1. MONKEY THEATER

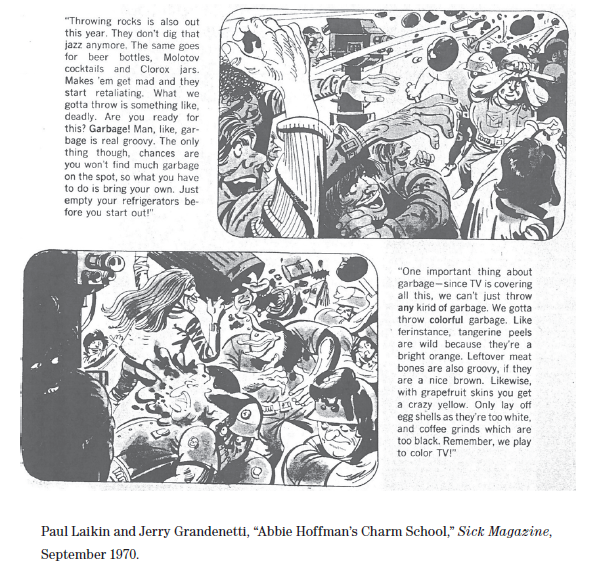

IN A 1970 COMIC STRIP TITLED “ABBIE HOFFMAN’S CHARM SCHOOL,” Paul Laikin and Jerry Grandenetti lampooned Hoffman, the Yippie “leader” and media darling, for appearing to revel in his ironic celebrity status. The strip depicts Hoffman guiding students through a course in the etiquette of activism in an age of media saturation, telling them, for example, that when protesting, what one yells at the “pigs” is of great importance: “No more four-letter words. Remember, you’re on TV and they’ll bloop you out. We must use different kinds of obscenities suited to the medium. Obscenities that will really shock the TV viewer. Like, for example, instead of yelling ‘You filthy pig!’ at a State Trooper, we yell ‘You have bad breath!’”1 Later, Hoffman tells the class that throwing rocks at the police

is also out this year. They don’t dig that jazz anymore. The same goes for beer bottles, Molotov cocktails and Clorox jars. Makes ’em get mad and they start retaliating. What we gotta throw is something like, deadly. Are you ready for this? Garbage! Man, like, garbage is really groovy. . . . One important thing about garbage—since TV is covering all this, we can’t just throw any kind of garbage. We gotta throw colorful garbage. Like ferinstance, tangerine peels are wild because they’re a bright orange. Leftover meat bones are also groovy, if they are a nice brown. Likewise, with grapefruit skins you get a crazy yellow. Only lay off egg shells as they’re too white, and coffee grinds which are too black. Remember, we play to color TV!2

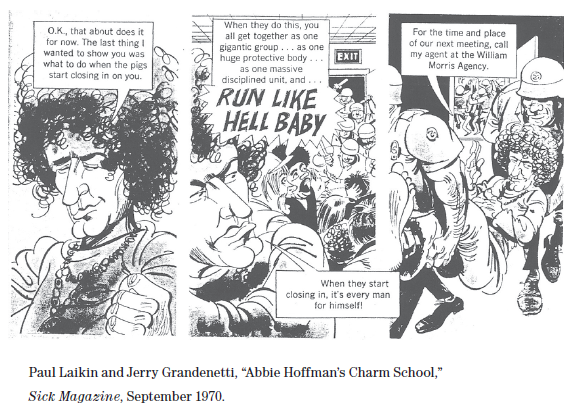

Finally, with the police moving in to adjourn the class and administer beatings, Hoffman feels compelled to tell his students what to do “when the pigs start closing in on you.” Faced with the threat of real violence, however, he loses his studied cool, breaking off midplatitude to shout, “RUN LIKE HELL BABY. . . . When they start closing in, it’s every man for himself!”3 And, almost predictably, as the police carry Hoffman away he reminds his students that they should “call my agent at the William Morris Agency” for the time and place of their next meeting. While not as nuanced as some of the arguments concerning Hoffman’s political work, Laikin’s and Grandenetti’s cartoon nonetheless spoke to the anger that a number of activists felt toward “movement celebrities.” Seemingly co-opted by their own stardom, these “leaders” appeared incapable not just of speaking for their own constituents but of speaking meaningfully of opposition at all.

But what if the point of Hoffman’s activism—or media mythmaking, as he called it, indicating the extent to which his approach to political action was inseparable from the creation of falsehoods and tall tales—was not so much to use the media as a means of broadcasting “real” revolutionary views or “correct” revolutionary ideology as to turn the apparent futility of opposition into its own form of historically and technologically mediated resistance? To answer this question, I would like to look closely in this chapter at Hoffman’s political actions, and at the arguments of a number of his critics. I will look, specifically, at the work of Emmett Grogan, founder of the San Francisco–based guerrilla theater group known as the Diggers, and Theodor Roszak, the author who in 1968 coined the term “counter culture,” defining it explicitly in opposition to “extroverted poseurs” like Hoffman. Finally, I will turn to the criticisms of activist and independent filmmaker Norman Fruchter, who in 1971 argued that Hoffman had only betrayed the youth culture for which he claimed to speak. For each of these commentators, Hoffman’s version of political activism was ultimately counterproductive because of its relation to the mass media. Quite interestingly, however, the arguments of Roszak and Fruchter, like those of Robert Brustein, were each based primarily in a reading of the works of one of Hoffman’s mentors, Herbert Marcuse. Drawing on Marcuse’s works of the 1950s and ’60s, these authors dismissed Hoffman for his apparent faith in the media’s ability to aid in bringing about revolutionary social change. Hoffman’s willingness to engage the media, they argued, merely indicated the extent to which he had mistaken images and performances for reality. By looking at the ways in which Hoffman courted the media, however, one might argue, to the contrary, that his antics took Marcuse’s work more seriously than any of these authors recognized, and that, in turn, his media mythmaking may have been most radical precisely when it seemed to these authors most compromised.

While Brustein, as I have explained, depicted contemporary calls for “revolution” as little more than hubris and delusion, a number of activists had intentionally embraced theatricality in hopes of exploiting what appeared to be a historical inability to distinguish between aesthetics and politics. The Diggers, for example, were a loosely organized offshoot of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, conceived in 1966 by Emmett Grogan, Billy Fritsch, and Peter Berg as a type of performative resistance to the commercialization of the “hippie” counterculture. In opposition to the Haight Independent Proprietors (HIP), a group of merchants looking to capitalize on San Francisco’s reputation as the epicenter of the emerging youth culture, the Diggers served free food in Golden Gate Park, offered free “crash pads” for those who had nowhere to sleep but on the street, opened a free store that gave away anything from clothing and shoes to money and marijuana, and attempted to establish a free medical clinic with the help of local doctors. These services were necessary, the Diggers believed, because the HIP’s reckless promotion of San Francisco’s counterculture had brought on not a “summer of love” but a throng of runaways. There was simply no way of accommodating this swarm of homeless, penniless young men and women. The free food, clothing, and shelter the Diggers’ sought to provide, therefore, were largely designed to avert a potentially disastrous situation.4

What is important about the Diggers’ Robin Hood–style charity work—items they offered for free were often stolen from stores, delivery trucks, and so on—is the way in which they described their “social work” as a form of theater. In 1966 Berg wrote that the group’s actions were in fact a new form of dramaturgy.5 The Diggers were not, he insisted, simply offering food, clothing, and shelter, but performing a utopian future. In the essay “Trip Without a Ticket,” Berg argued that the Diggers’ brand of activism was, simply put, “Ticketless theater”: “It seeks audiences that are created by issues. It creates a cast of freed beings. It will become an issue itself. . . . This is theater of an underground that wants out. Its aim is to liberate ground held by consumer wardens and establish territory without walls. Its plays are glass cutters for empire windows.”6 For Berg, the significance of the Diggers’ guerrilla theater lay in its ability to bring about real change in real time. By collapsing the distinction between theater and everyday life, it allowed individuals to become “life-actors.” Rather than performing predetermined roles that ended with the play, actors and audience together would use their skills and imaginations to bring an alternative reality into existence. If individuals could realize this capability, Berg argued, virtually anything was possible. Social change would no longer be something that required plans and strategies; it would simply happen: “Let theories of economics follow social facts. Once a free store is assumed, human wanting and giving, needing and taking, become wide open to improvisation.”7

