Ehsan ul Haque and Khalid Hasan

In this chapter, we will look into developing new products, the lifeblood of an organization. The chapter will focus on the processes of developing new products. Though, their development is risky and many new products fail, once introduced, marketers want their products to enjoy long and happy lives. The case of a successful new product is presented as the basis for understanding new product development and launching.

A firm can obtain new products in two ways. One is through acquisition — by buying a company, a patent, or a license to produce someone else’s product. The other is through the firm’s own new-product development efforts. By new products we mean original products, product improvements, product modifications, and new brands that the firm develops through its own R&D efforts. This chapter focuses on new-product development.

New products are important to both customers and the marketers who serve them. They bring new solutions and variety to customers’ lives; they are also a key source of growth for companies. In today’s fast-changing environment, many companies rely on new products for their growth. For example, new products have almost completely transformed Apple in recent years. Sales of iPhone and iPad — neither of which was available just six years ago — now bring in 72 percent of the company’s total revenue.1

Yet, innovation can be very expensive and risky. New products face tough odds and many of them do not survive. By one estimate, 67 percent of all new products introduced by established companies fail. For new companies, the failure rate soars to 90 percent. Each year, U.S. companies lose an estimated $260 billion on new products that fail.2

Why do so many new products fail? There are several reasons. Although an idea may be good, the company may overestimate market size. The actual product may be poorly designed. Or it might be incorrectly positioned, launched at the wrong time, priced too high, or poorly advertised. A high-level executive might push a favorite idea despite poor marketing research findings. Sometimes the costs of product development are higher than expected, and sometimes competitors fight back harder than expected. So, companies face a problem. They must develop new products, but the odds weigh heavily against success. To create successful new products, a company must understand its consumers, markets, and competitors and develop products that deliver superior value to customers.

Rather than leaving new products to chance, a company must install strong new product planning and set up a systematic, customer-driven new-product development process for finding and delivering new products. Eight major steps in this process are the following:

New product development starts with idea generation — the systematic search for new product ideas. A company typically generates hundreds — even thousands — of ideas to find a few good ones. Major sources of new-product ideas include internal sources and external sources such as customers, competitors, distributors and suppliers, and others.

Internal idea sources: Using internal sources, the company can identify new ideas through formal R&D. However, in a recent study, only 33 percent of the surveyed companies rated traditional R&D as a leading source of innovation. In contrast, 41 percent of the companies identified customers as a key source, followed by heads of business units (35 percent), employees (33 percent), and the sales force (17 percent).3

Thus, beyond its internal R&D process, a company can pick the brains of its own people — from executives to salespeople to scientists, engineers, and manufacturing staff. Many companies have developed successful internal social networks and intrapreneurial programs that encourage employees to develop new-product ideas.

External idea sources: Companies can also obtain new-product ideas from any of a number of external sources. For example, distributors and suppliers can contribute ideas. Distributors are close to the market and can pass along information about consumer problems and new-product possibilities. Suppliers can tell the company about new concepts, techniques, and materials that can be used to develop new products. Competitors are another important source. Companies watch competitors’ ads to get clues about their new products. Companies also buy competing new products, take them apart to see how they work, analyze their sales, and decide whether they should bring out a (similar) new product of their own. Other idea sources include trade magazines, trade shows, web sites, seminars, government agencies, advertising agencies, marketing research firms, university and commercial laboratories, and inventors.

Perhaps the most important sources of new-product ideas are customers themselves. The company can analyze customer questions and complaints to find new products that better solve consumer problems, or it can invite customers to share suggestions and ideas.

Crowd sourcing: Many companies are now developing crowd sourcing or open-innovation new product idea programs. Crowd sourcing throws the innovation doors wide open, inviting broad communities of people — customers, employees, independent scientists and researchers, and even the public at large — into the new-product innovation process. Tapping into a breadth of sources — both inside and outside the company — can produce unexpected and powerful new ideas. Rather than creating and managing their own crowd sourcing platforms, companies can use third-party crowd sourcing networks, such as InnoCentive, TopCoder, Hypios, and Jovoto.

PayPal recently posted a challenge to the TopCoder community seeking the development of an innovative Android or iPhone app that would successfully and securely run its check-out process, awarding the winners $5000 each. After only four weeks of competition and two weeks of review, PayPal had its solutions. The Android app came from a programmer in the United States and the iPhone app from a programmer in Colombia.4 Crowd sourcing can produce a flood of innovative ideas. In fact, opening the floodgates to anyone and everyone can overwhelm the company with ideas — some good and some bad. For example, when Cisco Systems sponsored an open-innovation effort called I-Prize, soliciting ideas from external sources, it received more than 820 distinct ideas from more than 2,900 innovators from 156 countries. In the end, a team of six Cisco people worked full-time for three months to carve out 32 semifinalist ideas, as well as nine teams representing 14 countries in six continents for the final phase of the competition.5 Truly innovative companies do not rely only on one source or another for new-product ideas. Instead, they develop extensive innovation networks that capture ideas and inspiration from every possible source, from employees and customers to outside innovators and multiple points beyond.

The purpose of idea generation is to create a large number of ideas. The purpose of the succeeding stages is to reduce that number. The first idea-reducing stage is idea screening, which helps spot good ideas and drop poor ones quickly and efficiently. Product development costs rise greatly in later stages, so the company wants to develop only those product ideas that will turn into profitable products.

Many companies require their executives to write up new-product ideas in a standard format that can be reviewed by a new-product committee. The write-up describes the product or the service, the proposed customer value proposition, the target market, and the competition. It makes some rough estimates of market size, product price, development time and costs, manufacturing costs, and rate of return. The committee then evaluates the idea against a set of general criteria. One marketing expert proposes an R-W-W (“real, win, worth doing”) new-product screening framework that asks three questions. First, Is it real? Is there a real need and desire for the product and will customers buy it? Is there a clear product concept and will such a product satisfy the market? Second, Can we win? Does the product offer a sustainable competitive advantage? Does the company have the resources to make such a product a success? Finally, Is it worth doing? Does the product fit the company’s overall growth strategy? Does it offer sufficient profit potential? The company should be able to answer yes to all three R-W-W questions before developing the new-product idea further.6

An attractive idea must then be developed into a product concept. It is important to distinguish between a product idea, a product concept, and a product image. A product idea is an idea for a possible product that the company can see itself offering to the market. A product concept is a detailed version of the idea stated in meaningful consumer terms. A product image is the way consumers perceive an actual or potential product.

