We Can’t Work it Out

As ex-Beatles, John, Paul, George and Ringo saw their careers soar, stall and take strange turns.

by Arwen Bicknell

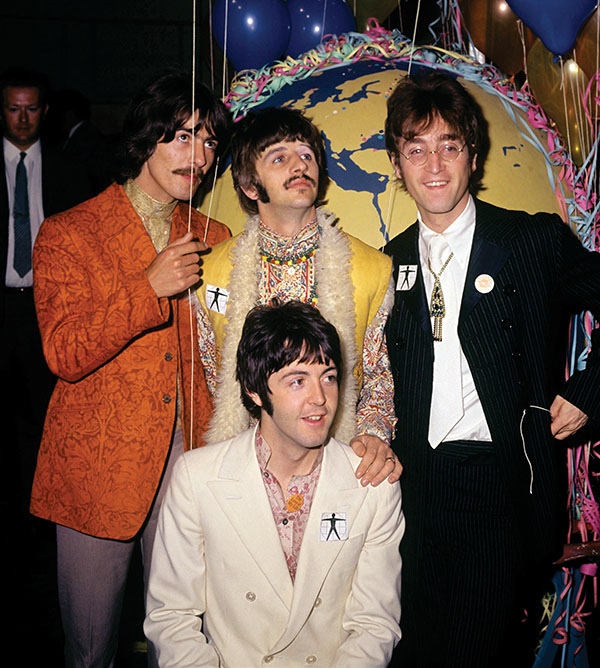

In 1967, the Beatles had enjoyed three years of widespread popularity in the U.S. It would be another three years before the band broke up, with the Fab Four pursuing solo careers.

The Beatles’ breakup didn’t happen overnight. The four Beatles grew apart personally and musically over a period of several years. The closest thing to an official announcement occurred on April 10, 1970, when Paul McCartney, promoting his first solo album, said that he did not foresee writing with John Lennon again. By then each had a distinct musical identity. Still young men — the Beatles were in their late 20s at the time of Paul’s statement — they proceeded to create solo albums at a blistering pace. By the end of 1973, the ex-Beatles had accounted for 14 studio albums since the band’s breakup. As the years passed and their output slowed, the ex-Beatles found other interests in art, politics and business. A reunion never appeared to have been seriously considered. John died in 1980; George in 2001.

John Lennon

After the breakup of the band, Lennon was the Beatle most associated with political and lifestyle activism. “Give Peace a Chance” — released before the breakup — became an anthem of the anti-war movement, and John, in his lyrics and actions, seemed intent on finding boundaries to push.

Between 1970 and 1975, Lennon released an album every year. He then spent five years on musical hiatus, focusing on his young son, Sean, and wife Yoko Ono. Lennon returned to the musical scene with Double Fatasy, an album alternating between songs performed by Lennon and by Ono. The album was falling after only three weeks on the U.K. charts, and critics disdained it as a self-indulgent portrait of marriage that might or might not have reflected their domestic reality.

But Lennon wasn’t particularly interested in critical acclaim, as he made clear in his 1980 Rolling Stone interview: “These critics, with the illusions they’ve created about artists — it’s like idol worship. They only like people when they’re on their way up … I cannot be on the way up again. … What they want is dead heroes, like Sid Vicious and James Dean. I’m not interesting in being a dead [expletive] hero. … So forget ’em, forget ’em.”

He may have had a point: When he was murdered, sales of Double Fantasy went through the roof and criticism was muted — in some cases, even withdrawn from publication.

Lennon and Ono’s 1969 wedding at the Rock of Gibralter.