Frustrated not only with the marketing of “hippie” culture but also with the plodding, ineffectual political work of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Diggers took their “ticketless theater” to Denton, Michigan, in the summer of 1967 to disrupt SDS’s “Back to the Drawing Boards” conference. The seminal organization of the student New Left, SDS had planned their annual conference hoping to bridge a widening gap between the organization’s founders, who were no longer students, and its younger “prairie power” members, who had taken on active roles in local offices throughout the country, and who were far more amenable than their predecessors to the ideas of the counterculture.8 As the conference opened with Tom Hayden delivering the keynote speech, Grogan, Fritsch, and Berg burst through the door. They seized the microphone, accused SDS’s members of being more concerned with maintaining organizational structure than bringing about real social and political change, and angered the “straight” SDS’ers with their macho posturing.9 SDS was no longer the “New Left,” the Diggers suggested; the Diggers were. “You’ll never understand us,” Grogan told them. “Your children will understand us.” Then, exposing perhaps the most obvious political blindness of much of the counterculture and New Left, he called the men in the room “faggots” and “fags,” shouting “You haven’t got the balls to go mad. You’re gonna make a revolution?—you’ll piss in your pants when the violence erupts.”10 For the Diggers, SDS was, in every sense of the term, impotent. In spite of the organization’s stated desire to reassert the social and political significance of the individual, their refusal to abandon the form of a rigidly organized political movement had done just the opposite.11

As former Digger Peter Coyote has written, “Ideological analysis was often one more means of delaying the action necessary to manifest an alternative.”12 Guerrilla theater offered a way of moving beyond the inevitable difficulties of “participatory democracy” through immediate, direct action. As Grogan told the members of SDS, “Property is the enemy—burn it, destroy it, give it away. Don’t let them make a machine out of you, get out of the system, do your thing. Don’t organize students, teachers, Negroes, organize your head. Find out where you are, what you want to do and go out and do it.”13 Guerrilla theater, unlike grassroots politics, would bring about an alternative future simply by enacting it in the present. Why waste time organizing and compromising, they asked, when it was possible to “find out . . . what you want to do and go out and do it”? For the Diggers, guerrilla theater was not, as Brustein argued, a series of meaningless gestures carried out simply for effect, but the next logical step in the search for personal and political authenticity.

As one might have guessed, the Diggers modeled their guerrilla theater, at least in part, on Antonin Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty.” According to Artaud, to be rescued “from its psychological and human stagnation,” theater must refuse to be governed by any set of preexisting texts. “We must put an end to this superstition of texts and written poetry,” he explained. Artists “should be able to see that it is our veneration for what has already been done, however beautiful and valuable it may be, that petrifies us, that immobilizes us.”14 As Jacques Derrida so famously described it, the Theater of Cruelty was designed to present “an art prior to madness and the work, an art which no longer yields works, an artist’s existence which is no longer a route or an experience that gives access to something other than itself.”15 According to Artaud, the notion that theater would defer or subjugate itself to some preexisting text or language was ludicrous. The theater was to be its own concrete language, “halfway between gesture and thought,” whose only value lay “in its excruciating, magical connection with reality and with danger.”16 While the Diggers may not have adopted Artaud’s terminology, they nonetheless believed that guerrilla theater, like the Theater of Cruelty, could only ever exist prior to representation.

The form of representation that concerned the Diggers most, though, was not the theater’s re-presentation of a written text or the psychological reduction of the therapist but the forms of mechanical reproduction that would allow their actions to be diluted and assimilated by dominant culture. Guerrilla theater was “free” because it could only ever exist in its enactment; it could be neither repeated nor commodified in the form of an image. Any attempt to reproduce guerrilla theater was destined to fail, therefore, because each performance, like those of the Theater of Cruelty, could exist only once, as an original. It was this obsession with the singularity of performance that led the Diggers to refuse to act as spokesmen not only for the counterculture but for themselves as well. When questioned about their actions, each one would refer to himself either as “Emmett Grogan,” “George Metesky,” or, more simply, as “Free.”17 To provide their own names would make them both legally and authorially responsible for their actions. As Grogan told the members of SDS assembled in Michigan, “I’m not goin’ to be on the cover of Time magazine, and my picture ain’t goin’ to be on the covers of any other magazines or in any newspapers—not even in any of those so-called underground newspapers or movement periodicals. . . . I ain’t kidding! I’m not kidding you, me or anyone else about what I do to make the change that has to be made in this country of ours, here!”18

Seeing the Diggers for the first time in Michigan, Hoffman was inspired by these ideas of direct, theatrical action. Describing his encounter with Grogan, Fritsch, and Berg, Hoffman insisted that he understood just what the Diggers meant. When he returned to New York, he began calling himself a Digger. He burned money, and opened a Free Store on the Lower East Side of Manhattan with Jim Fourratt, a political activist and former student at the Actor’s Studio.19 But there was something fundamentally different about the version of guerrilla theater that Hoffman practiced, something that truly upset the Diggers. Not long after the New York Free Store opened, the Diggers contacted Hoffman and demanded that he stop using their name. Grogan even went so far as to publicly denounce Hoffman, saying that he had simply stolen and bastardized the Diggers’ ideas.20 What Grogan failed to recognize, however, was that, for Hoffman, what made guerrilla theater powerful was less its potential to bring about an alternative reality in the present than its ability to create startling, open-ended images.

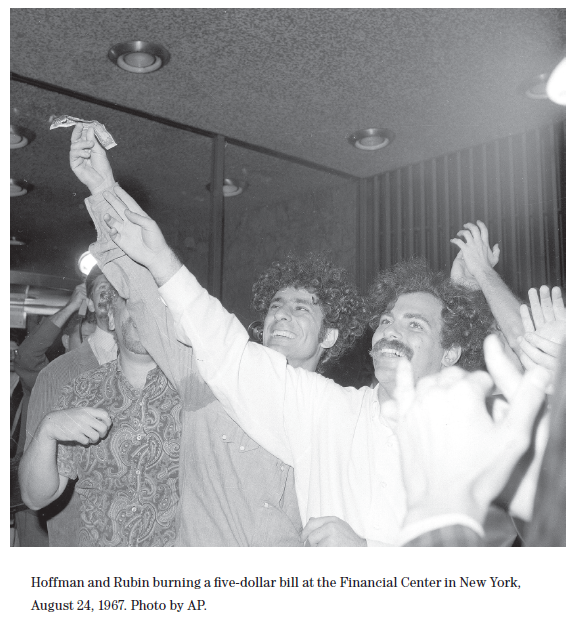

The friction between Hoffman and the Diggers seems to have begun with one incident in particular. In August of 1967 Hoffman designed a piece of guerrilla theater to be performed at the New York Stock Exchange.21 With a group of friends and reporters from local underground papers, who were there to both participate in and report on the action, Hoffman arrived at the Stock Exchange early in the morning dressed in full “hippie” regalia and requested a guided tour of the building. Security guards initially refused entry to the group, assuming, quite correctly, that they were there only to make trouble. When the guards attempted to block the door, however, Hoffman began shouting accusations of anti-Semitism, saying that their fear of hippies was only an excuse, that the real reason they were trying to turn him away was because he was Jewish. Embarrassed, the guards relented and allowed the group to pass. The guards’ suspicions were confirmed, of course, when in the middle of the tour, upon arriving at the observation deck from which visitors were able to watch the stockbrokers at work, members of Hoffman’s group pulled dollar bills from their pockets and tossed them onto the floor of the Exchange. Chaos erupted as the brokers stopped what they were doing and scrambled to pick up as many of the bills as they could. As Marty Jezer, one of the reporters in Hoffman’s group, later wrote, “The contrast between the creatively dressed hippies and the well-tailored Wall Street stockbrokers was an essential message of the demonstration. . . . Hippies throwing away money while capitalists groveled.”22

Jerry Rubin, who had met Hoffman only days before the demonstration, recalled, “Police grabbed the ten of us, dragged us down the stairs, and deposited us on Wall Street at high noon in front of astonished businessmen and hungry TV cameras. That night the attack by the hippies on the Stock Exchange was told around the world—international exposure!”23 In spite of that exposure, however, just what had happened inside the Stock Exchange was immediately shrouded in myth. No two accounts were the same. No one—including the participants—seemed to be sure how much money had been thrown, or just who had participated. When reporters asked Hoffman for his name, he told them that he was Cardinal Spellman, the Roman Catholic leader who had recently offered public support for the war in Vietnam; when asked about the number of demonstrators involved in the action, he simply said, “We don’t exist,” and burned a five-dollar bill for the camera.24 The opportunity to play games like this with reporters was just what Hoffman had hoped for in designing the action. He and Fourratt had even contacted various media outlets the previous evening and urged them to be at the Stock Exchange to witness the commotion that morning. Hoffman believed that these events, when presented in the form of a newspaper article or a story on a television newscast, would be transformed into “blank space,” one of the most useful weapons in any activist’s arsenal. Blank space, he wrote, was “a preview. . . . It is not necessary to say that we are opposed to ____. Everybody already knows. . . . We alienate people. We involve people. Attract-Repel. . . . Blank space, the interrupted statement, the unsolved puzzle, they are all involving.”25 Rather than simply telling people what to believe, actions like the one at the Stock Exchange would give them an opportunity to draw their own conclusions, to insert themselves into, or implicate themselves in the meaning of what they saw or heard. If one could use the media to broadcast those images to greater numbers, so much the better. Thus, where the Diggers looked to make themselves unrepresentable, Hoffman saw mechanical reproducibility as integral to the work of political opposition.

