Why Portugal Lost her Wars in Africa

In the late 1960s it was Portugal – after Israel – that proportionate to population had the highest percentage of people in arms in the world. Lisbon showed an annual increase of 111 per cent between the 49,422 that were officially listed in 1961 and the 149,090 documented in 1973.

The question remains: why did Portugal lose its wars in Africa? For more than five centuries, Lisbon maintained the most dominant colonial presence on the continent. Yet, by 1974, she had lost all in a series of bloody military campaigns that lasted half a generation.

The more immediate issues are clear. When her colonial wars began, Portugal was on the lowest rung of poor European nations, with a population a little more than nine million. Yet she had colonial responsibilities that stretched around the globe. Apart from the three metrópole-províncias ultramarinas in Africa, there was Goa in India, Macau on the east coast of China and what was to become East Timor. None of the three Asian dominions were of any size, but each required a presence, both civil and military.

Additionally, the African conflicts were not centralised, such as the wars faced by the French in Algeria or the British in Kenya during the Mau Mau emergency. Rather, Portugal was sucked into a half-a-dozen different rebellions on eight or nine different fronts. One major military campaign in Angola’s north became two when ZIL (Zona de Intervencao Leste) was initiated, first by the MPLA and later by Dr Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA. Several smaller revolutionary groups, each eager for a slice of the pie, operated out of the Congo and though largely ineffectual, they still needed soldiers with guns to counter their advances.

Similarly, there were two fairly large and sophisticated groups fighting for territory in Portuguese Guinea, the PAIGC in the south and based largely in neighbouring Conakry and FLING out of Senegal.

One large guerrilla group was responsible for almost all hostilities in Mozambique, territorially, one of the biggest countries in Africa. And while the war started in the north, it soon moved to regions adjacent to the Zambezi Valley.

None of these uprisings were small fry. Instead they required an army, that with irregular African service units and local militias (including ‘commando’ type units at special rates of pay) and a police force that was quasi military anyway, ended up to close to a quarter million men.

There were naval components in all of them, including a sizeable force on Lake Malawi in a bid to interdict seaborne infiltration from both Tanzania and Zambia. And finally, leading the defensive thrust, the Portuguese Air Force – after South Africa and Egypt – fielded the biggest strike capability on the continent.

The actual numbers of operational aircraft were never constant because there were simply not enough technicians to keep them all airborne. Which meant that if the books showed six or eight Douglas C-47s in Mozambique, there might only be two or three airworthy at any one time. The same with the Fiat G-91 jets.

Lisbon’s helicopter units appeared to be more fortunate, in large part because the Alouette gunships were rugged enough to take a battering from ground fire, unless the guerrillas managed to separate a tail boom or hit a gearbox, which also happened now and again.

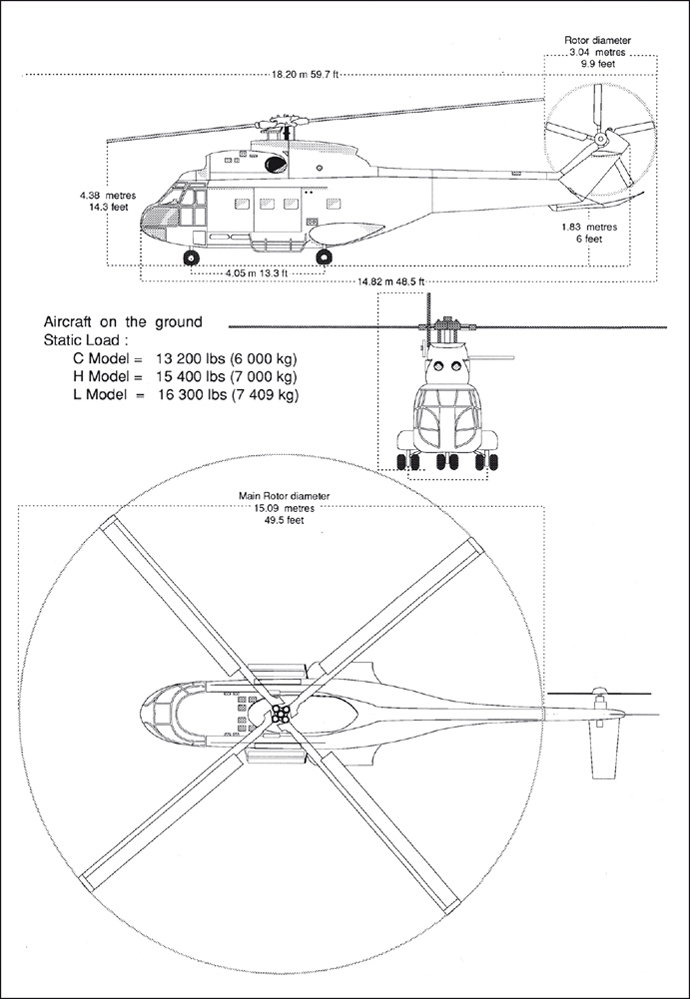

Still, there were massive gaps in the deployment of Lisbon’s troops and fewer helicopters in all three overseas provinces than you are likely to find in any large American city. While the Portuguese Air Force had ordered Aerospatiale Pumas, a dozen of these were destroyed on the ground in a single night after being delivered from France, by a radical anti-war group opposed to Lisbon’s presence in Africa. That meant there were only a handful of government troopers in any of the theatres of African military activity and only two for all of Mozambique.

Cumulatively then, all this military activity spread over an area almost half the size of Western Europe needed manpower, something that became more acute as the conflicts dragged on and one of the reasons why the Portuguese turned increasingly towards using indigenes to assist with the fighting.

More significant, while a trusted member of NATO, Portugal’s assets were embarrassingly sparse when compared to what her adversaries were getting from the Soviet Union and China. In a sense, this was an African version of Vietnam, only Portugal was no America.

Historically, development of the ‘Overseas Provinces’ had always been pitifully slow. The accent had always been on cheap labour, which, in part, meant keeping the populace relatively uneducated. And while the majority spoke Portuguese – as they still do today, a generation after the bloody transition, and there was great emphasis on what was termed the Great Society, there was little real authority vested in the provinces. Anything of importance was invariably referred to the ‘motherland’, the ultimate power, which, in any event, was a dictatorship.

