Chapter 3

Ad Man

Andy and Philip moved into a small, drab apartment in the East Village of New York City. They visited the art directors at magazines and advertising agencies and showed their pictures from college. Art directors decide what kind of pictures go into magazine articles or the ads for different products. Andy’s drawings were exactly the type of work that the art directors were looking for. He quickly got jobs from them.

There was plenty of work in the advertising and magazine business in the late 1940s and the 1950s. World War II was over, and soldiers came back from the war ready to return to work. They bought new cars and houses and furniture. Scientists who had been developing weapons for the war now created things that made life easier and more fun, like frozen dinners, modern stoves, and better refrigerators. Everyone seemed to be spending more money. Artists like Andy helped show them what to buy.

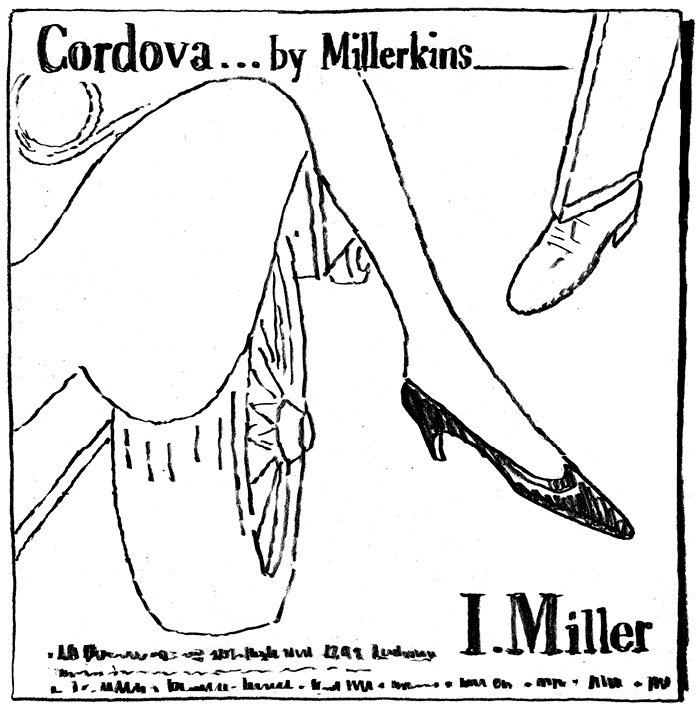

Andy was known for his “blotted line” drawings. Instead of even, flowing lines, his pictures were a mix of thin and thick lines, with dashes of empty space between them. His drawings were energetic and happy, as if the lines were jumping across the page. Art directors thought that it was the right style for the modern, cheerful 1950s, especially for fashion. Andy became famous for illustrating shoe ads for a company named I. Miller. His shoe drawings were splashed all over the huge ads the company placed in the Sunday newspapers.

By the early 1950s, Andy was known by everyone who worked in magazines or advertising. They knew him as Andy Warhol, though, not Andy Warhola. A few years earlier, a magazine he worked on mistakenly dropped the “a” and printed his name as just “Warhol.” And Andy decided to keep it that way.

Andy’s appearance changed as he made more money. He bought better clothes. He began seeing doctors to make his skin look better. But then, just when he was getting more comfortable with his physical appearance, he began to go bald. At first, he wore a hat everywhere until friends persuaded him to try a wig. He wore wigs for the rest of his life.