In part, this was because, at approximately the same time as his encounter with the Diggers in Michigan, Hoffman had begun reading the work of media theorist Marshall McLuhan. McLuhan, unlike the Diggers, praised television as the technological form that would give rise to new and radically different social forms. The way in which television presented information to the senses would drastically and irreversibly alter the forms of human interaction. Unlike the “hot” printed word, television was a “cool” medium. It offered viewers the opportunity to insert themselves into its stream of information. As a result, McLuhan argued, it would bring together vastly different cultures in a new “global village.” As he put it in perhaps his most succinct formulation, “The medium is the message”: regardless of its ostensible content, what viewers would ultimately take away from television programming was an entirely new way of engaging the world around them. Drawing on these ideas, Hoffman began to believe that media mythmaking could be used as a form of political activism. Thus, refusing to privilege the direct, personal contact that the Diggers so valued, Hoffman saw television coverage of political demonstrations as not just inevitable but valuable. Seeing viewers as active consumers of the images that entered their homes, rather than as passive receptors, allowed him to conceive of television as a potential instrument of social transformation.

At the same time, however, Hoffman’s belief in television as a revolutionary medium differed from McLuhan’s in one important respect. McLuhan believed that the social forms produced by television would be the result of a fundamental alteration of the senses: “It is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and interaction.”26 The instantaneous quality of televisual imagery would lead viewers to perceive the world in spatial rather than temporal terms, and thus to engage every facet of their lives in an altogether different way. Just how television’s potential should be used, however, McLuhan never made clear. In fact, the closest thing one finds to a prescription in Understanding Media smacks of totalitarianism: “We are certainly coming within conceivable range of a world automatically controlled to the point where we could say ‘Six hours less radio in Indonesia next week or there will be a great falling off in literary attention.’ Or, ‘We can program twenty more hours of TV in South Africa next week to cool down the tribal temperature raised by radio last week.’”27 Exposure to media could effectively “program” cultures to “keep their emotional climate stable,” he suggested, not unlike the way in which trade could be manipulated to maintain “equilibrium” in market economies. Obviously, Hoffman wanted just the opposite. It was the stable emotional climate of the United States, the “equilibrium in the commercial economies of the world,” that he found so troubling. Playing on McLuhan’s elision between two senses of the term “cool,” Hoffman wrote, “Projecting cool images is not our goal. We do not wish to project a calm secure future. We are disruption. We are hot.”28 Thus, while he looked to McLuhan’s work for the idea that television might play a role in bringing about a new “global village,” Hoffman’s idea of how television would be used to bring that village into existence differed greatly. For Hoffman, the medium and the message were far from inseparable. Although he sought to use television to broadcast his message, that message, ultimately, was a critique of the images television offered.

According to Hoffman, televisual images of the counterculture would never revolutionize society by “cooling off” a potentially dangerous situation. Rather, he argued that they would work by establishing a figure-ground relationship with other images on TV. As he put it, “It’s only when you establish a figure-ground relationship that you can convey information.”29 Footage of “monkey theater,” as he came to call his own version of guerrilla theater, would necessarily interact with, and stand out against, the background formed by more predictable scenes. If these images were outrageous enough, Hoffman believed, viewers would be unable to ignore or dismiss them, regardless of what commentary might be offered to frame or explain them. For this reason, he considered nightly news coverage of monkey theater to be something akin to an “advertisement for the revolution.” Images depicting hippies tossing money onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange would convey information much like the most persuasive images on television: commercials. Discussing the news program Meet the Press, Hoffman wrote, “What happens at the end of the program? Do you think any one of the millions of people watching the show switched from being a liberal to a conservative or vice versa? I doubt it. One thing is certain, though . . . a lot of people are going to buy that fucking soap or whatever else they were pushing in the commercial.”30

Advertisements were figures standing out from the ground that was the regularly scheduled program. They were designed to be quick, to the point, and to capture the viewer’s imagination. To function like an advertisement emerging from the middle of a newscast, therefore, protestors would have to distance themselves from any form of rational debate. Engaging in calm, orderly discussions about substantive issues was the manner of politicians, and, not coincidentally, of organizations like SDS. To Hoffman, any attempt to achieve political change in this fashion seemed doomed to failure: even if one managed to be included in nightly news broadcasts, the chances that what one said would change anyone’s mind were slim. No one “switched from being a liberal to a conservative or vice versa” after watching Meet the Press. Showing, for Hoffman, was completely different from saying—but not in the way that the Diggers had insisted. To be effective, guerrilla theater had to be flattened out, treated, quite literally, as an image: “What does free speech mean to you? To me it is an image like all things.”31 Attention to the form of one’s actions was necessary not because those actions had the potential to bring about a new reality, or because one wanted to “speak truth to power,” but because political opposition had become inextricable from practices and modes of representation. For this reason, monkey theater would assume a very specific form. After all, the actions of private citizens only received national attention when they were in some way sensational. Monkey theater, then, would have to be literally spectacular. In looking to make protest newsworthy, that is, the appearance and mannerisms of those who had already been deemed newsworthy would have to be adopted. Monkey theater would have to speak reporters’ language. As Pierre Bourdieu would argue thirty years later, “You have to produce demonstrations for television so that they interest television types and fit their perceptual categories.”32 Monkey theater, in other words, would have to look like a “revolution”; it would have to conform to television reporters’ conception of an uprising.

Following the events staged at the Stock Exchange, Rubin, captivated by Hoffman’s media savvy, invited him to aid in the organization of an upcoming demonstration sponsored by the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam (Mobe). David Dellinger, the head of the Mobe, had enlisted Rubin’s help that summer, after Rubin’s bid to be elected mayor of Berkeley, California, had failed. Although he lost the mayoral race, Rubin’s knack for publicity and his ability to appeal to young people seemed, to Dellinger, just what the Mobe needed. Dellinger was seeking to bring vast numbers of protestors to Washington, DC, in October for a national antiwar demonstration. He asked Rubin to take charge of the project, hoping that Rubin would be able to deploy the creative political tactics for which he had become known in Berkeley on a national stage. By appealing to those youths who might otherwise have been reticent to take part in one of the Mobe’s more conventional actions, Dellinger hoped to assemble the largest antiwar demonstration to date. With Hoffman and Rubin composing the script, however, what was initially conceived quite literally as the antiwar movement’s March on Washington became instead another work of monkey theater.

The event, as they saw it, might begin with a march, but that march would end south of the Potomac in a massive act of civil disobedience on the grounds of the Pentagon. Dellinger protested, explaining that authorities would simply have to block the bridge leading out of Washington and their plans would be ruined, but Rubin and Hoffman were undeterred. It was essential that the demonstration engage the Pentagon, Rubin explained, for it was “a symbol so evil that we can do anything we want and still get away with it.” Thus, “Our scenario: We threaten to close the motherfucker down. This triggers the paranoia of the Amerikan government: The Man then organizes our troops for us by denying us a place to rally and march. Thus just-another-demonstration becomes a dramatic confrontation between Freedom and Repression, and the stage is the world.”33 To announce the event, Rubin and Hoffman called an official press conference on August 28. As Rubin explained, their performance was to “grab the imagination of the world and play on appropriate paranoias,” ensuring that no one would be able to ignore or forget their threats and promises in the weeks leading up to the protest.34

They assembled an appropriate cast of characters. David Dellinger and Bob Greenblatt were there as official representatives of the Mobe. Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory was also invited, as were, Rubin recounted, “a Vietnam veteran, a priest, a housewife from Women Strike for Peace, a professor, an SDS leader,” and “Amerika’s baddest, meanest, most violent nigger—then H. Rap Brown,” who, “whether or not he even showed up at the Pentagon, would create visions of FIRE.”35 As menacing as Brown may have seemed, however, it was Hoffman who stole the show. He wore an old, unbuttoned army shirt and introduced himself as Col. Jerome Z. Wilson of the Strategic Air Command, telling reporters that he had recently deserted because of “bad vibrations.” On the day of the protest, he said, Washington’s famed cherry trees would be defoliated, the Potomac River would be dyed purple, and marijuana, which had already been surreptitiously planted on the lawn of the Pentagon, would be harvested. Moreover, he explained, as a grand finale, demonstrators would stand side by side, holding hands and chanting in a circle around the Pentagon. The importance of the circle, he explained, was that a ring of humans joining hands would cause the Pentagon to rise from the ground, and would force the evil spirits inhabiting the building to fall out. The warmongers were to be vanquished by a demonstration of countercultural “love” and “spirituality.”