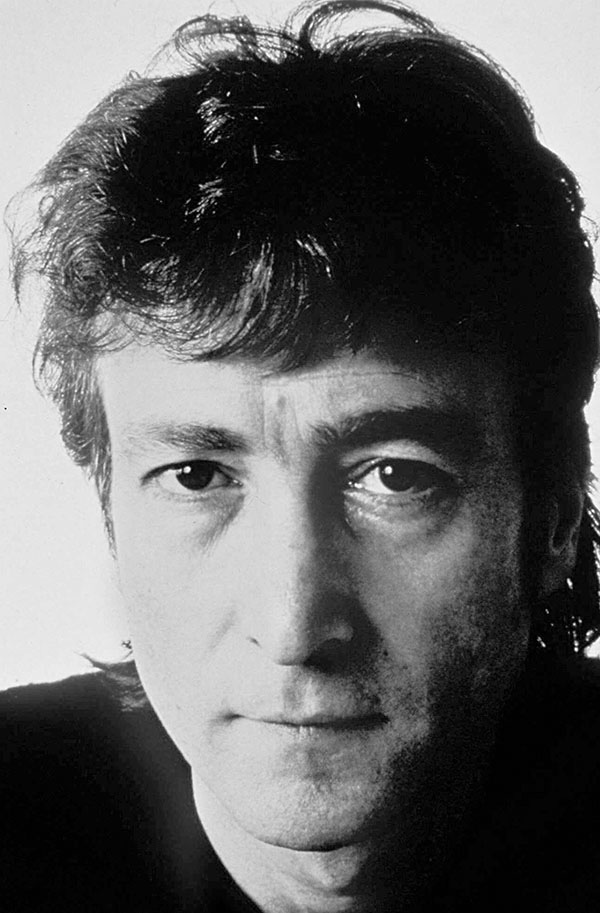

John in 1980, one month before his murder.

John’s Highlight

Few would argue that the high point of Lennon’s solo career — and his most lasting legacy — is the song “Imagine.” It’s his best-selling, best-remembered single, named by BMI as one of the 100 most-performed songs of the 20th century. Lennon himself mentioned it as one of the songs he was proudest of in a 1980 Playboy interview: “‘Imagine,’ ‘Love’ and those Plastic Ono Band songs stand up to any song that was written when I was a Beatle. Now, it may take you 20 or 30 years to appreciate that, but the fact is, if you check those songs out, you will see that it is as good as any [expletive] stuff that was ever done.” While there is something a tad hypocritical about “a millionaire who said ‘Imagine no possessions,’” as Elvis Costello pointed out in “The Other Side of Summer,” it has nonetheless become a revered anthem of world unity for three generations.

John’s Lowlight

Some Time in New York City, Lennon’s 1972 album, marked an artistic low point — Rolling Stone said, “The tunes are shallow and derivative and the words little more than sloppy nursery rhymes” — but Lennon’s ugly attacks on Paul McCartney are the most noteworthy low. McCartney was hardly blameless, attacking his ex-partner in his own lyrics, but Lennon responded with twice the vitriol. In “How Do You Sleep?” Lennon sang, “The only thing you done was yesterday,” and “The sound you make is muzak to my ears.” Ironically, this track was on Lennon’s Imagine album — proving that “a brotherhood of man” is no easy thing.

Yoko Ono told Esquire in 2011 that Lennon’s legacy is what’s really important. “His words and his music are still here. It will still affect people. And that’s the only thing they knew, anyway, when he was alive. So that’s the fate of an artist. It’s not a bad one. As long as you are what you have created,and what you wanted to share with the world, it’s still there.”

Paul McCartney

It’s impossible to sum up Paul McCartney’s post-Beatles accomplishments in anything shorter than a book. After all, he has spent more than 40 years as an ex-Beatle. Along with fronting the band Wings, many solo outings and a couple of film projects, he also dipped his toe in the classical scene and collaborated anonymously on electronic music experiments.

“I never thought that I’d particularly be doing anything,” he told NPR in 2000. “I’m not one of these people who has a vision or has a plan of what I’m doing. I’m just letting it unfold. What I’m lucky enough to be part of, and what leads me into something, I’m quite receptive to. Sometimes people would say too receptive ’cause I accept things like the Liverpool Oratorio … I was just asked … would I do anything for the Liverpool Orchestra? I said, ‘Yeah! Sure!’ without really realizing … how much work was involved.”

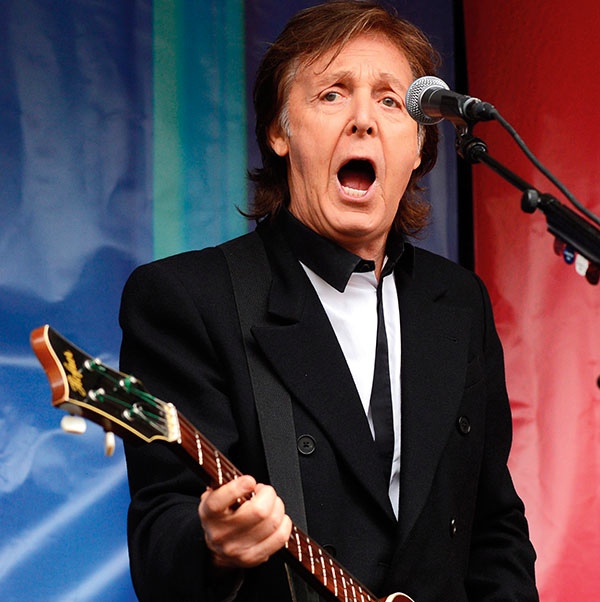

Paul in 2013.

