Chapter 4

Breaking In

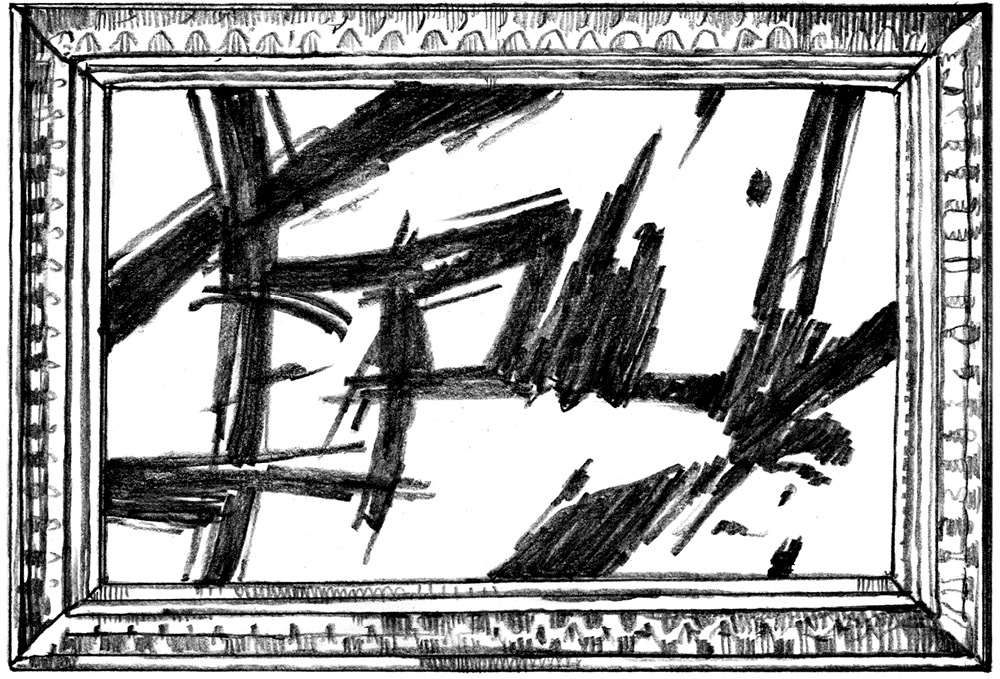

The art world was also changing. Since the 1940s, the most important paintings had been in a style called “Abstract Expressionism.” They were made up of streaks, splatters, and blobs of paint, or big patches of color. These artists were “expressing” themselves through color and texture on the canvas.

