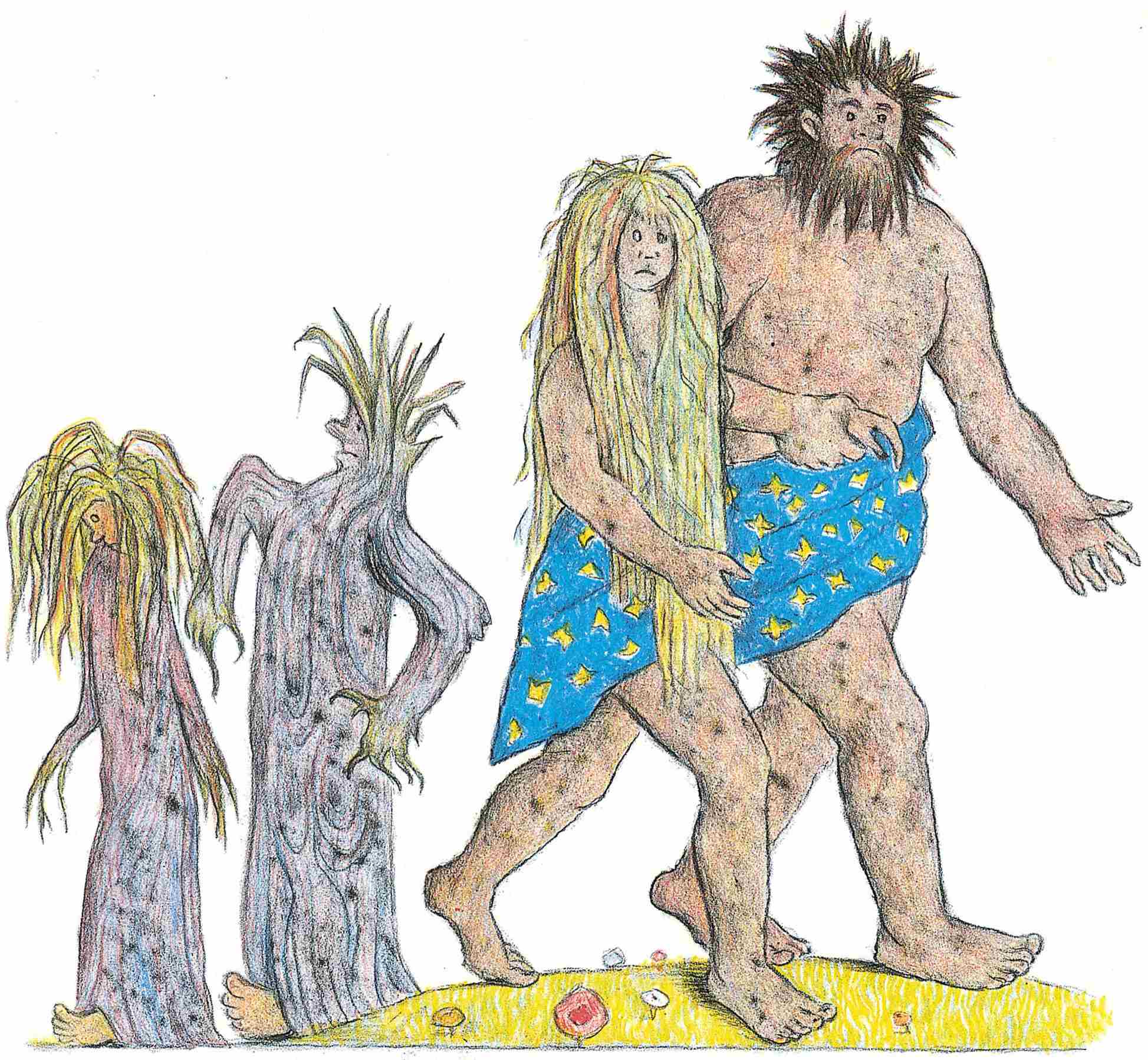

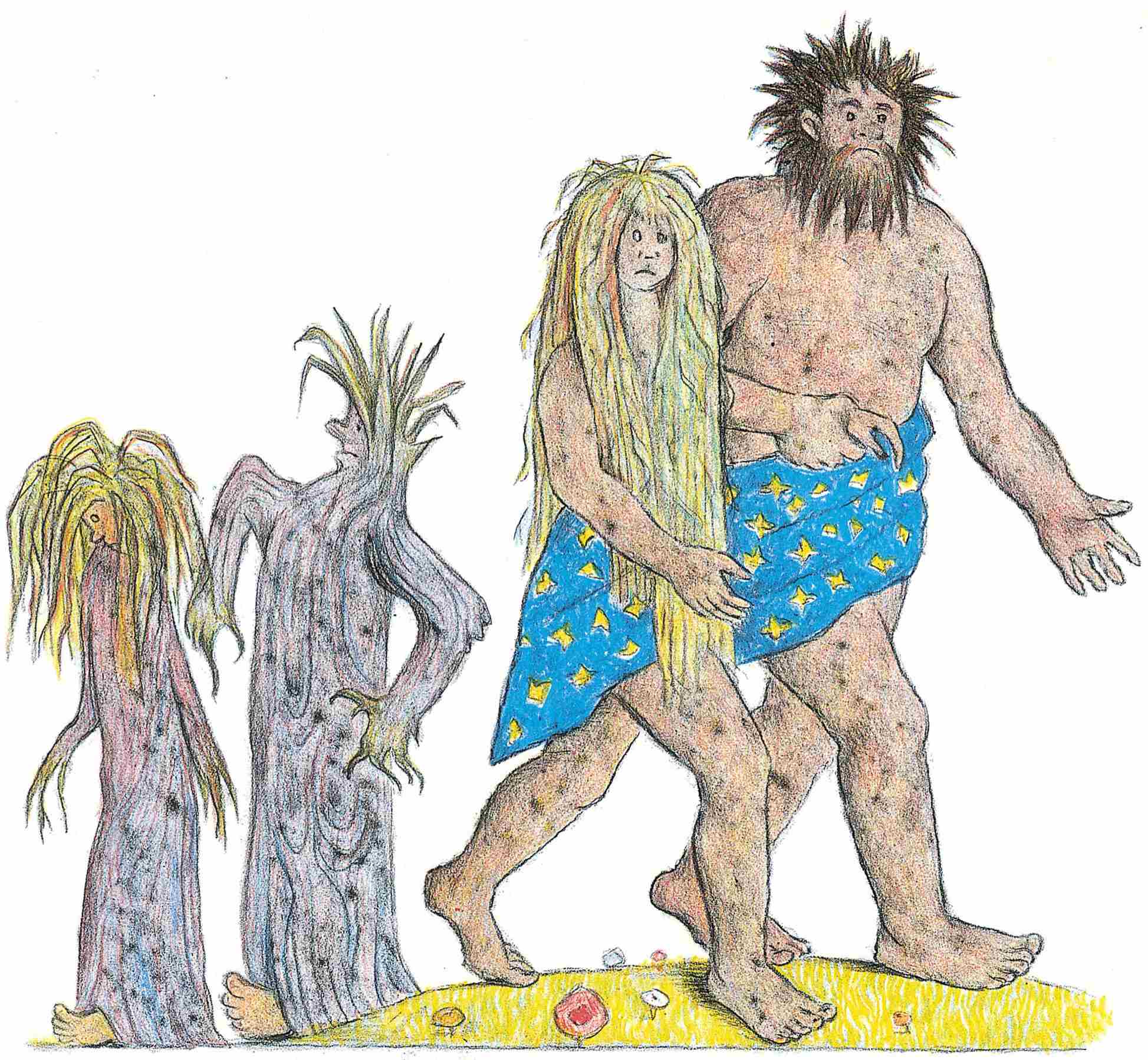

ONE DAY, as the three young Aesir walked along the seashore, their eyes fell upon two little trees, an ash and an alder, standing side by side. In these two trees they saw the makings of mankind—straight as gods and tough as wood.

