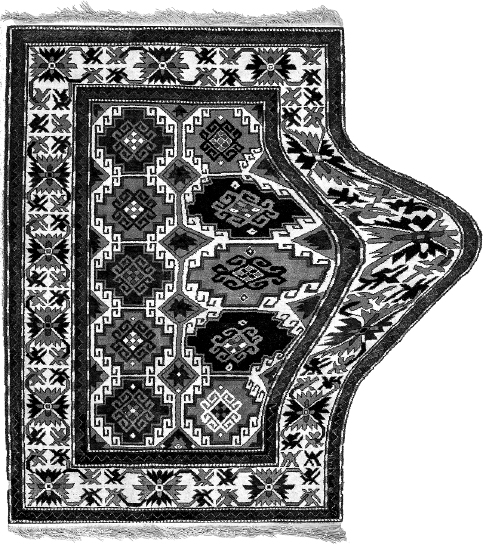

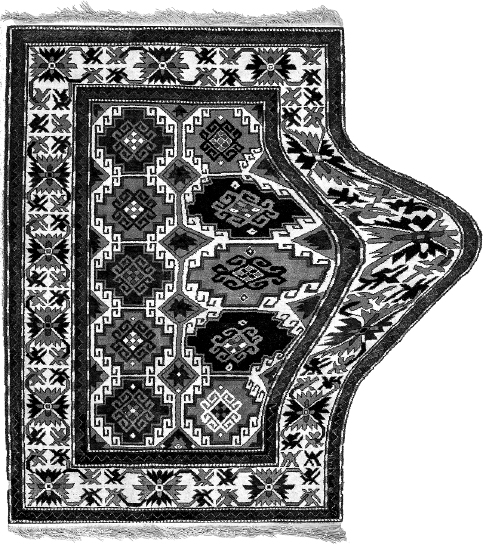

Figure 4.1 Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed creates traditionally woven carpets that resemble digital distortions. Faig Ahmed, Expansion (2011). Handmade woolen carpet, 100 × 150 cm. Image courtesy of Faig Ahmed Studio.

This book has been, in part, an exercise in speculative history. By “speculative history” I do not mean the kind of counterfactual historical fiction that asks what would have happened if the Nazis had won World War II.1 Rather, I mean the sense suggested by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, who, in their 2013 book Speculative Everything, argue that design should open the imagination, not constrain it; that being able to imagine—or even prototype—the future is crucial to thinking about the needs of the present. In proposing the metaphor of parallax as a means of investigating the historical evolution of data and images, I invite readers to speculate on the material consequences of a hypothetical framework that stretches from the early nineteenth century to the present. I do not suppose that applying any of my various “modes” of relating data to images consciously motivated the creator of any particular artwork or technology. But the process of taxonomizing these various strategies has helped pull several otherwise abstract tendencies, movements, and relationships into focus.

Moments of transition make for illuminating and contested histories. I hope it is no longer necessary to note that even the most rigorously researched accounts of the past are partial and idiosyncratic—and inevitably driven by the needs of their moment. Speculative history aspires not to comprehensive analysis, nor even narrative coherence, but to kernels of insight and unexpected connections that, at their best, extend beyond the immediate objects of study. The transition we are currently witnessing regarding data and images both draws attention to the forces of history and clouds our ability to perceive them. In particular, the cultural and industrial consensus around models of synthesis and convergence make it tempting to see this consensual vision as an inevitability. The parallax model was conceived specifically to complicate prevailing assumptions about technology and media. I hope that analyzing an eclectic range of examples—from the obscurity of experimental films and software art to the industrial strategies of media and technology giants—has demonstrated the value of looking closely at all of this.

Jonathan Crary once argued, “We will never really know what the stereoscope looked like to a 19th century viewer.”2 In part, this is because of the burden of historical certainty about “the way things turned out,” but also because of the impossibility of fully reconstructing the subjectivity of nineteenth-century viewers. This book goes a step further to ask whether we really know what today’s technologies of vision look like to viewers—us—in our own present. The strategy of defamiliarization, borrowed from Russian formalist literary theory, advocates viewing even the newest technology as if it were an artifact of the past, its users—us—as the product of our own material and social circumstances. This is easy if we imagine old technologies to be primitive and their users naïve, but this perspective is more difficult to sustain while being dazzled by our own innovations of the day.

