CHAPTER SIX

Keeping Beef Cattle Healthy

Beef cattle raised outdoors on pasture and hay are naturally hardy animals and tend to have few health problems. When they do become ill or injured, it’s important to identify the problem and treat it quickly, before it worsens and causes permanent damage to or kills the animal. As a cattle owner, you have a responsibility to take the necessary steps to prevent problems, to recognize abnormal behavior immediately, and to treat minor health problems or call the veterinarian for conditions beyond your skill. Your cattle health program, then, should have three parts: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

PREVENTION

Preventing your cattle from becoming sick or injured is much easier than dealing with a half-ton patient that has no interest in your nursing or a vet’s ministrations. Start your “cattle wellness” program with these few simple actions.

BALANCED DIET, EXERCISE, AND SHELTER

Like humans, cattle are healthiest when they get enough exercise and plenty of fresh air, are kept warm and dry in cold weather and cool in hot weather, and eat an adequate diet that includes the necessary vitamins and minerals. As discussed in chapter four, they also need salt and clean water available at all times, although it doesn’t hurt them to have to walk a distance in order to get to the water—that can be part of their prescribed exercise program. In addition, maintaining a lowstress environment and a regular routine will contribute a great deal to the overall health of the cattle.

VACCINATIONS

Along with good nutrition, water, and shelter, the best and cheapest insurance against cattle disease is vaccination. Every cattle owner should work with a veterinarian to develop a vaccination program appropriate for the ages and types of his or her cattle and for the region.

Cattle Diseases and People

A number of cattle diseases are transmissible to people. Tuberculosis can be transmitted through raw milk from infected cows as well as through the air in poorly ventilated barns and sheds. Although tuberculosis is now rare in cattle, it does still occur. Five herds in Minnesota, totaling nearly four thousand head of cattle, were destroyed in 2005 after some of the cattle were found to be infected, and states with recent cases of tuberculosis in cattle or deer are subject to animal transport restrictions.

Brucellosis, or Bang’s disease, in cattle is transmitted to people through raw milk or during the delivery of calves from infected cows, in which case it is called undulant fever. Anthrax can be transmitted when people handle infected meat or hides, as can foot-and-mouth disease. Cattle owners can also acquire mange, ringworm, toxoplasmosis, leptospirosis, and tapeworms from their animals, though, thankfully, none of these afflictions is common in people today.

All the same, it’s a good idea to keep your cattle vaccinations up to date and your premises clean and well ventilated.

Types of Vaccinations

Every program should include calfhood vaccinations and annual booster shots for adult cattle. In the past, combination vaccines were often formulated to address only diseases that were a problem in the region in which the cattle lived. Today, with cattle traveling so often and so far in the United States, it’s standard to give all cattle a nine-way vaccine that covers bovine rhinotracheitis, viral diarrhea, parainfluenza, leptospirosis, and several other diseases.

A nine-way does not cover the clostridial diseases, which include tetanus, botulism, anthrax, “wooden tongue” (actinobacillosis), and blackleg. There are vaccines for these, but because they’re hard on the animal and those diseases aren’t common in cattle in northern Wisconsin, where we live, they aren’t usually recommended here. They are recommended, and sometimes required, in many other areas. Check with your veterinarian to determine whether any of the clostridial diseases are common in your area. If so, even if there’s no legal requirement, it’s worthwhile to vaccinate because these illnesses are difficult to treat and can kill animals in as few as twenty-four hours.

It’s also possible to vaccinate against rabies, but again, this usually isn’t done if rabies is not a problem in the area.