Suppose a car manufacturer has developed a practical battery-powered, all-electric car like Tesla. Its initial prototype is a sleek, sporty, roadster convertible that sells for more than $100,000; this is Tesla’s initial all-electric roadster.7 Later, more-affordable mass-market models will travel more than 300 miles on a single charge, recharge in 45 minutes from a normal 120-volt electrical outlet, and cost about one penny per mile to power. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer). However, in the near future it plans to introduce more-affordable, mass-market versions that will compete with recently introduced hybrid electric or all-electric cars such as the Chevy Volt and Nissan Leaf. This 100 percent electric car will accelerate from 0 to 60 miles per hour in 5.6 seconds. Looking ahead, the marketer’s task is to develop this new product into alternative product concepts, find out how attractive each concept is to customers, and choose the best one. It might create the following product concepts for this electric car:

• Concept 1: An affordably priced midsize car designed as a second family car to be used around town for running errands and visiting friends.

• Concept 2: A mid-priced sporty compact appealing to young singles and couples.

• Concept 3: A “green” car appealing to environmentally conscious people who want practical, no-polluting transportation.

• Concept 4: A high-end midsize utility vehicle appealing to those who love the space SUVs provide but lament the poor gas mileage.

Concept testing calls for testing new-product concepts with groups of target consumers to find out if the concepts have strong consumer appeal. The concepts may be presented to consumers symbolically or physically. Here, in more detail, is Concept 3: An efficient, fun-to-drive, battery-powered compact car that seats four. This 100 percent electric wonder provides practical and reliable transportation with no pollution. It goes 300 miles on a single charge and costs pennies per mile to operate. It is a sensible and responsible alternative to today’s pollution-producing gas-guzzlers. Its fully equipped price is $25,000.

Many firms routinely test new-product concepts with consumers before attempting to turn them into actual new products. For some concept tests, a word or picture description might be sufficient. However, a more concrete and physical presentation of the concept will increase the reliability of the concept test. After being exposed to the concept, consumers may be asked to react to it by answering questions, that is, through market research processes.

The research findings will help the company decide which concept has the strongest appeal. For example, the last question may be asked about the consumer’s intention to buy. Suppose two percent of consumers say they “definitely” would buy, and another five percent say “probably.” The company could project these figures to the full population in this target group to estimate sales volume. Even then, the estimate would be uncertain because people do not always carry out their stated intentions.

Marketing strategy development is designing an initial marketing strategy for a new product based on the product concept. Suppose the carmaker finds that Concept 3 for the electric car tests best. The next step is marketing strategy development, designing an initial marketing strategy for introducing this car to the market. The marketing strategy statement consists of three parts. The first part describes the target market, the planned value proposition, and the sales, market share, and profit goals for the first few years. The target market is thus younger, well-educated, moderate- to high-income individuals, couples, or small families seeking practical, environmentally responsible transportation. The car will be positioned as more fun to drive and less polluting than today’s internal combustion engine or hybrid cars. The company will aim to sell 50,000 cars in the first year, at a loss of not more than $15 million. In the second year, the company will aim for sales of 90,000 cars and a profit of $25 million.

The second part of the marketing strategy statement outlines the product’s planned price, distribution, and marketing budget for the first year. The battery-powered all-electric car will be offered in three colors — red, white, and blue — and will have a full set of accessories as standard features. It will sell at a retail price of $25,000, with 15 percent off the list price to dealers. Dealers who sell more than 10 cars per month will get an additional discount of 5 percent on each car sold that month. A marketing budget of $50 million will be split 50 and 50 between a national media campaign and local event marketing. Advertising, the Web site, and various digital content will emphasize the car’s fun spirit and low emissions.

During the first year, $100,000 will be spent on marketing research to find out who is buying the car and what their satisfaction levels are. The third part of the marketing strategy statement describes the planned long-run sales, profit goals, and marketing mix strategy. We intend to capture a three percent long-run share of the total auto market and realize an after-tax return on investment of 15 percent. To achieve this, product quality will start high and be improved over time. Price will be raised in the second and third years if the competition and the economy permit. The total marketing budget will be raised each year by about 10 percent. Marketing research will be reduced to $60,000 per year after the first year.

Business analysis is a review of the sales, costs, and profit projections for a new product to find out whether these factors satisfy the company’s objectives.

Once management has decided on its product concept and marketing strategy, it can evaluate the business attractiveness of the proposal. Business analysis involves a review of the sales, costs, and profit projections for a new product to find out whether they satisfy the company’s objectives. If they do, the product can move to the product development stage. To estimate sales, the company might look at the sales history of similar products and conduct market surveys. It can then estimate minimum and maximum sales to assess the range of risk. After preparing the sales forecast, management can estimate the expected costs and profits for the product, including marketing, R&D, operations, accounting, and finance costs. The company then uses the sales and costs figures to analyze the new product’s financial attractiveness.

It refers to developing the product concept into a physical product to ensure that the product idea can be turned into a workable market offering. For many new-product concepts, a product may exist only as a word description, a drawing, or perhaps a crude mock-up. If the product concept passes the business test, it moves into product development. Here, R&D or engineering develops the product concept into a physical product. The product development step, however, now calls for a huge jump in investment. It will show whether the product idea can be turned into a workable product. The R&D department will develop and test one or more physical versions of the product concept. R&D hopes to design a prototype that will satisfy and excite consumers and that can be produced quickly and at budgeted costs. Developing a successful prototype can take days, weeks, months, or even years depending on the product and prototype methods. Often, products undergo rigorous tests to make sure that they perform safely and effectively, or that consumers will find value in them. Companies can do their own product testing or outsource testing to other firms that specialize in testing. Marketers often involve actual customers in product testing.

Test marketing is the stage of new-product development in which the product and its proposed marketing program are tested in realistic market settings.

If the product passes both the concept test and the product test, the next step is test marketing, the stage at which the product and its proposed marketing program are introduced into realistic market settings. Test marketing gives the marketer experience with marketing a product before going to the great expense of full introduction. It lets the company test the product and its entire marketing program — targeting and positioning strategy, advertising, distribution, pricing, branding and packaging, and budget levels. The amount of test marketing needed varies with each new product. Test marketing costs can be high, and it takes time that may allow competitors to gain advantages. When the costs of developing and introducing the product are low, or when management is already confident about the new product, the company may do little or no test marketing. In fact, test marketing by consumer-goods firms has been declining in recent years. Companies often do not test-market simple line extensions or copies of competitors’ successful products. However, when introducing a new product requires a big investment, when the risks are high, or when management is not sure of the product or its marketing program, a company may do a lot of test marketing.

As an alternative to extensive and costly standard test markets companies can use controlled test markets or simulated test markets. In controlled test markets new products and tactics are tested among controlled panels of shoppers and stores. Using simulated test markets, researchers measure consumer responses to new products and marketing tactics in laboratory stores or simulated online shopping environments. Both controlled test markets and simulated test markets reduce the costs of test marketing and speed up the process.

