The Conflict in Depth

‘… they didn’t need logistical support. Gatherers since kids, they could live out of nothing, with a special ability to find food and water. We really had good operational results with them and we never had a desertion from the ranks of the Flechas’.

Oscar Cardoso’s testimony on the Flechas, one of the African Special Force units created in Angola after the war began: Antunes, Guerra de África: 1: 401.

At Nambuangongo, after we’d arrived, I was to discover that the Portuguese Army had implemented a bold and somewhat optimistic program of rehabilitation of former enemy combatants.

Lieutenant-Colonel Joâo Barros-e-Cunha, the garrison commandant, showed us over a village where most insurgent veterans who had come across were housed. With its distinctive tall palms, banana-leaf huts and kids playing around in the dirt, the village looked a little incongruous against a military backdrop, with the camp and its gun emplacements towering on the hill above.

The philosophy of using turncoats to fight for what was essentially a European-orientated cause – a concept, incidentally, that was later applied by the South Africans in their own Border Wars units like with Koevoet, the police counter-terrorist unit and 32 Battalion, and with considerable effect – was that every man taken prisoner was given an option. He either worked with them, the colonel explained, or ‘swish’, he drew his hand across his throat in the traditional cutthroat manner.

The choice was straightforward, he maintained: defect and start to work with the security forces against their former comrades or face the consequences. No trial, no questions, no answers.

He admitted afterwards that while that was what happened most times, it wasn’t the case with every suspect brought into camp. There were quite often innocent civilians taken prisoner but they could usually be easily spotted. Rebel military types usually wore some kind of uniform that was nothing fancy, but different from the rest. They all had boots, issue types made in East Germany and customarily with a chevron imprint on the soles, which set them aside from the bulk of the populace.

‘Might sound primitive to you, but these people don’t need coddling: they’re killers, one and all and we act accordingly’, the colonel maintained.

‘We’re at war against an enemy that is as mindless as it is brutal. The rebels never once showed compassion towards any of the Portuguese soldiers they captured, never mind civilian women and children mindlessly slaughtered at the start of it all. Their grossly mutilated and tortured bodies that we discovered afterwards – and are still finding – bear witness.’

Colonel Barros-e-Cunha waved towards an orderly and told him to get our meals ready; as always in the Portuguese Army, the only intrusion ever allowed when serious issues were being discussed was food. He went on, deeply committed to an issue that had affected his notion of how the war should be fought.

‘As you will see while you’re with us, we do things differently. We offer the hand of friendship to these people—partly because it is a Christian gesture and partly because we know they can help us win the war.’

He explained that while some of his colleagues differed with his approach, it was pointless killing everyone who opposed Portuguese rule. Granted that there were masses of civilians who had been turned against the government, but equally, many innocents were caught up in a cause which they simply did not understand because most were unlettered.

‘Essentially, the people in the bush throughout Angola are hardly likely to be able to comprehend the intricacies of modern-day politics that includes socialism, communism, capitalism or even Fascism … most wouldn’t be able to tell one from the other … they are primitive folk with their own gods and customs … their world is the bush and the ability to survive.

‘What they have been told is that Africa is theirs. And so it is. They’ve also been told by the political commissars who move about with rebel units, as much to keep their own people in check, Soviet style – as to indoctrinate the locals – that we are imperialists who have illegally seized their country.’ The nuances could be interpreted in a dozen different ways in as many countries’, he argued, using the deprivations of the American Indian and the Aborigines in Australia as examples.

‘How do you expect a simple tribesman in this jungle to counter that kind of logic?’ he queried. He ignored the political reality that that shortcoming almost certainly lay with the Portuguese themselves: the colonial tradition in all three provinces only allowed for the most basic levels of education, though he conceded that with the war, this was changing fast.1

The Colonel went on: There were reasons why some of the insurgents that had been captured were given a chance.

‘In exchange for their lives, we require them to tell us everything they knew about their former colleagues. They must give us names, places, codes, signals, dates of training, future and past programs. Also, they need to explain all the documents in their possession.

‘Some of them give us a story of sorts, but they can’t lie … we’ve enough experience to know when a man is telling the truth. If he doesn’t come clean, then he’s used up the chance we offered him … and he’d been warned…for him it’s over.’