Paul’s Highlight

It’s difficult to pick a high point for a legendary career spanning four decades. Perhaps 1979, when the Guinness Book of Records declared Paul the most successful popular music composer ever, or 1997, when he was knighted for his musical contributions. But the ultimate tribute to Paul is where he is right now. At age 71, he has released New, his 16th studio album, to acclaim. The album is a blend of reminiscence and rebirth; one song focuses on his pre-Beatles days, another on his new wife, Nancy Shevell. One of the four producers who worked on the records was Giles Martin, the son of George Martin.

Pitchfork writes, “it’s gratifying and inspiring to see the pop musician who arguably most deserves to rest on his laurels steadfastly refuse to do so. But even more remarkable than his work ethic is the fact that he’s still trying to improve himself as an artist.”

Paul’s Lowlight

Even geniuses hit sour notes, and McCartney’s came with Press to Play in 1986. Angling for a modern sound, he selected wunderkind producer Hugh Padgham, who had worked with The Police and Peter Gabriel, and he pulled in big-name guests like Eric Stewart and Pete Townshend. But work on the album dragged out for an agonizing 18 months, and everything went badly. Padgham and Stewart competed over producing duties and had even more trouble trying to tell McCartney the material was weak.

“It’s difficult to tell Paul McCartney, isn’t it?” Stewart said. “He’s a great singer, he’s written the greatest songs of all time, and you’re saying, ‘That’s not good enough.’”

Padgham’s memories were even less pleasant: “There was this conflict there. And that was something that Paul could do. He could actually wither you with a sentence if he didn’t like what you said.” When the album was finally released, the producers’ worst fears were realized, and the effort marked McCartney’s first studio collection ever to fall short of the U.S. top 20.

McCartney has suffered a lot of abuse for gravitating toward the schmaltzy (“My Love”) and the silly (“Let ’Em In”). The criticism isn’t entirely undeserved (if you’ve never seen Dana Carvey’s sendups of McCartney specifically and of vapid pop music generally as Derek Stevens, check him out on YouTube). McCartney seems to take it in stride, living well with his best revenge in “Silly Love Songs,” a No. 1 hit in the U.S.

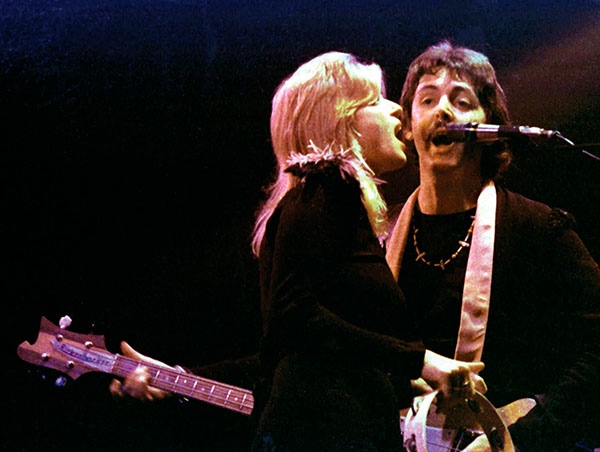

Paul and Linda McCartney harmonize during a Wings concert in 1976.

George Harrison

Before the Beatles’ breakup, Harrison had already recorded and released two solo albums and was probably the Beatle best positioned for a solo career. In 1970, he released the highly regarded album, All Things Must Pass, and the following year, he organized a charity event, the Concert for Bangladesh, that led to the release of a live triple album and, in 1972, a concert film. The event would go on to form the template for Live Aid, Farm Aid and pretty much every other musical charity event since.

Harrison continued to release new albums through the 1970s, but with waning commercial and critical success. In the early 1980s he stepped away almost entirely, taking a five-year break from recording. In 1987, he got back in the game, working with Jeff Lynne on a new album and collaborating with Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton and Elton John. The result was Cloud Nine, which included Harrison’s rendition of James Ray’s catchy, if repetitive “Got My Mind Set on You,” which would be Harrison’s biggest solo hit since “My Sweet Lord.”

