WHEN the matter of the hostages had been settled, the Aesir and the Vanir sealed their pact of peace in a strange way. They gathered around a huge vat, chewed certain berries, and solemnly spat the juices into the vat. These divine juices took shape, and out of the vat rose Kvasir, the spirit of knowledge. There was no question that he could not answer, and no matter how much he was pumped for information, he never ran dry. On the contrary, his knowledge increased.

But one day, two gnomes drowned Kvasir in the essence of his own knowledge. Then they ran off with the essence to their home deep underground. There they poured it into three kettles, added honey, and sprinkled it with magic herbs. They brewed a mead so potent that whoever drank of it felt his spirit soar high and free, and ringing verse poured from his lips.

The mead made the gnomes feel so grand that they recklessly killed an old jotun, and when his wife came looking for him, they slew her too. But Suttung, the son of the old jotun couple, found out about it and came to avenge his parents. The gnomes could save their lives only by giving him the magic mead. Suttung hid the three kettles in a chamber deep in a mountain and set his daughter Gunnlod to watch over them.

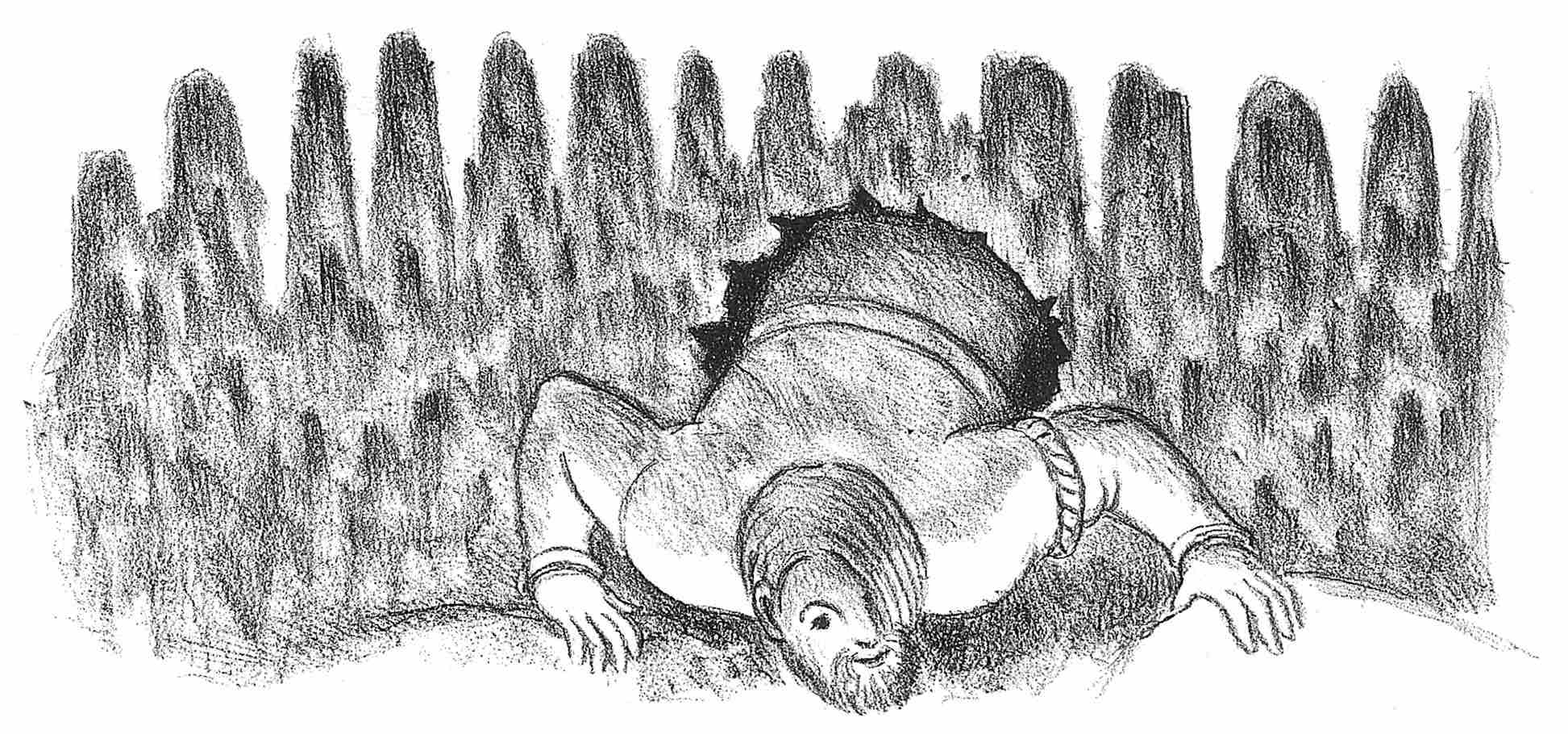

From his throne, the Lidslkjalf, Odin saw the jotun hide the three kettles and he decided that he must have the mead. So he changed himself into a snake and wormed his way into the mountain through a crack in the rock. When he came to the chamber where Gunnlod sat watching the mead, he took on the shape of a handsome young man.

“How sweet, how beautiful you are, sitting here deep in the mountain by your lonely self,” he said. And indeed it was true. Gunnlod was one of the beautiful jotun maidens, and in her loneliness she liked hearing about it. So she smiled and enjoyed the company of her handsome young guest. After three days she had grown so fond of him that she said he might have a sip from each of the three precious kettles she was guarding—one sip from each.

