Khandoker Mahmudur Rahman

People see the past, artists see the present, but designers see what could be. Designers are solely concerned with what could be.

—Karim Rashid, Industrial Designer

This chapter examines various decisions concerning the packaging of products: from objective setting to strategic thinking that helps integrate and align packaging decisions with other broader objectives such as positioning, communication, and branding. The chapter also elucidates the variety of tests that packages need to undergo — from visual to technical, consumer, retail, recognition, and related tests. The case examines how convenience provided by plastic bags conflicts with social and environmental degradation, thus affecting broader quality of life issues.

Packaging is the outer appearance of a product. It also serves the basic function of containment and protection. It also dresses up the way it visually appears to customers’ eyes. If the first impression is really important, packaging design must have an impact on customers’ minds.1,2 Apart from its primary role of providing safety and protection to products, packaging plays many secondary, yet extremely important, roles of communication, legal compliance, environmental protection,3 shelf management, promotion, and positioning.4 This chapter will focus on various issues concerning packaging that will help make good marketing decisions.

Picture: Sample of a gift pack (http://www.stockfreeimages.com/4955037/Gift-packaging.html).

Four questions need to be answered to fully address packaging issues in a comprehensive manner. The questions are as follows:

• What are the purposes/objectives of designing the packaging?

• What strategic elements would guide the design choices?

• What materials are being planned or required for packaging?

• How would you test your packaging for competitive edge?

Issues related to these questions will be addressed in a step-by-step process in the following parts.

The most obvious definition of packaging is to design and produce a container or wrapper for a product. Thus, a box or container that holds the product is called the package. A packaged product, for example, a toothpaste tube, can be packed in another box made of hard paper or any other material. These boxes containing individual toothpaste tubes may then be placed into bigger boxes (cartons) by the dozen for easy transportation to wholesalers or retailers.

DEFINITION

Packaging design does not only mean the visual and texts on package, rather the whole gamut of materials used, construction, and final appearance of a package that serves packaging objectives.

Therefore, a package may have three levels. The immediate container that holds the product is called the “primary package.” In our case, it is the plastic tube that holds the toothpaste in it. The tube is put into a box which is the secondary package, because its purpose is to protect the primary package. Secondary package is usually discarded at the time the product is opened for use. However, some products may have only the primary package. For example, children’s toys are often packed in one layer of transparent primary packages which are discarded after getting the toy out of it.

The third or tertiary packaging level is called the shipping package, which is aimed at fulfilling the objective of bulk storage and transportation. For example, hundreds of single toothpaste boxes can be packed in a corrugated carton/box for the purpose of bulk storage and transportation to dealers’ warehouses. Shipping packages are discarded at the wholesale or retail level and does not usually reach consumers.

Evidently, these three levels of packaging will serve different purposes at their respective levels.6 Overall, the purposes of packaging can be sixfold.

(a) Containing the product: This would be the main objective of the primary packaging. It primarily looks at safety, quality, and preservation of the product in the container.7 A toothpaste tube serves this basic purpose of containment. An airtight glass package of orange jelly serves the basic purpose of containing the product. A blister pack of pills contains the product inside its spaces. In many cases, customers are served the product with only one level of packaging, that is, primary packaging. Still others may contain both primary and secondary packaging. Irrespective of the kind of packaging the customers are served with, a package involves labeling that may go with both primary and secondary packaging.

DEFINITION

Labeling is an integral part of packaging. It refers to any written description in verbal language or using a symbol printed on the package. It includes brand name, company name, usage direction, usage warning, side effects, benefits, date of manufacturing, date of expiry, and any other information either voluntarily or statutorily inscribed on a package.

(b) Creating convenience value to customers: This can be achieved both at the primary and secondary packaging levels. For example, liquid soap can primarily be packed either in a bottle with a screw cap or in a container with press pump that will release a drop of soap once pressed by the user. In the second case, primary packaging would be creating higher convenience value than that of the first one. In many cases, secondary packaging may also confer this convenience to customers.7 A glass container of fragrance may be further packed in a cardboard box, conferring easy to store and convenience value to users.