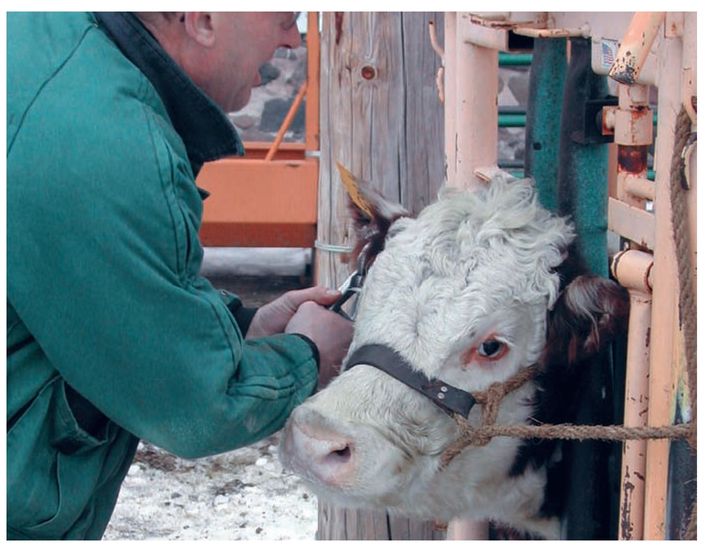

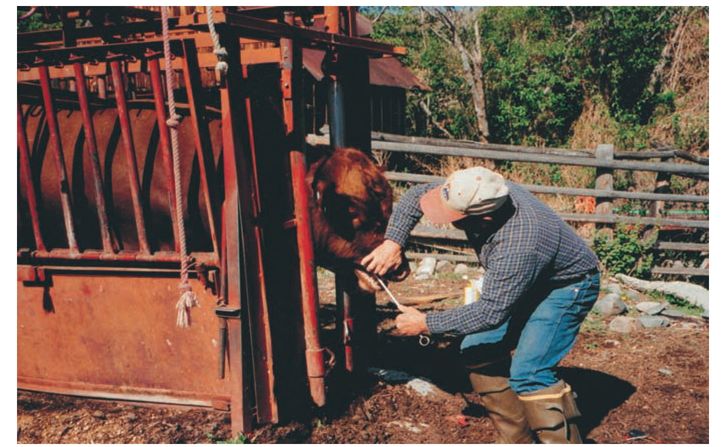

Brucellosis, also called Bang’s disease, causes abortions and fever in cattle and undulant fever in people. Undulant fever is all but forgotten now in the United States but is still fairly common in other parts of the world. It’s transmitted through contaminated meat and unpasteurized dairy products. Brucellosis vaccination is cheap insurance against abortions in your herd. The shot must be administered by a veterinarian when the heifer is between four and eleven months of age. After giving the vaccination, the veterinarian will attach a metal ear tag to the heifer’s ear and officially record the shot.

A veterinarian tattoos a young heifer after giving her a brucellosis vaccination. The heifer is held securely in the chute by a headgate and halter.

Did You Know?

When a cow has hardware disease, it means she has somehow eaten some stray bits of metal and they have perforated her stomach, making her sick. As a preventive measure, some farmers use a balling gun to feed their cattle cow magnets. These are cylindrical magnets about five inches long and an inch in diameter. The magnets lodge in the reticulum and attract all the metal bits that may be there, keeping them from washing around and doing damage. Not all veterinarians believe in the effectiveness of using magnets, however, so it’s better for you to harvest any metal pieces on your land before your cattle do. Patrol your pastures.

When to Vaccinate

Calves are often vaccinated for some things soon after birth, but many beef cattle owners rely on the immunity the babies get from their mothers’ colostrum, or first milk, for the first few weeks and wait until it’s nearly weaning time—at four to eight months of age—to vaccinate. These older calves should be given booster vaccinations two to four weeks after receiving their first vaccinations. Dairy and orphan calves should be vaccinated by two weeks of age, since they aren’t getting ongoing immune protection from their mothers’ milk, and again at about six months.

Calves can be vaccinated shortly after birth, or you can rely on the protection of the mother’s colostrum, or first milk. Talk to your vet about what is best for your area.

Adult cattle should get an annual booster vaccination. Years ago, cows needed to receive their booster vaccinations before they were bred because some of the vaccines could cause abortions or birth defects. A new generation of vaccines now allows most cows to be vaccinated after they’ve been bred, but check with your veterinarian to make sure that these boosters are given at the proper time for your cattle and for your region.

Vaccines need to be kept properly refrigerated and replaced once they pass their expiration dates. They lose potency after those dates. Buy your vaccines from your veterinarian, who will have been careful to keep them cool. Don’t mix vaccines unless it says specifically on the label that it’s safe to do so.

