Thirty-six

Blue Dove

Kites wheel in the sky as I step off the pithouse ladder and look around Flower Moon Village. No one even glances in my direction, and that’s a curious feeling. If I were home in Flowing Waters Town, dozens of people would leap up at the sight of me and rush to tend to my needs. But here, in this squalid collection of ten pithouses, people in tawdry capes don’t even notice, they just continue going about their afternoon duties. The golden cliffs that hug this valley appear amber in the slanting rays of sunlight, but shadows are lengthening as Father Sun descends toward the western horizon.

Staggering down the sloping side of the pithouse proves how sick I still am. Though I slept most of the day, my weak legs barely hold me up. Once I hit the flats, I stumble my way through the village.

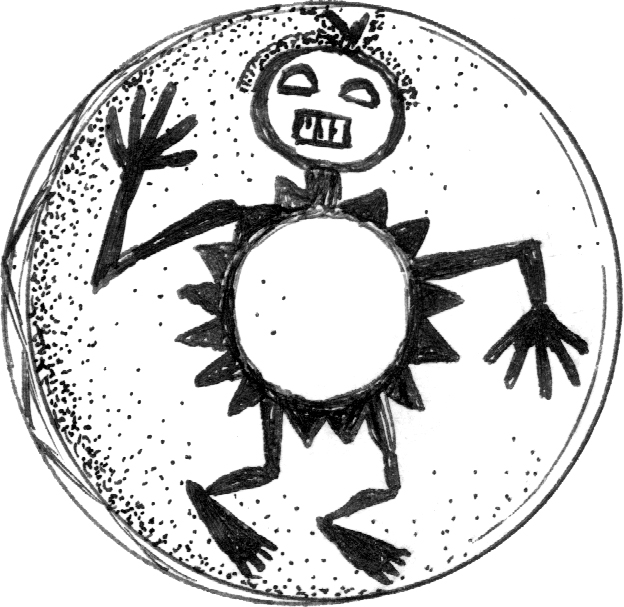

Boulders carved with clan symbols rest in front of each pithouse, telling the visitor immediately that this house is Snake, Sun, Bear, Coyote, Lizard, Eagle, Water, Parrot, Spider, or Bow clan. While the Canyon People are some of the least impressive humans on earth, I must admit that their rock painters and carvers are quite talented. The intricate details of the images are gorgeous.

By the time I reach the fire where my warriors stand speaking with the albino and Tocho, I’m trembling. I pull my rabbit-fur shawl tightly around my shoulders and wonder where Mother Mazanita vanished to.

Wasp Moth gives me a wary look. “You slept a long time, Blessed daughter. Are you well?”

“No, but I’m better. My pain is gone, which proves I do not have the plague. Where’s Mother Mazanita?”

“Told us she was going to live with her sister until we left.”

“Suits me fine. I can use another night’s rest without listening to her prattling on about witches seeping out of soul pots. What a despicable old woman.”

“I can use another day’s rest as well,” Tocho says with a sigh. “My knees—”

“I don’t care about your knees, you pathetic old man. They could fall off for all I care.”

Tocho’s deep wrinkles make him look a thousand summers old. Certainly too old to live much longer. Which will be a blessing. He’s as frail and useless as a shriveled-up old sheep carcass.

“May I dip you a cup of hot pinole?” Wasp Moth gestures to the pot, which contains a mixture of ground sunflower seeds and ground corn hanging from the tripod over the flames.

“What took you so long to offer?”

Wasp Moth kneels, pulls an ugly gray cup—clearly of local manufacture—from where it rests on the ground and dips it into the steaming pot. As he hands it to me he says, “It’s flavored with mint.”

I take the cup. “I know that. I can smell it from here. It must be ghastly strong. Have you been boiling it since dawn?”

Wasp Moth shrugs. “Can’t say. One of the old women carried it over and gave it to us for breakfast. Tastes all right to me.” Offhandedly, he gestures to the woman in the fringed cape who’s hurrying across the village, as though eager to put some distance between us and her. Probably spoke with Mother Mazanita.

“Well, it’s better than nothing, I suppose.”

Holding the cup in both hands, I lift it to my lips and take a drink. Actually, it’s delicious. I’ve never had pinole with mint. The disparate flavors complement each other.

I heave a sigh and look around. The cool air smells of damp earth from the morning storm. Along the bases of the rock outcrops, women use chert knives to gather alum for their dyes. The white chunks form beneath rocks after rainstorms. Alum helps set the dyes. The gatherers move from rock to rock, scraping the alum into pots, laughing as they work. Four large dye pots, ten paces away, rest in the central fire. Two women tend them.

I watch the younger of the women throw chunks of alum onto hot coals until they foam, then pour them into the dye pots. The colors in the four pots are vivid: Rabbitbrush makes the bright gold, while the mixture of greenthread and week-old urine produces the vivid red-orange. Sumac leaves and iron turn anything black. I am particularly fond of the rose shade made from dried prickly pear cactus fruit.

