THE FERRYBOAT WAS moving. One ferryman had joined the other on a platform in the stern and the two of them, facing each other, were swaying a long sweep to and fro. The sweep was not straight, but had a kink in the middle of it.

‘It works on that pivot,’ said John. ‘But why do they have an elbow in it?’

‘Make it go cockeye,’ said Nancy. ‘First one side and then the other.’

‘Like sculling,’ said John, watching the blade of the sweep which turned one way when going from port to starboard and the other way when going from starboard to port.

The thought of sculling reminded them both of working their little dinghies with an oar over the stern in and out of narrow places on the lake at home in the faraway north.

‘Gosh, I wish they hadn’t bagged Swallow,’ said John.

‘And Amazon,’ said Nancy.

But being afloat, even if they were only crossing a river in a broad flat-bottomed Chinese ferryboat, made everybody feel better. They were on water again, and moving, and they felt like fish that had been flapping about on dry land and had somehow got back into the sea. They forgot that they were prisoners, forgot the painful shape of Chinese donkey saddles, and, with the eyes of six experienced seamen, looked at the small sampans tethered to poles along the bank or lying astern of the big fighting junks in the anchorage, and admired the skill of the ferrymen working their long sweep.

‘Why are we going along the shore instead of straight across?’ asked Roger, pointing over the river to the landing-place on the further side, where there were men waiting on a jetty and they could see walls and roofs among the trees.

‘Current,’ said John. ‘They’ll work upstream before crossing. No good going straight and being swept too far down. Look how the water’s swirling past those junks.’

‘Beast of a current,’ said Nancy. ‘Just you try working against it with nothing but a bottom board.’

‘The junks have all got eyes,’ said Titty, seeing the big black and white eyes painted on their bows.

‘See their way about,’ said Roger.

‘I say,’ said Nancy. ‘That’s our junk. Look at the guns poking out. They must have brought her up since yesterday. Drying the mainsail. Look, John. You see what I meant when I told you they had about a dozen sheets to each sail, one to every batten.’

‘Why don’t they have the ferry at a narrower place?’ said Susan.

‘Current’s worse in the narrows,’ said John. ‘Here they get a bit of slack water each side.’

The ferryboat was being slowly driven upstream twenty yards or so out from the shore. Already they were well above the landing-place. On the opposite side they could see where a wall ran down to the water’s edge. The town itself was hidden by trees and they could see nothing of it but a tower and a flagstaff.

‘I say, there’s a lovely creek over there,’ said Roger.

‘And a baby junk in it,’ cried Titty. ‘Just like the big ones, only smaller.’

‘Perhaps that’s where we’re going to land,’ said Roger.

John looked at the curl in the water pouring down the middle of the river. ‘We aren’t,’ he said. ‘They’re beginning to work her out already. We’ll hit the other side just about opposite where we started from.’

The ferrymen were working harder now. They were chanting as, facing each other, one pulling, the other pushing, they swayed to and fro across the platform in the stern. The ferryboat was moving out into the stream, still heading up, but being swept down faster and faster as it came out into the main current.

There was a sudden yell from Nancy. ‘Giminy!’ she shouted. ‘Look! Look! There’s Amazon, pulled up in that creek, and Swallow just beyond her.’

‘Where’s that telescope?’ said John.

Titty began fumbling at her pocket. ‘Better not,’ said John, remembering where they were. ‘They might grab it.’ Titty pulled out a handkerchief and blew her nose instead.

They had been staring at the little junk in the creek, bright in scarlets and blues with a streak of green along her bulwarks and green tops to her three masts. Just for one moment they were able to see their own little boats, and then, with a tug at their heartstrings, they lost sight of them as the ferryboat moving across drifted down below the opening into the creek. A moment later even the green tops of the little junk’s masts were hidden by the trees. They turned to see that they were dropping fast downstream towards the bigger junks at anchor.

‘Hee . . . yo . . . hee . . . yo,’ chanted the ferrymen.

‘We’re going to hit that first one,’ said Peggy. ‘We are.’

‘Good work,’ cried Nancy, as, with a tremendous effort the ferryman drove their boat clear. They just missed the anchor hawser and swept past the big junk almost near enough to touch it, while men in pointed straw hats looked down on them and jeered as sailors always do jeer in harbour at other sailors who have narrow shaves of bumping their new paint.

‘Hee . . . yo . . . hee . . . yo,’ chanted the ferrymen. The sweat was pouring in streams down their naked brown backs, and dripping from their faces on the wooden platform. But already the boat was sweeping past the last of the anchored fleet and was coming quickly nearer to the other side of the river. A sampan with some Chinese in long robes and others with rifles like their own guards, had left one of the junks and was racing them for the jetty.

‘More prisoners,’ said Nancy, almost as if she were herself one of the pirates.

The sampan and the ferryboat reached the jetty together. The men from the sampan scrambled ashore with their prisoners and set off at a run up from the landing-place towards a gateway in the brown wall of the town. Their own guards shepherded them ashore and, falling in beside them, marched them briskly after the others.

‘Why isn’t Uncle Jim here to meet us?’ said Peggy.

