At Rolling Stone, Eve found both occupation and vocation. Plus love. With her editor, Grover Lewis, a writer, too, a poet and a New Journalist, originally from Texas. (Eve’s first letter to Lewis after “The Sheik” was accepted, written care of the magazine, on a typewriter, is business formal: “Dear Mr. Lewis: . . . Enclosed is the ‘brief biography’ of myself to which you alluded. And upward, Eve Babitz.” A few months later, Eve sent Lewis another letter, also written care of the magazine, also on a typewriter, though with a cursive PS: “I yearn for you tragically.”) Says Eve, “Grover came up with the line ‘Turn on, tune in, drop out, fuck up, crawl back.’ He was great. I was almost thirty, too old to fuck around, I decided.” And when Lewis asked her to come live with him, she said yes. “I’ve always associated San Francisco with retirement, so I moved there to become a square. I thought that the move was for good, that Grover and I would get married and I’d be a grown-up. I lasted three months.”

Eve called Mirandi. Mirandi agreed to jump in her car, drive the four hundred miles up the coast, retrieve Eve. But Mirandi had a live-in boyfriend, not to mention a business, so she couldn’t jump straightaway. It would be a few days. Lucky for Eve, she just couldn’t help herself and had formed multiple romantic attachments while at Rolling Stone. Well, she was looking especially foxy, slim after an all-juice diet, and she’d been given a drop-dead new haircut—hair that was “too good for her,” as she’d describe it in a letter to Lewis—by her LACC friend Marva, now working at the salon of Gene Shacove, inspiration for Warren Beatty’s cocksman-hairdresser in Shampoo, on Rodeo Drive. (From that same letter: “[Marva and I] met in [introductory] Italian in summer school and she asked me for a match. She was trying to befriend me [during] a break while we stood outside in the arcade. . . . I told her there were matches in my purse and she opened my purse, found this . . . match box I used to keep my diaphragm in and out snapped my diaphragm and rolled down the entire length of the arcade past the other students and down the hall. ‘Go get it,’ I commanded darkly. Marva had the decency to burst into hysterics and she actually did go get it so we became friends.”)

Among those who succumbed to Eve’s charms was photographer Annie Leibovitz. Says Eve, “Joan Didion told the people at Rolling Stone to get me, so they tried, and they couldn’t. I kept dodging out of their orbit. Annie was their one hook in me. She came to my place. I had this book of Lartigue pictures—Lartigue was how I got everyone in those days—and she looked through it, and that did it. She was in my life. We were on and off for a long time.” Julian Wasser, who finally seduced Eve almost ten years after he got her naked, recalls, “As I left Eve’s apartment the next morning, I ran into Annie. She was not happy to see me—the look I got!” And it was at Annie’s apartment that Eve stayed as she waited for her sister.

It was a shame about Lewis, but there’d be other editors. As it so happens, there already was one: Seymour Lawrence, known as Sam. Lawrence, Boston-based, ran his own imprint at Delacorte, and published such luminaries as Katherine Anne Porter, Kurt Vonnegut, Richard Brautigan, and J. P. Donleavy. After reading “The Sheik” and a few of the similarly themed pieces Eve wrote for the Los Angeles Flyer, the short-lived insert section of Rolling Stone, he got in touch. She touched back, and there was an affair. Says Eve, “Sam went to Turkey and bought me a pair of gold earrings because that’s what I demanded. But then I didn’t like them.” Fortunately, lousy taste in jewelry only cooked him as a boyfriend, and she let him sign her to a book contract, which included a $1,500 advance. “I blew it all at Musso’s [Musso & Frank Grill, the oldest restaurant in Hollywood]. I ordered caramel custard for everyone, the whole place.”

Eve’s Hollywood, released in 1974, is a series of autobiographical sketches, some already published, some not, arranged more or less chronologically, and forming a loose memoir. It’s not a mature or disciplined work. Has, in fact, an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink quality to it. Certain pieces, you don’t know what they’re doing there, and most of them fail to reach the level of “The Sheik,” the high point of the collection. And yet, the riffs are marvelous: on watching the Pachucos dance the Choke in the gymnasium of Le Conte Junior High during Phys Ed;I on vamping at the bar of the Garden of Allah hotel with her friend, Sally, catching men with their jailbait; on eating taquitos on Olvera Street, two for forty cents, forty-five cents if you wanted a second helping of sauce and a paper plate, which you did. And the book, overstuffed as it is, never seems soft or flabby, but rather baby-fat voluptuous, the extra weight appealing, giving you something to grab on to, to squeeze, to pinch.

