3. “ERECT . . . STRONG . . . RESILIENT AND FIRM”

Eldridge Cleaver and the Performance of “Black” Liberation

AS THE PREVIOUS TWO CHAPTERS SHOW, FOR MANY IN THE LATE 1960s the visual form of political resistance was the focus of a great deal of thought and experimentation. Yet one might say that, in the cases of the counterculture and the gay liberation movement, this is understandable. Each group, after all, was faced from the beginning with the task of determining just how to present itself to the world in terms of a collective identity. In this final chapter, therefore, I would like to offer one last case study examining the political persona of one of the more consistently vilified characters of the late 1960s, Eldridge Cleaver. As Herbert Marcuse’s admiration for the civil rights and Black Power movements made clear, for many in the 1960s, questions of visual form in relation to racial politics seemed pointless, if not wholly inappropriate. Racial difference, they thought, was simply self-evident. This makes Cleaver, and in many ways the Black Power movement more generally, a particularly interesting subject of investigation.

Due to his willingness to equate the struggle for black liberation with the effort to reclaim a full black masculinity, Cleaver has been dismissed repeatedly as an example of the most misguided, even regressive, form of identity politics. For authors such as Michelle Wallace, Robin Morgan, Kobena Mercer, Isaac Julien, Leerom Medovoi, and others, more people were hurt than helped by Cleaver’s brand of racial antagonism. In spite of his critics’ easily understandable frustration, however, it seems only logical at this point to ask if there could have been something more to Cleaver’s “adoration of his genitals,” as Wallace has put it, than the mere internalization of a stereotypical masculinity. Is it possible to read in his performance of this persona not a naïve or wrongheaded version of identity politics but a critical and self-conscious engagement with the forms of masculinity that Wallace and others have found so detestable? To reassess the potential value of Cleaver’s political career, I want to look closely at his enactment of a violent, “supermasculine” version of black liberation, from his attack on novelist James Baldwin in the essay “Notes on a Native Son” to his threat to kick California State superintendent of public instruction Max Rafferty’s ass. In the process, I will place Cleaver’s outrageous pronouncements alongside both the activities and ideologies of the Black Panther Party, paying particular attention to the actions and writings of party founder Huey P. Newton, who, in spite of his eagerness to enlist Cleaver as a Panther in the late 1960s, repeatedly denounced him just a few years later. I will also revisit the work of more recent authors such as Wallace, Mercer, Julien, and others. By placing these writings next to the acts they describe and/or deride, it is possible to interrogate not only the “masculinist” version of black liberation that Cleaver propagated but also the assumed historical necessity of dismissing it.

In their essay “True Confessions: A Discourse on Images of Black Male Sexuality,” cultural theorist Kobena Mercer and filmmaker Isaac Julien describe Cleaver as the proponent of a short-sighted vision of black liberation that could only have come about at the expense of women, gay men, and lesbians. They contend that Cleaver, like a number of spokesmen for Black Power, promoted a “heterosexist version of black militancy which not only authorized sexism . . . but a hidden agenda of homophobia.”1 Cleaver’s emphasis on a militant, confrontational version of racial politics “not only ignore[d] the more subtle and enduring forms of cultural resistance which have been forged in diaspora formations” but also depoliticized “‘internal’ conflicts and antagonisms, especially around gender and sexuality within black communities.”2 In contrast to Cleaver’s vision of a fully realized black masculinity, Mercer and Julien point to a series of musicians who, throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, enacted an alternative to the heterosexist model of black power, and used their celebrity to “undercut the braggadocio to make critiques of conventional models of masculinity.”3 In future attempts to comprehend the complicated sexual politics of “blackness,” they write, it will be necessary to look not to the example of preposterously macho “freedom fighters” like Cleaver but to “artists like Luther Vandross, Teddy Pendergrass and the much-maligned Michael Jackson,” and to come to terms with the “camp and crazy ‘carnivalesque’ qualities of Little Richard—the original Queen of Rock ’n’ Roll himself.” These men, Mercer and Julien explain, “disclose the ‘soft side’ of black masculinity (and this is the side we like!).”4

Valorizing the “soft side” of black masculinity in this fashion, Mercer and Julien distance their version of “black sexual politics” from one of Cleaver’s essays in particular, “Notes on a Native Son.” In that essay, cited by so many critics of Black Power’s chauvinist tendencies, Cleaver wrote that novelist James Baldwin, as a gay black intellectual, had devoted himself and his literary career to the justification of the “racial death-wish” that plagued far too many black Americans.5 “From the widespread use of cosmetics to bleach the black out of one’s skin,” Cleaver wrote, “to the extreme, resorted to by more Negroes than one might wish to believe, of undergoing nosethinning and lip-clipping operations, the racial death-wish of American Negroes” could be observed taking “its terrible toll.”6 For Cleaver, these procedures, through which black men and women imprinted upon their bodies the visual signifiers of “whiteness,” were indicative of a larger racial “power struggle” waged throughout American history. It was not any inherent quality of white skin that gave birth to this overriding disdain for nearly all things black, that is, but the historical inseparability of dark skin and servitude. Nevertheless, according to Cleaver, it would be a mistake to reduce this racial self-hatred to a matter of habituation. To the contrary, he argued, through the cunning of the “white man,” black men and women had been not simply accustomed but bred to despise the physical manifestations of their African heritage. European standards of physical beauty had been imposed and reinforced not only culturally but hereditarily: “What has been happening for the past four hundred years is that the white man, through his access to black women, has been pumping his blood and genes into the blacks, has been diluting the blood and genes of the blacks . . . and accelerating the Negroes’ racial death-wish.”7 As a result, for many blacks the thought of “two very dark Negroes mating” was anathema, for in such a case, “the children are sure to be black, and this is not desirable.”8

Carrying this logic further, Cleaver went on to assert that the historical desirability of “whiteness” colored more than just “traditional” heterosexual relationships. For anyone attracted to men, the myth that treated the social advantages attached to white masculinity as inherent virtues precluded the possibility that a nonwhite man might be found desirable. Thus, Cleaver explained, when the gay black man “takes the white man for his lover . . . he focuses on ‘whiteness’ all the love in his pent up soul and turns the razor edge of hatred against ‘blackness’—upon himself, what he is, and all those who look like him, remind him of himself.”9 Moreover, he argued, this neurosis was compounded by the inability of same-sex relationships to produce offspring. Unlike black women, who, according to this model, were mollified by the possibility of bearing their potential white lovers’ children, gay black men, Cleaver wrote, were only further maddened. “It seems that many Negro homosexuals, acquiescing in this racial death-wish, are outraged and frustrated because in their sickness they are unable to have a baby by a white man,” he wrote. “The cross they have to bear is that, already bending over and touching their toes for the white man, the fruit of their miscegenation is not the little half-white offspring of their dreams but an increase in the unwinding of their nerves.”10 That Baldwin suffered from this particular form of “racial death-wish” could be seen, Cleaver wrote, in his critique of the work of author Richard Wright. Reflecting on Wright’s work following his death in 1960, Baldwin had claimed that, in retrospect, Wright’s own belief in his social and political acumen was foolish. “In my own relations with him,” Baldwin wrote, “I was always exasperated by his notions of society, politics, and history, for they seemed to me utterly fanciful.”11 Any social or historical insights Wright’s work may have contained were mitigated by a stubborn refusal to look beyond the surfaces of his own experiences. In Wright’s novels, as in “most of the novels written by Negroes until today . . . there is a great space where sex ought to be.” What filled this space, according to Baldwin, was a “gratuitous and compulsive” violence.12 And because Wright never really examined the root of this violence, it remained untransformed, “a terrible attempt to break out of the cage in which the American imagination has imprisoned him for so long.”13

To Cleaver, who believed that of “all black American novelists” Wright displayed perhaps the most profound social and political insight, Baldwin’s critique was nothing other than “audacious madness.”14 If violence had replaced sex in Wright’s novels, it was “only because in the North American reality hate holds sway in love’s true province.”15 To offer visions of sex in a time of hatred, he wrote, would have required Wright to forsake his “rebellion” for a “lamblike submission.” Wright was never “ghost enough” (his books, as Cleaver explained in another passage, were “strongly heterosexual”) “to achieve this cruel distortion.”16 Baldwin’s essay, therefore, although ostensibly concerned with the ways in which an unexamined rage seemed to dominate Wright’s work, was in fact a moral struggle over the proper forms of black masculinity. Where Wright, not unlike Malcolm X, offered an uncompromising image of “our living black manhood,” Baldwin seemed to embody “the self-flagellating policy of Martin Luther King . . . giving out falsely the news that the Day of the Ghost has arrived.”17 Baldwin could not “confront the stud in others—except that he must either submit to it or destroy it. And he was not about to bow to a black man.”18 According to Cleaver, this was because Baldwin, like most black men and women, and particularly gay black men, had “succumbed psychologically” to the power of the white male. The only way Baldwin could free himself from this oppression, therefore, was “to embrace Africa, the land of his fathers.”19

