AS THE THROBBING of the last gong stroke died away a sort of sigh that sounded like ‘Missee Lee’ rose from the crowd. Everybody was looking towards the steep-roofed building at the head of the courtyard. Men with rifles came out on the verandah, thumped the butts of their rifles on the wooden floor, and waited. Presently an old man came out on the verandah and stood at the top of the steps, with a roll of paper in his hand. There was silence. He let the paper unroll, looked at it and called out a name. There was a stir in the crowd. A guard opened a gate in one of the cages, and the two brothers, the prisoner from inside the cage and the other who had paid over all those silver dollars, were led off up the steps to the verandah and into the building.

The hubbub of talk broke out again, and through it, all the time, they could hear the clicking beads of the accountants doing their sums.

‘Believe it’s a sort of settling day,’ said Captain Flint.

‘We saw them weighing silver money,’ said Nancy.

‘What did they weigh them for?’ asked Roger.

‘To see somebody hadn’t clipped the edges,’ said Captain Flint. ‘That used to be a great game in these parts.’

‘Do you think it’ll be our turn next?’ asked Titty ‘I wish we could get it over . . .’

‘What are we going to settle with?’ said Captain Flint. ‘We’ve got no bags of silver. Paying business this seems to be. But I’ll do my best.’

‘Tell them we’ve simply got to get to Hong Kong or somewhere,’ said Susan.

‘Don’t let’s hurry,’ said Nancy. ‘We’ll never have a chance like this again.’

‘I like that,’ said Captain Flint. ‘You just try sitting in this cage.’

There was another silence. The old man at the top of the steps was reading out another name. The two brothers came out smiling happily, bowing in all directions, even to the guards. Another prisoner was taken in. He came out and yet another name was read.

‘It’s like waiting to see the headmaster,’ said Roger.

‘Our turn’ll come all right,’ said Captain Flint. ‘No good worrying till it does. Look here, John, let’s hear exactly what did happen that night. How did you get ashore? Were you anywhere near when that blighter picked us up and wouldn’t stop to look for you?’

With help from the others, John told the story of that windy night, of how he had put the sea-anchor out and made sure that the rope should not chafe, of how he had fallen asleep and been waked by a splash and guessed that something had gone wrong, of how he had begun hauling in the rope (‘We got broadside on and I knew I was wrong, so I let it out again, and after that she was dry enough.’) He told of hauling in the rope next morning when the wind had dropped and finding the sea-anchor no more than a few rags at the end of it. ‘Wonderful what a warp over the bows’ll do,’ said Captain Flint, ‘to keep a little boat safe in a big wind.’ Roger told of the tannic jelly put on Gibber’s scorched arm; Susan of the struggle to relight the lantern. Even Titty, as the story of that night’s drift was being told, forgot her present worries, remembering them only in the silences when new names were being called from the steps, and junk captains and guards were swaggering up into the big building, or swaggering down again. Sometimes on coming down those steps prisoners and guards would go to the accountants squatting over the sums and clicking their beads. Sometimes the prisoners were marched straight out of the courtyard. Meanwhile the tale went on. ‘What was the first thing you saw?’ asked Captain Flint. They told of the dawn coming up behind them out of the sea, and the hills, and the big cliff and the landing on the tiny island.

‘And the first thing I found when we got ashore,’ said John, ‘was that I’d got your sextant and the nautical almanac in Swallow. I’d meant to put them in Amazon, but in all that rush . . .’

Captain Flint half jumped up, and hit his head on the roof of his hen-coop.

‘You’ve got my sextant! Good for you. And I thought I’d lost it for ever. Where is it now?’

‘It’s in Miss Lee’s temple,’ said Titty.

John was just telling how they had found the stone chair on the island, and the little house where they had spent the night when a new name was called from the verandah.

‘There’s our captain coming,’ cried Nancy. ‘There. He’s coming down the steps now.’

The junk captain was hurrying towards them. He clapped his hands and shouted, and two enormous half-naked Chinese pushed their way through the already thinning crowd and joined him by Captain Flint’s hen-coop.

The junk captain turned to Nancy. ‘Him too much stlong,’ he said.

The two big Chinese stood outside his cage, glaring at Captain Flint, bending their arms and making their muscles stand up. They slapped their knees. They beat their chests like great apes.

‘What are they making faces for?’ said Roger.

‘Two can play at that,’ said Captain Flint cheerfully, and began making faces in return. He got off his perch, crouched with bent knees, took a bar of the cage in each hand, shook them and growled. ‘This is the gorilla act,’ he said. There was a gasp from among the watching Chinese.

The two big men hopped up and down. Captain Flint, growling, did the same.