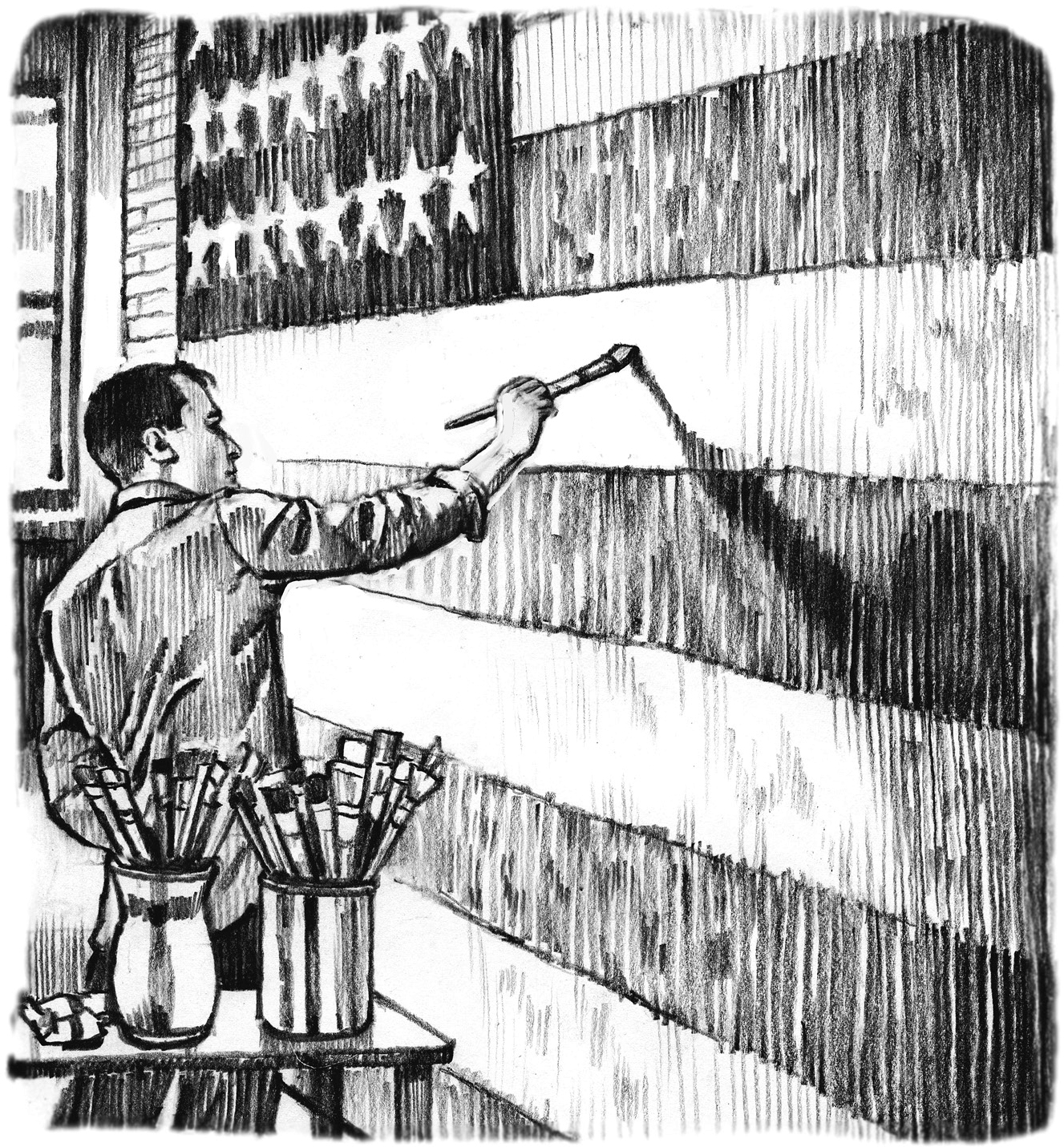

By the late 1950s, some artists were breaking away from Abstract Expressionism. Jasper Johns painted pictures of familiar things like American flags, numbers, and bull’s-eye targets. Robert Rauschenberg created works that combined painting, photographs, and actual objects like nails, rocks, and pieces of clothing.

Andy had no interest in expressing himself through streaks of color and blobs of paint. Painting real, everyday things—like in the artwork by Rauschenberg and Johns—made more sense to him. But he didn’t want to copy other artists. He wanted to do something new and different.

He painted the front pages of newspapers, Coke bottles, and comic-strip characters like Superman and Popeye. But Andy worried that people might not think these kinds of paintings were important works of art. Although a department store put his comic-book paintings in their window display, he couldn’t find an art gallery to give him his own show.

