MEET THE FESTIVAL VETERANS

I have enlisted the aid of a diverse group of filmmakers to share their festival experiences along with their advice. Each filmmaker and his or her work act as a case study demonstrating the dos and don’ts and the hows and the whys of the world of festivals and independent filmmaking. All have reached the end of their festival journeys with one or more projects finding lucrative distribution deals, a moderate release on cable and DVD, or self-distribution—but you never would have guessed how they got to where they are now. By taking a truthful and sometimes painful look at the paths they chose, the group you are about to meet prove that a healthy dose of self-criticism allows filmmakers to grow as artists. What you are about to read seem less like interviews and more like confessionals—each person offering a detailed account of his or her triumphs and failures.

I carefully selected interview subjects who would avoid being diplomatic and offer useful information to filmmakers and festival-goers. These interviewees constitute the best and the brightest in independent film. Each person delivers the real deal—hard information, free of polite spin.

The filmmakers interviewed for the fourth edition of this book have created a wide range of films, including shorts, documentaries, and narrative features. The subject matter touches on everything from social issues, to the music of Kurt Cobain, to video game obsession, to a musical real estate comedy, to a zombie mockumentary, to a documentary exploring the effects of fast food, to the misadventures of a likable nerd in rural America. The movies are as diverse as each filmmaker. Each of these movies represents one of the numerous paths a filmmaker can take when seeking success through a film festival. Some of these paths include:

Submit to Sundance, make it into Sundance, screen at Sundance, sell film for theatrical distribution.

Submit to Sundance, make it into Sundance, screen at Sundance, sell film for theatrical distribution.

Get rejected from Sundance, play another festival like SXSW, where the movie is then discovered and sold.

Get rejected from Sundance, play another festival like SXSW, where the movie is then discovered and sold.

Get rejected from every top-tier festival, only to become a hit on the smaller film festival circuit.

Get rejected from every top-tier festival, only to become a hit on the smaller film festival circuit.

Get rejected from almost every festival, go home empty but filled with hard lessons.

Get rejected from almost every festival, go home empty but filled with hard lessons.

Get rejected from nearly every film festival on the planet, seek self-distribution as the final option.

Get rejected from nearly every film festival on the planet, seek self-distribution as the final option.

There are certainly more roads than those mentioned and new ones that filmmakers will invent for themselves out of necessity. And whether you are making a short, a documentary, or a feature, you’ll find something to be learned from every type of filmmaker. Look to them for their inspiration, entertainment, and enlightenment, but most of all, learn from their experiences.

MORGAN SPURLOCK

Documentary filmmaker

FILMS: Where in the World Is Osama Bin Laden?, Super Size Me, 30 Days

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened films at Sundance, SXSW

AWARDS: Winner of Sundance’s Best Director prize in Documentary Competition, Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary

DEAL: Super Size Me sold at Sundance for $1 million

“Know what you want to achieve, and picking the right fest for your film will be easy.”

West Virginia native Morgan Spurlock did not exactly burst onto the scene, but looking in from the outside it just might seem that way. His documentary feature Super Size Me was the hit of Sundance 2004 and propelled him into the spotlight with his hilarious issue-based doc dealing with fast food’s impact on obesity in America. The always-smiling Spurlock is like Michael Moore without that chip on his shoulder. He’s a filmmaker on a mission, and his debut feature secured his spot in independent film history. His success continues with the FX reality series 30 Days and as a producer on projects such as Chalk and What Would Jesus Buy? His latest feature, Where in the World Is Osama Bin Laden?, premiered at Sundance, but what everyone wants to know is, where did he start?

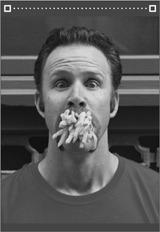

Morgan Spurlock

(Photo: Ari Gerver)

I grew up in West Virginia. My parents rule—they were always encouraging and basically let me pursue whatever creative outlet I wanted. If it wasn’t for them, I’d probably be handing out mints and towels in a bathroom somewhere.

When I graduated from high school in 1989, I went to USC to try to get into their film program. Because that’s what you do, right? I was accepted into their Broadcast Journalism department and thought that once there it would be easy for me to get into the film school. Boy, was I wrong. I was rejected five times! I applied every semester … and got rejected every semester. The last time I also applied to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and in their infinite wisdom they accepted me into the undergrad program. So, in the summer of 1991, I left L.A. bound for New York and the promise of a filmmaking future.

I graduated in 1993 and began working in the industry immediately. I did anything and everything. I shoveled shit on the set of The Professional, but I also got to shoot the last frame of film for the movie on the roof of the Essex Hotel with director Luc Besson. I got yelled at by pedestrians while holding traffic in Times Square on the set of Bullets over Broadway, but I also got to see and hear Woody Allen direct actors. I fetched coffee and fruit and danishes during the rehearsals for Boys on the Side.

While on the film Kiss of Death in 1994, I got a friend of mine a job working for Tracy Moore Marable (one of the coolest people on the planet) in the casting department. A few weeks later, they sent me to go audition to be the national spokesman for Sony Electronics. I had no agent and I hadn’t auditioned in years—not since my stand-up years at USC and NYU. What were they thinking? I ran downtown to drop off some film and on my way back to the office I ran in and auditioned. Two weeks later I found out that I got the job and was off traveling the country, far away from the schlepping and fetching.

Once on the road with Sony, I put my film degree to work by creating and shooting videos for them while also doing a lot of on-camera announcing for both them and their partners. Meanwhile, I kept directing and I kept writing. For Sony, Hasbro—any client that would pay me.

In 1999, my full-length play, The Phoenix, won the Audience Favorite Award at the New York International Fringe Festival; it then won the Route 66 National Playwright Competition. However, I also had the worst music video directing experience of my life that same year—and it was that spark that lit the fuse for me to start my own production company.

