Fifteen

Blue Dove

Glumly, I examine the sandstone hollow where we have made camp. Forty hand-lengths long, it’s barely ten deep. The ceiling is furred with a black layer of soot from a thousand campfires that have been built here over the long winters. Wind gusts continually push veils of rain beneath the overhang, drenching me and the fire. Even worse, just down the slope, I can see ruins appear and disappear in the pouring rain. A dismal place. The toppled walls resemble jagged black teeth. I imagine that they’re going to transform into an ancient monster and gobble us all up.

Tocho sits dozing in the rear of the hollow, guarded by FishTrap. Barely eighteen, he’s a gangly youth with arms and legs that seem way too long for the rest of his body. His face reminds me of a deranged weasel. Tiny slits of eyes stare out over a ghastly long snout of a nose. To make matters worse, he has a squeaky voice that grates on my nerves.

“What is this place?” I ask, looking around with distaste.

Wasp Moth sits cross-legged on the other side of the fire with Tocho’s bag in his lap. He’s been trying to untie the old leather laces since dusk.

“It was called GoingBuck Village. Your father burned it to the ground twenty summers ago for failing to turn over the tribute it owed Flowing Waters Town.”

“The fools. Why didn’t they turn over the tribute?”

“They were starving.” Wasp Moth shrugs and continues plucking at the laces on the pack.

“I should think that starving was better than being dead.”

“They were sure they were going to be dead either way, so they decided to fight.”

Shivering, I pull my cape more tightly around my shoulders. “Their chief must have been an imbecile. What sort of man would order his people to fight against overwhelming odds, knowing they had no chance to win? If they’d simply turned over all their food to pay the tribute they owed, the warriors would have left. Maybe most of the villagers would have starved, but surely a few would have survived. A few is better than none.”

Wasp Moth frowns at the old leather bag. “Is it? I think it’s better to die fighting for your people than to live as a coward.”

“You think my father was unjust when he demanded the tribute?”

“I didn’t say that. But surely the GoingBuck villagers felt the attack was unjust.”

“Tribute must be paid,” I say in irritation. “Without tribute, Flowing Waters Town can’t take care of people. We are the ones who stockpile food, and redistribute it in times of drought. It’s our warriors who protect them from raiders. How can we afford to do that if they don’t turn over part of their harvests?”

“Part, yes, but all of it?”

Indignant, I say, “It isn’t our fault that they had poor harvests that year. Do they think dying makes them heroes? Personally, I’d much rather be a live coward than a dead hero.”

Wasp Moth gives me a curious glance. “Dead heroes have honored places in the afterlife, Blessed daughter. The souls of cowards must walk the earth for eternity, condemned to regret and loneliness. I’ll take death any day.”

As though tired of speaking with me, he returns all his attention to the knotted laces.

I sigh and look away.

For as far as I can see down the length of the canyon, rain sheets from the cliffs. Runoff has turned the river into a murky thundering torrent. Less than a hand of time ago, I saw an entire cottonwood battering its way down the drainage.

“I can’t figure this out,” Wasp Moth says in frustration.

“Why not?” I glare across the fire at him. “Are you stupid? It’s a simple series of knots.”

Tocho leans against the canyon wall in the rear, watching with a bored expression on his face.

“I know they look simple, but they’re not.” Wasp Moth squints, and the stylized moth wings that spread across his cheeks scrunch into a chaos of indecipherable black lines.

“Give the pack to Deputy FishTrap. Let him try.”

Wasp Moth tosses the worn leather bag, and FishTrap catches it.

“It’s a tangle, no doubt about it, but looks easy enough,” FishTrap says.

“Just wait.” Wasp Moth leans back on his elbows and smugly watches as FishTrap begins to tug at the leather cords that tie the pack. As soon as he loosens one cord, another pulls taut. When he loosens that one, another tightens.

“Well, what the…”

“See?”