With the rise of pilferage and store-thefts, marketers are continuously using innovative techniques to prevent pilferage or make store-thefts difficult. In many cases, marketers often design their packages with innovative construction and top-notch package sealing technology, suspecting pilferage and/or careless handling of transport and delivery employees. Ironically, this type of pilfer-proof packages and hi-tech sealing can create huge customer inconvenience.8 For example, taking a toy out of a box becomes a nightmare for many parents. Tearing an aluminum foil pack of potato chips by hand oftentimes becomes so difficult that many chips would fly out due to a sudden tear effect. Marketers need to strike a balance between quality objectives and convenience factors when designing packages.

(c) Creating promotional value to customers: Packaging has great communication value through its visuals and labels.4 Customer of a new product first comes in touch with its packaging, even before he/she opens the same to use the product. Customers often read labels carefully before making a choice. Thus, package design has great responsibility of providing the correct mix of brand knowledge to customers. Since customers’ perception of product quality may be influenced by its packaging, a well-designed package with strong visuals and labels would most likely confer the perception of quality to customers. Thus, designers must be careful of the theme and color choices of visuals and selection of labeling that address customers’ cultural preferences and interpretations.

To increase promotional value to customers, many designers may choose to provide packaging inserts (PI) inside a package. PI refer to leaflets, booklets, instruction manual, or other types of inserts that are included in a package for various reasons. Most of the time, they are inserted into the secondary packaging along with the primary packed product. These inserts may include indications, adverse effects and dosage directions (for medicine), operating manuals (for household appliances), warranty card (for claiming warranty services), additional promotional information (like discount cards or coupons), exciting information that would create value to the product (attractive cook book with a microwave), or related information of value to customers. PI may also be aimed at lowering cognitive dissonance (feeling of discomfort due to risk involvement in buying a product) by providing information that would ease customers’ worries.

The display value of packaging through theme, color choice, and labeling has great impact on identity and differentiation of a product in the minds of customers.9 For many products showing variety-seeking buying behavior (i.e., low-involvement products, yet high differences among brands), designers tend to change the package design every four to six months to give customers a “new” feeling. It helps to promote a continuously differentiating image to customers, even though there might not be any actual change in the product. This image aspect of packaging impacts brand management of products in a marketers’ portfolio.10

(d) Creating value to retailers: Retailers need to store and display products on their shelves for future sales. Three key values that packaging should confer to retailers are (i) storage convenience and value for efficient shelf management, (ii) preservation of quality while it is stored, and (iii) communication value through display.

Retailers are wary of available shelf space because it is limited, no matter how big they are. Thus, a package must confer storage convenience to retailers.11 For example, most ice-cream sticks would be preserved in retailers’ refrigerator not in the primary package, but in the secondary package of cardboard boxes. A dozen ice-cream sticks, if stored individually, would take more space (and would look cluttered) than a cardboard box containing a dozen sticks. It would also be easier for the retailer to pick up a stick when dispensing this to customers. This space and dispensing criteria are well addressed by most contraceptive products that are sold through pharmacies or general stores in Asian countries. Most of these products are bulk-packed in a convenient secondary or tertiary package that can be hung on a nail in the wall, and individual packages can be pulled out and dispensed to customers on demand.12

Other than storage convenience, a retailer would also be interested to evaluate the per-square-foot potential return of a product. Unless the product portfolio yields maximum possible profit from shelf space use (in terms of turnover times profit percentage), this space would be underutilized and opportunity to profit wasted. Therefore, in terms of profit and pace of sales, packaging design must consider its size (amount of space it would grab in the shelf) and profit percentage expected out of it. Both primary and secondary packaging should look into retailers’ value requirements. Maximizing the value to retailers is the key here.

