Chapter 6

Factory Life

Andy had one assistant who helped him with advertising projects, and a new assistant, Gerard Malanga, who had silk-screening experience. With his assistants and Julia, Andy’s town house was becoming crowded. In late 1963, he found a new studio space to rent in a building on East 47th Street that used to be a hat factory.

Andy moved his studio there in January 1964. He asked his friend Billy Linich (who later became known as “Billy Name”) to cover the walls in silver paint and aluminum foil. He thought silver was a very modern color. It reminded him of the suits worn by astronauts. It took Billy almost three months to cover the entire space in silver. He spent so much time working there that he moved into a small corner of the studio and lived there for the rest of the decade.

Billy was a lighting designer who lived in New York’s East Village. Andy loved to go out, and Gerard knew how to find all kinds of interesting people and events in the busy East Village art scene. The East Village was different from the Upper East Side, where all the important art galleries were and where wealthy art buyers lived. The East Village was filled with old buildings that weren’t in very good shape. Struggling artists could afford to live there.

Andy and Gerard went to modern dance shows, poetry readings in cafés, and rock concerts. Andy was especially fascinated by the “underground filmmakers,” who showed their short, experimental films on the walls of people’s apartments.

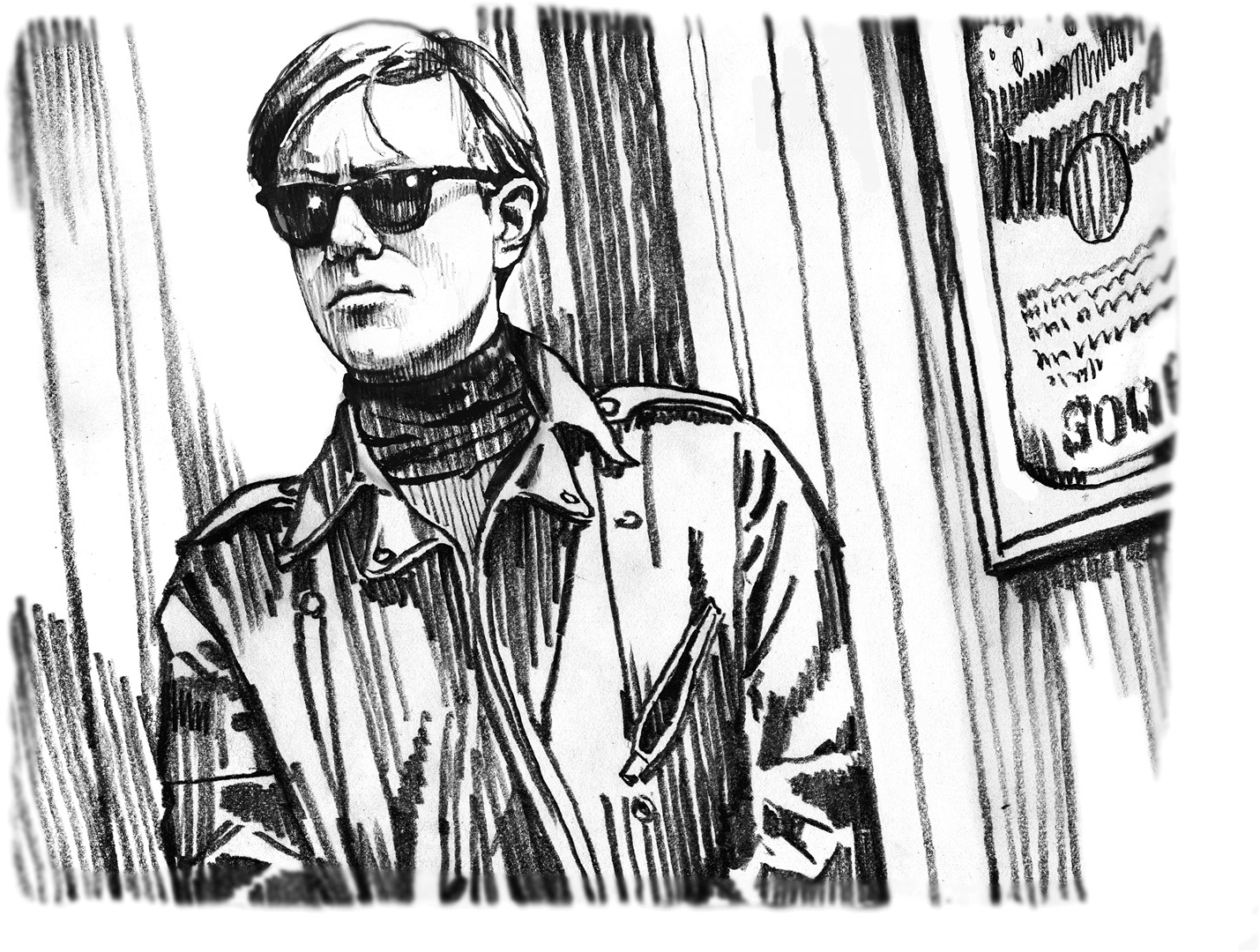

Andy used to wear button-down shirts and ties like all the other people who worked in advertising. Now he had a new look. It was more relaxed: black jeans, a black leather jacket, and boots. His wigs were more silver than white. He often wore sunglasses. Andy was still shy. But now when he was quiet, people thought he was being mysterious.