‘Don’t make them angry,’ said Titty.

‘Fun for their money,’ said Captain Flint.

‘They’re opening the cage,’ said Roger.

The cage door opened and Captain Flint came out and tried to stretch himself. Each of the two big Chinese grabbed one arm. The junk captain, again with a glance at Nancy, brought a pair of handcuffs from behind his back and clapped them on Captain Flint’s wrists.

‘Oh,’ said Titty.

But Captain Flint just jingled the handcuffs as if they were ornaments and smiled at the Chinese.

‘Stout fellows,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Too much strong. Look at them now. Pleased as Punch. It’s just as well to make everybody happy. As for you, you son of a gun,’ he added, turning his head towards the junk captain, ‘if ever you get wrecked and I pick you up at sea . . .’

The junk captain bowed politely. ‘Talkee English, bimeby,’ he said.

With jangling handcuffs Captain Flint walked off between the big Chinese, the junk captain walking beside them. They went up the steps to the verandah and were gone.

‘It’s going to be all right in a minute,’ said John.

‘But they’ve put him in chains,’ said Titty.

‘What else could they do?’ said Nancy. ‘He is pretty strong, and anybody who saw him being a gorilla would think it wasn’t safe to let him out.’

‘He didn’t mind,’ said Peggy. ‘Didn’t you see him wink?’

‘So long as there’s somebody who knows English,’ said Nancy. ‘Not this gabble that’s no good for asking or explaining anything. If there’s somebody who really does know . . . And I’m sure there is. Our captain’s been saying so all the time.’

‘Missee Lee knows English all right,’ said Titty. ‘Oh, I say. We’ve never had time to tell him about those books . . .’

‘Or about using her Primus,’ said Roger hurriedly.

Susan glanced at him but said nothing. There was no more talking among the little bunch of prisoners waiting with their guards beside the empty travelling cage, watching, watching for Captain Flint to come out again on the verandah at the top of those steps. They had expected him to come out at once. One word of explanation would surely be enough and he would come charging out to fetch them in, and the next thing would be to arrange for them to get to a proper port and go aboard an English ship. Minute after minute went by and still no new name was shouted from the steps and nobody went in or out.

Half an hour went by. Titty caught John and Susan looking at each other as if they thought that something might have gone wrong. Even Nancy was looking less confident. ‘I say,’ whispered Roger, ‘you don’t think he’s got in a row about that book. Shall I bolt in and tell them I did it?’

‘Keep quiet,’ said John, ‘and keep grinning.’

At last they saw Captain Flint coming out.

‘They’ve taken off those handcuffs,’ cried Roger.

But Captain Flint did not look as if anything was settled. He came down the steps with a grave, puzzled face, the junk captain beside him and the two big guards walking behind.

‘He’s free anyhow,’ said Titty.

But the little group came straight across the courtyard to the bamboo travelling cage. The junk captain stood at the door of the cage and bowed. Captain Flint bowed to him, stooped, went in and sat down on his perch. The door of the cage was closed once more.

‘What is it? What is it?’ asked Nancy.

‘Why are they shutting you up again?’ asked Roger.

‘Are they sending a message home?’ asked Susan.

‘Is Missee Lee a she or a he?’ asked Nancy.

‘Doesn’t she talk English after all?’ asked Titty.

‘Rum go. Rum go,’ said Captain Flint. ‘Blest if I know what to make of it. Jabbering Latin . . . Asked if I knew Greek. Asked . . . Gosh! I’ve left school too long . . . You people’ll be all right if you keep your heads. Where were we going? What were we doing? That’s all right. But Cambridge? Cambridge? Why Cambridge? Must have meant Cambridge, Massachusetts . . . Well, of all the rum goes. What’s that? Does she talk English? English? English? I should think she does. She knows more English than I do . . .’

He was still muttering to himself when there was a sharp call from the steps. The junk captain gave an order to the guards and John, Susan, Nancy, Peggy, Titty and Roger found themselves being marched towards the big green-roofed building at the top of the courtyard.

‘In for it now,’ said Nancy, confident once more now that the moment had come. ‘Look here, John. She’s a she-pirate. Let me do the talking.’

