Tete Convoy in Mozambique

Notes from a diary, 16/18 February 1973

While Portugal fought its military campaigns in Africa, the town of Tete – a strategic African settlement dominated by a huge suspension bridge across the Zambezi River – came to represent one of the last of the embattled outposts of an Imperial tradition that had lasted half a millennium. When I visited the place in the early 1970s, what was going on in this vast land on the east coast of Africa was a chapter of recent history about to close.

I’d gone through Tete with Michael Knipe –the London Times man in Southern Africa at the time and we were to discover an archetypal Portuguese-style settlement that could be found in many parts of the southern half of the continent. Critical times these were, in what European pundits would term ‘Africa’s Liberation Wars’.

But for the great Zambezi, Tete could have been mistaken for Luso in Angola or Cacheu in Portuguese Guinea where the first of Prince Henry’s navigators made landfall on African soil for fresh water in their bid to discover a sea route to the spice islands of the East.

By the time we arrived, it was clear that the ongoing conflict in the adjoining region had been tough, especially for the hardscrabble black population where, apart from the military, opportunities to earn those few extra escudos were sparse. Almost all of the town’s Portuguese civilians had left a year or two before, in part, because normal commercial activity had ended. More likely they’d been intimidated by the war. More often than not, hostilities would start at the edge of town, almost as soon as the sun disappeared over the jungles to the west.

With all the soldiers and military vehicles about, there was no mistaking that armed rebellion was on Tete’s doorstep. Worse, nobody in uniform was prepared to say how this complex socio-military conundrum would end.

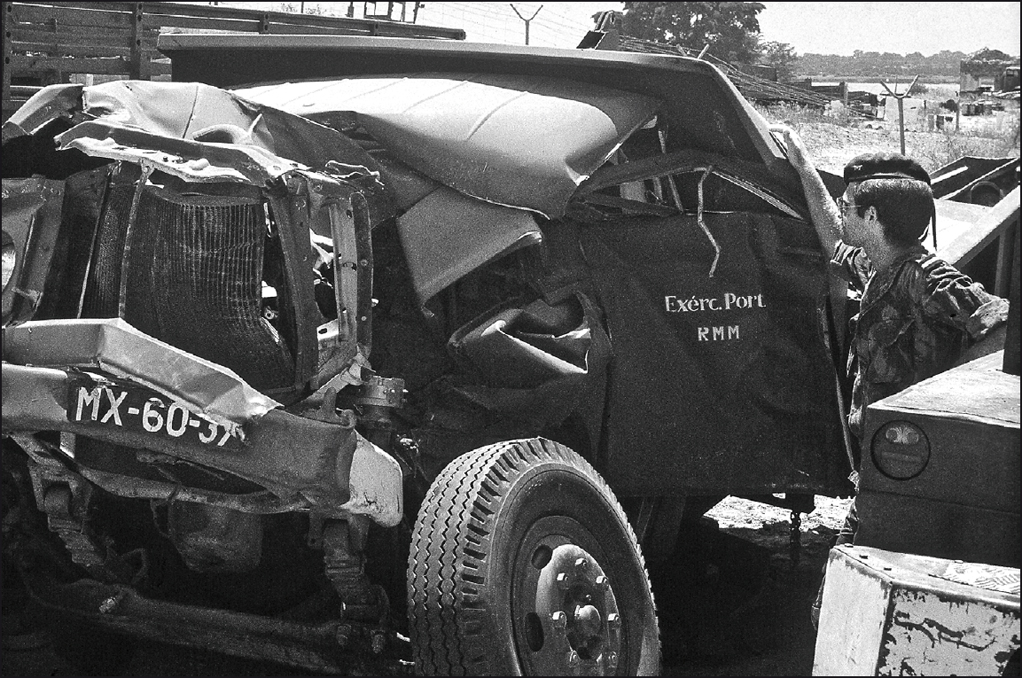

As hostilities gradually became more intense, mines began to take a bigger toll. There wasn’t a day that we didn’t spot vehicles towed in from the bush or hauled back to town on low-loaders after they’d been blown up or ambushed. Many more trucks were destroyed by landmines than in enemy ambushes, their cargoes either removed or, when oversized – like mining equipment or industrial plant – abandoned, hopefully to be recovered another day. The rebels would see to it that it rarely was.