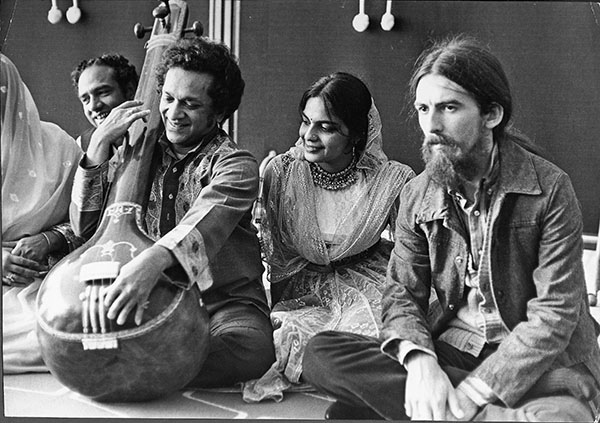

George with Ravi Shankar in 1970.

George’s Highlight

Buoyed by the success of Cloud Nine, Harrison formed the Traveling Wilburys, a band of sorts that featured Harrison, Lynne, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and Roy Orbison. “He just said he had a lot of fun with the Wilburys, and he had a lot of fun with the Beatles,” Harrison’s widow, Olivia, told Spinner.com in 2012. “I don’t think there’s anything you can compare to being in a band like the Beatles, is there? But he really had fun with Bob and Roy and Tom and Jeff. He loved being a collaborator and loved not having to do all the work himself. I think that was the main thing. And he could hang out; he liked to hang out. He didn’t always have guys and musicians to hang out with. He missed that.” The Wilburys released two albums, Volume 1 in 1988 and Volume 3 in 1990.

George’s Lowlight

“My Sweet Lord” was the biggest-selling single of 1971 in Britain. But it was also at the center of a high-profile plagiarism suit for its similarity to the 1963 Chiffons hit “He’s So Fine.” It became a sordid episode. The Beatles’ business manager, Allen Klein, entered into negotiations with Bright Tunes, the owner of the track, to resolve the issue on Harrison’s behalf by offering to buy the financially ailing publisher’s entire catalog, but no settlement could be reached before the company was forced into receivership. While that was going on, Harrison, Lennon and Starr all cut ties with Klein in 1973, which led to more lawsuits. Harrison offered to settle with Bright Tunes but was rejected; as it turned out, Klein was still trying to purchase the company and was supplying it with financial details in Harrison’s suit.

The case reached district court in 1976, and Harrison was found to have “subconsciously” plagiarized the earlier tune, but the legal machinations and repercussions would continue for years afterward. Litigation between Klein and Harrison lasted into the 1990s.

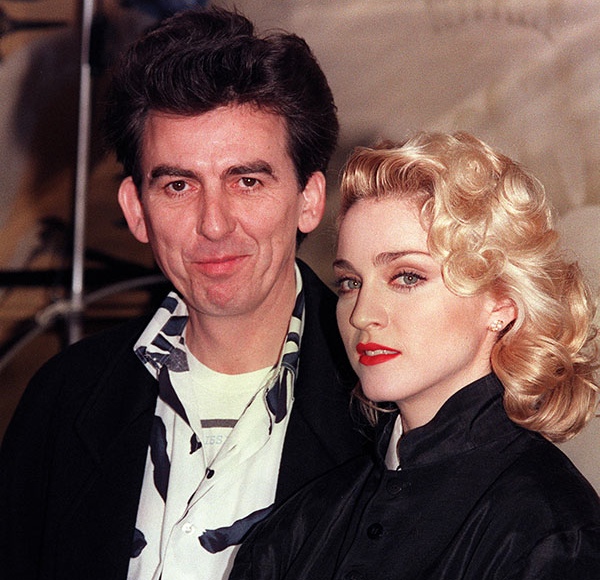

Humor fans owe a debt of gratitude to Harrison for mortgaging his home to finance production of Monty Python’s Life of Brian. Harrison founded the movie company HandMade Films to finance the film and went on to serve as executive producer for 23 more films with HandMade. Here he poses with Madonna, the star of HandMade’s Shanghai Surprise, released in 1986.

Ringo Starr

The least musically successful of the Beatles post-breakup, Starr has hardly been idle and can claim notable accomplishments in painting — he recently had an exhibit of works he made with the software MS Paint — film and music.

