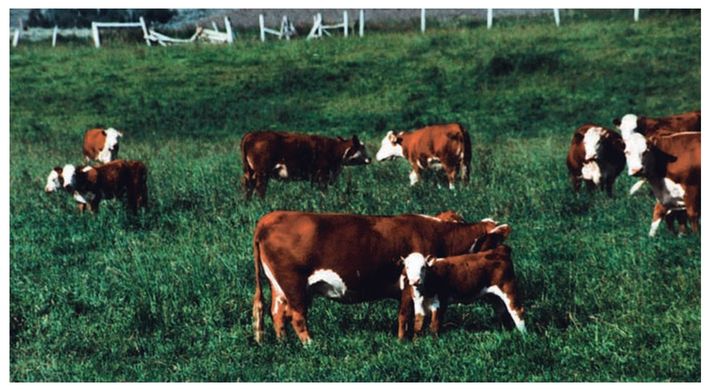

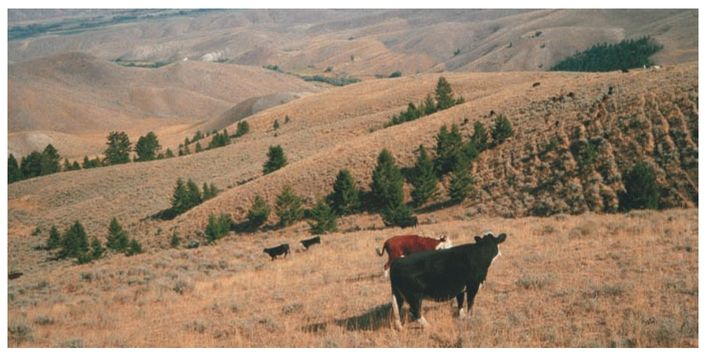

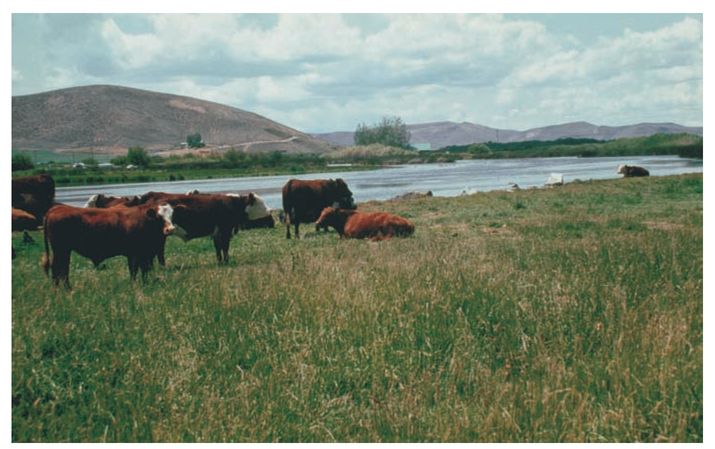

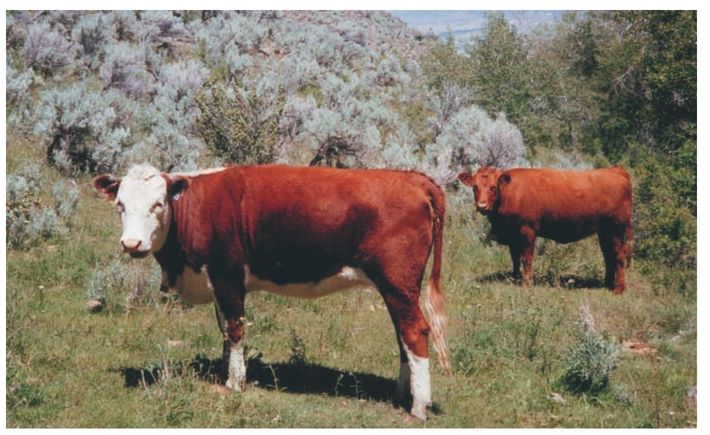

This range grass is still green and high in protein—ideal feed for these young cows. The greatest single factor in determining the quality of grass is its stage of maturity.

Cattle in a pond or stream look picturesque—but it’s hard on the water quality. Limit cattle access to natural waterways by fencing off a small drinking area, and leave the rest of the bank to recover its vegetation.

Setting up rotational grazing for beef cattle is fairly simple. Using whatever type of fence you prefer, split your pasture into several paddocks. Step-in posts and plastic electric wire are the cheapest, quickest, and most common choices for paddock fences. If, however, you don’t care for the constant maintenance required by electric fencing, you can put up permanent paddock divisions.