In this book I deploy strategies of close reading and associative digression to analyze the shifting roles of digital media in articulations of space, visualization, and surveillance. I have also attempted to engage the tortured relationships between critical models devised to address visual, digital, and media cultures of the past quarter century. My goal has not been to reconcile these models—nor the generations of thinkers who deploy them—but to find points of intersection and resonance. I remain convinced that there is room for coexistence and benefit to be had from the cross-pollination of theories of pre- and postdigital visual culture.

The broader context for this investigation is about transience. The relation between data and images exists in a particularly rapid state of flux, but this is true for many domains. Transience offers an antidote to passive models of evolution and, worse, narratives of progress. I am also driven by other forms of transience, which in recent years have come to seem more urgent than ever. This includes the fragility and inequity of individual human lives as well as the fragility of our planet. In time, the Earth will be no more inherited by the wealthiest elites than by the meekest of the poor. The course we have charted during the last 150 years—roughly the same period of technological development this book is concerned with—shows few signs of reversing direction before we plunge headlong into a smorgasbord of dystopian science-fiction narratives in which our children will be cast, at best, as scrappy survivors.

That said, I have engaged only glancingly the environmental consequences wrought by the technology and entertainment industries responsible for most of my objects of study. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to foregrounding the physical substrates and environmental consequences of being digital. The ideology of “virtuality,” Jennifer Gabrys argues, “can even enable more extensive consumption and wasting.” She sums up this contradiction: “When electronic devices shrink to the scale of paper-thin and handheld devices, they appear to be lightweight and free of material resources. But this sense of immateriality also enables the proliferation of waste, from the processes of manufacture to the development of disposable and transient devices in excess.”3 Gabrys cites Walter Benjamin’s analysis of the “fossilized” nineteenth-century arcades as evidence of technocultural practices—a collection of obsolete, irrelevant, and ill-advised artifacts—that offer useful insights into times past and the mindsets of those immersed in their own era’s frenzy of the technological.4

Jonathan Sterne has likewise put forward an unforgiving analysis of the material consequences of digital consumption. In an essay titled “Out with the Trash,” Sterne writes, “Obsolescence is a nice word for disposability and waste.”5 For Sterne, the very definition of “new” media is predicated on the obsolescence—the literal burying—of the old. “The entire edifice of new communication technology is a giant trash heap waiting to happen, a monument to the hubris of computing and the peculiar shape of digital capitalism.”6 And in The Stack, Benjamin Bratton advocates attending to physical as well as virtual infrastructure when critiquing the digital. “Computation is not virtual; it is a deeply physical event, and The Stack has an enormous appetite for molecules of interest and distributing them into our pockets, our laps, and our landfills.”7 In this context, the concerns of this book related to the physicality of digital imaging and its reciprocal computationality of vision represent only a subgenre of these larger environmental issues.

Lastly, Sean Cubitt’s Finite Media offers a sustained and erudite meditation on the imbrication of digital materialities and environmental consequences. The book is overtly dedicated to examining the “deep dependence of contemporary media on energy and materials.” In our relentless development of technologies for communicating among ourselves, Cubitt argues, “we also inadvertently communicate our dismissive relation to the humans and natural environments who pay the terrible price for its efficiency, even for its poetry.”8 Cubitt further asserts that any hope of change lies in the social—not the technological—domain, noting that “it is essential to turn our gaze toward the polity—the assembly of human beings in action—as the site from which might arise any alternative. … It is we ourselves who must become other in order to produce an other world.”9 The point to be taken from all this is the falseness of the once-prevalent material/immaterial binary. The digital has always been physical.