If Eve’s Hollywood has a flaw, non-niggling, I mean—every so often you’ll notice a slight strain in the prose, a bit of grammatical sloppiness, a questionable word choice—it’s related to identity: L.A.’s and Eve’s, one and the same in Eve’s mind. In Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem is a piece called “Notes of a Native Daughter,” which Didion, who grew up in Sacramento, graduated from Berkeley, lived and worked in Hollywood when Eve knew her best, was. But it was in New York that Didion established herself both professionally (her first job was at Vogue) and personally (there she met her husband, John Gregory Dunne, from Hartford, Connecticut, the son of a surgeon and a member of Princeton’s class of ’54). She was a Westerner, certainly, yet a Westerner who was at home in the East, approved of by the East, part of the East in all the ways that mattered, and it was therefore okay to take her seriously. In other words, she was as much a prodigal daughter as she was a native.

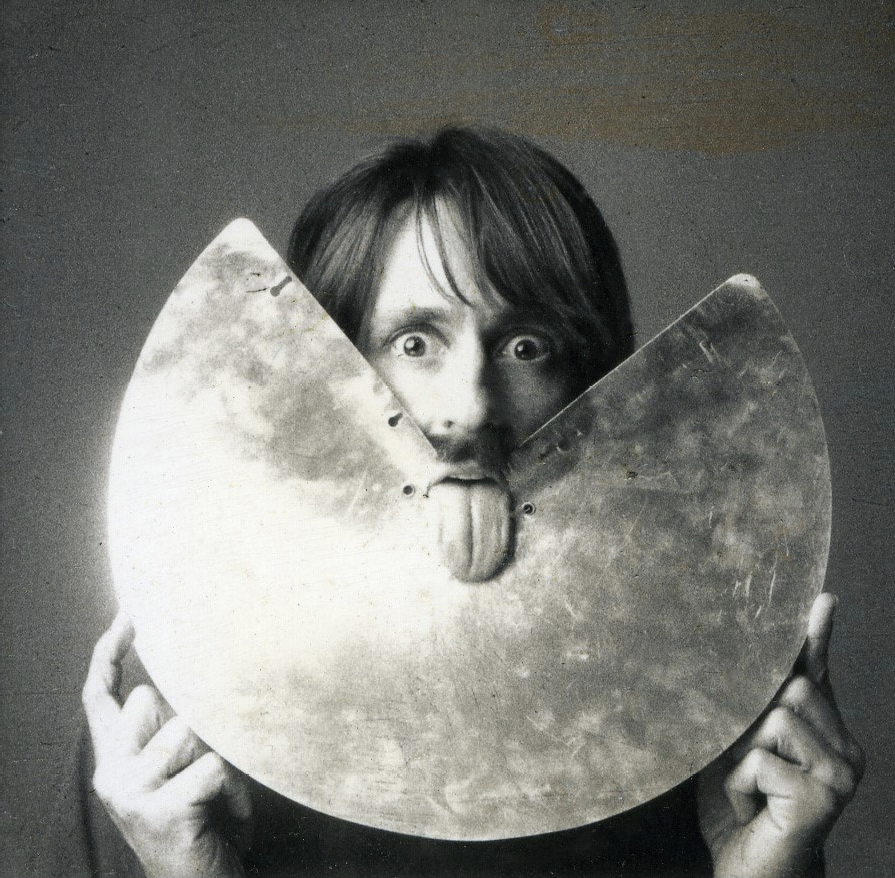

Eve, by contrast, was L.A. from the top of her (often) platinum head to the tips of her (always) painted toes. She was born and raised there, obviously. Hollywood High was the extent of her formal education, not counting the semester or so’s worth of classes she daydreamed her way through at LACC. And, apart from those three brief stints—in Europe, New York, and San Francisco—all served prior to her thirtieth birthday, she never left. Moreover, she declared her allegiance to L.A. before she declared anything else, before she declared anything period. The book’s cover is a photo taken by Annie Leibovitz: Eve in a black bikini and white boa, face in profile, breasts straight on, almost 3-D. Her appeal is as immense, as flagrant, as no-brainer as that of L.A. itself. She’s a true native daughter.