Paddocks should be sized to provide enough pasture to feed the herd for at least three days but usually no longer than a week. A shorter period tends to make beef cows too fat, and a longer stretch allows them to regraze plants that are just beginning to regrow. If you’re grazing steers with the goal of putting on as much weight as quickly as possible, you can shorten the rotation time to twenty-four, or even twelve, hours, although it’s not necessary if the pasture is in good condition.

Paddocks need to be rested anywhere from a couple weeks during the spring flush of growth in high rainfall areas to several months in hot, dry regions. Getting it all right takes some experimentation, talking to other rotational grazers in your area, and practice. Fortunately, rotational grazing is a forgiving process, and the cattle will probably do fine while you fine-tune your system.

Keep offering hay in the spring until grass growth can keep up with grazing. The cattle will let you know when they don’t need hay—they’ll quit eating it.

Portable fencing makes it possible to change paddock sizes and configurations at the drop of a hat. In those years when I have more cows, I subdivide the land into more paddocks and graze them for shorter periods. When I have fewer cows, I cut back on paddock numbers and don’t graze as tightly. Some years, I mess up or the rains just don’t cooperate, and I have to feed hay in August. Most years, I also graze all or part of our hayfields, either early in the spring or late in the fall or during a dry stretch when the pastures have given out. Anytime a cow can harvest forage for herself, rather than your having to do it mechanically, will save you time and money.

Overall, rotationally grazing pastures produces significantly more grass as well as more palatable grass than extensive grazing does. In practical terms, that means faster-growing animals and fewer out-of-pocket costs for feed. Organic matter in the soil increases, which helps hold moisture in. Consequently, grass growth continues longer into a dry spell. The pasture gets thicker and lusher. Trees are hardier and quit dying from soil compaction. The tall grass along streams shades the water, keeping the temperature at a more optimal level. The roots hold the soil of the stream banks tightly—preventing the stream from eating away the banks, depositing dirt on the stream bottom, and widening the stream and making it shallower. As a result, the stream stays narrow and deep, and the water is clear.

GRAZING MANAGEMENT BASICS

Some grazing management practices are dependent upon climate. In arid areas, according to Allan Savory, a high density of grazing cattle is necessary to break up the soil crust and to work seed as well as fertilizing manure and urine into the ground. In the Deep South, where high summer temperatures prohibit grass growth, some cattle owners plant warm-season annual forages for grazing when pastures aren’t producing. In our area, the Midwest, the major concern is weed control. I mow paddocks once or twice a season, just after they’ve been grazed. In general, it takes grasses and clovers about three days to begin regrowing after they’ve been grazed. You want to mow within that time window so you’re only mowing plants the cattle didn’t graze, not cutting regrowth. In the areas where the ground is too rocky or steep to mow, I hand-cut weeds, preferably before they go to seed. Because we’re a small operation and I like being out in the pasture in the evenings, I find this to be a pleasant chore.

Every two or three years, it’s a good idea to test your pasture soil. This involves taking a small shovel and a bucket and gathering samples from the top few inches of soil at several locations in the pasture. Mix up the samples, put some in a plastic bag, and send them to the soil testing laboratory. In a few weeks, you’ll get back a report showing nutrient levels for nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus, as well as the pH level (acid-alkaline). When you submit your samples, ask the lab to test for trace minerals, too, especially calcium. If your pasture is deficient in any nutrients or minerals, you’ll need to purchase and spread the correct amendments or hire someone to do it for you. To find a soil lab in your area, to get precise directions on how to take a sample, or to locate lime and fertilizer dealers, start by asking your local agricultural extension agent or the feed and seed dealer. Ask what time of year is best for taking samples and spreading amendments in your area, too, because this makes a difference in the accuracy of the test and in maximizing the benefit from anything you add to the soil.

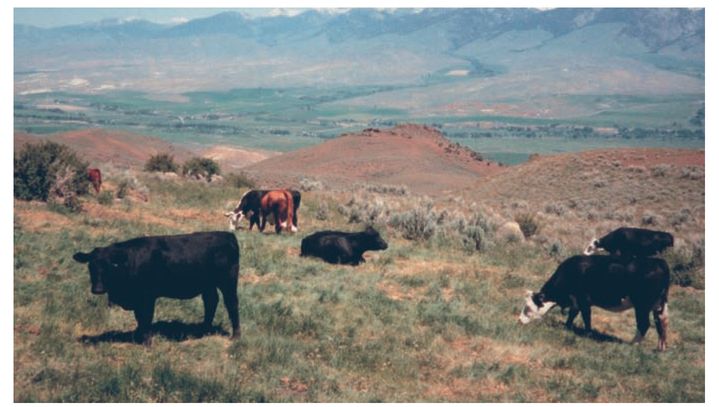

Cattle can make good use of western land that is too steep and dry to farm. When the grazing is well managed, cattle can help restore and maintain the land’s healthy state.