The real moment of truth follows immediately afterwards, when the captured insurgent is expected to lead the army to his former headquarters and detail everything that went down in the operational area in which he had been active. This sometimes took in lengthy deployments of six months or more, but there were good dividends in the end.

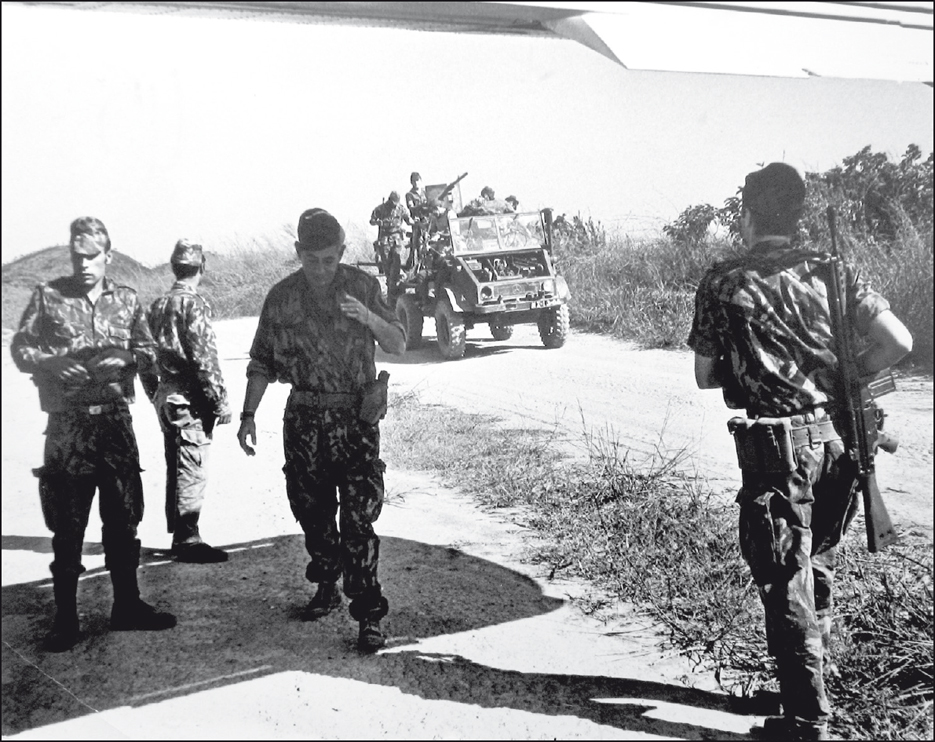

A squad of youthful Portuguese soldiers doing their national service in Angola. (Author’s collection)

‘It is here where the final showdown comes’, he declared. ‘The man takes a patrol through the jungle to his various hide-outs. He shows them the camps and other places he has used while he fought against us. He knows – and more to the point – we know that he’s going to be spotted by his old pals … they’re watching us from the jungle all the time.

‘By then they’ll be aware that they have been betrayed by this compadre, so there’s no going back. Ever …’

As the Colonel explained, if the prisoner did try to return to his old haunts, he’d be shot by his former comrades. There was no need to explain why.

‘Overnight, this former enemy combatant becomes our man and let’s face it, he’s a useful adjunct because he’s trained, he’s better educated than the rest and he clearly understands his changed circumstances. We are so confident that he will continue to help us – for he has no alternative – that we give him a gun with which to protect himself. Not just any old gun, but one of the modern automatic weapons that our own people use, the G3 in 7.62mm calibre … as good, if not better than the AK with which he was originally issued.

After lunch we ambled down the hill towards the compound housing former insurgents and the commandant smiled at a group that had been gathered together to greet our party. His attitude towards these former enemy troops was avuncular but friendly. They seemed to be fond of him, greeting us with smiles all round and waving or saluting the officers in our group.

One of the men was brought forward. His name was Alberto Imbu, a tall lad, perhaps 20 years old.

Imbu might have been younger because it is difficult to tell a man’s age in the bush: a 13-year-old often looks 18 or older and it was no secret that many of those captured were barely 14 or 15, all of them armed. It was the same in old Stanleyville (today Kisangani) in the Congo: some of the worst brutalities were perpetrated by children not yet into their teens.