Introducing a new product into the market is termed as commercialization. Test marketing gives management the information needed to make a final decision about whether to launch the new product. If the company goes ahead with commercialization — introducing the new product into the market — it will face high costs. For example, the company may need to build or rent a manufacturing facility. And, in the case of a major new consumer product, it may spend hundreds of millions of dollars for advertising, sales promotion, and other marketing efforts in the first year.

A company launching a new product must first decide on introduction timing. If the new product will make demands on the sales of other company products, the introduction may be delayed. If the product can be improved further, or if the economy is down, the company may wait until the following year to launch it. However, if competitors are ready to introduce their own competing products, the company may push to introduce its new product sooner. Next, the company must decide where to launch the new product — in a single location, a region, the national market, or the international market. Some companies may quickly introduce new models into the full national market. Companies with international distribution systems may introduce new products through swift global rollouts. General Motors did this with its global car, the new Malibu, which will be sold in 100 countries on six continents. The global Malibu launch was backed by live, high-definition video run on Facebook and various mobile media, timed to coincide with major auto shows in both Shanghai and New York. The car’s designers and marketers were available in a live Web session to field consumer questions posted on Twitter or Chevrolet’s Facebook page.8

Acknowledgment: The chapter is adapted from Principles of Marketing — A South Asian Perspective 13th Edition, Prentice Hall India, written by Professor Ehsan ul Haque, co-authored with Professor Philip Kotler, Professor Gary Armstrong, and Professor Prafulla Y Agnihotri. Received written permission from Pearson. Copyright © Dorling Kindersley (India) Pvt. Ltd.

CASE: NEW PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

Procter and Gamble, Pakistan: The Ariel Launch

Ehsan ul Haque

This case is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Some non-public data have been disguised and some business details have been simplified to aid in classroom discussion.

Tahir Malik, Assistant Brand Manager for Ariel, a laundry detergent brand of Procter and Gamble, Pakistan (P&G), faced some critical decisions as he finalized the marketing plan for Ariel’s launch. The launch would be a culmination of almost two years of extensive research and development efforts that Tahir and other team members had put in. In addition, Ariel would be the company’s first entry into Pakistan in a product category that was extremely important for P&G worldwide. Both P&G headquarters in Cincinnati and regional head office in Brussels were keenly following this launch. It was the middle of May, 1997 and Ariel was scheduled for launch in less than two months.

There were many elements of the introductory plan where the launch team had differences of opinion. The first concern was about the appropriate positioning of the brand. High-quality detergents in Pakistan were typically targeted at the more affluent classes and priced accordingly. According to Tahir, Ariel was technically far superior to any other brand in Pakistan and, consequently, it also costs more. Market research had shown that consumers were willing to pay for quality. However, Tahir worried whether premium positioning will cost him the mid-market which was critical for long-term sustainability of the brand. Decisions on packaging, price, and advertising copy would depend on the overall positioning decision. In addition, Tahir was debating whether to go for a fairly aggressive sampling program which could end up delaying the launch, apart from raising a few implementation issues. On top of everything, he needed to respond to recently arrived Vice President, Philippe Bovay’s question as to why was Ariel trying to introduce a fluffy formulation of the product while some South Asian countries were experimenting with a technologically more advanced compact formulation.

In 1837, two businesspersons founded Procter and Gamble in Cincinnati, Ohio. Starting from a humble soaps and candles business, P&G grew steadily to become a leading consumer products company in the world over the next 160 years. In 1996, sales from 140 countries had crossed the $30 billion mark. Key product groups and brands were as follows:

• Baby Care (Pampers, Luvs, Bibsters)

• Feminine Care (Always, Alldays, Tampax)

• Beauty Care (Max Factor, Oil of Olay, Pantene, Sure, Head & Shoulders)

• Fabric and Home Care (Tide, Downy, Dawn, Bounce)

• Food and Beverages (Pringles, Folgers, Sunny Delight)

• Health Care (Vicks, Thermacare, Crest, Scope)

• Tissues and Towels (Bounty, Charmin, Puffs)

P&G’s philosophy, as stated in its brochures, was:

We will provide products of superior quality and value that best fills the needs of the world’s consumers. We will achieve that purpose through an organization and a working environment which attracts the finest people; fully develops and challenges our individual talents; encourages our free and spirited collaboration to drive the business ahead and maintains the company’s historic principles of integrity and doing the right thing. Through the successful pursuit of our commitment, we expect our brands to achieve leadership share and profit positions and that, as a result, our business, our people, our shareholders and the communities in which we live and work, will prosper.

P&G entered the Pakistani market by signing a joint venture agreement with a local partner in 1989. Initially, it only distributed a few products such as Oil of Olay, Vicks, etc. However, by 1993, local manufacturing capacity was added through a plant in Hub, Baluchistan, to manufacture Camay beauty soap. By 1995, the company had expanded its portfolio in Pakistan to include shampoos such as Pantene, Pert Plus, and Head & Shoulders. The annual growth rates were impressive at 25–30 percent over the last few years. According to the Chairman of the Board, J. E. Pepper:

P&G’s goal is to be the finest consumer goods company in Pakistan…. Pakistan offers one of the greatest opportunities for growth that P&G has in the world. Ten years from now we should be many times larger than we are today, and I am confident that we will be. And even then we’ll have enormous opportunities. We are in Pakistan to build a great business over time.

With this goal in mind, the company was set to introduce a number of brands over the next few years. Detergent was a core category of P&G globally. Management believed that it could provide the scale that P&G needed in Pakistan. Hence, they assigned Tahir the task of finding out the viability of launching a detergent brand. Tahir had joined the company in June 1995 after his MBA from Institute of Business Administration — IBA, Karachi.

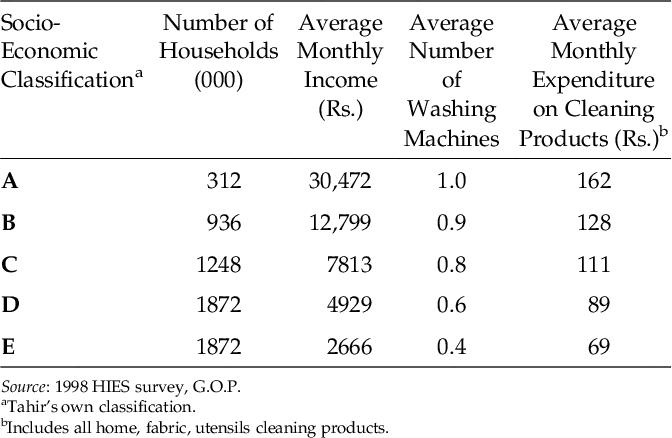

With a population of about 131 million in 1997, 42 million living in the urban areas, Pakistan was a large market for most consumer goods. Extrapolations from selected government household statistics are presented in Exhibit 1. In order to understand the detergent consumption behavior of urban Pakistanis, Tahir carried out innumerable qualitative studies in addition to conducting a large-scale quantitative study.