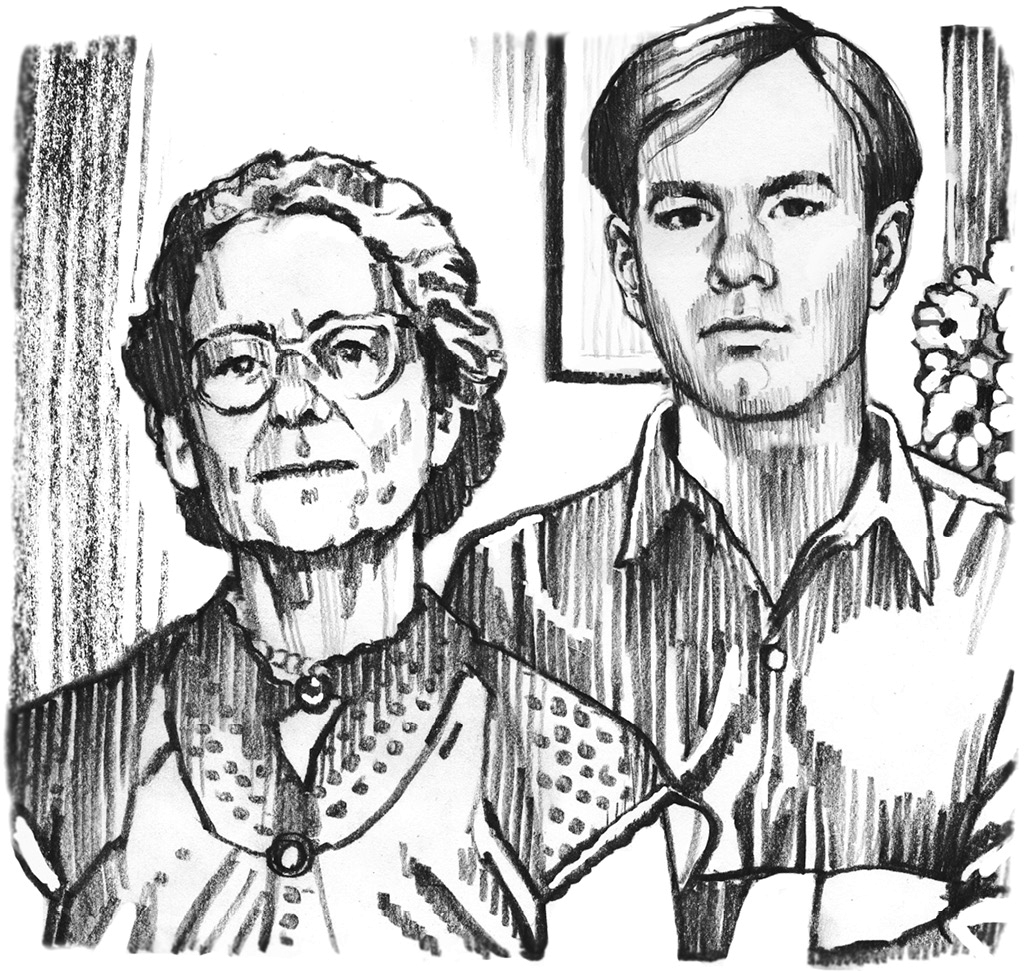

Andy’s mother, Julia, came to visit him in New York in 1952. His apartment was cold and messy. He had a cat to help catch the many mice and rats. Julia decided to move to New York to cook and clean for Andy. Over time they got more and more cats. Julia named them all Sam.