Imbu had an automatic Sten slung casually over his shoulders. His dark glasses – a requisite badge of office among so many African insurgent movements – glistened in the sharp light as he spoke to us in fluent Portuguese. He could also speak French, having been taught the language by Algerian revolutionaries at Tclemen.

Yes, he had been captured by the Portuguese, he explained, with Captain Alcada translating. It had been in March 1967. He remembered it because it had been an important day in his life and the action in which he’d been badly wounded had been rough.

As one of a group of 18 insurgents who had attacked a coffee-farm late one night, he told us, three of his comrades had been killed in the same contact by Portuguese troops who came up shortly afterwards. For a short while they had been trapped, with a fast-flowing river behind them and, it being night, none of his colleagues were prepared to take the chance and swim for safety. That was when they took most of the casualties, including quite a few wounded.

He’d been patched up at one of the local hospitals after he’d indicated a willingness to cooperate and had subsequently led the authorities to his former camp. That gesture resulted in Captain Alcada’s squad killing still more of his former comrades.

No, he replied when I asked him, he had no regrets. He had his wife and children at the camp below and was confident that he could look after himself.

Was this his original wife? No comment. And his children? Again no comment. All the while as he spoke, Imbu patted the elongated magazine on the Sten.

We were later told that this man had shown great courage in several recent actions and had been made a section leader, to which Alcada added, ‘he’s a good fighter …, tough, knows the ropes’. I only learnt afterwards that his name had been put forward for a decoration for a brilliant piece of work in destroying an enemy supply column some months before.

‘These former gooks are a very good second arm to our forces’, the captain told me later, though he admitted that the possibility of some of them being double agents was not impossible. ‘We infiltrate their units, they ours …’

We were discussing problems linked to employing erstwhile hostile elements to handle tasks that might be problematic, such as being entrusted with sensitive intelligence. There were easily more than a thousand of these turncoats in the Angolan war, he admitted, and while they were a priceless adjunct, there were very few Imbus within their ranks. Most were basic foot soldiers, former insurgents that were illiterate and not all that motivated, whatever the cause.

‘But they know the jungle. They are familiar with many of the foibles of their old buddies.’ Most important, he declared, ‘they know every ruse and that is invaluable’.

The captain told me of a 16-year-old he’d captured on one of his raids. ‘We’d caught this young fellow—only a boy—about 10 miles south of Zala. He’d been a member of a pretty competent group of insurgents operating in the area. We were lucky to catch any of them alive—they’d been trained by the Chinese and had been instructed to fight to the proverbial last, he added.

‘Having taken him in that battle was only half the battle won. His colleagues knew we’d got one of their people and they were going to do their best to get him back— or at very least try to kill him before we could get to work on him. Consequently, they were right on our tail as we headed home. At one point our lead scout came in and told us that they were perhaps 30 minutes behind us.

‘The trouble was, we still had a difficult march of several hours to get to the road where, hopefully, we’d be picked up. Bottom line was that we’d have to move quickly. I’d already radioed base and told them what we had … asked for a helicopter but there weren’t any available. I’d considered an ambush, but we didn’t have the numbers … this was a large force we were up against … also, they were all MPLA … knew all the tricks in the game’.

‘So here were we, in the depths of the African bush, running for our lives. Meanwhile, this little shit was making things difficult for us.

‘At first he refused to walk fast, as we required of him … he’d drag his heels between the two soldiers delegated to march on either side of him. Then he complained that he couldn’t keep pace because his arms were bound. Granted, I was aware that he’d fallen face-forward a few times because the undergrowth was vicious and sometimes reached right across the paths we were following.

‘Our guys pushed him ahead anyway, clipped him across the head when he became difficult but none of it helped. He obviously knew his buddies were on our trail.

‘I knew that if we didn’t improve our pace, the guerrillas would double around, as they often liked to do and we’d be ambushed. These people knew their own back yard and all the short cuts. We were in a fix, which was when I thought that perhaps I should do the obvious and whack the guy.

‘Eventually I took the boy to the side and spoke to him. He’d been educated in a mission school so he could speak fluent Portuguese. I told him that he was holding us up and that if he continued playing games, I’d kill him … .simple as that! He was placing us in jeopardy, I said, and rather he died than we did.

‘The little bastard was sceptical to begin with. He’d heard stories about us needing people like him. He kind of suggested that we wouldn’t simply kill somebody for not cooperating, and that we needed him more than he needed us. At that point I warned him that he was wrong, adding that I was more interested in saving the lives of the men with me than anything he might be able offer.