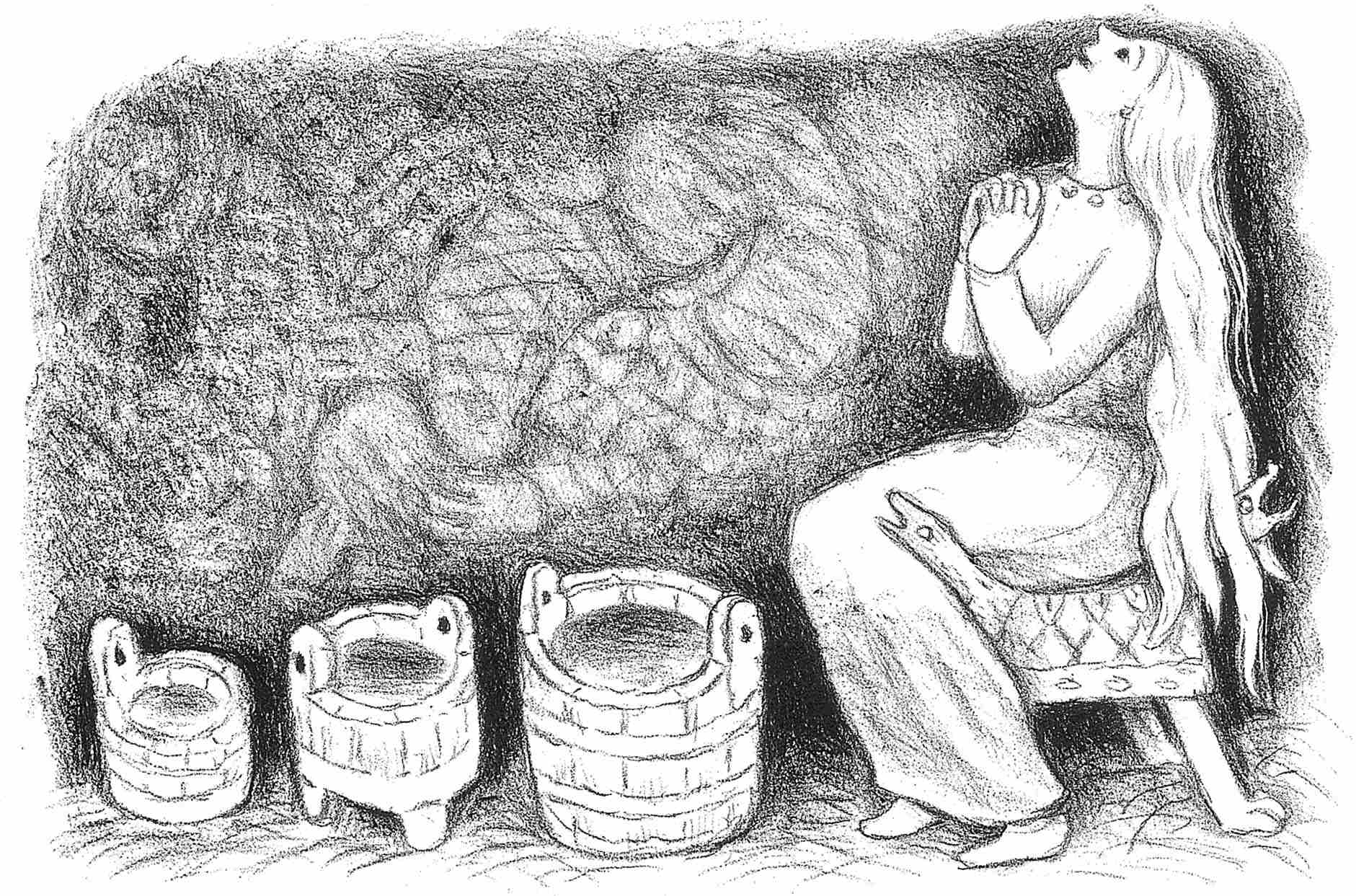

In three mighty gulps Odin emptied all three of the kettles; then he rapidly changed himself into an eagle and flew off. Poor Gunnlod sat weeping beside her empty kettles.

But Suttung, her father, saw the eagle fly away from the mountain, and right away he became suspicious. He also took on the shape of an eagle and set off in pursuit. And as Odin had three great kettlefuls of mead inside him, Suttung could fly faster.

Heimdall spied the two birds approaching Asgard and saw that the distance between them was becoming smaller and smaller. He knew what Odin had gone for, and he called to the other Aesir and told them to hurry and set all their pots and kettles out into the courtyard. Odin just barely had time to spit the mead into the vessels and fly to safety, so close upon his heels was Suttung. Thus Suttung had to return without his mead, and Odin kept it for himself.

After that Odin always spoke in stately verse. He let the other Aesir taste the magic brew, and he gave some to truly gifted men on earth. They became great poets, a joy to gods and men.

Odin had also lost some drops outside the wall of Asgard, and these dripped down to the earth, free for any fool to gather. But the drops had lost their magic power, and those who gathered them could write nothing but doggerel.

In this roundabout way poetry came into the world, to lift the hearts of Aesir and men. But Odin felt it always weighing on him that, to gain the gift of poetry, he had betrayed Gunnlod, a trusting maiden, and had left her alone to weep over her empty kettles.

To make up for it, Odin brought Gunnlod’s son, Bragi, to Asgard. He recognized Bragi as his son, taught him the power of the runes, and gave him some of Suttung’s mead to drink.

Thus Bragi became the god of the bards. And as a bard needs youth to sing, Odin gave him for his wife ldunn, the keeper of the apples of youth. Whoever took a bite from her apples did not grow old, and the Aesir depended upon ldunn and her apples to stay young.

With ldunn tenderly caring for him, Bragi always had sparkling eyes and rosy cheeks, although his face was framed by the long white beard of a sage.