Eve Babitz, 1972

Little surprise then that she took L.A. personally. And the condescending attitude toward it adopted by the rest of the country, New York especially, galled. (Eve will defend her city as she would never defend herself, but, of course, that’s what she’s really doing when she squares off against those “travel[ing] to Los Angeles from more civilized spots,” as she sarcastically refers to the snooty out-of-towners, the “stupid asshole creep[s]” and “provincial dopes”—she gets mad enough, and sarcasm goes out the window—who miss the “pink sunsets” and the “sk[ies] of rain-swept blue” and the “true secrets of Los Angeles [that] flourish everywhere” because they’re so determined to believe that something with obvious superficial charms cannot also have subtle deep ones. She fumes, “It’s perfectly all right [for them] to say, ‘Los Angeles is garish’ . . . as they sit beneath the arbors and pour themselves another glass of wine though it’s already 3 p.m. and they should be getting back to the studio to earn their money.”) As a matter of fact, she was alluding to that classic put-down of L.A.—“cultural wasteland”—as well as to Didion, with the title of her opening piece, “Daughters of the Wasteland,” refuting the charge simply by listing the people who walked through the front door of her childhood home: Stravinsky, Herrmann, Schoenberg, et al.

So Eve’s parents conferred cultural legitimacy upon L.A. Who, though, would confer it upon Eve? She could’ve conferred it upon herself, and easily, sheerly through the force and originality of her voice and sensibility and observations. Only she didn’t trust these things yet, believe they were sufficient to compel attention. Which is why the skimpy bathing suit, and the cleavage deeper than Bronson Canyon. Which is also why the name-dropping, so out-of-control compulsive it’s practically a form of Tourette’s.

Before even the table of contents is the dedication page, or, I should say, pages, eight of them in my first-edition copy. Eve thanks the greats in her life—“And to Joseph Cornell. A Real Artist . . . And to Steve Martin, the car”—the greats formerly in her life—“And to Marcel Duchamp who beat me at his own game . . . And to Jim Morrison running guns on Rimbaud’s footsteps”—the greats she wished were in her life—“And to Orson Welles, the light of my life . . . And to Marcel Proust”—along with a few intriguing non-greats—“And to Mr. Major, I’m sorry I turned out this way . . . And to the one whose wife would get furious if I so much as put his initials in.” The style is half Oscar-acceptance-speech, half yearbook-inscription-ese, all those inside jokes: Joseph Cornell was another pen pal of Eve’s (“I wrote him a letter after I went to that show in New York with Carol. He wrote me back asking for a pinup picture. I knew what he meant but I couldn’t give him one. I loved him too much. I just wanted to be his fan”); Steve Martin bought her a VW Bug when they were together (“Linda Ronstadt was his girlfriend and I was his girlfriend and we were both doing him wrong!”); Mr. Major is Harry Major, Eve’s English teacher at Hollywood High (“Poor Mr. Major”);II and the guy with the unforgiving spouse is Tom Dowd, a renowned producer and engineer for Atlantic Records (“Tom and I used to go to a place on the Sunset Strip called Gino’s. It’s where people took people they were having affairs with. You could order weird things like venison”).

The dedication is completely over-the-top, and it tells you that Eve, at this stage, is unsure of herself, the implicit message being that if her famous friends think she’s all right, so should you. And insecurity is the reason Eve’s Hollywood takes a while to get going. It’s not until nearly the one-quarter mark, with “The Choke,” the story about the sexy Pachucos, that Eve stops trying to throw stardust in the reader’s eyes, dazzle or blind. She breaks out of Sol and Mae’s social circle, and her own—vicious circles, they had become—to talk about what she sees, the world around her. The pace and interest pick up immediately.

But again, this flaw, non-niggling though it is, isn’t damaging, not nearly as much as it should be, at least. It’s almost the reverse. It gives the book—and I know how peculiar this sounds, I’m fully aware—a quality similar to the one found in Marilyn Monroe’s smile. When Monroe smiled, her upper lip quivered slightly because she was trying to lower it to cover the gums she believed over-large. And this quiver, a flaw, or rather an attempt to mask a flaw, or rather an attempt to mask an imaginary flaw, is, I think, the source of the smile’s special power, what saves it from being merely pretty, blandly, boringly perfect, makes it instead unsettling, as poignant as it is entrancing, and totally unforgettable.

Eve’s Hollywood, good as it is, however, was still in the promising category. That promise would be fulfilled with her next book.