But the ash and the alder were only trees; they had no souls, they could neither think nor move, and the sap that flowed beneath their bark was cold. So together the three gods blew life into the trees. Odin gave them souls, Hoenir gave them the will to think and move, and Lodur gave them feeling and warm red blood. Slowly the ash and the alder turned and twisted into a man and a woman.

Still, a naked, nameless man is not far above an animal, and the Aesir wanted human beings to be the greatest of all their creations. So they gave them names and loaned them their own cloaks until they could learn to make clothes for themselves. They named the man Ask (Ash) and the woman Embla (Alder) after the trees from which they had been created.

As a birth gift they gave them the whole earth for their home, and, to protect them against the onslaughts of the wild jotuns in Jotunheim, they made a fence of Ymir’s eyebrows and placed it around the earth.

Then the three gods made a home for themselves high up above the tallest mountains and set up a shimmering rainbow as a bridge between earth and Asgard, their home.

From Asgard they watched over Ask and Embla and all their children.

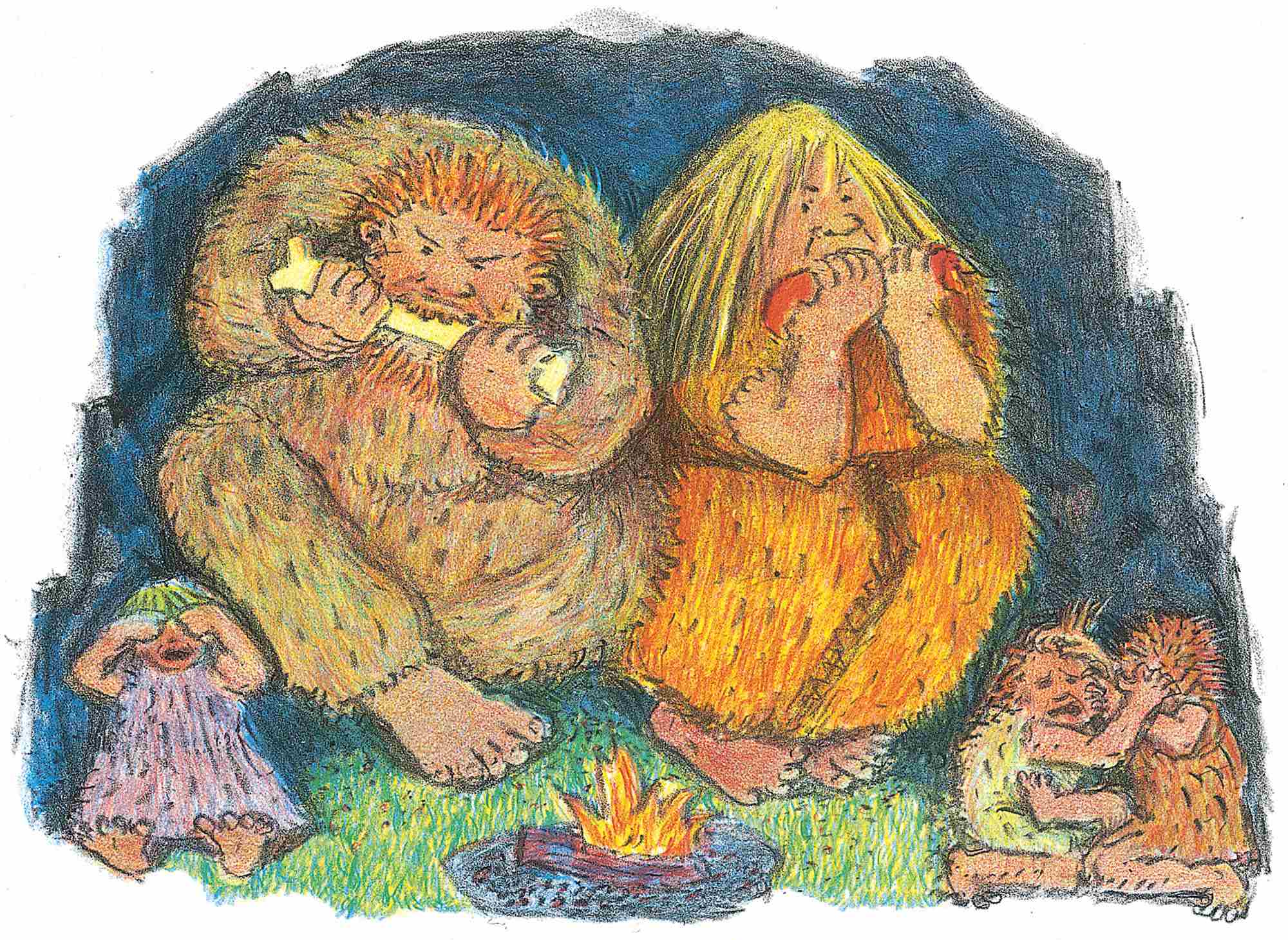

The first descendants of Ask and Embla were not handsome. Their skin was rough like bark, their joints gnarled. They ate wild plants, hunted animals with clubs, and wrapped themselves in furs to keep out the cold. They lived in hovels, had no manners at all, and their eyes were downcast and dull.

Their grandchildren were better in every way. They tilled the soil, lived in houses, sailed the seas. They ate well-baked breads and dressed in shapely clothes, and their shoulders were broad, their cheeks rosy, and their eyes lively.