In 2000, The Con was formed, and our first show, I Bet You Will, blew up on the Web. It received more than 48 million unique visitors in eighteen months, and news stories were written about it worldwide. CBS optioned the idea—our worries were over. Then 9/11 happened and business in New York fell apart. I couldn’t find any work, I was evicted from my apartment, and had to sleep on a hammock in my office. I maxed out all my credit cards to feed employees, pay rent, and pay other credit cards. CBS dropped the option. It was the worst of times. I was more than $300,000 in debt and the bottom seemed to be getting closer every day.

Then MTV called after seeing us on Sally Jesse Raphael and bought the show. It went on to become the first program ever to go from the Web to TV. In 2002, we produced fifty-three episodes for the network and when the show was cancelled in October of that year, I decided to take the small pile of money we made on the show and make our first feature. That was the foundation for Super Size Me. The film went on to win me the Best Director prize in Documentary Competition at the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.

What’s my point in telling you all this? First, you can never dictate nor envision what ultimate path your career will take to get you to the “promised land.” Also, even when I was doing the crappiest of jobs, I realized that it was merely a piece of the bigger whole and that it was only on small step of a longer journey. I’ve known countless talents over the years who have given up on their dreams. Be true to you, stay the path, keep working, and you will reap the rewards.

Also, I was talking with a sales team early on in the process. My company was already repped by John Sloss’s law firm, so it was only natural that we would also go with his sales company, Cinetic. There are plenty of reputable companies that can represent your film to buyers, and having them come on early to start the ball rolling, lobbying on behalf of your film, is also a huge plus.

Don’t put all your eggs in the Sundance basket—there are countless fests around the world that may also be perfect for your film.

Do your research, talk to other filmmakers, get the lay of the land. I spoke to countless “alumni” about their experiences and asked what, in their opinions, we should do to guarantee the best Sundance experience possible. Everyone had a different answer and everyone was quite helpful in opening my eyes to the path we needed to be on at the festival. If you’re applying to the festival, first you should make sure the film you’re sending in is a good representation of the final product. You don’t need to send a finished film—we sent a rough cut, but at the time I would say the movie was about 85 percent there. Also, don’t put all your eggs in the Sundance basket—there are countless fests around the world that may also be perfect for your film. We kept sending the movie out. For me, I just wanted to get the movie out there for people to see. Anywhere.

There are festivals that are prestigious, fests that have markets and enable you to interact with global buyers, fests that are key outlets for up-and-coming filmmakers, and there are fests that are all about taking a vacation. Know what you want to achieve, and picking the right fest for your film will be easy.

You have to realize that as much as your film is art—it’s also a product. They key to every product is developing and building the brand.

Having a plan in place will help you put together a cohesive strategy. You have to realize that as much as your film is art—it’s also a product. The key to every product being successful is developing and building the brand. It was my goal to make brand Super Size Me one of the most talked about at the festival. So, TC:DM and I discussed ways to get the word out. Luckily, we had hit upon a subject that most of America was passionate about. But that didn’t mean our work was over.

Here were the pieces of the Super Size Me marketing puzzle and what each meant to me and the film.

BRANDING ONE: THE POSTER. We made posters prior to the festival that reflected the subject and were engaging (see the “Fat Ronald” poster). This is a key piece of your marketing material.

BRANDING TWO: THE SWAG. We also made Super Size Me skullcaps that we gave to key festival personnel—theater volunteers, parking attendants, etc. The more places your can get the name of your movie the better.

BRANDING THREE: THE TAKEAWAY. We made postcards that we put in restaurants, the press office, bars—anywhere that they would let us. The Fat Ronald was a natural pick since that was our poster, but the “Fry Mouth” was an afterthought. I had done a session with photographer Julie Soefer—a brilliant New York City photographer who helped out on the film—to get some publicity photos for the film. This picture came out of that session and quickly became the poster-boy image for the movie. My advice to you is to have a photographer take publicity stills for your movie that reflect the film’s theme. These will be staged and will deliver exactly the effect you want. It turned out to be a greatest visual tool.

BRANDING FOUR: THE PROMOTIONAL ITEM. Create something else that gets the word out in an original way. We chose buttons since everyone in Park City loves to wear them—on their jackets, hats, lanyards, you name it. We made 1,500 Obesity buttons (designed and created by NYC artist Syntax)—everywhere you went, you saw someone rocking the button. It was great branding for the film, and it helped build the buzz around it.

BRANDING FIVE: THE GIFT BAG. We wanted to take care of all the volunteers and media personnel who had taken care of us. This is such a great thing to do because these guys all bust their asses for nothing and are the biggest buzz generators when it comes to your movie. We made “Unhappy Meals”—printed paper bags that were filled with goodies that related to the movie and supported the Super Size Me brand. We made 250 Unhappy Meals, each containing a CD with the movie’s theme song (which we burned and labeled ourselves), a postcard from the film, a skullcap, either a burger phone book or french fry coin purse, and a key chain. People loved these Unhappy Meals, and being one of the filmmaker who remembers these hardworking folks goes a long way.

BRANDING SIX: THE STREET TEAM. Everyone who worked on Super Size Me worked for free. So, as soon as we were accepted into Sundance, I told them all that I would take them. Now I had to pay to get nineteen people to Park City! Me and my big mouth! Luckily, once your film gets accepted into the festival, you have something of tremendous value. I called some producer friends of mine, Heather Winters & J. R. Morley, and hit them up for an investment. They had invested in many film projects in the past, and I thought this was right up their alley. After seeing the movie, they were onboard. They would get their money back first after the sale plus a percentage on top of that as well as an executive producer credit—in return, I would be able to take the whole team to the festival. A fair trade any day of the week in my book.

Now, why is this so important? Because once you get to the festival, you realize how overwhelming it would be to have to do everything on your own. Not only did I have my whole production team there, but now I had nineteen volunteers whose sole job would be to help promote the movie.

I had a wardrobe supervisor friend of mine contact Ride Snowboards, who graciously donated jackets to outfit Team Super Size Me. You couldn’t walk down Main Street without running into one of our team members. And they always had a pocket with postcards and another filled with buttons. Having all of them there definitely got the word out quicker and enabled us to accomplish more in less time.

