Twist & Shout

The Beatles’ U.S. tours went from triumphant to frustrating — and then were done.

by Gillian G. Gaar

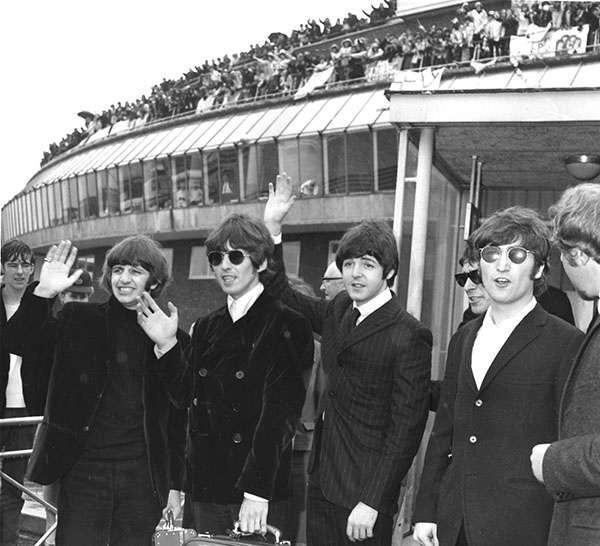

The Beatles took America by storm with multi-city tours in the summers of 1964, 1965 and 1966. At far left, the band arrives at Kennedy International Airport in New York to play at Shea Stadium.

Sixty-six shows. That’s how many opportunities fans had to see the Beatles live in North America. Those 66 shows (which included nine shows in Canada) were played in just 33 cities over the course of three summers — 1964 to 1966. Anyone who can lay claim to having seen a Beatles show in North America is very lucky indeed.

By the time the Beatles reached these shores, their live show was tailored for maximum impact. The days of sweating through six-hour sets in the clubs of Hamburg were long gone. The shows during the Beatles’ North American tours lasted barely 30 minutes — even less if they played faster. Their amps (a then-hefty 100 watts) were hopelessly inadequate to overcome the screams that erupted while the group was playing. And though the band’s music progressed fantastically in the studio during those three years, that wasn’t the case with their live shows. Claiming that their songs had become too complex to perform live, the Beatles didn’t feature a single track from their most recent album, Revolver, during their 1966 tour.

Nights to Remember

For all their inadequacies, the shows were nonetheless monumental occasions in the lives of those fortunate enough to see them. “You were there, in the same room, hearing them in person, in all their greatness,” recalls fan Judie Sims, who saw the group in both 1964 and 1966. “It was awesome!” And for the Beatles, the tours provided a welcome infusion of energy, at least initially. “When the Beatles played in America for the first time, they were already old hands,” John Lennon recalled in 1980. “It was pure craftsmanship. Only the excitement of the American kids, the American scene, made it come alive.”

Part of the excitement came from the huge crowds the band played to. In England and Europe, the Beatles played theaters and concert halls. On their North American tours, they played stadiums and ballparks, most with a capacity of 10,000-plus. They were the first band that showed a rock act could consistently draw a stadium-sized crowd. And their success opened the doors for the future stadium acts that followed: the Rolling Stones, The Who and Led Zeppelin. Beyond the Beatles’ music, their tours helped change the music industry forever.