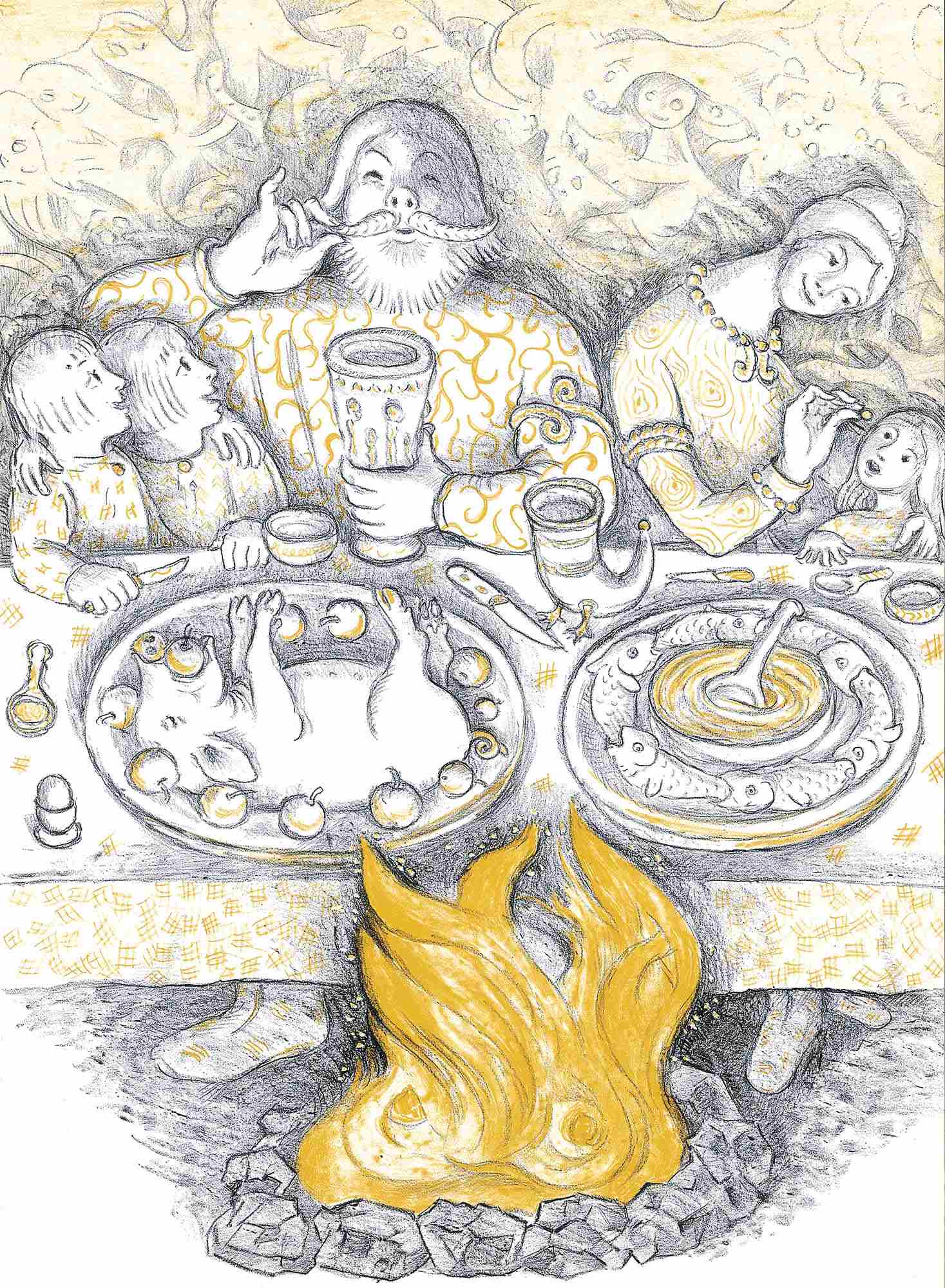

Their great-grandchildren were finer still. They were fair and handsome and sat at leisure in great halls, dressed in fine woolens and snow-white linens. They ate roasts from silver platters and sipped sweet mead from crystal goblets and ornate drinking horns.

They had manners, for Odin himself told them how to behave.

In the disguise of a wise old wanderer he often walked among men. A wide-brimmed hat shaded his face; a dark blue cloak, set with sparkling stars, hid his huge chest. He walked about the earth, testing the hospitality of people, for hospitality was very important to men who lived far apart in wild and roadless lands.

When he was welcomed to hall or hovel he seated himself by the fire and talked to the people.

“Your friend’s friends shall be your friends; your friend’s foes shall be your foes. Tread down the path to your friend’s house and don’t let it grow over with weeds,” he said.

“Always keep your door open to the tired traveler. The man who comes to your house with shivering knees needs a place by the fire and dry clothes and warm food.

“When you enter the house of a stranger, look into cupboards and dark corners to see if a foe might be hiding. Then take the seat that is offered you, and listen more than you speak. For then no one will notice how little you know.

“Always have a bite to eat before going to a feast; a hungry man is not a bright speaker.

“It’s an unwise man who sits awake worrying all night. When morning comes he will be too tired to think and matters will be still more tangled.”

And last, he always said, “Men die, cattle die, you yourself must die one day. There is only one thing that will not die—the name, good or bad, that you have made for yourself.”

Thus Odin, the Aesir god, sat by the hearths and spoke, and the people listened. When he disappeared, they knew they had been listening to the voice of the High One, and they held his words sacred.

The human beings were thankful to the gods for having created them and for sending sunshine and rain to their fields, and they sacrificed to them and worshiped them in sacred groves and sanctuaries. The Aesir, in turn, were fond of mankind and watched over them and protected them against the jotuns.