‘Probably smoking a pipe of peace with the pirates,’ said Nancy.

‘Not if Miss Lee’s like the great-aunt,’ said Roger.

‘She isn’t,’ said Nancy. ‘She’s a pirate. Don’t be a galoot.’

‘If Captain Flint’s found someone who can really talk English,’ said Susan, ‘he’s probably getting a telegram sent home to say we’re all right.’

‘But are we?’ said Peggy.

‘We’re jolly soon going to be,’ said Nancy.

Through the gateway they passed into something much more like a town than Chang’s village on Tiger Island. There were many more houses, for one thing, though there seemed to be very few people. The streets, between the low, green-roofed houses, were not paved, but just earth trodden smooth. Pigs were wandering about. There was the harsh trilling of grasshoppers in the trees. Dust rose about their feet. A big blue butterfly fluttered across the street above their heads. Here and there women were sitting in the open doorways. A small boy sitting in the dust and tootling to himself on a long bamboo flute took his flute from his lips and stared at the prisoners as they went by. But, for a town, the place seemed empty.

‘There’s an awful lot of people somewhere,’ said Roger. ‘Can’t you hear them?’ Suddenly he pointed. ‘They’ve got a dragon here too.’

Here, as in Tiger Town, women squatting in the dust were stitching away at the partly unrolled body of a dragon. Its huge grinning head lolled on the ground. Part of the body lay like a narrow carpet where the women were working at it. The rest was like a carpet rolled up for storage.

‘I say, it must be a mile long when they spread it all out,’ said Roger. ‘It’s a new one. The head hasn’t been painted yet. I say, I wish they’d let us stop and have a look at it.’

There was no chance of stopping now. The guards hurried them along, and all the time, though there seemed to be no one about, the noise of a crowd grew louder and louder. Suddenly they turned up a short road that ended in a sort of three-storied tower with a gateway under it. Here they were stopped. Questions were being asked and answered by their guards.

‘Passwords,’ said Nancy. ‘This is the real thing.’

‘Pretty fair scrum,’ said Roger, looking through under the arch.

‘I do think Uncle Jim might have come out to meet us,’ said Peggy. ‘What’s that clicking noise?’

Through all the noise of the chattering crowd there came a queer sound of clicking, now stopping, now going on again, as if people were dropping pebbles on a hard floor.

‘We’ll know in a minute,’ said Susan.

‘Now,’ said Titty under her breath.

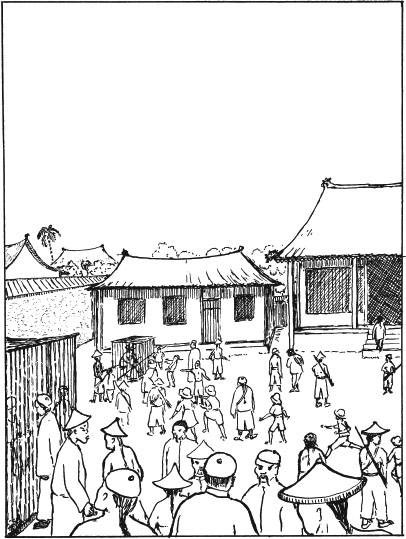

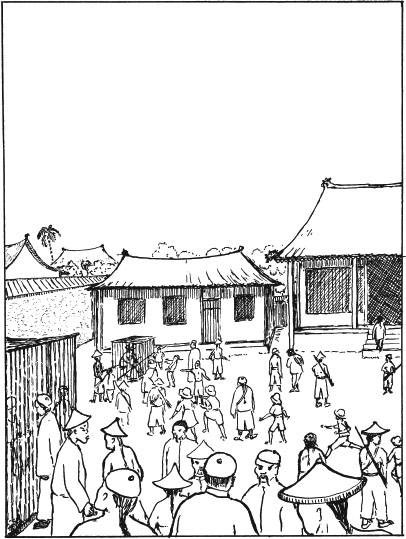

A guard gave a tug at her sleeve. She remembered quickly to keep grinning. With their guards all round them they walked through the gateway into a shouting crowd of Chinese. The din was like the noise of a street market. They were in a courtyard like Chang’s, only very much bigger, sloping gently up to the steps of a big, steep-roofed building with a wide verandah in front of it. Up there, over the heads of the crowd, they could see two banners, one, the green banner with Chang’s black and orange tiger on it, the other a banner with something like a huge grey tortoise on a scarlet ground. There were more buildings on either side of the courtyard. Some of these, too, had open verandahs three or four steps up, and there, above the level of the crowd, were men with shaven heads squatting on the floor busy flicking beads to and fro on wires strung in wooden frames.

‘Look, Peggy,’ said Roger. ‘That’s what that noise is.’

‘Abacus,’ said Titty. ‘There’s a picture of it in Petit Larousse.’

‘I know,’ said Roger. ‘Doing sums.’

‘Hullo,’ said Nancy. ‘There’s our captain.’

They were glad in all that crowd of strangers to see a face they knew, even if it was the face of the captain of a pirate junk. Nancy made as if to go and speak to him, but was stopped at once by the guards.