Packaging must also ensure that product quality is maintained until the expiry date printed on the package. Here comes an important issue of labeling, which is an integral part of packaging. Choice of packaging materials, both at primary, secondary, and shipping levels, are of great importance to ensure preservation of quality while stored. Customs, practices, and environment of storage at retail and wholesale levels must also be considered while designing packaging. Products require a special type of preservation environment, for example, certain medicines requiring refrigeration should not be sold and stored to retailers not having the storage facilities. The same applies to milk, ice cream, and other frozen items where refrigeration and supply of electricity are unavailable. Many marketers can create value to retailers by reducing storage cost. For example, ultra high temperature (UHT) treated milk can be stored without refrigeration for months.13

In many Asian countries, on-site sales of certain commodities like sugar, lentils, salt, etc., take place through retailers scooping out portions of the commodity from bulk-packed jute/poly sacks. The scooped-out portion is weighed (usually in kilograms or grams as per customers’ requirement) and instantly packed in makeshift paper packs, just enough for delivery and carrying convenience to customers. The original bulk sacks are often designed keeping in mind the space available to retailers, as well as convenience to retailers and distributors for ease of transport. On the other hand, in line with packaging convenience to retailers for this type of bulk-breaking sales, third-party producers of hand-made empty paper packs are doing great business with retailers. These producers mostly produce makeshift packs from recycled paper, primarily from trash paper collected from offices and other institutions. This is an example of how a supply chain is profitably sustained in order to deliver convenience value to retailers.

Storage by retailers for the purpose of sales necessarily calls for displaying the product on shelves. Retailers often prefer attractive packaging due to its display value. Quality of packaging often confers quality perception of products to customers. Retailers understand this perceptual part of customers well. In turn, they also prefer packaging that would look good on shelves.14

In order to maximize display value to retailers, a designer must survey the existing package designs of its competitors in the market. Designs similar to competitors’ designs would not only confuse customers but also reduce unique display value to retailers. Visual presentation along with appropriate labeling would serve the purpose of display by creating communication value to retailers. A well-designed packaging with proper labeling would make the retailer’s job of communicating to customers an easy one. Thus, theme and color choice of packaging (including labeling) would be extremely important to create this unique display value. In many Asian countries, in line with customers’ quality perception, based on attractiveness of packaging, retailers may prefer bright-colored packaging that would not fade while stored for sale. Marketers often avoid white color in packaging (unless on glossy paper) due to the possibility of collecting dust and moisture on packaging from the typical Asian climate.

Tips In general, original work of art, be it in visual or text, automatically gets copyright protection once it is created, whether published or not. However, it is recommended to file for copyright protection to respective regulatory department, for stronger legal position in possible future dispute. On the other hand, patent rights are not automatically derived. One must file for patent protection which will be verified and approved by the concerned authority for trademark, copyright, and patents. For further information on Intellectual Property (IP) rights, visit http://www.wipo.int

(e) Complying with legal issues: Most countries have their own packaging and labeling laws. In general, packaging laws include, but are not limited to regulations of food and beverage packaging, tobacco packaging, pharmaceutical packaging, hazardous material packaging, consumer protection issues, consumer safety issues, and environmental issues. Many countries regulate deceptive packaging, use of certain materials in food packaging, labeling requirement in tobacco packaging,15 requirement of recycling, etc. Legal compliance issues may affect primary, secondary, and shipping packages, depending on the laws and regulations of countries concerned.

Recently, Australia became the first country in the world to legislate all tobacco products to be sold in plain packages.16 Since packaging is considered the frontline of advertising, the government has severely restricted companies’ ability to promote tobacco products to consumers. Companies will not have much choice regarding the visual, warning, and overall design of the package.17 The only thing they can put out is their brand name. The law requires that companies put vivid visuals on the front side of the pack, for example, a cancerous lung, a cancerous mouth, a leg with ulcers, etc. The visual must be complemented by verbal warning that tobacco usage leads to these types of illnesses to consumers. Below the visual and above the bottom end, the brand name will appear in small fonts. Since all brands have to design packages in the same way, the only way to find someone’s favorite brand is to look at the brand name below those visuals. This development is expected to start a new wave on tobacco packaging not only across Asia but also across the globe.