The publication of Eve’s Hollywood went mostly unnoticed by critics—the all-mighty New York Times declined to weigh in. And it didn’t exactly fly off shelves either. Says Eve, “It sold, like, two copies. I mean, nobody in L.A. read it. Well, except for Larry Dietz.” Lawrence Dietz, a writer and editor, someone with whom Eve had a nodding acquaintance from Barney’s, sized up the book for the L.A. Times. In the review, he cast himself as the stern yet loving schoolmaster; Eve as the naughty little girl in need of a spanking. Index finger wagging, he chided her for not taking greater care to cultivate her gifts (“To deny the full range of [your] talent because you don’t want to work in developing it is not only to diminish yourself, but also all of us who could have been enriched by it”), and for failing to live up to the shining example set by Joan Didion (“Play It as It Lays—a book so cruelly accurate that it made Nathaniel West look like Shecky Greene”III). He ended with a direct address to the reader: “[Eve’s Hollywood] is a seriously flawed book, but if you don’t mind some sloppy and self-indulgent writing, you’ll be rewarded with four or five chunks of good work.” Eve was angered by the piece, though not surprised by it. “The main thing about Larry was that he was a twat.”

Still, Eve’s Hollywood, lackluster reviews and sales figures notwithstanding, changed things. No longer was Eve a groupie, in a tongue-in-cheek sense or any other, or a struggling artist and album-cover designer. She was a writer with a book to her name. Consorting with rock ’n’ roll royalty and trash—and it’s almost always one or the other—at the Troubadour bar wasn’t for her anymore, even if a photograph she took of Linda Ronstadt did make it onto the inside sleeve of Ronstadt’s Heart Like a Wheel album (Capitol Records, 1974). She needed a new hangout.

Sticking to West Hollywood and Santa Monica Boulevard but moving a few blocks east, Eve found a recently opened restaurant, Ports. In a January 7, 1975, letter to Grover Lewis and his wife, Rae, she wrote, “I have so entangled my life with Ports that they no longer bother to charge me for food or drink and I’m interior decorating the new room and otherwise inflicting my personality on the place. It’s like a salon, just what I’ve always wanted.”

Ports was run by Micaela Livingston and her husband, Jock, an intermittent actor (his best-known role was as Alexander Woollcott in the 1968 Julie Andrews turkey of a Gertrude Lawrence biopic, Star!), who lost his temper when he was drunk, which was most of the time, regularly giving customers the heave-ho for offenses both real and imagined, occasionally choking the help. Says Eve’s friend, British-born L.A.-based designer Paul Fortune, “L.A. then was still a small town, the same one hundred people everywhere you went. It wasn’t groovy, that hadn’t happened yet. It was like this great, weird blank slate—you could write yourself into the story. And even though it was the seventies, it was also still the forties. The old cars were there, the old buildings, the rain-slicked streets out of Raymond Chandler. Ports harkened back to forties Hollywood. It was erratic. It was personal. It was strange. It had real soul.”

Ports didn’t care whether you liked it or not, doubtless the reason it inspired such fanatic devotion, from famous people in particular. (The chance to wait more than an hour for a table, to be given the wrong order, to get treated like nobody in the least special, was evidently irresistible to them.) Warren Beatty would bring in Julie Christie for romantic dinners. Robert Redford conducted business lunches at a booth in the back. Sculptor Claes Oldenburg ate at Ports when he was in L.A.; so did graphic designer Milton Glaser, and Italian art-house director Michelangelo Antonioni. Other habitués included actress-singer Ronee Blakley; singer-songwriter Tom Waits; the guys from the Eagles, usually separately though sometimes together; actor Ed Begley Jr.; director Francis Ford Coppola, especially after he set up his studio, Zoetrope, across the street. Steve Martin was also a regular. And Candice Bergen. And Carrie Fisher.IV

Says Eve, “Ports had this weird little library with Max Beerbohm in it. And Django Reinhardt was coming out of the speakers. I felt like it was my restaurant, that it had been made for me. I stayed in the same apartment for years because it was close to Ports. It’s where I met Michael Franks [singer-songwriter]. We were in bed and my feet got cold. I said I had Popsicle toes. That’s where the title to that song came from [“Popsicle Toes” was on Franks’s 1976 Warner Bros. album The Art of Tea, reached No. 29 on the Top 40, and has been covered by, among others, Diana Krall and the Manhattan Transfer].” Eve, a favorite customer, was given a brass plaque, hung above her preferred table. She even served food on occasion, when one of the waitresses quit or took the night off. Wrote Eve, “I loved it more than anything I’ve ever done before or since because deep down inside every woman is a waitress. The act of waitressing is a solace, it’s got everything you could ask for—confusion, panic, humility, and food.”