Finally, pastures should not be monocultures (limited to one plant type). You don’t want to eat the same thing for every meal, and neither do your cattle. A mix of several types of grasses, a few different legumes, and an eclectic selection of other plants, such as dandelions and plantains, will furnish a nicely balanced diet for cattle. Most pastures are already very diverse, but if you’re short on one of those plant categories, you can buy the seed and work it into the pasture. How you work the seed into the soil and at which time of year depends on the type of seed and the condition of your pasture as well as where you live. Ask your seed dealer, extension agent, and any other specialist you can find for advice, then use what seems to fit your situation.

HAY

As mentioned in chapter two, beef cows are at the bottom of the list when it comes to needing top-quality hay. As long as the hay isn’t moldy or nothing but stems with no leaves, it’ll do for beef cows. Pure, high-quality alfalfa hay, which is high in milk-producing protein and low in body heat–producing carbohydrates, can be harder on beef cows than old, coarse hay. You might want to use it if you’re fattening steers during the winter. Knowing when to buy or harvest hay saves you money, and planning your winter feeding to fit your equipment and schedule can save a lot of time and labor.

Did You Know?

In his Farm Book, compiled from 1774 to 1826, Thomas Jefferson reports, “In fattening cattle they will eat from ⅓ to ¼ of their weight in turnips per day besides hay. They will fatten in four months on turnips and hay alone, or in three months on a change of food. They prefer carrots to turnips. Lots of them will suffice and fatten faster.”

WHEN TO BUY OR HARVEST

If you’re buying hay for cows and calves, you don’t need the expensive stuff. During the growing season, keep a close eye on the weather in your region. Dry seasons quickly create hay shortages, driving prices sky high. Buying early and in quantity during good years and storing the excess is generally your best bet. In covered storage, hay will last for years, and even round bales stored outside will last two or three years if the bales are tight and kept on dry ground. Don’t pay for any hay until you’ve dug into a few bales and checked for mold, weeds, and stem content.

If you’re having hay made for you on your land or making it yourself, don’t be in too much of a hurry. Waiting a little longer into the season to make your first cutting of hay gives you several advantages: The hay will be taller, giving you more volume. It will be higher in carbohydrates and lower in protein, which is good for keeping cattle warm in the winter. The weather in most areas will be more settled, with less likelihood of a surprise rainstorm ruining the cutting. Grassland nesting birds will have a better chance of getting their babies fledged and out of the nest before the hay mower comes through. In addition, if you’re depending on someone else to make your hay, he’ll likely be less busy later in the season. Here in northern Wisconsin, our dairy farming neighbors like to have their first hay cutting done by late May or early June. I generally wait until late June to cut ours. If I want to slow it down even more, I can graze the cattle on the hayfields in early spring to set the crop back a week or two.

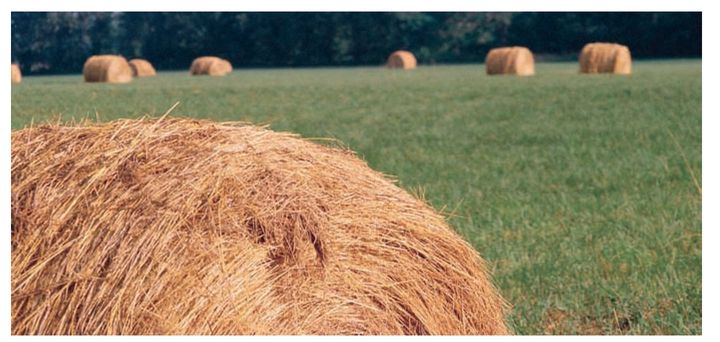

Large round bales are widely available and, if you have the handling equipment, are an economical and easy way to feed your herd.

Our local dairy farmers also like to take three or four cuttings off their hayfields each year. I take two—I’d rather have the cows harvest it by grazing a couple times than have to haul out the tractor and Haybine again. This extends the grazing season and cuts my out-of-pocket feed costs. As an added benefit, the cattle fertilize as they graze.

WINTER HAY FEEDING

How you winter feed your cattle depends on your setup and preferences. If you have just a few head of cattle and are using small square bales, it’s easy to construct a wooden hay feeder or buy a metal feed bunker. If you’re feeding round bales, you’ll need round bale feeders sized for the bales you have. These are widely available at farm stores, and the pieces can be hauled in a small trailer for assembly at home. Some local stores might even deliver.

If you’ve got a shed for the cattle, you can feed hay inside. This is nice in foul weather, but it greatly increases the volume of manure you’ll have to clean up next spring because cattle like to stick close to the hay in winter. If you feed outside, you can either feed in the same spot every day or keep moving the hay feeder to a new location.

