CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

THE MEMORY CHAMPION’S LIFE: MAKING SPEECHES

As well as being expected to display impeccable memorization of every new person I met, I soon started to appear on TV shows to demonstrate my memory skills. Imagine: here I was, a man who as a kid had had no self-esteem at all. Now, all of a sudden, I had to learn how to present myself intelligently, express my thoughts clearly and overcome shyness in front of potentially millions of people at any one time. Thank goodness that proving to myself I had good brain power had done wonders for my confidence!

Even so, public speaking certainly wasn’t my thing, and apparently I was in good company. The 19th-century American author Mark Twain (of Huckleberry Finn fame) was the guest speaker at a dinner with all the great leaders of the American Civil War. After they had made their long, heavy-going speeches, Twain stood up nervously to say, “Caesar and Hannibal are dead, Wellington has gone to a better world and Napoleon is under the sod. And, to be honest, I don’t feel too good myself” – and promptly sat down. Things don’t seem to have changed with time, either: in the USA a survey has claimed that many people fear making a speech in front of others more than they fear death!

Naturally, the greatest cause for speech anxiety is that your mind will go blank and at best you might start to babble something vaguely coherent, while at worst no sound comes out at all. In which case, read from notes, right? However, think about the most impressive speeches you’ve heard. Are they read by someone whose eyes look down and whose hands turn over pages? Probably not. The most engaging, inspiring speeches are those given by a speaker who makes eye-contact with the audience, smiles at them and talks as if it all comes naturally. Memorize your speech and people will love to listen. And that’s exactly what I had to master when I started giving talks, both on and off camera.

Be prepared!

A poorly prepared speech gets you off on the wrong footing. One of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever been given about delivering a good speech is, “Say what you are going to say, say it, then say what you just said.” If you plan your speech before you write it, you can make sure that you edit out any information that’s irrelevant or boring and structure the speech coherently, before you actually start writing the speech itself.

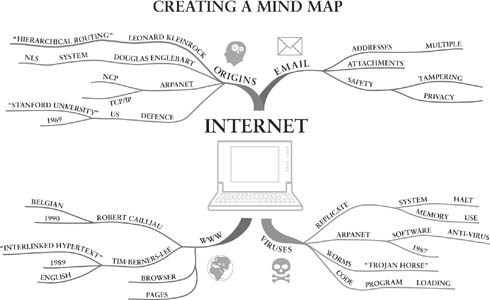

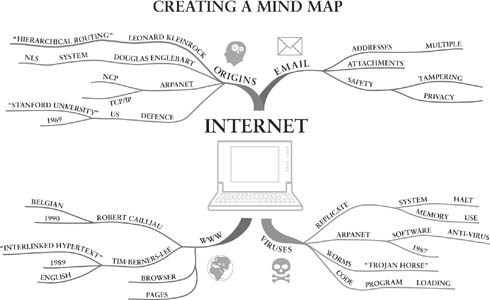

One of the best methods of preparation is a Mind Map®. Devised by Tony Buzan, co-founder of the World Memory Championships, Mind Maps provide a visual means by which to organize information around a central topic. In the centre of the “map” is the topic itself (the topic of your speech, in this case) then, as ideas and thoughts come to you, branches lead out from the centre, breaking down until you have a complete picture that shows everything you want to say. The aim is that this overview shows you where the links are between the elements of your topic, giving you a natural, coherent organization.

In a Mind Map® the main subject topic appears in the centre of the picture, and key ideas and pieces of information radiate outward. The picture enables you to organize information logically, so that you can construct a coherent speech, while also creating a visual memory trigger.

Let’s say your speech is about the Internet. You write the word “Internet” in a circle in the middle of a sheet of paper, or perhaps you draw a computer. To make your Mind Map especially effective, you use a different colour for each main branch that leads from that central image – it’s much easier to navigate around your map if it’s colour-coded, and much easier to recall (think about how difficult it would be to navigate the map of a metro system if the different lines weren’t defined by colour). Perhaps you could use brown for email, red for viruses, green for the World Wide Web, yellow for the origins of the Internet, and so on. From each of these main branches, sub-topics (sub-branches) will occur to you. You can use a combination of icons and single-word descriptions to organize the sub-topics along their appropriate main branches.

The great thing about this tool is that it allows your brain to work randomly and creatively in planning your speeches, because it is not confined to the restrictions of linear preparation. You can attach topics and sub-topics as they occur to you without having to finish one before moving on to another. Once you’ve finished, with all your topics in full view, you can use your judgment about which branch you talk about first, and how to continue, until you’ve covered all the branches. I number the branches and subbranches to create the most natural, logical order of presentation.

Once you’ve decided how to organize your speech, make a numbered list of the main points in order, using the numbers on your Mind Map as a guide. For a short speech I usually get this down to five bullet points (each bullet represents about two to five minutes of talking time) – although a long talk will probably have up to 20. Once you’ve got your bullet points, you just need to memorize them using the Journey Method.

