Cabinda: the War North of the Congo River

‘One of the most significant aspects of guerrilla warfare is the manifest difference between information available to the guerrilla and that available to the enemy.’

Ché Guevara, on his return to Cuba after visiting

several African conflicts, including the Cabinda Front

The war in Cabinda – the oil-rich Angolan enclave north of the great Congo River, differed radically from guerrilla campaigns being fought against the insurgents in either the Dembos or, for that matter, in the east near the Zambian or Katangese frontiers. Things were also very different to what was going on at the time either in Mozambique or Portuguese Guinea.

If the Dembos was regarded as forbidding, this northern region, lying adjacent to the equator, was much more so. Conditions weren’t helped by an overwhelming, almost-asphyxiating tropical heat that made people listless, somnolent and insecure. It was the kind of environment that within days, would cause all the clothes in your suitcase to grow a kind of scum-coloured mold that sometimes proved difficult to deal with. It was also a time when air conditioning – as you and I know it today – was still waiting to happen throughout much of West Africa.

Perspiring, out-of-breath, European-born Portuguese troops were aghast within minutes of stepping out of their aircraft when they first arrived, largely because they had never experienced anything like it. Few were likely to recall that early navigators had given Cabinda and French Equatorial Africa – including nearby Congo (Brazzaville) and Gabon – the unflattering handle of Fever Coast. British traders in Nigeria were more colourful in their use of idiom and ‘White Man’s Grave’ lingered for decades after quinine was found to be a reasonable counter to malaria.

As with British Forces in Malaya in the 1950s – and the French and Americans in Vietnam – it didn’t take these young soldiers long to get used to it all, for no better reason than they simply had to. In any event, conditions were light years from today’s much vaunted humanitarian approach to human frailties under fire that often includes a range of specifics for any kind of stress disorder. To the majority in those faraway days, PTSD might have been a galaxy in the firmament.

A soldier who suffered mental trauma or who was possibly emotionally unstable in those days, was much more likely to find himself in the brig for malingering than before the unit doctor.

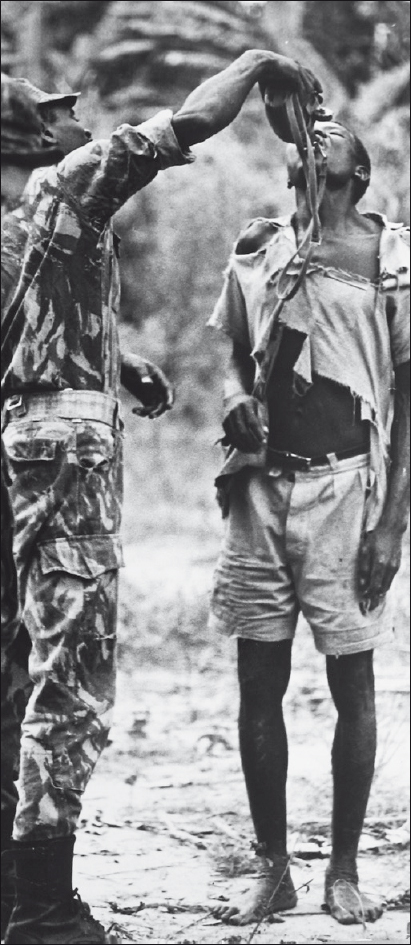

An early photo of the war when the Portuguese first moved in to retake the jungle north from an invading guerrilla force. (Author’s collection)

The concept was adequately illustrated when American General Patton struck a GI at a hospital in Sicily. The soldier had no physical wounds, but he was just as much of a casualty as those who did. It says it all that in the First World War, only 30-something years before, such people were often placed before a firing squad for cowardice in the face of the enemy.

In Cabinda, the actions of small guerrilla units arrayed against Portuguese authority were dictated first by the jungle and then by their weapons, the need for food, the deployment of their adversaries and finally, instructions from military command in Brazzaville—in about that order of priority. The result was that this jungle campaign differed radically when compared to similar military struggles then being waged by the rebels further towards Angola’s south.

It was a two-edged sword. The Portuguese faced the exact same privations, only they were better organised. This was one of the reasons why Lisbon was so successful in the oil-rich territory, a tiny spit of land about the size of Vermont and completely surrounded by independent African states that were virulently anti-Portuguese.