René Pélissier, an academic authority who has written extensively about Portugal’s wars, makes the point that economic exploitation of the workers ‘was often brutal’. He illustrates his thesis by explaining what contributed to the Baixa de Cassange ‘Cotton Revolt’, the least known, yet, as he says, the most comprehensible of all the rebellions of 1960-61. Essentially, he declares, the rebellion was an act of defiance against the system of obligatory cotton cultivation for which Cotonang – a Lisbon headquartered monopolist company – had the concession in the region east of Malange.

Pélissier goes on: ‘Censorship was such that it is not known precisely when and where the revolt started. The causes were numerous: the local population was forced to cultivate cotton, to the exclusion of foodstuffs in certain areas … the 31,652 producers of the Malange district were obliged to sell their whole crop at a price fixed by the government well below that of the world market … moreover, to the east of Malange there was a veritable ‘cottonocracy’ that relegated the rural African to the role of being merely a provider for the company.’

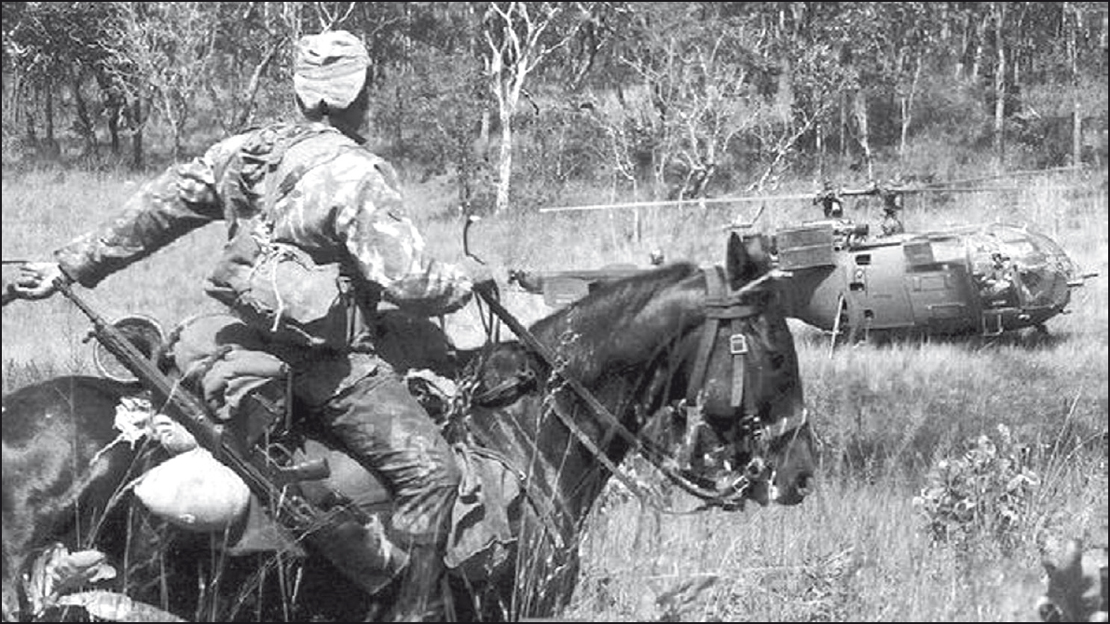

From the very beginning of hostilities in 1961, the nature of conflict in Angola was both tough and demanding on man, machine and on totally inadequate and often outdated equipment. Overnight, this society was obliged to face a threat that would change 500 years of Portuguese colonial rule in Africa. This photo was used on the cover of Brigadier-General W.S. van der Waals’ book Portugal’s War in Angola.

He tells us that the annual income of an indigena family under this regime in 1959-60 was $20 to $30 or roughly two dollars a month, which by any standards, was unconscionable. As he says, ‘this can justifiably be called exploitation; it was, indeed, denounced as such by some members of the Portuguese administration’.

Moreover, the African colonies were subject to the bidding of legions of functionaries who – with the military or the law just outside the door – oversaw everything, from local government, administration of the civil service, education, health, trade, commerce, industry to utilities and the rest.

In theory, Angola being an immensely wealthy region, there should have been an abundance for all its citizens, whatever their colour. In practice, Portugal’s African population were relegated to a level of second class citizenship that would sometimes make conditions in apartheid-ridden South Africa appear conciliatory by comparison. Forced labour was commonplace, so were public beatings.

Rule of government was not only brutal, it was repressive and exploitative. Forced labour was exacted on a massive scale: many of the country’s roads were built with prison labour. The Portuguese secret police, (PIDE, the so-called International Police for the Defence of the State or Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado) – later replaced by the DOS, Direcao Geral de Seguranca – was almost a government in itself. Its methods were often cruel, and in some respects could compare with those of the Nazi SS or Iran’s Sawak during the rule of the Shah.

Additionally, while everybody was supposed to be governed by a single, universal set of laws, there were very different criteria for Portuguese nationals and ethnic Africans.

Blacks could be arrested at the whim of the local Chef do Poste for trivial offences. Not paying the mandatory head tax or perhaps using bad language in the presence of a Portuguese lady could result in a jail term. Similarly, anybody encouraging labour unrest for better wages was charged with sedition and sent to prison. Since the entire country was ruled by decree, any kind of political activity, black or white, was ruled illegal.

Severe laws were imposed by harsh and uncompromising bureaucrats. Often mindlessly brutal, they were rarely made to account for their actions, even when there were lives lost. Coupled to that, black wages in Angola, Mozambique and Portuguese Guinea were among the lowest on the continent.

As might have been expected, living conditions throughout this expansive overseas empire were dismal, for black people especially. Lisbon would always argue that in the long term, it was better for all because nobody starved. Nor did they, but by the end of World War II, this political scenario was also a clear-cut recipe for revolt.

Portugal’s empire came into being directly as a consequence of the successful efforts of Lisbon’s Prince Henry the Navigator to discover a trade route to India.

While other European nations had previously preferred the more ponderous and dangerous overland road to the east, through the Levant and age-old Persia, the Portuguese, to give them their dues, looked at the alternative option. That was by sea, around the Cape.

To take this giant step – which, in its day, was every bit as momentous as man’s first flight to the moon – they needed along the way, a succession of supply stops for fresh victuals and water, which is why they established overseas trading stations in Angola and Mozambique. These eventually expanded and were ultimately settled by Portuguese nationals who, by the time war ended, numbered more than 300,000.

The frontiers of the various African states had been drawn up by all the European countries with interests in the continent around a negotiating table in Berlin towards the end of the 19th century. These included Britain, France, Portugal and Spain, Amsterdam’s colonial interests having long ago been superseded by London.