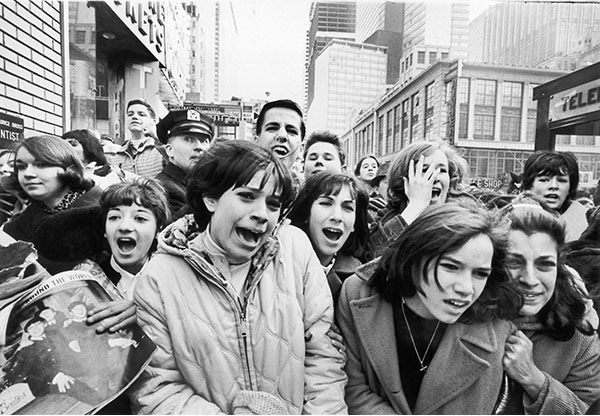

The trade-off was that it was impossible to maintain the kind of intimacy the Beatles had previously enjoyed with their audiences when they played clubs. Over time, the shows became less about the music and more about being there, less of a musical experience and more of a ritual (“bloody tribal rites,” in Lennon’s words). The fans came, screamed and waved in the frantic hope that their favorite Beatle would somehow see them from the stage. “George looked right at me,” Sims says about her first Beatles concert in Philadelphia in 1964. “I will never forget that. My cousin and I cried after it was over.”

A Fan’s Eye View

Pat Mancuso was 15 years old when she first saw a film clip of the Beatles on The Jack Paar Show in December 1963, dismissing them as “funny looking.” She changed her mind the following month while attending the last taping of American Bandstand in Philadelphia prior to the show moving to Los Angeles. Dick Clark spun “She Loves You” and “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” Mancuso recalls that, “Something clicked inside me. I think it was the excitement. They were different.”

Seven months later, Mancuso was in the audience when the Beatles played Atlantic City. “I sat in row 125 or something,” she says. “The only time I saw them was if I jumped up and down on my chair at the right time. I remember thinking ‘Who cares if I can see them? I’m breathing the same air.’ I screamed so much that I didn’t have a voice the next morning.”

The following year, Mancuso became president of the Official George Harrison Fan Club. She and her friends proudly sported homemade “I Love George” buttons when they attended the Shea Stadium show.

“The Shea 1965 concert was amazing,” she says. “I had never been in a baseball stadium before, so I was in awe over the size of it. The fans were fainting like flies and cops were carrying them away. One girl escaped the stands and ran toward the Beatles and then the cops ran after her; when they caught her, everybody booed. My father took pictures of me and my friends freaking out. I remember crying hysterically when the show was over.”

Mancuso also attended the ’66 Shea performance, sternly telling her friends they could only scream between the songs. “I don’t think anybody listened — including me!” At the show in Philadelphia, she and her friend wore blue business suits with an embroidered Harrison fan club “GHFC” emblem on the sleeves; “It didn’t really get us backstage, but I met [Beatles road manager] Mal Evans!”

Mancuso later met Harrison in England and wrote the book Do You Want to Know a Secret? The Story of the Official George Harrison Fan Club. And she has vivid memories of what made the live experience different from watching archive footage: “The excitement. The sweat. The smell of popcorn. All the teenage drama — hysterical, fainting people! All you know is that ‘Oh my God, the Beatles are right there!’ And you want your favorite Beatle to look at you.”

1964: Beatlemania, American Style

The Beatles eventually tired of what George Harrison liked to call “the mania” surrounding the group’s tours. But when they arrived for their first North American tour in August 1964, they were still enthusiastic, riding the giddy heights of the first flush of Beatlemania, American style. They had the No. 1 album in the country with A Hard Day’s Night, while the album’s title track had just left the top spot in the singles chart. Ahead of them lay their most extensive North American tour. From August 19 to September 20, they played a total of 32 shows.

The Beatles were the hottest showbiz act in the world, and everybody wanted a piece of the action. San Francisco hoped to throw a ticker-tape parade for the band to mark the tour’s beginning, but Harrison was quick to demur, not wanting to make himself a target in a country whose president had been gunned down by a sniper’s rifle less than a year earlier. It wasn’t an unfounded fear; during the tour, bomb threats were made in Las Vegas and Dallas. Ringo received a death threat when the group played Montreal (a police officer was enlisted to sit by his side during the shows to protect him).

Footage of the tour shows that when the Beatles weren’t on stage, they were constantly under siege, from fans trying to touch them (“I’d like to get a piece of the Beatles, at least!” an outraged male fan howled to one reporter), dignitaries vying for access to them, and reporters trying to squeeze in one more question (“Leonard Bern-stein likes your music. How do you like him?” Paul: “Very good. He’s, you know, great”). Being constantly pushed, as a character in A Hard Day’s Night memorably put it, between “a train and a room, a car and a room, and a room and a room.”

