CHAPTER FIVE

Handling Beef Cattle

Large cattle operations have always known that handling cattle effectively on a regular basis requires a properly equipped facility, one that includes pens, a crowding tub, an alley, and a chute with a headgate (as discussed in chapter two). Even a small operation with a handful of cattle can build a scaled-down version of a good facility for a reasonable cost, and the right handling methods can make a barebones facility work smoothly.

Over the past several decades, there’s been significant rethinking of traditional cattle-handling methods, thanks to the work of such pioneers as University of Colorado professor Temple Grandin and cattle handling and marketing consultant Bud Williams, as well as many others. Their work has focused on understanding the natural instincts and behaviors of cattle and using that knowledge to design systems and handling methods that keep cattle calm and tractable. Temple Grandin’s cattle-handling layouts and techniques have been adopted by many major U.S. processing facilities and innumerable small farms and ranches. Bud Williams’s herding methods have set the gold standard for moving and holding cattle in the open, particularly in rangeland grazing.

CATTLE HANDLING FUNDAMENTALS

The most important concepts to understand when handling cattle are flight zone and pressure points. Flight zone refers to an imaginary circle around the animal that, when you cross it, causes the animal to move away. By working on the edge of an animal’s flight zone, you can gently move it in the direction you want. Because the flight zone varies by the tameness of the herd in general and by each individual animal, and can even be affected by weather conditions, it takes a little finessing to find it. Approach slowly until the cattle begin to move away from you. That’s the edge of the flight zone. Go farther, and they’ll move faster. Back off, and they’ll stop.

Pressure points are specific spots along the edge of the flight zone where, if you stand, you can turn cattle in a different direction. The most important pressure point is at the shoulder. If you’re in front of the shoulder on the edge of the flight zone, the cow will turn back. If you’re behind it, she’ll move ahead. If you’re to the side and slightly behind the rear of the animal—a second pressure point—she’ll move ahead. If you’re directly behind her, where she can’t see you, she’ll turn around to look at you. If you take a very visible stick along, such as a white step-in fence post or something with a small flag on the end, and you hold it out to the side, you’ll look three times as wide to the cattle and they’ll turn even more easily.

This is critical information to understand and use when you’re trying to move cattle along a fence line and through a gate or to herd a calf back to her mother. After you’ve spent some time in the pasture playing with these concepts, you can get good enough to sort calves from cows for weaning in a holding pen without having to run them through a chute. You may be able to cut out a pair of cows from the herd when you need to get one in the chute. Never cut out and isolate a single cow. Cattle are herd animals, and they get panicky if made to go off by themselves; they may run over you to get back to their friends. Always work with at least pairs, if not triplets, and you’ll have much calmer animals.

When you are vaccinating, ear tagging, sorting, loading, or doing other chores that require moving the animals through the handling facility, there are a few other helpful tips for ensuring things happen smoothly, calmly, and without injuries.

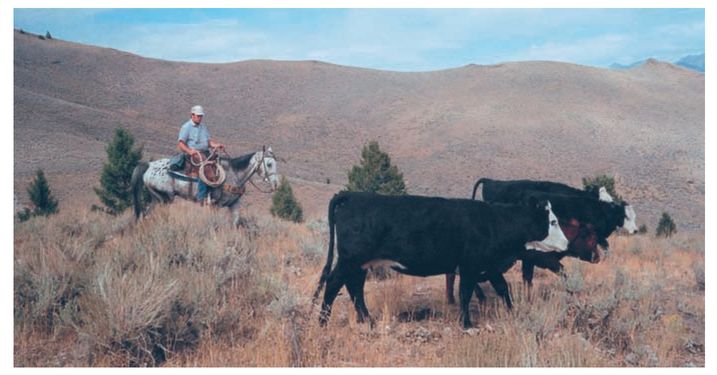

Putting gentle pressure on the flight zone, at the correct place, encourages these cattle to move in the right direction.