Putting down roots in Africa –after having first to placate it – was never easy. Tribal leaders were traditionally suspicious of strangers bearing trinkets, and for good reason.

First Portuguese reinforcements sent to Angola after the invasion in a ceremonial march through Luanda. (Photo Manuel Graça)

Africa had always been a ready source for slaves and though East Africa was the first region to be subjected to this pernicious influence that was mainly Arab to start with, the word got quickly around, especially since slaving forays had taken place deep into the interior of a continent that was already being referred to as ‘dark’ by early chroniclers. Consequently there were vigorous attempts by some African leaders to prevent the establishment of a permanent European presence, especially on the periphery of their tribal kingdoms. But the early Portuguese explorers were a resolute lot and they persisted.

Once the first colonists had settled along the coast of Angola and Mozambique and early settlements like Luanda, Bissau and Lobito became towns, black leaders not yet under the ‘protection’ of Lisbon would do what they could to prevent these newcomers from taking more land. Attempts at countering the settler influence went on for centuries, especially in Angola.

Nor were other African colonies immune from rebellion. In Southern Africa there were numerous uprisings among the tribes, first by the Xhosas and their allies and subsequently by the Zulus, insurrections that later spread northwards into Matabeleland and what became known as Rhodesia.

Some tribes sought protection from Queen Victoria. The always-resourceful Sotho people urged British dominion status for their mountain kingdom when they felt that Boers on the move northwards from the Cape were starting to encroach on traditional land, which is how Basutoland, afterwards Lesotho, came into being.

It was a time for rebellion in Africa; in the Gold Coast, in Benin, Nigeria, in some of the French colonies and against newly arrived North Europeans in German South West Africa (Namibia today) and in the Kamerun.

The bloodiest uprisings might well have been the notorious maji maji rebellion in Tanganyika which went on for more than a year.

As the history books recount, the Nyamwezi Chief Isike – from the central Rift Valley region around Tabora – fought a grim rearguard action against the Kaiser’s soldiers that started in 1891. Rather than surrender, he blew himself up in the armoury of his fort in January 1893, which, in turn, paved the way for the maji maji war that followed a dozen years later.

For five centuries, there were any number of uprisings by locals in the Portuguese territories and all failed. Except for the last, which was sparked in 1961 by a murderous uprising among Bakongo people of Northern Angola and the Congo. Thousands died in the violence that followed, including 2,000 Europeans.

According to René Pélissier, the events of 1961 were to shake the Portuguese out of their lethargy and dreams. It also awakened unfulfilled hopes in the Africans, and, at the same time, brought down on a whole racial group – the Bakongo, and on a good proportion of their neighbours, the Mbundu, as well as on other assimilado cadres – the horrors of war and repression.

For the Portuguese, says Pélissier, it marked the end of colonial tranquillity; for Africans, the beginning of an ordeal. For all it was the year of terror.

But he warns, it is useful, first, to expose certain errors. ‘The Portuguese were not taken totally unawares by the events themselves. What caught them off guard was the racial massacre that followed in the north. It was not the rebellion, but its intensity, its suddenness and its bestiality, which nearly brought about their loss of Angola.

The settlers were expecting trouble, as is shown by their arming: in 1959, Angola imported 156 tons of arms and ammunition; in 1960, 953 tons (six times as much); while, in 1961, this dropped to 424 tons and, in 1962, to 145 tons. It was certainly not to hunt elephants but to resist the Africans if they were to rebel that the Portuguese stocked their arsenals.

In spite of the threat from within and without, Angola in 1960 was, militarily speaking, a no-man’s-land. Even allowing for reinforcements (denied by Portuguese sources), it can be estimated that on the Portuguese side there were only 15,000 to 20,000 whites, mesticos and Africans in the army or para-military organisations: a derisory force to hold a country that might spread into simultaneous, nation-wide revolt.

Funeral of the seven policemen who were killed in MPLA’s ill-fated Luanda uprising of 4 February 1961. The white community brutally turned on African people in the city and many innocents were murdered. The event was a dramatic precursor of the civil war that followed. (Photo Manuel Graça)

He concludes with the comment that it must not be forgotten that:

if Angola failed to achieve independence by armed revolt in 1961, it was because only a small minority if its peoples and elite dared to demonstrate anti-Portuguese feelings.

Whether through fear, lack of interest, ignorance, incompetence or loyalty, the peoples to the south of the Cuanza hardly budged; if only the nationalist chiefs had found there as favourable a terrain as they did in the north, it is virtually certain that the Portuguese would have been swept from Angola, or at the least confined to their strongholds along the coast.

With the benefit of hindsight, it is astonishing that of all the European colonial powers, Portugal’s grip on its African territories over the centuries – ruthless, intractable and totally impervious to change as it was – proved to be the most durable. As old timers in Luanda and Lourenco Marques would mutter, it wasn’t perfect, but after a fashion, things seemed to work.

They’d contend that after all, this was Africa. Pressed to elaborate, as I often did in some of the little restaurants in those two cities, they’d confide that the real problem lay with the indigenes. One and all they’d argue, the locals knew no better. There would be no mention of the impact of white rule on African health, welfare and dirt-cheap workforces, and that African lives were stunted by the requirements of capitalist enterprise.

Early Portuguese Army bush operations in the jungles north of Luanda. (Author’s collection)

In some ways it was a very different approach to how other European administrators conducted their affairs. Both London and Paris made serious efforts to improve their understanding of Africa and frame their policies accordingly. In Nigeria, the British went on to institute Indirect Rule, largely to avoid tampering with historical, religious-based systems that had been secure for centuries.

They’d also learn the local languages, which was how those white Kenyans who had learnt Kikuyu, eventually managed to counter most of the advances made by the Mau Mau.

To many of those involved in countries like Northern and Southern Rhodesia (Zambia and Zimbabwe today), Nigeria, Uganda, Sierra Leone and elsewhere, co-operation with indigenous rulers ultimately proved the best way to retain control at minimum human and material cost.

Lisbon did things differently. With time, Portugal’s three African colonies – on paper, at least – became what politicians in the Metropolis would like to call ‘one big, happy, friendly family’.

It was a splendid idea, except that the colonies were African, often proudly so. The majority of people there had tribal origins that were impossible to ignore, something that was often lost on those in charge. We are also aware that the system of government imposed on these societies, were insensitive. While never mindlessly as brutal as the excesses imposed on the people in the neighbouring Belgian Congo – and which Joseph Conrad masterfully captured in his denunciation of colonialism in his Heart of Darkness –the Portuguese, though not racists per se, could sometimes be cruel to people of colour.