Applying a journey to your speech

The Journey Method provides you with the perfect memory aid to keep you on track during your speech, because you imagine yourself moving from point to point through the journey. If someone interrupts you with a question, you can immediately take yourself back to the position in the journey at which you were interrupted and pick up from where you left off.

So, once you have your bullet points, you need to give each one a visual representation that you can place at each stop on your chosen journey (I have several favourite speech journeys I store in my memory journey bank). I try to keep my visual cues as simple as possible, but when you first start out, you may need to replay a little scene in your mind at each stop to remember certain things that you want to say – such as a relevant date.

In the speech about the Internet, you might start with information about its origins. The Internet was believed to have been born out of systems used for US defence. If my journey begins at my front door, I visualize this as Barack Obama pushing a big red panic button, which takes the place of the doorbell. This is enough to trigger the research I’ve done about the particular defence strategy that the Internet was used for. But how can I be sure to memorize 1969, the year that it all happened?

Using the Dominic System, 1969 gives me AN and SN, which I convert to the Swedish scientist Alfred Nobel (of Nobel Prize fame) and the actor Sam Neill. I imagine Alfred Nobel on a dinosaur (my prop for Sam Neill, who starred in Jurassic Park) coming to the door to give Barack Obama a prize. These images are enough to let me talk for a few minutes on the origins of the Internet. Once I’ve begun the speech, the visual memory of the Mind Map comes back to fill in some blanks. In the meantime, I mentally move to the next stop on my journey and the next point.

Applying the Link Method

I have many clients, ranging from TV personalities to businessmen and -women, who come to me for regular help with memorization techniques. One such client is a top British comedian. Years ago, he got into the habit of using an autocue to help him recall the gags in his act. The rolling script in front of him gave him two- or three-word descriptions of each gag or mini-routine. As he told one gag, he could see the cue words for the following gag come up on the autocue. Initially, the system worked well – his cue words for each gag were enough to help him stick to the sequence of jokes without it looking as though he were reading from the autocue. However, gradually his confidence in his own memory slipped away and he began to use more and more words on the autocue. Instead of just one or two words per gag, he was using one or two cue words for each element of a gag, which meant that the overall routine looked less and less natural. The autocue was acting as a substitute for his working memory. When the severe doubts crept in, he called me for help.

I introduced him to the Journey Method – and he was a natural. A comedian with a highly creative imagination, he has no trouble using a mental journey to separate out the elements of each anecdote or joke and post one element at a time as a coded key image at the relevant stage of a route. He could use as many cues as he wanted per gag, because they were all in his head, so it never appeared to the audience as though the routine was scripted.

However, the Journey Method alone didn’t help him go from one gag to the next, and that’s why he incorporated the Link Method (see pp.37–42), too: as he gets to the end of one joke (the end of his journey), he sees a key image of the next gag cued up in his imagination and waiting for him. This acts as a memory trigger. For example, let’s say the story he is telling is set on a riverboat and the gag that follows involves his uncle. As he delivers the punchline about the riverboat, he then sees in his mind’s eye his uncle standing on the riverbank in a familiar pose. The key image of his uncle acts as a memory prompt or mental cue to allow him to move confidently on to the next joke in his repertoire (and that is enough to start him off on his next journey).

EXERCISE 12: Stand-up Comedian

How many times have you heard a comedian rattle off a series of short gags, promised yourself you’ll remember them to tell your friends, but then completely forgotten them? The Journey Method can change that for ever. Create an associated image for each of the following ten jokes, then link that image to stages on a ten-stop journey. Test the effectiveness of your links by doing a little stand-up show for a willing friend! Repeating five or six jokes in a row from memory is good; seven or more is excellent.

1 A little girl said to her dad that she’d like a magic wand for Christmas, and then added, “And don’t forget to put the batteries in!”

2 The lottery: A tax on people who are bad at maths!

3 Suburbia: Where they tear out the trees and name the streets after them!

4 A Buddhist monk walked up to a hot-dog stand and said, “Make me one with everything!”

5 Money talks. Mine generally says “Bye!”

6 Why was Santa’s little helper depressed? Because he had low elf-esteem.

7 If at first you don’t succeed, skydiving isn’t for you.

8 Animal testing is a terrible idea – they get all nervous and give you the wrong answers!

9 If you told a cow a really funny joke, could she laugh so much that milk came out of her nose?

10 You know, when you’ve seen one shopping centre, you’ve seen a mall!

This combination of using a familiar route to memorize the elements of a funny story or gag and the Link Method to connect the stories or gags together guarantees him a completely polished and convincing performance.

Of course, working in this way is not just for stand-up routines – it can also work for long speeches or talks. For example, if you’re conducting a training session for a group of new recruits in your field of work, you’ll have several topics to cover over the course of, say, a morning. The company’s structure, the ethos of the working environment, the main duties of the job, the telephone systems, and so on, are all aspects of a new job you may have to impart. In the same way that a comedian creates a journey for a particular gag and uses a link to go from one gag to the next, you would use one journey per topic and then use the Link Method to conjure up a visual symbol of the following topic at the end of each journey. The possibilities for the system are endless.