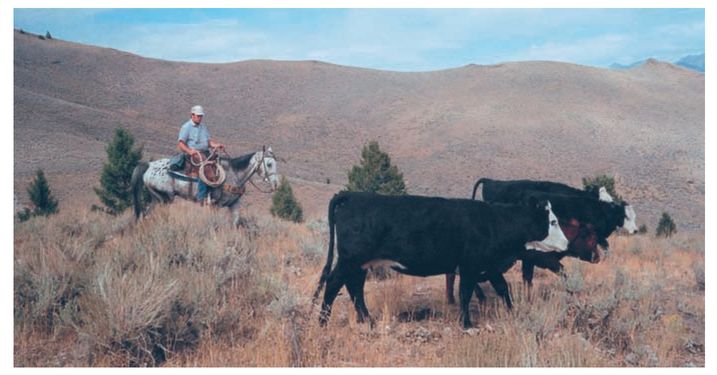

Accustom your cattle to your presence. Walking through this group of weaned heifers every day at feeding time gentles them.

ESTABLISHING A ROUTINE

Cattle love it when the same thing happens at the same time every day. Use this to your advantage by establishing a routine that makes your cattle familiar and comfortable with your handling facility. For example, if you’re feeding grain, you could feed it in the holding pen at about seven o’clock every morning. One side of our holding pen is lined with bunker feeders, so our cows like being in the pen. In fact, they’re usually waiting there for me at feeding time. When you feed, wear the same cap, carry the same grain bucket, and call with the same call. For the first week or so of establishing a routine, you may need to walk out in the pasture with a grain bucket to where the cattle can see you and then call to them. With new animals, I’ve even done a Hansel-and-Gretel routine, leaving a trail of little piles of grain leading back to the pen, where the big feed happens. Cattle catch on to the call and the grain bucket very quickly.

You could put the water tank in the holding pen, preferably on a nice cement pad to eliminate the mud. Leave the gate open so cattle can wander in anytime they’re thirsty. Once in a while, after they’ve had their grain or come up together for a drink, shut the gate behind the herd and make them stand in the pen for an hour or so. The more the cattle are accustomed to being in the pen, the easier it will be to put them there and keep them calmly waiting when you need to work with them. Even if you have only a couple steers for the summer, take the time to train them to be penned. Eventually, you’ll have to load them on a truck, and you’ll save yourself a lot of aggravation if they’re already penned when the truck shows up.

Did You Know?

You can avoid getting kicked when working around the back ends of cattle by “tailing” them. Raise the tail straight in the air with one hand, grab it around the base with the other, and keep it pulled toward the head. This keeps the animal’s hooves on the ground because kicking with the tail in this position hurts the animal’s back. Don’t be tentative about tailing; if you don’t have a good grip at the base, you can still get kicked.

If you’re rotationally grazing and switching paddocks regularly, that’s another opportunity to teach them to come when they’re called. Each time you change paddocks, do it at about the same time of day. Call the cows, then lead them to the next paddock. They’ll quickly learn to follow, and it’s wonderful to see them romp when they hit the fresh grass.

Of course, the cattle won’t know what you’re trying to do the first few times you switch paddocks. Wait until they come into the pen for grain or water, then close the gate behind them. While they’re getting a drink, go out and close the old paddock gate and open the new one. Then go back, open the pen gate, call the cows, and walk slowly out of the lane to the new paddock, calling as you go. Eventually, they’ll follow, and after a few repetitions, they’ll learn to follow immediately. They may even try to push past you in the lane. If they do, spread your arms, and give them a dirty look and a firm “cut it out” so they’ll learn you’re the leader and they need to mind. If one gets really pushy, rap her on the nose with a stick. This is another important point: remember that cattle have a herd hierarchy, and you should be at the top of it.

If you’ve got one big pasture, aren’t feeding grain, and aren’t even around on a daily basis, it’s still a good idea to teach the cattle that when you show up and they come to your call, good things will happen. Call them, let them see the bucket, then give them a treat in the holding pen. Use apples, carrots, or dried molasses. At first, just a few cattle will figure it out, but eventually they’ll all come. If there’s a holdout cow, you can either pen the others and wait till she shows up out of curiosity or pen the others, go out in the pasture, and gently herd her in. She’ll usually be quite willing to go where she knows the others went.

After a few months of calling and leading, the herd will usually come when you call and follow when you lead. This minor investment of effort is worth its weight in gold when it comes time to bring the cattle in for handling. If they aren’t accustomed to coming at your call, it means you’ll inevitably be out there some nasty cold morning, knowing the veterinarian is due in half an hour and wondering how in heck you’ll get them corralled in time. The cattle will quickly sense that you’re nervous and react exactly the way you’d expect any prey animal to react to a tensed-up predator type: they’ll be at the back end of the pasture before you’re through the front gate.