Being Africa, things also tended to move very slowly. Inexorably, the tribal system tended to generate its own laws of cause and effect and these people have long memories.

The Cambridge History of Africa tells us that ‘on the eve of the Second World War, the Pax Euopeae was firmly established in Africa.1 At one level it was a seemingly tenuous peace, dependent on a handful of European administrators ruling over vast and populous areas with only a handful of African soldiers or para-military police at their disposal.

Nigeria, for example, had only 4 000 soldiers and 4 000 police in 1930, of whom all but 75 in each force were black.

Just how thin on the ground the European administrators were, can be seen from the fact that in this corner of British West Africa in the late 1930s, the number of administrators for a population estimated at 20 million was only 386: a ratio of 1: 54 000. And that included those in the secretariat.

In the Belgian Congo the ratio was 1: 38 400 and in French West Africa 1: 27 500. It should also not be forgotten, that in parts of the European empire, the colonial imprint was still very light. Many Africans had never personally seen a white man, while in Mozambique parts of the territory were not even administered by the government but by concession companies.

More salient, those same ‘concession companies’ were motivated solely by profit.

Despite all these disparities, it took a while but the master-servant labour system in Portuguese Africa became entrenched. Those who knew no better accepted social dominance as the norm. Also, life in the Overseas Provinces was unquestionably mixed, to the point that relations between the colonisers and the colonized gave rise to the old maxim: God made man white and God made man black, but the Portuguese made the mulatto.

Then, quite suddenly, arrived the age of Uhuru – the Swahili watchword that shook East Africa ‘as in a whirlwind’. To the majority, it signified freedom.

‘Freedom of the masses’ Kenyan President Jomo Mzee Kenyatta would proclaim with verve while he waved about his ubiquitous oxtail that also served as a fly swatter. Almost overnight a novel and thoroughly radical concept was being espoused from one end of Africa to the other, and as my old friend Chris Munnion commented early on, it didn’t take any of us long to realise that African politics were in an state of flux, alarmingly so.

The ‘winds of change’ in Africa became a part of that equation soon afterwards and it was not too long before a plethora of independent states came into being: countries like Gambia, Nigeria, Gabon, the Cameroons, Burundi, Chad, Sierra Leone and the rest. But not one under Portuguese rule. Of all the European colonial powers, the Portuguese proved the most intransigent. Sharing power, simply put, was anathema.

There were few people in the Metropolis who were not of the mind that no matter what, the nation would survive without any kind of political change. What was happening in parts of West, Central and Southern Africa would be referred to in the state-controlled press as a ‘passing phase’. Lisbon’s African possessions were part of a culture and a great historical tradition was the theme. For all its faults, ran the concept, Portugal and its Overseas Provinces had even eclipsed Iberian domination of the New World.

Indeed, Angola at that time was regarded by some as the ‘future Brazil of Africa’.

What Lisbon had not initially factored into the colonial equation was communications. What was going on elsewhere in Africa, could obviously not fail to have an impact on the peoples of Angola and Mozambique. How else when Lisbon suddenly had to deal with a number of former British and French colonies now in control of their own affairs, several their immediate neighbours?

These included Senegal, Malawi, Congo-Brazza as well as quite a few, including Guinea, Tanzania and Zambia that were passionately opposed to any kind of Portuguese colonial presence on the continent. All three countries were later to wage hostilities against Lisbon. They also permitted revolutionary groups to operate from their soil.

Even this, some Portuguese colonists believed they could deal with. And they probably could have, had those belligerent neighbours acted on their own. But this was the time of the Cold War and both Moscow and Beijing believed that ultimately, they had good prospects in Africa.

One of the architects of the African revolution that eventually changed the modern face of Southern Africa from white to black was a modest African academic who was respectfully referred to by just about everybody with whom he came into contact as Mwalimu, the Swahili word for teacher.

Julius Nyerere, a graduate of Kampala’s one-time prestigious Makerere University, got a scholarship to attend the University of Edinburgh in 1949, a remarkable distinction at the time because he was the first Tanzanian to study at a British university.

Much to the chagrin of the British colonial authorities, Nyerere was already very much of a political factor in the old Tanganyika by the time the ‘Revolutionary 1960s’ arrived. He was abrasive towards the establishment, espoused a new form of African socialism which he called Ujaama and had the kind of chutzpah that could sway large crowds. After numerous confrontations with London’s representatives in Dar es Salaam, he led his country to independence to become first prime minister, and later President of the Republic of Tanzania.

Nyerere was one of many post-war African heads of state with strong academic and emotional links to the radical British Left. Others were Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Milton Obote of Uganda, and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia. It is significant that all four chose the Socialist path, usually through the good offices of the London School of Economics.

An arms cache recovered from a guerrilla position that had been overrun by government forces. (Author’s photo)

Political sentiments apart, Nyerere ended up embracing every revolutionary who arrived at his door, including a good few from Angola and Mozambique.

Within a year a dozen Southern African revolutionary movements from Rhodesia, South West Africa (Namibia today) and even a few that were not yet independent like Nyasaland and Kenya, had set up shop along Liberation Row in Dar es Salaam. The ultimate oxymoron, Dar es Salaam, in Arabic, means ‘harbour of peace’, but Tanzania now fostered armed revolution.

Julius Nyerere made no bones about wishing to see an end to white rule in Africa. He created an entire political and economic system to that end, first by supporting FRELIMO – the Portuguese liberation movement in their war against the Portuguese in Mozambique and, shortly afterwards, Angolan liberation movements. SWAPO, the South West African (Namibian) revolutionary movement and the ANC’s Umkhonto We Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) soon followed.2

Much of the military hardware needed by these radical groups that still had some way to go before they became fully-fledged guerrilla armies were landed at Dar es Salaam harbour. Customarily, this matériel was moved first by road and then on the backs of human packhorses, often hundreds of kilometers into the interior. A Soviet TM-46 antitank mine, for instance, which weighs about 12 kgs, might have been hauled a thousand kilometres overland by a minor army of porters by the time it was placed in a hole in the ground in Mozambique to await the next convoy out of Tete.

With SWAPO, fighting its own war on the far side of the African continent, logistical problems would often mean journeys that might last months. Weapons would sometimes cross several frontiers, including those of Zambia and, in later stages, Mobutu’s Congo.