-

BRANDING SEVEN: THE SUPER-SECRET SPECIAL SWAG. I wanted to make something up that only a few very special people would get at the festival. I called a friend of mine in China and had him find a manufacturer who could make these Fat Ronald dolls.

We only made a hundred of them and they became one of the hottest “must have” items at the festival. The drawback: Since I had to have them sent overnight air from China to ensure they made it to the festival, I spent more on the shipping than I did on the dolls!

Super Size Me poster art

We were all in agreement that Dave Magdael was the best choice, and we scheduled a face-to-face meeting immediately. Dave is a great contrast to my personality. He is a very calm person. For me, especially in the heated madness of Sundance, I was ecstatic to have someone behind me who never got frazzled or bent out of shape. He and his team were so focused and they definitely maximized the exposure of both our film and me as the filmmaker.

Second, the company had to be as passionate about the film as I was. The company we ended up going with, a tag team release with Roadside Attractions and Samuel Goldwyn, was everything I wanted.

They were passionate, they were persistent, and they got the film completely. They were also the very first company to come forward and make an offer. Being first to the dance is something I put great value in because it shows they are thinking for themselves and not just following other companies or the press.

Morgan Spurlock

That was a tremendous accomplishment. Overwhelming, actually. When I heard the news, I jumped and screamed and yelled and ran around the office. The little guy had won, and Goliath was backpedaling.

So to all you filmmakers out there who think that what you say isn’t important or who feel that what you do cannot make a difference … guess again. You work in the most influential and powerful medium in the world—your actions can move mountains and your images can inspire generations to come. Don’t stop working. Persistence. Dedication. Time. And belief. These are the foundations of success, and these will help you change the world.

AJ SCHNACK

Documentary filmmaker

FILMS: Convention, Kurt Cobain: About a Son, Gigantic

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE:Screened films at Sundance, SXSW, Toronto, and forty others

AWARDS:Independent Spirit Awards nomination DEALS: Balcony Releasing, Cowboy Pictures

“… once you’ve made some films, you begin to realize that there are all these people who have made their way without having Sundance shine its light upon them. So look down the line to the next festivals—SXSW, Berlin, Hot Docs, Rotterdam, SILVERDOCS, Los Angeles, etc.”

AJ Schnack grew up in Edwardsville, Illinois, a small town just outside St. Louis. In grade school he knew he wanted to make movies, but there was no direct route from Edwardsville to working in film. He studied journalism at the University of Missouri, but, two weeks before graduation, he moved to Los Angeles and got a job working in game shows for titans like Dick Clark and Merv Griffin. AJ then got involved in music videos, starting a production company with his partner, Shirley Moyers. They did more than a hundred projects over a five-year period. During that time, he made the feature-length documentary Gigantic about his friends Flansburgh and Linnell (the two Johns behind indie band They Might Be Giants).

AJ Schnack

AJ tells us about Gigantic and his critically acclaimed doc Kurt Cobain: About a Son, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.

Kurt Cobain: About a Son poster art

I talk a lot about not getting wrapped up in a single festival, and let’s be honest: The unnamed “single festival” is almost always Sundance. There are reasons why Sundance gets all the attention, not least because it’s a name brand—even your Grandma has heard of Sundance—and because of all the stories of people finding fame and fortune there. But, once you’ve made some films you begin to realize that there are all these people who have made their way without having Sundance shine its light upon them. So make a great film and then look down the line to the next festivals—SXSW, Berlin, Hot Docs, Rotterdam, SILVERDOCS, Los Angeles, etc.

About a Son was very different. We submitted a pretty finished cut to Toronto, right at their deadline. Thom Powers, the documentary programmer there, saw it and called us pretty quickly to let us know that we were in. Then, because of the subject matter and because the film is such a nontraditional film about a rock star, we had a long, two-year-plus festival run, and in nearly every case, it’s been the festival requesting the film. After that, I don’t think we did very much in the way of submitting. It just became a film that was well known and well regarded on the festival circuit.

For About a Son, we worked with David Magdael and his team when we premiered at Toronto. I don’t think you can reasonably go to Toronto or Sundance without a good publicist who understands that landscape. It’s just way too big, with too much going on—both for you as a filmmaker as well as for people who are writing about film. You need to have someone who can be your liaison.

For Gigantic, we had a harder time getting people to come to the screening at SXSW, because frankly it’s harder to get distributors to come to screenings in Austin. It’s not known as a marketplace in the same way that Park City is. So after SXSW was over we had a screening in New York City that some distributors, including Gary Hustwit from Plexifilm, came to. Gary wanted to acquire the film for DVD. Shirley and I really wanted Cowboy Pictures to distribute the film. And Cowboy and Plexi had just worked together on the documentary I Am Trying to Break Your Heart. So everything ended up coming together, and that became a great partnership.

On About a Son, we had a lot of people working. Jared Moshe, one of the producers at our partner company, closed a deal with a Japanese company right after we premiered. Our U.S. sales rep was Josh Braun, and he pulled together our DVD deal and our cable TV deal. I reached out to my friends Connie White and Greg Kendall at Balcony and we worked out a deal with them to handle theatrical distribution. And our music supervisor, Linda Cohen, got us a great soundtrack deal with the Seattle indie label Barsuk Records. Meanwhile, we had a foreign sales agent who got us deals in the UK, France, Australia, Mexico, and a bunch of other countries. Even though that film was a difficult sell, it was hard to keep track of everything that was going on.

None of these deals were for a ton of money. A couple of the elements of About a Son were low six figures, which was great, but not anything that gave us as filmmakers a big return.

I’ve been surprised both with Gigantic and with About a Son as to how much work fell to me during the festival and theatrical runs. And a lot of times, people just expect that you’ll work for free, because it’s your film and you want to get it out there. Of course, you do want to get it seen, in the proper context and with the right DVD extras and marketing and trailer. But unless you’ve been acquired by someone with deep pockets, you have to stay on top of all of that—without much in the way of payment—if you care about that side of the process.