Injection Methods

Most vaccines are injected into the muscle. This is called an intramuscular (IM) injection, and it’s the simplest type to give. Use a 2-inch, 16-gauge needle for adult animals and a 1 ½-inch, 18-gauge needle for calves. Although IM shots have traditionally been given in the rump, don’t do this. It tends to make a permanent lesion in some of the most valuable meat. Give injections in the neck. Slap the animal’s neck a few times, then pop the needle in quickly and deeply with a firm stroke, and depress the plunger. The animal will probably jump, so don’t have your arm between him and any sort of bar, where you could get caught and end up with a broken limb. Change needles often because the tough hides quickly make needles dull, and a dull needle hurts more and is harder to push in than a sharp one.

Another type of injection, the subcutaneous (sub-Q) injection, is given just under the skin and is used for many types of medications. This one takes two hands and a few seconds longer than IM injections do. Making sure your arms aren’t in a position in which they might get trapped by a plunging cow, grab a pinch of skin between your thumb and forefinger, use your other hand to quickly push the needle lengthwise into the bottom of the fold, then depress the plunger.

The third type of injection, into a vein (intravenous), is used infrequently and should be done by a veterinarian or someone with experience.

The veterinarian can do all your vaccinating for you, but most cattle owners learn to do it themselves. I use a handy device I found at the farm store that’s shaped like a pistol. It contains a big syringe that holds up to ten doses of vaccine. The calibrated trigger delivers exactly the right dose with each injection, and I can vaccinate a whole line of cattle without having to reload the syringe. Change the needle every two or three animals, and always use a new, separate needle to draw vaccine out of the bottle into the syringe so you don’t contaminate the vaccine. Syringes can be reused if you clean them carefully with soap and hot water and dry them thoroughly. Needles can be cleaned, sharpened, and reused, but they’re cheap and it’s generally easier to replace them.

Finally, set up a little table or an apron or some other clean and convenient place with the vaccine bottles, syringes, needles, record book, ear tags, and other equipment you’ll need. Having everything handy and organized, but out of the way of the cattle, is easier—and safer—than trying to hold the ear tagger in your teeth and storing the syringe behind your ear.

Vaccinating cattle in the neck rather than the rear end, as has been traditional, prevents blemishes in some of the most valuable cuts.

Cattle Medical Kit

You should have a few basic supplies on hand for treating sick or injured animals. You can add others as the need arises or your veterinarian advises.

The pieces of equipment you definitely want to include in your cattle medical kit:

• Balling gun—for getting pills down the throat

• Rectal thermometer—when using, put a long string on it; many thermometers have disappeared into cows because of an unexpected muscle contraction

• Rope halter and stout rope (couple lengths)—the halter and rope for holding a head still in the headgate and just the rope for pulling a calf during a tough delivery

• Stomach tube—for administering fluids and medications orally and relieving bloat if you’re a long way from a veterinarian or are planning on doing a lot of treatment yourself

• Suturing needles and thread—for stitching cuts

• Syringes and needles—for administering medications

A rope halter often isn’t necessary for the basic supply kit, but the rest of the equipment here is: a loaded ear tagger with extra tags and studs, a bottle of 9-way vaccine, syringe, a syringe gun, and a notebook and pencil for recordkeeping.

•

Trocar or sharp knife—for sticking bloated cows

A few medications you’ll want to have available that are simple to use and keep well:

• Baking soda—for easing stomach upsets in calves

• Epsom salts—for digestive upsets and soaking sore or infected feet

• Iodine—for treating wounds and for dipping navels on newborn calves

• Topical antibiotic—for treating pinkeye and other skin infections

INTERNAL PARASITES

Many different types of worms like to live inside cattle. The most common parasites are roundworms, lung worms, liver worms, liver flukes, and pinworms. Most cattle owners treat with dewormer medication once or twice a year: in early spring before grazing starts, in late fall after grazing is done for the season, or at both times. For the most effective control of worms, discuss with your veterinarian the best time of year to deworm in your area and how to rotate deworming medicines for better results. Worm medicine is widely available at farm supply stores and from your veterinarian. It is either poured along the back or injected.