If you’re feeding in the same location every day, the happiest situation is having the hay feeders on a cement pad. This eliminates the mud and simplifies cleanup in the spring. If you don’t have a cement pad, your dirt feeding area will become a “sacrifice area,” so churned up by the cattle that it’s unlikely you’ll have anything growing there for a long time. Put a sacrifice area where it won’t destroy the view from the kitchen window. In either case, plan on scraping the feeding area or the shed clean in the spring and spreading the moist mix of manure and old hay on your pasture or hayfields with a manure spreader. This typically requires a Bobcat with a bucket, a tractor, and a manure spreader. In some areas, custom operators will come in and do the job for you, or you can borrow or buy your own equipment. If you don’t clean up the area, chances are that in most areas of the country you’ll have a terrific infestation of stable flies, as the manure-hay mixture is optimal for their breeding. Stable flies will keep cattle running around the pasture to get away from their ferocious bites or miserably bunched in a corner instead of grazing.

These round bales were placed and fenced off on a poor area of pasture before the snow flew. As the round bale feeders are moved back week by week through the winter, the cattle leave a layer of mixed hay and manure on the ground—a superb fertilizer that will reinvigorate the pasture without my having to do any manure spreading.

The other option for winter hay feeding is “outwintering,” or feeding hay on pasture away from the barn. The feeders are moved each time they’re emptied. The manure and wasted hay is spread as the cattle are feeding, and there’s no spring cleanup, except perhaps for running a harrow or disk over the area to break up the big clots and spread it a little more evenly. Be aware, however, that in areas where winters are wet and the ground doesn’t freeze this system will quickly make a huge muddy mess in pastures. Where the ground freezes, it’s a terrific way to renovate poor spots in pastures. Because it’s frozen, the sod won’t be badly cut up by the cattle, and in the spring, the ground will be covered with a layer of manure mixed with hay, the best fertilizer there is. The cattle won’t graze the area until late in the following growing season, but the pasture there will be lush and deep green for years to come.

Advice from the Farm

Feed for Cattle

Here are a few words from our experts on feeding your cattle.

Wintering

“We have no barn. The round bales are stored outside. The cattle are wintered in a half-wooded horseshoe ‘coulee’ of about forty acres, with a year-round spring. We feed the round bales right on the ground, and the cows clean it up pretty good. What little they do not eat is their bedding. No sense in having the cows eat all the hay and then haul in straw to a barn just to have a damp place where the sun doesn’t shine and disease builds up.”

—Mike Hanley

Going Light on the Grain

“I probably have them on a finishing ration four to seven months, because I don’t feed a lot of grain. I put them in a little early, and I don’t feed them really heavily, maybe fifteen to twenty pounds of a mix of corn and barley. The rest is silage and hay. I think you get a better meat and fewer health problems.”

—Donna Foster

Doing It by the Pail

“For finishing at home, doing it by the pail method—buying your corn and oats and protein supplement and mixing it yourself—saves the extra expense of having the mill mix it. There’s a lot of supplements out there, and you have to get one you’re willing to work with. A lot contain antibiotics and stuff, and we don’t use those.”

—Rudy Erickson

Putting Up Very Good Feed

“Consider putting up oat hay, sweet clover, sorghum-sudan hybrid mixes, forages mixed with grains, and soybean hay. All these are things I’ve seen put up in my lifetime, and with the new equipment today it can be done a lot easier than in the old days. Any of these fed properly to livestock is very good feed.”

—Dave Nesja

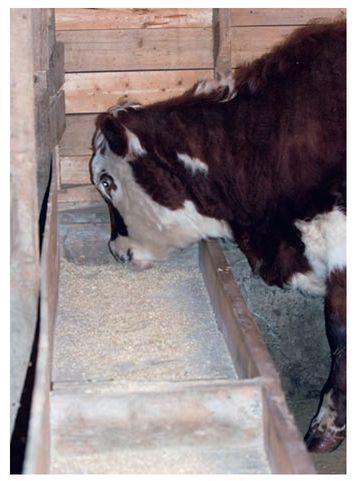

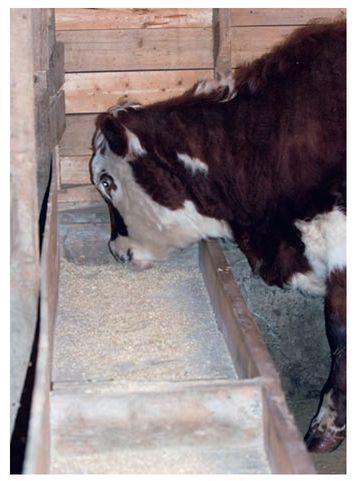

This yearling steer was started on grain before weaning last fall and now in the spring comes eagerly for his daily ration inside a converted pigsty. Starting grain feeding early teaches cattle to come when called and is an easy way to fatten a homegrown steer for market.