I’ve seen a lot of filmmakers respond to critics over negative reviews, and it almost always makes the filmmaker look bad.

Other than that, be friendly. Be yourself. Be charming. Don’t be a pain in the ass.

PAUL RACHMAN

Documentary filmmaker

FILMS: American Hardcore, Four Dogs Playing Poker, Drive Baby Drive

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened films at Sundance, Palm Springs International, Avignon

DEALS: American Hardcore acquired by Sony Pictures Classics

“The best advice I can give is to make the best film possible, apply, and then forget about it. Go back to working on your film or just enjoying your life.”

Paul Rachman’s pursuit of filmmaking coincided with the music scene of the early 1980s. Heavily influenced by punk during his formative years, he went on to direct over one hundred music videos for Alice in Chains, the Replacements, Roger Waters, Pantera, and Kiss, among others. Paul then made Drive Baby Drive, a 35mm black-and-white thriller, which he also wrote and financed. The film was rejected by Sundance, so in 1994, Paul joined forces with Dan Mirvish, John Fitzgerald, Shane Kuhn, and Peter Baxter to organize the Slamdance Film Festival—Anarchy in Utah. This guerrilla film festival was created as a protest to point out how commercial the Sundance Film Festival had become. In 1999, through the help of an agent, he was hired to direct his first feature film, Four Dogs Playing Poker, starring Forrest Whittaker, Balthazar Getty, and Tim Curry.

Paul Rachman

Paul talks about his festival experiences and how he got American Hardcore into Sundance.

The project was perfect for me at the time, and I really felt and understood the voice that this film could have. I also still had a lot of footage from back in the day that hadn’t been seen yet.

Steven finished the book in 2000. I proceeded to put a proposal together to try and raise some money. I took it around to all the usual suspects in independent film, people I had come to know through my years in L.A. and in Park City during the film festivals. Everyone said no. I could not raise a single penny or get the slightest serious interest from anyone. I guess it didn’t help that the cover of the book was an image of a kid with a bloodied face singing into a microphone. In that moment I said to myself, “Fuck the film business. I don’t need them to make this movie, just like the bands in American Hardcore didn’t need the music business to make and play their music.” That attitude and mandate gave me the energy and confidence to start shooting American Hardcore on miniDV in December of 2001.

By 2003, we had a twenty-minute work-in-progress, which we took to IFP (Independent Feature Project) in New York, and again we were not able to raise a single fucking penny. But the unveiling at IFP created a buzz in the punk world, and we knew we had an audience. We continued shooting and editing, and at the same time I relied on my editing experience to earn a living and finance the film.

After Thanksgiving in 2005 I went on a short vacation to the Dominican Republic with my fiancée (now my wife), Karin Hayes, who I met at Slamdance in 2003, where she won the Audience Award for her film Missing Piece, now titled The Kidnapping of Ingrid Betancourt and broadcast on HBO/Cinemax. On the last day of our trip I thought it might be a good idea to check the home answering machine for any emergencies. On the main drag of the dirt road beach town we went to a phone center just as it was closing, and there were two or three messages from Trevor Groth from Sundance telling me that they had accepted American Hardcore and that they were concerned that they hadn’t heard back from me yet, that the press release was going out and they needed to know ASAP. I was totally thrown for a loop—everything in my normal life at that moment changed.

I called Trevor back and before accepting I asked him if he knew who I was with regard to Slamdance. I wanted to make sure I wouldn’t be kicked out of Sundance the next day. At first he had no idea, then he put two and two together and realized it, but he assured me it did not matter because he loved the film and so did the other Sundance programmers. Before accepting I also asked for a Salt Lake City screening slot in addition to the Park City screenings because I felt it was important to bring the film down to the real punks in Salt Lake City. They agreed and I accepted.

Make the best film possible, apply, and then forget about it. Go back to working on your film or just enjoying your life.

If you get into Sundance, or Slamdance for that matter, and you have a little bit of buzz and a film that distributors want to see, then that becomes your most powerful asset. As a filmmaker going to a major film festival attended by major distributors who are there to buy, you must 100 percent believe in your film and its position in that market. Guard your premiere—the premiere will only have the impact you seek if it is a true premiere for the distributors. Most distributors want to see films before the festival to really just start crossing films off their list. That information, especially if it’s bad, sometimes travels within the industry—somehow word gets out through the network of acquisition executives and their assistants. The impact a film has when it’s seen with an audience of two hundred or four hundred people in a theater is totally different than when someone watches a DVD on his computer while answering e-mails and taking phone calls. This can be a deciding factor in the commercial life of a film.

It is very important to create a viable story for your film. That story is what is going to be communicated, repeated, and hyped by the film community. For American Hardcore the punk rock community was already buzzing about the film, but in reality that is a pretty insular and small community. We wanted American Hardcore to be more that just a DVD we would sell to punk rock fans. We had to find another way to “break” a more mainstream story about the film.

An incredible opportunity ended up presenting itself. A couple of days after the Sundance lineup was announced, Charles Lyons, a journalist friend of mine who regularly writes about independent film for Variety and the New York Times, called me because he needed help editing a reel. We decided to meet for lunch so I could get his materials. Over that lunch I mentioned to him that American Hardcore got into Sundance. His eyes immediately lit up and he said that that was fantastic and that there was a story there because I was a Slamdance founder and was going to Sundance. He asked if he could pitch it to the New York Times. I agreed, and on December 20, 2005, there was an article on the front page of the New York Times Arts section that had a picture of me and the headline “Sundance or Slamdance? A Rebel Director Gets His Pick.”

Within a couple of days that same story was picked up by AP, Reuters, and AFP and was basically reprinted in newspapers around the world. This was a month before the festival and was probably the most important thing that happened for the film in terms of setting it up. Phone calls kept coming from people who wanted to see the film, and there were more requests for interviews—all sorts of stuff started happening.