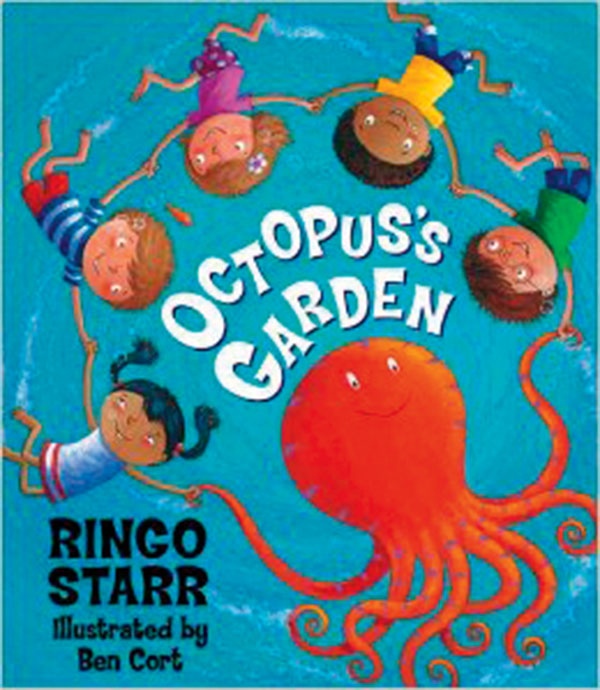

Despite being the oldest Beatle, he also has the most childlike reputation, so it’s fitting that he was the original narrator for the preschooler show Thomas the Tank Engine, released an Octopus Garden children’s book, and served as an honorary Santa Tracker and voice-over personality in 2003 and 2004 during the annual NORAD Tracks Santa program.

Starr is still recording and touring with various iterations of an All Starr Band, as he has done since 1989. “I am making records,” he told CNN in 2012. “I am going on tour, and then I am off to do whatever else I want to do. So I have a very good life.”

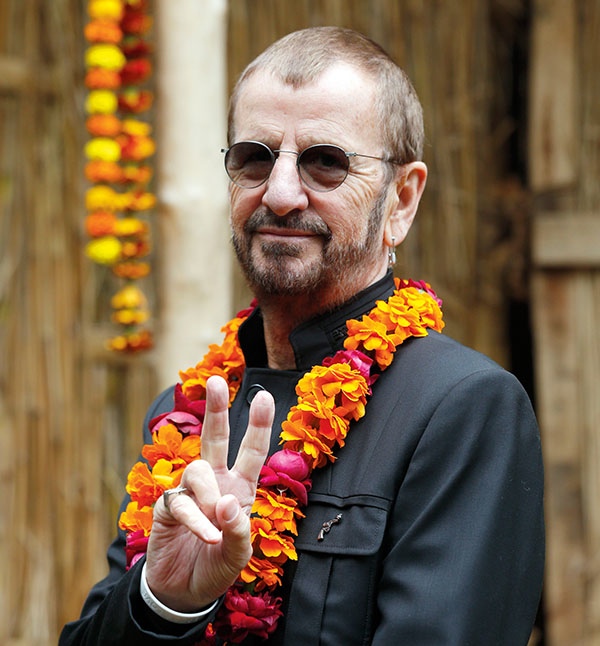

Ringo became a children’s book author in 2013.

Ringo’s Highlight

Musically, Starr peaked early. His most successful singles were “Photograph” from 1973 and “You’re Sixteen” from 1974, both of which reached No. 1 in the United States. In 1972, he released his most successful U.K. single, “Back Off Boogaloo,” which peaked at No. 2.

Ringo’s Lowlight

As with his former bandmates, the early 1980s were unkind to Starr, starting with his 1981 album Stop and Smell the Roses. An interview with Merv Griffin hints at the chaos of the recording sessions: “It’s interesting for me, when you don’t have a band, you work with a lot of different musicians, and you work with guys who have bands. I just get on the kit to give the drummer a drink. I’ve been in three bands on this album and never seen the drummer.” The album tanked, leading RCA to drop his contract. No major U.S. or U.K. label showed any interest in picking up his 1983 follow-up, Old Wave. RCA Canada finally released that album, which did poorly in all markets. It would be almost a decade before Starr would go back into the studio.

In 1981, Starr played the lead role in the hilariously bad movie Caveman. “What we needed was a charming, romantic star who was short and unprepossessing,” writer-director Carl Gottleib told an interviewer in 1981. “After Robin Williams, Dustin Hoffman and Dudley Moore, who is there? The casting chief Lynn Stallmaster suggested Ringo Starr, and I said, ‘Right!’” The movie is so awful that it essentially ended Starr’s career in movies, but it also is notable for another reasons: Starr met and married Bond girl Barbara Bach during production.