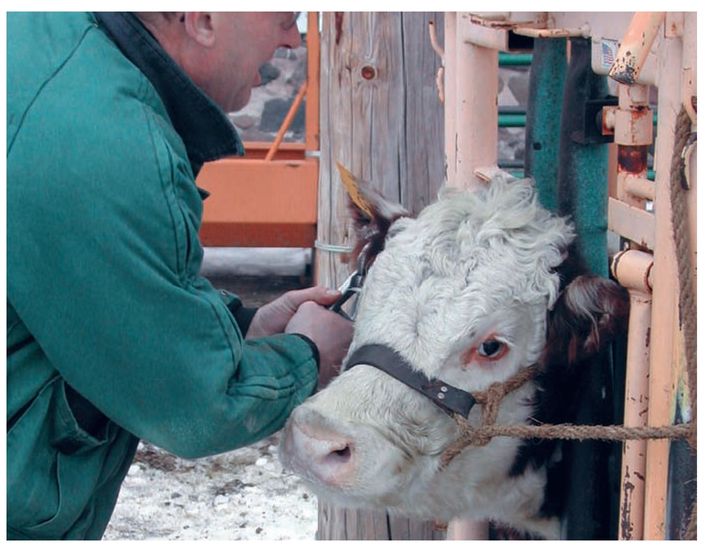

Cattle are deloused in the squeeze chute with a pour-on medication. In areas where it’s necessary, cattle should be treated for lice and grubs in late fall.

Concern has risen recently about the increased resistance of internal cattle worms to available medications, and some veterinarians are recommending that cattle not be treated unless worms are really causing a problem. Worm infestation levels are calculated by taking a manure sample and examining it under a microscope for worm eggs, something that can be done only by your veterinarian (although you get to collect the sample). It’s easier to first keep a close watch for external signs of a worm problem—weight loss and a dull coat in the summer (lacking the smooth, glossy shine).

Another common internal parasite is cattle grub, the immature stage of heel flies. They live inside cattle until they become adults, then emerge by drilling a hole in the hide of their host. Timing of treatment is crucial to controlling cattle grubs and varies by region. Talk with your veterinarian about your options.

Because internal worms are transmitted by cattle eating grass infected with worm eggs from previous manure deposits, it’s possible to reduce worm infestations by managing pasture rotations. Don’t return cattle to a paddock until worm eggs deposited in the manure from their last rotation have had time to mature and die. For specific information on the life cycles of different worm species (which vary somewhat by moisture and temperature), consult your veterinarian or university extension service.

Some level of internal parasites is almost inevitable in pastured cattle, but it’s usually not a problem unless the infestation is affecting a cow’s general health and reducing her resistance to other diseases or slowing weight gain. Gear your treatment to both the nature and the extent of the problem.

EXTERNAL PESTS

Several species of flies delight in tormenting cattle. Cows afflicted with horn flies, face flies, heel flies, or stable flies might run around with their tails in the air trying to get away or quit grazing and bunch together tightly, even on hot days, trying to reduce the amount of hide exposed to bites. When this happens, it’s time to do something.

If your cattle are tame and you have time, you can spray them daily with a fly repellent. More economical are medicated ear tags or a repellent-soaked rope or post in the barnyard that the cattle will use for scratching, which you can buy or construct yourself. Inside sheds, you can hang flypaper, long sticky strips that trap flies, or use a light trap or baited trap.

Taking preventive measures to destroy fly-breeding areas will save a lot of money in fly killer. Horn flies lay their eggs in fresh cow pies. If you develop a horn fly problem, try dragging paddocks with a harrow or any sort of homemade drag after grazing to break up the manure pats. Something as simple as an old bedspring behind a car or an ATV (all-terrain vehicle) will work. Stable flies, by contrast, breed best in the mix of old manure and hay that builds up in a ring around round bale feeders. Cleaning up feeding areas in the spring by removing the detritus will nip a lot of stable fly infestations in the bud. To reduce other flies, in general, keep feeding and watering areas as dry and as free of manure as possible. Some cows seem to have more problems with flies than others (no one knows why). Any cattle that have considerably more fly problems than the rest of your herd should be considered for culling.