In the years before I got there on my ‘official’ visit in late 1960s, the Portuguese army managed to recapture all the territory that had formerly been under insurgent control in the enclave. It was no easy task, because following the initial onslaughts of March 1961, rebel insurgents managed to occupy more than 90 per cent of the enclave. They did this in a single, concerted sweep towards the coast from about eight or nine different entry points, the entire operation dictated by an MPLA chain of command then headquartered in Brazzaville.

The guerrillas overran villages and towns in the north-east and, as with the Dembos further south, they brought all commercial activity, logging, oil drilling and agriculture to a standstill. They were even more successful in routing an ill-prepared Portuguese militia and police north of the Congo than they’d been to the south of it and stopped just short of the capital, Cabinda, itself.

It was only a concerted effort by the Portuguese army, backed by whatever air support could be mustered that enabled the authorities to reverse this tide.

It took another four years before the country was manageable again. Although the insurgent threat in Cabinda thereafter remained negligible, largely because the MPLA was replaced by other, less determined liberation groups, you still needed to travel in convoy between all the major centres.

As a journalist in transit, I saw a little of the initial struggle when I briefly passed though Cabinda Airport in December 1964. At the time the place was ringed by machine-gun turrets and American-built T-6 Harvard trainers with loads of rockets, bombs and machine-guns were landing and taking off. The atmosphere in town was tense and the man in the street projected a nervousness that I had only previously seen in the Congo and at the height of the OAS-FLN fracas in Algeria.

Unlike my visit three years later, few Portuguese Army officers appeared to have much time for anything but the war. There was a real threat of being driven out of the enclave, which today ranks potentially as the fourth or fifth largest oilfield outside the Americas.

Major Mathias concisely summed it up: ‘It was close … too damn close … the terrorists never realized how close to victory they really were.’

It has always been this apparent lethargy or lack of interest – or rather, ignorance of what was going on strategically in an operational area – that almost consistently let insurgents down. Patently, they lacked the infrastructure for an efficient intelligence set-up, not only in Cabinda but also in Sector D and in the east. This should never have happened because the East German intelligence specialists trained scores of MPLA cadres. These shortcomings, critical under the circumstances, repeatedly caused the guerrillas to play into the hands of government forces.

In Cabinda, they caught the Portuguese authorities literally, with their pants adrift. Yet as hostilities in the enclave progressed, they were not even aware of the damage they had caused. Nor did they have either the leadership or the initiative to launch that final push. Even Lisbon conceded afterwards that the rebels were a hairsbreadth from snatching victory, saying that perhaps it was the heat.

A reason for this, put forward by military strategists who studied Portugal’s wars in Africa in more recent times, was that throughout their African campaigns, the Portuguese were tardy in releasing anything specific about what was going on in their African military theatres of activity. The Lisbon-based Lusitania News Agency would make its weekly declaration about casualties, promotions, retirements from the three services and possibly something notable about an action that might have warranted a decoration for bravery, but little else.

The media railed, the government gave the stock retort of ‘no comment’ and the military authorities were castigated by the international press corps. But then the Portuguese always seem to always have marched to the beat of a different drum.

Remember, this was a time when just about everybody and his brother could arrive in South Vietnam and, on demand, be given press accreditation by the Americans. All you needed was the price of a ticket to head for Saigon and become a ‘war correspondent’. North Vietnam was much more sensible and played it like the Portuguese, and almost no foreigners covered the war from Hanoi.

When the Falklands War came along, the few British journalists who managed to cover the war were initially astonished at the level of media control instituted by their minders. If they didn’t like military censorship, one and all were told, they were free to go. In the end, it worked very well.

For better or for worse, the Portuguese were remarkably successful in keeping the war out of the news, and here Vietnam also helped. Through the medium of television, half the world was able to watch this South East Asian conflict from the comfort of their living rooms, and as might have been expected, nobody gave Africa a second thought. Why should they? They already had a surfeit of helicopters going into combat, jungle patrols and all the blood and guts and gore of a real war.