Yet, in relation to the rest of Cleaver’s essay, as well as the rest of Soul on Ice, this call for Baldwin to “cure” himself by seeking out his African racial and psychological origins comes as something of a surprise. Just a few paragraphs before his angry dismissal of Baldwin’s life and work, Cleaver explicitly rejected the argument that a cultural nationalism could undo the neuroses that plagued black men and women. Calls from “Black Muslims, and back to Africa advocates” for strict segregation in the name of a renewed sense of racial identity were merely the inversion of this racial death-wish—an attempt to deny the potential social value of integration.20 For Cleaver, the “cure” for black Americans’ racial death-wish lay not in separatism but in a more thoroughgoing miscegenation. Society would only overcome the innumerable effects of its protracted racial power struggle through a process of physical, mental, racial, and sexual “convalescence,” in which the “black,” “white,” “male,” and “female” moments of human existence and experience would be “grafted onto” one another. Before one could hope to enter into this process, however, one would need to understand more fully the intricate and intimate relations of sexual and racial power that structured American history.

Every social order, Cleaver wrote, reproduced itself through the projection of a corresponding “sexual image,” an ideal to which all individuals and sexual relations in a given society aspired.21 A utopian society, he claimed, taking a page from Plato’s Symposium, would approximate the “Unitary Sexual Image,” a glimpse of a prelapsarian past in which the male and female “halves” of the human race were fused into one being, “a unity in which the male and female realize[d] their true nature.”22 When, in the course of history, the “Primeval Sphere” represented in this Unitary Sexual Image divided itself (an event described only as an “evolutionary choice made long ago in some misty past”) the male and female hemispheres of the human being were separated from one another.23 From that moment, these hemispheres felt an “eternal and unwavering motivation . . . to transcend the Primeval Mitosis and achieve supreme identity in the Apocalyptic Fusion.”24 Until the late 1950s, Cleaver argued, this fusion had been impossible largely because historical impediments had thwarted all attempts to achieve it. Primary among those impediments had been class antagonism.

Class-based societies were sustained by the individual’s alienation or fragmentation—two terms Cleaver used virtually interchangeably. These societies were able to reproduce themselves only through the projection of multiple images of “fragmented sexuality.” Rather than viewing themselves in terms of their alienation from the Unitary Sexual Image, individuals in class-based societies evaluated themselves in terms of their difference from members of other social classes. The upper and lower classes thus both saw themselves as somehow deficient, but, according to Cleaver, their deficiencies were conceived, incorrectly, through comparisons to flawed models. Just when it appears that Cleaver would like to reduce all class conflict to a function of this sexual alienation, however, he argues precisely the opposite. Foregoing any attempt to measure the distance between the individual and the Unitary Sexual Image, he instead offers a description of the psychological, social, and, of course, sexual distance separating men of the elite classes from those of the lower classes. It was in this distance, the “fragmentation” of society and the individual, that the historical roots of racial antagonism lay.

This fragmentation had been cemented, he explained, through the functional separation of “Man as thinker” from “Man as doer.” As he put it, “When the self is fragmented by the operation of the laws and forces of Class Society, men in the elite classes usurp the controlling and Administrative Function of the society as a whole—i.e., they usurp the administrative component in the nature and biology of the men in the classes below them.”25 Men of the upper classes, in an attempt to insulate themselves from all reminders of bodily existence, expropriated the minds of lower-class men, forcing those men to labor in their service. Men of the lower classes were thus reduced to mere physicality, as the “administrative component in their own personalities” was “denied expression.”26 As in the Hegelian model of lordship and bondage, these men are forced to be the body that the administrators require yet renounce. In a racially homogeneous society this distinction between laborers and administrators would at least appear to be fluid: with no visible difference between the elite and the lower classes, individuals could more easily imagine occupying a social position different from their own. A field hand could dream of becoming a landowner, for example, and a landowner could perhaps even envision himself working the soil. In the United States, however, the alienation of mind from body appeared absolute, as the class antagonisms upon which this alienation rested were ultimately figured as the putatively biological and, more importantly, visible difference between black and white.

Nevertheless, in spite of the social and historical power consolidated in the figure of the Omnipotent Administrator, the title Cleaver uses to refer to (white) men of the upper classes, these men were inevitably filled with anxiety. To deny his physicality, the Omnipotent Administrator had been forced to renounce his own masculinity. This figure was “markedly effeminate and delicate by reason of his explicit abdication of his body.”27 As a result, Cleaver wrote, women of the elite classes, compelled to maintain heterosexual relationships with these Omnipotent Administrators, had been forced to affect a kind of “ultrafemininity.” To assuage the fears of the Omnipotent Administrators, they had gone to every extreme to deny their own corporeality. Like the Omnipotent Administrator, therefore, the “Ultrafeminine” eschewed all manual labor, and projected the “domestic component” of her character onto the women of the lower classes. In doing so, she expropriated the femininity of these “Subfeminines,” or “Amazons” as Cleaver calls them, redoubling her own so that the Omnipotent Administrator might appear masculine by contrast.

Men of the lower classes were forced to occupy an equally precarious and contradictory position. On one hand, relegated to a purely physical existence, these men appeared somehow “Supermasculine.” As Cleaver puts it, “The men most alienated from the mind, least diluted by admixture of the Mind, will be perceived as the most masculine manifestations of the body.”28 But these “Supermasculine Menials,” as he labeled them, signified through the very bodiliness that had been used to oppress them the instability of the Omnipotent Administrator’s position. They served as a constant reminder to the men of the upper classes that any social or political power they might hold was ultimately founded in a ruse. In spite of his position, therefore, the Omnipotent Administrator secretly resented the lower classes. He was “launched on a perpetual search for his alienated body,” becoming, in the process, either “a worshiper of physical prowess” or disgusted by “the body and everything associated with it.” Left to fear his own impotence, the Omnipotent Administrator’s “profoundest need is for evidence of his virility. His opposite, the Body, the Supermasculine Menial, is a threat to his self-concept.. . . . Yet, because of the infirmity in his image and being which moves him to worship masculinity and physical prowess, the Omnipotent Administrator cannot help but covertly, and perhaps in an extremely sublimated guise, envy the bodies and strength of the most alienated men beneath him.”29 In a cruel twist, the Supermasculine Menial, forced to enact an exaggerated version of his own physicality, is mythologized. In the mind of the Omnipotent Administrator, he becomes a hypersexual being. For this he is both despised and admired. He serves as both the ground against which the Omnipotent Administrator defines himself, and the “psychic bridegroom” of the Ultrafeminine, who, Cleaver argues, receives only frustration from her relations with the Omnipotent Administrator.