Such was the nature of insurgency in this remote corner of tropical Africa that fringed the Indian Ocean, a very different kind of war compared to what was going on just then in South East Asia.

Moving through Mozambique in the late 1960s and early 1970s was always an experience. The region was remote and because of the isolation, there were few independent observers either willing or able to chance their luck in an unforgiving corner of Africa. Communications were invariably a consideration, especially in the interior: most times they simply did not exist. There were phones, but they didn’t always work. Faxes and cell phones were not yet on the market. You considered yourself lucky to get a call through to Europe or America once you’d left the comfort of Mozambique’s big cities of Beira or Lourenco Marques, though a fat bribe helped if you were prepared to use military equipment.

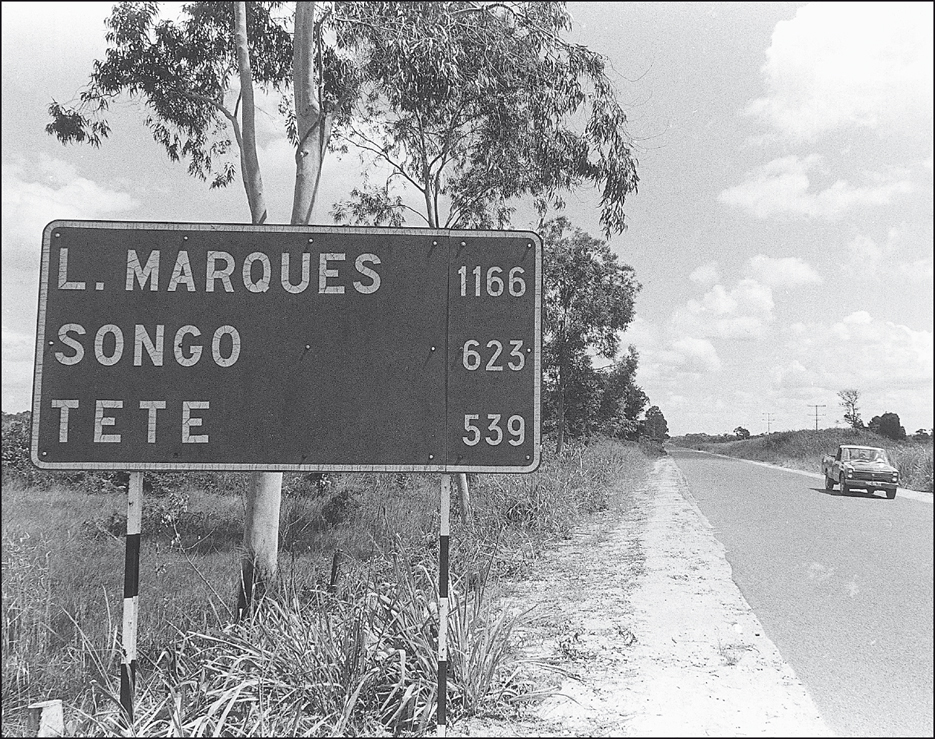

In the riverside town of Tete – it lies on the south side of the great Zambezi – just about everything began with the bridge, which led to the Tete Corridor the road north to Malawi. Landmines were a serious problem for us all. (Author’s photo)

Getting about was always problematic. You either travelled in convoy or you didn’t go anywhere. Between towns of the central regions and the north, that was something that happened perhaps twice a week. Even then, if the guerrillas had been active, delays were commonplace, sometimes as long as a week. Much depended on the competence of local garrison commanders.

Compared to Vietnam, the number of combatants deployed by the Portuguese Armed Forces in Mozambique was modest. Equipment fielded by both sides in this harsh unforgiving African hinterland was not nearly as sophisticated as that deployed in South East Asia by the Americans, or for that matter, by the French before them. In all of Mozambique – a country almost twice the size of California, and curiously, roughly the same elongated shape – there were only a fraction of the number of combat helicopters you were likely to find in a single Vietnamese city like Da Nang or Hue while that war raged.