For almost two years we visited all kinds of Pakistani households in Karachi, Lahore, Gujranwala, Faisalabad, etc., observed homemakers doing their laundry, talked to them to find out what were their opinions and feelings about the task itself and various products/brands used.

It was clear from these in-depth interviews that Pakistani homemakers took their laundry very seriously. A large majority used the relatively inexpensive bar soaps, typically priced from Rs. 5–10 for a 250-gram bar, for regular laundry while more expensive detergents, commonly called washing powders, were primarily used for delicate clothes or woolies. Even the higher income households would use bar soaps regularly. It seemed to Tahir that Pakistani homemakers were more performance oriented rather than just price oriented. The eating habits of Pakistanis presented special cleaning challenges. For example, stains from tea, beetle juice, spicy gravies and various ketchups and chutneys were tough to clean. Homemakers would use supplements such as lemon, bleach, and scrubbing by hard brushes to take some of these stains out. They would also use some bluing agent (Neel) to give a shining white appearance to white clothes. Soap users were very demanding. They considered the “sudsing” capacity of soap as its indicator of cleaning power and generally considered soap as the gold standard for cleaning. On the other hand, detergent users did not seem fully satisfied with the cleaning power of their detergents. Tahir was surprised to find that many homemakers took a lot of pride in providing clean clothes for their families. Clean clothes seemed to reassure females that they were good mothers and homemakers.

A homemaker would typically allot two days in a week for laundry. As the washing machine penetration was fairly high (almost 85 percent in the middle- and upper-class urban households) most homemakers would use machines in addition to some hand washing for highly soiled clothes. On the laundry day, the accumulated load (around 30–40 items) would be separated into three piles. The homemaker would typically use one bar soap, cut into small pieces to dissolve and make suds easily, in the machine and put the first pile in. After the completion of washing cycle the clothes would be taken out for hand rinsing and the second pile would be washed using the same suds and the cycle would repeat for the last pile. The homemaker felt that the cleaning power of soaps was good enough for three washes; however, detergents were only good for one wash. As opposed to very common use of washing machines, use of dryers was fairly rare in Pakistan and most clothes were hung out to dry in the sunshine.

For a quantitative survey, a study of 1300 homemakers in three large Pakistani metropolitan areas was undertaken in late 1996. Key findings from the survey are reported in Exhibit 2.

According to Tahir:

Our extensive research had led us to the firm belief that the products in the market were good but consumers were not interested in merely good products- they wanted to take on the status quo, something that truly excelled. We know that Pakistani consumers were high-end achievers and they deserved nothing but the best. This seems to be a classical setup for a typical P&G launch: come in with the best product and establish a relationship with the consumer based on superior product performance and value.

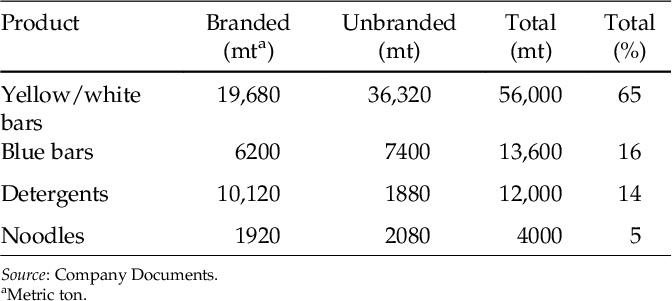

The laundry market was served by a variety of products such as bar soaps, detergents, noodles, etc. In 1988, the total urban tonnage was about 68,000 metric tons of which the share of detergent was approximately 10 percent. The market was growing; however, an audit of 3000 urban retail outlets conducted in 1996 suggested that the dominance of bar soaps was still intact. Over the last eight years the urban laundry market in Pakistan had grown to an estimated 85,600 metric tons. The share of detergent powders had grown to 14 percent while different variations of bar soaps still comprised the rest (see Exhibit 3).

Bar soaps typically came in two types: yellow/white and blue. The yellow/white soaps were made from tallow (extracted from natural animal fat) and contained some caustic soda. The cleaning power of such soaps was very good; however, they were somewhat harmful for the skin. These bars could easily be cut into small pieces to be used in the washing machine and made lots of suds. The blue bars were made of synthetic chemicals, were somewhat difficult to cut into small pieces and made relatively less suds. Blue bars for fabric wash were introduced by Lever Brothers in the shape of Rin in 1984. While Rin was positioned as a fabric wash product, consumers kept on using it for dish wash. Lever, eventually, dropped Rin from the Pakistani market after its efforts to reposition the brand did not succeed. The bar market was highly fragmented with dozens of branded and unbranded products; however, the number of nationally available and advertised bars was not more than 10. Sufi soap had the leading share in the bar market (see Exhibit 4).

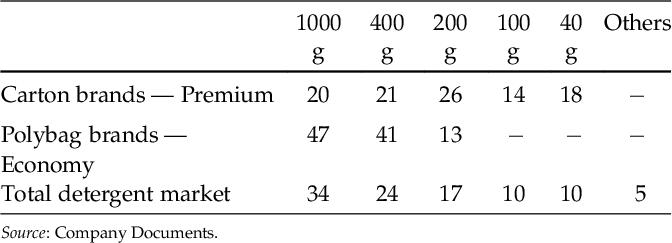

Detergents came in various sizes and packaging materials. All premium brands were sold in carton packaging and most sales came from the smaller SKUs. This was understandable as the market was price sensitive and detergents were used for special purposes, especially by the large middle class of consumers. On the other hand, almost all economy brands and unbranded detergents came in plastic pouch (polybag). Given the large size of a typical Pakistani household (a little more than six persons per household) the larger SKUs of polybags were more popular (see Exhibit 5).

Lever Brothers and Colgate Palmolive were two major players in the detergent category. Lever Brothers was a subsidiary of the multinational, Unilever, and had a presence in Pakistan prior to the creation of the country in 1947. Lever’s brands in most product categories, such as, beauty soaps (Lux), detergents (Surf), shampoos (Sunsilk), toothpastes (Close-up), vegetable oils (Dalda), tea (Lipton), etc., were well entrenched in urban Pakistan and seen as highest quality products in their categories. In the year ending June, 1997, Lever Brothers made a pretax profit of Rs. 831 million on sales of Rs. 15.24 billion.