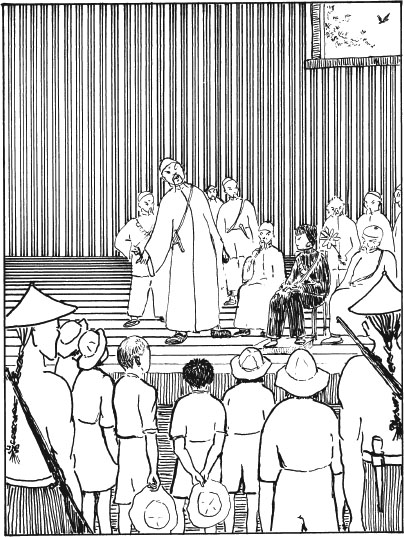

They were marched up the steps, across the verandah between men leaning on their rifles into a large, cool room that for a moment seemed dark after the sunshine in the courtyard. At the far end of the room there was a small group of people on a raised platform one step up from the floor. They saw Miss Lee at once. A tiny Chinese woman was sitting on a straight-backed chair. She had a black silk coat and trousers, and gold shoes that rested on a footstool. She was wearing a cartridge-belt over her black silk coat and her fingers were gently tapping a large revolver on her knees. An old Chinese woman was standing behind her chair and every now and then flapped a fly-whisk to and fro above her head. At Miss Lee’s right elbow, in a chair set a little way behind her own, sat a very old man in dark green, gold-embroidered robes, combing a thin wispy beard with fingers like a bird’s claws. Next to him was sitting a big man whom they knew at once for the Taicoon, Chang, the bird-fancier. At the other side of Miss Lee sat a much smaller, stout man, with a brown, wrinkled face, and eyes screwed up like those of an old sailor. Some of the junk captains they had seen at last night’s supper were standing about, and some others whom they had not seen before. All watched the little procession of prisoners as they crossed the shadows on the floor, in a silence that seemed all the quieter for the chattering of men and the clicking of beads that was still going on outside. It was an odd thing, but nobody in the room seemed to matter at all beside that tiny young woman with her gold shoes and her revolver seated in the big chair. Her eyes seemed to be half-closed, yet they felt that she could see even what they were thinking.

They were placed in a row at the edge of the raised dais, immediately in front of Miss Lee. Nancy’s captain went up on the dais and joined the others behind the chair of the Taicoon, Chang.

Suddenly they saw that Miss Lee was smiling at them. They found themselves smiling back. But already her smile was gone and she was speaking quietly to the old man sitting at her elbow. Chang and the others listened. Then the old man spoke, still combing his wisp of beard. Then the little wrinkled man on Miss Lee’s left. Then Chang, who seemed to be disagreeing with what had been said. It was like watching people talking behind a window without being able to hear what they were saying. For the prisoners it was worse than that because they knew that the argument they were watching had something to do with themselves. Something was being decided about them, and they could not say a thing to help the decision one way or the other.

Miss Lee spoke again, glancing for a moment in their direction. The old man stopped combing his beard and spoke earnestly. The little man with the wrinkled eyes was nodding his head in agreement. Chang was scowling. Again Miss Lee was talking. The little man shook his head. The old man, staring straight in front of him, was twisting together two or three of the long hairs of his beard. Chang’s face changed. Suddenly he got up and crossed the dais towards the prisoners. His smile was as friendly as it had been when he and Titty had been feeding grasshoppers to his birds, but Titty, without knowing why, reached for Susan’s hand. Miss Lee said a single word. Chang suddenly lifted both hands and dropped them. He went back to his seat. He spoke to one of his captains who bowed to Miss Lee and went quickly out.

‘Our Taicoon’s agreed to something,’ whispered Roger.

The discussion, whatever it had been, was over. That part of it at least. Once more, everybody on the dais was looking at the prisoners. Suddenly Miss Lee spoke in English.

‘Who are you?’ she asked quietly.

John looked at Nancy, Nancy at John. Nancy looked straight at Miss Lee, who was watching her through narrowed eyes.

‘I am Captain Nancy Blackett,’ she said. ‘Amazon pirate when at home . . .’ She paused a moment to let that sink in.

‘Pilate?’ said Miss Lee. ‘Captain?’

‘Rather,’ said Nancy. ‘And this is Peggy Blackett, my mate.’

‘And the others?’

‘This is Captain John Walker, Mate Susan Walker, and Able-seaman Titty Walker and Roger Walker.’

‘Pilates too?’ asked Miss Lee with just the faintest hint of a smile.

‘Not exactly,’ said Nancy. ‘Explorers.’

‘How did you come here?’

‘We were all sailing round the world in the Wild Cat. She’s . . . she was a schooner belonging to Captain Flint.’

‘And Captain Flint?’ asked Miss Lee.

‘Our Uncle Jim,’ said Nancy.

‘Velly uncultured man,’ said Miss Lee, and turned to talk to the others in Chinese. ‘Go on,’ she said presently.

‘The Wild Cat caught fire,’ said Nancy. ‘Roger’s monkey . . .’

‘It wasn’t his fault,’ said Roger.