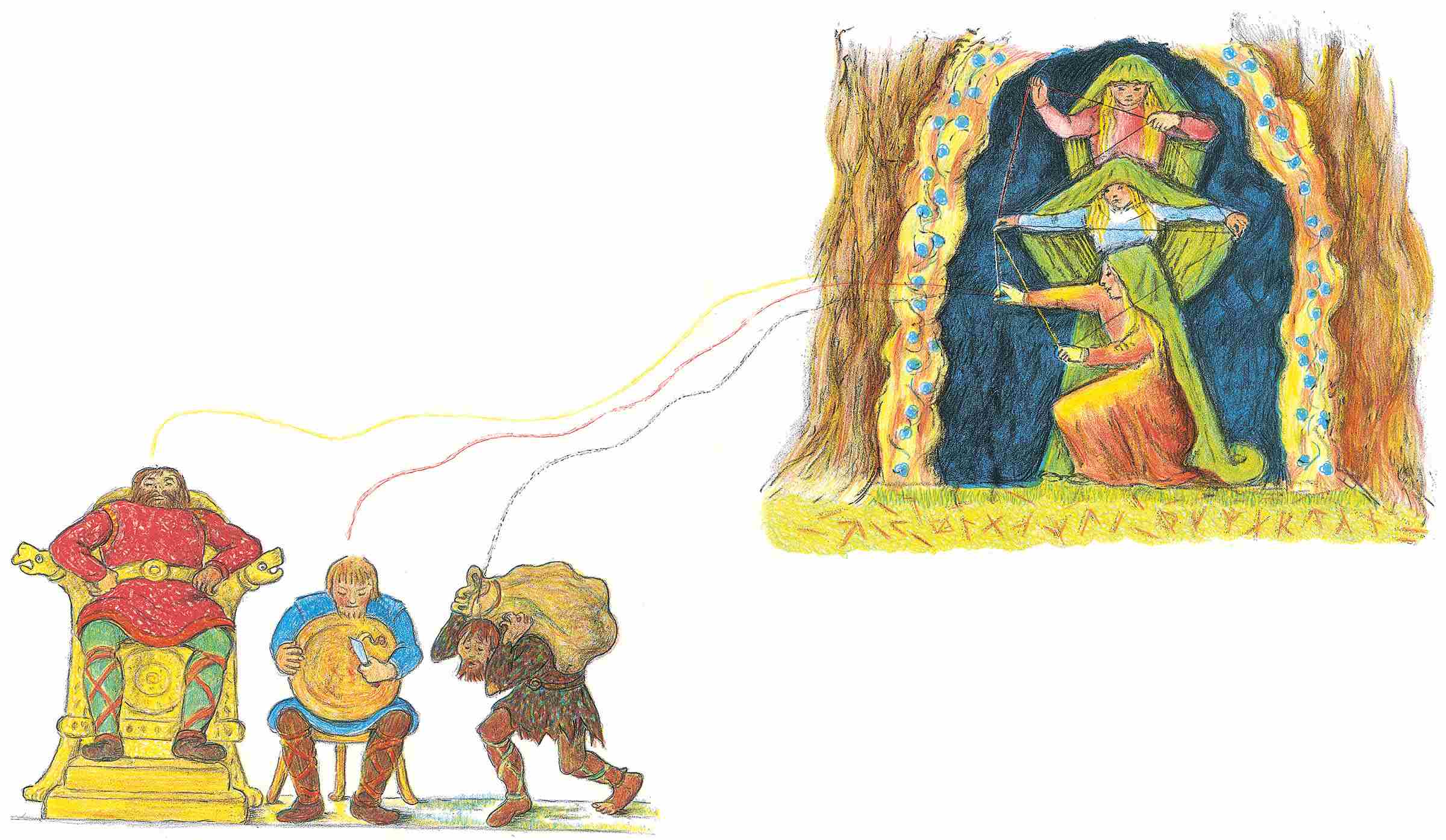

But it was the three Fays of Destiny, the Norns, who decided the fate of every human being. Their names were Urd, Verdande, and Skuld, and they knew what was, what had been, and what was to be. To every newborn child they willed a life of luck or a life of misery, a short life or a long one, for the Norns spun a thread of life for every human being. Mostly it was a gray, coarse thread. But for farmers and freemen they sometimes spun a finer thread in a brighter color. And once in a while, for a hero or a great prince, they would spin a thread of gleaming gold.

Nobody knew where the Norns had come from, or whether they were fairies or of the jotun race. But even the Aesir had to bow to the will of Urd, Verdande, and Skuld, for the Aesir were not immortal gods. They too must die when the Norns decreed it, like everybody and everything else.