Recent years have brought an implicit reinscription of the physical/digital divide in the form of the “New Aesthetic.” So-named by designer James Bridle, the New Aesthetic denotes a cluster of art practices that emerged in the 2010s seeking to manifest the unique attributes of digital imaging—especially pixelated 8-bit graphics—in the physical world. Describing this as a practice of “seeing like digital devices,”10 Bridle valorized work by international artists, including Canadian novelist Douglas Coupland, whose life-sized Pixellated Orca (2009) sculpture is installed outside the Vancouver Convention Center; Dutch artist Helmut Smits, who dubbed a one-meter-square patch of dirt Dead Pixel in Google Earth (2008–2010); and Azerbaijani artist and rug maker Faig Ahmed, who creates traditionally woven carpets that evince distinctly digital distortion effects. These works are indeed seductive, and we may appreciate their perversity and idiosyncrasy as individual works, but as a movement, the New Aesthetic remains burdened by the combination of formalism and ahistoricism inherent in its name. Like firstness, few claims of newness are ever really justified.

Figure 4.1 Azerbaijani artist Faig Ahmed creates traditionally woven carpets that resemble digital distortions. Faig Ahmed, Expansion (2011). Handmade woolen carpet, 100 × 150 cm. Image courtesy of Faig Ahmed Studio.

To more productively theorize the impulse behind the New Aesthetic, several writers turned to the concept of “eversion.”11 Science-fiction author William Gibson coined the term in a New York Times op-ed piece in 2010 to signify the process by which cyberspace (another Gibson term) erupts from the virtual into the physical world. Gibson’s op-ed came in response to the announcement that Google was moving from the ethers of the internet into brick-and-mortar corporate personhood. He wrote, “Now cyberspace has everted. Turned itself inside out. Colonized the physical. Making Google a central and evolving structural unit not only of the architecture of cyberspace, but of the world.”12 Echoing Gibson, Bruce Sterling dismissively noted that the New Aesthetic’s eruption of the digital into the physical should have come as no surprise. “It’s been going on for a generation. It should be much better acculturated than it is.”13 I do not always agree with Sterling’s forays from the domain of science-fiction into cultural criticism, but despite his chastising tone, his point resonates with a core argument of this book. What is at stake in nearly all the media I have curated for this project is their integration in a long-term two-way process of acculturation. Whether media artifacts intend to do so or not, they teach us how to understand the technologies that make them possible.

In addition to the materiality of the digital, an underlying concern of this book has been the role of technology in producing neoliberal subjects ready to accept their role in the marketization of everyday life. A great many more factors are at play in this dynamic, of course, and I don’t imagine that this book’s warnings—however earnestly they might be issued—have much to offer in the absence of a related social movement. Given the imbrication of digital networks with the ideologies of neoliberalism, developing a sophisticated understanding of the functioning of digital systems may ultimately increase our agency in both domains. It is not only technologies whose secrets must be revealed, but the structure of the multiple social and political systems in which they are embedded. A thoroughly expanded view of the “war between data and images” would also take account of the many other wars, both literal and metaphorical, that we are now—or soon will be—engaged in.

What we choose to pay attention to when we create or study “digital culture” is an ethical matter, and the questions we don’t ask are as important as the ones we do. So, why is it important to focus on data and images at this moment? Data can be used, as photographs once were, to awaken consciousness to systemic injustice and the need for social change. Where images are still frequently tied to the subjective position of an individual or the camera, understanding data necessitates thinking in terms of complex and interlocking systems. The message of this book is not meant to be pessimistic, even if my trust in the liberatory potentials of media and technology often wavers. I will say that the faith that even more technology can right the world’s wrongs could only flourish in a cultural unconscious that has been too long soaking in the warm bath of Hollywood endings. Ultimately, my hope is that greater agency will follow from better understanding how our perceptions of the world are shaped by technologies of vision, specifically the entangled realms of computation and mimesis. As my repeated preference for the negotiated mode suggests, I do not view the function of data and images as an either/or proposition; by considering both at once and in relation to the other, we gain the greatest insight. If images allow us to see where we have been, and data reveals certain contours of the present, perhaps through juxtaposition of the two, we can identify the places that are worth struggling to go next.