“It was just one long hustle,” Starr recalled to biographer Hunter Davies. “You could see [people] thinking … what’s the matter with you, you’ve only worked half an hour today. But we’d probably traveled 2,000 miles since the last half and not eaten or slept properly for two weeks.”

And that half hour contained the same 12 songs night after night, the band buzzing through them at high speed, hyped up on adrenaline. Ironically, what was arguably the tour’s most important moment would turn out to a non-musical one. On Aug. 28, after playing the first of two shows at Forest Hills Tennis Stadium in New York, the Beatles invited Bob Dylan to visit them at the Delmonico Hotel. When Dylan arrived, he produced marijuana and suggested they all light up.

Though it’s been said Dylan thus “introduced” the Beatles to pot, Harrison later admitted they had actually smoked it before in Liverpool. But this time was different. It was the moment pot became their recreational drug of choice, an influence that would soon make itself felt in the band’s music. The evening was also a rare opportunity for the Beatles to meet someone who was a genuine musical peer (they’d also met Fats Domino when they played New Orleans) and marked the beginning of their longstanding friendship with Dylan.

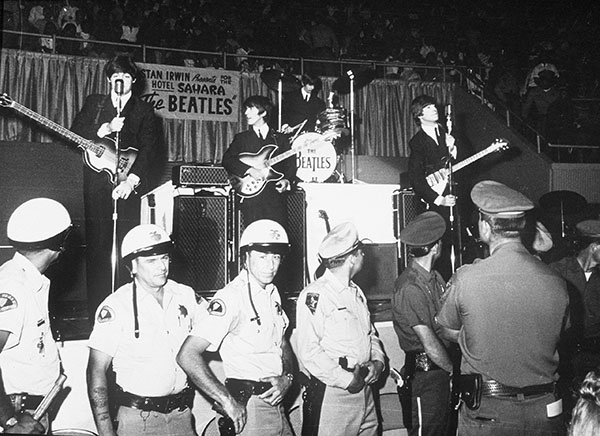

In 1964, the Beatles performed in huge venues in front of massive crowds like the Memorial Coliseum in Dallas.

The Las Vegas Convention Center

The Coliseum in Washington, D.C.

1964 Setlist

•Twist and Shout

•You Can’t Do That

•All My Loving

•She Loves You

•Things We Said Today

•Roll Over Beethoven

•Can’t Buy Me Love

•If I Fell

•I Want to Hold Your Hand

•Boys

•A Hard Day’s Night

•Long Tall Sally

Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles — Aug. 29

1965: The High Water Mark

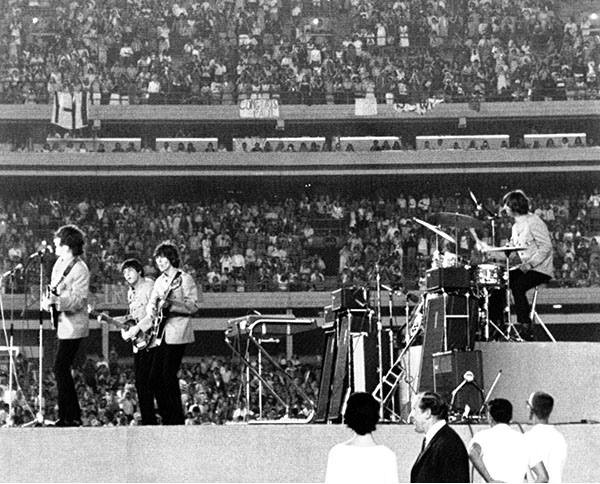

The Beatles’ 1965 North American tour was their shortest on the continent, just 15 shows in 20 days. And it began with one of the most memorable dates in their career: an Aug. 15 concert at Shea Stadium in Queens before a record audience of 55,600. The show’s promoter, Sid Bernstein (who had booked the Beatles’ Carnegie Hall concerts in February 1964), boasted that he didn’t even have a written contract for the momentous gig.