Though musicians and painters and actors and directors frequented Ports, most of the people for whom the restaurant was a second home were what Ed Ruscha termed “artists who do books,” i.e., writers: Colman Andrews, the food writer, who’d devote a chapter to Ports in his excellent memoir, My Usual Table: A Life in Restaurants; Michael Elias, the comedy writer (co-wrote The Jerk with Steve Martin and Carl Gottlieb); Kit Carson, the screenwriter (David Holzman’s Diary); Nick Meyer, the novelist (The Seven-Per-Cent Solution); Warren Hinckle of the muckraking political magazine Ramparts; Julia Cameron, journalist for Rolling Stone; and, when in town, Tom Wolfe, steering clear, no doubt, of the stuffed game hen in plum sauce for the sake of his white suit. Elias: “Ports was for people who were too hip for disco. It was like a club. I was there every night. You could do coke, fuck in the bathroom. There was a piano that this terrific jazz guy, Freddie Redd, used to sit at. Sometimes there’d be performance art, or someone would put on a play. Jock used to get drunk and decide he was going home. He’d toss us the keys and tell us to lock up when we were done. There really wasn’t anything else like it in L.A. When my first wife and I got divorced, it wasn’t ‘Who gets the Lakers tickets?’ It was ‘Who gets Ports?’ Eve was the queen of it all.”

And every queen must have her king.

Eve, at twenty-three, en route to a wedding at which she’d been engaged to the groom and the best man (“I’d broken off with both . . . because I was impatient with ordinary sunsets”), asked Mae whether Mae believed she would ever get married. Instead of giving an answer, Mae gave advice: “If you do, marry someone you don’t mind.” Trickier to follow than it sounded. At least for Eve. Not minding might have been where she started out with a guy. It sure wasn’t where she ended up, though. Besides, she was too restless, too imaginative, too wayward, too independent for connubial bliss to be anything but abject misery, as she was beginning to realize after calling it quits with Grover Lewis. She simply wasn’t cut out to be a wife, or even a girlfriend in the conventional sense. Mistress, a role that was part-time and no-strings, fantasy-based rather than reality, was far more suitable to a woman of her tastes and temperament. Still, it was with genuine regret that she decided “those songs of love were not for [her].” And, since life is as perverse as it is perplexing, that’s the precise moment she met Paul Ruscha, younger brother of Ed.

Paul: “I left Oklahoma City the summer of the Watergate hearings. I remember the exact date, June 25, 1973, because it was the half Christmas. My relationship with Larry, the man who owned the restaurant I worked at, had become unbearable after eight years. He’d started fucking his son’s friends, and they were just high school kids, and I’d had it. Ed didn’t approve of that side of me—the gay side. But he understood what I was going through in his Ed way because he’d split with his wife, Danna, the year before and was living with Samantha [Eggar, the actress]. So Ed sent for me, and I was glad of the fresh start. I worked for him as an artist’s assistant and stayed with Danna. One afternoon Danna took me to Jack’s Catch-All, a thrift store on Alvarado. That’s where I first saw Eve. She and Danna talked. After we left, Danna said, ‘I think she likes you.’ I was surprised because I didn’t think she’d even noticed me. Eve was heavy then, but I was so skinny that when I had sex with girls who were also skinny, our bones would just bang together and it hurt! So I didn’t mind heavy. Eve invited me over for dinner. Eve was friends with Léon Bing [the fashion model], who used to go out with Ed, and she called Léon and said, ‘How can I get him?’ Léon told her that I love cilantro. Actually, I hate cilantro, but Léon just remembered that I had a strong reaction to it. She made a mistake.V Eve put cilantro in the soup, in everything, so I couldn’t eat a bite. She called me the next day and said, ‘Can I have a second chance?’ I said, ‘Sure you can.’ She made me a wonderful dinner that night. And she showed me a story she’d written, and I was blown away by it. We were together from then on.”

Paul, thirty, was, same as Ed, an artist, and talented. Unlike Ed, however, who was laconic, solitary, a little aloof—a cool, cool customer—Paul was gregarious, expansive. Says Paul, “L.A. then was the Endless Party. Ed would look at me and say, ‘Don’t you ever stay home?’ When I first arrived, we went to events together often. Then I started to notice that he’d ask me if I was going to a certain party, and if I said yes, he didn’t come. I always threw myself into the action. I guess he was afraid I’d make a fool of myself and, because we were related, make a fool of him.” The isolation, the rigor—the egotism—that’s necessary to make a career out of art, where there’s no objective criteria, where you can’t look for an endorsement from the world or you undercut the authenticity of the work, where you must be obsessed, absolutely and utterly consumed, with getting something great out of yourself, was against Paul’s nature. Art became a thing he was content to do on the side. “In the early sixties I went to the Chouinard Art Institute, where Ed had gone, and began to paint. I was having so much fun that I thought I wanted to be a painter. I asked Ed’s artist friend Joe Goode about my becoming an artist, and Joe advised me to be anything but unless there was nothing else I could do better or loved to do more. Ed’s success was quite daunting. He liked that I could make art. He didn’t like that I couldn’t keep up with his rise to art stardom. He had the burning desire. I just didn’t. It’s hard being Ed’s brother sometimes, but it’s great working for him. He’s the best boss I’ve ever had, and incredibly generous.”