Of course, Hoffman never believed that protestors would be able to levitate the Pentagon. On one hand, the claim was about numbers: the idea of the number of bodies necessary to form a circle around the Pentagon would in itself make the upcoming demonstration seem enormous. On the other hand, the exaggerated and farcical reference to a kind of mystical spirituality emblematized a number of stereotypes regarding hippies and the counterculture. Describing his motives for the claim, Hoffman wrote, “The peace movement has gone crazy and it’s about time. Our alternative fantasy will match the zaniness in Vietnam.”36 The outlandishness of this alternative fantasy would allow neither reporters nor viewers to ignore it. It would be so incredible, in fact, that it would stand in relief against the background of daily news footage from Vietnam, which, though often horrific, had become commonplace. Against this ground, Hoffman would attempt to broadcast a figure of “revolution.”

In the days following the press conference, the story of the Pentagon’s potential capture by hippies practicing a type of angrily joyful mysticism took on a life of its own. The Washington, DC, police department issued a formal statement saying that they were prepared, should the demonstration get out of hand, to use Mace to temporarily blind protestors. In response, Hoffman issued a statement of his own, claiming that hippie scientists had developed a new sex drug called Lace. “Lace is LSD combined with DMSO, a skin-penetrating agent,” he announced to the press. “When squirted on the skin or clothes, it penetrates quickly to the bloodstream, causing the subject to get sexually aroused.”37 For those who doubted his claims, Hoffman and friends staged an orgy. Reporters were told to meet at his apartment for proof of the drug’s existence. Upon their arrival, Hoffman delivered an introductory speech “full of mumbo-jumbo,” and then asked a number of “test subjects” to proceed with a “demonstration.” “The subjects shot themselves with water pistols full of purple Lace, took off their clothes, and fucked. Then they put their clothes back on, and the reporters interviewed them.”38 Within days the media was abuzz with rumors and questions about the new sex drug. As Hoffman later said, “People suspected the Lace demonstration was a put-on, but then again. . . . Hippies, drugs, orgies: it was perfectly believable.”39 Hoffman knew that in some sense the viewing public saw the counterculture as little more than a hypersexualized form of youthful rebelliousness. But rather than attempting to correct that impression, he seemed to delight in reinforcing it.

Not surprisingly, his willingness to enact these negative stereotypes for the mainstream press drew the ire of more than one critic. In his 1968 text The Making of a Counter Culture, Theodor Roszak lambasted Hoffman for promoting a debased version of “cultural revolution.” For Roszak, Hoffman’s association with the counterculture was nothing more than the result of a series of misunderstandings. The “true” counterculture, he believed, would never have “performed” for the media. To the contrary, for those who understood and shared the counterculture’s dissatisfaction, the media merely offered proof of the soullessness of contemporary society.

For Roszak—and, he argues, for members of the true counterculture—the media were ultimately symptomatic of the larger problem facing America in the mid-twentieth century, the problem of “technocratic” thought. The flood of information that confronted people in their daily lives had qualitatively transformed experience. Individuals had been subordinated to technology, categorized as sets of facts subject to specialized knowledge, and thus alienated from themselves: “In the technocracy everything aspires to become purely technical, the subject of expert attention.”40 Individual desires had been commodified and subsumed within the technocratic social order. Life, as a result, had come to seem like a parody of itself. For the first time in history it had become possible for people to believe that “real sex . . . is something that goes with the best scotch, twenty-seven-dollar sunglasses, and platinum-tipped shoelaces.”41 At the same time, though, this technocratic society carried within it the means of its own dissolution. The advanced education necessary to produce specialists in various technical fields had also equipped students with the ability to think critically about the sociohistorical conditions that necessitated such specialized knowledge. Recognizing the relationship between this highly specific knowledge, on one hand, and their own intense psychic and social alienation on the other, many of those who were to become the technocracy’s future leaders began to rebel. According to Roszak, therefore, if one hoped to understand the counterculture it was essential to understand the work of Herbert Marcuse, for it was precisely this psychosocial alienation that Marcuse had, in the mid-1950s, so cogently diagnosed.

In Eros and Civilization, first published in 1955, Marcuse had argued that the solution to the alienation of the individual was to be found in the reclamation of the state of infantile sexuality that Freud labeled “polymorphous perversity.” According to Freud, during infancy, the barriers that separate normative sexuality from perversion—the interdiction of bestiality, incest, homosexuality, and so on—are absent. The taboo that most interested Marcuse, though, was that which restricted erotic experience to the genitals. Unlike Freud, who saw this as a necessity of the individual’s biological development, Marcuse claimed that this barrier’s existence was firmly rooted in concrete historical circumstances. By condensing and restricting sexuality to the act of intercourse as such, Marcuse argued, social mandates had succeeded in relegating erotic experience to the realm of leisure. Eroticism, in other words, was transformed into something that was acceptable only at certain moments and in certain locations, an activity that could fit within the demanding schedule of the industrial worker. According to Marcuse, this particular process of socialization, necessary to reproduce the individual as a means of production, must therefore be described as “surplus repression.” That is to say, the form of repression that Freud presented as necessary to the basic development of the individual was, according to Marcuse, intimately linked to the forms of heteronomy that characterized modern capitalism. Thus, for Marcuse, the elimination of surplus repression would play an absolutely central role in the liberation of the individual. The “unrepressed development” of the erotogenic zones of the body, he argued, “would eroticize the organism to such an extent that it would counteract the desexualization of the organism required by its social utilization as an instrument of labor.”42 In Eros and Civilization, in other words, Marcuse’s concept of liberation was inseparable from a certain notion of anamnesis. It was the remembrance, or re-membrance, of the entire body as potentially erotically charged that guided his utopian project. As he put it, “if work were accompanied by a reactivation of pregenital polymorphous eroticism, it would tend to become gratifying in itself without losing its work content.”43

By extension, he also believed perversion to function as a living symbol of utopia. Appropriating Stendhal’s famous aphorism regarding the work of art, Marcuse wrote, “The perversions seem to give a promesse de bonheur greater than that of ‘normal’ sexuality. . . . The perversions . . . express rebellion against the subjugation of sexuality under the order of procreation, and against the institutions which guarantee this order.”44 The continued existence of perversions in the face of their interdiction constituted a sign of potential liberation. They “uphold sexuality as an end in itself. . . . They are a symbol of what had to be suppressed so that suppression could prevail and organize the ever more efficient domination of man and nature.”45 For Marcuse, writing in the 1950s, perversion, unlike art, seemed to suggest a form of rebellion that could not be assimilated into the dominant culture in any positive form. Where art ultimately legitimized a given social reality, true perversion was said to be capable of relating to that social reality only as a site of failure.

For Roszak, this belief in the liberating potential of Eros lay at the heart of the counterculture. These youths sought to re-eroticize the individual, and, in so doing, to free human sexuality from the demands of instrumentality. At the same time, however, this was also one of their most frequently misunderstood demands. To their elders, these longhaired, shabbily-dressed hedonists appeared to be something akin to “an invasion of centaurs,” a violently perverse “anticulture” seeking nothing other than to destroy society in the name of sensual indulgence.46 According to Roszak, the media had only further exacerbated these fears. They had reduced the counterculture to a caricature, enabling it to be assimilated as an image of the “way out”: “Dissent, the press has clearly decided, is hot copy. But if anything, the media tend to isolate the weirdest aberrations and consequently to attract to the movement many extroverted poseurs.”47 The individuals singled out by the media bore only an external resemblance to the counterculture. The “technocratic realism” of “CBSNBCABC” focused solely on appearances, and was therefore unable to make the distinction between the “true” counterculture and those “extroverted poseurs” that happened to turn up in the same places.