The historical myth of the “Primeval Mitosis” aside, Cleaver’s theory of the relations between race, class, gender, and sexual identities was hardly unique. In 1966 sociologist Calvin C. Hernton echoed these arguments regarding the interconnectedness of white and black male sexuality when he wrote that the self-esteem of white males “is in a constant state of sexual anxiety in all matters dealing with race relations. So is the Negro’s, because his life, too, is enmeshed in the absurd system of racial hatred in America. . . . [He] cannot help but see himself as at once sexually affirmed and negated. While the Negro is portrayed as a great ‘walking phallus’ with satyrlike potency, he is denied the execution of that potency.”30 As Frantz Fanon so succinctly formulated this impasse in Black Skin, White Masks, which, it is worth noting, first appeared in English in 1967, “The Negro is fixated at the genital; or at any rate he has been fixated there.”31 According to Fanon, when confronted with the black male, the white male feels compelled “to personify The Other,” and thus convinces himself that “the Negro is a beast.”32 Yet alongside his intense fear of the black male’s physicality there is an equally strong attraction: “If it is not the length of the penis, then it is the sexual potency that impresses him. . . . The Other will become the mainstay of his preoccupations and desires.”33

What is most interesting about this fixation, at least for my own purposes, is the prominent role it played in the formulation of Black Power politics. As literary theorist Robyn Wiegman has argued, many proponents of black liberation looked merely to invert the racial and sexual relations of white and black men, and thus turned the mythical potency of the black male into one of the animating concepts of that movement. In her essay “The Anatomy of Lynching,” Wiegman demonstrates the ways in which much of the rhetoric of Black Power, from Cleaver’s call for the reassertion of a fully realized black “manhood” to LeRoi Jones’s assertion that “Most American white men are trained to be fags,” simply turned these racial and sexual stereotypes on their heads.34 “The threat that this inversion pose[d] to the cultural framework of white masculine power cannot be underestimated,” she writes, “as Black Power quite rightly read lynching and castration as disciplinary mechanisms saturated by the hierarchical logic of sexual difference.”35 Regardless of its liabilities, Wiegman argues, the “intense masculinization” attributed to the black male following the abolition of slavery as a justification for the highly ritualized and sexualized practice of lynching provided these young men with a ready-made form for the performance of social antagonism. In writing that “most American white men are trained to be fags,” then, Jones looked not to interrogate the myth of the black male as hypersexualized beast, but to draw attention to the striking homoeroticism of practices such as lynching, and, by extension, racial oppression as such, in an effort to invert the power relations of black and white males in America.

For Cleaver, though, the key to abolishing the contradictory sexual and social roles of the “Omnipotent Administrator” and the “Supermasculine Menial” was not the reclamation of any “satyrlike potency.” Rather, the solution lay in the reunification of body and mind, the fusion, within white and black men and women, of both menial and administrative faculties. And to the dismay of the Omnipotent Administrators, he explained, American society was already in the midst of its own “convalescence.” “If the separation of the black and white people in America along the color line had the effect, in terms of social imagery, of separating the Mind from the Body,” he writes, the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education was “a major surgical operation performed by nine men in black robes on the racial Maginot Line which is imbedded as deep as sex or the lust for lucre in the schismatic American psyche. This piece of social surgery, if successful . . . is more marvelous than a successful heart transplant would be, for it was meant to graft the nation’s Mind back onto its Body and vice versa.”36 In declaring the doctrine of “separate but equal” to be unconstitutional, the Supreme Court had laid the groundwork for racial equality in America. Thus, in what were potentially the final moments of an American culture headed for “chaos and disaster,” a “lascivious ghost” appeared and guided the nation “down a smooth highway that leads to the future and life.”37 And in the years since the Supreme Court’s decision, the record was “clear and unequivocal . . . the whites have had to turn to the Blacks for a clue on how to swing with the Body, while the blacks have had to turn to the whites for the secret of the Mind.”38 As blacks attended previously white schools and boycotted buses, Elvis Presley appeared on television “sowing seeds of a new rhythm and style in the white souls of the white youth of America.”39 Once these initial “bridges” were erected between the Body and Mind, Cleaver wrote, the mutual attraction of society’s figurative halves could never again be denied. As much as those who opposed this personal and collective reunification “would strike out in the dark against the manifestations of turning, showing the protocol of Southern Hospitality reserved for Niggers and Nigger Lovers—SCHWERNER—CHANEY—GOODMAN—it was still too late.” The culture of racial convalescence had already been established. “For not only had Luci Baines Johnson danced the Watusi in public with Killer Joe, but the Beatles were on the scene, injecting Negritude by the ton into the whites, in this post–Elvis Presley–beatnik era of ferment.”40

In some sense it is thus surprising to think that at the very moment that the “future and life” of America were said to lie in an individual and social fusion of Body and Mind, masculinity and femininity, Cleaver was about to embark on a political career that emblematized not a utopian androgyny or racial hybridity but the image of the black male as “the bestial excess of an overly phallic primitivity.”

Upon his release from prison in 1966, Cleaver moved to San Francisco, where he wrote frequently for Ramparts magazine and helped found a cultural center known as the Black House. According to historian Kathleen Rout, “Cleaver’s dream in 1966 had been to cut off all contact with the criminal world and to work to benefit himself, his race, and his country.”41 Much as he began with hopes of participating in a cultural revolution, however, early in 1967 Cleaver’s political career appeared to undergo a dramatic transformation. In February of that year, a San Francisco–based organization known as the Black Panther Party of Northern California had planned a memorial rally in honor of slain civil rights leader Malcolm X, at which Betty Shabazz, Malcolm’s widow, was to be the guest of honor.42 As this organization, with whom Cleaver was loosely affiliated through his work at the Black House, was concerned primarily with issues of cultural nationalism rather than armed revolution, members were reticent to carry loaded weapons for fear of running afoul of the law. They were therefore in search of bodyguards capable of escorting Ms. Shabazz safely to and from the event. For this they had contacted another, unrelated group from Oakland calling itself the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, which had recently attracted a great deal of attention with a practice known as “Panther Patrols.”

In these patrols, carloads of armed party members would follow and “observe” the actions of officers from the Oakland Police Department. When the officers either made a traffic stop or simply questioned someone on foot who looked “suspicious,” the Panthers, each carrying either a pistol or a shotgun, would climb out of their own car and observe the interaction from a “safe” distance. The patrols were entirely legal—laws concerning the possession of firearms and interference with police procedures were studied scrupulously in their planning—but for the officers they were wholly unnerving. In Oakland, a city in which accusations of police brutality were common, a group of armed black men (and eventually women) roaming the streets citing laws and legal codes regarding arrest procedures and encouraging members of the community to join them, engendered a profound reversal of long-standing power relations. And although these patrols gave rise, in turn, to a focused campaign of harassment by the Oakland Police Department, they nonetheless earned the Panthers a local reputation as something like the vanguard in the struggle for black liberation. It should thus come as no surprise that the San Francisco Panthers would have asked Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the Oakland Panthers’ founders, to provide protection for Ms. Shabazz. Nor is it surprising that Newton and Seale, who saw themselves and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as Malcolm X’s true legatees, leapt at the offer. To them, it seemed the perfect opportunity to generate greater publicity for their party, and to show the people of the Bay Area just which Black Panther Party was truly serious in its revolutionary aspirations.

On the day of the rally, Newton and a cadre of Oakland Panthers arrived, fully armed, to meet Shabazz at the airport. The police, watching anxiously, were effectively helpless to stop the Panthers, for as always their carrying of firearms conformed precisely to the letter of the law. The party members made their way through the airport fully armed, and escorted Shabazz to the San Francisco offices of Ramparts magazine, where she sat for an interview with Cleaver. When she emerged from the building surrounded by Newton and the Panthers, a local television cameraman stepped closer for a clearer view. As Shabazz had asked not to be photographed, Newton placed a magazine in front of the camera’s lens. When the cameraman grabbed the magazine and tried to push Newton out of the way, Newton sensed a golden opportunity. He dropped the magazine, punched the cameraman, and demanded that his adversary be arrested for assault. The police, of course, refused, telling Newton that he, if anyone, should be arrested for assault. The Panthers responded by surrounding the police with their shotguns and rifles drawn. The few officers that were there, each carrying only a revolver, were outnumbered and overpowered. In broad daylight, on camera, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense had once again rendered the police visibly vulnerable.

In contrast to Wiegman’s contention, rather than simply inverting the standard lynching narrative, a standoff like this one, not to mention those that often resulted from the Panther Patrols, seemed to invoke the black folk character known as the “badman,” an outlaw hero who, as John W. Roberts explains, defied legal authorities and thus came to be seen as something like a champion of the people. Having begun, in the wake of emancipation, to see the forms of structural racism as the greatest obstacle to their freedom and equality, the black community embraced the figure of the badman. From Stackolee to John Hardy, the badman, associated “with a kind of secular anarchy peculiar to the experience of free black people,” breaks the law not for purely selfish reasons but to “restore a natural balance . . . in the social world.”43 Often starting as a participant “in a lifestyle in which illegal activities are pervasive,” the badman inevitably undergoes a personal, political transformation.44 With an act of spectacular violence, he embarks on a journey in which his deeds begin to serve ends beyond mere self-preservation; they begin, as Roberts puts it, to serve “as an emulative model of heroic action.”45 African American readers saw these deeds, which, to others, might appear simply illegal, as being based in a higher morality. They interpreted the badman’s violent confrontations with authority as “a reflection of values guiding action traditionally accepted as advantageous in maintaining the harmony and integrity of black communal life.”46 For this reason, according to Roberts, the badman was the opposite of the “bad nigger,” whose violent behavior was never directed at any goal beyond immediate, personal gratification, and so inspired fear in blacks as much as whites.47 Unlike the badman, who helped to define and demarcate the black community in opposition to the “law,” the “bad nigger” provided police with an excuse to enter and intervene in that community, thereby threatening its solidarity. As Jon Michael Spencer has written more recently, whereas the badman practices “self-determinative politico-moral leadership,” the “bad nigger” is caught in a cycle of “narcissism and hedonism”; simply put, his acts are “genocidal.”48 Where Civil Rights leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr., looked to avoid both of these characterizations, attempting instead to speak to white America in its own terms, Newton and the Panthers seemed to feel that the black folk tradition could in fact be a useful tool in organizing within the black community.