It was not long before South African revolutionaries established a secure base for their leaders in the Tanzanian capital. Larger groups of political malcontents that had left South Africa, usually on foot, were housed in camps in the interior

With time, a revolutionary culture of its own evolved in Tanzania, together with a fairly distinct terminology. Tanzania resolutely preferred to call itself a ‘Frontline State’ even though the distance between Pretoria and Dar es Salaam is greater than between London and Athens. Zambia embraced the concept as well, but it was more appropriate because it bordered on Rhodesia, then in a state of war and at the receiving end of crossborder raids launched by Rhodesian security forces.

Ultimately these forerunners were joined by Mobutu Seso Seko’s Zaire – as well as Congo (Brazzaville) to its immediate north with territorial interests in the oil-rich enclave of Cabinda.

While all this was taking place, there was truck between East Africa and the two most prominent revolutionary states on the West Coast, Ghana under Nkrumah and Sékou Touré’s Republic of Guinea – not to be confused with today’s Equatorial Guinea (formerly Spanish Guinea) or Guiné-Bissau (Portuguese Guinea).

Irrespective of nomenclature, the Tanzanian connection was one of several major issues faced by Lisbon as these expanded colonial conflicts gathered momentum.

Looking back, we’re now aware that Portugal’s three military insurrections in Africa resulted in a powerful groundswell of anti-colonial hostility in Portugal itself – as well as elsewhere in Europe and North America, especially among many of Lisbon’s NATO allies. While Lisbon always made much about its historic and ‘civilizing mission’ in Africa, much of that was dismissed as the cynical propaganda of a tottering dictatorship.

As the historian and political commentator Kenneth Maxwell wrote: ‘Portugal was the last European power in Africa to cling tenaciously to the panoply of formal dominion and this was no accident. For a long time Portugal very successfully disguised the nature of her presence behind a skilful amalgam of historic mythmaking, claims of multiracialism and good public relations.’

The reality, says Maxwell, was something very different. ‘Economic weakness at home made intransigence in Africa inevitable. It was precisely through the exercise of[sovereignty] that Portugal was able to obtain any advantages at all from its civilizing mission. And these advantages were very considerable: cheap raw materials, large earnings from invisibles, the transfer of export earnings, gold and diamonds and protected markets for her wines and cotton textiles.’

Portuguese Air Force helicopter gunships and troopers at an unknown location. (Author’s collection)

Vietnam meanwhile, provided Europe and America with a fertile anti-war lobby which, when circumstances permitted, was conveniently switched to Africa. Not only Portuguese Africa became targets, but Rhodesia and South Africa as well.

This approach was adopted – though much less forcefully – by the educated classes in Portugal itself. While popular stereotypes tended to depict Portugal as a stagnant backwater for almost three centuries, students, professional people, academics, the military, government officials and politicians became increasingly sensitive to the opprobrium that resulted from the reactionary policies of the Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar, who suffered a stroke in 1968.

Optimists on both sides of the Atlantic had hoped that under Marcello Caetano, his successor, the country would enter a more liberal phase. While some of the faces changed, the political infrastructure did not, though to be fair, much was done to bring education in line with the Metropolis. For instance, two major universities were established in the 1960s in Angola and Mozambique – the Universidade de Luanda and the Universidade de Lourenco Marques – and both offered a range of degrees from engineering to medicine.

This is all the more notable since there were then only four public universities in all of Portugal, of which two were in Lisbon.

Multiculturalism gradually took root, helped to some extent by the acceptance of the assimilado program which actually encouraged Africans to accept Western values in preference to tribal ones. Here, sport was a touchstone, with many Africans encouraged to vie for top international slots. Among this tiny band of sportspeople was the footballer Eusebio who was embraced by soccer players the world over.

The Brazilian political commentator Marcio Alves wrote: ‘To hold on to the Empire was fundamental for Portuguese fascism. Economically, the African territories – and especially rich Angola – were so important to Portuguese capitalism that Caetano took over from Salazar on the condition that they would be defended.’

Part of the trouble was that in Portugal’s African possessions, no political solution to the problem was either found or sought. If anybody stepped out of line, the only answer was the big stick … or the gun. These people had centuries of reasonably successful African rule behind them and despite the rumblings, things continued very much as in the past.

Matters were exacerbated during later stages of this African conflict by an almost total break in communications in some areas between the security police and the Portuguese defence forces. There were several cases in Tete and Nampula where liberal Portuguese officers informed FRELIMO sympathisers of future movements by PIDE officers into the interior. They knew that such information would be passed on to the revolutionaries and made good use of.

For all this ‘dissention within the ranks’ PIDE had a good measure of the enemies they were up against, in all three territories. I know from practical experience that they got a lot of help from South Africa, which hosted an expatriate Portuguese community of about half a million, many of them former dissidents from the colonies.

Within the war zones, PIDE worked to a complex set of rules that involved thousands of informants that sometimes stretched all the way to rebel command headquarters in Dar es Salaam, Kinshasa, Conakry and Dakar. It was an expensive process, but it worked, as money always does in a corrupt Africa.

Much more intelligence was derived from good old fashioned sleuthing on the ground, coupled to information brought in from patrols, cross-border travellers, captives, documents taken during or after contacts as well as air and naval reconnaissance.

As John Cann tells us in his book, ‘the Portuguese Army realized this critical need for effective intelligence and proceeded to build a productive network that helped its forces exploit weaknesses in the enemy.’ He devotes a chapter that addresses the problems encountered with these operations in the field in selected areas and follows the solutions adopted, comparing and contrasting them to the experiences of other countries with contemporaneous counterinsurgency operations.

‘These several adaptations were uniquely Portuguese and in keeping with the subdued and cost-conscious strategy,’ Cann tells us.3

While conditions in the field in Mozambique remained uncertain until the coup, things were a lot different in Angola which had good resources backed by a settler community that numbered more than 300,000 and had been there for centuries. These people knew no other place but Angola and were prepared to fight for it.

Not so in Portuguese Guinea, where no real advance was possible for its 3,000 white settlers because of the forbidding nature of the country: most of that country was pestilential swamp where the mosquitoes and bad water got you if the guerrillas didn’t.

The traditional and the modern: horses were still used extensively in certain spheres in this ongoing guerrilla struggle. (Author’s collection)

There was also little development, economic or otherwise in Portugal itself, with the result that by the time war ended, it was rated the second poorest country in Europe after Albania.