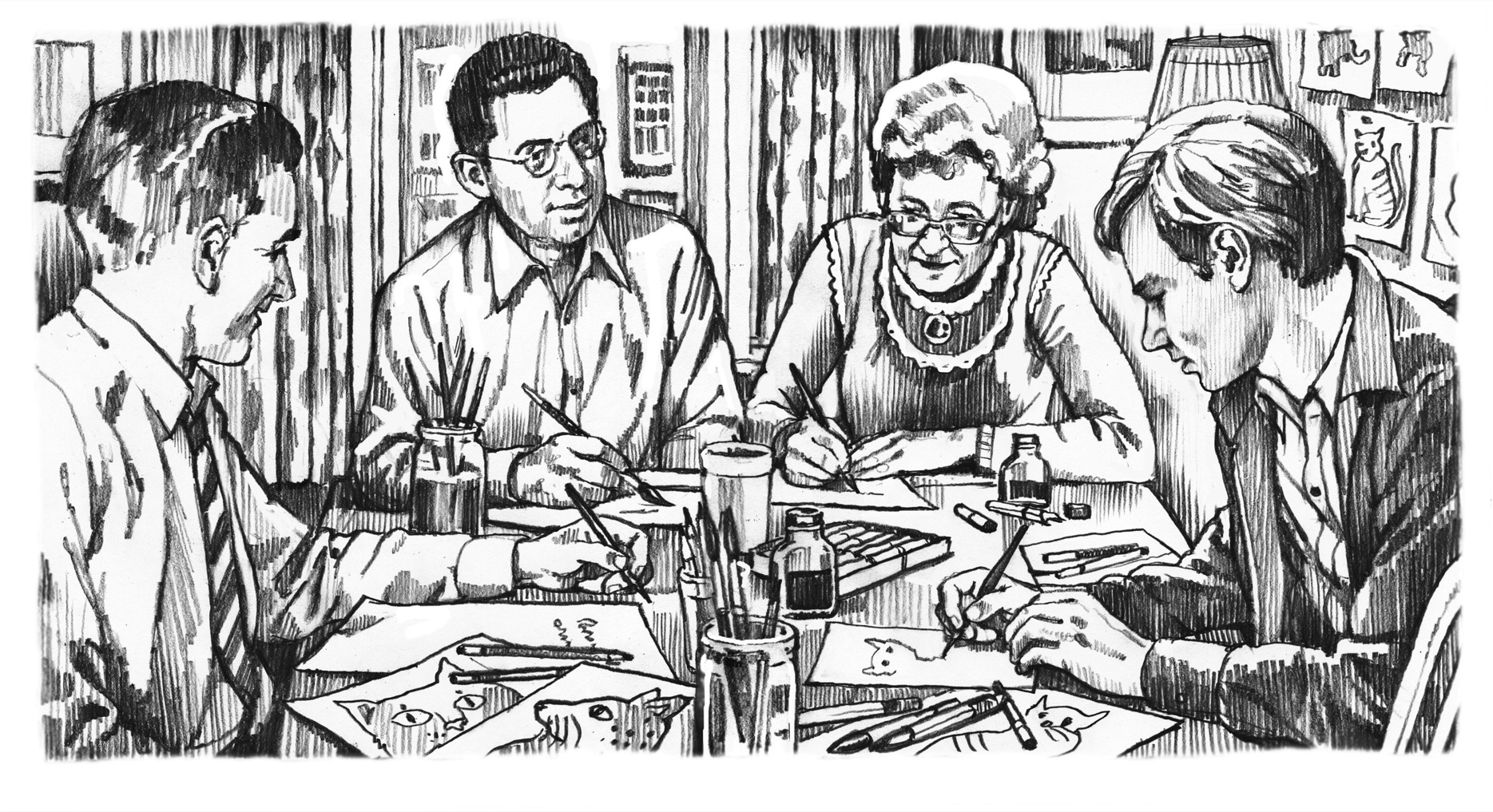

Andy often had friends help with his illustrations. Now Julia helped, too. He would gather everyone together at his apartment or a café. They would each have a special task, like adding color to the drawings. Julia wrote the words in her old-fashioned, curly handwriting. Andy could work a lot more quickly this way. He liked the idea of creating an “art factory.”

Andy had lots of friends, but not much luck in love. In the 1950s, gay people often felt it was safer to hide that they were gay. They weren’t always treated kindly. Andy didn’t care. He was sure enough of himself to be himself. However, he was shy about his looks. It was hard for him to compete with all the handsome people in New York’s gay community. He dated a few men, then fell in love with a set designer, Charles Lisanby. They even went on an around-the-world trip together in 1956, but drifted apart after they returned. Andy did not have an easy time finding love.

