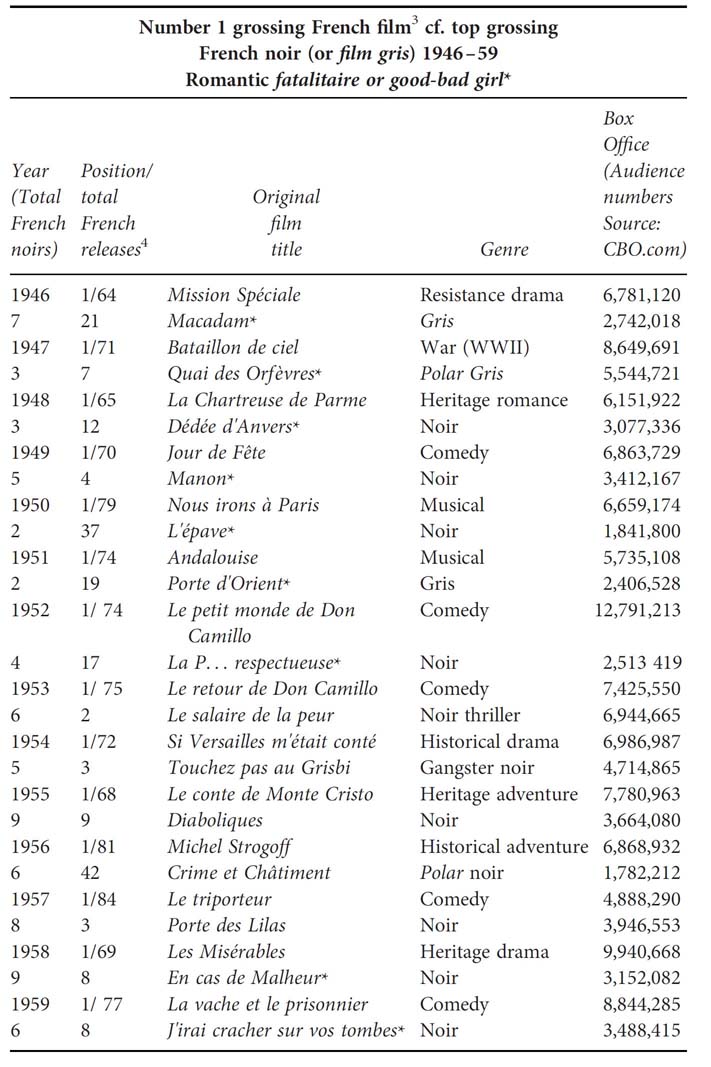

Table C.1 The comparative popularity of Classic French noir34

Classic French Noir: The Dark Side Of

‘Quality’ Cinema (1946–59)

During the postwar period 1946–59, despite huge competition from the USA,1 French cinema was overwhelmingly popular, constituting the form of popular entertainment par excellence: over 75 per cent of French produced films attracted audiences of more than a million (for a total population base of 40–45 million) as against barely 6 per cent of films from 2010–6 (for a total population of around 66 million). In order to compete against Hollywood, the French cinema industry invested in culturally specific, technically sophisticated, high-production value ‘quality’2 productions, often co-produced with European partners. The most popular genres were light comedies, musicals, lavish scale historical swashbucklers and heritage dramas that drew on France's prestigious literary past. In contrast, le réalisme noir and dark polars represented the dark side of French quality cinema, in which postwar cynicism, romantic despair and crises of masculinity seep through.

While classic noirs often attracted smaller audiences than conventional crime dramas, adventure thrillers and comic parody noirs offering lighter entertainment and the emotional reassurance of positive closure, they were nonetheless an integral part of the popular mainstream. The most successful featured in the top ten French releases (out of an annual production of 64–84 films including co-productions) for eight out of fourteen years. From 1955–59, even though critics were growing increasingly weary of a ‘genre’ many felt had become formulaic and repetitive, films noirs remained popular with audiences. (See Table C.1)

Gender and power in classic French noir

Leading commentators on classic French cinema Noel Burch and Geneviève Sellier frequently cited over the course of this book, make strong claims for its prevailing misogyny, as evidenced by ‘a plethora of evil women’. According to their research, 25 per cent of French films made between 1945 and 1955 (across genres) feature the ‘sale garce or evil bitch, who uses her powers of seduction to exploit, enslave and/or destroy men’.5 A key question for the present study has been: is French noir misogynous? Given that noir addresses the dark side of human social and personal relationships, and given its central focus on desire, we must expect negative gendered portraits. And given the patriarchal nature of French society, a level of misogyny is to be expected. But do we find more evil (treacherous, ruthless, murderous) women than evil men? This study suggests that we don't.