Not everybody has a journalist friend who happens to call for an unrelated favor and writes for the New York Times, but he saw a story there. Stories get picked up by wire services from newspapers all over the world, even small-town papers, so definitely try to think through these types of opportunities. Finding the story for your film—one that can be mainstream—is probably the best thing you can do to set up your film.

American Hardcore DVD box art.

Once we got to Park City, we followed up and also received calls for interviews from press that we had not yet been in contact with. We worked like crazy the six weeks prior to Sundance, and once we got to Sundance we were running from place to place, but we got a lot of coverage.

Now let me get back to the film publicity list and also dealing with the Sundance press office. There’s a constantly mutating list of journalists and press people with contact info that tends to get passed along and vetted within the independent film community. Most filmmakers who have been to Sundance or Slamdance and have relied on self-promotion have that list in some form. Getting a complete contact list for the press attending Sundance is the ideal, but it’s often an impossible task. I think the Sundance press office may have stopped handing it out to filmmakers several years ago after complaints from the press corps. So, instead, we worked from a list from the previous festival year that was not too out-of-date.

If you are going to do your own publicity, it is very important to have the Sundance press office recognize you as capable and professional. Karin was our designated publicist, and she was the only contact person for the Sundance press office and the press. She was very professional and organized, is a great communicator, and is incredibly charming and likeable—she is also my wife! These are very important qualities if you want to generate results during these twelve mad days of the film festival. The Sundance press office can be helpful in putting interested press in touch with your publicist, but for the best results, don’t rely on them for everything. It’s up to you to generate your own press.

There is also a sponsorship office at Sundance, which is helpful in finding companies wanting to sponsor parties and films. We did get a few beverage sponsors and some recommendations of venues from them.

Use all the power of the Internet and the network communities, such as Facebook, My Space, and Twitter, to reach out and create your audience.

Hardcore fans get tattooed with the name of the film.

We came into the festival with enough buzz that we felt we were getting a fair amount of attention. That was due to all the work we had done before getting to Sundance. It is very important to work as hard as you can on things you want to happen for you at Sundance way before you get on a plane to Park City. American Hardcore was not in competition at Sundance—something people do not realize. We were in the midnight film section. I think that was a blessing for the film—it took the pressure off of worrying about whether we would win an award. Also, the midnight section is actually one of the most successful in terms of making sales. The Blair Witch Project and Saw are both films that premiered as midnight films. Also, our film was music related, so that automatically has a specific subsection of interest.

When ticket sales for Sundance become available online, buy as many as you can among yourself and friends that you know will attend.

The initial offers for American Hardcore were low. We still had a lot of the film to pay off, so we started to negotiate for better offers. It is very important to know your bottom line—the least amount you are willing to take—and keep that number close to your chest. We decided that we wanted a deal that would do no less than pay the amount we had invested in the film so far plus all the costs that we would incur to deliver the film to a distributor—35mm print, 5.1 sound mix, HD versions, and all the rights and clearances for the images and music, as well as all the legal and business expenses. While we shot and edited the film on a low budget, to deliver to a major distributor like Sony Pictures Classics you are essentially going to deliver a product that works with the studio system. They want a lot of paperwork and physical materials that can easily cost almost an additional $200,000, so no matter how cheap you make a movie, once you sell it to a major distributor those costs become very real. We were able to negotiate the price from high five figures to mid-six figures, which met our minimum requirements to cover the costs.

We accepted an offer from Sony Pictures Classics for five territories: the United States, Canada, Mexico, Germany, and Australia. We did not sign the deal until the end of March 2006, two months later. It sometimes takes a long time to negotiate these deals to the point of signing, and then the physical delivery starts. We did not see our first advance money until May 2006.

I remember when I toured film festivals around the world in 1994–2000. Film festivals back then had a lot more money, and now it has become harder to get much out of them, especially transatlantic flights, and especially if you have a short film. What I did was buy a ticket from New York to Barcelona—Spain was our first festival stop—and a return to New York from Oslo, Norway, our last film festival of the tour. All the travel and lodging in between was paid for by the different European festivals. If you can, try to organize this type of festival route. There are a lot of film festivals in Europe and Asia that will work this way, because it ensures their best chance of getting the latest festival films on the circuit. Again, go for press, hand out flyers, work with your local distributor if you have one. We tried and mostly achieved our goal of having at least one major interview or article in the biggest newspaper in each city we played.

To avoid a bad screening, make sure you do a very elaborate tech check with the projectionist who will be running your film.

A Sundance or Slamdance premiere is not the end all or be all of launches for a new film. There are several important festivals, and there are many European festivals, such as Berlin, and Edinburgh in Scotland, that program indie films and can attract distributors. In the United States, the opportunities are really opening up with various forms of self-distribution using the Web to reach out. More and more distributors will be looking at films that start breaking out that way.

SETH GORDON

Director, documentary filmmaker

FILMS: The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters, Four Christmases, Suicide Squad

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened films at Slamdance, SXSW, Seattle, Fantasia, Newport Beach

DEALS: Sold the doc-version remake rights for The King of Kong to New Line

“Don’t make it ‘more commercial’ don’t ‘dumb it down’ don’t guess what buyers will like.”

Seth Gordon discovered film while working as a teacher in Kenya during his escape from college. An admitted video game fan, he caught the documentary film bug after capturing a series of unexpected events with his Hi-8 camera during his stay in Kenya. From that experience, he learned to love documentary storytelling.

Seth Gordon

Seth tells us about his journey from the arcade to Slamdance to theatrical distribution for his amazing video-game documentary, The King of Kong.

I never thought our film was especially important and was just doing it for the love of the topic, not for the politics or the need to inform. I think that allowed us to focus on Steve and Billy’s personal story, which ended up being the point. I don’t particularly like issues films and never wanted ours to be one.

Still from The King of Kong

We couldn’t afford a publicist, but Endeavor helped with some of those duties because they have those connections, and they arranged for the early screening. Publicity never came up before the eventual theatrical release of the film the next fall.

The King of Kong poster art

What did you look for in the deal?

The advance is the only thing that matters and very likely the only money you will see.