Also, same as Ed, Paul was a dreamboat, though a different make and model. Ed, small and compact, had the flinty, lean-faced handsomeness of a Gary Cooper or a Henry Fonda, actors who could easily play cowboys and other classic American male archetypes. Women took note. Says Eve, “Everybody threw themselves at Ed, and, when he had a couple of spare minutes, he’d reach.” For starlets, most often. Eggar, Michelle Phillips, Lauren Hutton were all girlfriends at one time or another. Paul was taller than Ed, and rangier, with a considerably wilder dress sense: monkey-fur coats, contact lenses that turned his brown eyes silver, and a mustache that was part porn star, part Salvador Dalí. Wrote Eve, “It seemed to me that [Paul] was possessed by the Angel of Sex. . . . He was approaching my ideal in record time and even [Brian Hutton] was beginning to pale by comparison. . . . When he first took off his clothes in front of me and I saw him standing there, there—in my very own bedroom . . . [it] caused me to gasp.”

Yet it wasn’t just Paul’s looks that Eve responded to, it was also his style—calm, courtly, decorous—which happened to be the exact opposite of her own. She wrote, “[Paul was] always trying to smooth things over and [I was] always trying to rumple them up. . . . Perhaps [he], in the beginning, looked upon me as a challenge. Maybe he felt he could show me the path to . . . gentle society.” He couldn’t, of course, but Eve appreciated the effort. Says Paul, “Eve was destructive, to herself more than anyone else. That only made me want to save her. I felt she did better when she was with me, that she was less agitated. I was forever apologizing for her. I remember a guy came up to her at a party and told her that she was his favorite writer, and she just looked at him and said, ‘Beat it.’ ” If bad behavior was so loathsome to Paul, though, why would he be with someone who refused to behave any other way? Eve knew. “[Paul] would dry lepers’ feet with his hair; [I’d] often feared that he would leave me not for some prettier or richer person, but to perform some Christian act of atonement.” In other words, Paul was a saint. Or in different other words, Paul was a masochist.

Paul Ruscha, 1976

Which is why he and Eve, a sinner and a sadist, were matchlessly mismatched and thus a perfect match. Even the fact that her passion for him far exceeded his for her worked in their favor, like her too-muchness and his not-enoughness came to exactly the right amount. The enemy for Eve had always been boredom, and with Paul she couldn’t get bored. His ambivalent sexuality—drawn as he was as powerfully to men as to women—his ambivalence in general—drifting along as he did aimlessly, pleasantly, in a free-form, episodic way—allowed her to maintain her equilibrium by keeping her off balance. And it had the same effect on him. In his memoir Full Moon, he wrote, “[I’d] become one of those odd birds who seem to be attractive to others, but cannot commit themselves to . . . any of them.” Because without the weight of Eve’s emotionalism, her intensity, her breasts and flesh and need, you feel that Paul, so pretty, so passive, so captivatingly noncommittal and gossamer light, would have floated off into the ether, dissolved like a dream in the warm Southern California air.

And between them was an instinctive understanding and sympathy. Paul: “Eve could be wonderful in a way no one else could. I regret not saving a letter she wrote me. It was about my color blindness. In it, she described the colors, what moods went with which. It was sweet and romantic and totally Eve. Much of her chutzpah came from her blind belief in herself, and I fed into it. When we were together, she was, as I said, quite hefty. I just likened her to a masterwork odalisque by Rubens. Friends would ask me how I could stay with her when she was obviously so crazy, but I felt she was as exotic as she thought I was. She certainly had the most interesting mind I was ever privy to. And Ed very much approved of her. He loved her for her notoriety, for the Duchamp photo, for the men, for the fact that she wrote as well as she did. Eve was my main squeeze—that’s what she liked me to call her—but I was hot on the market then and seeing other people. So was she. Annie was around a lot. Eve used to say that Annie was the son John [Gregory Dunne] and Joan [Didion] never had. And Eve kept old boyfriends in her life. Every few days, one would call, and she’d talk to him about his new girlfriend or wife, about books or movies or restaurants. I loved being the guy in her bed listening to her laughing with former beaux. She’d walk around the tiny apartment, tripping over the clutter or her cats, Mario and Sympathy, tangling the hell out of the phone cord. After she hung up, I’d untangle it for her.”