Burch and Sellier's claims for the deep misogyny of French cinema (as a whole) cite four key noirs: ‘The real balance of power is to be read in the box-office successes of the most misogynistic films (Panique; Quai des Orfèvres; Manèges; Manon) and in the increasingly spectacular failures of films taking the opposite stand.’6 In fact neither Panique nor Manèges were huge box office successes and Signoret's positive prostitute fatalitaire figures in Macadam and Dédée d'Anvers were more popular (see Appendix 2). While one can certainly conclude that all these ‘most misogynistic films’ present women as inferior to men in various ways, none feature heartless spider women. Indeed, the present study has argued that the lead female roles of both Orfèvres and Manon are romantic fatalitaires rather than evil garces. Signoret's character in Manèges is a gold-digger but she is also an amoureuse, like several other demonic French fatales, including Alice in Panique. This latter film might just as easily be categorised as a fatal man narrative, since Alice is in a sense a victim: seduced and manipulated into framing the hapless, love-struck Hire by her narcissistic, sociopathic boyfriend, the real murderer.

Of my corpus of 75 classic French noirs (1946–59), films that present the most powerful negative images of women are generally not as common or popular as those featuring romantic fatalitaires (Appendix 2). Of the top grossing noirs (1946–59), only Diaboliques features a bad girl as major antagonist. The film featuring the most ruthless and murderous femme, Voici le temps des Assassins (1956) was a commercial disappointment (1,538,259; 51/81), despite the presence of Gabin, two years after his return to stardom. And while French noirs contain many minor female antagonists as petites garces, films foregrounding flawed or toxic masculinity and fatal men (though many of the latter redeem themselves in extremis) are just as prevalent as those featuring major female antagonists during the classic period (Appendix 2).

Noir as sociohistorically inflected dramas of mate selection

Underpinning cultural difference, I have read noir narratives as dramas of mate selection. For the femme, the central predicament, amplified in patriarchal societies, is that of juggling between often conflicting needs for love and money. The emotionally frigid spider woman, rare in French noir, abandons romantic attachment in favour of economic independence. But other noir females' strong desire for a long-term romantic partner, coupled with their need for material security often pit them (and their lovers) against competitors, jealous and often powerful rivals, possessive spouses and oppressive social forces. Moreover, males' preference for younger women means the femme is always racing against the clock to capitalise on her erotic potential.

Questions around the femme's moral or criminal guilt or innocence must be read in terms of the fundamental issues of emotional/sexual fidelity. Although fears of women's economic independence may be displaced into the sexual arena, sex is what underlies epistemological uncertainty and male paranoia in noir, though not in any Freudian or Lacanian sense. In evolutionary terms, it is sexual jealousy and ultimately uncertain paternity that make the fatale ‘simply a catchphrase for the danger of sexual difference and the demands and risks desire poses for the man’.7 For protagonist and spectator alike, the question of the femme's (sexual attractiveness and) sincerity is the crucial and fundamental issue in film noir, and not an unconscious Oedipal investigation of traumatic sexual difference, as canonical psychoanalytical accounts have claimed. It is for this reason that the blackest of classic American noirs – in which the woman is the official socio-legal property of a male antagonist – are those in which the duplicity of the fatale is either established beyond a shadow of a doubt, or worse still, remains unanswered, creating a vortex of ‘epistemological uncertainty’8 and paranoia into which the narrative swirls and disappears, often taking both hero and fatale with it.9 We have seen that most femmes in French noir are either less overtly sexual or less duplicitous, or both, resulting in a lesser focus on this type of manic visual investigation.