I scowl at Wasp Moth. “You’re to blame for all this, you know? If you hadn’t lost old Crane, who I’m certain is Maicoh, we’d have that bag open by now.”

“I swear to you, Blessed daughter, I only looked away from him for an instant, but when I looked back, he’d vanished into the night air like smoke.”

“The great Wasp Moth can’t even keep track of a frail old man. Some war chief you are.”

Wasp Moth looks angry, but doesn’t say anything.

I turn toward Tocho. The shaman is half asleep. He keeps dozing off and jerking upright again. When he notices me staring at him, he gives me a benevolent elder smile. Sparse gray hair frames his wrinkled face.

“What are you smiling at? Did you witch that pack?”

“I’m not a witch,” Tocho says mildly. “Just a shaman.”

“Why can’t we get it open?”

Tocho’s hands are bound together with yucca rope, so when he gestures it’s a little awkward. “Perhaps their fingers are too big. You might want to try. A woman’s smaller fingers are more dexterous, I think.”

I extend my hand to FishTrap. “Give me the pack.”

He swiftly hands it over, as though glad to be rid of it.

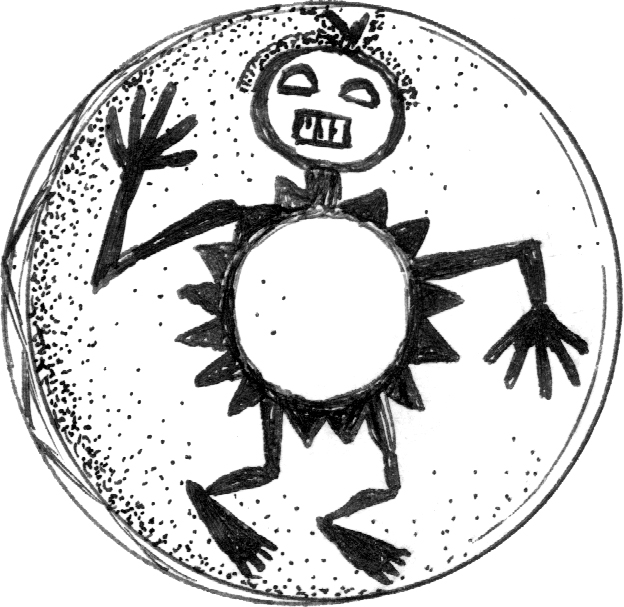

Placing it in my lap, I study it. It’s about two hand-lengths across, and the leather is worn so thin, anyone ought to be able to just rip it open and spill the contents on the ground. But that would risk damaging whatever is inside. When I tip the bag up to the dim light, I can make out the faded yellow and blue image of a tortoise on the front, or maybe it’s a wolf’s head. Actually, it could be both, one image superimposed over the other. Hard to say, but the bag is light as air. I knead the leather, trying to discern what might be inside.

“Feels like there’s a small pot in there.” I trace the globular shape with my fingers.

“I thought the same thing,” Wasp Moth says.

FishTrap nods in agreement, while Tocho naps in the rear.

When I shake the bag, it “tinks”—metal striking ceramic. “Why is it so lightweight?”

“Doesn’t make any sense.” Wasp Moth’s chin-length black hair shimmers in the firelight as he leans forward to prop his crossed arms on top of his knees. “Even if the pot’s walls are as thin as a leaf, it should be much heavier.”

“Ten times heavier,” FishTrap says.

The laces have been whipstitched all around the square, then cinched closed at the top and tied into a series of what appear to be simple slipknots. As FishTrap noted, the knots look easy enough to untie. It’s just a jumble of loosely tied loops, but when I grasp one end of the cord and work it through the knot to loosen it, another part of the knot sucks up tight. After I’ve been working at it for a full finger of time, I order, “Wasp Moth, give me your knife.”

He smiles knowingly. “Of course, daughter of the Blessed Sun.” Pulling it from his belt, he hands it over.