Appropriately, in recounting the standoff between the Panthers and the police, Cleaver wrote, almost literally, as if he were retelling a folk tale. When Ramparts staff members asked Cleaver who that was challenging an officer to draw his gun, he told them only that it was “the baddest motherfucker I’ve ever seen. I was thinking, staring at Huey surrounded by all those cops and daring one of them to draw, ‘Goddamn that nigger is c-r-a-z-y!’ Then the cop facing Huey gave it up. He heaved a heavy sigh and lowered his head. Huey literally laughed in his face and then went off up the street at a jaunty pace, disappearing in a blaze of dazzling sunlight.”49 Cleaver’s account was undoubtedly embellished, but all the same, or perhaps for that very reason, it points to something quite important. Although surprising to the officers, the particular way in which Newton and the Panthers presented themselves as real-life badmen was all too conventional. Cleaver’s retelling allows one to see that, drawing on more than just the black folk tradition, Newton’s “revolutionary” tactics also drew heavily on the standard forms of mass culture. The “vanguard” of the struggle for black liberation, in other words, had begun to look very much like they had been lifted straight from a Saturday matinee. As virtually any fan of midcentury cinema can attest, armed outlaws fighting for “the people,” standing up to lawmen acting on behalf of a cruel, oppressive system were all too common in films of the period. Thus, one reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle quipped, “If a Hollywood director were to choose [the Panthers] as stars of a movie melodrama of revolution, he would be accused of typecasting.”50 The Panthers, for all of their apparent revolutionary zeal, seemed almost too perfect for the role of urban American guerrilla warriors. Their popularity with local media therefore seemed both shocking and, at the same time, entirely predictable.51

Rather than dismissing the Panthers’ revolutionary tactics as being inherently compromised for this reason, Cleaver joined the party shortly after the scene in front of Ramparts, taking a position as the party’s Minister of Information. Accepting nearly full responsibility for the party’s public relations, Cleaver began working with Newton and Seale to design actions that would capture the imagination not only of the people but of reporters and photographers as well.

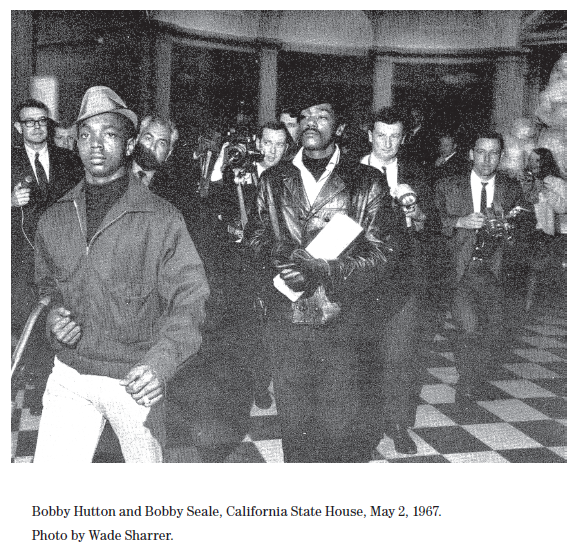

A rare opportunity soon presented itself when Newton and Seale spoke as guests on a local radio talk show in Oakland. During the show, conservative assemblyman Donald Mulford phoned the station to announce that he planned to introduce a bill that would “get” the Panthers by outlawing the carrying of firearms in California.52 The legislation was obviously designed to bring an end to the Panther Patrols, and, likewise, Mulford’s public announcement was an attempt to counter the growing embarrassment that authorities across the state were suffering at the hands of various local party chapters. In response, therefore, Cleaver, Newton, and Seale orchestrated what became perhaps the most famous of the Panthers’ actions: their descent upon the state capitol in Sacramento.

On May 2, thirty Panthers, twenty of whom were visibly armed, entered the capitol building in Sacramento seeking to take the floor for a public address during a meeting of the California state legislature. Once inside the building, after a series of wrong turns, the group found its way to the floor, but was quickly ushered into a separate conference room. There Seale read the Panthers’ prepared statement, “Executive Mandate Number One,” for a group of photographers and journalists. The text, prepared by Seale, Newton, and Cleaver, referenced the recent police slaying of a black teenager named Denzil Dowell in Richmond, California, and decried the Mulford bill for its attempt to remove guns from the hands of the lower classes. Although the event’s climax proved relatively sapless—the Panthers, effectively declawed, delivered their statement from a peripheral conference room while the bill passed in the legislature—the party had achieved its goal nonetheless. Cleaver, Newton, and Seale had conceived of the event as the historical counterpoint to the 1963 March on Washington. Where earlier demonstrators avoided even the suggestion of anger or violence, lest Congress and television viewers get the impression that they were attempting to force the passage of civil rights legislation, the Panthers deliberately courted that perception. Their plan was not to bully legislators into rejecting Mulford’s bill but to force reporters to pay attention. “That we would not change any laws was irrelevant, and all of us . . . realized that from the start,” Newton later explained. “Since we were resigned to a runaround in Sacramento, we decided to raise the encounter to a higher level.”53 Their goal was to use the media to deliver the party’s message to every potential ally and enemy in the state: “Dozens of reporters and photographers haunt the capitol waiting for a story. This made it the perfect forum for our proclamation.”54 In 1967 a sit-in was no longer newsworthy. To appeal to the media, activists would have to offer reporters something truly spectacular.

Nevertheless, while Newton admitted that the Panthers had carried their guns into the building to capture the reporters’ attention, he insisted that the degree to which members of the press were fascinated by this was truly bemusing. Seeing the breaking news on television that afternoon, he wrote, he could not help but be surprised. By carrying guns into a meeting of the legislature the Panthers had ensured themselves a spot on the news but had obscured their “revolutionary” message. “Executive Mandate Number One” was “definitely going out,” Newton recalled. “Bobby read it twice, but the press and the people assembled were so amazed at the Black Panthers’ presence, and particularly the weapons, that few appeared to hear the important thing.”55 To correct the mass media’s distorted coverage Newton and Seale planned a special edition of the party’s newspaper, the Black Panther, that would tell “the truth about Sacramento.” As Seale later wrote, it was important for the Panthers to provide their side of the story, for “there were so many lies about the Black Panther Party. . . . Lies by the regular mass media—television and radio and the newspapers—those who thought the Panthers were just a bunch of jive, just a bunch of crazy people with guns.”56 The Black Panther would present the party’s official account of the events that took place in Sacramento, counteracting the media’s sensationalism with the truth.