Some countries have mandatory requirement to label certain products with their national marks. Products need to be submitted to designated laboratory for testing and certification.18,19 Upon passing the certification requirements, permission is given to use standard certification mark on its packaging.16 For products requiring mandatory certification, it is illegal to sell those products without certification mark on its packaging. In most cases, once certified, the national standardization and certification body would randomly check packaging and quality of the product available in the market and review the use of certification marks on those products from time to time. Food products are the most common across Asian countries that require mandatory certification, although the list of products of individual countries may vary widely.

Another important legal aspect of packaging concerns trademark, copyright, and patent issues. Copyright is about rights to any artistic work on packaging, including but not limited to visuals, texts, color combination, symbols, etc. On the other hand, patent is about rights to innovation or original invention in the process and/or the final package construction. For example, brand name, logo, texts, color combination of design, etc. may require trademark and copyright protection. On the other hand, if you construct a unique packaging, for example, a unique hexagonal packaging for candies, it might be protectable under patent laws. Many fast food chains serve potato fries and burgers in special boxes that are patented for their style of construction.

(f) Sustainability objective: Sustainable packaging may be defined as a packaging process where materials, process, and functionality of the package is based on optimized use of renewable energy, environment friendly materials, and low-carbon footage in its life cycle, resulting in eco-friendly packaging.

While packaging serves very important purposes, not all of them are harmless to the environment in the long run.20 Plastic packages, in particular, end up as trash that ultimately find their way to landfills. With growing population and dwindling agricultural land in Asia, the increasing need for landfill sites is not a good phenomenon. On the other hand, most plastic packages currently used in Asia are either not recycled or not biodegradable. In addition, due to littering of packages, not all packages necessarily end up in landfills. Many packages would be thrown out on streets, drains, and water bodies around town. Plastic packages would not only block drainage systems but also take hundreds of years to degrade in the environment.

Rather than making more and more packages to throw out and send to landfills or block drainage systems, marketers need to find alternatives that would be sustainable in the long run. Some responsible marketers are already working toward incorporating environment friendly packaging in their product line, thus creating “green value” to customers and other stakeholders.21 In some cases, this sustainability objective might be mandatorily addressed because of statutory reasons or could be done voluntarily due to the company’s strategy to project itself as a responsible and sensible green marketer to its stakeholders. For example, many food manufacturers would use biodegradable plastic to pack their food items in order to project themselves as marketers who care about the environment. Still others would use recycled materials in their package, if not biodegradable materials, expressing themselves as environmentally concerned companies.

However, exploitation of consumers by unjustifiably labeling a product as “green” is also not uncommon.22 For example, an organization may falsely claim that its products are green because it uses recycled paper in packaging. It does not say that the product inside the package is actually green. This sort of perceptual manipulation is called “green washing.” Although a claim by a green brand may not be outright false, a self-claimed proposition is oftentimes doubtful unless verification and certification are received from an authentic third party certifying agency for the purpose.

Some countries have green certification agencies that evaluate and certify products that meet environmental standards. These marks and labels for certification are called “eco-labeling,” which oftentimes act as promotional signs and a matter of pride for brands.23 Even though eco-labeling is primarily given to products, an eco-friendly packaging is a must for this certification to be achieved.

Eco-labeling It is a method of environmental performance certification and labeling that is practiced around the world. This is expressed in terms of government or private sponsored markings, popularly known as eco-seals or green seals. Some popular green seals are “Swan” (Norway), “Energy Star” (USA), “Green Seal” (USA), and “Blue Angel” (Germany).

Once the sixfold purposes of packaging are identified, the next step is to align these objectives with strategic elements while designing a cutting-edge package.