A great deal of money was squandered in Lisbon’s African war efforts. At one point the government voted almost half the entire budget to the military, which, for many years during the earlier period was roughly what Israel spent on keeping its society secure. But then Lisbon did not have Uncle Sam underwriting its military tab.4

Yet, there are still some who maintain that although Portugal was all but destitute when the war ended, it was not economic policies that caused the collapse of its authority in Africa because it was just as poor when the insurrection started. Their argument was that the dictator Salazar was the real disaster. He had been trained as an economist, and in that he excelled. The problem was that he treated the coffers of the nation as his own, and in so doing, acted like the proverbial miser.

David Abshire and Michael Samuels in their book Portuguese Africa – A Handbook (Pall Mall Press, London, 1969) maintain that during the wars, the Portuguese were able to maintain their gold and foreign reserves at a fixed ratio of between 56 and 57 percent of sight responsibilities. In spite of increased expenditure on defence and the need for external borrowing, Salazar actually managed to increase Lisbon’s reserves of gold and foreign exchange during the war years. Herein lay an example for South Africa, soon to be labouring under similar pressures, as the history books tell us.

The bottom line here is that as the wars in Africa progressed, the bean counters in the metrópole had absolutely no alternative but to cut the coat according to Portugal’s tattered cloth.

It was politics, ultimately, that dealt the death blow to any aspirations the Portuguese might have had of holding on to their African possessions.

The vision among the country’s ageing leaders to improve the political situation either at home or abroad, or to strengthen the military equation was blinkered. If ever there was an example of political leadership having atrophied while in power, it could be viewed in Portugal, especially since Salazar had been in power since 1933. When Caetano succeeded in 1968, the same people who supported Salazar ended up in the Caetano cabinet. There was therefore no change in form or content.

Of course, Africa was prominent in the minds of both Salazar and Caetano; and, curiously, South Africa became the focus of attention on several occasions. Salazar, it emerged after he had died, was obsessed with the threat of a Mozambique Unilateral Declaration of Independence or UDI, much like Rhodesia had declared in 1964. This later became a mania; Salazar believed that there were people in Mozambique plotting with the South Africans to overthrow the government in Lourenco Marques.

Matters weren’t helped by the many South Africans who wished to invest in the Mozambican economy. Although it was permitted at first on a small scale, it was only in 1966 that any considerable foreign investment was allowed into Angola and Mozambique. By then it was too late.

Because of his UDI fears, Salazar permitted little economic development in his Portuguese possessions.

Angola was the one region where the possibilities of independence from Portugal had been mooted for decades. Had the war not arrived, there is little doubt that Angola would have followed Rhodesia’s example.

Douglas Porch, in his book The Portuguese Armed Forces and the Revolution (Croom Helm, London, 1977) mentions an air force colonel in Angola who said:

In 1965, most of us already thought that Angola should become an independent and racially mixed country like Brazil. We saw that we could not win in the colonies. It was impossible to continue. Freedom had to come gradually because the people were not prepared for it. The military would be very useful in preparing the political solution. It was a task which we could not do in two months, but in six or seven years. We had to prepare the government and the local governments.

The army had to maintain independence, build up the armed forces and so on …

In direct contrast, the wisdom of the day in Lisbon was twofold: first, you did not negotiate with the enemy, and especially not if they were in a position of strength, which they were for much of the time, in Guinea and, afterwards, in Mozambique where the Portuguese was stuck with inferior leadership and a terrain that was far too big to control effectively with so few troops on the ground.

‘Lisbon – 13999 kms’ tells its own story! (Author’s photo)

It is more than 2,000 kilometres long and almost twice the size of California; interestingly, it is roughly the same shape too.

For all that, the Portuguese Army by 1973 had about 70,000 men on the ground in Mozambique, in a country where there was a single, reasonably maintained road that stretched from north to south. Most of the rest weren’t tarred, which perfectly suited FRELIMO minelayers.

The real downfall of Portuguese interests in Africa ultimately lay with the armed forces. To start with there was great dissatisfaction among members of the Portuguese military over service in Africa.

A two-year period of service in Africa was usually followed by six months at home and then another two years in the provinces. That practice had a crippling effect on morale in the war zones. There was also bad feeling between regular soldiers and conscripts, particularly within the junior and middle ranks of commissioned officers.

The MFA or Armed Forces Movement which eventually organised the coup d’état of April 1974 recognised that no political development was taking place either in the military or in the African territories. General de Spínola actually said as much in his book Portugal and the Future, but more of that later.

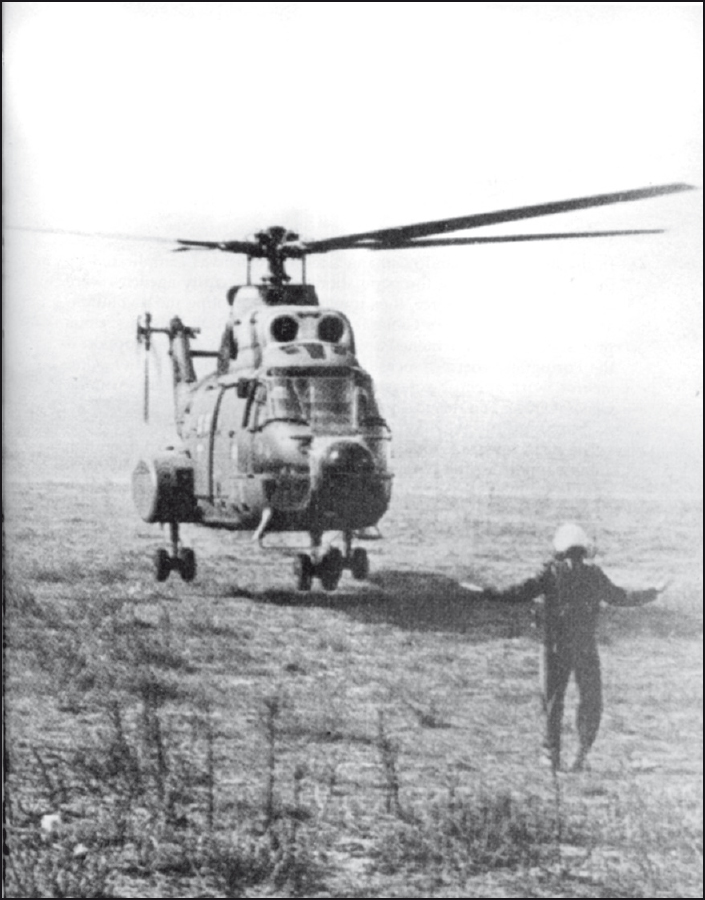

Puma transport helicopter – French built and ideally suited for primitive African conditions – is ‘talked down’ at a forward Angolan base. (Author’s collection)

There were also powerful radical elements at work within the regular army. Many officers were known to be communist and actually espoused the doctrine, yet they were allowed to continue to serve their country as dutiful patriots, in part because some of their senior officers were of similar minds.