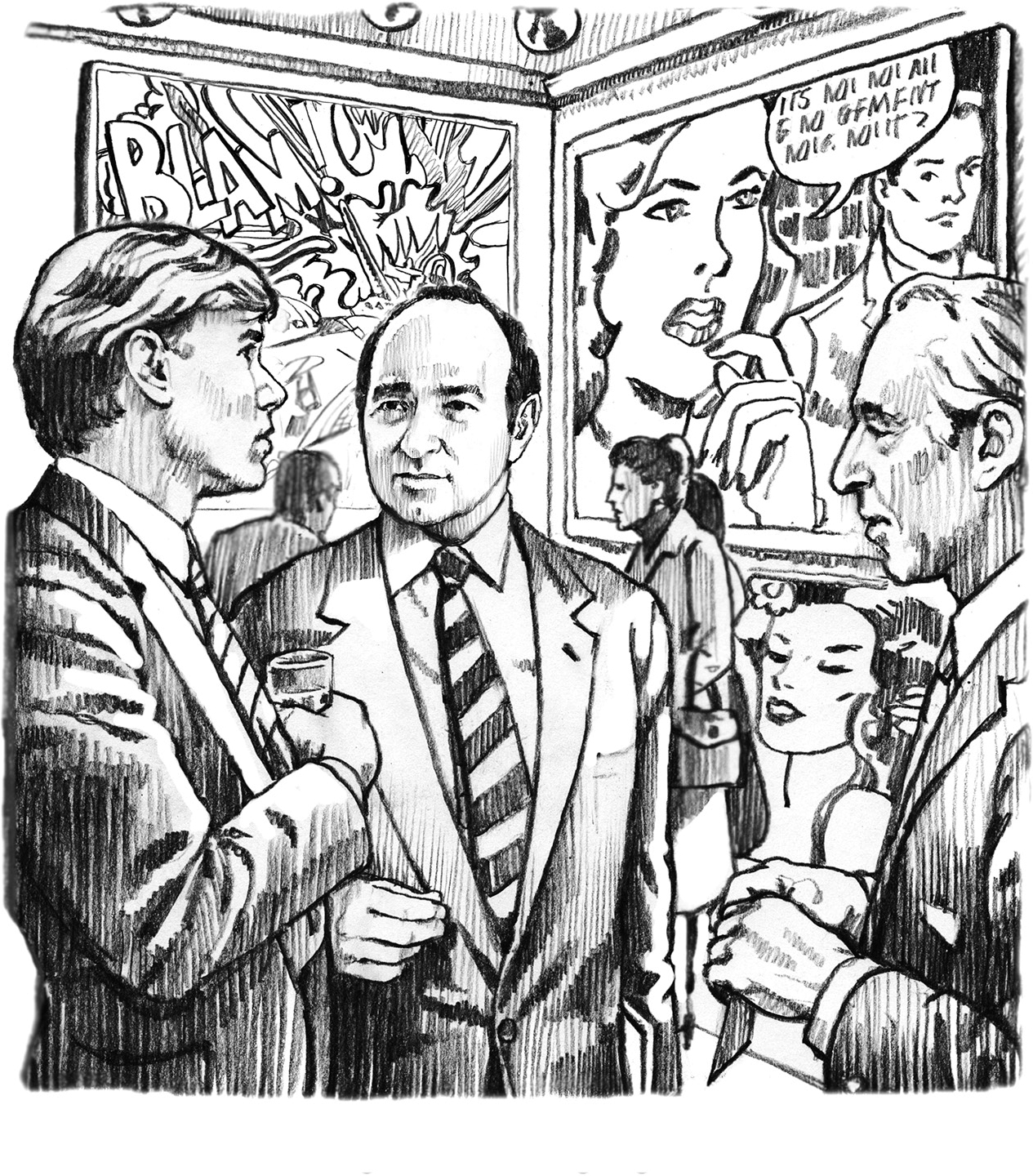

One day, Andy and a friend went to the famous Leo Castelli Gallery to look at paintings. Andy desperately wanted to have a show there. Ivan Karp, the associate director of the gallery, showed them some new pictures by an artist named Roy Lichtenstein. They were all based on comic-book illustrations. They didn’t have any of the “artistic” touches Andy had put on his pictures, though. They were painted with bold, clean lines. They looked exactly like the drawings in a real comic book. Andy’s heart sank. He and Lichtenstein were painting the same type of thing! But Lichtenstein was doing it better. No one would care about Andy’s comic-book paintings now.

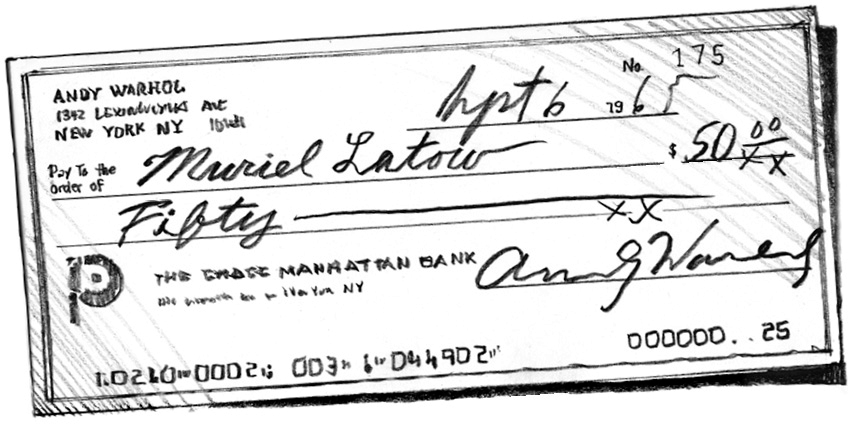

Andy always liked to talk about what he was painting and what he should paint. In November 1961, Andy invited his friend Muriel Latow to his house. She owned a small art gallery, and Andy thought she always had good ideas.

“Just tell me what to paint,” Andy said.

“That’ll cost you fifty dollars,” Muriel said.

Andy didn’t really want to pay Muriel, but was anxious for new ideas. He wrote her a check for fifty dollars.

Muriel’s idea was for Andy to paint something people see every day, like a can of soup. How about really big paintings of Campbell’s soup cans?

Andy loved the idea. Everyone knew what the red-and-white Campbell’s soup label looked like. His own mother often made him Campbell’s soup for lunch.