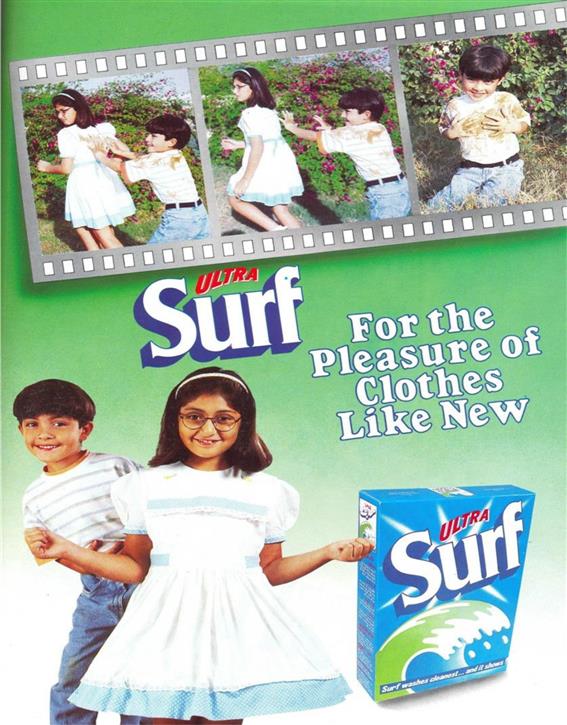

Lever had two detergent brands: Surf for the premium segment and Sunlight for the economy segment. Surf was a very well-known brand so much so that many Pakistanis used the brand name Surf as the generic name for detergents. For competitive market shares, distribution coverage and typical prices see Exhibit 6. A typical Surf ad is shown in Exhibit 7.

Colgate Palmolive Pakistan Limited was a Pakistani company with collaborative arrangements with the multinational Colgate Palmolive. Colgate also carried a broad assortment of personal, fabric and home care products. In 1997, Colgate earned a pretax profit of Rs. 58 million on sales of Rs. 1.02 billion. Colgate brands in the detergent category were Brite for the premium market and Express for the economy market. In 1996, Colgate had introduced Bonus at even lower prices and had met with a good response in a short time.

Tahir felt that the competition had not done enough to develop the detergent market. According to him:

A detergent consists of three key ingredients; Surfactants to create suds and clean dirt, Builders to cut grime and to provide better whiteness, and Enzymes to clean most obstinate stains. Different enzymes are needed for different staining agents. When we started our investigations, we found out that none of the competitive brands contained any enzyme. I suppose the reason was the high cost of adding enzymes which would make the detergent even more expensive. However, it also explained why the consumers were unhappy with detergents.

In addition, the growth rate of detergents was fairly static. There was little effort to convert soap users to detergents. We had international experience which suggested that this process could be accelerated with the right marketing strategy. In the early 80s, Egyptian consumers were very much like Pakistani consumers, primarily using bar soaps for laundry. However, P&G had successfully converted a little more than 50% of this market to detergents with its very successful launch of Ariel brand. The brand was priced at parity with soap and the conversion had taken place within six years. I went to Egypt to study their experience.

Armed with voluminous consumer and competitive data, Tahir set about finding a P&G detergent brand that would meet the needs of the Pakistani consumers. After some research it was decided that while the Ariel brand would be most appropriate, its formulation would need to be customized to meet the special Pakistani cleaning requirements.

We sent tons of loads of specially soiled clothes, as well as shipped six Pakistani washing machines, to our R&D facility in Brussels in order to come up with an appropriate Ariel formulation. Suds were important, fabric enhancers were important as our clothes dry in the sun, multi-load capability was important as consumers were used to three loads per soap. Various surfactants, builders and enzymes were experimented with to finally come up with a formulation which was a high quality offer for the Pakistani market. However, its high cost was a big challenge.

Tahir and his team checked the efficacy of the new formulations with many homemakers. They provided a day’s worth of sample to homemakers for their regular laundry. Most homemakers were pleasantly surprised to see the cleaning power of the product.

In order to address the high cost issue, P&G management explored two approaches. First, they could use polybag packaging as opposed to cartons. This could reduce the cost of packaging by 10 to 20 percent. Second, they could play around with the size of the smaller SKUs. Competitive SKUs were available in 40 and 100 grams. P&G research had suggested that 80 grams of Ariel were good enough for a day’s wash (three loads). It was believed that these two approaches combined could allow P&G to competitively price the product despite its higher cost.

The next item on Tahir’s mind was the communication strategy. Most premium brands were targeted toward SEC A and B householdsa and were, according to Tahir, making tall claims of cleaning clothes using primarily image advertising. Glamorous models were shown using the product in rich households. The economy detergents and the few soap brands that did advertise were focusing on low price.

The Ariel team believed that detergents needed to be sold on performance rather than image. Their extensive research on communication strategy with the homemakers led them to select “superior cleaning and tough stain removing ability” as Ariel’s key strategic benefit. The question was why would skeptical homemakers believe this claim? Once again, consumer research assisted the team in selecting “because only Ariel has all the required additives (bluing agent, stain digesters, enzymes, etc.) already built in the product” as the “reason to believe” (RTB) in Ariel messages. The team felt that in order to attract soap users to convert to detergent a “brand of the people” format should be used. Consequently, it was decided that a “real life testimonial” (RLT) approach to advertising appeal will be used. The advertising agency alerted the Ariel team that this approach could associate the product too closely with the middle class. However, Tahir and his team, armed with a camera man, spent three months in various public places seeking permissions from husbands and requesting homemakers from Pakistani middle class to participate in a laundry cleaning challenge using Ariel and an anonymous competitive brand. The results were great and the post-cleaning “wow” expression on the face of the homemakers and their consequent praise of the Ariel brand were captured for use in proposed TV ads (see Exhibit 8).

The Ariel team considered some innovative ways for retail presentation of the brand as well. Detergent brands were typically put on shelves with other laundry products in relatively remote parts of the stores. The team felt that in order to involve the customer, Ariel should be brought toward the more visible, front part of the store. However, that needed special display equipment, as polybags would not stand on their own as cartons would. Special hangers were designed to work as stand-alone display-cum shelf for Ariel. The challenge was to convince the retailers to accept this placement, which disrupted their normal category placement habits. Tahir wondered whether he would need to increase the regular 8 percent margin provided by competition to retailers for detergents.