Cattle spend a lot of energy and grazing time swatting at flies when fly populations are high.

Advice from the Farm

To Their Health

Our experts offer some advice on taking good care of your cattle.

Keep a Close Eye

“How do you spot a sick animal? With my cattle it’s really easy—if I take feed out and one is slow coming up, I know something’s up. The best way is to check on them every day. I have it a little easier because they’re close (to the house). If I walk out to the barn, they’re talking to me. I keep a real close eye on them. The meek one, for example, it’ll walk up to me and I’ll pat it on the forehead and I know it’s feeling fine. If it doesn’t do that, I know something’s up.”

—Randy Janke

When in Doubt, Call!

“When action is needed, your response may range from catching the animal for closer examination and treatment to calling the vet. When to call the vet is a matter of your comfort level, knowledge, and experience. This is where a knowledgeable and experienced neighbor can be very helpful. Such a neighbor can demonstrate the way to take a temperature or inspect feet or take one look and say, ‘Call the vet.’ If there is ever a question in your mind about whether to call or not to call a neighbor or vet, call! It’s better to look a little overreactive than to lose an animal.”

—Sherri Schulz, DVM

Set Up a Health Program

“Spotting sick animals is, I think, one of the things that is hard to teach. Check who comes to the feed bunk. If one doesn’t come up for feed, it may not be feeling well. If you get a sick one, it’ll be standing in the shed or breathing heavily. They recuperate faster if they’ve had their shots. Another important point is that it’s really important to have a vet work with you to lay out a good vaccination program. You don’t know all the answers, and it’s critical that you get a good product and know how to use it. With some of these new vaccines, if you don’t have the herd vaccinated, you shouldn’t use it in the calves because it can cause all kinds of side effects.”

—Rudy Erickson

Rinderpest

Disease epidemics in cattle—from foot-and-mouth disease to tuberculosis—have a long history of destroying livelihoods and devastating entire countries. The worst of them has probably been rinderpest, a highly contagious viral disease characterized by fever, loss of appetite, bloody diarrhea, and for most of its victims, death. Although it’s unknown in the United States, rinderpest is feared throughout Asia and Europe. Rinderpest was brought to Africa in 1889 by cattle imported from India and southern Russia to feed Italian troops. The resulting epidemic destroyed 80 to 90 percent of all cattle in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as killing large numbers of sheep, goats, buffalo, giraffe, eland, antelopes, and wild pigs. The loss of livelihood ruined the social structure of nomadic herding tribes and caused widespread poverty and starvation. The disease returned to Africa in 1982–1984, causing an estimated $500 million in cattle losses. When Dr. Walter Plowright developed a vaccine against rinderpest in 1999, he was awarded the $250,000 World Food Prize. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations predicts that the vaccine will make it possible to eradicate rinderpest globally by 2010.

Cattle can also suffer from ticks, lice, and mites. Cattle that spend a lot of time scratching themselves on feeders and fence posts probably have lice and should be treated with a spray or powder. Follow the application directions exactly, and don’t mix lice treatments with other insecticides. Tick control comes in the form of sprays, dips, and dusts. Scabies mites cause small sores and scabby areas, and mange mites cause thick, wrinkled skin. Roundworm, common in the winter, causes bare patches on the hide. For these problems, talk to your veterinarian about establishing effective control and treatment.

RECORDKEEPING AND ANIMAL IDENTIFICATION

Keeping a notebook to record vaccination, birth, weaning, breeding dates, and other important information for each animal in your herd helps keep your herd’s health and breeding programs on time and on track. After a few years of recordkeeping, you’ll be able to pick out which animals are healthiest, which breed back the quickest, and which raise the best calves. You’ll also be able to cull the cows that are most susceptible to health problems, are poor performers, or have bad dispositions. The result will, I hope, be a herd of uniform, docile, healthy cows that are a pleasure to own and for which you will always have buyers for the calves.