There were some newsmen allowed to visit the fighting zones in Angola, Mozambique and Portuguese Guinea, but all were carefully screened. Apart from Portuguese scribes, Jim Hoagland of The Washington Post got into Portuguese Guinea, in part because of diplomatic pressure from Washington. The same with Peter-Hannes Lehmann of Der Spiegel and perhaps a few dozen others over more than a decade.

Those of us based in South Africa found things a lot easier, largely because Lisbon relied on Pretoria for advice as to who was acceptable. In any event, it was a simple matter to travel from Rhodesia to Malawi on the open road, and there were no restrictions. Long before you reached Tete on the Zambezi River in Mozambique, you were able to see aspects of the military dimension from up close.

On my part, having already covered the troubles in the Congo and Biafra, my bona fides were taken for granted. But even then, I was only allowed limited access.

Major Mathias conceded that the ‘security blanket’ as he would phrase it, was a complete reversal of the immensely successful Biafran propaganda programme which was handled by a public relations concern in Geneva.

The Swiss company Mark Press helped create universal support for Biafra’s millions of starving children. Indirectly, according to Frederick Forsyth – who covered that debacle from the beginning – the emotional storm generated by hordes of little ones with bellies swollen from kwashiorkor and dying by the hundreds each day ended up being ghoulishly beneficial to the Biafran leader, Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu. The same kind of thing took place afterwards in Ethiopia, only this time it was my old pal Mohammed Amin who spread the word with his heart-wrenching pictures that eventually got him acclaimed by the Queen, President Reagan, the United Nations and others.

A Portuguese soldier gives one of the locals a drink from his canteen in the Cabinda jungle. (Author’s photo)

The first book to appear in the West from the Portuguese perspective, The Terror Fighters, was written by this author. On the guerrilla side, the radical British writer Basil Davidson went in several times with the rebels and produced some notable volumes of his own, including The Eye of the Storm.1

By far the best must still be Angola, written by Douglas Wheeler and another old friend, René Pélissier. That work was published by Pall Mall in London in 1971, though Portuguese Africa (Penguin) by J. Duffy rates good mention.

In Lisbon’s African campaigns, by releasing only essentials and remaining almost totally non-committal about just about everything else, the media played a relatively insignificant role as these African hostilities progressed.

On the one hand, the Portuguese public was spared many of the gory details, though that kind of obscurantism ended up being defeatist. When the 1974 evolution took place, the entire nation was taken by surprise because they had no idea how bad things really were, in Portuguese Guinea especially. On the other hand, there was a limit to marginalising issues indefinitely, especially since the casualty lists spoke a language of their own.

On a more fundamental level, by saying nothing about a major insurgent strike in a sector—an attack that may have been months in the planning and which cost a mint in equipment and men – Lisbon was consistent in maintaining the upper hand in strategy. The lack of any news about guerrilla successes must have a severe effect not only in demoralising the rebel command but also on their men in the field.

‘Put it this way’, said the major. ‘The insurgents hear nothing for weeks or even months about their great battle. They have no means of finding out either because radios in the jungle are at a premium, and the few that there are cannot be operated because the operator has been inadequately trained or the batteries have been drained by jungle damp.

‘Even worse, had somebody in Brazzaville known the true story, somebody might have been able to organise a follow-up activity that may have delivered a coup de grâce in a particular sector.’

Major Mathias continued: ‘This is basic incompetence, nothing else. For now a new bunch of guerrillas is going into battle not knowing what to expect. They have heard claims of victory, but these cannot be substantiated either by displaying captured Portuguese soldiers, or even by showing photographs of installations or equipment destroyed.’

It was all very well to broadcast weekly reports of 68 Portuguese soldiers killed in this action and 14 aircraft downed by the intrepid comrades in another – Brazzaville Radio was regularly putting out that kind of propaganda – it was something else to show proof.

Like the old adage, said the major: ‘one picture is worth a thousand words.’

‘So when one has had years of this drivel, even the most seasoned supporter of Freedom Army ideals becomes sceptical. This was one of the reasons why so many former Cabinda nationals have returned to their homes from across the border … they didn’t know whom to believe in the end…’

Another officer attached to the Cabinda commandant’s staff said that perhaps the biggest single cause of desertion among the guerrillas was the number of wounded who were ferried back across the frontier. Most were taken out of Cabinda on primitive litters, often with arms or legs blown off. Others were brought in suffering from third degree burns as a result of napalm, though Lisbon consistently denied use of this weapon.