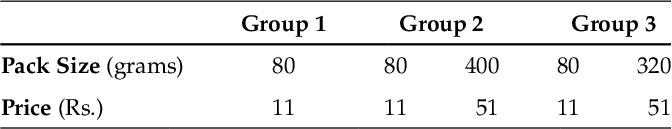

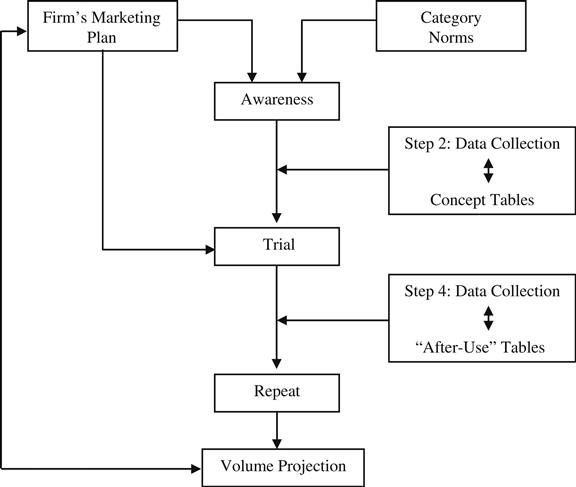

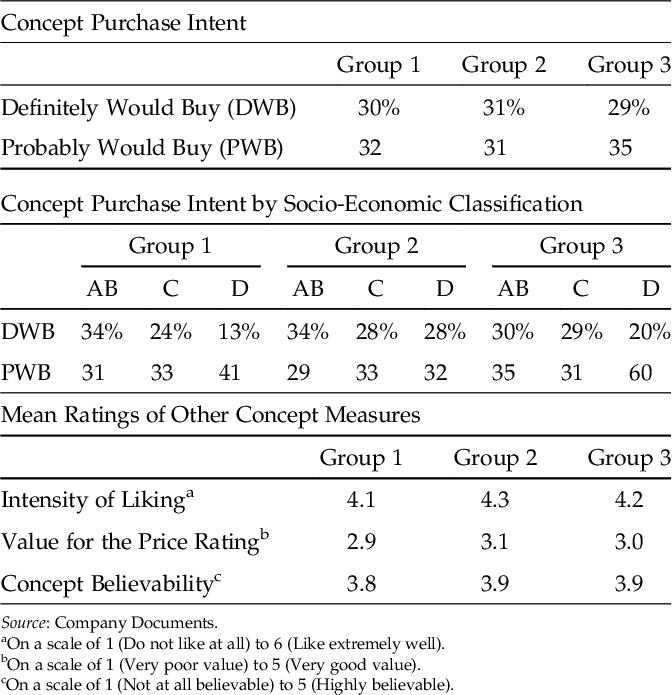

Management had decided that BASES (see Exhibit 9) would be used to determine the volume projections for Ariel under various marketing investment scenarios. The research was conducted in the three major cities of Pakistan (Rawalpindi/Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore). Interviews were conducted with 945 females who were 18 years or older and were the principal shoppers or brand deciders for household products. The sample was divided into three groups which were exposed to slightly different product and price combinations as shown below:

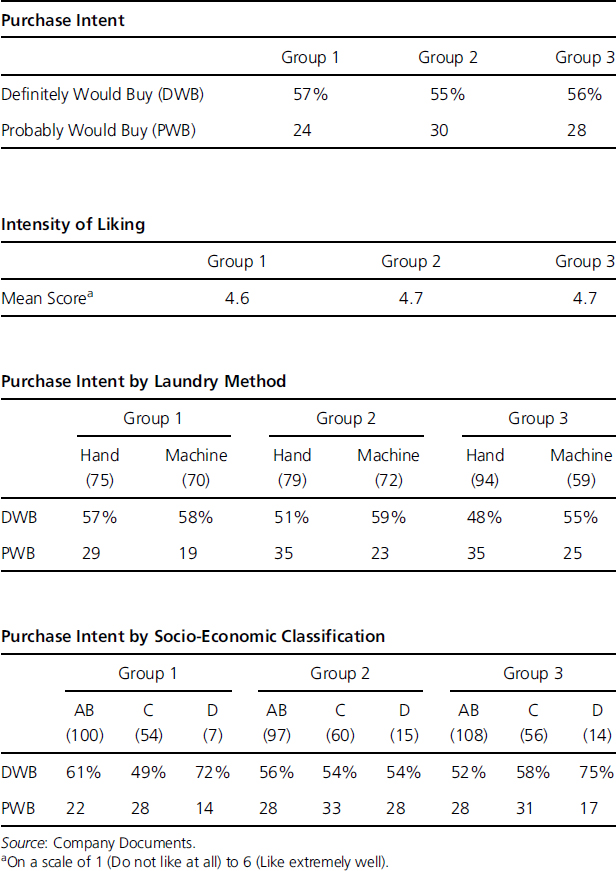

In the first round of interviews, after preliminary questions about their laundry habits, respondents were exposed to the relevant Ariel concept board (see Exhibit 10) to assess their purchase intentions and likings or otherwise of the concept. Homemakers, who had shown higher purchase interest (top two boxes), were provided with a sample of the product for home use. The second round of interviews took place after two weeks.

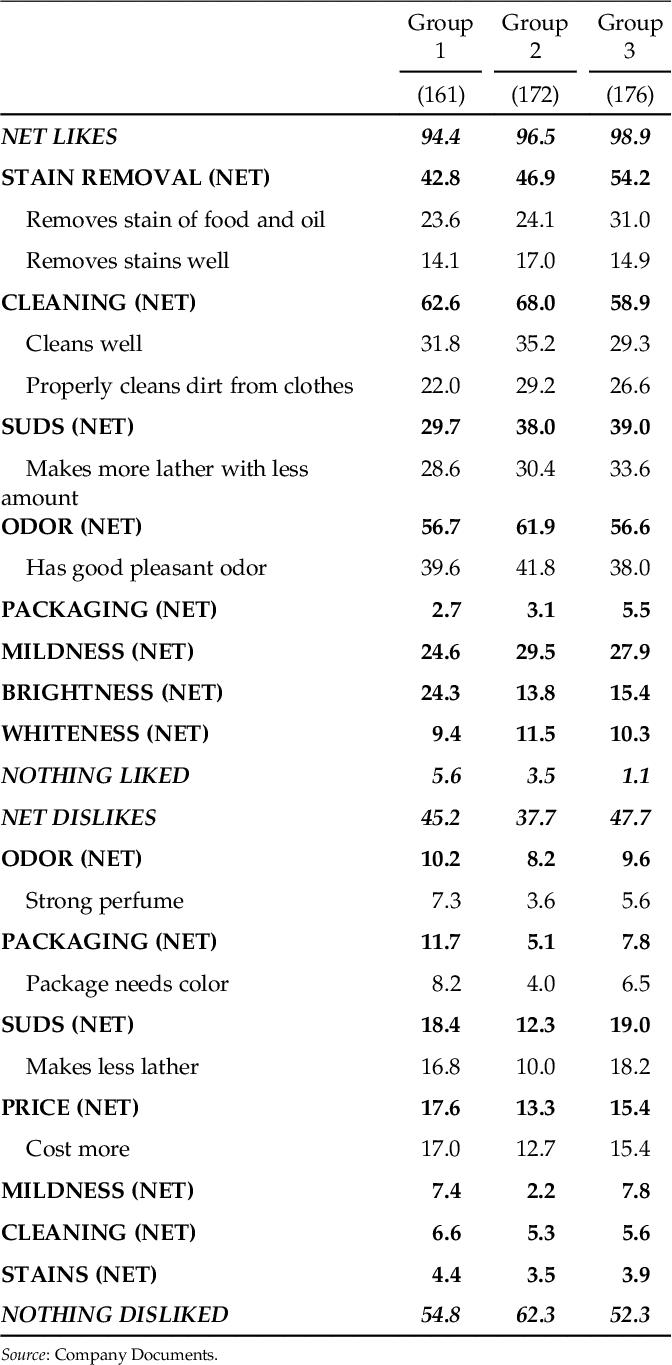

Exhibits 11–14 present selected results of this survey. Data from this survey and marketing strategy inputs from Ariel team were then used by BASES researchers in the United States to project volume, market share, and profit estimates for the launch.