I start sawing at the base of the knot. “How on earth…”

Wasp Moth smirks. “You’d think those leather cords were made of pounded meteorites, wouldn’t you?”

“But they’re not. They’re old as the hills and brittle.”

Every head in the shelter swivels to look at Tocho, who is now snoring softly. His head is leaning back against the red wall, and his mouth hangs open. He’s sound asleep.

“Hey!” I shout.

Tocho jerks awake and stares wide-eyed at me. “What’s wrong?”

“Why can’t we open this bag?”

Through a long yawn, he replies, “It belonged to Nightshade and I think she enchanted it.”

I lift a skeptical eyebrow. “You’re lying.”

“I swear to you that’s the story I heard.”

“Have you ever actually seen what’s inside this bag?”

“No.”

Lifting the bag, I shake it at him. “Are you telling me the pot in here could be an ancient shit pot?”

“I suppose.” He shrugs, closes his eyes, and leans his head back against the sandstone wall. “But it does have a voice, and claims to be Nightshade, so I think it’s her soul pot.”

I squint down at the faded designs on the bag. As the light shifts, the shapes change. Now I see a wolf’s head with four tortoise legs around it. Placing my mouth against the leather, I shout, “Old witch, can you hear me?”

The bag is silent.

The rain outside falls harder, obliterating the view of the canyon entirely, and the earsplitting roar of the river shudders the ground. The raging current must be tearing up more trees and hurling them down the channel.

“There are no voices in there, you withered stick of an old man.”

“No?”

“No!”

Tocho’s nostrils flare with an exhale. “Well, that’s unsettling. I’ve been hearing her for many summers.”

“You’re a thousand summers old. You probably hear voices in every grain of sand.”

The old man leans forward with a quizzical look on his ancient face and whispers, “Are you saying grains of sand don’t have voices?”

Heedless of the fragile pot that might be inside, I hurl the bag to the ground near the fire pit, where it lands silent as a feather.

Wasp Moth and FishTrap glance at the enchanted bag, then at Tocho, and keep their mouths shut.

Glaring at Wasp Moth, I ask, “Did you hear a voice?”

Wasp Moth sits up straight. “I … well … I thought I heard … something.”

“What?”

“Might have been a woman’s laughter, but it was so faint it could have been anything. Maybe just the rain beating down. Or even the fire hissing.”

In the rear of the shelter, Tocho still has his eyes closed, but I see a small smile turn his lips.

I kick the bag with my sandaled foot. “You don’t scare me, old witch. I’m the daughter of the Blessed Sun. I can call down the entire might of the Straight Path nation on you.”

Both Wasp Moth and FishTrap shift nervously.

“What’s the matter? Did she speak to you?”

Wasp Moth quickly shakes his head. “No.”

“What about you?” I turn to FishTrap.

The warrior seems to have lost his senses. He looks like a bug with gigantic brown eyes.

Snatching up the bag, I hold it to my ear again. I hear absolutely nothing, but across the fire Wasp Moth’s face slackens and goes pale. The black moth wings on his face stand out sharply against the ashen background. I swear, he looks like he might faint.

“What’s wrong?”

“The voice … sh-she told me…”

“What?”

“Nothing. I’m sure I just imagined it. With the heavy rain and the trees battering their way down the river, there’s so much noise tonight, I must be weaving words out of the wind and water. That’s all.”

FishTrap’s gaze slides to Wasp Moth and he stares at him in abject terror.

“Did you hear something, Deputy?”

When FishTrap shakes his head it looks like a muscle spasm. “No!”

“Blessed Spirits! Tell me what you heard.”

FishTrap shifts uncomfortably. “Well … I just … I may have heard … a few words.”

“What were they?”

FishTrap swallows hard. “She might have said … ‘you’re all dead.’”

Wasp Moth nods.

“You imbeciles. You’re imagining it. I didn’t hear a thing!” I slam the bag to the ground, and whirl around when Tocho chuckles.