‘Our pilots see these convoys moving through the jungle … they report in, but the order comes back: let them go.

‘The fact that they take their wounded back to base does us a lot more good than harm. Anyway, we’re not keen to stretch our own medical services by treating people who would have little compunction in castrating Portuguese troops they find wandering about the jungle, which has happened often enough in the past’, the officer suggested.

Anyway, he added, the Cabinda people were weary of war. ‘They’ve had almost a decade of it and all they want now is peace. They also resent many of the demands made by the terrorists—and that is why local chiefs have been willing to co-operate with the Portuguese authorities in recent years.’

On a broader canvas, there was little doubt that the war in Cabinda had wound down considerably from the intensity of the earlier years. There had been almost no insurgent activity within 50 kilometres of the town for some years.

The few sorties that took place were restricted to the far north, though occasionally the insurgents would ambush a patrol or a vehicle. Often as not they were happy to enter the country, wander about for a few weeks and return home again, with the usual stock of hair-raising exploits and conquests which were dutifully repeated on Brazzaville Radio.

For all that, the Portuguese authorities in Cabinda had one persistent problem which had caused problems over the years—the ill-defined frontiers with the two Congos. These are what we know today as the Democratic Republic of the Congo with Kinshasa as its capital and the quasi-Marxist Congo (Brazzaville) on the north bank of the river they both share.

Even before the war, smuggling was a major commercial industry in the enclave. Traders from Brazzaville and Leopoldville would bring through quantities of cheap watches, cameras, silks, French perfumes and other items that were heavily taxed in the Portuguese provinces. In return they would go back with stocks of canned goods, condiments, raw coffee and goldware which could be sold for as much as 200 or 300 per cent profit in the former French and Belgian colonies.

Similar frontier problems exist today, Major Mathias said; only now it becomes more serious when a Portuguese patrol is on the trail of an insurgent band and they eventually catch up somewhere near the border.

‘What does a man do then? We know vaguely we are near the frontier, but that’s hardly the end of it. We go on and, if we can, we destroy. The insurgents invariably claim that we had acted against the precepts of International Law and that we had sent our troops into Congo-Brazza or Congo Kinshasa territory. But who is to prove one way or the other in the middle of an undefined, uncharted jungle?’ the major asked.

He said that similar problems existed along the frontier with Zambia. More than once, President Kenneth Kaunda, the Zambian president, had taken the matter up with the United Nations. ‘Then we’d have the wrath of the world on our shoulders for a week. And nobody stops to think for a moment that it could be the other way round.

‘The terrorists are given carte blanche to cross any border they please to attack our people … the Portuguese are never able to retaliate…’

Frontier problems in Africa were a heritage of the colonial era and in the 21st Century, they still are.

There are other difficulties involved in border claims elsewhere in Africa, like the Bakassi Peninsula, currently in the public eye. One is a tiny stretch of land that straddles an isthmus between Nigeria and the Cameroon claimed by both countries, to the point where their armies have moved closer. The dispute goes back well into the last century when the scramble for Africa by the former European colonial powers was intense, the only difference between then and now is that Bakassi holds rich deposits of oil.