For the isolated scribe covering the African beat, the crunch centred on the fact that Vietnam was where things happened: South East Asia was constantly in the news. Then as now, sadly, Africa had already been relegated to backwater status by most European and North American editors

A Portuguese Army Berliet heavy truck with troops onboard played the role of escort at the front and rear of our columns, with one or two troop carriers taking up positions in-between. (Author’s photo)

Our road to Tete, overland from South Africa, was circuitous. After crossing the Limpopo River, Knipe and I spent a week in Rhodesia – then also at war. The intention was that he would return to Johannesburg from Mozambique while I kept on heading north. I would travel the length of the Tete Panhandle – first to Malawi and on to Lusaka in Zambia (then another black African country technically at war with the ‘White South’) my final destination being Mobutu Sese Seko’s Zaire, or what had formerly been called the Congo.

But like others on the road, we had to wait for the next convoy and for three or four days, Tete became home. It was a distasteful sojourn in the town’s only hotel, the Zambezi, where the plumbing didn’t work and meals, such as they were, an unappetizing and often unsanitary grind where you competed as much to catch the eye of the one of a dozen waiters standing around as with the flies on your fork.

There was little to do in that heat that was both soporific and enervating and if you hadn’t packed a reasonable supply of books, you were left staring at the walls of your hotel room. Not that it mattered much because there was no air conditioning either. A film or two might have helped, but the only movie house had been shuttered and even if it hadn’t been, whatever might have been on offer would have been in Portuguese anyway, and without subtitles.

Most times when we did hit the town – always after dark when a light breeze came off the river – we were left to make our way past a succession of people who seemed to do little more than drink cheap wine, or thugs who would offer us a local girl for the price of a cocktail. The Portuguese military presence was everywhere, the majority in their wavy-coloured battledress who made the best of their off-hours in the torpid, dust-choked streets. Army trucks trailed endless little sandstorms in their wakes as they trundled through town and that didn’t help either.

Wrapped around a dirty crossroads on the banks of a the third biggest river on the African continent, Tete could easily have passed for a film set depicting the early years of the great American trek to the west. The only difference was an occasional, modern-looking building and a communications aerial on the tallest hill that overlooked the town. There was nothing to remind us that the settlement was one of the first inland trading posts established by Portuguese mariners who first sailed up this great waterway in their shallowhulled galliots in the 15th Century.

Much of what happened in Tete centred on the couple of thousand men of the 17th Battalion, as well as the three or four helicopters and ground support squadrons that made up the bulk of the town’s defences. Essentially, it was a captive market, for the troops had nowhere else to spend what little they earned.

The colonial gloss and glitter of Lourenço Marques – Maputo today – lay more than 1,000 kilometres to the south.

For those who took that extended overland leg southwards, there were still more military convoys for the first leg of the journey, at least until you reached Beira – Mozambique’s second city – as I was able to do on my way back home more than a month later.

There were big plans afoot for Tete, we were told in the first in-house briefing with Tete’s military commanders. One of the biggest hydro-electric dams in Africa was being built across a gorge on the Zambezi River, more than 200 kilometres upstream. That construction, we were assured, promised long-term dividends, but as we now know, it was only completed after the war ended. By then the majority of the Portuguese had decamped, bags and baggage, back to the metrópole.

At that stage, getting the dam finished on schedule had become a formidable task, especially since it was to be the biggest man-made body of water in Africa, second only to Egypt’s Aswan. For their part, the insurgents hurled everything they could muster at both Portuguese civilian and military interests in efforts to halt construction. Along the way, an awful lot of lives were lost.

Twice each day, starting at dawn, lurching open trucks that carried two platoons left Tete to guard the shipments of supplies, men and equipment headed towards the gorge. That was the easy part, because the road was tarred and the threat of mines were minimal. But that did not stop the ambushes, which seemed to keep an intermittent pace with the convoys and would take an almost inevitable daily toll.

The Moatize Junction was a compulsory stop while the road was ‘swept’ in both directions, for us heading north and for a southbound convoy heading our way. Moatize was then one of the country’s major sources of coal and has since become one of the biggest coal mines in Southern Africa. (Author’s photo)

Tete’s Barracks Square was where all military activities were coordinated by the military. Writing about the place, British writer James McManus recalled that it looked ‘absurdly Beau Geste’. From there too, patrols around town would set out before dawn each day and check routes leading in and out for booby traps and mines which, we were to discover, were sometimes responsible for the first casualties of the day.