Eve and Paul found a way of being together that largely involved being apart. “I spent the night at Eve’s once or twice a week, two or three times when we were really lovey-dovey. I could never have lived with her, couldn’t have stood the mess. There’d be cat fur—cat fur!—in her food. She was a great cook, though.” And not only was Paul able to give Eve both the intimacy and distance she required as a woman, but also as a woman who wrote. “On Eve’s door was a sign that said, ‘Don’t knock unless you’ve called first.’ She always told me she liked me because I knew when to go home. What would usually happen is, we’d go out the night before, and then we’d come back to her place and fuck and fall asleep. In the morning, she’d drop two scoops of coffee in a pan of boiling water and bang the spoon against the side of the pan loudly so I’d wake up. Then she’d thrust the cup of coffee at me and say, ‘Okay, I’m going to start writing now.’ And I’d say, ‘Okay, okay, I’m leaving.’ Then she’d say, ‘Would you read something first?’ And she’d go over to her typewriter and grab some pages. I’d read them, and she’d ask my opinion. If she liked what I had to say, she’d let me stay a little longer. If she didn’t, she’d kick me out. And the next time I came over, she’d show me the piece or the chapter again and ask my opinion. So I ended up reading everything she wrote nine or ten times.”

I’d begun linking Paul and Mae in my mind long before I realized that’s what I was doing. The writer Caroline Thompson, close with Eve since the late seventies, was the first to mention Paul. “Have you met Paul yet?” she asked, almost in a whisper, as if she were sharing with me a thrilling secret. “Paul’s wonderful.” The more people I interviewed, the more times I had to lean in, cock my ear, as their voices dropped to an enchanted hush. “Oh, Paul? Paul’s wonderful.” Their voices would do the same thing when Mae’s name came up, and there was that word wonderful again. As in “It’s too bad you didn’t get to meet Mae [Mae died in 2003]. You’d have loved her. She was just wonderful.”

I contacted Paul shortly after my conversation with Thompson and found him to be wonderful indeed. So wonderful, in fact, that I decided then and there to make him my friend. A few weeks later, I was on the phone with my brother, telling him what I’d been up to. I heard my voice go small and soft when I said Paul’s name, and that’s the moment I explicitly made the connection: Paul was Mae; Mae was Paul. (Incidentally, Mae made this connection herself. Says Laurie, “When Evie started going with Paul, bringing him around, Mae said, ‘I thought it was supposed to be sons who married their mothers.’ ”) Like Mae, Paul was the quintessence of loveliness and charm, with the manners of someone from a part of the country nowhere near a coast. And, like Mae, Paul was an artist who served a more dominant artist and served that artist superlatively. In Paul’s case, Ed and Eve—double duty.

So if Paul is Mae, who does that make Eve? Why, Sol, of course. Laurie: “My mother, Tiby, didn’t marry until she was twenty-five, which was late in those days. She said the reason was that she never found a man as amazing as her brother Sol. If we had any religion in my family, it was that Sol was a fucking genius, the smartest guy in the world. There was a time where I sat down and thought, Gee, maybe that wasn’t true. But I couldn’t face the possibility. I still can’t. He formed us all. He had this magnificent collection of 78s, and Eve and Mirandi and I used to listen to his Bessie Smith records, the dirty ones, on the sly. But then we couldn’t anymore because we got caught when Eve sat on Empty Bed Blues and broke it in half. And Mae started drawing, became an artist, because Sol told her she could be. His power and judgment ruled everything. I don’t say I started going with Art [Pepper, famed jazz alto saxophonist and junkie] because I knew it would make a splash. But it did. I can’t think of anyone Sol would have thought was cooler or hipper than Art Pepper. Getting Sol’s attention wasn’t easy. Evie would say something clever. That got his attention. She started writing, and the writing was good. That got his attention, too. Besides, she demanded his attention. If it meant she had to bite him on the leg, which is what she did when she was four—burst into his studio when he was practicing, which none of us ever dared do, and bit him on the calf—then so be it. Mirandi was in a state of despair because she could never get his attention. Sol was sitting in the house talking to a friend, and Mirandi—adult Mirandi—walked through the door, and he said, ‘Oh, that’s my daughter, but she’s not the one.’ What a thing to say! Do you think Mirandi ever forgot that? Listen, I’m sure Evie, smart a kid as she was, looked at Sol and looked at Mae, saw Mae running around, doing everything to make Sol happy, and thought, Yeah, he’s the one I want to be.”