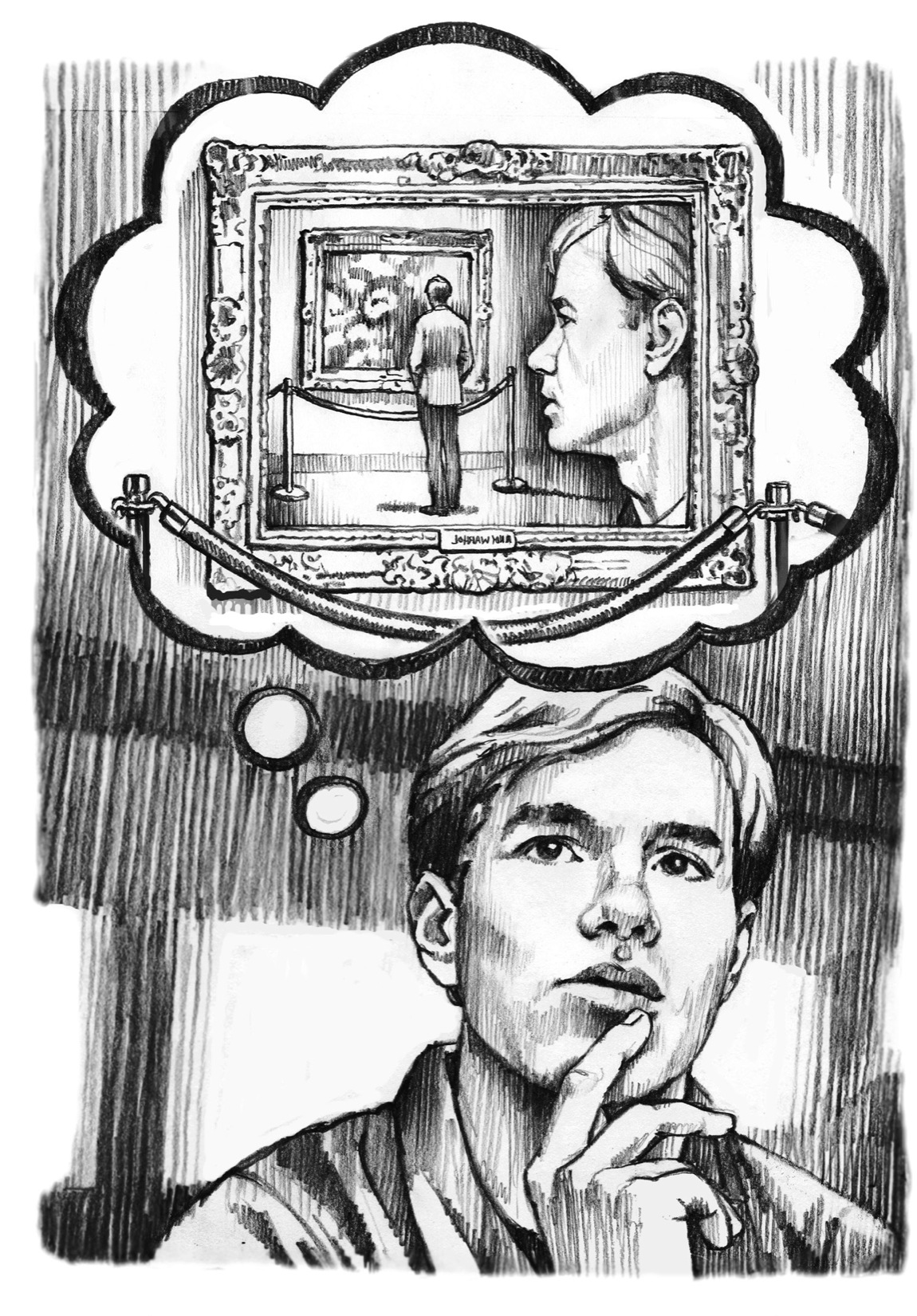

By the mid-1950s, Andy had a lot to be proud of. The illustrations he drew for ads won awards from the Art Directors Club and the American Institute of Graphic Arts. He was making plenty of money. But something was missing. Andy dreamed of being an artist whose pictures were sold in art galleries and displayed in museums. He wanted his name to be recognized by the whole world, not just by art directors in New York City.

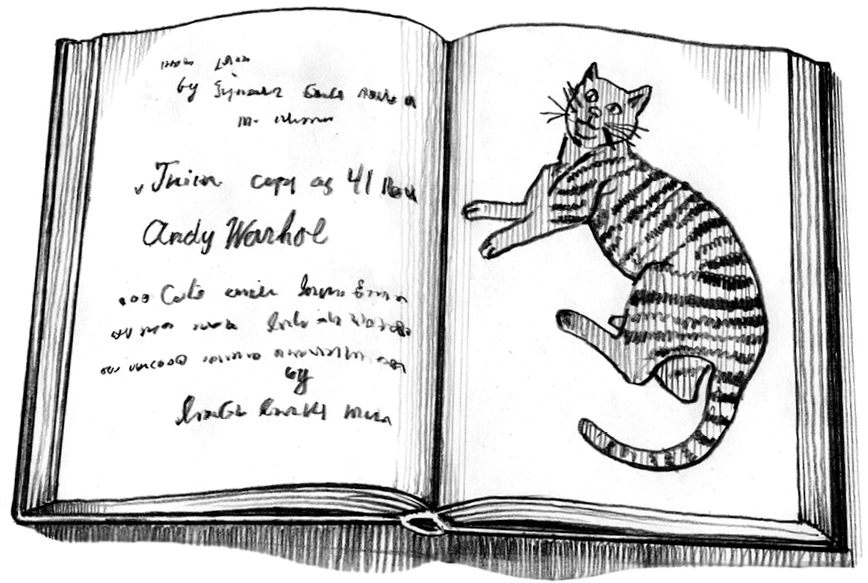

Andy tried to get more people to see his drawings. He showed some of them in small art galleries. He worked with friends to create books of his drawings. He and Julia created a book of cat pictures called 25 Cats Name Sam and One Blue Pussy. Andy published the books himself and sold them in gift shops. Everyone thought Andy’s drawings were cute, but they still just thought of him as an advertising illustrator. In a 1958 Who’s Who–type book about people living and working in New York City, Andy’s name wasn’t listed under “Artists.” It was listed under “Business.”