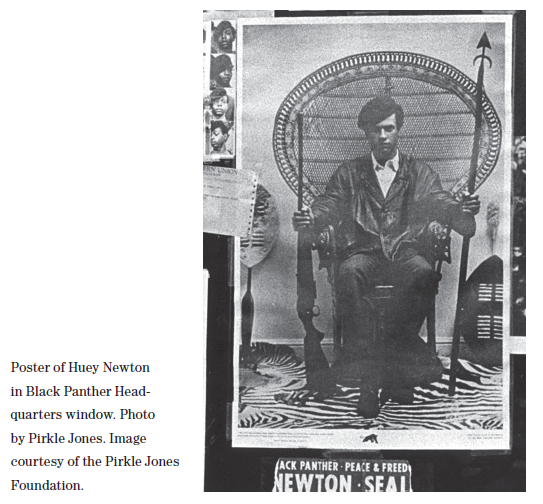

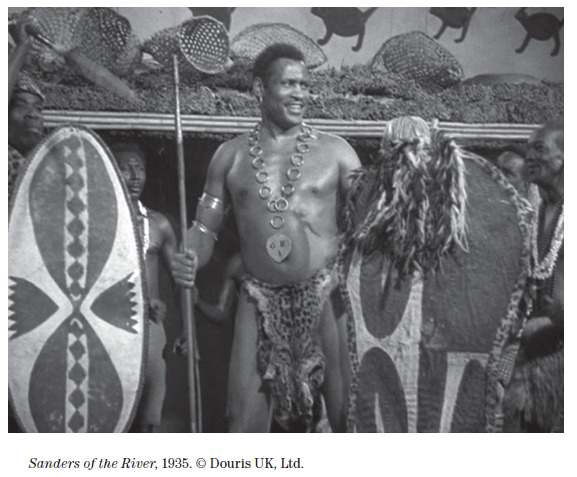

Upon Cleaver’s urging, however, the “truth” about Sacramento ran alongside what would ultimately become the most reproduced of all Panther images: a photograph of Newton seated in a wicker throne, holding a spear in one hand and a rifle in the other. Far from telling the “truth” about party activities and ideologies, the photograph further embellished the mythology of Newton and the Panthers. By presenting Newton in his full Panther uniform—white shirt, black pants, black shoes, black leather jacket, and a black beret—and surrounding him with a collection of objects connoting what one might call, taking a cue from Roland Barthes, a stereotypical “Africanicity,” the photograph drew a hackneyed parallel between the struggles for black liberation being waged almost concurrently on the two continents. Although the African liberation struggles were certainly fought with guns, this juxtaposition of rifle and spear, Black Panther wardrobe and tribal shields, Huey Newton and what looked to be a selection of props left over from Sanders of the River (the film famously disowned by star Paul Robeson because of its blatant racism) served to encode the Panthers’ political project in not only racial but also in mass cultural terms. Ironically, Newton claimed to dislike the image for this very reason. On one hand, from the time of the party’s founding, he and Seale had taken great care to emphasize the Panthers’ opposition to the rhetoric of cultural nationalism and racial separatism. On the other hand, the image appeared to place undue emphasis on Newton as an individual, thereby betraying the party’s efforts to forge a collective, community-based political movement. To present any single Panther as a celebrity, the new messiah of black liberation, risked sending conflicting messages to the Black Panther’s readers. The image, one might say, came uncomfortably close to suggesting something like a rapprochement of the vanguard and kitsch.

To Newton’s dismay, this seemed to be exactly what Cleaver wanted from the image. Cleaver, along with Beverly Axelrod (the attorney who had helped negotiate his release from prison in 1966 and at whose house the Panthers had worked on the newspaper), assembled these props, and arranged for a “white Mother Country radical” to take the photograph. Upon seeing the final prints, Cleaver insisted that the image be featured in each subsequent issue of the Black Panther, that local offices display it prominently, and that copies be made available for sale in the form of a sixteen-by-twenty poster. Few seemed to understand his attachment to the photograph. As his longtime friend, and eventual Yippie, Stew Albert recalls, a number of the party’s supporters had reservations as well. “Cleaver showed up at my pad and wanted to put up a large personality poster of Huey,” he later wrote. “Because Eldridge was so happy with his new friends, I agreed. But when he gave me a bunch of posters for my ‘associates,’ I felt unspoken reservations about their corniness. Besides, personality posters were relatively new. Even our San Francisco rock stars hadn’t as yet made use of them. They seemed narcissistic and quasi-cultic, not really ideal food for egalitarian revolutionaries.”57 Not unlike Newton, Albert was, at least at the time, uncomfortable with the photograph because it presented the Black Panther Party less as the vanguard of a “people’s revolution” than as an unwitting mirror of the society its members claimed to despise. The poster thus seemed as if it might alienate the party from all potential allies, both black and white.

For many involved in Black Power politics, it was all just too much. Radio interviews, media stunts, publicity posters: were the Panthers truly focused on revolution, or were their tactics just an attempt to gain fame and notoriety? In the summer of 1967 Newton responded to questions like this in an essay explaining “the correct handling of a revolution,” arguing that it would be a mistake for radicals to shy away from publicity, as the “sleeping masses must be bombarded with the correct approach to struggle and the party must use all means available to get this information across to the masses.” The party’s critics seemed to “want the people to say what they themselves are afraid to do. That kind of revolutionary is a coward and a hypocrite.”58 A “real” revolutionary had to be willing to risk his/her life, and to stand in the face of the “dog power structure” not to ask for equal rights but to show that s/he would take them by any means necessary. To inspire the masses to make a revolution themselves, the vanguard party would have to show them how. True revolutionaries, that is, would make themselves visible. For this reason, Newton continued, the Watts Riots, much as the violence may have caused many young blacks to fear the repercussions of openly defying authority, were nevertheless a powerful revolutionary catalyst. They did not bring about real, qualitative change—the immediate effect of the riots, after all, was the death of large numbers of young blacks—but for Newton that was not the point. The riots in Watts, Philadelphia, Chicago, Jersey City, and Detroit, to name only a few, provided an expression of the very real frustration and hostility felt by the inner-city poor. They were, as Fanon called the anticolonial uprisings in 1950s Africa “the sign of the irrevocable decay, the gangrene ever present at the heart of colonial domination.”59 At the same time, though, Newton was equally interested in the way in which these actions seemed to appeal to the media. While any riot was destined to end disastrously for its participants, those in Watts had been “transmitted across the country to all the ghettoes of the Black nation. The identity of the first man who threw a Molotov cocktail is not known by the masses, yet they respect and imitate his action.”60

For all of the very real damage they had caused, the Watts riots provided a stunning image, one as inspiring for many young blacks as it was dreadful for whites.61 For this reason, as important as it might be to organize in individual neighborhoods, if the vanguard hoped to foment revolution on a national (or international) level, local interventions would never be sufficient. They would need to distribute images of their activities to a mass audience; they would need, like the rioters in Watts, to get the country’s attention. “Millions and millions of oppressed people may not know members of the vanguard party personally, but they will learn of its activities and its proper strategy for liberation through an indirect acquaintance provided by the mass media.”62 To “capture the imagination” of the people, revolutionaries would have to engage the press.

To be sure, disagreements over whether, or how, civil rights or Black Power advocates should seek to use the media as a tool were nothing new. Questions about the media’s role in depicting and defining racial politics, an integral part of the civil rights movement, from the March on Washington to the Selma-to-Montgomery voting marches of 1965, were quite familiar by the time the Panthers arrived on the scene. Speaking of the March on Washington, for example, Malcolm X, who had himself appeared on television numerous times in the late 1950s and early 1960s, denounced the event’s organizers for having played so obviously to the cameras. The problem was not, as one might expect, that the media distorted the demonstrators’ message. In fact, he said, the media had no need to misrepresent what had happened, for the entire event had been created just for them: “The marchers had been . . . told how to arrive, when, where to arrive, where to assemble, when to start marching, the route to march . . . even where to faint. . . . Hollywood couldn’t have topped it.”63 As historian David Carter has shown, internal tensions over media coverage of civil rights/Black Power politics can be seen quite clearly in the 1966 “Meredith March Against Fear.” As he set out to complete James Meredith’s march from Memphis to Jackson, Mississippi (Meredith had been ambushed and sent to the hospital with multiple gunshot wounds) Martin Luther King, Jr., claimed to have heard words that “fell on my ears like strange music from a foreign land.”64 Angry young blacks had begun to shout that they would no longer suffer beatings at the hands of white racists; they refused to follow King in singing “We Shall Overcome,” instead switching the hymn’s lyrics to “We Shall Overrun.” And in what was—at least for the collection of journalists following the march—the most shocking inversion, when they heard the familiar call “What do you want?” marchers responded not with the standard cry of “Freedom!” but with the much more confrontational cry of “Black Power!” This very vocal disagreement had been orchestrated by one of the other organizers behind the march, Stokely Carmichael, the new leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Carmichael and other SNCC officers had requested King’s attendance because they understood that his presence would guarantee the interest of journalists and photographers. When King arrived, however, SNCC essentially used his image against him. King, in other words, was invited to march so that SNCC might dramatize the tactical and ideological shift taking place in American racial politics.