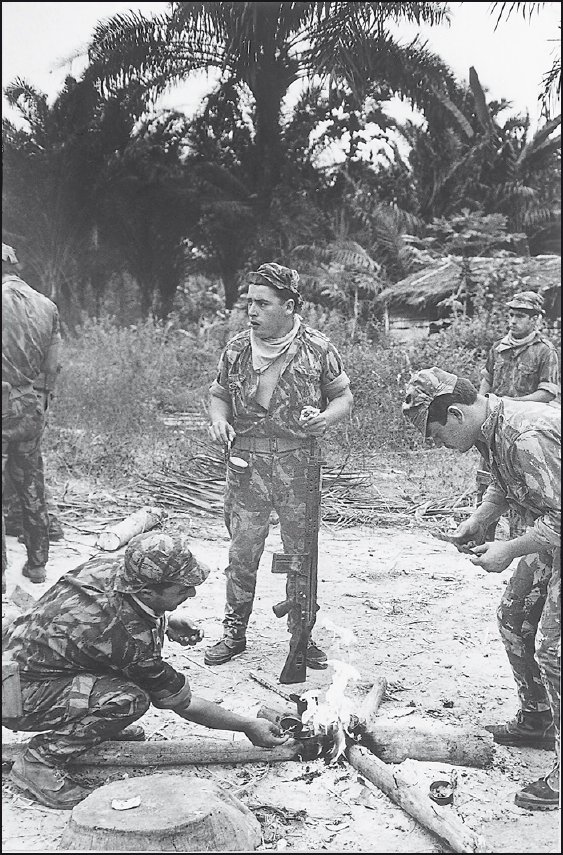

Portuguese marines coming ashore after an operation. (Author’s collection)

There is a plenitude of such issues facing contemporary African governments. Lines of longitude and latitude defining frontiers were drawn arbitrarily across the map of Africa over conference tables in the various European capitals, with little regard for natural or geographical limitations such as rivers, mountains and deserts.

‘The hardest hits were the tribes, and in Angola’s Bakongo people, we have a typical example. Half the tribe lives in northern Angola, the other half in the Congo. A similar problem exists here in Cabinda’, the major explained.

‘There are few of the local population who have not got at least one member of the family living in Congo-Brazza. Everyone living on this side of the border can trace family links with someone over there.’

I was to see this later for myself. Many of the African villagers I met near Dinge and Belize in the interior spoke fluent French as well as Portuguese and their native tongues. A number had been educated by the French, as in the case of Corporal Mavungo, a Portuguese war hero.

Corporal Vincente Mocosso Mavungo, a native of Cabinda and a corporal in the Portuguese army was awarded the Cross of War, Third Class, for bravery while under enemy fire on Portugal Day, June 10, 1968. The action had taken place almost a year before and at the Luanda ceremony, Mavungo and other war heroes had been the toast of Portuguese newspapers on three continents.

Altogether 25 Portuguese combatants from the army, navy and air force – including four more Africans – received their decorations from the heads of the Portuguese Armed Forces in Angola. In order of merit, Mavungo’s decoration was the fifth highest awarded by the government that day.

Corporal Mavungo’s story was indicative of the way the Portuguese fought their wars in Africa. The event took place during a classic guerrilla ambush in tropical forests so dense that the Unimogs the troops were escorting had their lights on. In parts, tropical foliage completely covered the road, cutting off almost all the light from above. Conditions were ideal for an ambush, the squad had been told by their sergeant earlier, to which he’d added, ‘so be careful …’

In charge of a handful of troops on the second of four Unimogs, Mavungo took up a position behind a heavy .50-calibre machine-gun fixed to a tripod on the rear of the truck. There were no Panhards for back-up and under those conditions there would certainly be no top cover, even if there were any helicopters available.

Most of the men on the vehicles sat with their legs hanging over the side but it wasn’t a comfortable ride because they continually had to give way as large clusters of bush sheered past. Meantime, the jungle darkened still more.

It suddenly became light as the trucks skirted a mangrove swamp and a pungent odour of putrefaction enveloped the convoy. Moments later a black swarm of tsetse flies arrived. Everybody cursed because it was stifling. Sweat speckled the faces of the men and they constantly had to swat both mosquitoes and flies, which eventually became so plentiful that even with the heat, the driver and his mate turned up their windows. A minute or two later, the column was in the jungle again and most of the insects disappeared.

According to Corporal Mavungo, they travelled like this for another five minutes or so when a group of guerrillas opened fire from a well-constructed hide to the immediate right of them.

Almost simultaneously a powerful explosion ripped open part of the roof of the cab of the first truck in the line. The vehicle lurched to a halt in a crash of splintered glass and screams while the driver of Mavungo’s truck – taken completely by surprise – drove into the rear of the vehicle ahead.

The corporal’s two comrades, one on either side of him, fell off the truck and were dead before they hit the ground.

The other two men still alive on the rear of the Unimog, joined their corporal at the base of the machine-gun. They could hear the two men in the cab groaning, though they weren’t sure whether they’d taken hits. The ambush had been well planned.

By now there were only two vehicles countering the guerrillas firing from the nearby jungle; the last two trucks in the column had swiftly reversed and were out of sight. So much for back-up, thought Mavungo. The men on the back of the lead truck were still firing, though it was sporadic, because some of those men had been wounded.