With outwintering, you can either haul hay out to the feeders a few times a week, or you can set all your bales out during the fall and not have to start a tractor all winter. This is what I and quite a few other beef and dairy producers do in our area: In October, I calculate how many bales I think I’ll need for the number of cattle I’m carrying through the winter and for the length of time I think the ground will be frozen. With a tractor and hayfork, I set out the round bales in three or four rows, spaced fifteen to twenty feet apart on all sides. When the bales are in place, I cut and pull off all the twine (or netting wrap) by hand. I build a three-strand electric fence around three sides of the rows, leaving one side open. I roll the round-bale feeders out of storage and pop them over the bales at the head of the rows on the side that I left open. Then I stick plastic step-in posts into the next row of bales and run two strands of electric wire across them to keep the cows from the rest of the hay.

Constructing this “hay corral” takes me twenty to thirty hours, but it’s pleasant work in moderate weather and it means I won’t have to start the tractor on cold mornings or fight with twines or round bales frozen to the ground. Instead, once or twice a week I unplug the electric fence, walk out to the hay corral, move the portable electric wire back one row, tip the feeders on their sides, roll them over to the new row of bales, then walk back and plug in the fence again. This takes all of fifteen minutes. What’s left of the old bales is bedding for the cows, keeping them clean and out of the snow. In the spring, what was a poor area of pasture will be fertilized, and by late summer, the pasture will be deep green and growing taller and lusher than anywhere else.

GRAIN

Cattle love grain, and that’s a good thing because it brings them running when we want them and can produce tender, tasty beef from even mediocre animals. Although the most common grain fed to cattle is field corn, they will eat a wide variety of other offerings, from oats and wheat middlings to soybean meal and cottonseed meal. For the small operator, corn is usually the cheapest, most available, and easiest grain to buy in small quantities (under a ton). Corn should be ground or rolled so the cattle can digest it better.

Feed Additives and Growth Supplements

More than 90 percent of cattle being fattened for slaughter are implanted with hormones and given antibiotics in their feed to make them grow more quickly and to convert feed to muscle more efficiently. When done correctly, the economics of these practices are persuasive. Properly used hormone implants will add forty to fifty pounds of weight to a finished steer for a couple bucks’ investment, while antibiotics and ionophores (a particular class of antibiotics with a different mode of chemical action in the body) increase the efficiency of digestion by 10 to 20 percent, which results in quicker weight gain. Antibiotics in the feed at low levels also help prevent illness and disease in what is (in a feedlot) a very crowded and dirty environment for cattle, which are being fed an unnatural diet.

Hormone implants are placed in the middle third of the ear and are either a synthetic estrogen that will increase muscle gain, a synthetic androgen that decreases protein breakdown and so increases muscle mass, or a combination of the two. A wide variety of dosages and mixes is available so a feedlot manager can gear an implant program precisely to the type and age of cattle being fattened. However, implants inserted incorrectly or the wrong implant type for the animal can diminish the benefit. An estimated 25 percent of implants have abscesses around the implant site, reducing their effectiveness, and implants in larger breeds can result in animals so large that processors will discount the price. Implants can also increase toughness and delay marbling—the fat deposited inside the muscle—and so lengthen the time the animal must be on feed to reach a higher quality grade.

Concern over the effects of these practices on the environment and humans has grown markedly in the past few years. An article by Michael Pollan in the March 31, 2002, edition of the New York Times Sunday Magazine, titled “This Steer’s Life,” probably did more than any other single event to galvanize public interest in what had been fed to the beef they were eating. Mr. Pollan revealed that most antibiotics sold in the United States end up in animal feed, not in people, and thereby add considerable impetus to the ominous and accelerating development of antibiotic-resistant human infectious agents. The synthetic hormones that are slowly released into cattle bloodstreams through implants leave measurable residues in both the meat and the manure. Manure that gets washed into nearby streams and lakes, in turn, leaves measurable levels of hormones in the water, where fish with abnormal sexual characteristics have been found. Some scientists believe, Mr. Pollan wrote, that this build-up of hormonal compounds in the environment may be connected to falling sperm counts in human males and premature maturity in human females.

These yearling steers on excellent pasture will fatten easily without a lot of grain.

Talk to your feed store about other feed options in your area or additional additives, especially if you are fattening a steer for slaughter. Corn alone isn’t high enough in protein to satisfactorily fatten an animal during a short period. Corn and good pasture will do the job, but if you don’t have lush pasture or high-quality legume hay during the finishing period, you should talk to your feed dealer about formulating a finishing ration. In addition, in some regions there are cheaper alternatives to corn, making it worth your while to inquire.