Ariel was generally liked by the homemakers. The projections showed that initial sales would be strong; however, there were still many areas of concerns for the Ariel team.

Tahir’s immediate boss and brand manager, Ijaz Basrai, was unhappy at the bottom line numbers. He felt that positioning a high cost and technologically sophisticated product at the mass market was a gamble. The volumes would only come if a significant number of soap users would convert to detergent. Lever Brothers had not been able to do it despite many decades of presence in the market.

Let us not forget that bar soaps are pretty good and pretty cheap.

Also, what is the current image of Ariel in Pakistan? Smuggled Ariel cartons are already available in the high-end retail outlets in Pakistan. They are all priced way above local Surf. Most upscale Pakistani homemakers also have been exposed to international Ariel ads on satellite channels. The current image of Ariel for this small market is anything but super premium. Why should we not leverage it?

In any case, we seem to be giving very confusing mixed signals. Our proposed polybag packaging and RLT ads give a clear mass-market image, which will turn off the high income households, our primary detergent buyer. Look at our concept test scores. They are in the bottom third of our norms. I understand that we do not have Pakistani norms to compare them with but still they are not great? Our proposed price, on the other hand, is even higher than the premium segment! And that we have barely managed after exhausting all our cost variables. Why not simply position Ariel in the premium segment, change the packaging, the ads and increase the price to boot. I understand that volumes will be lower but we can make it up in gross margins. At least our breakeven will be easier to achieve as we will not be spending a lot of money trying to create category need amongst soap users. Even the BASES data seem to suggest that homemakers are not averse to paying a higher price!

Tahir, on the other hand, felt that scale would only be possible with a mass-market positioning. Unfortunately, the high costs of the product meant that mass pricing was out of question. For pricing the various SKUs, there was debate whether to price them close to a typical soap, close to Surf or higher because of Ariel’s superior cleaning ability and high costs. Tahir knew that changing long-held beliefs of consumers was not easy. If homemakers continued to use detergents for special purpose washing only, then the scale that he was so dependent upon for clearing the profitability threshold would not be attained.

The team was, however, very excited at the after-use purchase intent scores of the BASES survey. They were all in the top third of norms. The homemakers who used the product had really liked it. Tahir felt that this product superiority called for an aggressive trial generation plan. He believed that no matter how good their ad campaign was, it would take a few years to create mass awareness and conviction in homemakers. The team thought that in conjunction with the Ariel launch, they could ask a marketing services company to carry out a large scale sampling program to reach approximately two million households and encourage homemakers to actually try the sample. As this scale of free sampling could impact retail sales, making the channel unhappy, the team thought that instead of free sampling the homemakers could be asked to purchase the 80 grams package at the expected retail price. However, as an incentive they could be provided with one free package with each purchase.

The first problem that Tahir faced with this sampling proposal was that it was simply too expensive. It hurt the forecasted bottom line even further and had the potential to delay the expected breakeven time by a year. To make matters worse Tahir found out that such a massive door-to-door sampling program had never been carried out in Pakistan. Hence, no marketing services supplier had the infrastructure to carry it out. One organization suggested that they could establish a special company for this purpose. However, getting the people on board and training them would mean a delay of at least two months to launch Ariel. Many other implementation issues, especially those of pilferage, were expected but nobody had the experience even to predict their impact. Tahir wondered whether he was going for overkill. He might just increase the media weights for the launch.

Philippe Bovay had a different concern with Ariel plans altogether. He had moved to Pakistan only in the early 1997. He felt that the developed world was moving away from fluffy formulation of detergents to compact formulations. Europe had already stopped the production of fluffy formulation. Compact formulations were more concentrated and a 250-gram package could provide two weeks of cleaning as opposed to one week’s worth of cleaning provided by 400-gram fluffy formulation. In South Asia, Bangladesh and India were experimenting with the compact version. The Indian experience was not very positive; however, in Bangladesh, the slogan of “Teen Taka Toni Tek” (superior cleaning for Rs. 3 only) was pretty popular. Philippe asked why the same cannot be done in Pakistan. Tahir felt that the Pakistani homemakers were volume conscious and might not buy the argument that such a small packet can clean so many clothes. He conducted a “quick and dirty” survey of 200 homemakers to test their acceptance of the compact concept. Hundred homemakers each were given either a compact sample or a fluffy sample. Interviews after one week of use suggested that homemakers were happier with fluffy formulations. They even thought it cleaned better. Tahir wondered whether Philippe would be convinced with his convenience sampling.

While Tahir researched the viability of the Ariel launch, the news had spread like wildfire amongst competitors. Both Colgate and Lever quickly launched technically more sophisticated versions of their brands and increased the media weights considerably. There was a buzz of expectancy in the market. P&G top management felt that they had spent enough time and resources over the detergent project. They asked Tahir to present his final marketing strategy in a couple of days. As Tahir grappled with fine tuning his proposed launch date and strategy, he could not help but squirm when his sales team informed him that both Lever and Colgate are slated to launch yet another improved version of their brands, specifically focusing on the cleaning power of their brands. Competitive launch dates were rumored to be within two months.

As the clock struck 10 p.m., Tahir realized that another day was over and time was running out fast.

1. What decision(s) need to be made by Tahir, and what factors would you keep in mind in reaching these decisions?

2. What is the detergent consumption behavior like in Pakistan? How does it impact Tahir’s plans?

3. What are some of the key findings of competitive analysis?

4. What seems to be Procter and Gamble’s approach to new product development? How do you evaluate it?

5. As Tahir what decision(s) would you take with respect to the timing of the launch of Ariel, its positioning and other elements of its marketing mix? Why?

Exhibit 1: Selected Urban Household Data.

Exhibit 2: Selected Data from Quantitative Survey.