Did You Know?

Many farmers still use the age-old “come, boss” to call their dairy cows, which linguists believe traces back to the ancient Romans and the Latin bos for cow. Think how many thousands of years of routine that represents!

My cattle, recognizing the white bucket I carry as the one I feed them grain in, readily follow me. Train your cattle to recognize that good things such as grain come in certain containers, and they’ll follow you almost anywhere.

If you want to really get ahead of the game, train your cattle to exit the holding pen through the crowding tub and chute, just as they will on handling days. Close the gate behind the herd when they’ve entered the pen, and open the chute. I have a board cut to fit over the top of the headgate and hold it open so there’s no chance of it slamming shut on a cow. This teaches the cattle that the chute is the way out, and it saves you a lot of trouble getting them into the chute on the day you really need them to go. They’ll go by themselves, and they’ll think it was their idea!

All in the Timing

Unless you’re an early riser, I recommend scheduling paddock switches for the late afternoon. I used to do it first thing in the morning, until Gretel the cow took to standing at the barnyard gate around five o’clock, bellowing for me to hurry up. Since the gate is directly across from our bedroom window and I don’t like getting up at the crack of dawn, I soon realized I needed to change the routine. Unfortunately, although Gretel was a good cow and an excellent mother, she never figured out that the routine had changed. She kept bellowing. So I sold her. Sometimes, the best way to deal with a problem cow is to get her off your farm.

GETTING READY FOR HANDLING DAYS

Cattle are pretty specific about what they do and don’t like. As mentioned in chapter two, they like firm, nonslippery footing, and they like moving uphill and toward light. They dislike going into dark, unknown spaces; they detest loud noises; and they are afraid of strange objects flapping in the wind or glinting in the sun. They will follow each other around a curve, but they’ll balk at going into a chute when they can see the end is blocked. Keep these things in mind when you’re getting ready for handling days.

Presumably, your facility is already set up with curves and has good lighting. Now, walk around and make sure there are no soda cans, flapping chains, or glittery, fluttering debris anywhere. Make sure there are no broken boards on the floor of the chute. Oil the gates and levers on the crowding tub, alley, and headgate so they operate silently and smoothly.

Think through what you need to get done and how you’re going to do it. If you know ahead of time how you’re going to move the cattle through the pens, tub, and chute, it’ll be much easier for you to communicate the plan to them. Have a Plan B in case they don’t like Plan A. If you need only the calves, for example, or only the open cows, figure out how you can quietly sort off the ones you want and turn out the rest. Decide where you can keep the syringes, needles, and vaccines so they’re handy but out of the way of random hooves. Have the ear tags numbered and ready, with extras in case one falls into a fresh cow pie.

Good footing, good lighting, and a few curves in the layout make it easy to move cattle into a crowding tub and alley.

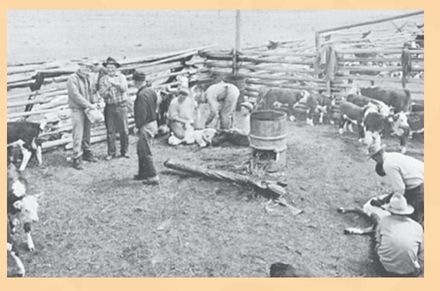

How Not to Handle Cattle

In the movies, cattle are handled with horses, lariats, and a big crew of cowboys. Calves are roped, flipped on their sides, and branded. It’s strenuous work, even with little calves, and for some reason filmmakers never do show how the cowboys vaccinate the full-grown cattle—not by flipping them on their sides with a rope, I’m sure. In real life, cattle are handled in all sorts of creative ways. Some owners with small herds will pen cattle against a wall or in a corner with a loose gate; some will crowd them so tightly in a small pen that the animals can’t move; and others will somehow get a rope around a cow’s neck and tie it up tight to a stout post. What these methods have in common is that they’re highly stressful to cattle, fairly unreliable as far as getting every head in a herd treated, and quite dangerous for both cattle and handlers.