Beef cows whose purpose is to produce calves, not meat, don’t need grain if they’re on good pasture in summer and adequate hay in the winter. But I give them a little anyway, as do most beef producers I know. It’s called “training grain.” A small amount—a pound or less for each cow—brings them running every morning when I call. Because our bunker feeder is inside the holding pen, getting them in when I need to work with them is never a problem. As a bonus, the cows teach their new calves about grain each year so when it’s time to start the calves on grain, they know exactly what to do.

You should start calves on grain no later than when you wean them. If you want to start them before weaning, set up a “creep feeder” that will keep the cows out of the calves’ grain. A creep feeder is a pen or shed with an opening too narrow for cows but wide enough for calves. Inside is a bunker feeder for the calves. I generally put a board over the opening as well to make it too low for a cow to squeeze under. If you have an old shed not being used for anything else, it might work well for a creep feeder. We use an old pigsty.

Until you put weaned calves on a finishing ration, grain isn’t essential to their diets, but it will help them grow a little faster. Many cattle owners “rough” calves through the winter on hay alone and don’t start them on grain until four months or so before slaughter. But feeding weaned calves a pound or two of grain per head per day will quickly teach them to come when called, help them grow, and keep them tame.

FEEDING DAIRY CALVES

Dairy bull calves need a lot of extra care and special feeding for the first few months. While a beef calf gets as much of his mother’s milk and affection as he wants for the first six months or more of life, a dairy calf loses his mother and his mother’s milk within three days of birth. So be kind to these babies, even though they’re often incredibly stubborn. They’ll be a little lost and stressed and vulnerable to infection and sickness.

If you buy dairy calves, pick up a sack of milk replacer for each calf from the feed store and a two-quart calf bottle and nipple (per calf) from the farm supply store. Follow the directions on the sack for how often to feed and at what temperature. To mix the milk replacer, fill the bottle half full of warm water, add the right amount of milk replacer, shake well, and add the rest of the water.

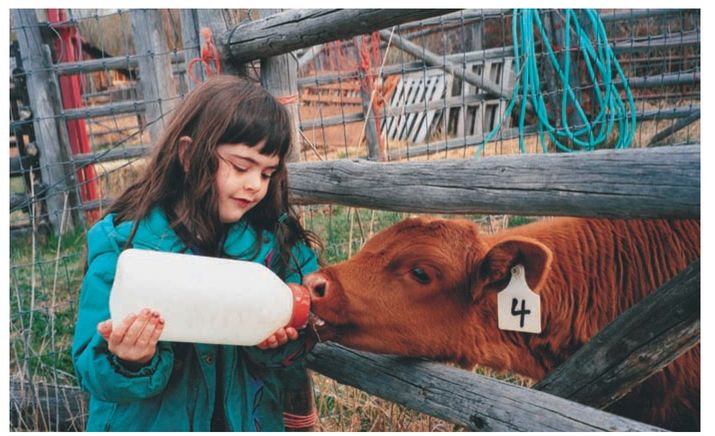

A girl bottle feeds one of the farm’s calves. Bottle feeding, which is necessary when calves have been taken from their mothers at a very young age, is fun for kids.

At first, it may take a little persuading to get the calf to drink from the bottle. If he won’t take the nipple, try backing him into a corner, then straddling him with your legs. Pull his head up and hold it with one hand, stick the nipple in his mouth with the other, and squeeze a little milk onto his tongue. Calves usually catch on pretty quickly. To prevent choking, don’t hold the bottle any higher than the height of the calf’s shoulder. Calves drink amazingly fast, and the milk will be gone long before their sucking instinct is satisfied.

Calves will try to suck on each other, which isn’t a great idea, but they seem to do it anyway. Distract them with calf feed. This is a sweetened grain mix that should be fed free-choice (available at all times) from the time they’re a few days old. Take some in your hand and stick it in their mouths after each bottle feeding until they figure out how to eat it themselves. Feed it in a bucket or box attached to the side of their pen, placed high enough that they won’t poop in it too often. In case you can’t get them outside in a small area with some green grass to nibble once they’re a few days old, keep some high-quality hay available for them. They won’t do more than play with it for a few days, but they need to get used to it now, while they’re still young and open minded about trying new things. It helps their digestive systems mature.

One sack of milk replacer and one to two sacks of calf feed will raise a dairy calf until weaning at eight weeks of age or older. Grain feeding should continue according to the directions on the sack of calf feed, with a gradual transition to an adult ration as the calf’s digestive system matures. Get a calf outside and on pasture as early as possible. You can buy calves in winter, but they’re even more susceptible then to pneumonia and scours (diarrhea) so make sure to provide them with a draft-free, deeply bedded pen, and keep it clean. It’s also a good idea to give them a good grooming with a cattle brush every day. This mimics the cow’s licking and is stimulating and comforting for the calf. A happy calf is more likely to be a healthy calf.