Not surprisingly, Hoffman was the “extroverted poseur” Roszak had in mind. By performing his “cultural revolution” for the media, Hoffman had succeeded only in promoting himself as a new form of celebrity; he represented not the counterculture but the “foulmouthed whimsy of a hip a-politics.”48 It should have shocked no one, therefore, to find Mademoiselle magazine describing Hoffman as a “new type of sex symbol,” and calling him “the Rhett Butler of the Revolution.”49 For Roszak, this would merely have confirmed the spuriousness of Hoffman’s form of opposition. The “true” counterculture, Roszak believed, sought to redefine sexuality through the liberation of Eros. Thus the men of the “real” counterculture would never have staged orgies for reporters, and would never have been considered “sex symbols.” In fact, as Roszak argued, they had cultivated a certain “feminine softness.” Where the Diggers called upon misogynistic and homophobic rhetoric in hopes of avoiding the powerlessness that plagued traditional organizations like SDS, the men of the “true” counterculture, Roszak believed, were markedly unmasculine. And for this they were to be celebrated. “It is the occasion of endless satire on the part of critics,” he wrote, “but the style is clearly a deliberate effort on the part of the young to undercut the crude and compulsive he-manliness of American political life. While this generous and gentle eroticism is available to us, we would do well to respect it, instead of ridiculing it.”50 The goal of the liberation of Eros was not the intensification of sexuality but its fundamental transformation. Machismo, therefore, was to be abandoned for “true” eroticism. For Roszak, this is what separated the counterculture’s version of “free love” from the debased sexuality of the technocracy. But because technocratic knowledge dealt only in surfaces, this was for many one of the most difficult aspects of the counterculture to comprehend. The media could thus present the counterculture as simultaneously violently aggressive and hopelessly ineffectual, or, to put it another way, threateningly hypermasculine and laughably effeminate. Nevertheless, for Roszak, it was this essential “softness” that distinguished the authentic counterculture from someone like Hoffman, whose testosterone-driven, egomaniacal self-promotion merely played upon the public’s misconceptions for personal gain. Yet, to many Americans, Hoffman’s sexuality, not to mention that of the Diggers, seemed just as ambiguous as that of any other member of the counterculture.51

In his book Homosexuality in Cold War America, Robert Corber explains this difficulty not in terms of a utopian eroticism but as a function of the postwar crisis in American masculinity. In the 1950s, he explains, masculinity had in many ways come to be equated with supportiveness and domesticity rather than ingenuity and independence. In the years following World War II, American men had begun to define themselves through patterns of consumption—something once expected only of women—rather than professional achievements. At the same time, however, to reach “the levels of consumption necessary for sustaining economic growth,” forms of homosocial bonding had to be discouraged.52 Thus, Corber writes, those most likely to be seen as “objects of suspicion in the intensely homophobic climate of the postwar period were not those who participated actively in the domestic sphere or who submitted passively to corporate structures—modes of behavior that in another context might have marked them as insufficiently masculine—but those who refused to settle down and raise a family.”53

Those who rebelled against the restraint of consumer society, and were thus depicted as somehow more effeminate, had not cultivated a “feminine softness”; rather, they had deployed a regressive, outmoded form of masculinity. Sexuality, therefore, had not been transformed in Roszak’s account of the counterculture so much as it had been romanticized, fetishized as the source of liberation. The sexuality of Roszak’s counterculture appeared ambiguous not because it was a living symbol of liberation but because it was, in the end, a product of nostalgia.

Hoffman’s Lace “demonstration” thus drew self-consciously not only on popular stereotypes of the counterculture but also on the myth of “free love” as liberation propagated by “proponents” of the counterculture like Roszak. Hoffman embodied the most hackneyed clichés about the counterculture, drawing attention to and satirizing those clichés while using them to raise the dramatic stakes in the coming showdown between protestors and the United States government. Once again, as Rubin explained, these publicity stunts were about turning “just-another-demonstration” into “a dramatic confrontation between Freedom and Repression.” And in this sense, they got precisely the results they had wanted. As much as Hoffman’s imagistic treatment of the counterculture unnerved Roszak, his antics were even more disturbing to those in power, though obviously for different reasons. In the weeks following the press conference and the Lace “demonstration,” a number of government officials, including President Lyndon Johnson, became increasingly anxious about Hoffman’s claim that demonstrators would levitate the Pentagon. Their concern, of course, was not that a circle of chanting human beings might actually raise the building. If demonstrators were to circle the Pentagon, however, it would render the building effectively inaccessible, either bringing all operations taking place inside virtually to a halt, or compelling officials to forcibly remove protestors from the grounds. News of the Johnson administration governing by force at home while attempting to spread “peace” and protect “democracy” in Southeast Asia would obviously have been a political disaster. In a battle of images, in other words, Hoffman and Rubin had backed the government into a corner. The tension would be defused only in the final days leading up to the demonstration, when, with Johnson threatening to deny march permits and to turn away all buses headed for the District of Columbia that weekend, Dellinger and other Mobe leaders were forced to negotiate.

To be sure, Johnson was not the only one pressuring Dellinger to concede. Leaders of other antiwar groups, such as SDS, Women Strike for Peace, and the Socialist Workers Party, along with activist-celebrities such as Dr. Benjamin Spock, threatened to withdraw their support from the march if Dellinger could not convince Rubin and Hoffman to soften their rhetoric. But in spite of these last-minute efforts to alter the demonstration’s tone, it was too late. Hoffman and Rubin had already captured the imagination of America’s youth, and thousands flocked to Washington for what the two “organizers” had promised would be the most exciting demonstration in recent memory. As Norman Mailer wrote in his novel about the Pentagon protests, The Armies of the Night, “Tens of thousands travel[ed] hundreds of miles to attend a symbolic battle.”54 Mailer described/romanticized “a hippie got up like Batman,” another “dressed like Charles Chaplin,” and still others dressed as “Martians and Moonmen and a knight unhorsed.” Onlookers were thus treated to a scene that “fulfilled to the hilt our General’s oldest idea of war which is that every man should dress as he pleases if he is going into battle, for that is his right, and variety never hurts the zest of the hardiest workers in every battalion.” Their props and costumes, shabby as they may have been, demonstrated that “the aesthetic at last was in the politics.”55

Hoffman’s and Rubin’s media tactics had mobilized the most creative elements of the counterculture. For Hoffman, however, placing “the aesthetic in the politics” was more than a matter of propaganda. Rather, the image itself had become the primary site of battle. The distinction between the political and the aesthetic could no longer be taken for granted; calls for “real” politics had to be taken with a grain of salt. Hoffman rather cleverly illustrated this point when he urged his fellow activists, “You are the Revolution. Do your thing. . . . Pratice. Rehearsals come after the act. Act. Act. One practices by acting. . . . There are no rules, only images.”56 This passage, which begins with what seems to be yet another Digger-inspired argument for the transformative power of guerrilla theater, concludes by alerting the reader to the doubled meanings inherent in many of its key terms. If, as Hoffman claimed, there were only images—if he wrote these thoughts only because, as he put it, he had “no idea how to make a movie”57—then what did it mean to speak of revolution as practice, or of practice as “acting”? It was precisely this play that guided Hoffman and Rubin in planning the Pentagon action and, later, their most famous (non)demonstration, which took place in Chicago during the Democratic National Convention in the summer of 1968.

Following the Pentagon action, a number of organizations began preparations for a series of massive demonstrations surrounding the Democratic National Convention. The Mobe, for example, announced that it would organize and sponsor a large-scale march that would conclude at the Chicago amphitheater where the convention was to be held. In light of the difficulties surrounding the demonstration in Washington, though, the Mobe’s leaders were no longer so eager to capitalize on Rubin’s and Hoffman’s appeal. Likewise, the two mythmakers were pleased to sever their connections with the Mobe. Emboldened by their success in drawing so many participants to the Pentagon, they believed that, freed from the constraints imposed by the more conservative antiwar organizations, they might (dis)organize a truly grand work of monkey theater. With the help of a number of friends and fellow activists, they began developing plans for a large concert similar to the Monterey Pop Festival. A concert staged in spatial and aesthetic opposition to the Democratic National Convention, they believed, would allow them to provide a counterpoint not only to the official proceedings of the Democratic Party but also to the more staid, traditional demonstrations of groups like the Mobe. The concert would be more than a protest; it would be promoted as a celebration, an affirmation of life in the face of the “Party of Death.” Hoffman and Rubin trusted that large numbers of young people could be convinced to make the trip to Chicago to hear their favorite bands, and the news that tens of thousands had gathered in opposition to the prowar Democratic Party would energize and mobilize an entirely new constituency, one seeking an alternative to politics-as-usual. At a New Year’s Eve party in 1967, Rubin, Hoffman, Fourratt, Nancy Kurshan, Paul Krassner, and Hoffman’s wife, Anita, began to discuss plans not so much for the concert itself but for creating the festival as a media phenomenon. In hopes of maximizing their exposure, the group concocted a mock organization to serve as the event’s mythical sponsor. Punning on the basic idea of an international youth festival, Anita Hoffman proposed calling this pseudo-organization the Youth International Party. With such an official-sounding title, she explained, the media would have virtually no choice but to take the group seriously. Furthermore, those who were in the know, so to speak, would get the joke, recognizing that “party” could be understood in more ways than one. To their supporters, therefore, they should be known not as the YIP but as “Yippie!”