HANDLING DAYS

Beef cattle are handled just a few times a year. In most areas, calves are castrated, and often vaccinated and ear tagged, in the spring. If you’re using artificial insemination, you’ll need to get the cows in the chute whenever they’re in heat, and you’ll want them to be calm. In the fall, you’ll vaccinate the whole herd, and heifers will get their brucellosis vaccinations from the veterinarian. If you haven’t ear tagged before, you’ll do this then. Two or three weeks later, the calves will be back for a booster vaccination. They’re also weaned then or shortly thereafter. In late fall, calves and cull cows are loaded into a truck or a trailer for a ride to the auction barn or a new owner, and fat cattle for your own freezer are loaded and sent to the processor. You may also occasionally have to pen a cow or calf that is sick or injured so you can treat her.

To accomplish these things on a cattle-handling day, you’ll need to sort off the cows, calves, or steers you want to work with, then move them into the chute and headgate. You’ll catch them one by one in the headgate, where you’ll administer vaccines, put on ear tags, or give some other treatment, then release them back to pasture. If you’re weaning the calves, you’ll need to sort them into separate pens or pastures—one for the cows and the other for their calves—as they come out of the headgate. The veterinarian, or the artificial insemination technician, or the truck for loading cattle may be around on handling day, too, and because cattle are very aware of strangers, this will add to the stress they’re already feeling from the change in routine.

Here I’m slowly crowding a pair of yearlings into the alley. Before squeezing your cattle with a gate, make they’re facing the right direction.

Once you have the cattle quietly penned and have given them a half-hour or so to calm down, the quickest way to get the job done is to move slowly. The faster you move, the more agitated the cattle will become, and the tougher it will be to get them into the chute. Don’t yell. Research has shown that loud noise, including yelling, is more upsetting to cattle than getting slapped or prodded. Use flight zone and pressure points to move a few cattle at a time from the pen into the crowding tub. Don’t fill the tub more than half full because cattle don’t like to be tightly packed. Wait until at least two or three are facing into the chute, then slowly move in the crowding gate. The cattle should start filing into the chute. Sometimes, you’ll have to back off on the gate to let a cow turn the right direction. You can wave a hand or herding stick gently in her face or pat a rump to get her to turn, but don’t yell and don’t hit. Things won’t go any faster, and for sure the cattle will be more difficult to work the next time.

Raise the gate at the end of the alley, and let a single animal into the chute. In a perfect world, it will walk up to the headgate with just the right momentum to make the gate close on the animal’s neck. In the real world, cattle sometimes come in so gently that the gate doesn’t close or so hard you’ll worry they’ve bruised their shoulders. With some of our old cows, I don’t bother putting them into the headgate if they’re calm enough to stand still while I give an injection.

For the cattle you need in the headgate that aren’t cooperating, one helpful trick is to walk quickly from their heads to their rumps; that usually makes them jump ahead. If the animals are reluctant to come down the alley, it may be because they see you standing at the end. Duck out of sight or walk quickly to the rear. Sometimes a pat on the rump or a tap with the stick on their hocks will do the trick. Be patient. Give them a little time. In the end, staying nice and easy will take less time than trying to rush them because too much pressure only makes cattle panicky and balky. A panicky cow may lose her head and try anything to get away—running over a handler, trying to jump a fence that’s too high and getting stuck halfway across, or trying to crawl under a gate and mangling the gate.

In the full swing of things, you’ll have a cow in the headgate, a couple behind her in the alley, a couple in the crowding tub, and the rest still in the holding pen, waiting their turns. Take care of the first cow, release the headgate, and make sure she gets safely out of your way into another pen or back to the pasture before resetting the headgate for the next patient. Look to see whether the next up is a calf or an adult, and adjust the gate accordingly. With practice, patience, calm, focus, and quiet, you should be able to vaccinate a herd of twenty to thirty animals in well under two hours, without getting any manure splattered on your pants. But wear old pants just in case.