“Did you hear her, old man?”

He tilts his head to the rainy darkness outside. “As of this instant, you have far more important things to worry about. He’s coming.”

“Who?” Fear tickles the base of my throat. I don’t like any of this. Enchanted bags, and people hearing voices that I do not. I believe in the old gods and the Spirits that haunt the land, but I grew up with a legendary witch, so I know that most witchery is a sham, just fakery and clever deceptions. When I was a child, Father used to capture witches and force them to teach him their skills. Father uses sleight-of-hand to make objects seem to appear from nowhere, and positions lamps and polished pyrite mirrors to create otherworldly reflections that resemble ghosts. He can even cast his voice to make it sound like it’s coming from a painted dance stick across the room. People’s imaginations breathe reality into all sorts of monsters and mysteries. That has to be the source of the “voice,” or I’d hear it, too.

On the other hand, I also know that some witchery is frighteningly real. Though I have never witnessed my father do such things, I have personally seen a witch call out and stop the hearts of every bird in the sky. The resulting shower of dead finches thumping down all over Flowing Waters Town was horrifying. I have also seen witches kill with a single word.

To Tocho, I say, “If you’re trying to scare me, old man, you can’t. I know every trick—”

From the darkness beyond the shelter, a man’s voice calls, “War Chief Wasp Moth? May we enter?”

Wasp Moth leaps to his feet as though grateful for the distraction. “Enter, Iron Dog. We’ve been waiting for you!”

Five men walk into the shelter. Four are White Moccasins. I know three of them, Iron Dog, Weevil, and Chick. I know the fourth warrior as well, but can’t recall his name. The fifth man has the hood of his blue cape pulled up. He stands at the edge of the shelter, gazing out across the storm-lashed canyon. At almost the same instant he turns to look at me, lightning flashes. The stunning white light sheathes his magnificent face, turning it faintly azure.

Dear gods, look at those blazing blue eyes.

The White Moccasins come across the floor, bow to me, and slump down around the fire, eager to get warm. They start talking in low voices, speculating on the status of Flowing Waters Town and the fact that they can no longer get messages to my father, the Blessed Sun. Iron Dog says it’s probably because the signal stations on the canyon rim have been obliterated after the attack on OwlClaw Village. Chick agrees that surely the Canyon People must have attacked and destroyed every station they could.

I listen halfheartedly, for my attention is riveted on the stranger. The albino. As he shoves back his hood I see a long white braid tumble over his shoulder. Pure white, not the dull shade of the aged, but the gleaming brilliance of winter snow. Truly, he is the most beautiful man I’ve ever seen.

When he notices my attention, his head tilts slightly to the left, as though he is evaluating me back.

“Who are you?” I ask.

Iron Dog rushes to say, “Oh, Blessed daughter, forgive me. I thought you knew. Your father sent a signal several days ago, telling us where to meet him. Your father hired him to find the witch’s pot. This is—”

“I am Maicoh, Blessed daughter.” The albino strides forward so gracefully, he might be walking on air.

“You are not Maicoh.”

Though, I have to admit, Maicoh is a master of disguise. Could this be the hollow-eyed old skeleton I spoke to in the cave in OwlClaw Village? Doesn’t seem possible.

He frowns at the old leather bag, then his eyes narrow, and he extends a hand to it. “You are fools for trying to open that Spirit bundle. Don’t you see the red and white symbols dancing in the air above it? I’m amazed any of you is still alive.”

I glance at the old bag, then back at him. “How do you know we tried to open it?”

“Are you deaf? I could hear her screaming in rage and cursing you from halfway down the canyon!”

Wasp Moth and FishTrap both stiffen at the mention of a curse. All around the fire, warriors exchange unsettled mutters.

The albino kneels beside me, and his blue cape spreads over the floor like a flood of midnight sky. He gestures. “May I hold it?”

“Take it. I’m sick of it.”

In the rear of the shelter, Tocho laughs softly.