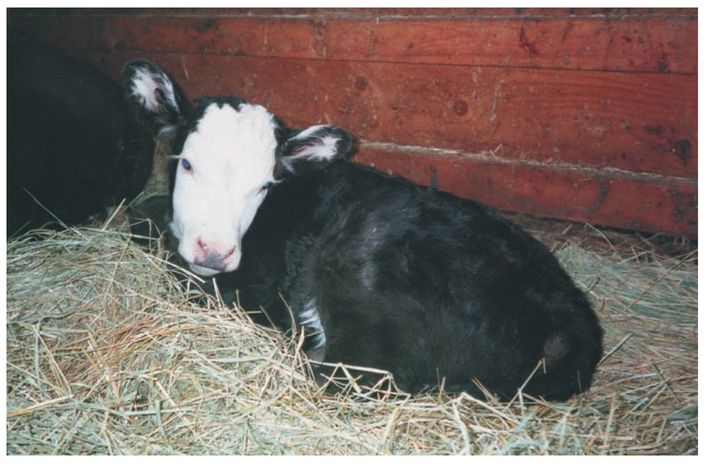

A clean dry place to lie down is the first step toward keeping a calf healthy, whether it’s a dairy or a beef calf.

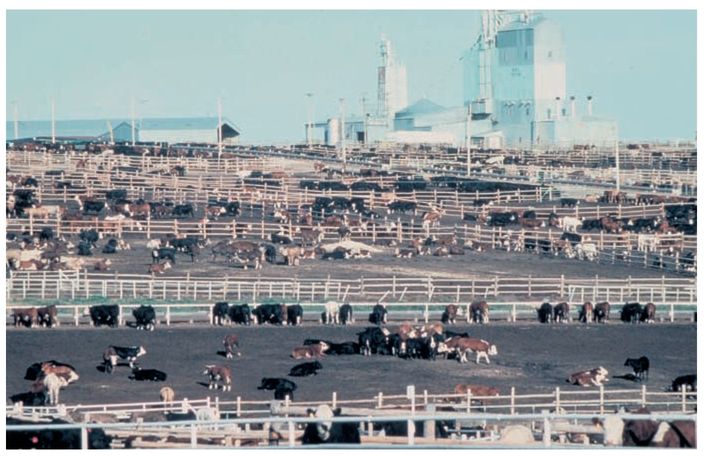

Most beef cattle are finished in large commercial feedlots such as this one, where they are kept in open-air pens and fed a ration precisely formulated for maximum weight gain.

FINISHING RATIONS

There are two approaches to fattening a steer for your freezer. The first is to use time and low-cost inputs, and the second is to speed up the process with a formulated ration fed at a high rate. The first approach usually makes the most sense for small farms because it doesn’t require an expensive ration or a separate pen. If you don’t have any land for grazing, it’s possible to put a weaned calf directly onto a finishing ration, provided it’s the right breed and a fastgrowing animal. However, the animal will still need plenty of forage-based fiber in its diet. Most calves need some time to mature before they will fatten and are better off on pasture or hay until they’re at least a year old.

You also have some choice as to when you send an animal to the processing plant. You can have “baby beef” from a steer as young as a year, although steers are normally kept until they’re more mature and have put on some exterior fat. A steer from one of the English breeds can be ready for slaughter as young as sixteen months, while a steer from a continental breed may not finish until it’s two years old or more, depending to a large extent on how much grain you feed. In a commercial feedlot, steers are kept in pens and fed as much finishing ration as they will eat. On a small farm, it’s usually more practical to keep the steers on pasture and feed them grain once or twice a day. If the pasture is excellent, four or five pounds of corn (usually with a protein supplement) each day will have most steers ready for slaughter in three to four months. Generally, it’s a good idea to finish a steer before the age of twenty months to ensure a tender carcass. Please remember, however, that these are just rules of thumb; they are not hard and fast formulas. Finishing cattle is not an exact science.

Reasons for Grass-Finishing Cattle

Farmers have three reasons for grass-finishing their cattle. Cost: grass is decidedly cheaper than grain, which is usually used for finishing. Health benefits for humans and cattle: There’s a body of research showing that grass-fed beef contains high levels of conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs), which appear to help prevent cancer in humans. In addition, a grass-fed steer’s digestive system won’t support the killer H151 E. coli bacterium; grainfinished cattle lack the CLAs and can harbor E. coli due to a lower-acid stomach environment. Environmental advantages: Grass-fed beef don’t occupy feedlots, which, by nature, have a high concentration of manure that pollutes the air (dust), water (runoff), and soil (too much manure creates nutrient levels that cross the boundary from being fertilizer to being pollution).