As always, to rally support they would need the media’s help. Hoffman later explained that when it came to publicizing the Youth International Party, “Reporters would play their preconceived roles: ‘What is the difference between a hippie and a Yippie?’ A hundred different answers would fly out, forcing the reporter to make up his own answer; to distort.”58 In March, the Yippies held their first official press conference to announce their plans for the “Festival of Life.” The Mobe had already made public its own plans to hold peaceful protests in Chicago, but the Yippies promised to go much further. They vowed to present America with a vision of “the politics of ecstasy.” America’s youth, they claimed, would be transformed, radicalized by the Youth International Party’s message. Everyone under the age of thirty would “rise up and abandon the creeping meatball.”59 Just what this meant was anything but obvious, and for the Yippies, that was precisely the point. “Yippie!” would become news not by issuing statements of theoretical or tactical precision but by playing on Americans’ fears and preconceived notions regarding the emergent youth culture. “The straight press thought that ‘creeping meatball’ meant Lyndon Baines Johnson and that we wanted to throw him out of office,” Rubin wrote. “We just laughed. . . . Where would we be without LBJ?”60 In fact, “rise up and abandon the creeping meatball” was, in itself, meaningless. It was nothing more than a waggish turn of phrase, an empty signifier onto which each listener could project his or her own interpretation: “Everybody has his own creeping meatball—grades, debts, pimples. Yippies are a participatory movement. There are no ideological requirements to be a Yippie. . . . Yippie is just an excuse to rebel.”61 To further agitate and intrigue the public, Rubin and Hoffman announced that the group would stage an enormous, intentionally ill-defined “YIP-in” at Grand Central Station less than one week later.

The publicity worked. On the night of the YIP-in, nearly three thousand young men and women filled Grand Central’s main terminal, blocking nearly all routes of passage. It was, as YIP’s name suggested, a party: balloons floated through the air, and people danced and shared popcorn with bemused commuters. Not unlike tossing dollar bills onto the floor of the New York Stock Exchange, the YIP-in caricatured the seemingly obvious distinction between generations and cultures. And for its participants, whether or not they understood this, the event seemed a success. Everyone appeared to be enjoying themselves. The tone of the evening changed in an instant, however, when the police charged into the crowd swinging nightsticks. The officers claimed to be pursuing members of an anarchist group known as the Motherfuckers, who had begun dismantling the large clock atop the information booth. Yet in spite of their stated intentions, the scene was nothing less than a police riot. No attempt was made to clear the station in any systematic fashion; participants were beaten with billy clubs; and Don McNeill, a reporter covering the YIP-in for the Village Voice, was thrown through a plate glass window.62 After more than an hour of brutal violence, the officers retreated, leaving nearly a thousand revelers behind. Clearing the station, it seems, was less of a priority than the assertion of police authority. The next day, when many expected the Yippies to hide in embarrassment, Hoffman and Rubin issued an “official” statement to the press accusing the police of “animalistic behavior,” “brutality,” and “creephood.”63 The Yippies, that is, responded to the officers’ posturing with their own. As Brustein would suggest two years later, “violent official retaliation” had become, like the Yippies’ version of “revolution,” another form of theater.64

After the YIP-in, Hoffman, Rubin, Fouratt, Krassner, and Marshall Bloom, head of the Liberation News Service (LNS), flew to Chicago to discuss the logistics of the upcoming demonstrations with representatives of the local and national antiwar movements. First they attended an early planning session sponsored by the Mobe, interrupting the scheduled speakers to expound upon, among other things, the evils of pay toilets. After the Mobe’s meeting, the Yippies met with a number of Chicago-based activists to discuss different ways of publicizing the Festival of Life both locally and nationally. Local activists were anxious about the Yippies’ plans, fearing retaliation from the police and Chicago mayor Richard Daley. To assuage these fears, Rubin and Hoffman promised that they would apply for the legal permits required to hold a concert in Lincoln Park.65

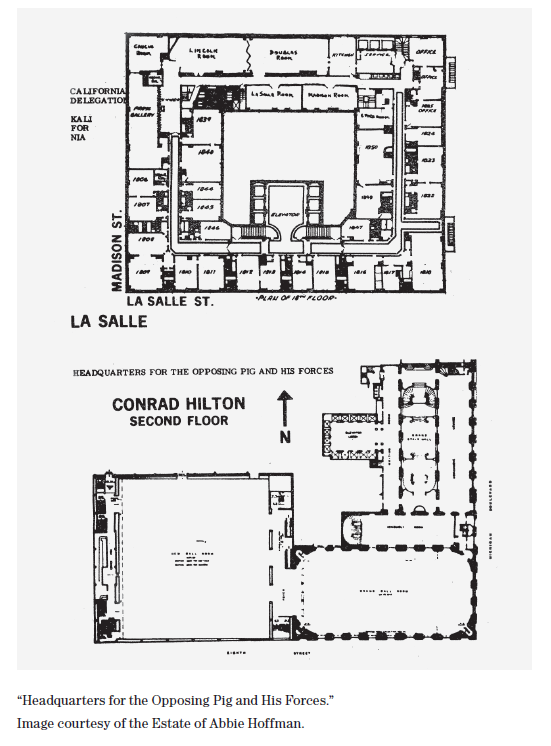

Nevertheless, while they tried to appease local organizers, the Yippies continued to use the media to antagonize the authorities and the general public. While in Chicago, Hoffman and Rubin scheduled two press conferences in which they discussed “plans” for the Festival of Life. They promised to taint Chicago’s water supply with LSD, and to send Yippie women into the convention to flirt with and drug the delegates while “hyperpotent” Yippie men seduced their wives. They told reporters that the Youth International Party would hold its own counterconvention as part of the Festival of Life, during which they would nominate a pig, to be named “Pigasus,” for president. At one press conference, Hoffman distributed a written statement declaring, “The present day politicians and their armies of automatons have selfishly robbed us of our birthright. The evilness they stand for will go unchallenged no longer. Political Pigs, your days are numbered. We are the Second American Revolution. We shall win. Yippie!”66 This statement was paired with a floor plan of the Conrad Hilton Hotel in which Democratic Party delegates and nominees would stay, labeled, “Headquarters for the Opposing Pig and His Forces.” Of course, Hoffman quipped, the Yippies would be willing to call the whole thing off if the city would simply pay them $100,000.

As with their call to “rise up and abandon the creeping meatball,” and Hoffman’s promise to levitate the Pentagon, the absurdity of the Yippies’ threats was part of the point. And although the authorities suspected the Yippies’ antics to be nothing more than a put-on, they were compelled to play the “straight man.” Whether or not they took the Yippies’ threats seriously, they feared that the rest of America would. Given the student strike at Columbia University, in which five University buildings were occupied by students and protestors for a full week in late April, and the student-led uprisings in Paris shortly thereafter, a large-scale rebellion led by American youth seemed entirely plausible. So even though the FBI and CIA knew that the Yippies’ “plan” to spike Chicago’s water supply with LSD was ludicrous, Mayor Daley was forced to station police officers at each reservoir access point all the same. This official posturing eventually turned proactive when, later in the summer, Daley issued his own threats designed not to force the Yippies to behave in a more orderly fashion but to keep demonstrators from coming to Chicago at all. Most famously, he guaranteed that Chicago police would be authorized to “shoot to kill” any demonstrators they deemed a threat to the city’s security.

Indeed, the mayor’s threats did frighten many of those who would otherwise have gathered in Chicago for the demonstrations. In “A Letter from Chicago,” distributed through LNS, Abe Peck, the editor of the Chicago Seed who had at one time identified himself as a Yippie, warned readers with a twist on Scott McKenzie’s well known lyrics: “If you’re coming to Chicago, be sure to wear some armor in your hair.” Similarly, the Berkeley Barb stated, “Flower children may be quickly ‘radicalized’ by having their heads busted by a cop’s billy club.”67 The Yippies’ provocations had apparently exhausted the patience of those for whom they purported to speak, and to many, it began to seem as if the entire project was doomed. In the months between the Grand Central YIP-In and the Festival of Life, the Yippies’ requests for legal permits were repeatedly deferred, until Hoffman and Rubin officially withdrew them. As a result, most of the bands that had agreed to participate in the Festival of Life backed out—in the end folk singer Phil Ochs and the radical rock band The MC5 were the only ones willing to participate—and a number of activists who had earlier declared themselves Yippies quickly turned on Hoffman and Rubin personally. Dissenters argued, in what would become a familiar refrain, that the Yippie “leaders” had become more concerned with their own celebrity than with real social change.