‘Monkey?’ said Miss Lee.

‘Gibber went and dropped Captain Flint’s cigar into the petrol tank,’ began Roger, but was nudged by John and shut up.

Nancy went on with the story.

‘She burnt right out and went under,’ said Nancy. ‘Then we were in our two boats . . . you’ve got them here. We saw them in the creek . . . We tried to keep together but it blew a bit hard and their lantern went out and then a junk picked up Peggy and me and Captain Flint, and Captain Flint had a bit of a row because naturally he wanted the captain to stay where he was and look for the others, but the captain wouldn’t.’

Miss Lee spoke to Chang who spoke to Nancy’s captain, who came across and pointed first to Nancy and then to Peggy. Miss Lee nodded.

‘And the others?’ she asked.

Nancy looked at John.

‘Our boat just drifted ashore,’ said John. ‘The canvas of our sea-anchor was rotten.’

Just then a new noise made itself heard above the chattering in the courtyard outside. It was Captain Flint, singing at the top of his voice. But the song was not one of the sea shanties they were accustomed to sing aboard the Wild Cat. It was something very different:

‘Columbia the gem of the Ocean,

The land of the brave and the free,

The shrine of each patriot’s devotion,

The world offers homage to thee.’

Most of them did not know what it was but John and Nancy knew very well, and knew too what Captain Flint was trying to say to them. Captain James Flint, Lord Mayor of San Francisco, was still being as American as ever he could.

The song sounded as if he were going rapidly further away.

Roger turned and bolted for the verandah. He was instantly grabbed by a guard and brought back.

‘But it’s Captain Flint,’ he said.

‘They’re taking him away,’ said Peggy.

The song was growing fainter.

‘It’s all right, Roger,’ said John. ‘He said we were to keep our heads. Don’t get excited. Nothing to be worried about.’

‘It’s all right, Roger,’ said Titty. ‘We’ll be going back too. That’s why they didn’t let us bring Polly and Gibber.’

Chang half rose from his chair, but Miss Lee stopped him by a single quiet word.

They heard the song no more.

And now the old man at Miss Lee’s elbow seemed to be suggesting questions for her to ask.

Miss Lee looked at John. ‘Were you coming here when you lost your ship?’

‘No,’ said John.

‘We jolly well would have been if we’d known,’ said Nancy.

‘Why?’ asked Miss Lee.

‘Well, pirates,’ said Nancy. ‘Who wouldn’t?’

‘Do you know where you are?’ asked Miss Lee.

‘How can we know?’ said Nancy. ‘We were shut up in the junk for a long time before we anchored, and we’ve never been in the China Seas before. We’d awfully like to know,’ she added.

Miss Lee looked closely at her, and then at John.

‘We don’t know either,’ he said. ‘We were blown a long way in the night and were close to land when the sun came up again. And then we got ashore on the island. We were nearer to it than to anything else.’

Miss Lee talked to the old man while Chang and the others listened carefully. The old man spoke again. Miss Lee asked in English:

‘Was your ship in sight of land when she was burnt?’

‘No,’ said John.

After that there was a lot more talk on the dais while the prisoners stood silent beside their guards.

Suddenly Susan burst out. ‘Please, can’t we send a telegram to say we’re all right?’

Miss Lee and the others glanced at her and then went on with their talk as if she had not spoken.

‘Not just now,’ whispered John.

Suddenly the prisoners saw that the council was over. The men were all bowing to Miss Lee. The old Chinese woman with the fly-whisk went out through a small door at the back of the room, through which they caught a glimpse of green trees and scarlet climbing flowers. Chang strode hurriedly through the room to the verandah followed by his captains. The old man with the wispy beard and the little man with the wrinkled face went slowly out talking together. The other captains followed them. Miss Lee signed to the guards and the six prisoners found themselves being stood in a row along one of the side walls.

BOOM! The big gong from over the gateway thundered once more into the air. BOOM! . . . BOOM! . . . BOOM!

‘Twenty-two times,’ whispered Roger. ‘Bet you anything.’

At the twentieth booming of the gong Miss Lee stepped down from her chair and walked slowly through the council chamber. At the twenty-first she was close to the verandah. As the throbbing of the twenty-second gong stroke died away they could see her tiny figure at the top of the steps looking down into the courtyard. There was a tremendous roar of cheering. Miss Lee came slowly back into the council chamber, smiling to herself. She said a word and the guards marched out. Miss Lee was alone with her prisoners.

‘And now,’ she said, ‘you will come with me and we will have a nice cup of tea.’

She led the way towards the small door at the back through which the old Chinese woman had disappeared. Her prisoners, too astonished to speak, followed her without a word.