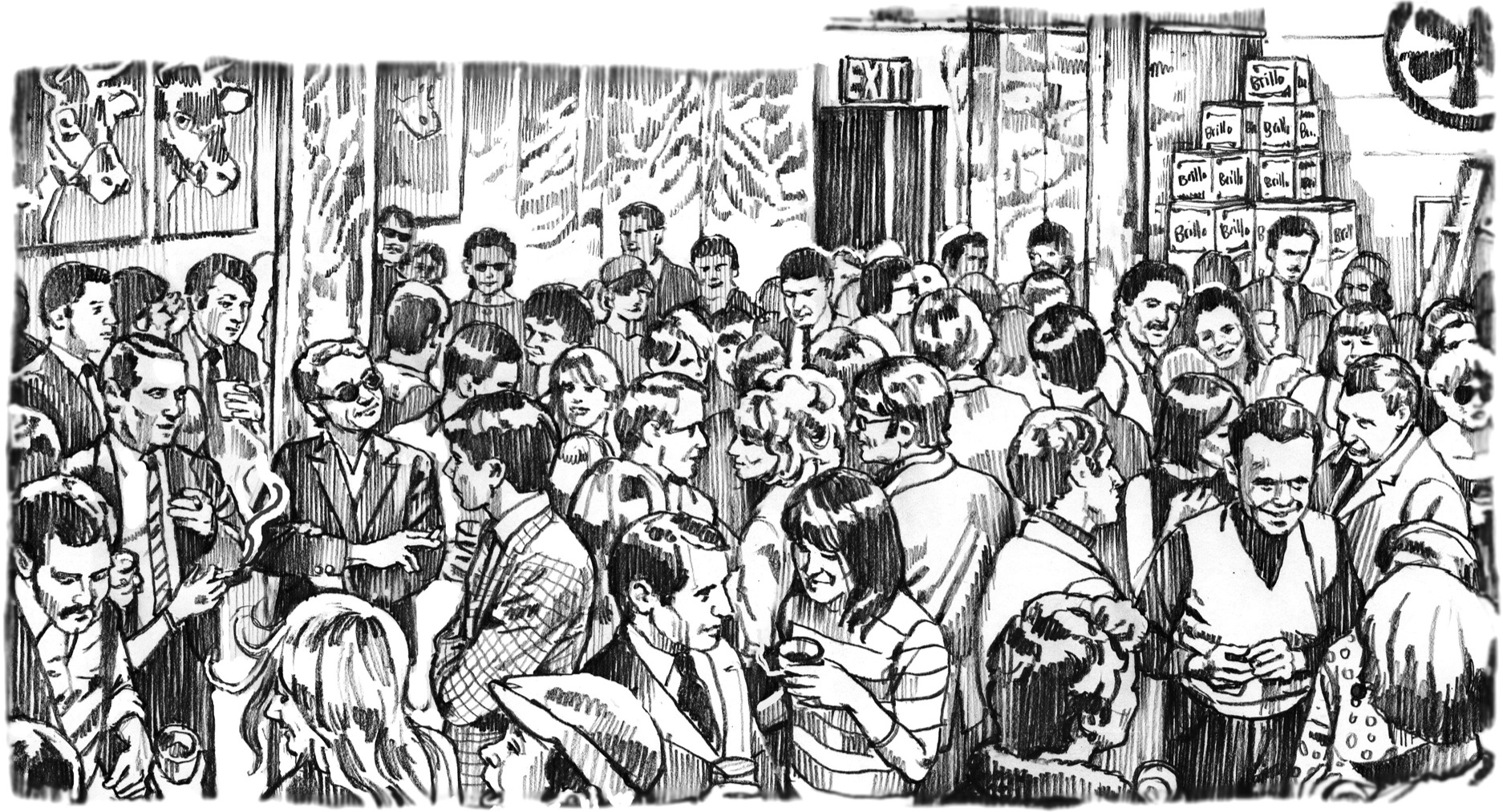

Andy and Gerard were working on Andy’s next show for the Stable. They silk-screened labels of products like Brillo pads onto giant boxes. They stacked them around the gallery. It looked like a grocery store. Many people came to see them, but few boxes were sold. Even big fans of Pop Art didn’t want to have piles of pot-scrubber boxes in their living rooms!

The party Andy threw after the show opened was a bigger success than the actual show. His uptown art buyer friends and his downtown artist friends all came together in the silver-covered studio. People who lived in fancy apartments on Park Avenue didn’t usually attend parties with shabby poets and dancers. But that was changing, especially at the Factory, which is what everyone now called Andy’s silver studio.

At first, people called it the Factory because it actually used to be a hat factory. Later, people said it was because Andy produced art like a factory. He was even quoted in a magazine, saying, “I’m becoming a factory.” But Andy never referred to his work space as the Factory. He always called it the “studio.”

Soon, all kinds of people began to show up at the Factory. An elevator opened right into the studio. Anyone could walk in. Some of Andy’s friends hung out there all day. Other people came to see Andy about art. Some just came because they thought it was a cool place to be seen.

Andy kept creating more artwork. He now showed at the Castelli Gallery—the same gallery that once turned him down because his work looked too much like Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings. Andy was now famous for his own style. Andy was not just any Pop artist. Many people thought he was the Pop artist.

In 1965, Andy and some friends flew to Paris, where an important gallery was showing some of his work. Andy made a big announcement there. He was retiring from painting. He was going to make movies.