What struck people as new, or discomfiting, in the Panthers’ actions was not so much their opportunistic staging, therefore, but the forms they chose to appropriate. These concerns regarding the Panthers’ “revolutionary” images and tactics only intensified in the months that followed the Party’s appearance in Sacramento. In October of 1967 Newton was imprisoned, charged with the murder of Oakland police officer John Frey, and Seale was involved in a series of trials, including the original conspiracy trial of the Chicago 8, and the New York trial of the Panther 21, accused of murdering undercover police officer Alex Rackley. In their absence, Cleaver surprised many Panthers by assuming the role of the party’s leader and spokesman, ushering in what David Hilliard has called the “second life of the Party.”65 Prior to Newton’s arrest, Cleaver had refused even to sign his name to the pieces he wrote for the Black Panther, preferring instead to use the byline “Minister of Information, Underground.” In Newton’s absence, however, Cleaver seemed to make a concerted effort to become the public face of the party. He exploited the interest aroused by actions like the one in Sacramento, playing upon and embellishing mass-media coverage of the party’s actions. By the time Soul on Ice appeared in February 1968, Cleaver was already a national celebrity. He traveled cross-country, making appearances on television talk shows, giving speeches to large audiences on college campuses, securing endorsements for the Panthers from celebrities such as Marlon Brando, and running for president on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket with Yippie Jerry Rubin as his running mate.66

Of course, like Newton and Seale before him, Cleaver’s role as the party’s spokesman made him the target of an organized campaign of official harassment. On April 6, in the midst of riots set off by the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Cleaver and a group of Panthers were pulled over by the Oakland police, and what the officers claimed was a routine traffic stop quickly turned into a shootout.67 After fleeing the scene, only to be trapped in the basement of a nearby home and inundated with teargas, Cleaver and fellow Panther Bobby Hutton surrendered. Hutton emerged from the home disarmed, only to be shot in the back and killed by the officers, and Cleaver, having been shot in the leg while inside the house, was arrested and imprisoned. His parole was revoked immediately, forcing him to spend the next two months fighting to regain his freedom, a legal battle that ultimately enabled him to intensify the Panthers’ media campaign.68 Upon his release from prison he began to bombard the masses not with Newton’s “correct approach to struggle” but with a series of images presenting the Panthers as defiant “Negroes with guns.” Calling upon the distinction made famous by Malcolm X, he told reporters that with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., the “field nigger” takeover of the black liberation movement had been completed. Later he wrote in a statement for Ramparts magazine, “The assassin’s bullet not only killed Dr. King, it killed a period of history. It killed a hope, and it killed a dream . . . the war has begun. The violent phase of the black liberation struggle is here, and it will spread. From that shot, from that blood, America will be painted red.”69 Cleaver was not the only one to call upon this kind of rhetoric in the wake of King’s death. As SNCC chairman H. Rap Brown wrote in his 1969 political autobiography, Die Nigger Die!, although nonviolence “might have been tactically correct at one time in order to get some sympathy for the Movement,” in 1969 “the stark reality remains that the power necessary to end racism, colonialism, capitalism and imperialism will only come through long, protracted, bloody, brutal and violent wars with our oppressors.”70 The “respectable Negroes” of the 1950s and early 1960s, Cleaver and Brown suggested, had been superceded. The violence that was purportedly inherent in every black male was on the verge of boiling over.

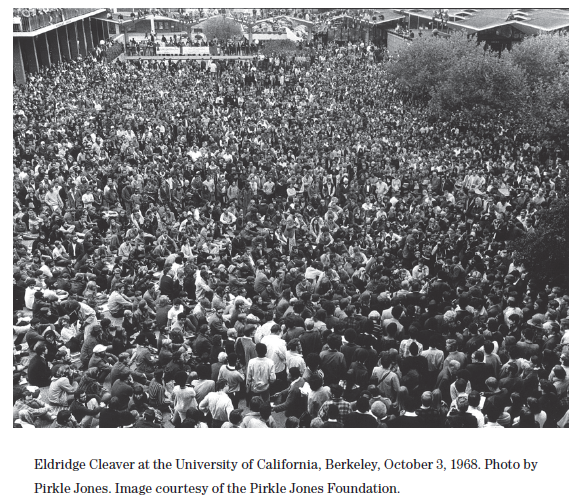

More than Brown, however, or any other Black Power spokesman for that matter, Cleaver seemed to capitalize on the perceived threat of a stereotypical black masculinity. In 1968, for example, he was invited to participate in teaching an experimental sociology course on race relations at the University of California at Berkeley. Upon hearing that Cleaver would be placed on the state’s payroll, then governor Ronald Reagan demanded that the state board of regents block the course. Asking Cleaver to speak on the causes of social unrest, Reagan said, would be like “asking Bluebeard of Paris, the wife murderer, to be a marriage counselor.”71 Reagan’s reaction, of course, only helped publicize the lecture, which, when finally held, drew such a crowd that it had to be moved out of the lecture hall and into the public square. Later that year, Robert Scheer of Ramparts magazine wrote, “As the U.C. issue splattered across California newspapers Cleaver moved . . . from Humboldt to Orange County, ‘roasting Reagan’s tail’ in a series of public addresses . . . and the TV and newspaper coverage of the duel between the Sanctimonious Reagan and the Freewheeling Cleaver was fantastic.”72 At each stop on his statewide tour, Cleaver delivered the kind of absurdly fiery rhetoric audiences had come to expect. That fall he spoke at Stanford University, opening his lecture with a pointed verbal attack on Reagan. “Fuck Ronald Reagan,” he said. “Fuck Stanford University, if that’s necessary, dig it? That may or may not be the limit of my vocabulary, I don’t know.”73 He repeated the sentence “Fuck Ronald Reagan” throughout his address, almost as if it were a kind of mantra, and at one point declared,

Someone said that [state superintendent of public instruction] Max Rafferty has a Ph.D. in physical education, in football and baseball and basketball and ball-head, I don’t know. I don’t know what his credentials are. I know that he has a yackety-yak mouth and I can only relate to one adversary at a time. I want to challenge Max Rafferty to a duel, but he’s too old to whip me, I could kick his ass. But I challenged Ronald Reagan to a duel, and I reiterate that challenge here tonight. I say that Ronald Reagan is a punk, a sissy, and a coward, and I challenge him to a duel, I challenge him. I challenge him to a duel to the death or until he says Uncle Eldridge. And I give him his choice of weapons. He can use a gun, a knife, a baseball bat or a marshmallow. And I’ll beat him to death with a marshmallow.74

While audiences seemed to hang on Cleaver’s every word, some were becoming increasingly uncomfortable with these performances. In 1970 journalist Don Schanche wrote of a conversation with a press photographer who was concerned that the Panthers, and Cleaver in particular, had not yet learned “to adjust their speech and actions to the audiences they face. . . . They want support from middle-class people, but they’re turning them off with that kind of talk.”75 For others, however, the issue was not a lack of middle-class support but the wrong kind of middle- (and upper-) class support. The caricature of Black Power that Cleaver performed seemed to resonate less with “street brothers” than with those who had no personal experience of racial discrimination. In other words, the more Reagan and Rafferty sought to silence Cleaver, the more white supporters flocked to the party. And because Cleaver’s tactics appeared almost to embrace stereotypical notions of black masculinity, the new cross-racial alliances he was cultivating seemed thoroughly problematic. As Tom Wolfe quipped, white liberals and “radicals” had been attracted to Cleaver and the Panthers not because of the party’s ideological purity but because the Panthers appealed to a kind of “nostalgie de la boue, or romanticizing of primitive souls.”76 That is to say, the white audiences that filled lecture halls and penthouse parlors to hear Cleaver speak saw the Panthers’ combination of violence and vulgarity as proof less of their revolutionary fervor than of their racial authenticity. For white audiences, whether they supported or despised the Panthers, Cleaver and other party members seemed to speak with the voice of an essential “blackness”—a violent rage that could no longer be suppressed.