LOADING AND TRANSPORTING CATTLE

Getting cattle on a truck or trailer breaks some of the rules for cattle handling. You’re asking them to go into something that’s dark and a dead end, and it’s an unfamiliar step up to get there. Once again, have some patience. If you are loading into a low trailer, you can load directly from your chute. You can use a pair of loose gates on either side to fill in any gap between the headgate and the trailer gate; if you do this, tie the gates down. If you’ve got enough cattle to warrant bringing in a semitrailer, you’ll need a ramp or some other device to get the cattle up to the level of the truck. Ramps are available commercially, or you can build your own. Semitrailers need a lot of room to maneuver, so put the ramp where the driver will be able to turn and back up easily.

With his head firmly caught in the headgate, this steer can be safely treated. A simple release mechanism lets him out when you’re done.

Advice from the Farm

Handling Cattle

Our experts offer some advice on dealing with cattle in various situations.

Extend Your Reach

“At times, it is helpful to impress the cows with size. I either hold my arms out to my sides, like I learned to do when playing basketball as a kid, or carry my trusty ‘cow chasing stick,’ which extends my reach to the side. This stick is not used to strike an animal; it just gives the illusion of size. When I get in pretty close proximity to the cows, I start making a kind of sshshsshsshh noise. It gets their attention. When I want them to move, I change the noise to more of a shhooo, soft and low-pitched. I want them to move quietly, not run.”

—JoAnn Pipkorn

Build Strong Gates and Fences

“Have a series of gates and fences of reinforced metal or wood for cattle handling. If they start tearing stuff down, they learn that they can, and you’ve got trouble. One of the most important things we have now in the industry that we didn’t used to have is the self-catching headlock. Have a swing gate on at least one side. It makes you willing to do some of those chores you’re supposed to do.”

—Rudy Erickson

Have an Exit Strategy

“One thing I always do, and it’s something my Dad did, is whenever we have beef cattle out in the field we always have a piece of machinery, like a wagon, in the field. I tell the boys if something starts coming after you and you can’t get under the fence, then get under the machinery or on the other side of it. Basically I keep the boys out of there when we have the bull. And you don’t want kids running around in the pasture when the cattle are just getting outside in the spring and they’re feeling goofy. You can never trust a bull, and you have to have an exit strategy.”

—Randy Janke

Cull Troublemakers

“Don’t be afraid to cull cows. If you have a fence jumper, or one that bellows constantly, get rid of it! It’s not worth the aggravation. We had a cow that never was quiet that had a nice heifer calf. After that calf was weaned, mama went to the butcher shop. It was much more pleasant around the farm after that!”

—Linda Peterson

If you’re moving just a few cattle, get them into the crowding tub well before the truck pulls in. Because the noise will upset them, it’s best to have them as far along in the process as possible before they begin to tense up. Once the truck or trailer is in position, begin moving the animals down the chute. The one in front, with the best view of where this is all going, will probably be reluctant. The ones behind may begin pushing the leader along, which is usually OK. Don’t rush things. Give the steers time to look at the step.

You will probably need to use a little more persuasion than you would in other handling situations. Have any helpers stand out of sight of the cattle, or try walking quickly from the head of the line to the back. You can slap a rump, but don’t yell and don’t whip out the electric cattle prods. For one thing, it will cost you money because stressed cattle on their way to auction, the processor, or a buyer have more “shrink,” or weight loss, than do unstressed cattle. Michigan veterinarian Ben Bartlett even worked out the math back in 2002. He was selling a truckload of steers, which are sold by the pound, with weight calculated by weighing the truckload. If a steer got upset and pooped before it got on the truck, as happens when one is excited, and the average cow pie weighs seven pounds and is therefore worth about $5, then Dr. Bartlett figured he was losing $300 on a load of sixty steers, just from being in too much of a hurry to get them loaded. Stressed animals won’t eat or drink either, so they’ll lose more weight in the pens at the auction barn, a second type of shrink. Stressed animals also release a lot of adrenaline into their bloodstream, which darkens and toughens their muscle. These animals are known as dark cutters, and their meat is less valuable.

These cattle are being calmly loaded for transport.

AFTER HANDLING DAYS

The day after you’ve worked cattle, go back to the same old routine. You want to erase the bad impressions of the day before with all the good things that will continue to happen if they come when called and follow when led. They won’t forget about getting shots or tags, but getting the grain or water and remembering that the quickest exit is through the chute will gradually become uppermost in their minds again. And really, it wasn’t that bad. Except for the stop in the headgate and the needle jab, it was all part of the routine.