‘But even this didn’t have any effect on him and he refused to talk. He just stayed sullen and stared into space.

‘At that point I told the sergeant to cut his restraints, so he would clearly understand that this was no idle chatter.

Portuguese officers discuss tactics under the wing of a Dornier spotter plane on the Nambuangongo air strip. (Author’s photo)

Things improved a little once his arms were free, but he still answered in spurts. He said he was going to die anyway and that there was no difference whether it happened out there in the jungle or later at the hands of some of the Portuguese torturers who were waiting for him. “Death was inevitable—one way or the other”, were his words. He was either a very brave young man, I concluded, or a very stupid one.

‘Well, when you have something like this on your hands in the middle of nowhere and the enemy is breathing down your neck, the consequences are usually terminal. I told him so. Again he looked past me and stayed mute.’

That was when captain Alcada took a chance. He asked the boy whether he would believe anything he said? Anything?

‘I asked him whether he’d accept the word an older man, an officer. This caught him by surprise. “What do you mean?” he shot back.’

Alcada told the boy that if he came voluntarily, he, as a fellow-soldier, would promise him his life. On the other hand if he kept up the charade, it was over. By coming of his own free will, the captain said he would personally take up his case.

‘I gave him my word—one soldier to another – were the words I used. Obviously I’d already overstepped the line by making a declaration of faith with the enemy. Everything went quiet for a moment because just about everyone in the squad – apart from the men that had taken up positions on the periphery – was listening.

‘We could see that he was hesitant … more puzzled in fact, probably by me treating him as an equal, though I’d imagine that my right hand fiddling with the pistol on my belt must have played a role in him finally making a decision. Which was when he answered: ‘yes, I’ll come!’ That astonished us all.

The young insurgent had been told by everyone he’d ever met while under training that the Portuguese were a crafty bunch of bastards, so it was a big decision. Alcada also accepted that the boy wasn’t stupid: he’d been offered his life instead of being shot, a pretty realistic option under the circumstances.

‘We lost more time so now we had to move fast. I told the youngster to get himself together and move off, right behind me. I said I wasn’t going to bind his arms again, which was about the best thing I did because that in itself was a gesture of sorts.

The captain’s patrol didn’t make contact with the enemy again, probably because they moved at the double for the rest of the long haul. Before nightfall they were back in camp.

I was to learn only afterwards that that young fellow was actually in Nambuangongo when we were there, helping to build the new school. He also had one of the young conscript officers helping him with his secondary school studies.

Alcada: ‘He’s bright. Probably go far. If he keeps on like this, he’ll probably make university, especially since I’m on his case. It’s a debt of honour, I suppose…

After a month covering that African conflict, that event in a remote military base in the Angolan jungle was one of the few positive things to emerge in a war that seemed to offer little for either side. We subsequently heard that whenever Alcada passed though Nambuangongo, he’d spend a little time with his young protégé and if circumstances allowed, would take him books and magazines. When his second two-year period of duty was over, he promised the youngster that he’d look into the prospect of more advanced studies in Luanda—or perhaps even Lisbon.

I never heard the outcome of that little episode, or perhaps captain Ricardo Alcada wasn’t telling. When I saw him in Cape Town afterwards, he told me that Imbu – the young guerrilla fighter with the Sten gun that we met on the first day – had died in a road ambush three or four months after our visit.

In the six months that captain Alcada had been back on active duty in Africa, he’d been in about a dozen contacts with the enemy. These were major actions he said, not just the kind of casual shots that ring out from when a convoy passes. Each time he’d either been ambushed, or he’d set one.

During this time, his group, 166 Company, had killed 15 and captured 37. They had also taken more than 50 weapons, almost all automatic and mostly of Russian and East European origin.

Pendra Verde – the ‘Green Rock’ – was a significant guerrilla redoubt in the Dembos north of Angola until it was retaken in September 1961 by government forces. It was a difficult action across high ground that cost lives on both sides of the line. (Photo Manuel Graça)

Since he had returned to Africa, his group hadn’t lost a man in action, and there were quite a few wounded. One of his corporals was killed in a road accident and another badly wounded in the shoulder and evacuated to Luanda. Lighter wounds were treated at the field hospital.