As I drink my pinole, my gaze drifts over the ten low humps of pithouses, past the racing children with dogs yapping at their heels, and down to the spring where the yellow leaves of cottonwoods waver in the light breeze. A doe and two spotted fawns leap through the shadows. Their movements are elegant, poetry in motion. Easy to kill. Why isn’t someone down there shooting them full of arrows?

“So, albino,” I say as I turn to look at him. “Where’s the old bag?”

He lowers his hand to his waist and pats the lump beneath his blue cape. “Here.”

“You can wear it on your belt, but I can’t?”

His eyes narrow, as though I’m truly too stupid to live. At length he responds. “Clearly.”

“And what about you, holy man?” I turn to Tocho. “Why didn’t you do something when it was trying to choke me to death?”

Tocho takes a moment to shove his hair behind his ears. “Did you actually feel hands around your throat?”

“Well, no. But she definitely paralyzed me. I felt like a beetle stung by one of those repulsive wasps with the red and yellow stripes. I knew I was going to suffer the same fate as the beetle and be turned into a mindless slave.”

The warriors go silent and swivel their heads toward me.

The albino glances at Tocho and softly says, “She’s not strong enough to be the Keeper.”

“Not while she’s ill, but later, perhaps.” As though curious about something, Tocho tilts his head, and asks me, “Did she speak to you?”

“You mean when she was trying to kill me? I heard nothing coming from the bag.”

I have no intention of telling him about the eleven dancing figures. They scared me badly. I’m fairly certain it was just that I was fevered, but …

“Her soul pot was resting right beneath your ear, and you heard nothing? Not even whispers?”

I shake my head. The fact seems to fascinate him. “No. Not a sound. Why?”

“It’s curious, that’s all. She ordered me to give you the bundle, but she hasn’t said a word to you. It’s as though…”

When he hesitates, I prod, “As though what?”

“Well, I don’t know, of course, but I wonder if perhaps I misunderstood her. Maybe you are not supposed to be the new Keeper. Maybe she just wants you to carry her pot.”

“I’m a pack dog for a disembodied witch? For what purpose?”

Tocho shrugs. “Impossible for me to say. Bundles can be very secretive.” He turns to the albino. “Do you have an opinion, Maicoh?”

The albino slips one hand inside his cape and pulls it back to expose the faded old bag tied to his belt. Barely audible, he asks the bag, “Is she the new Keeper?”

Both Tocho and the albino cock their heads at the same time, as though listening to the old witch’s response. To my left, my warriors mutter darkly. Do they hear the same voice?

I glare at Wasp Moth. “Do you hear it talking?”

Wasp Moth shakes his head. “Not from way over here.”

“What about you two?”

Iron Dog and Weevil shake their heads, but Weevil’s eyes go so wide, he could be a goggle-eyed old bobcat. His broken yellow teeth are visible in his gaping jaws.

“Are you lying to me, Weevil? Tell me what she said.”

“I heard nothing! I swear it, Blessed—”

“Perhaps I can help.” Tocho walks closer. “She said to tell you that the signal stations between here and Flowing Waters Town have been repaired.”

Wasp Moth frowns. “If that’s true, we should send a message to tell your father that we are only a few days away.”

“Where’s the closest signal station?”

“About a half day’s march to the south, Blessed daughter. We can make it by noon tomorrow, if you’re feeling up to it.”

“And if I’m not, you can rig a litter and carry me.”

Wasp Moth bows. “Of course we can.”

Tocho gazes down at me with tired, yet kind, eyes, and I have the sense that the old witch’s message was not simply about signal stations.

“Did she say something else?”

Tocho shakes his head. “Nothing you want to know.”

“I do want to know, old man.”

At the edge of my vision, I see the albino’s eyes narrow as his expression turns to stone. He doesn’t like it when I give Tocho orders. I should do it more often.

Tocho’s voice is tender, as though attempting to soften the blow, when he replies, “The Blessed Nightshade told me that her body is changing, lengthening into a wolf’s lean form, while her feet shift to paws. She says she is almost ready to lope across the face of the world.”

A chill runs through me. “In the pot? She’s changing into a wolf inside the pot? That’s not possible.”

The sound of Weevil’s panting is so distracting I whirl to glower at him. “Get out of here! You and Iron Dog, go down to the spring and collect some willow switches for me. I’ll boil them tonight to make powder for my headache.”

“Yes, Blessed daughter.”

Weevil and Iron Dog trot away toward the cottonwoods that surround the spring, but Weevil keeps casting glances over his shoulder, as though he expects something horrific to happen before he can get far enough away to save himself.

Grimacing, I turn back to Tocho, and repeat, “That’s not possible, is it?”

“I would have said the same thing.” He nods. “Living witches shift shapes at will, but I’ve never heard of a dead witch doing it.”

Maicoh’s hushed voice seems to ring from the cliffs. “This is Nightshade we’re talking about. I suspect she can do anything she wishes.”

The albino suddenly looks down at the bag hanging from his belt. As Father Sun sinks toward the western horizon, the blue wolf’s image grows sharper, clearer. I can see glittering white fangs now.