Since packaging is at the frontline of brand communication, it has great promotional value to marketers.1,4 Besides all the functions as elaborated in the previous section, the ultimate task of packaging would be zeroed-in on effective “positioning” of the brand. Positioning is about placing a product in customers’ minds. It is not easy to do so in the fiercely competitive markets of today. The challenge of positioning lies in getting into customers’ minds amid a competitive market where other brands are also fighting to attain mind share. Cutting through this clutter requires creativity and alignment with customer insights to achieve effective brand associations through differentiation.

Therefore, positioning strategy should ultimately guide packaging design. In turn, it is important to consider the profile of the target market segment(s) while choosing visuals and texts on packaging. Understanding the desired image would also be important while choosing the theme and color combination in order to create positive association in customers’ minds. In other words, it requires that marketers evaluate their differentiation proposition, through which they would be attaining the positioning objective, so that the proposition is sufficiently reflected and communicated in overall package design. In many cases, differentiation is based purely on image, thus special packaging could be the only source of differentiated perception in customers’ minds rather than the actual technical or functional superiority of the product.24 Apart from ethical and legal questions as to whether such packaging would be susceptible to deceptive packaging laws, many products are already using this packaging approach and getting away with it. The ultimate challenge is that the final design must stand out in the crowd, creating relevance and value for all stakeholders in the process (customers, retailers, regulatory bodies, and the organization itself).

Since the desired positioning would be the prime guiding factor for packaging design, it is important that packaging be considered as a part of integrated marketing campaign of an organization. The current use of media, storyline, advertising copy, sales promotion, etc., could warrant reflection of the same on packaging design. Many products would change their packaging to reflect special discounts or bonus offers, aligned with campaigns in various media.

In line with branding objectives in packaging, brand association and positioning have to be consistent over time. However, it does not mean that the same mix of differentiation propositions has to be used repeatedly to accomplish this. On one hand, competitors would gradually copy differentiation proposition and the advantage would be reduced. Thus, differentiation is not a one-time task; rather it is a dynamic one that requires modification over time in order to gain an edge over the competition. On the other hand, apart from differentiating in relation to the competition, marketers need to differentiate based on insights of the most important players in the market: the consumers! Marketers must constantly monitor change in tastes and preferences of customers to spot shifts in customer insights. Changes in tastes and preferences may require modification of the differentiation proposition to be reflected on packaging design. In many cases, even though there might not be any change in customers’ taste and preferences, marketers may intermittently change packaging design to yield a fresh and new feel to customers, thus attempting to create an edge over competitors.25

Consistency and dynamism should also be attained in line with the tentative position of the product in its life cycle. Introduction, growth, maturity, and decline stages pose different challenges to brands. Packaging design should be dynamic enough to accommodate life cycle challenges and reflect changes through redesigning when necessary.

Choice of packaging materials are important for functional, cost, legal, technical, and positioning objectives. The following objectives could be focused on while choosing packaging materials:

• Functional objective (safe containment and transportation, preservation, quality maintenance)

• Cost objective (minimizing cost through appropriate material selection)

• Legal objective (regulatory compliance)

• Technical objective (technical feasibility of materials to support other objectives)

• Positioning objective (whether the chosen material would yield design that would fit with the image and promotional value, including sustainability issues).

Ideally, materials should be selected by meeting all the criteria as mentioned above; however, certain level of compromise is expected due to various reasons. For example, packaging of food by regular grade of plastic may be technically, functionally, or costwise feasible. However, food must be packed in food-grade plastic in most countries due to legal requirements. Some countries require that recycled materials, along with biodegradable materials of plant origin, must be used in packaging of certain items like beverages. For example, in Denmark, it is required that packages contain 50% of recycled plastic and 15% of plant materials. However, in the United States and Canada, 30% of plant materials is necessary instead of 15% as in Denmark. Legal requirements of biodegradable materials may often result in increase of packaging cost, which is unavoidable unless other nonplastic materials are used.