If the steer is on good pasture, it’s helpful if you can time the finishing so that it coincides with the end of the grazing season. Cattle gain weight faster and more cheaply on good pasture than on hay. If the steer is out with a cow herd, he can be trained to come to a separate pen for his ration. To do this, watch where the steer normally is when the herd comes in for the morning drink or grain ration. If he’s at the front of the line, close the gate behind him and move him forward into another pen. If he’s at the back of the line, close the gate behind the cows and feed the steer with a low bucket in the pasture. If he’s in the middle, you’ll have to finesse getting the cows ahead and keeping the steer behind for a few days until he figures out to stay behind for his ration.

Unfortunately, most of us can’t just walk up to a steer, jam a thumb in his back fat, and know that’s he’s ready. Two beef-raising friends, Barry and Libby Quinn, told me that you just have to develop an eye for finish. Former extension agent, current friend, and lifelong beef producer Dan Riley told us that a steer is ready for slaughter when you can see the fat around his cod, over his pinbones, and on the rear flank. If a steer has fat around the tailhead, he’s close to grading prime; if he has a fat brisket, he’s too fat.

GRASS-FINISHING

Cattle can be finished on grass, but it takes expertise to turn out high-quality beef without grain. If you are interested in grass-finishing, you first will need to buy the right cattle. Short-legged animals from the English breeds are probably your best bet. Second, you will need superb pasture, lush and high enough in protein that it will enable a steer to gain no fewer than 1.7 pounds per day for the last ninety days before slaughter. In most areas, this takes a combination of pastures and planted annual forages plus experienced management. However, any cattle can be raised to maturity on grass and slaughtered for edible beef. The meat may be tough and a little gamy tasting, similar to lean venison, but it will feed you. (See “Reasons for Grass-Finishing Cattle.”)

WATER

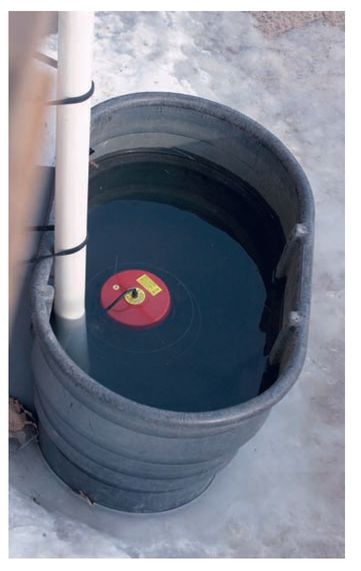

Clean water should be available at all times for your cattle. If the water isn’t fresh, they may not drink as much as they should. Tip the water tank a couple of times a season and scrub out the algae. A float-valve, available at farm supply stores, will keep the tank full when you’re not around. In belowfreezing weather, install a tank heater, also available at farm supply stores, and plan on being there to fill the tank daily because a float-valve freezes up in cold weather.

Unless you run a hose out to the paddocks, your cattle will need to come into the barnyard for a drink. When building your paddocks, create lanes giving your cattle easy access to the barnyard. These can be built with the same portable fencing used for the paddocks and should be about ten feet wide. Gates can be made by tying a gate handle onto the wire and adding a loop at the far gatepost to hook the handle through.

The health benefits of grass-finished beef are attracting a lot of consumer interest, but producing good beef on grass alone takes the right breed of cattle and superb management.

A rancher breaks up the ice in the cattle’s water trough in the dead of winter. In freezing weather, this may be a regular chore unless you have a water setup with a tank heater.

It’s not necessary to have water available in the pasture. Cattle will walk a long way to get water, and that’s usually good for them and their hooves. Cattle need regular exercise to stay healthy just as much as people do, and like people, they can be a little lazy about it. Even when you’re outwintering and there’s snow on the ground, cattle will plow through it to get to water and their grain ration. Some producers still rely on snow to water their cattle in the winter, but it’s difficult for them to get enough to stay fully hydrated. Eating snow also chills them, and they’ll lose weight burning calories to stay warm.

SALT AND MINERALS

Salt is essential to cattle, and the best way to make sure they get enough is to provide free-choice, loose salt in a feeder protected from rain and snow. Buy or build a two-compartment feeder, and put salt in one side and a mineral mix geared for your area in the other side.

Mineral deficiencies were a common cause of disease in cattle in the past. The diseases varied from region to region, depending on what was deficient in the soils. That’s why it’s important to get a mix formulated for your area of the country. As with salt, it’s easier for cattle to get enough minerals when the mix is loose rather than in a block.

A simple tank heater from the farm store keeps water available in winter for our cattle. I run the cord through a piece of PVC pipe in order to prevent the calves from yanking the heater out of the tank.

For steers being finished for slaughter, getting enough minerals and vitamins into their feed is especially important. These can be mixed in the finishing ration according to your feed dealer’s directions or fed free-choice in a separate feeder as you would normally do with the cow herd. If fed free-choice, the vitamin and mineral mix should be freshened at least once a week.