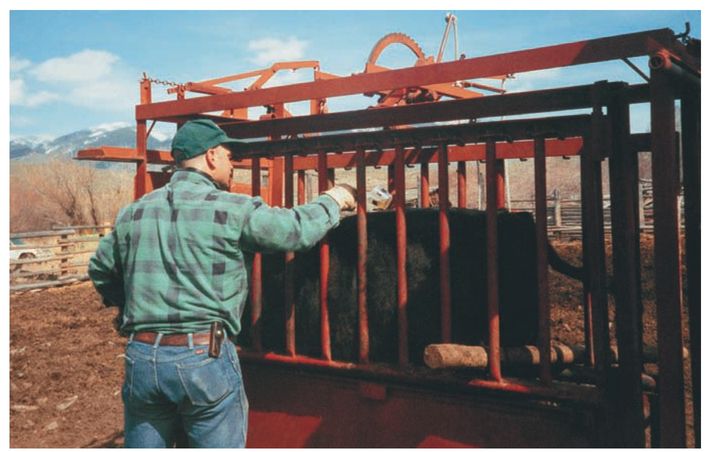

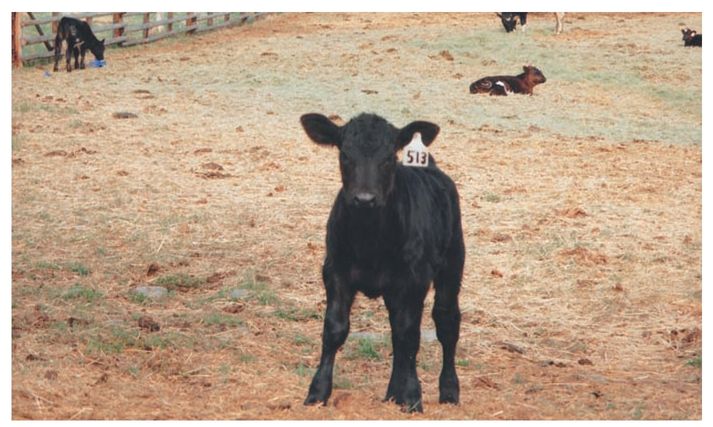

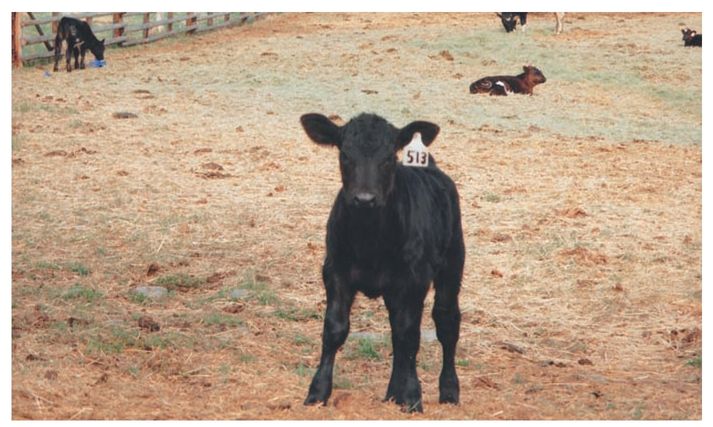

Individually numbered ear tags allow you to keep good records of your animals for your breeding program and health concerns.

Recordkeeping also plays a crucial role in U.S. animal-health initiatives. Recent outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease in Britain, of anthrax and tuberculosis in U.S. cattle herds, and of bovine spongiform encephalopathy—mad cow disease—in several countries have fueled a U.S. government initiative to establish a national cattle identification system. The hope is that by identifying each animal individually and tracking the animal’s movements, any disease outbreak can be quickly traced to its origins, then suppressed. The United States’ scrapie eradication program for sheep already includes an animal identification system, and pig farmers are also moving in that direction. Recently, my state, Wisconsin, established a Premises ID registration as an animal health measure, requiring all livestock owners to register their location and type of livestock owned with the state. Eventually, cattle owners across the country will be required to identify and keep records of each animal in their herds.