Issues surrounding packaging materials would be faced most in food and beverage packaging, due to stringent legal requirements in many countries. Some materials might be susceptible to leeching harmful chemicals into foods, for which food may be contaminated after getting in touch with the package for some time.26 Use of quality color on packaging must also be carefully ensured, otherwise dyestuff may also leech, resulting in contamination. In some cases, food itself must be treated in special ways so that they stay fresh inside the package. For example, nitrogen flushing of foods (particularly some snacks) keeps the food fresh inside the pack. Even though nitrogen may not be considered as a packing material per se, it serves and enhances an important packaging function.

From international trade perspectives, certain packaging issues could pose as Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) concerns. TBT includes nontariff barriers (NTB) or nontariff import bottlenecks. Since the rationalization of tariff structure on a global scale under the continuous initiative of International Trade Center (ITC) has led to either abolition or rationalization of high-tariff structures across countries, governments seek innovative ways to prevent or reduce imports by means other than tariff barriers.

Nontariff barriers could include, but not limited to countervailing duties, quota, safety inspection requirements, administrative red tape to slow down imports, unrealistic or discriminatory packaging and labeling requirements by the importing country, etc. In many instances, there are legitimate and valid causes (e.g., preservation of quality and safety of the product) of imposing these requirements on exporting countries, which may be allowable under existing TBT Agreement, signed by member countries of ITC. However, importing countries often put these restrictions under disguise of legitimate causes which ultimately act as barriers to the exporter. For example, if country A requires that country B use special category of expensive wooden packages for exporting books to A, to be transported through land carriers, whereas the same regulation does not apply to domestic packaging and land transportation of country A, this requirement may make country B’s export expensive and uncompetitive in country A while serving no legitimate purpose; it is also discriminatory for country B. There is a good chance that if country B files dispute to ITC, the ruling might go in her favor, asking country A to withdraw such packaging requirement.

Apart from technical aspects that are related to regulatory requirements, there are other technical criteria for choosing packaging materials so that the package performs its primary and secondary functions effectively. Particularly for shipping packages, materials must be carefully selected that can endure drops, vibration, shocks, jarring, etc., caused during handling and transportation. Primary and secondary packages are also important because they must ensure that the product would be safe and intact while it stays in the pack. Many hazardous products are packed using materials that would not react with the product itself.

Positioning objective would also be of immense importance while selecting packaging materials. For example, while it may be feasible to pack fruit jelly in Tetra Pak®, it may not fit with the positioning idea because this is quite uncommon for this category. Fruit juices and related beverages popularly use Tetra Pak® in Asia, and packaging of juices helps to reinforce the product identity due to familiarity. Similarly, where the brand claims to be eco-friendly, using recycled materials in its packaging would surely reinforce the positioning idea of the brand. The same applies to products having aesthetic appeals. For example, jewelry packaging is noticeable with their unique gift-like package with hinges and locks. Some of them will have transparent tops so that the design of jewelry can be seen even when the product is inside the pack.

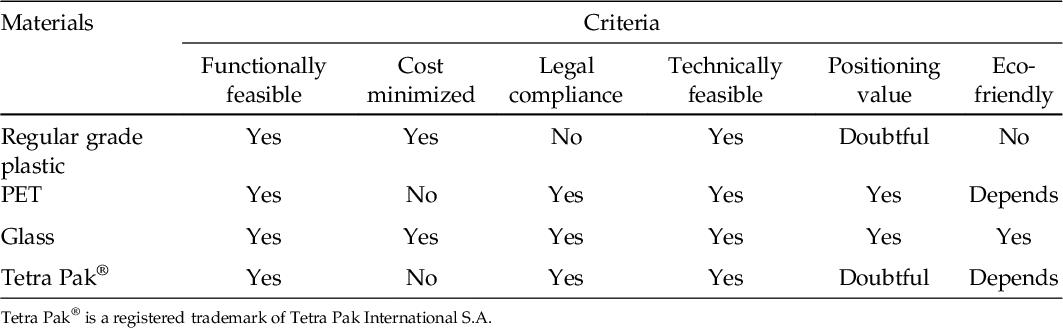

In order to evaluate the feasibility of packaging materials, a check sheet for packaging fruit jelly is given in Table 1. The marketer may require further inputs from technical team to evaluate material options for product-specific packaging).