Products Used Most Often for Laundry |

||

Bar soap |

55% |

|

Bar soap only |

|

39% |

Bar soap mostly |

|

16 |

Washing powder |

38 |

|

Washing powder only |

|

25% |

Washing powder mostly |

|

13 |

Equally |

4 |

|

Soap noodles only |

3 |

|

Methods Used for Laundry |

||

Hand wash |

26% |

|

By hand only |

|

20% |

By hand mostly |

|

6 |

Machine wash |

70 |

|

By machine only |

|

37% |

By machine mostly |

|

33 |

Equally |

4 |

|

Average Frequency of Purchase |

||

Product |

|

Number of Times/Year |

Powder |

|

17 |

Bars |

|

24 |

Noodles |

|

12 |

Types of Outlets Typically Used for Shoppinga |

||

Outlets |

|

% Respondents |

Kiryana stores |

|

45 |

General stores |

|

32 |

Utility stores |

|

22 |

Super markets |

|

10 |

Wholesale |

|

5 |

Friday bazaar |

|

2 |

Other |

|

3 |

Source: Company Documents.

aMore than one answer permitted.

Exhibit 3: Urban Laundry Market Size 1995–1996.

Exhibit 4: Urban Laundry Sales and Market Shares.

Company |

Volume Share (%) |

Value Share (%) |

Lever brothers |

6.4 |

17.8 |

Colgate-Palmolive |

5.4 |

11.6 |

Sufi soap |

6.4 |

5.5 |

Gae soap |

4.6 |

3.0 |

101 soap |

3.2 |

2.4 |

Lado soap |

2.9 |

1.5 |

Time soap |

2.5 |

1.9 |

Millan soap |

1.8 |

1.2 |

Reshma soap |

1.4 |

0.9 |

All others |

65.4 |

54.2 |

Source: Company Documents.

Exhibit 5: Volume Shares by SKUs (Percentages).

Exhibit 6: Data of Selected Detergent Brands.

Exhibit 7: Surf Print Ad. Source: Company Documents.

Exhibit 8: Storyboard of a Proposed Ariel Ad.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Presenter: Is it true that Europe’s leading washing powder, Ariel, really cleans the clothes? |

Presenter: Are you satisfied with your laundry soap? |

Presenter: Compared to your soap, Ariel can really clean your clothes |

We are here in Karachi to test this with some ladies. |

Female: No! Soap does not remove stains, especially from children clothes |

Female: I have used so many different soaps. When I am not satisfied with them then how do you expect me to believe that a powder can give me such cleaning in one wash. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Presenter: Let’s get some men’s coveralls dirty in a competitionFemale: Oh no! he has really messed up his clothes |

Presenter: Now, let’s take your soap and put it in this machine. |

Presenter: We will put new Ariel in the other machine. Only Ariel contains stain digesters, bluing agent and the power of soap which render your clothes not just clean but really clean |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Presenter: This is the coverall cleaned with your soap |

Presenter: Now let’s look at the coverall cleaned by Ariel |

Presenter: So we have proven that the new Ariel does not merely clean clothes but it really cleans them |

Female: I told you that we will not get the right cleaning. You can see that the soap could not remove mud stains. |

Female (Visibly impressed): Well! It is pretty obvious. This coverall is really clean and shiny. |

Female: I would definitely call it excellent. |

Source: Company Documents.

Exhibit 9: BASES Model.

Historically, the new product development process has been characterized by four stages, i.e., Idea generation; Concept testing; Product use test; and Test Market. These stages were expected to weed out poor products in the early stages. Marketers, however, felt that too many “defectives” were getting through to the expensive test-market stage. Consequently, beginning in the early 1970s, there were a number of efforts (generally labeled as Pre-Test Market Models) made to provide a useful intermediate step between the in-home product use test and a full test market. BASES is one of these models developed by SAMI/Burke.

The objective of BASES is to provide sales volume estimates for years 1 and year 2 following a product launch. For this purpose a special survey of target market is carried out and data for variables, such as, trial rate, repeat purchase rate, purchase volume and other diagnostics, are collected. Researchers then use this data coupled with marketing plan data supplied by the product launching firm and industry norms data from BASES’ extensive database of previous tests to predict sales volumes.

A conceptual structure of BASES is shown below:

Source: Excerpted from Prof. Robert J Dolan’s “Note on Pretest Market Models”. HBS (1988).

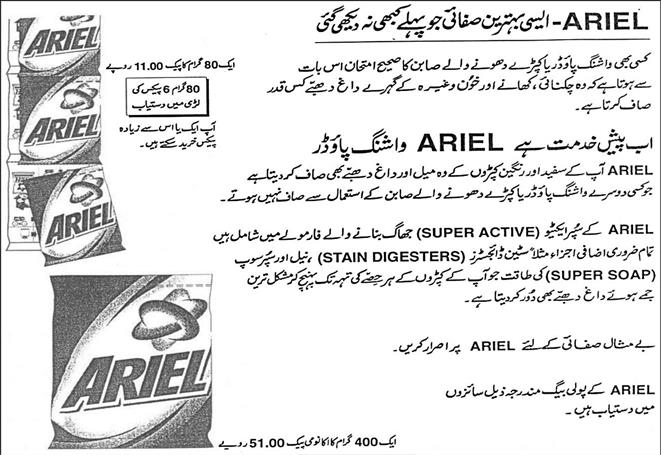

Exhibit 10: Ariel Concept Board.

(Translation)

ARIEL — THE BEST CLEANING EVER

The real test of a laundry detergent or laundry soap is how well it cleans tough

stains such as grease, food stains, and blood.

NOW INTRODUCING ARIEL DETERGENT POWDER

Ariel cleans tough stains and dirt (on whites and colors) that other detergents and laundry soaps leave behind.

Ariel’s super active sudsing formula contains built-in additives such as stain digesters, bluing agent and the power of Super Soap, which penetrate every part of the fabric to remove even the most difficult set in stains.

For impeccable cleaning demand Ariel.

Ariel polybags are available in the following sizes:

One 80 grams bag for Rs. 11.00. Eighty grams bag is also available in strings of 6 bags, and can be purchased as singles or more.

One 400 grams economy pack for Rs. 51.00

Source: Company Documents.

Exhibit 11: Selected Data from Concept Test.

Exhibit 12: Concept Strength and Weakness.

Exhibit 13: Selected Data from After Use Test.

Exhibit 14: Product Strengths and Weaknesses (after Use).

Note: This case was prepared by Professor Ehsan ul Haque and is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Some non-public data have been disguised and some business details have been simplified to aid in classroom discussion.

Acknowledgment: Received written permission for publishing this case in this book from Suleman Dawood School of Business, Lahore University of Management Sciences Pakistan. LUMS own the case.

a. Households were divided into various socio-economic classifications (also see Exhibit 1).