The war became a rather relaxed affair when there was supposed to be no enemy around. The convoy would halt in a clearing and food and drinks would be hauled out. (Author’s collection)

For a few moments a single thought echoed though the corporal’s mind— how many of the enemy were there?

His training had long ago taught him to shift the safety catch of his G-3 to ‘rapid-fire’ in an emergency. Within seconds he had used up two clips, spraying the jungle in the immediate vicinity of the truck. He spotted green tracers bouncing off the bodywork around him. This was MPLA, he thought.

A grenade exploded to the rear of his Unimog. Something hot touched the corporal’s back high up, between the shoulder-blades. The touch turned to fire as blood trickled down his spine. He had been hit. He had never been wounded before.

The firing slackened a little after he’d emptied another magazine into the jungle and just then, a searing pain shot across his cheek as a fragment of hot metal grazed his face. He cursed in his native Kikongo. Spasms of a racking, throbbing pain pushed all other thoughts from his mind. Another explosion nearby brought his predicament into sharp focus once more. He was out of ammunition, which was when he moved towards the grenades on his belt.

As he pulled the last pin and hurled the khaki-coloured canister that looked more like a can of shaving cream than a bomb, he jumped from the truck. Moments later he felt for the grenades of the two dead soldiers, found them and took their ammunition clips as well.

Though the firing had intensified, he did the same with the two wounded men up front and finally returned to his crouching position under the heavy plating of the machine-gun turret where he continued to retaliate.

Only minutes had passed since the start of the action and already the corporal sensed a weakness in his arms and legs. Blood was running down his legs…must be a bad one, he reflected. Worst of all, he seemed to be fighting this war on his own. From his partly-protected position he thought that others on the lead truck might still be firing, but he couldn’t be sure.

What to do now! He’d used up his ammunition, and all the available grenades. He wavered momentarily. A vision of emasculation that he had seen so often among victims of previous actions flashed through his mind.

Corporal Mavungo looked up at the gun above him. Dammit! He thought … that gun was waiting to be used. His mind had been so concentrated by enemy fire that until then, the obvious solution had evaded him.

Slowly, painfully, the black soldier dragged himself towards the gun and slumped against the canvas straps. All he could do was swing it around on its pivot and fire. When he had exhausted the first belt in the breach, the corporal collapsed unconscious.

It was in this position that the men on the two remaining army trucks, having heard the firing slacken, gingerly moved forward and found him. There were also two badly wounded colleagues who had survived; the rest of the men, including both cab crews, were dead.

Around the Unimog in the nearby jungle they found the bodies of eight dead insurgents. One of the men was later identified as a prominent insurgent section-leader from the Congo (Brazza).

The ambush that Corporal Vincente Mavungo survived was not something isolated in Portugal’s African campaigns. Such incidents were taking place each day in all three theatres. Increasingly, it was black soldiers that were in the thick of it

Over the previous five centuries, Lisbon – as with the Spanish in South and Central America – had always made good use of indigenous soldiers to protect their interests in the interior. There was never a shortage of volunteers among the more bellicose African tribes in either Angola or Mozambique, where combatants with a modicum of training were employed to full advantage to impose the will of the so-called Motherland. Nor was it any secret that like the British in their domains, legions of Portuguese administrators over the centuries had been shrewd manipulators in playing off the designs and passions of one tribal group against another. Divide and rule was as much a part of Lisbon’s colonial philosophy as of Perfidious Albion.

Many of the African troops in Portuguese army uniforms in Angola were Kimbundo and Bailundo tribesmen from the south who had centuries-long records of antagonism towards the northern Bakongo and Kioko who made up the bulk of the guerrilla forces. Hatred between these ethnic groups was mutual, brutal and ingrained in tribal lore and legend, in much the same way as the Hausa-Ibo internecine feud in Biafra was based on a century of intertribal strife.

In those days there were no cell phones; i-Pods and the computer-age still lay ahead. Our cameras were not digital and we used film – lots of it. Which meant that even when you came under fire in this and other wars, you needed to change film in order to get your pictures. The author on a troop carrier in the Angolan jungle doing the necessary taken by Cloete Breytenbach.