Security in and around Tete was tight and strangers were invariably regarded with suspicion. We fell in the latter category and it came as no surprise that journalists like Knipe, James McManus and I, though tacitly accepted because we’d made the long haul north, were not made overly welcome. In any conflict, we were already aware, the Fourth Estate is routinely regarded with suspicion and the Portuguese military establishment was no exception.

In my case, I was fortunate because I’d previously covered the war in Angola. Also, I’d been given an informal letter of introduction to the local commander and that opened all the doors. Having experienced combat on the west coast, and then transferred my allegiance temporarily to Mozambique, it didn’t take long for me to be accepted as ‘one of them’. The trouble was that it invariably happened after the metal cap of the first bottle of aguardiente had landed in the bin.

In spite of the booze and bonhomie, talk about the guerrilla role in the conflict remained guarded, especially in the presence of us scribes. Reports of actions and casualties were a given, but there was never any serious talk about the adversary: it was almost as if the guerrillas didn’t exist. Casualty figures were always ‘secret’ and when there was an ‘incident’, such discussions in the officers’ mess were usually conducted in whispers.

The consequences of an ambush along that stretch of road a few weeks earlier. (Photo Revista da Armada)

The general approach to the war was different to what you’d find in other conflicts such as in the Congo, Algeria or neighbouring Rhodesia. One got the idea that many Portuguese officers liked to think – and some actually believed – that it was all a rather temporary affair, a bit of trouble with local savages that would soon be over, we were told often enough. The gesture was patronizing and that annoyed because we’d all done time at the sharp end and in this, Mozambique was very different from what I – and others – had already seen in Angola and Portuguese Guinea.

There, at least, the Portuguese Army didn’t ignore the threat. Rather, they got to grips with it.

The convoy left Tete at dawn. In a straggling line astern, the trucks rumbled across the river and were halted briefly at what passed for a tollgate at the far end of the bridge.

There were machine-gun emplacements at several points along the structure, some illuminated by a string of searchlights that continually swept across the water below.

One by one, the sleepy-eyed drivers paid the fee and moved the last 20 or 30 kilometres of metalled road to Moatize. There, under military supervision, we would assemble for the remainder of the trek to the Malawi border, almost 200 kilometres to the north.

Not all of Mozambique’s roads were mined. This stretch leading from Tete towards Beira was tarred and the occasional ambush was the only concern. (Author’s photo)

Some of the trucks in our column were bound for Blantyre, the capital of Malawi, a tiny country that straddled the north-western border with Mozambique. Others were headed further north, where they would again cross into Mozambique territory and where hostilities were at their most intense.

The majority of vehicles travelling with us were ten or 12-wheelers, including a number of low-loaders from Johannesburg factories that hauled freight bound for the Zambian Copperbelt. The drivers were a motley bunch, mostly professional haulers, some white, the majority African.

There were few among them who were indifferent to what lay ahead. Their guffaws and uneasy, conscious swaggering as they gathered in groups prior to us setting out were typical of travelling groups under strain. They’d all survive, they confidently told each other and they’d smile and nod their heads. What a way to earn a living, one of them chuckled.

There were many opinions about what lay ahead, as might have been expected in an area where there were landmines buried in the soft, gravel-topped laterite shoulders along the route and where Portuguese and insurgent forces had been making almost daily contact for almost a decade of war. The enemy was out there, waiting, the drivers would tell each other. Then the banter would start again: who would drive behind whom, which drivers were considered lucky or had experienced this kind of thing before and had come out unscathed. Anybody who had done six or eight trips across this narrow strip of no-man’s-land without being hurt automatically earned great respect from his colleagues; he was the man to watch, they’d say quietly among themselves.

Somebody pulled out a bottle of South African brandy and everybody took a swig. A few Portuguese soldiers nearby barely noticed, and if they did, they said nothing. There would be no policing on this stretch of road.

There were many views about what lay ahead. Quite a few of the drivers had been shot at or mortared and just about everybody knew somebody who’d been hurt. Not too many killed, it seemed.

‘One man he die last week…Mulatto…his truck he go…boom…very big mine!’

That came from a swarthy trucker from Madeira. His observation was lost on many because of his poor English and nobody made any comment. Most of the drivers continued doing what they’d been busy with or looked deep into their cups or tin mugs. Other drivers kept drinking, even though the sun had barely clipped the thorn and baobab trees clustered to the east beyond the railway station and coal dump at Moatize.