“There were no lawyers involved,” he said. “It was just Brian [Epstein] and I on the phone making the deal. You know what I would get for a contract, if I’d ever had a copy of it? Probably $100,000 at Sotheby’s.”

Twelve cameras were on hand to capture the show for the TV documentary The Beatles at Shea Stadium. It remains the best film record of the Beatles’ live act, despite the fact that the band rerecorded most of the soundtrack later in the studio. The 55,000 fans in attendance formed the largest audience a rock band had ever drawn up to that point. The Beatles’ sense of wonder as they first took the stage was clear as they looked around wide-eyed while hundreds of flashbulbs popped futilely in the distance (the stage was set up at second base, with the audience kept safely in the stands). By the set’s end, the Beatles were dripping with sweat, stomping through the closing number, “I’m Down,” before leaping into the getaway car parked at the side of the stage and driving off into the night.

The 1965 Shea Stadium concert was undeniably the high water mark of their touring years. “Fantastic, the most exciting [show] we’ve done,” as John later recalled, adding, “they could almost hear us as well.”

But their set lists were stuck in a rut; only three of the 12 songs they played each night were from 1965, and there was a surprisingly high number of cover songs in the set (three). The Beatles did not make any effort to perform anything that wasn’t a rock ’n’ roller. Their stage act was still for teenyboppers even though their music was leaving that era behind.

Two key events happened when the tour touched down in Los Angeles. While tripping on LSD around the pool on a rare day off, Lennon was sufficiently unnerved by actor Peter Fonda’s stoned ramblings that “I know what it’s like to be dead” that Lennon filed away the remark for use in a future song (“She Said, She Said”). And on the night of Aug. 27, they were ushered into the presence of the man who had so influenced them, Elvis Presley. The Beatles were so nervous they smoked pot beforehand, then loosened up enough to ask Presley, in a nice bit of foreshadowing, why he had stopped giving concerts. (Presley replied that he was too tied up with his film career.)

At the time, the Beatles couldn’t imagine being a viable act without performing live. “We couldn’t stand not doing personal appearances; we’d get bored,” Lennon said. Yet they found that touring also hampered their studio work. After the 1964 North American tour, the Beatles went straight into a U.K. tour. With little spare time left in which to craft an album of original material, they fell back on cover songs when they recorded their next album, Beatles For Sale (the songs were spread over the albums Beatles ’65 and Beatles VI in the U.S.). The shorter tours in 1965 allowed the band to more fully engage in writing and recording new music, and Rubber Soul was the happy result, followed by “Paperback Writer” and the masterful album Revolver.

More than 55,000 people saw the Beatles perform 12 songs at Shea Stadium in 1965.

1965 Setlist

•Twist and Shout

•She’s a Woman

•I Feel Fine

•Dizzy Miss Lizzy

•Ticket to Ride

•Everybody’s Trying to Be My Baby

• Can’t Buy Me Love

•Baby’s in Black

•Act Naturally

•A Hard Day’s Night

•Help

•I’m Down

Shea stadium, New York City — Aug. 15

1966: The Grind

By 1966 there was little incentive to do an extensive tour; between Aug. 12 and 29, the Beatles performed 19 shows. And they arrived embroiled in controversy, due to Lennon’s remarks to a British journalist about Christianity earlier in the year (“It will vanish and shrink … We’re more popular than Jesus now”). He apologized at the tour’s first press conference, but questions about his comments dogged the rest of the tour, and death threats were made as well. When a firecracker exploded during the group’s second show in Memphis, each Beatle instantly looked at the others, fearful that one of them had been shot.