Table 1: Evaluation Summary of Glass, PET, and Tetra Pak® for Fruit Jelly.

Based on the evaluation summary on the check sheet, the marketer may consider the option of using glass as packing material, unless more criteria are added to evaluate these options further.

Packaging design must go for multilevel testing before it hits the market with the product contained within. In many cases, package testing continues even after successful launching of a product. Some products, for example, food, pharmaceuticals, dangerous goods, or medical devices require mandatory testing of packaging by regulatory bodies in most countries. For unregulated products, package testing can be voluntarily done in order to minimize risk factors associated with the product or process. Risk factors include the safety and integrity of the product, value of the content, value of customers’ goodwill, legal liability due to package failure, and any other costs related to package failure. In certain cases, unregulated products may be subject to package testing if required by a contract of export, contract of sales to business buyers or government. Packaging failure is abundant, thus being careful at the beginning would save marketers money, image, reputation, and litigation.

Three broad categories of testing need to be done for packaging. They are27 visual testing, technical testing and consumer testing. These tests are elaborated below.

Visual testing: This is an important category of testing from the communication point of view. Visual testing is about evaluating the visual value of a package design and its impact on dealers and consumers. Thus, visual testing can be of two types: visual testing at the dealer level and visual testing at the consumer level. Three perspectives of visibility may be tested in visual testing: the visibility of the package when stored at retail, noticeable differences from other packages when stored, and clarity and impression of texts and design to consumers.

A retail store usually places items of similar category together. This represents a challenge for packaging to be clearly visible. In addition, retailers’ feedback of their likes or dislikes about the visual aspect of packaging is also important. Retailers want to keep their stores attractive, thus attractive packaging is often displayed in most visible places at retail stores. Winning the support of dealers on visuals is a crucial step in getting premium shelf space. This is one of the reasons why many marketers intermittently change packaging design to keep a “new & fresh” image among dealers and consumers. Besides visibility, making a package stand out among the competition is also important. A mere “visible” package does not necessarily mean that you can tell the difference with other competitors’ packages. Visibility must be ensured along with identifiable differences with competing packages.

A package has to be visually appealing to the most important stakeholder: the customers. Is the text in the packaging clear? Is there too much text, cluttering the message in the packaging? Is the visual design attractive and appealing to customers? How about color choices and visual themes? Are they in line with the target customers’ tastes and preferences? A packaging design must test these questions at the consumer level.

Technical testing: Technical testing is aimed at meeting engineering specification of the package.26 Its purpose is to ensure proper materials, construction, durability, usability, and safety that should result in attaining packaging objectives.28 Technical test can take place at two levels: laboratory level and field level.

Laboratory testing may comprise of packaging material testing and package performance testing. It is based on the assumption that packages go through different levels of strain depending on the chosen mode of transportation and climate. Air, sea, railroad, and roads impose different types of stresses on the package, specifically on the tertiary or shipping package. In many cases, stress on shipping package may damage the secondary or primary package. Even if the primary package stays intact, a product with damaged secondary package is hard to sell to customers, thus increasing the probability of damaged returns from retailers. Therefore, tests for package performance are aimed at evaluating whether the package design is able to endure the normal highest possible wear and strain during transfer from source to destination28 and during storage at retailers’ ambient environment.