‘Our’ captain was talking to one of the prisoners who had been brought ashore in the sampan. The man took a bag out of his sleeve and offered it to him. The captain did not take it but motioned to a man standing by him who took the bag and passed it up to another man waiting on a verandah above him, who turned it upside down, emptying a great stream of silver dollars on the floor in front of one of the squatting men. One of the dollars rolled off and came to Roger’s feet. He picked it up, looked at it and gave it to a guard who passed it up to the man on the verandah. The man squatting on the floor quickly sorted the money into little heaps. He had a pair of brass scales in which he weighed each heap separately, pouring the money from the scale into a general pile. Each time he did this he flicked a bead across the abacus. When he had done he nodded and spoke to the captain. The captain and the man who had brought the money bowed to each other. The captain spoke to the guards who went off with the man towards the upper end of the courtyard.

‘What was he doing?’ asked Roger.

‘Paying a ransom, I bet,’ said Nancy.

The captain, looking very pleased with himself, turned and saw them.

‘Talkee English, bimeby,’ he said.

‘Where’s Captain Flint?’ asked Nancy. ‘San Francisco,’ she added, remembering what the Taicoon had called him last night.

The captain pointed up the yard and led the way through the crowd followed by the guards with their six prisoners. Where the crowd was thickest they found a barred enclosure like a lion cage at the zoo, divided into compartments. Outside the first of them the elderly man they had seen paying the ransom was eagerly talking to another elderly man behind the bars. The two of them, the man in the cage and the man outside, were exactly alike.

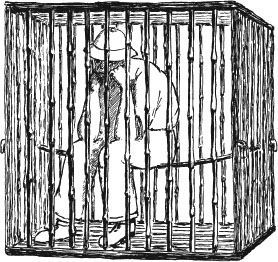

‘Blothers,’ laughed the captain over his shoulder. He pushed on. The crowd parted before him and suddenly they were looking at Captain Flint. He was sitting on a narrow perch in a bamboo cage in which there was only just room for him. The cage was indeed very like a hen-coop, and it had long carrying poles, like Chang’s chair. The captain smacked the head of a small boy who, with the long feathery tip of a green bamboo, was tickling Captain Flint through the bars.

‘Why haven’t they let him out?’ said Nancy angrily.

‘Oh, I say,’ said Titty.

Susan and John looked at each other. Their hopes that Captain Flint had been able to put everything right had faded suddenly away.

‘Hullo,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Four, five, six. All complete except for the parrot and that blessed monkey. Had a good night? All well so far.’ He shifted on his narrow perch and rubbed the sore place. ‘I wish they’d buck up and let me out. It would take a parrot or a vulture to sit comfortably on this thing.’

Nancy’s captain was listening as if to strange music.

‘Talkee English, bimeby,’ he said. ‘Talkee English. Talkee Melican. Missee Lee talkee evellything.’

‘All right old chap,’ said Captain Flint. ‘But I’d like to be able to stand up.’ He shook one of the bamboo bars of his cage.

‘Too much stlong,’ said Nancy’s captain.

‘What do you think’s going to happen?’ asked John.

‘Blest if I know,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Keep smiling. That’s the ticket.’

‘Have you had anything to eat?’ asked Susan. She dug in a pocket and brought out a bit of chocolate. ‘It’s a bit sticky,’ she said. ‘I meant it for Roger yesterday.’ She held it out and Captain Flint took it through the bars, winked at Roger, unwrapped it and sat on his perch thoughtfully chewing. The watching crowd roared with laughter.

‘Oh, all right,’ growled Captain Flint. ‘Feeding the apes, eh? Like to see my celebrated gorilla act?’

‘No, no,’ said Titty. ‘You’ll only make them cross. And they’ve been quite all right so far . . . except about putting you in a cage,’ she added hurriedly.

‘If only they’d let me have a word with somebody who really does talk English,’ said Captain Flint.

Suddenly the air shook with the throbbing boom of an enormous gong. The whole chattering crowd in the courtyard was silent, waiting as the waves of sound slowly died away. Again the gong boomed. Again it was as if the whole world throbbed like a pulse.

‘Gosh,’ said Roger, looking round at Susan with startled eyes.

Again the gong boomed and again. Each time there was a long pause until the last wave of sound had died, and then, yet again, came that tremendous booming noise.

‘Eight . . . nine . . . ten . . .’ Titty was counting. ‘It’s for Chang . . .’

But the gong was still booming. Again and again that single, powerful noise broke each new silence. It was as if someone were throwing pebbles one by one into a pool, waiting till the last ripples were smoothed away before dropping the next pebble in the still water. Eighteen . . . nineteen . . . twenty . . . twenty-one . . .

‘Missee Lee . . . Twenty-two gong,’ said the captain, and went off through the crowd and up into the large building at the head of the courtyard.

For the last time the gong boomed and with that twenty-second gong stroke, they saw that everybody was looking in one direction, towards the tall flagstaff that towered above roofs and trees alike. A huge black flag was rising jerkily to the top of the flagstaff and on it a monstrous golden animal seemed to dance as the light wind rippled the flag.

‘It’s a dragon,’ said Titty.

‘I can see it isn’t a skull and crossbones,’ said Nancy.