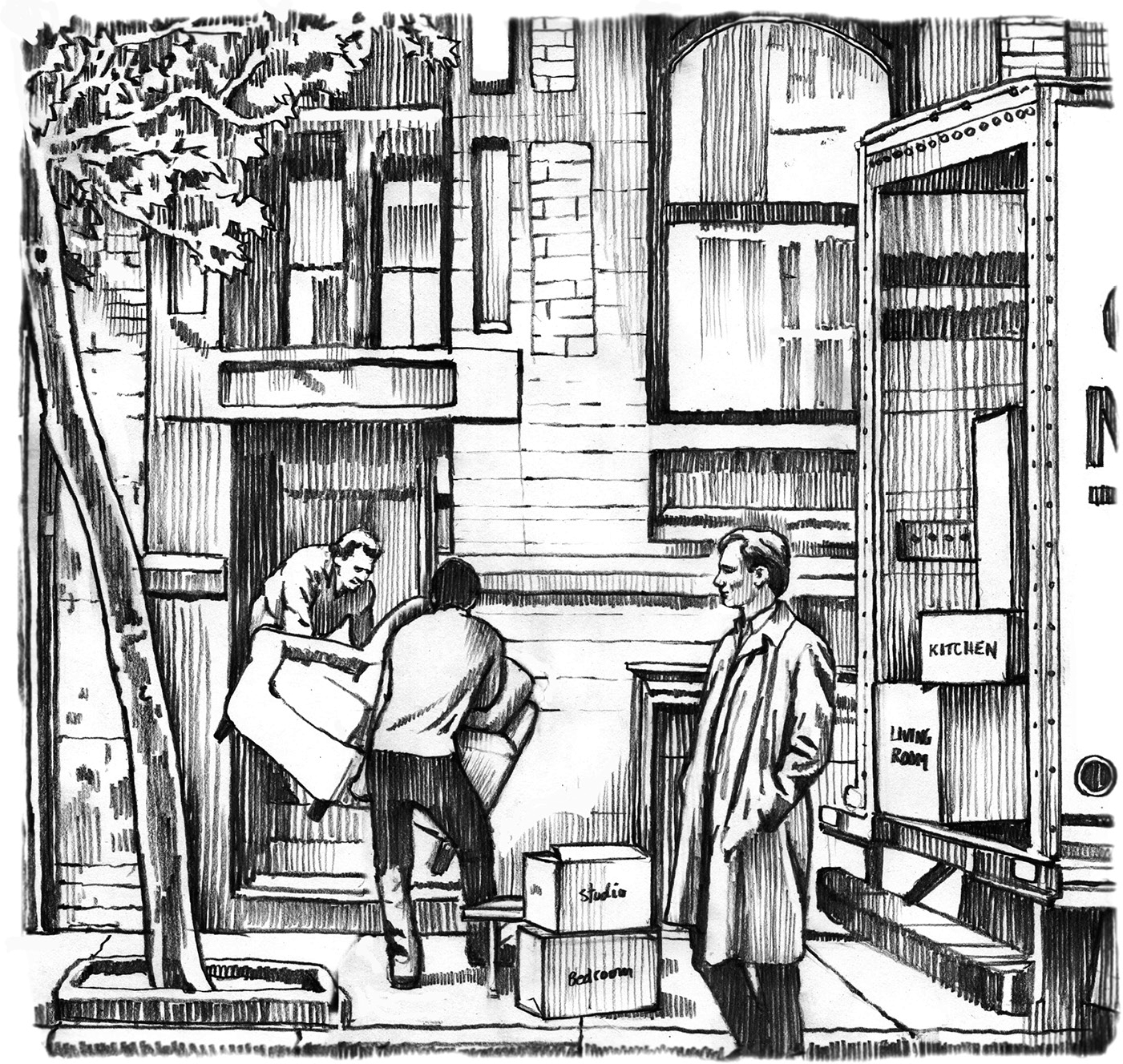

Andy made a decision. He would still work in advertising, but he was going to spend more time trying to become a serious artist. In 1960, he bought a town house on Lexington Avenue with room for an art studio. His brothers came from Pittsburgh to help move Andy and Julia and all their cats and things to the new house. It was time for a big change.