The man who spoke had a lot to say during the three-day convoy run. He’d done the trip often enough he told us, and made the point that he preferred to travel somewhere towards the rear of the column.

‘Better others hit the minas,’ he’d quietly comment, going colloquial when nobody else was listening. All we knew about him was that he was bound for a settlement in the interior which had been attacked often enough in the past. His cargo was his own business and he said so; that security thing again.

Apart from two buses packed with Africans on their way home from South African gold mines, there were about 35 trucks assembled at Moatize. Some were taking cargoes through to Zaire and sported Rhodesian plates. These would be replaced by Zambian tags for the final leg of the journey.

There were two private vehicles on the road with them, our Land Rover that had Dutch registration, as well as a medium-sized English car on its way to Zambia. The driver, a youngster from York was under contract on one of the copper mines and had returned from long leave in Britain with his vehicle. He’d been forced to head east and cross at Tete after waiting for six days at the Kasangula Ferry in Botswana; he said he’d rather risk landmines and ambushes six hundred miles to the east to taking his chances with President Kaunda’s undisciplined Zambian Army in an unstable hinterland where South African forces regularly intruded.

He’d made that choice after reports had come across the river of drunken soldiers having fired on another civilian car which had tried to cross southwards.

A woman travelling as a passenger had been wounded …

Portuguese bureaucracy and a tendentiously aggressive enemy eroded our schedules from the start. We were told the journey would take eight hours. It lasted three days. On that first morning, we were all left standing in the sapping heat of the Zambezi Valley for four hours before we eventually pulled out.

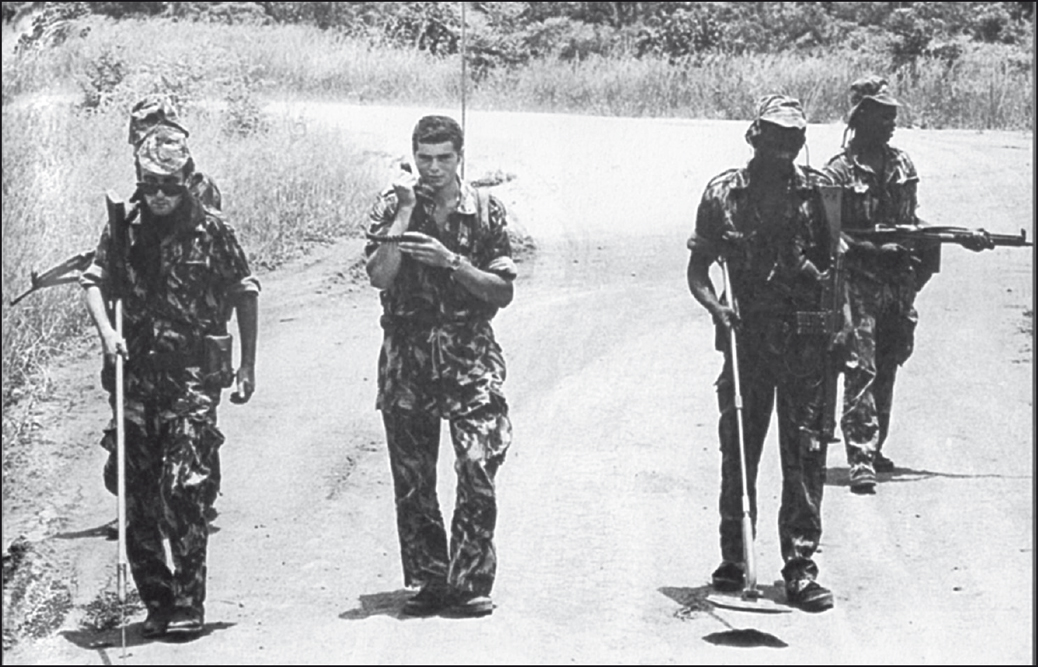

A squad of Portuguese Army sappers sweep the road for landmines. (Author’s photo)

An hour before leaving, a bunch of civilian officials – they were in khaki and displayed rank – approached the convoy. The bureaucracy that followed quickly became tiresome. Names were checked against lists, vehicles against registration plates, passports perused, cargoes vetted, instructions issued and questions asked. Weapons, tape recorders or radio equipment?