Brigadier General W. (Kaas) van der Waals, the last South African military attaché in Luanda prior to the Portuguese leaving Africa has his own views on developments:5

The military coup in Portugal took the world, including South Africa, by surprise. To well-informed observers, however, the news was not completely unexpected. One of the general officers prominent after the coup as a member of the military junta was General Francisco da Costa Gomes. He was destined to become Portugal’s second post-coup president and it was during his reign that Angola would slide into civil war in 1975. Eventually it would be left to its own fate as Portugal abandoned its responsibilities on November 11, 1975.

I worked closely with Costa Gomes after he became commander-in-chief of the armed forces in Angola in May 1970 and I found him soft-spoken, shy and a regular visitor to his troops in the field. Strange to relate, in the light of subsequent events, it was he who changed significantly the military situation in Angola. He arrived at a critical time and when he left two years later the military crisis had dissipated to such an extent that optimists believed the war had been won. However, there were doubts in certain quarters concerning his sincerity and loyalty.

Shortly after Costa Gomes’ appointment, a senior Portuguese officer remarked to the author that the new commander-in-chief was a communist who had been sent to Angola to prepare the ground for a handover. To some, his military successes dispelled the doubts. But having done some research of my own, I discovered that after the outbreak of hostilities in Angola in 1961, Costa Gomes had been involved in an abortive coup against the Salazar government. So doubts persisted.

Returning from Namibia a few days after the coup in April 1974, I was in contact with military intelligence in Pretoria. Two years earlier I had submitted a report forecasting the possibility of decolonisation in Angola. At the time, it was accorded little attention, but now all that material was analysed afresh.

In particular, note was taken of a letter written in March 1972 by Costa Gomes’ predecessor, General Almeida Viana to a member of the Angolan Legislative Council in which he referred to a conspiracy in Portugal, after which Angola would be left to the “vicissitudes of the times”.

Could the seemingly spontaneous events of the spring of 1974 have been planned two years before? There is no hard evidence to support this contention, but it is known that conservative elements of Portuguese society, including the top structure of the armed forces were very much concerned at that time about Caetano’s liberalisation of colonial policy.

He was even called Portugal’s de Gaulle. Something was indeed brewing.

Dimensions of Aérospatiale Puma SA 330. (Graphics by Dr Richard Wood)

Significantly, some Portuguese officers (as with some South Africans of similar persuasion) tended to equate their military efforts in Africa with the French in Algeria. Porch draws this analogy by stating that in Portugal, as in France, the circumstances for the military coup were provided by a long and exhausting colonial war.

There were crucial differences between the two countries. Many French soldiers believed that they were almost within striking distance of victory. They reacted against what they believed to be a betrayal by de Gaulle. Portuguese officers in contrast, felt that the country was locked in a pointless struggle to maintain a burdensome empire. Also, Portugal’s colonial wars sapped the country’s strength, made her appear ridiculous in the eyes of the world, and ruined the army by flooding it with half-trained conscripts whom the government attempted to promote over the heads of long-serving regulars.

As Porch maintains, the latent resentment which gradually built up to scalding point in the officer corps, was a combination of bruised national pride and wounded professional vanity, an explosive mixture of sentiments which the Portuguese military establishment shared with revolutionary soldiers in Egypt and other Third World countries.

A typical Angolan aldeamentos. During the Malayan Emergency these enforced settlements were called ‘Protected Villages’, the idea being to isolate the civilian population from guerrilla influence. It worked well enough if security was tight (as it was in the Far East). In regions controlled by the Portuguese, security was never adequately enforced, which nullified both the effort and the expense. (Author’s collection)

The Portuguese experience proves that the increasing professionalism of the armed forces can hasten its entry into the political arena rather than discourage it, as American historian Samuel Huntington has argued.

Professional discontent creates shop floor militancy and the coup substitutes for the strike.

In retrospect, it is astonishing that Portugal never considered transferring families to the African colonies for these extended periods of anything up to five years. Their principal argument against such a step was the UDI bogey: a real fear that too many metropolitan Portuguese would be sent to the African colonies and then begin to think for themselves, as the Rhodesians had done.

Occasionally one found a member of a family, usually that of an officer, comfortably off and able to afford such a luxury, in one of the African capitals.

While I covered the war in Portuguese Guinea in 1971, the beautiful new wife of a young Alfares shared our table when her husband was in the bush. She’d been staying at the hotel for almost a year and was not dismayed by the prospect of a second year in Bissau, a dreadful tropical backwater.

The differences to what she was used to back home were immense. Unlike Luanda or Lourenco Marques, the enclave was almost totally black and, to her, quite alien. There were almost none of the pavement cafes that we knew in Mozambique; no good beaches, no recreational parks. All that lay at the edge of Bissau was the jungle and the war. The hotel which we all shared, the Grande, was a misnomer: it was a grim, rambling, stuccoed doss-house that was older than the century with no air-conditioning. Only the bar showed any animation; it was raucous by midday.

Then there was the question of money. As any soldier will tell you, he can do without women, but not his beer.

Four years in Africa was not eased by the fact that a Portuguese soldier’s pay was derisory. A brigadier serving in Africa in 1971 got about US $250 a month. A private got perhaps US $ 40 and perks were few. Home leave outside the period of service was almost unheard of; and anyway, who could afford a ticket back to the Metropolis? Even if he travelled steerage on one of the many Portuguese liners serving the African colonies, time was against him since they stopped just about everywhere on both outward and homeward legs.

The pay structure was pitiful, almost Third World by comparison. No doubt this factor ultimately played a role in switching the allegiance of the armed forces.