Another important person came into Eve’s life during this period, Erica Spellman, a hotshot agent from ICM in New York who represented Fran Lebowitz and Hunter S. Thompson. Spellman, now Spellman-Silverman: “Kit Carson introduced me to Eve. When I got to town, he said, ‘There’s someone you’ve got to meet.’ Eve and I had lunch—at Ports, naturally. She gave me a copy of Eve’s Hollywood. I read it. I loved it. I called my sister, Vicky [Victoria Wilson, editor at Knopf]. I said, ‘Vicky, you’re not going to believe this woman I met. She’s fabulous and she’s going to write this amazing book for you and it’ll be essays.’ And Vicky said, ‘Okay.’ You could do that in those days, call someone up and say, ‘Here’s this person, let’s do something,’ and they would. I never considered calling anyone other than Vicky. Knopf has always been the best publisher, and Eve needed credibility. She was seen as this sexy girl who somehow got Seymour Lawrence to publish her book. A lot of people knew she’d slept with him, which wasn’t helping. I wanted her to be thought of as a serious writer, not just as this strange creature floating around L.A. Eve and Vicky really loved each other, and I think Eve felt, for the first time, like she had protection—me and Vicky, ICM and Knopf. What I did was call her up every single Monday morning for a year. ‘How’s the book coming?’ I’d say. She sent in pages to Vicky, and Vicky helped her get those pages into shape. And that’s how Vicky and I dragged Slow Days, Fast Company out of her.”

I. A precise definition of Pachuco is hard to come by. A hoodlum of Mexican extraction, is my best guess. As for the Choke, here’s Eve’s definition: “a completely Apache, deadly version of the jitterbug.” How’s that for precise?

II. After learning who Mr. Major was to Eve, I attempted to track him down on the off chance that he was still alive, could describe for me Eve as a student. He wasn’t, but I’d only just missed him. He died on February 10, 2014, at the age of eighty-two. He was murdered by an ex-con named Scott Kratlin in his apartment on North Vista Street, only a handful of blocks from Hollywood High. Kratlin and Major had struck up a correspondence while Kratlin was serving a twenty-one-year sentence at the Marcy Correctional Facility in Oneida County, New York, for manslaughter. Major promised to give Kratlin a place to stay when Kratlin was released in exchange for sex. (Major had extended a similar offer to hundreds of state and federal prisoners all over the country.) Kratlin lived with Major for ten days, then moved out, though not before strangling Major and bashing in his head. Poor Mr. Major indeed.

III. Dietz misspelled Nathanael West’s first name. Some schoolmaster.

IV. In 1976, Eve and her old Capitol Records contact, graphic designer John Van Hamersveld, got loaded together, hatched a harebrained scheme: the L.A. Manifesto, an underground paper. In the first issue were, among other contributions, songs by the Eagles, poems by Ronee Blakley, and stories by Steve Martin (his first). It was supposed to be a monthly thing, but Eve and John lost steam and/or interest, and so the first issue became the only. I stumbled across a copy early in my research and used it the way I used the Eve’s Hollywood dedication—as a combination Rosetta stone and little black book. All the people in it had, presumably, once been important to Eve and were thus potential interview subjects. Since Carrie Fisher was featured twice, a poem and a story, I figured I’d start with her. Fisher, though, according to her publicist, had no recollection of Eve. I picked up Fisher’s then-still-new memoir, Wishful Drinking, hoping Eve would be in it. She wasn’t. A transcript of the outgoing message on Fisher’s voice mail, however, was. “Hello and welcome to Carrie’s voice mail. Due to recent electroconvulsive therapy, please pay close attention to the following options. Leave your name, number, and a brief history as to how Carrie knows you, and she’ll get back to you if this jogs what’s left of her memory. Thank you for calling and have a great day.” I dialed Eve, extracted from her what history I could, and it wasn’t much (Eve’s drug consumption increased in the mid-to-late seventies, and so her memory of this period is spotty)—“Carrie was a Ports person, and Ports was dark, so it was great if you were someone who wore hats, and I was, and so was Carrie”—relayed it to the publicist, except it failed to jog anything. A promising lead turned dead end. No big deal, I simply backed out, moved on. The only reason this anecdote even rates a mention is because it, more than any other, captures what I so often felt was my role in Eve Babitz’s life: half the nameless narrator, that would-be biographer and “publishing scoundrel” in Henry James’s The Aspern Papers, half an extra in an Abbott and Costello routine.

V. Eve does not believe that Léon made a mistake. She believes that what Léon made was mischief, and is still, to this day, mad about it.