‘Anybody with binoculars?’ somebody queried. There was no reaction, even though one of the drivers sported a 400 mm tele-lens for his Nikon camera.

Finally the civilians were required to sign a document, in triplicate, which exonerated the Lisbon Government against claims in the event of any kind of military action. The final paragraph, in good English, indemnified Lisbon against losses that might be inflicted on us by the Portuguese army and air force.

We signed…anything to avoid delay.

At this stage Erico Chagas, a young Portuguese army lieutenant introduced himself. He’d been watching us from a distance and only then did we understand why. He needed to get to Munacama, he told us. He would travel with us, admitting that the Land Rover offered the most comfort. There was no question of him asking permission: it was already a fait accompli.

Young Chagas was to join his unit, about 30 minutes by road from Zobue, one of our destinations in the north. Born in the Mozambique capital and educated in South Africa, he spoke good English. We gathered that he’d been fighting for two years and, on the face of it, was clearly professional in his approach to all things military; the young man was tough and seasoned both by Africa and by conflict. As we were to discover later, Chagas liked to say that he’d seen and done it all.

Soviet anti-personnel mines such as this one were a constant worry for those of us in the convoy. They were often laid at random, right alongside the road at likely stopping points and casualties sometimes resulted. (Author’s collection)

We were happy to have him onboard: with a Portuguese Army lieutenant in our vehicle, we’d be spared further inspection.

The young officer was casual about most things, including the prospect of combat. It helped that he was as familiar with the bush as his native trackers. As to being ambushed while travelling in convoy, he was dismissive. Of course we’ll be ambushed, he declared impassively, ‘but the bastards never come very close…much of it is just noise’.

‘Mines, yes! But ambushes…ha!’

His comments were derisory, and sometimes contentious. The terroristas, as he called them, rarely caused any real damage, he said. ‘They don’t aim, so the shots are almost always high. And anyway, he suggested, it is old law. Unless someone is firing specifically at you, chances are that somebody else will be hit …’

He was explicit that we travel towards the rear of the column. He pointed at the truck belonging to the Maderian. ‘We stay behind him. He knows the tricks.’ The man from Maderia had already spaced himself well down the line. It was his contention, we learned, that the more wheels that passed over the track before us, the better. ‘Let others take chances,’ he reckoned.

More instructions were issued by our escorts, who had called us all together. Chagas translated.

We were to stay between 50 and 100 meters behind the next vehicle. If the truck ahead of you was hit, the explosion shouldn’t affect the truck immediately behind, though sometimes a front and not real wheel detonated a mine, which often enough caused casualties among those in the cab. The military spokesman stressed that each vehicle should follow exactly in the tracks directly ahead; as he said, slowly and distinctly ‘not to the right of it and not to the left, but on the tracks of those who have gone before.’

Because of the dust, this might sometimes be difficult, one of the other officers conceded.

Should one of the vehicles be blown up, it then became the responsibility of the troops escorting the column to search for more landmines, because they were rarely laid singly. And when that happened, he declared, nobody was to exit his vehicle and move about.

‘There are landmines for trucks,’ the officer declared, with Chagas keeping pace with a good translation, ‘and there are landmines for people. Consequently when the terrorists lay a bomb for a vehicle, they hope that some inquisitive person might get out and walk about to find out what was causing the hold-up’. That had happened often enough before and there had been casualties, he disclosed.

By now some of the Rhodesian drivers had edged closer to better hear Chagas’ translation: few had more than a basic understanding of the language.

The officer continued: ‘Remember all of you, and this is important. With landmines, all casualties are serious’. He added that it often meant calling for a helicopter to evacuate the victim…‘but there are times when there are no helicopters available…so the man can die.’

He told us that while there would be several officers travelling as passengers to re-join their units up-country, the convoy would be in charge of a sergeant, a wiry, intense little man whom he brought forward and introduced to the gathering.

‘His name is Viera. Officially it is Sergeant Viera and he knows this business very well. When he tells you to do something, you listen. You do not argue, even if you think he might be wrong. Follow his instructions carefully and without delay because there are sometimes very good reasons for doing things in a hurry.

‘This is a war, people, not a tourist jaunt and this man will lead you all through to the other side. Boa sorte!’