Even after eventually fleeing the United States to avoid returning to prison, Cleaver, still officially a member of the party’s executive committee, continued to issue statements urging blacks to engage in armed conflict throughout America, and calling for a full-scale guerrilla war in the country, to begin on Long Island in 1969. That year, exiled in Algiers, Cleaver told journalist John McGrath that if a plan could be devised allowing him passage back into the United States, he would lead the country’s oppressed in a real uprising, one that would reveal America to be a “skeleton in armor.”77 For Newton, still in jail awaiting trial, regardless of the moral and monetary support Cleaver had secured for the party, statements like this were a serious concern. He worried that Cleaver’s rhetoric threatened not only to provoke official retaliation but also to alienate the black community. Following his release from prison in 1970, therefore, Newton began to distance the party from Cleaver’s increasingly outrageous pronouncements. References to guerrilla warfare were eschewed; the Panthers stopped patrolling; the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense became, simply, the Black Panther Party; Bobby Seale campaigned for local office; and social initiatives like the Breakfast for Children program, in which the Panthers provided poor inner-city children with free breakfast each day before school, became official talking points. Newton even renamed his position. No longer wanting to be called the “Minister of Defense,” he asked first to be known as the party’s “Supreme Commander,” and later, finding that title too self-important, settled on “Supreme Servant.”

Ignoring these obvious changes, Cleaver continued to speak of revolution. The increasing tension within the party came to a head in February 1971, when Newton was asked to appear on a local television talk show in Oakland. During the show, host Jim Dunbar phoned Cleaver in Algiers so that the three might participate in a roundtable discussion on what appeared to be the Panthers’ new direction. As the cameras rolled, rather than praising the party’s social programs as Newton had hoped, Cleaver accused Newton and the rest of the party’s leaders of cowardice.78 The Black Panther Party, he said, had lost its nerve. Not surprisingly, when the program finished, Cleaver was immediately excommunicated. Not long after, Newton wrote an essay for the Black Panther in which he claimed that Cleaver’s expulsion had been inevitable.

According to Newton, the party’s leaders had learned from their mistakes. They had begun to discourage “actions like Sacramento and police observations because we recognized that these were not the things to do in every situation or on every occasion.” The party had come to see actions such as the Panther patrols and the confrontation in front of Ramparts magazine as failures, he wrote, for “the only time an action is revolutionary is when the people relate to it in a revolutionary way.”79 Although these performances had at one time provided a model for the Black Panther Party, in the end they had proven more costly than Newton had imagined. The community had simply been unprepared to interpret the Panthers’ imagery correctly. As a result, the party had never connected with the black community in the way that he had hoped. And Cleaver, who had joined the Panthers only after seeing actions like these, emblematized this failure of understanding: “Without my knowledge, he took [the standoff in front of Ramparts] as the Revolution and the Party.”80 The initial efforts to present the Panthers as an organization of “badmen,” in other words, had backfired; viewers both black and white had mistaken the Panthers for nothing more than a group of “bad niggers.” And Cleaver, serving as the party’s de facto leader, merely perpetuated this misunderstanding. “Under the influence of Eldridge Cleaver,” Newton wrote, “the Party gave the community no alternative for dealing with us except by picking up the gun.”81 In spite of the party’s apparent growth, Cleaver’s emphasis on the image of the gun in Panther publicity had left the organization hamstrung. The people—Cleaver included—had not been ready to understand the true significance of that image. Rather than comprehending the party’s profoundly revolutionary message, many young black males felt that the Panthers’ “uniforms, the guns, the street action all added up to an image of strength,” and, like Cleaver, they came to the party seeking a “strong manhood symbol.”82 “This was a common misconception at the time—that the party was searching for badges of masculinity,” Newton wrote. But “the reverse [was] true: the Party acted as it did because we were men.”83 For Newton, those who really got it knew that manhood could never grow from the barrel of a gun.

The following year, he composed an even more damning version of this argument in an unpublished manuscript entitled “Hidden Traitor Renegade Scab: Eldridge Cleaver.” Drawing quite heavily on the essays collected in Soul on Ice, Newton argued that one could never understand Cleaver’s obsession with the image of the gun without first understanding the depth of his sexual neurosis. Cleaver, Newton argued, suffered from “paranoid dysfunctions” and “nihilistic confusion.”84 Having begun his career in the isolation of a prison cell, Cleaver had regressed upon his release to a vicious cycle of solipsism and narcissism. As a free man, Cleaver found himself unable to distinguish “between stage blood and real blood”; as a result, any discernible political ideology necessarily gave way to “wild monologues of masculine protest, and word salads of sadistic profanity directed at authority figures.”85 His confrontational style and “obsession of the gun” ultimately served to replicate the personal, psychological isolation he experienced in prison. Through violent imagery and language, Cleaver was able to avoid any and all communion, whether sexual, social, or political. His violently sexist and homophobic rants were therefore “never so political as they were rather pitiful counterphobic tactics designed to ward off . . . the political intimacy that the masses demand of their leaders.”86

As much as he claimed to have been distressed by Cleaver’s personal and political isolation, however, it was Cleaver’s “repressed homosexuality” to which Newton devoted the lion’s share of his analysis.87 According to Newton, this particular “sickness” was central to Cleaver’s persona. And, not surprisingly, the key to understanding this “sickness” lay in his famous critique of James Baldwin. In “Notes on a Native Son,” Newton explained, Cleaver may have appeared concerned with Baldwin’s political failures, but “in several places the frenzy of his denial breaks down and we catch a glimpse of a very different Eldridge Cleaver.”88 The vitriol Cleaver directed toward Baldwin, though framed as an analysis of Baldwin’s reactionary racial/sexual politics, was really a clear indication that Cleaver suffered from a form of “homophiliac phobia, or fear of the ‘female’ principle.”89 This fear had led not only to Cleaver’s repeated condemnations of same-sex desire, Newton argued, but to his personal history as a convicted rapist. Throughout his life, Cleaver had “vacillated between these mechanics of denial of homosexual panic and a pseudo-sexuality directed not at women so much as the idea of women.”90 Caught up in the convulsions and compensations of his own denial, his social, political, and literary analyses had, like his behavior, become disjointed. Baldwin had to be attacked; “masculinity” had to be equated with true liberation—Cleaver’s “sickness” allowed for nothing else.

While Baldwin had escaped “the problems of the repressed homosexual” by openly embracing his sexuality, Newton argued, Cleaver remained ensnared in his own self-hatred, a self-hatred Newton illustrated with the story of a 1967 dinner party for James Baldwin. “Cleaver had been invited,” Newton explained, and, rather surprisingly, “he in turn invited me.” More shocking still, Newton then said, “when we arrived Cleaver and Baldwin walked head onto each other and the giant 6’3” Cleaver bent down and engaged in a long, passionate french [sic] kiss with the tiny (barely 5 feet) Baldwin. I was astounded at Cleaver’s behavior because it so graphically contradicted his scathing attack on Baldwin’s homosexuality.”91 As stunning as this revelation might have seemed, for Newton it was, in retrospect, only too predictable. This was because virtually all of Cleaver’s behavior—his history as a rapist, his strident homophobia, his “obsession of the gun,” and so on—could be explained in terms of a deeply conflicted sexuality. Likewise, Cleaver’s “political” tactics, his absurd braggadocio and apparent need to constantly manufacture conflict, marked him as a man thoroughly terrified of his “‘female’ principle.” “If only this failed revolutionist had realized and accepted the fact that there is some masculinity in every female and some femininity in every male,” Newton lamented, “perhaps his energies could have been put to better use than convincing himself that he is everyone’s super stud.”92

But for Newton, the kiss between Cleaver and Baldwin, like Cleaver’s purportedly conflicted sexuality, signified more than anything else a lack of authenticity. It was the fatal slip that unraveled Cleaver’s entire persona, revealing him to be nothing more than a fraud. In Newton’s account, the inability to distinguish reality from play-acting was Cleaver’s fundamental failing as a revolutionary: he believed that stage blood was real blood, that guns and erect penises amounted to “true” masculinity, and that, in turn, the reclamation of this “true” masculinity was the equivalent of “real” liberation. According to Newton, the ability to discern truth from fiction was the key to making revolution. The Black Panther Party was, in his words, “out to create non-fiction.”93 The irony of Newton’s attempt to discredit Cleaver through what was, in effect, a form of gossipmongering/gaybaiting is therefore difficult to overlook, particularly as it came on the heels of Newton’s public profession of support for the gay liberation movement.94 But it is the ease with which Newton transformed Cleaver’s overwrought masculinity into the signifier of a profound sexual anxiety that I find so fascinating—not only because of the historical persistence of this critical operation but also because it stands in surprising contrast to the theory of racial self-presentation offered in another essay Newton penned simultaneously. As he worked on “Hidden Traitor Renegade Scab,” Newton was also composing a “Revolutionary Analysis” of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, praising the film for its clever deployment of stereotypes.