Three years later, New York Newsreel’s Norman Fruchter reiterated this sense of frustration with the Yippies in an essay “Games in the Arena: Movement Propaganda and the Culture of the Spectacle.” According to Fruchter, the Yippies’ ultimate downfall lay in their willingness to engage the media on its own terms. In their attempts to use the media as a revolutionary tool, he argued, Hoffman and Rubin had ultimately betrayed the youth culture for which they claimed to speak. “By using youth-culture’s surfaces as values and as challenges,” he wrote, they “reduced the entire content of youth-culture for convenient assimilation by the spectacle.”68 The Yippies’ celebrity was thus counterproductive, for ultimately their public personae served only to discredit the causes they claimed to advocate. By “defining the mass media as a Yippie tool of communication and politicization of unorganized youth,” Fruchter argued, “the Yippie leadership was able to singlemindedly exploit its individual relationship with the mass media—indeed, it defined its assimilation by the spectacle as its primary political work.”69 True opposition, on the other hand, could exist only in its enactment. As Fruchter put it, “Individual spokesmen, however sensitive, could never have performed or represented” the values of the American youth culture, “for [those values] were embodied in collective work.”70 When they willingly played the role of the youth culture’s “leaders,” Hoffman and Rubin effectively sold out their own movement. Whether they intended to or not, the Yippies had reduced the youth culture “on the stage of the spectacle, and therefore in the mass mind of the national audience, to its lowest common denominator surfaces.”71

For Fruchter, not unlike Brustein, the Yippies were not the only ones to make this fatal mistake. In fact, they were one of many organizations that had been defeated by their own naïve faith in a new technology. According to Fruchter, any attempt to use the mass media to build a revolutionary movement in the United States would be doomed to failure. “The spectacle is not subversive,” he wrote, “it is the negation of subversion.” Presented as reality tout court, the spectacle “is the most insidious and perfect employer of ideology, because it has achieved a total ideological construct which claims absolute neutrality for itself because it represents reality. The problem of participation in the spectacle is the problem of finding the terms to struggle against a total ideological construct from within that construct, when that construct represents itself as reality.”72 The media, in spite of its claims to an exhaustive realism, would never present the truth of political opposition. In representing activists and activism, the media only domesticated them, made them consumable. The mass media stripped protests and demonstrations of any real political import, and offered up their surfaces as truths.

What makes Fruchter’s argument particularly interesting is that, when placed next to Brustein’s complaints regarding the theatricality of calls for “revolution,” the two authors effectively restate the dialectic of “repressive tolerance” outlined in 1966 by a frustrated Herbert Marcuse. As I have already explained, in the mid-1960s, Marcuse argued repeatedly that in the context of American liberal democracy, “tolerance” had become a parody of itself. The mass media, lauded by some for its democratic potential, had only served to negate political dissent. The press no longer acted as a check on state power but instead justified the status quo. In the papers, on the radio, or in television news broadcasts, one could say virtually anything one wanted because nothing was at stake. To use Hoffman’s own example, no one would switch from being a Democrat to a Republican after watching Meet the Press, nor would they suddenly be convinced of the moral correctness of pacifism after hearing the arguments of an antiwar spokesman such as David Dellinger. Value judgments, as Marcuse explained, had been placed on all positions prior to their articulation. Given this unspoken bias, the apparent objectivity of the media had become an offense “against humanity and truth.”73 It had robbed individual acts and pronouncements of their political significance. One could “speak truth to power,” but nothing would come of it, for a “spurious” tolerance had separated the public from its true “political existence.” The normative order had colonized any and all opposition so thoroughly that particular grievances had been rendered largely meaningless. As a result, individuals had taken refuge in “the satisfactions of private and personal rebellion.”74 They had adopted the language of self-fulfillment, identifying in the process with an inherently hostile social order. In this context, nonconformity and “letting go,” no matter how shocking they appeared to some, nevertheless left “the real engines of repression in the society entirely intact.”75 The apparently limitless tolerance for political disagreement was, in other words, simply another aspect of the more general phenomenon Marcuse described in One-Dimensional Man as “repressive desublimation” (a concept, it is worth noting, that essentially reversed the theory of perversion presented in Eros and Civilization). Thus, whether in the form of political speech or personal behavior, rebellion had been turned against itself; it had become the ultimate in conformity. And for Fruchter and Brustein, this is precisely what groups like the Yippies had failed to recognize. By treating the youth culture’s appearance as a value in itself, Hoffman and Rubin had not rebelled so much as they had embodied a compromised, spectacular image of “rebellion.”

To be sure, in arguing that the values of the youth culture were only ever accessible through their enactment, rather than their representation, Fruchter appears far more optimistic than Marcuse. For Fruchter, “real” progress could be made only through “real” personal and political work. Thus, he believed, the true value of the youth culture lay in its commitment to locating a form of personal authenticity without mistaking that authenticity for an end in itself. Similarly, in the case of the student New Left, victories, no matter how small, resulted not from outrageous pronouncements made to the media regarding the size or effectiveness of a given demonstration, but from the difficult work of grassroots political organization. The spectacle did not necessarily preclude these forms of personal and political labor, but in its equation of images and reality it had made them far more difficult. In spite of what Marcuse depicted as a set of virtually ineluctable historical limitations, it was still possible, and necessary, Fruchter believed, to envision and work toward substantive social change. And, like Brustein, Fruchter insisted that the way forward lay in “writing off” calls for “revolution” as little more than theater or spectacle, and rededicating oneself to the “real” task of grassroots organization. For the Yippies, however, the work of “real” organizing was no more immune to its own domestication than any other form of theater or politics: this was one of the points they sought to make with the Festival of Life. To their dismay, however, the Democratic Party seemed to have beaten them to the punch.

First, Lyndon Johnson announced in a televised speech on March 31 that he would not seek reelection. “He dropped out,” Hoffman punned. “Remember a guy named Lyndon Johnson? He was so predictable when Yippie! began. And then pow! He really fucked us. He did the one thing no one had counted on. . . . ‘My God,’ we exclaimed. ‘Lyndon is out-flanking us on our hippie side.’”76 While the Yippies claimed to be bemused by Johnson’s withdrawal, those involved with more traditional antiwar organizations were devastated. Certainly, there were those who saw Johnson’s abdication as a victory; after all, one of the major factors in his decision had been the domestic unrest fomented largely by antiwar activists. Many more, though, were simply stunned. On one hand, Johnson’s resignation had been coupled with an announcement that, in the wake of the Tet Offensive, the United States would soon deploy over 13,000 more troops to Vietnam. His announcement could in no way be interpreted as the beginning of the end of the war. Moreover, by recusing himself, Johnson robbed the antiwar movement of one of its most potent symbols. Activist Sam Brown recalls feeling that, though Johnson’s withdrawal may have seemed a success to some, “emotionally, it was like, ‘Oh my God. . . . We had this guy that we could point a finger at, and now it’s more diffuse, it’s impossible to get a handle on it, you can’t see it anymore.’”77

Of course, the pressure exerted by antiwar activists was only part of the reason for Johnson’s withdrawal. More than the activists themselves, Johnson had begun to fear the potential opposition of candidates who might capture the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination by running on an antiwar platform. Apparently it was not America’s disaffected youths that Johnson feared but the possibility of their incorporation within the Democratic Party. Eugene McCarthy’s candidacy offered the first indication of this. McCarthy drew support from a number of peace activists, many of whom were willing to cut their hair, shave, and change their style of dress—to “Go Clean for Gene,” as one of his campaign slogans urged—to legitimize his candidacy. McCarthy’s advisers feared that the image of an antiwar candidate endorsed by unkempt, untamed “hippies” would make it difficult to be taken seriously, and the activists who supported him, willing to do whatever was necessary to end the war, complied. But no matter how “clean” his supporters were, McCarthy’s campaign was never really taken seriously—insofar as a “serious” candidate is believed to be capable of winning—even by McCarthy himself. His hope in running, he explained, was merely to “build up enough pressure to force a change in policy.”78 Winning the Democratic Party nomination simply seemed unrealistic. To his surprise, however, voters responded favorably to the idea of an antiwar candidate, awarding him 42 percent of the votes cast in the New Hampshire Democratic primary. Many began to feel that if a peace candidate could fare so well in New Hampshire, a notoriously hawkish state, a candidate running on an antiwar platform truly could win the Democratic nomination. McCarthy, however, was still not perceived as the “right” candidate.