Pay Scales in Portuguese escudos —January 1974 (with an exchange rate of about a rand, or roughly one American dollar equal to $40, where $ = Portuguese escudos):

General (4-Stars) and Admiral |

$18,900 |

General and Vice Admiral |

$17,200 |

Brigadier and Rear Admiral |

$15,500 |

Colonel and Navy Captain |

$13,900 |

Lt-Col and Navy Commander |

$12,300 |

Major and Navy Lt.-Commander |

$11,400 |

Captain and Navy Lieutenant |

$10,400 |

Army Lieutenant and Navy Lieutenant j.g. |

$7,300 |

Lieutenants and Guardo-Marinha |

$6,000 |

2nd Lieutenant or Navy Ensign. |

$4,700 |

Sergeant-Major (Adjutant) |

$5,700 |

First Sergeant |

$5,400 |

Second Sergeant |

$5,000 |

Sub-Sergeant |

$4,700 |

Corporal |

$4,700 |

First Corporal |

$3,400 |

Second Corporal |

$3,300 |

By way of comparison, Porch observes that not long after the war started, a full colonel of an infantry regiment stationed in Portugal earned 10,200 escudos a month which would have been something like $250. A British colonel earned about double that, while a French colonel took home about 5 or 6 per cent less than his British counterpart.

Physical conditions too, especially out at the ‘sharp end’, were abominable. Military camps at such remote corners of the empire as N’Riquinha, Nambuangongo and Cabinda in Angola, and Zumbo, Tete, Zobue and Guro in Mozambique, or any one of the postings in Portuguese Guinea were invariably quite barbarous and unhealthy.

In some places the tribesmen actually lived under better conditions than their ‘protectors’, especially where they were herded together in their Malayan-style protected camps or Aldeamentos.

At the end of it all, there are those who maintain that for all Lisbon’s problems and makeshift means to fix them, it was Portuguese Guinea that was the main cause of the decay that set in among the Portuguese armed forces. By 1972 it had become apparent to even the most sanguine supporter of Portuguese rule in Africa that the war in this grim jungle and swamp terrain on the west coast of Africa could not be won.

There were several reasons; all were pertinent. The terrain made any proper military operations not only cumbersome but often impossible. The navy was as much involved as the army, but both forces had different ideas about fighting a hidden, well-armed and aggressive enemy that was given all the arms and equipment it needed by its radical friends. To compound matters, the two arms rarely shared the kind of intelligence that might have made a difference in the outcome of scrapes in the bush with the rebels.

Moreover, unlike Angola and Mozambique, the country was almost totally undeveloped. There were almost no industries and hardly any exports.

The first question that most conscripts asked on arriving in Portuguese Guinea was: ‘Why are we here?’

When I tackled one young lieutenant in a camp near Cacheu in the north of the country, he retorted with comments like ‘what’s all this bullshit about? This is neither my home nor my country.’

Portuguese Guinea had none of the towns, industries, diamonds, coffee or hardwoods of Angola; or any of the pleasant amenities of Mozambique. Yet, by 1961 the African colonies had actually begun to make a small profit for the metropolis. But not Portuguese Guinea.

Furthermore, the country was miniscule, barely bigger than Lesotho, and its borders constricting. Portuguese garrisons were regularly shelled or rocketed from neighbouring territories. And while the lack of space and ability to manoeuvre should have worked against the guerrilla, it also militated against the Portuguese.

There was another problem. It should have been relatively easy for the Portuguese to withdraw from Guinea. But, as apologists in Lisbon pointed out, that would have been impossible without abandoning the other two; the Domino Principle would take effect at once, they warned at a time when domino theories were being bandied about in South East Asia.

The most active Portuguese commanders constantly advocated cross-border raids to prevent attacks by insurgents who found safe havens in neighbouring territories. Permission was always refused.

As a result of being unable to take retaliatory action, largely from fear of foreign disapproval, neighbouring states continued to provide succour to a variety of insurgent movements.

What Portugal feared most was further isolation. Criticism from abroad had already begun to hurt.

Curiously, in spite of all these shortcomings, Portugal’s defence establishment eventually evolved an excellent counter-insurgency doctrine.

This was begun in 1962, soon after the first outbreaks ofviolence in Angola. It eventually comprised four huge volumes and drew on the experiences of every modern conflict: the Americans and French in Vietnam, Britain in Malaya, Borneo, Cyprus and Aden, France in Algeria, and such obscure conflicts as that of the Huk uprising in the Philippines; as well as others.

The entire principle was brilliantly applied by the staff corps, but they lacked the attitude and experience of some of the officers who had already seen a useful amount of active service. Thus, while the planning was thorough and technically competent, the execution was inferior.

On more than one occasion I heard South African officers, who had come into contact with the Portuguese forces, discussing the excellent theory, and how some very well constructed operational plans had fallen flat because the work on the ground was so poor.

Then, as the war progressed – and apart from casualties, which were not severe – more and more young men failed to answer the cause. The strain on Portuguese manpower in 1967 caused the age of conscription to be lowered to 18. That was followed by the conscript service term to be extended from two to four years by the addition of two years’ compulsory service overseas. However, not all those called up actually served.

As opposition to the wars in Portugal itself grew, so avoidance of the call-up increased. It is estimated that something like 110,000 Portuguese failed to report for military service between 1961 and 1974, either through deliberate avoidance or absence abroad, since over a million Portuguese were emigrant workers by 1974. The joke in Europe was that almost every other waiter in some Parisian and German restaurants originally came from Portugal: almost all had dodged conscription

In the last call-up, before the April 1974 putsch, less than half of those who had been sent their papers reported for duty. Consequently, as the defence establishment grew, the universities were called upon to provide many more of the junior officers needed to fight.

These were enlightened young people, who had observed the dictatorship at first hand. They were aware of what President Caetano’s legacy had done, and what it was still doing to their homeland.

Few were under any illusions that they would be involved in what the Americans like to call ‘a just war’. Nor were they made overly welcome by regular officers of the army and air force; veterans who’d spent years in uniform struggling up the slow ladder of promotion. In the Portuguese Armed Forces any kind of vertical movement could be very slow indeed and often depended as much on family contacts as ability. A man rarely reached the rank of colonel before he’d reached the ripe old age of 50.

It was these same professionals who deeply resented the newly commissioned lieutenants and captains who had usurped their positions and much distrust resulted between the two groups.

Ultimately, it was these liberal officers and their undermining of the Portuguese war effort – both at home and abroad – that led to the formation of the Armed Forces Movement, followed by the 1974 coup d’état.

Almost immediately, the Portuguese forces in Africa laid down their weapons and stopped fighting, Within a year, Lisbon had departed Africa for the last time, almost a million of its citizens scurrying back to Europe, many having lost everything.

It was a truly ignominious ending of a magnificent though flawed five century colonial tradition, but, on reflection four decades later, there was really no alternative.

Portugal’s had matched wits and strength with the surrogate forces of the Soviet Union and lost.