LINCOLN RUCHTI

Documentary filmmaker

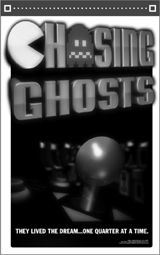

FILMS: Chasing Ghosts: Beyond the Arcade

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened at Sundance, Los Angeles Film Festival, Austin Film Festival

DEALS: Sold Chasing Ghosts to Showtime

“Our main mistake was taking the competition a little too lightly.”

Lincoln Ruchti, the director of that other video-game documentary, talks bluntly about the Sundance premiere of Chasing Ghosts and having to deal with unexpected challenges.

Chasing Ghosts poster art

Regarding festival hype, much of that was built in for us with our subject matter. We were moving people through the arcade, but we didn’t feel like it was generating enough buzz for the film. So we adopted our strategy. I went to Wal-Mart Park City (cozy little mom-and-pop) and bought a Hula-hoop, some felt, and a bunch of other supplies and created a Pac-Man costume that my buddy Chris could wear to promote the film. I think it actually got the word out better than the arcade. I wish we’d come up with that idea sooner.

Pac Man walked the streets of Park City to promote Chasing Ghosts.

By far the best experience was my overnight trip to Skywalker Ranch, care of the L.A. Film Festival. There is so much hype built up about the place, and I don’t know if it’s all projected or what, but when you get there it feels special. Like a retreat, only you mix a movie between horse rides and mani/pedis. They were mixing Into the Wild when I was there. Sean Penn ducked out when we all walked in.

JEREMY COON

Producer

FILMS: Napoleon Dynamite, The Sasquatch Gang, Humble Pie (aka American Fork)

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened films at Sundance, Slamdance, SXSW, London, U.S. Comedy Arts Aspen, Nantucket, Sidewalk, and more than forty more

AWARDS: Nominated for Independent Spirit Awards, won MTV Movie Award for Best Movie, and too many more to list

DEALS: Sold Napoleon Dynamite to Fox Searchlight for $4.7 million

“People’s reactions to films are largely based on expectations. You want people just aware of enough of the film so that there are butts in the seats, but you don’t want expectations so high that they leave disappointed.”

Jeremy Coon is a native Texan and graduated from BYU with an undergraduate degree in film and an MBA. He’s produced several feature films to date. The first (Napoleon Dynamite) you’ve probably heard of; the second (The Sasquatch Gang) you might have heard of; and the most recent (American Fork [aka Humble Pie]) you may never have heard of. All three are independent films that played the festival circuit extensively. Jeremy is unique as a producer since he also performs double duty as a highly skilled editor. He became a film buff at the age of seven when his dad took him to see Aliens in the theater, and he’s been hooked ever since.

Jeremy Coon with actor Jon Gries

Jeremy talks candidly about the making of Napoleon Dynamite and its sale at Sundance, as well as the fate of his other independent film projects, plus the scoop on Napoleon Dynamite Part 2.

Jared and Jersuha (his wife) worked on the script and I moved out to L.A. to get things rolling out there. My original career goal was to be an editor. Producing was something that I started doing in film school because no one was very good at it and I knew I could do a better job. On Napoleon, I felt the worse case was I would have my first sole feature editing credit. Jared and Jerusha’s first draft of Napoleon was about seventy-five pages long, and it was great, but it got punched up with a couple of more revisions. We got the funding we needed, had a great script, and just set out to make it the best way we could and learned a lot along the way.

Develop a relationship with a programmer or find someone who already has one, and have them talk directly about your film, even if it’s a non-business-related connection, like their hair stylist.

The best way to ensure your film gets accepted is to submit the most complete version of the film you can and submit it as early as you can. If you submit something that’s too rough too soon, the stigma of that first rough cut will likely stick, so be cautious. The earlier you submit it, the less slammed the programmers will be and more of them will have a chance to watch it. Other than that obvious hint, the next best alternative is to either develop a relationship with a programmer or find someone who already has one, and have them talk directly about your film, even if it’s a non-business-related connection, like their hair stylist. Any personal connection, no matter how small, definitely helps. After the conversation, you can submit your film directly to their attention. Adding this personal qualifier will separate you from the masses and ensure that your film will get considered under the best of circumstances—but again, nothing will ensure acceptance.

As far as packing the screenings, we didn’t have to do much of anything. All of our screenings sold out almost immediately. Part of that is that we had more of a local presence than other films, but I know plenty of friends who were unable to get tickets. The biggest reason for the demand is probably the terrific synopsis that Trevor Groth wrote for the Sundance program. It was so glowing and nice that it was as if one of our mothers had written it. The majority of people are going to base their decision to see a film or not off of the program, so make sure you’re happy with your description and photo in the festival program.

A good publicist can help make the most of the situation, but how audiences ultimately react to your film is largely outside of a publicist’s control.

Generally, I have mixed feelings about publicists. There are a handful like Jeff who really add value because they have connections and their opinions are well respected. I’m sure this is going to offend some publicity peeps, but I think most are overpriced and often get more credit than they deserve. Some publicists really just manage incoming requests, which really anyone could do. If you have a hot film, journalists will want to do press for it, but if you have a dud, they don’t. A good publicist can help make the most of the situation, but how audiences ultimately react to your film is largely outside of a publicist’s control. For festivals other than Sundance or Toronto, I would not hire a publicist and would save your money for other expenses if money is tight.

Napoleon Dynamite poster art

We easily could have sold Napoleon to another distributor for likely more money, but if the release was botched we would have lost in the long run, both financially and for our careers.

If you have a good offer on the table and you don’t have a fallback option, be careful of negotiating too aggressively. It might backfire on you.

There are way more reasons to not buy a film than to buy one, and the longer a distributor thinks about it, the more likely they are to talk themselves out of buying. It doesn’t take much negativity to turn the tides within a company. Once that marketing department saw Sasquatch, they felt that it didn’t have enough big-name talent and they didn’t want to (or couldn’t) put in the effort to create a unique campaign like Searchlight did with Napoleon. That response all but killed the deal for us. So again, don’t get too caught up in the hype. If you have a good offer on the table and you don’t have a fallback option, be careful of negotiating too aggressively. It might backfire on you.