The antiwar candidacy that presented Johnson, and, oddly enough, the Yippies, with the most serious threat was that of Robert F. Kennedy, who began preparing to oppose Johnson early in 1968. One of Kennedy’s first steps in plotting his campaign was to meet with prominent members of the antiwar movement. In January, Kennedy and his staff conferred with SDS leaders Tom Hayden and Carl Oglesby, asking them if they believed that Kennedy could secure the vote of the student antiwar movement. Far more optimistic about Kennedy’s chances as a candidate than McCarthy, Oglesby told them that he would do his “damnedest, personally, to bring them in.”79 Virtually everything that McCarthy seemed to lack as a candidate, Kennedy possessed. Good-looking, charismatic, and the brother of one of the most popular presidents of the twentieth century, Kennedy appeared almost unbeatable. And when he officially announced his candidacy on March 16, it was a significant blow not only to Lyndon Johnson but also to the more radical members of the New Left. Battles were waged within movements such as SDS and the Mobe. Members concerned with doctrinal purity squared off against those who believed that the possibility of bringing an end to the war in Vietnam justified their participation in the two-party system of American politics. As Oglesby recalls, “To me there was no cooptation about it. If anyone was getting coopted, it was the Democratic Party. The movement was coopting the Democratic Party.”80

Much as this would have seemed to prove the Yippies’ point about the state of oppositional politics, it also presented a significant challenge to the Festival of Life. McCarthy “wasn’t much,” Hoffman explained. “One could secretly cheer for him the way you cheer for the Mets. It’s easy, knowing he can never win.” Kennedy, however, seemed just as adept at using the media and speaking to the youth of America as the Yippies. He was a “direct challenge . . . to the charisma of Yippie! Come on, Bobby said, join the mystery battle against the television machine. Participation mystique. Theater-in-the-streets. He played it to the hilt. And what was worse, Bobby had the money and power to build the stage. We had to steal ours. It was no contest. . . . When young longhairs told you how they’d heard that Bobby turned on, you knew Yippie! was really in trouble.”81 The Democrats had stolen the Yippies’ thunder. “We took to drinking and praying for LBJ to strike back,” Hoffman wrote, “but he kept melting. Then Hubert came along with the ‘Politics of Joy’ and Yippie! passed into a state of catatonia which resulted in near permanent brain damage.”82 Though Kennedy’s candidacy confirmed the party’s ability to annex the antiwar movement, if the Yippies hoped to pull off the Festival of Life, what they needed most was not to be proven correct, but theater.

Hoffman’s problem was solved, to put it rather crudely, on June 5, when Kennedy, just after his victory in the California primary, was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan, an event that, like the assassination of his brother John, was its own sort of media event. Following on the heels of the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr., for many members of the student New Left Kennedy’s death signified American society’s intransigence toward any version of reformist politics. Within SDS, Kennedy’s assassination set off a chain of events that ultimately led to the organization’s reformulation as the Revolutionary Youth Movement, and finally, Weatherman.83 As historian Tom Wells writes, SDS’s annual convention in June became “a time for determining who had the mettle for battle and who didn’t.” For example, when asked if she was a socialist, future Weatherleader Bernardine Dohrn bristled at the use of such a demure descriptor. “I consider myself,” she declared, “a revolutionary communist.”84

In the July 7 issue of the Realist, the satirical newspaper edited by Paul Krassner, Hoffman followed suit, in a sense. Describing Kennedy’s assassination, he wrote, “The United States political system was proving more insane than Yippie! Reality and unreality had in six months switched sides. . . . How could we pull our pants down? America was already naked.”85 Nevertheless, he explained, in the wake of these events the Festival of Life was more important than ever. Kennedy’s assassination had essentially righted the Democrats’ ship. No longer threatened by the challenge of a truly electable antiwar candidate, Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, who privately opposed the war but refused to do so in public, had all but won the official nomination. It would be a mistake for demonstrators and partiers to shy away from Chicago because the Democratic Party was, in Hoffman’s words, “back to power politics, the politics of big city machines and back-room deals. The Democrats had finally got their thing together by hook or crook and there it was for all to see—fat, ugly, and full of shit.”86

Seeking to capitalize on the opportunity afforded by Kennedy’s death, Hoffman distanced himself from the more outlandish rhetoric of his earlier statements, returning to the language of the Diggers’ guerrilla theater. “What we need now,” he told readers,

is the direct opposite approach to the one we began with. We must sacrifice suggestion for a greater degree of precision. We need a reality in the face of the American political myth. We have to kill Yippie! and still bring huge numbers to Chicago. . . . We will in Chicago begin the task of building Free America on the ashes of the old and from the inside out. . . . Do not come prepared to sit and watch and be fed and cared for. It just won’t happen that way. It is time to become a life-actor. The days of the audience died with the old America. If you don’t have a thing to do, stay home, you’ll only get in the way.87

The “reality” to which Hoffman alludes in this passage certainly sounds like the reality of ticketless theater. The goal, he suggested, was not to expose the truth of the Democratic Party—the Democrats had already done that themselves—but to create a new reality, to present America with a vision of an alternative future. In his biography of Hoffman, Jonah Raskin cites this passage as an indication that the assassination of Robert Kennedy marked a turning point in Hoffman’s political strategies and persona. “He didn’t feel like ‘Dwight Eisenhower on an acid trip’ anymore,” Raskin writes. Instead, he had become “the Lenin of the Flower Children.”88 According to Raskin, Kennedy’s assassination turned Hoffman from mythmaker to revolutionary. Having been out-spectacled by the Democratic Party, Hoffman placed his put-ons and media tactics to the side in a sincere attempt to bridge the gap between the hippie counterculture and the New Left. As Hoffman put it, “The radical will say to the hippie: ‘Get together and fight, you are getting the shit kicked out of you.’ The hippie will say to the radical: ‘Your protest is so narrow, your rhetoric so boring, your ideological power plays so old-fashioned.’” Nevertheless, each one could enlighten the other, “and Chicago—like the Pentagon demonstration before it—might well offer the medium to put forth that message.”89 In the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, Raskin argues, the Festival of Life was no longer about imagery but about bringing America’s oppositional youth cultures together as a unified movement.

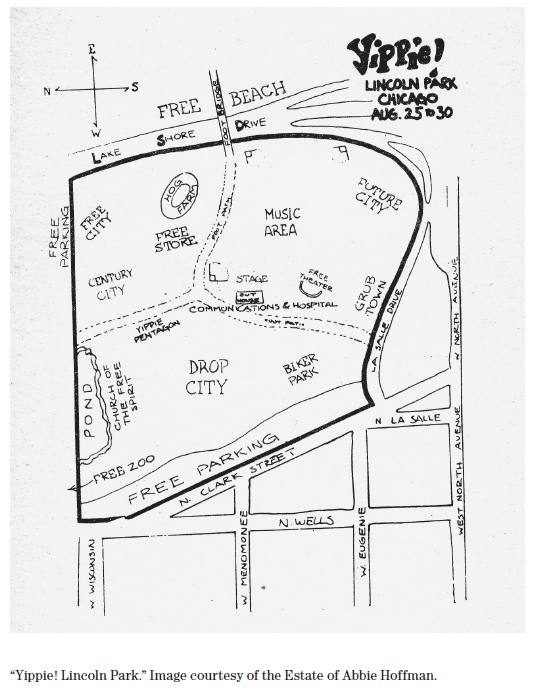

To take this supposed political transformation seriously, however, one must ultimately take Hoffman at his word. This, as it should by now be clear, was always risky. Shortly after “The Yippies Are Going to Chicago” appeared in the Realist, Hoffman and Krassner flew to Chicago in a last-ditch effort to obtain the necessary legal permits for the Festival of Life. Having agreed to meet privately with Yippie representatives, deputy mayor David Stahl asked what, precisely, the Festival of Life would involve. “I dunno,” Hoffman replied, “but whatever it is, it’ll be designed to, uh, bring down the Democratic Party.”90 The Yippies had hardly put aside their hoaxes and put-ons. Hoffman’s newfound sincerity, it seems, was itself little more than a ruse. Stahl, though, took Hoffman quite seriously, and for the last time denied the Yippies’ request for a permit. Following the meeting, Stahl even composed a memo to city officials, warning that the Yippies would “try to involve their supporters in a revolution along the lines of the Berkeley and Paris incidents.”91 In response to Stahl’s rejection, Hoffman held yet another press conference in which he offered a highly detailed schedule for the week of the convention. He promised that protestors would seize Chicago’s Lincoln Park—which would, he told them, be officially renamed “Che Guevara National Park”—and camp out there throughout the convention. He then showed reporters a map that divided the park into areas with names like “Future City,” “Free City,” “Grub Town,” and “Biker Park,” and set aside space for a Free Store, a Church of the Free Spirit, a Free Theater, a hospital, and, most importantly, a Yippie Pentagon.