‘They’ll get better sooner or later and are perhaps wiser for the experience’, he commented with characteristic aplomb when we discussed casualties.

The captain was proud of his record. Though his adversaries might disagree, he had good reason to be. The fact that he had taken a number of prisoners underscored his often-voiced theory that the Portuguese should take the war to the enemy. He was dismissive of any kind of prevarication or what some Portuguese officers liked to call ‘alternative action’, which was largely defensive-based.

Alcada had been operating mostly in an area between Zala and Nambuangongo. This area, he said, was slowly being cleared of insurgents, though I was not sure how anybody could really be certain of what was going on in some of the most forbidding rain forest on any continent. The jungle stretched more than a thousand miles northwards, all the way through the Congo and on to the Central African Republic, Gabon and beyond. It was the same throughout: a dark, overwhelming hinterland that had never taken kindly to human incursion. The area around Nambuangongo was no different.

Pilot’s-eye-view of an army base in Angola’s embattled Sector D. (Author’s photo)

The captain believed otherwise. He thought he knew what was going on in his modest fief and was proud of his role as a counter-insurgency tactician. He would comment succinctly that the secret was in getting your hands dirty. ‘Remember, this is never pleasant work. It is not, as you Anglo-Saxons say, nice. But it is war and lives are lost. You’ve to get out there and do what needs to be done to win it.’

He had his own views on the outcome of the kind of modern guerrilla conflicts being fought at the time, both in Africa and Asia. The captain was outspokenly critical about what was going on in Vietnam where, he said, the Americans, because of Washington politics, were fighting a rearguard action.

He maintained that the hostilities in which Portugal had been thrust could only be won if the conquest was both military and political. You have to achieve victory both in order to win at all, he would stress, though he was never prepared to discuss the role of his own politicians in his African struggle.

The French in Indo-China, he would say, lost both militarily and politically; it was an utter disaster. In Algeria they beat the FLN in battle, hands down as the English say. But then they went and lost the sympathy of the civilian population. That too, was a debacle. The FLN at Evian were a broken military power, but De Gaulle was shrewd enough to realize that he could never win the Arab population to his cause. ‘That’s why he pulled out’, the captain added.

There were two examples of modern guerrilla warfare he reckoned, where the insurgents were beaten both at political and military levels; in Malaya against the communists and in Kenya against Jomo Kenyatta’s Mau-Mau.2

‘And that’s exactly what we are trying to do in Angola—follow the British example and get the upper hand in both the military and political spheres. The first we are accomplishing, of that you see the evidence here in Nambuangongo, Santa Eulalia and elsewhere in Angola. But it’s a race against time and the MPLA for the second.’

Trouble was, he added, there were other nations involved in this fight. The idea of having South African troops in Angola would cause a flurry in Third World politics, especially among the Afro-Asians.

‘But the Afro-Asian powers say nothing about foreign powers helping the insurgents … if you examine this war carefully, you will see that we are fighting, one way or another, just about every major power.

‘The war started with dollars. The Americans thought that by backing Holden Roberto they would chase the Portuguese out of Angola within months—like New Delhi did, when the Indian Army overran Goa. What they still don’t realize is that we, like De Gaulle, knew long before the final strike, that Goa was lost.

‘We couldn’t possibly win against a nation of 450 million people which has the backing of every major power in the world. But here in Africa, things are different.

‘The Americans now accept that they might have made a mistake, but they’re still allowing money into the Congo from a number of organizations in the United States. There are American church and social groups and others in Britain and more in European and Asian countries passing on money to guerrilla groups—over and above what they receive from Iron Curtain states.

‘The rebels wouldn’t be able to keep on with the war but for this financial aid’, Alcada maintained.

‘Fortunately, a lot of it seems to be finding its way into private pockets and no doubt effecting the resources of the ‘Freedom’ armies, but then, let’s face it, that’s the African way, n’est-ce pas?’

It was his view that that since the Organisation of African Unity [African Union] had taken over the finances of the rebel group UPA, the amount for their war effort had decreased. ‘Last year Roberto complained bitterly at one of the OAU conferences that he was receiving less financial assistance now than his people got in 1965.’

‘Obviously there are a lot of people cashing in on this war—but then we don’t mind— the more the merrier’, he quipped.