The other moment was when the actual sale of Napoleon was closed with Fox Searchlight. We knew we weren’t going to accept any offers until after the third screening. Napoleon had its first screening at 5 P.M., then 11 P.M., and then 11 P.M.the next day, so we had a majority of our screenings within an eighteen-hour period. We knew the screenings were going extremely well but had no idea what it meant. After the third screening, John Sloss (the head of Cinetic) invited Jared and me up to their condo to discuss the offers. We sat around for about an hour or two and nothing was going on. I was wondering why we were just sitting there chilling. I’ll admit I was a little worried for a brief time. I realized later on that John just wanted Jared and me out of sight so that no distributor could ambush us. Selling a film at Sundance is a total game, and John is very good at it. The first offer came in from MTV Films for $3 million. That was when I realized that something really special was going on. The most I had even hoped to sell the film for was maybe $3.25 million and now I knew our floor was $3 million and we could use that as leverage against other distributors.

The next two hours was a flurry of activity. We were basically down to two distributors very quickly: Searchlight and Warner Independent. We had an appointment with Warner, but Searchlight was first and told us that they all had to go to the screening of The Motorcycle Diaries in two hours and were leaving with or without the film. Peter Rice and the entire executive team came to the meeting, and each department talked to us about how they would handle the film. After that we went into separate rooms while John Sloss ran back and forth with the offer as we negotiated and ended up with $4.75 million. As we were closing the deal, Warner was driving up the hill to the condo and we told them what the price was at and asked if they wanted to go higher. They thought we were bluffing and turned around—and we closed the deal with Searchlight. It all happened so quickly that it took a while for it to really sink into us. I totally understand now why people get emotional after winning a championship or a gold medal. After so much time and work, it’s almost an emotional overload to actually get what you’ve strived for, for so long.

On Sasquatch, we wanted to work with more established forms of financing from production companies because the budget was higher this time: $1.35 million. We felt it would be an easy sale to get someone to put up the money after the success of Napoleon and wanted to capitalize on that. On my third film, American Fork, we went back to a single private wealthy investor. I’ve been fortunate enough that I haven’t had much of a problem raising money for films. Again, I know that’s not interesting or probably useful. Once you get your first one down, raising money usually gets easier with each subsequent film. The best advice I would give is find someone who is excited about the film and then get them excited about your vision for it. I’m also a firm believer that almost any film can get made on any budget if you can get creative enough.

The investor needs to be prepared to lose 100 percent of their investment.

Producer Jeremy Coon (at left) with the cast and crew on the set of Napoleon Dynamite

That said, most people invest in a film mostly for reasons other than financial, so focus on those. Things like helping a family member by giving them a shot (like I experienced), really believing in the script, or maybe a rich person would just like to experience visiting a set and vicariously being a producer. Those are elements you have control over and can guarantee. There is so much out of your control that helps make a film successful that if you invest solely based on an expected financial return, you’re bound to be disappointed.

There is no way to plan for the kind of success and attention that Napoleon received. It just happens and you deal with it. I think I realized that Napoleon had entered the cultural zeitgeist either when Napoleon Dynamite was used as a descriptive adjective in a New York Times article or when we got our own Trivial Pursuit question. One agent early on told us that Tom Cruise hosted a screening of Napoleon at his house for Will Smith, Jim Carrey, and some other celebrities, and they all loved it. Denzel Washington and Clint Eastwood are also both huge fans. That stuff seems so strange, but assuming it’s all true, that’s so cool. It still feels strange that so many people know about and love this little film we shot with a bunch of buddies in Idaho. Even all these years later, I still regularly meet huge fans that are excited to know anyone who worked on the film. I always try to be really thankful to fans, because they’re the ones that made our dreams come true by helping us have film careers.

We thought briefly about going the studio route, but at the time, I didn’t want to deal with the slow process, the politics, or risk losing creative control, especially with a first-time director. I think a director’s first film needs to be on a smaller budget so there is less pressure and no studio executive constantly looking over their shoulder. Directing your first film is hard, and if you’re not allowed to experiment, make mistakes, and learn from them, the film will probably suffer.

Directing your first film is hard, and if you’re not allowed to experiment, make mistakes, and learn from them, the film will probably suffer.

Again, I brought in Cinetic Media to act as our agent, but this time early on to find funding in addition to handling the distribution rights. Ultimately, we ended up partnering with Kevin Spacey’s Trigger Street Productions. They agreed to put up the money for the film and give us the creative freedom we were looking for.

Definitely think about what kind of audience you expect to dig your film, and then think about what audiences go to different festivals. A good starting point is looking at past films that have been accepted to various festivals and been well received there. This can also help you target and narrow your search for film festivals to apply to in general.

Slamdance is a very different festival and experience than Sundance. It’s much smaller and the venue isn’t great, but the festival puts out a very cool energy and vibe. Basically, it’s more fartsy and less artsy compared to typical Sundance films. As far as our strategy, we wanted to have a presence in Park City so distributors could see the movie but wanted to keep a low profile so if the screenings didn’t go well, we wouldn’t be DOA. If Sasquatch failed to connect with audiences at Slamdance, it could do so quietly, and if it hit, we could get some traction for a deal.

The hard part was getting busy distributors to head up to the film’s screening at the Treasure Mountain Inn. Knowing that, we did one screening in L.A. and one in New York about a week before the festival. Tons of distributors showed up to each screening and we packed the theater with kids who were the exact demographic for the film. We even invited distributors to bring their families and children. This way the distributors were seeing it with a real audience and not a stuffy industry-type crowd. We were able to generate a lot of interest and awareness for the film so that by the time the festival started we were on a lot of people’s radar and not lost in the shuffle of the hundred-plus films playing.