The most impassive of the drivers gathered around in Moatize that morning were the black Rhodesians. They’d heard the same story often enough, both prior to hostilities and now that conflict had enveloped much of the region.

We got to know some of them in the days that followed and they were a resolute bunch. Riding shotgun was their way of putting bread on the table and though they weren’t happy with the risk, they didn’t complain. We were to discover that there were moments when they possibly knew the ropes a little better than their youthful Portuguese Army escorts. Some had lost colleagues on this road and each one was out to ensure that mistakes of the past wouldn’t be repeated. Their heavy vehicles, many with their company names painted on them – Swifts, Watson’s Transport, United Transport, Heins and others – stood at the vanguard of the procession.

Often deployed by insurgent groups early on in this guerrilla war was what the Chinese had originally labelled the ‘box mine’. Functionary and primitive, it comprised a stock of gelignite or TNT inside a wooden box (easily constructed in a forest environment) with a simple pressure-triggered detonator attached to the lid. Step on the box or drive a vehicle over it, and boom! (Author’s photo)

A 10-ton Albion truck from United Transport’s Malawi office headed the civilian column. The driver said it was carrying Caterpillar spares and was headed for Zaire. He’d travelled the route for almost two years, he disclosed and for reasons of his own, he preferred to travel right up front.

By 10 that morning, the first army trucks that would provide our escort rumbled past. It was a hefty Berliet, heavily sandbagged around the driver’s cab. Because the hood had been removed, we could see more sandbags fitted around the wheel cavities.

We only learnt later that Portuguese convoys rarely moved about with their hoods intact. Too many troops had been decapitated by these steel sheets that were sometimes blown sideways. It stayed that way until this rough and ready antidote was semi-officially implemented.

A short while afterward, another squad of troops arrived, all in regulation camouflage uniforms. Each was armed with Heckler and Koch G-3s, standard issue in Lisbon’s African war zones and most times casually slung over their shoulders. There were also some MG-42 LMGs around. A few more troops had mortar tubes, a bazooka or two and here and there, bundles of shells neatly slotted into canvas carrying bags that they humped over their shoulder like back-packs. Just about everybody had additional belts strapped onto their webbing with grenades and extra ammunition.

Standard Portuguese Army Unimog troop carrier. The soldiers sat facing outwards so that they could retaliate when attacked. (Author’s photo)

The newcomers seemed a lively, animated lot, though there were those among them who were clearly nervous; they stayed that way until they got into the swing of things. One or two looked as if they still had a couple of years to go to make 18, never mind the ripe old age of 20.

The unit sergeant-in-charge – he was also to take his orders from Viera – was 22 and had already been in Africa for two years. Over a couple of drinks on the second night out he told us that in a stupid patriotic moment he’d voluntarily cut short his university studies to fight but just then, couldn’t wait to get home.

A short while later more army trucks roared past and pulled up nearby. An officer disembarked and barking into a walkie-talkie gave somebody at the other end a string of orders. We were ready to move, said Chagas.

The column rolled forward, a sandbagged Berliet in the van. One of the Unimog troop carriers moved into position towards the middle of the convoy, about five vehicles ahead of us. Its soldiers were clustered around a heavy machine-gun mounted on a fixed tripod on the back. An imposing width of steel plating swung about as the weapon rotated on its pivot. Moments later there was a clicking of bolts down the line as soldiers tested their weapons.

A Soviet TM-46 totally destroyed this army truck. (Author’s photo)

With another Berliet bringing up the rear, we were relieved to be on the move, but it was a tedious process, covering perhaps 20 kilometres that first day. Almost from the start, there was evidence of conflict in the area to the north of Moatize.

Barely five minutes from the railhead, our cherished tarred road ended abruptly, making for a smooth transition on a relatively level surface to rattling corrugations and potholes that might have swallowed a goat. Once on the dirt, huge swathes of dust enveloped just about everything – trucks, soldiers, civilian cars and their passengers, up our noses, into our ears and across the windscreen that needed to be wiped every ten minutes or so.

The ‘brown-out’ seemed to be suspended above ground for the duration and in that heat, thirst became our most constant companion.

Minutes later we passed an abandoned, broken-down villa, its faded, off-white walls pock-marked by shell holes and splinters of who knows how many actions. It was a scene symptomatic of all of Portugal’s wars in Africa and is still the kind of scenario you’re likely to see these days on CNN in news reports on rural Afghanistan.