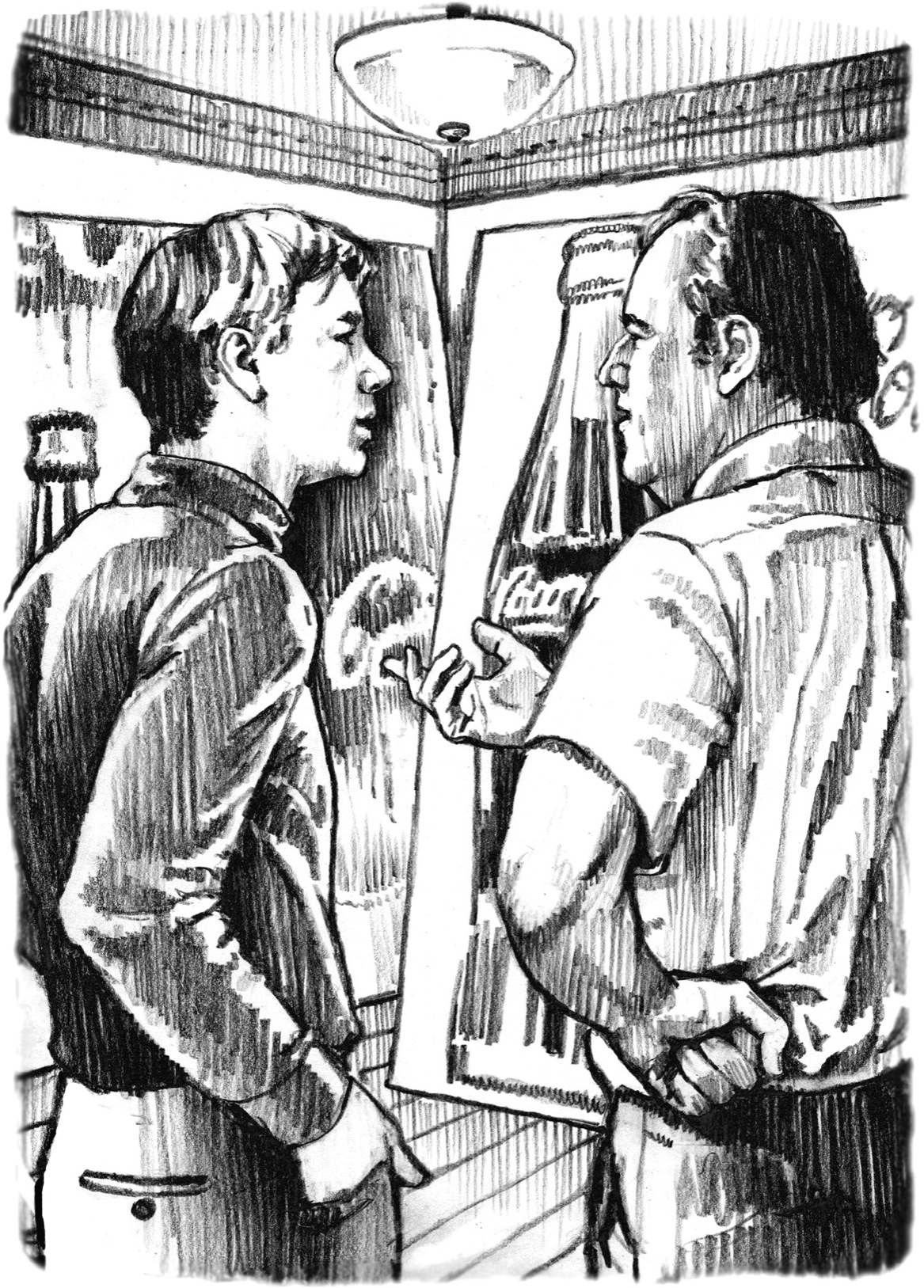

But he knew he couldn’t paint the soup cans in his old comic-book style. In early 1962, Andy asked his friend Emile de Antonio to look at some paintings. He showed “De” two pictures of Coke bottles. One had paint drips and sketchy lines like the Abstract Expressionists used. The other was just a simple painting of the bottle, done with smooth, clear lines. De immediately told him to forget the drips and blobs. The clean painting was bold and modern. Andy agreed. This was his new style.

Andy went to work painting his soup cans. Each painting was a different flavor of soup. He didn’t even try to make them look realistic. Instead, it looked like he was painting an illustration of a soup can label!

In December, Irving Blum, an art dealer from California, came to New York. He had met Andy before but hadn’t really liked any of his work. He liked the soup cans, though. He asked Andy to show them at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in the summer of 1962. Andy was delighted.