We ended up selling the U.S. film rights to Sony BMG Films for less than $1 million and divided up the international rights to make the most of each territory. It was much more work and for less money than Napoleon. Sony BMG sat on the film for a while and the label ended up being shut down. So the film sat on the shelf for over a year until it was sold to Screen Media and finally released in November 2007. I’m still very proud of the film and just happy that it got released and is easily available on DVD. There are plenty of indie films that don’t even get to experience that moderate level of success. Who knows, maybe Sasquatch could even legitimately become a cult film as it’s discovered by more people on DVD.

Unless the distributor is going to really put some serious marketing money behind the film or have an ingenious plan, it’s probably best to forgo a theatrical release.

GRACE LEE

Director

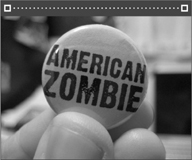

FILMS: American Zombie

FESTIVAL EXPERIENCE: Screened at Slamdance, SXSW, San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival, Visual Communications in Los Angeles, Hawaii, Sitges Fantastic Film Festival, Puchon Fantastic Film Festival, Singapore International Film Festival, Brussels Fantastic Film Festival

DEALS: Sold to Cinema Libre

Grace Lee

“Be open to requests from festivals you’ve never heard of. When I say be strategic, I mean study their programs and get a sense of if your film would fit in there.”

Grace Lee was born and raised in Columbia, Missouri, which is also home to the True/False documentary film festival. Grace tells us about her first feature, American Zombie, and ways to market a small indie.

The best thing to do is to have your film be completely finished. People are always trying to submit rough cuts or versions with temp music or unmixed sound, which puts you automatically at a disadvantage from films that are already finished and on the circuit and have even won awards. You may be able to see your masterpiece without the final titles and a properly mixed sound track, but that’s because you essentially saw your finished film when you were in the process of writing it.

You definitely don’t want someone to recommend your film if they are not enthusiastic about it.

Be strategic when looking at the more well-known festivals and where to premiere. But once that is out of the way, also be open to requests from festivals you’ve never heard of. When I say be strategic, I mean study their programs and get a sense if your film would fit in there. I know lots of people who just send their film to dozens of festivals at once and wait for any or all to respond. I think that’s a waste of time and money. I have sometimes contacted a festival I was interested in or even just curious about to describe my film. If it had been in a previous festival, I might mention that, or if it had won an award. In some cases, not all, the festival would invite me to submit the film and waive the fee. I could also tell by talking with a live human being whether it would be a good match. It can’t hurt to ask whether they might do that, but if they say no, then respect their policy.

I would have applied to more festivals or sent off the many requests for screeners, but as I mentioned before, the decision wasn’t mine to make. The company that financed the film ultimately made the decisions of where the film could play. Kind of a bummer since as a filmmaker I am all about people seeing my work, but we were dealing with another strategy here.

American Zombie button

Make sure you have people on your team who do enjoy calling attention to themselves to help promote the movie. Generally actors are pretty good at this and are used to having to sell themselves while making it all look effortless and genuine.

I’m a pretty low-key person and hardly an extrovert. I’m the kind of person who would rather talk to someone one-on-one while standing in line than take to the streets drawing attention to myself. So my advice is to make sure you have people on your team who do enjoy calling attention to themselves to help promote the movie. Generally actors are pretty good at this and are used to having to sell themselves while making it all look effortless and genuine. Take advantage of their energy and try to learn from it.

One thing I saw one of the actors do was pretty clever. This was in Park City, which is constantly teeming with people clamoring for access to the latest buzz-worthy movie. He would be in a crowd of people and start talking into his cell phone about how he had just seen American Zombie and how great it was. He did it loud enough so that people could overhear him and remember the title and even made sure he did it around people who looked like they might be executives or distributors. Who knows if it worked, but he seemed to enjoy doing it!

I think in general you figure out what is the bare minimum you need to realistically make the movie, taking into account the favors you will be calling in and making sure you are not insulting people for their time and talent. With a low-budget movie, it’s very important for me to be up front with people that it is low budget and the offers we make are the best they can be. When you are absolutely clear about this, people will lend their talents if they are interested in being part of the project. They certainly aren’t doing it to for the money!

Always be ready to pitch your idea-you really never know what people will like or be looking for.

Grace Lee and the American Zombie crew at Slamdance

Unless you are a lawyer or have loads of experience doing this by yourself, get a lawyer or producer’s rep onboard. I have no idea what most of the terms people are talking about mean or even refer to, nor do I have the expertise in negotiating something like this.

Well, IhQ is also the international sales agent. I know that there will be a small release in Korea, and I believe they are still working on others. I knew going in that I was signing away my rights to control many things I had been used to controlling because I wanted to get the movie made. Going forward, I’m more interested in the alternative distribution methods filmmakers are using to get their movies out there—whether it is self-distribution or teaming up with others to form a sort of traveling tour. But I would probably only work on a strategy like this if I knew that it would be part of the process and if it was appropriate for the film’s content. It takes so much out of you to make a film—and to have to switch gears and become a distributor is another two-year commitment (at least) that one needs to be aware of.

If you make a film that has an identifiable audience—be they documentary film followers, zombie aficionados, or horror fans—you have a responsibility to make yourself available to that outlet.

How did you support the release of the film after the festival tour?

Submit to Sundance, make it into Sundance, screen at Sundance, sell film for theatrical distribution.

Submit to Sundance, make it into Sundance, screen at Sundance, sell film for theatrical distribution. Get rejected from Sundance, play another festival like SXSW, where the movie is then discovered and sold.

Get rejected from Sundance, play another festival like SXSW, where the movie is then discovered and sold. Get rejected from every top-tier festival, only to become a hit on the smaller film festival circuit.

Get rejected from every top-tier festival, only to become a hit on the smaller film festival circuit. Get rejected from almost every festival, go home empty but filled with hard lessons.

Get rejected from almost every festival, go home empty but filled with hard lessons. Get rejected from nearly every film festival on the planet, seek self-distribution as the final option.

Get rejected from nearly every film festival on the planet, seek self-distribution as the final option.