For cattle owners who already identify individual animals for their own records and breeding programs, a national animal identification program to control disease outbreaks will require very little extra effort. The standard identification method for cattle is numbered ear tags. The tags and tool for attaching them are available at farm supply stores. Get the large tags; the hairy ears of cattle make it hard to read the little ones. You can buy tags that are already numbered, or you can get a special marker and blank tags and do the numbering yourself. Attach the tag when you’ve got the animal in the headgate for vaccination, and put it in the center of the ear. Tags too close to the edge have a tendency to rip out. Make sure the tag is on the front side of the ear and the number is facing forward.

Cattle can also be traditionally branded, freeze-branded, or tattooed. These methods require more equipment and are much more painful for the animals. For most small herds, ear tags are more than adequate, with the added advantage of being cheap, quick, and easy to use.

HOW TO TELL WHEN AN ANIMAL IS SICK

You can’t identify a sick animal until you know how a healthy animal looks and behaves. That’s why it’s important to spend time on a routine basis just watching your herd. Become familiar with how your cows walk, lie down, get up, chew their cud, lick themselves, stretch, scratch, push each other around, and take care of their calves. This can be a delightful task. When our cows are in the paddock next to the house, there’s nothing more pleasant than taking a cup of coffee out on the deck and watching the cows. Summer evenings are especially nice, when it cools off and the calves get frisky. They’ll race around the cows, butt heads, and buck. Sometimes the cows come over and watch us.

Did You Know?

The fact that cattle appear not to sleep would make it difficult to succeed in the legendary sport of “cow tipping,” in which one is supposed to sneak up on a sleeping cow and tip her over. In his 1974 book Farm Animal Behavior, Andrew Fraser notes that no concrete evidence exists that adult cattle actually sleep. If they do, it is only for short periods, although they will rest without appearing to sleep for nine to twelve hours a day. Normally, they will rest by standing or lying on their stomachs, although they will lie on their sides for short periods. If you see a cow on its side for longer than an hour, something may be wrong.

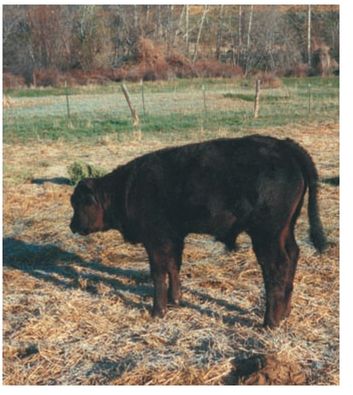

This calf, with its head down and back hunched, looks uncomfortable and may be ill.

Once you know what’s normal for your cattle, you’ll be better able to spot abnormal behavior or appearance. If you get into the habit of regularly taking a good look at each animal, you’ll catch problems early. Early diagnosis and treatment is half the battle when it comes to curing a sick or injured animal. A cow that goes off by itself and is not grazing with the others is reason for concern. A cow that is not chewing its cud, spends an abnormal amount of time lying down, has inflamed eyes, shows no interest in its surroundings, or is lame or moves only with effort should be examined more closely. A cow that kicks at its belly, stands still with its back arched, has watery diarrhea, or looks like it’s been pumped up with an air compressor needs immediate attention. A calf with watery diarrhea or labored breathing should also be examined immediately.

Cattle pills are given with a balling gun—a technique you can learn from a vet or an experienced neighbor.

WHAT TO DO WHEN AN ANIMAL IS SICK

A good veterinarian, a manual of cattle ailments, and a basic medical kit (see “Cattle Medical Kit”) are your lines of defense against problems. (Although a list of all the injuries and illnesses that can afflict cattle is beyond the scope of this book, there is a list of the most common ailments in the Appendix.) When you have an animal that is injured or not acting or looking normal and it’s not obvious what to do, call your veterinarian and get her advice. You may be able to deal with the problem yourself, or the veterinarian may prefer to make a farm call. If the animal is walking, get him into a clean, bedded pen for observation and treatment or into the chute if that’s more appropriate.

As you gain experience with cattle, you’ll learn to recognize and to treat minor problems. With good preventive measures and good luck, the only time you’ll see your veterinarian is once a year for brucellosis vaccinations and to fine tune your cattle health program.