The film’s narrative revolves around the character known only as Sweetback, played by the director, Melvin Van Peebles. One night Sweetback, a young man raised in a Watts brothel, agrees to accompany two police officers to the local precinct to appear in a lineup of murder suspects. On their way to the station, the officers arrest a young black revolutionary named Moo-Moo. Before arriving at the station they stop once more, and the officers begin to beat Moo-Moo savagely. Sweetback, taking pity on the young man, comes to his defense, and in the ensuing struggle nearly kills the officers. The remainder of the film consists of an extended manhunt in which Sweetback, with the help of the “Black Community”—whom Van Peebles credits as the film’s true stars—evades the police and escapes to Mexico. On his journey, Sweetback relies on the assistance of pimps, prostitutes, preachers, and gamblers, and more than once exchanges sex for his safety—most famously, perhaps, during a scene in which he literally fucks the leader of a hostile motorcycle gang into submission. As Newton put it, “The corporate capitalist[s]” had made Sweetback available to the general public only because they had “fail[ed] to recognize the many ideas in the film.”95 Those in charge of distributing the picture saw it not as a revolutionary call to arms but as a tale of picaresque heroism revolving around the stereotype of the hypersexual black buck. By playing this role, appropriating and resignifying images that had been used to oppress black men for more than a century, Van Peebles secured national distribution for his film (not without some effort, of course), allowing his encoded “revolutionary” messages to reach millions. What made Sweetback “revolutionary,” in other words, was not, as David Joselit has argued, Van Peebles’s insistence on operating outside the studio system.96 Rather, it was his ability to make radical politics appear utterly conventional. “Van Peebles,” Newton writes, “is showing one thing on the screen but saying something more to the audience.”97 Sweetback’s sexual escapades, for example, are “always an act of survival and a step toward his liberation. That is why it is important not to view the movie as a sex film or the sexual scenes as actual sex acts. . . . The real meaning is far away from anything sexual, and so deep that you have to call it religious.”98 For Newton, when Van Peebles showed himself (and his son) having sex in the film, he did so not to titillate the audience but to re-present the stereotypes of black masculinity, to manipulate them as symbols, to “signify” as Newton puts it. Where Cleaver seemed to use stereotypical images only to propagate misunderstandings, Van Peebles had devoted his work to correcting them. By providing young black men and women with this “Revolutionary Analysis” and urging them to see the film again, Newton hoped to awaken them to the deeper, “religious” truths of its imagery.

As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., has explained, however, the political potential of the practice known as signifying (or “Signifyin(g),” as Gates writes it, noting the way the final “g” is most often silent in black vernacular speech) is not so simple. Signifyin(g) is not one operation per se but a kind of umbrella term, encapsulating the various modes of figurative language used in African American writing and speech. It is tempting to think of these practices—as Newton apparently did—as a type of direction through indirection, a way of drawing on a pre-existing language while inserting critical connotative differences. But as Gates makes clear, while Signifyin(g) may imply the speaker’s disdain for those with whom that pre-existing language is associated, the practice nevertheless underscores the hegemonic power of that language. While it suggests in some sense a “protracted argument over the nature of the sign,” it does so only by emphasizing “the chaos of ambiguity that repetition and difference . . . yield in either an aural or a visual pun.”99 Gates, therefore, describes Signifyin(g) not as a traditionally oppositional or revolutionary tactic but as a process akin to the Freudian dreamwork. The real importance of the Signifyin(g) gesture, that is, lies neither in the signifier nor in the signified (the manifest or the latent content), but in the ways in which the speaker somehow exceeds the limitations of the sign itself, exerting pressure on the signifier’s form to indicate a desire that is constitutively repressed because its articulation in existing language is impossible. What is at stake in the practice of Signifyin(g) is not revolution, therefore, but the ability to read individual African American subjectivities out of their stereotypical formulations.

Placing Gates’s theory of signification next to Newton’s “revolutionary analysis” of Sweet Sweetback raises two interrelated questions. First, if Signifyin(g) is never a pure expression of opposition, if it cannot avoid reinscribing a pre-existing language or cultural form, why was Newton so willing to offer his unqualified praise for Sweetback? And second, if re/citing a stereotypical vision of black masculinity could indeed hold revolutionary implications, what separated Van Peebles’s successful performance from Cleaver’s apparent failure? One could make quick work of the first question, of course, by suggesting that Newton simply failed to recognize that the act of Signifyin(g) would always be divided against itself. Perhaps, that is, his faith in the film’s political potential was simply naïve. Yet, while this may explain Newton’s enthusiasm regarding Sweet Sweetback’s wide release, it fails to address the far more important distinction that Newton hoped to maintain between Van Peebles and Cleaver, a distinction based, I believe, in the opposition between the “badman” and the “bad nigger.”

Once again, according to Roberts, the badman appears to break the law in a way that restores a “natural balance” to the black community. His “transgressions” are only seen as such by those charged with maintaining an official “law and order.” For those who are, in effect, the victims of that official system, the badman’s acts enable the community to define itself, to police its own borders and behaviors. And, although Van Peebles, at the end of the film, referred to Sweetback as a “baad asssss nigger,” the character very clearly draws upon the “badman” tradition. From his upbringing in a brothel to his near-murder of two police officers and his subsequent flight, the often-silent Sweetback clearly develops from one who appears merely inarticulate to one who forgoes speech in favor of action. His act of brutal violence functions as a political awakening. If anything, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song takes up the figure of the badman only to make the significance of his actions more explicit: rather than killing a dishonest criminal who violates the community’s standards of conduct, Van Peebles’s hero confronts the police directly. Where Gordon Parks’s Shaft (1971) was based in more conservative, middle-class ideals, Sweetback presented the “black community” as something like an American underclass exploited by both church and state. By taking the figure of the badman and turning him into the hero of a contemporary action film, Van Peebles hoped to reach young men and women who, though not politically active, may very well have found themselves the victims of an unjust legal system. Like the Newton of 1967, Van Peebles believed that in the late twentieth century, mass media imagery, if assembled in such a way that it “not only instructs but entertains,” was perhaps the quickest way to radicalize the “street brothers [and sisters].”100

While Van Peebles used the character of Sweetback to call upon young black men and women to enforce the borders of their community, and to combat the unjust and inappropriate intrusion of the state, Cleaver, at least in Newton’s portrait, seemed incapable of moving beyond mere publicity stunts. Much as he may have believed that his rhetoric could inspire bold, revolutionary action by the same young men and women who flocked to see Sweetback, Cleaver had failed to recognize the difference between a leading man and a revolutionary, between “stage blood and real blood.” As Newton makes clear, the Panthers eventually came to see that any attempt to bring the badman character to life would face a series of nearly insurmountable obstacles. From official harassment to popular misunderstandings, the Panthers’ early tactics had painted the party into a corner: Understood less as inspired, radical visionaries than as egotistical bullies and criminals, the Panthers failed to affect real, meaningful social change. Instead of fortifying the boundaries of the “black community,” when the badman stepped out of the folktale and into the world, he seemed only to give the state another reason to intervene. Where, in folk tales, the badman might help to define and rally the community, on the streets, face to face with the police, his actions served only to provoke the law, and thus to threaten the community’s stability. In the eyes of the authorities, in other words, the badman and the bad nigger were indistinguishable. Faced with the apparent failure of his attempts to embody the myth of the badman, therefore, Newton felt compelled to reassert the distinction between reality and fantasy, fact and fiction, revolution and theater. Fiction was the realm in which the characters of the badman and bad nigger could remain neatly separated, where the badman, as the defender of the community, could serve as an exemplary, self-conscious, moral being. In the realm of “real” political action, on the other hand, the project of building and defending a community would require a different type of action based not in intimidation and neutralization but in communication and education. For the true purpose of the “revolutionary,” in Newton’s view, was to make the people aware of their collective identity, to draw them together as a community so that they might realize a form of historical, political agency. This, in Newton’s most generous passages, is what Cleaver had never grasped. He had never, in Newton’s formulation, come to recognize the distinction between fake blood and real blood. It was not that Cleaver was unable to see the pain and suffering inflicted upon the community as a result of the Panthers’ violent images and rhetoric but that he never lost faith in the inspirational power of those performances. Cleaver the activist was ultimately incapable of separating himself from Cleaver the neurotic, whose attraction to violent imagery was rooted in deep psychic conflict.