A significant difference between rural Africa and Asia was that the bush around us was a spurge of tropical overgrowth that sometimes hung over the road for kilometres at a stretch. It was so thick that the guerrillas might easily have taken up their positions within touching distance of our vehicles and we probably wouldn’t have known the difference.

Minutes later, another building came into view, also partly blown apart. Chagas pointed at a window-sized gap that yawned across one of the front walls, probably caused by a mortar shell. Or an RPG-2. The building might have been used for training by the Portuguese Army, he suggested.

As the sign on the bridge warns – Zona Armadiladha- the area around the river crossing has been mined. During the course of the war many civilians died while trying to fill their water bottles at the many streams we crossed. (Author’s photo)

Suddenly more such derelict buildings came into view and quite a few displayed evidence of hasty evacuation. There were broken beds and burnt roof timbers spread untidily about outside and occasionally a burnt-out pick-up or tractor abandoned around the back. This was no training ground I retorted and Chagas didn’t reply.

Minutes later the truck immediately ahead of us, still dutifully following the convoy track, skirted a large round hole in the middle of the road. Strips of crumpled metal lay scattered along the verge. We spotted the buckled front suspension of a truck that lay discarded in the nearby bush. The rest of the vehicle had apparently been removed by an army recovery unit. Chagas offered no further comment.

The further north we travelled there were more holes along the tracks, more of the detritus of war. Twice the convoy stopped and we sat and waited as the sun beat down from a brassy sky. Even a light breeze might have eased the discomfort, but for the majority, it was sauna time. Sweat rolled off our foreheads in translucent droplets.

‘They’re checking for mines,’ said Chagas after talking to one of his colleagues who, contrary to orders, was making his way down the column on foot. And that was when he told us that he’d lost three members of his unit from mines in the past eight months, all of them while on patrols in open bush country. The tally included a close buddy with whom he’d gone through training.

A signpost on the main highway linking Beira with Lourenço Marques in the south of the country. This coastal region was rarely infiltrated by the guerrillas, in large part because the highway was surfaced. (Author’s photo)

The convoy started to roll again but our progress was more laboured than before. Delays, we were aware, were to be expected, but this was ridiculous. While we’d anticipated delays, nobody thought that the going would be so slow. In the final two-hour leg that first afternoon, we were never able to gather enough speed to shift into third gear.

Finally we slowed to a crawl, and it got so bad that somebody on foot might easily have outpaced the convoy. We futilely tried to catch a glimpse of the countryside through the tall elephant grass on both sides of the road and there was little conversation.

At one stage we passed an abandoned corrugated-iron tsetse fly control station, it, too, pitted with holes. More training? I asked. All Chagas could do was smile.

Small wonder then that tsetse bothered us. Each time one of these insects entered the cab, there was a furious session of flapping all round. Anything that came to hand became an improvised fly-swatter and for good reason: the tsetse’s bite is as painful as a horse fly.

Chagas would view our antics with amusement. To him this was just another convoy and in any event, he said, there were more tsetse flies at his base in the interior than anybody had cared to count. For the rest of the time, Lieutenant Chagas would bury his nose in the English-language papers and periodicals we’d brought with us from the Cape.

As we progressed, the rigmarole became stultifying. It was a constant round of stop and start again. We’d go a few hundred metres and the column would again slow to a crawl. In the initial leg, we might have covered perhaps five kilometres in the first three hours. Then the pace slowed still further.

It could have been worse, someone said: at least we were on the move. Once the sun reached its apogee the heat became intense. There was no other way, because we were still in the Zambezi Valley

Finally a man in uniform guided the trucks into a clearing alongside the road.

The heavier vehicles were pulled into an oblong laager, completely surrounded by bush, some so close to the jungle that there were branches pushed hard against their cabs. Buses and passenger cars were pointed to a position towards the centre, but we found a spot to park the Land Rover on the perimeter under some shade.

Meanwhile, our escort troops spilled out in groups and disappeared into a low building where only three of the original walls were still stood. It had probably been someone’s home in the long and distant past.

The structure was rickety, its roof about to collapse. In normal circumstances nobody would have gone near the place. But what was left of the structure offered a modicum of cover in an otherwise primeval terrain.