The relative scarcity of professional women in my noir corpus (as in French cinema as a whole) is clearly reflective of French women's lesser socio-economic and politico-legal status or structural power as compared to American women. The crisis of masculinity in postwar France is fuelled more by fears of ‘unruly’ female sexuality than by the threat of women's economic independence (only just beginning to emerge). I have read the latter sociohistorical fact as underpinning the quasi-absence of the powerful spider woman in French noir, as opposed to the more common demonic amoureuse. On the other hand, on both sides of the Atlantic, women's weak dyadic power (due to historically low sex ratios and an excess of unmarried women) feeds into multiple expressions of female sociosexuality, producing sexually assertive female characters as both antagonists and good-bad girl protagonists. In France this gender imbalance also underlies the frequency of fatal men narratives, which correspond loosely to the American female gothic.

French fatale as romantic fatalitaire

The predominant female figure in classic French noir, the good-bad girl or unruly romantic fatalitaire, is constructed positively as loyal mistress and often also as tragic heroine. The fatalitaire (paired with an ill-fated lover in 18 films) appears in a total of 33/75 French noirs (Appendix 2), while the evil garce or murderous demonic fatale is a major antagonist in only 14. While often a socially marginalised figure – adulteress or prostitute –the fatalitaire may also be a member of ruling elites. Whatever her social standing, the fatalitaire drives a narrative in which romantic (genetically driven) love is seen as morally purer than traditional (resource or status driven) marriage or ‘protective’ sexual arrangements (e.g. pimps and prostitutes) by which older, corrupt or more powerful male antagonists assert property rights. Admittedly, in the classic period, the threat to the established order posed by the fatalitaire and her lover is partially contained by means of narrative punishment. Only partially, however, since society's verdict, whether meted out directly via the law or indirectly via the workings of fate, is constructed as tragically unjust, reinforcing spectator sympathy for the fatalitaire and her lover, thereby questioning the patriarchal order that condemns them.

Despite the prevailing cynicism and misogyny of postwar French cinema, the most salient and surprising fact of French noir is that, in this bleakest of cinematic optiques, romantic love not only survives, but figures in some of the most popular and critically acclaimed films of the period.

French noir as an evolving constant

By defining noir broadly, as a cinematic optique or way of viewing the world, rather than a geographically or historically situated cycle, this study suggests that French noir contains a cluster of aesthetic and thematic constants. I have argued that these correspond to a set of universal human concerns around reproductive and economic striving. However, I have also demonstrated that French noir is a set of sociocultural artefacts that cannot but be inflected by and respond to contingent, evolving sociohistorical realities, like war, demographic shifts and modernisation.

Thus we have seen how the romantic pessimism that characterises 1930s poetic realism is largely replaced by lighter comedic crime dramas and female-centred melodramas during World War II, as French cinema strove to provide messages of hope to an embattled nation. During the postwar period, however, once Liberation euphoria subsided, once the bitter realities of the Occupation could no longer be papered over with Resistance triumphalism, and with the slow pace of economic recovery, French noir became marked by a darker, more cynical realism, known as le réalisme noir. Moreover, as modernisation gathered speed during the second half of the 1950s, changing gender roles began to be reflected in the appearance of female characters with increasing levels of agency. Nonetheless, I have also argued that poetic realist romanticism remains an important thematic and stylistic trend in French noir throughout the 1950s, as evidenced by the persistence of the trope of the star-crossed lovers. Moreover, films like Ascenseur pour L'echafaud and Du rififi chez les femmes demonstrate that this trope is highly compatible with modern, egalitarian discourses around gender.

Directions for future research

Ending this study in 1959, at the dawn of the Fifth Republic and on the cusp of the New Wave inevitably raises questions. What happens next? Volume 2 will attempt to provide some answers. I will investigate the continuing story of gender in French noir, from the upheavals of the New Wave to the present, notably charting the impacts of the sexual revolution of the 1960s and second wave feminism; the gay rights movement; globalisation; immigration, and the continuing ‘dialogue’ with America.