The tensions cast a pall over the tour, and it was noted that ticket sales were also down. A return engagement at Shea Stadium failed to sell out; promoter Bernstein told The New York Times that it was a disappointment, “but I think I knew it was coming.” Grinding through the same 12 songs that no one could hear had become tiresome. “We got worse as musicians, playing the same old junk every day,” Harrison told Hunter Davies. “There was no satisfaction at all.” Bootleg recordings of the Beatles’ shows that year confirm that their playing was lackluster.

Even McCartney, the Beatle most devoted to touring, said, “Now even America was beginning to pall because of the conditions of touring and because we’d done it so many times.” So the band decided that their last ever show would be at the tour’s end, Aug. 29 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. After McCartney wailed through “Long Tall Sally,” the band put down their instruments. The Beatles’ touring days were over. Harrison later recalled thinking, “This is going to be such a relief — not to have to go through that madness anymore.”

The summer of 1966 was the last time the Beatles toured in America. They wave to fans as they leave London for the U.S.

They arrive at San Francisco to perform at Candlestick Park on Aug. 29, their final U.S. concert.

1966 Setlist

•Rock & Roll Music

•She’s a Woman

•If I Needed Someone

•Day Tripper

•Baby’s in Black

•I Feel Fine

•Yesterday

•I Wanna Be Your Man

•Nowhere Man

•Paperback Writer

•Long Tall Sally

Candlestick Park, San Francisco — Aug. 29

Just Another Memory

The Beatles’ touring years live on in official releases like The Beatles Anthology DVDs. Still, for an act of the Beatles’ stature, it’s odd that they have yet to release an album or DVD of a complete show (several performances circulate as bootleg recordings). But the Beatles never looked back on their touring days with much fondness; when they spoke of their best years as live performers, they always looked back to their pre-fame period. “We always missed the club dates ’cause that’s when we were playing music,” Lennon told Rolling Stone, “but as soon as we made it, the edges were knocked off … the Beatles’ music died then, as musicians.”

Still, those who saw the band can’t forget the sheer joy they experienced. And touring was a large part of what took the Beatles from regional fame in Britain to international stardom. Their explosive success also singlehandedly saved rock music, which had been on the wane in the U.S. in favor of surf music or dance fads like The Twist. After the Beatles, rock was never again regarded as a flash-in-the-pan novelty. During their turn on the world’s stages, they transformed rock from a teen craze to big business. Beatles concerts weren’t just shows, they were bona fide events. And as a song on a future album would put it, a splendid time was guaranteed for all.

The Lost Live Album

If Capitol Records had had their way, the Beatles’ Aug. 23, 1964 show at Hollywood Bowl would have been their first live album. A mobile three-track unit recorded the entire 12-song set. In a year which saw Capitol release five Beatles albums, a live album would have put a final touch on a year of unprecedented success.

Acetates of the show were made for the Beatles to listen to, but the group, and producer George Martin, felt the sound was abysmal compared to what they could achieve in the studio. A brief excerpt of “Twist and Shout” ended up being included on the 1964 documentary album The Beatles’ Story, which mainly consisted of interviews and clips from press conferences.

Capitol tried again the following year, recording the two shows the Beatles played at the Hollywood Bowl on Aug. 29 and 30, 1965. But the band was no more amenable to the idea of releasing a live album than it had been before, though the Aug. 30 performance of “Twist and Shout” was used in The Beatles at Shea Stadium television special. Capitol also pushed the idea of a live album in both 1966 and in 1971, but still met with refusals.

When the Beatles’ contract with the label expired in 1976, Capitol was free to release the band’s music however it wanted and plans for a live album finally went ahead. George Martin was brought in to produce, and a composite performance of 13 songs, drawn from all three shows, was released in May 1977 as The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. The album reached the No. 2 spot on the charts in the U.S. and remains the only official live album released by the group — though it has yet to appear on CD.

Gillian G. Gaar is the author of 100 Things Beatles Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Her favorite Beatles’ song? It’s a tie between “She Loves You” and “Eleanor Rigby.”