Above all, Portuguese authorities readily acknowledged, they would never win that war, or their campaigns in Mozambique or Guinea, without the help of their African allies, as they liked to call them. Which was why Lisbon cultivated a series of alliances with bellicose tribes like the Makonde in Northern Mozambique and the Futa-Fula in Guinea.

‘This is an all-colour war, senor’, one of the top military commanders in Luanda told me when I questioned him about Mavungo.

He continued: ‘The multi-racial Portuguese troops are fighting an African enemy controlled by Africans and a sprinkling of non-Africans. For our part we cannot afford any distinction on the lines of colour. This war can be won only if all races in Angola are as one against an adversary that is backed by two of the world’s great powers—Russia and China.’

Another officer elaborated on a theme that was increasingly making the rounds in Luanda: ‘We will eventually make Angola into the Brazil of Africa. Luanda is our Rio and the forests as far north as the Congo our Matto Grosso. When we eventually succeed, and we will, mark my words, this will be one of the great countries of Africa and the world. This will not be an overnight transition. All we need is time … a little more time.’

At Cabinda, we arrived with the mail and the bags were a priority. A truck was brought on to the tarmac and once loaded with its precious cargo, it sped off into the city, horn sounding. Everything else in this war could wait, but not the mail.

Another man onboard our Noratlas freighter, a young infantry officer, was reminded of a related incident that had taken place while he’d been based in the Cazombo region, between Katanga and Zambia in the east.

His unit had captured a group of insurgents during a battle. There were about six or eight of them, he said. While they were waiting for a plane from Luanda to remove the prisoners for interrogation, they were kept under guard in an old grain silo. ‘We’d had them with us for about four days’, he continued.

It was not long before the plane arrived. Almost the whole camp turned out to watch it touch down. As soon as the aircraft was brought to a halt the mail was thrown out of the cargo door and the distribution of mail began.

‘Word quickly went through the camp that letters from home were being distributed at the airstrip. Everyone came running. Even the two men who were supposed to have been guarding the captured terrorists.

‘All six of them got away. We put out a drag-net for days, but they were gone … probably still fighting in Angola somewhere … so much the wiser for their experience’, he reckoned.

Major Jorge Mathias, staff officer to the commandant of the territory met us on our arrival at Cabinda airport, which is used by both civil and military aircraft.

A jovial, good-humoured man with a passion for horses which had not been dampened by the tropics, Major Mathias had only a few years previously been one of Portugal’s best-known international show-jumpers. He knew the British, Argentinian and South African equestrian fraternity well and said he missed the keen-edged spirit of competitive jumping wherever it was being held at the time.

From the airport we were taken through town to the officers’ mess and discovered a clean, neat and well laid out little city. The double-storied whitewashed building stood unobtrusively in the shadow of a huge new American-type tourist hotel, built, we were told, with the needs of local oil-interests in mind.

‘It’s a growing town, all because the Americans discovered oil’, the major joked. He said that although the oil finds had brought undreamt wealth to Portugal, it had seriously affected the pocket of the ordinary man in the street. Rents for the kind of house an American oil executive or his deputies would hire had gone up tenfold. This, in turn, had affected the price structure of the economy.

On arrival at the mess, even before we sat down, whisky-sodas were ceremoniously handed to us on a tray. The health of everyone present was toasted. The local commandant had apparently been warned of our arrival and it was his turn to prove that Iberian hospitality, even in the jungles of Africa, was the best. The Americans could not have done better, he insisted.

We continued drinking before, during and after lunch and only stopped well into the afternoon when sleep seemed the only sobering solution. Siestas were obligatory in Cabinda; it was the climate, the commandant explained.

It soon became clear that the Cabinda tropics could have a fairly severe affect on the drinking habits of the average European who spent any length of time along this stretch of tropical West Africa. You never really get used to it, one expatriate at the hotel explained. The result was a neurotic edginess that could sometimes only be stilled by a glass in the hand.

It was probably one of the reasons why many of the old Coasters who came to West Africa would finish a bottle of scotch before lunch. ‘It quickly becomes a way of life—before you realize it’, the major said.

After the passionate, long-legged, smiling black girls of West Africa, liquor was always the worst enemy of the white man while stationed in that stifling heat.

Few of the men at the mess lasted longer than two years before they requested a transfer.