Laboratory tests include evaluation of package performance in terms of declared shelf life of the product. Different materials may yield different shelf-life scenarios for a product, thus leaving companies with choices to balance cost, functionality, and compliance issues in packaging. Laboratory tests may also include strength testing of shipping packages to endure stacking pressure from other similar packages above it. For example, depending on the size of shipping boxes, the manufacturer may label the limit of how many shipping packages can be vertically stacked over each other. Fragility of products adds another dimension to strength tests. For example, performance of packaging materials inside packages (e.g., protective foam for electronics goods) may be tested for their ability to protect fragile products contained therein.

Apart from physical strains as noted during transportation, some packages may need to be protected from fading due to frequent handling and adverse weather conditions. Some packages may be produced from glossy paperboard or from paper coated with special polymer so that the packaging does not look faded from strains of frequent handling and adverse weather. Many pharmaceuticals are packaged to prevent sunlight exposure in order to retain quality. Therefore, two broad categories of strains are mechanical strain (like rolling, dropping, lifting, acceleration, shocks, jarring, etc.) and climatic strain (like rain, bright sunlight, dust, moisture, snow, etc.). Various tests are designed to consider these criteria and see whether the package satisfies these standards.

Besides performance testing of packages for transportation and shelf life, packaging materials also need to be tested to ensure functionality and legal compliance. Like packaging tests for physical strain and climatic tolerance, packaging materials can also go through physical or mechanical tests and chemical tests. For example, plastic materials can be tested for their mechanical properties like abrasion resistance, heat shrinkage, impact resistance, etc. On the other hand, Chemical tests are aimed at testing chemical properties of plastic, requiring different kinds of tests unlike physical tests. For example, Food and Drugs Act and Regulations, Canada, prohibits the sale of food in packages that may impart harmful substances to their contents. Thus packaging materials must go through chemical tests to ensure that the materials (primarily plastics) do not contain any contaminants that would leech into the food when packed.

Laboratory tests may also include customers as subjects in some instances. For example, Poison Prevention Packaging Act (PPPA) of the United States specifies how to use a panel of children to test “Child Resistant Packaging.” For a package to be qualified as child resistant, 80% of children (of predefined age range in the law) tested must not be able to open the package in a 10-minute test as prescribed in the Act. However, it must be easy to use by adults as well. The Act also requires that 90% of adults tested must be able to open the pack in a five-minute test, and another one minute to close the pack so that it becomes child resistant again. Using humans for the purpose of testing packages in a laboratory environment is nothing new. In many cases, laboratories may perform organoleptic tests, a kind of simple test using human senses of taste and smell to determine if packaging materials might have transferred tastes and odors to the food or pharmaceutical products. Specifically, when not packed in food-grade plastics, food may smell like burnt plastic due to odor migrating from the packing materials. This is not only illegal but also reduces product appeal and image to customers.

Field testing is aimed at measuring and evaluating actual performance of the package at various points including packing, transportation, and transfer to end user. While laboratory experiments have certain advantages, for example, replication of actual environment in a controlled process, it has certain limitations of practical validation as well. Field trials serve the purpose of measuring and validating laboratory results with that of the actual performance environment. Real environment has higher variability and includes unforeseen circumstances compared to the laboratory environment. A package, on average, might go through different magnitude of mechanical and climatic stress as compared to that of controlled laboratory environment. Field trials thus serve as an important source of feedback to ensure that package designs perform well in real situations.

Consumer testing: Packaging objectives at customers’ level could be easy identification, communication of unique proposition, product image, positioning, easy selection by consumers, communicating new benefits, communicating brand knowledge and brand association, standing out in competition, re-branding, etc. We have already covered a little part of consumer testing while going through “visual testing” and technical testing (child-proof packaging). Visual tests are a preliminary evaluation of overall visual value of a package. Consumer testing can further be extended beyond mere visual tests to fathom more critical issues larking behind consumer psyche around packaging.

It must be evident that package design includes not only visual and text design, but also selection of materials, construction, and final appearance of a package that would serve packaging objectives. Since designing a package is partially an art that is combined with a sense of business and customer insights, consumer testing necessarily evolves and validates the cultural perspective. Results obtained under one cultural perspective may not be applicable to another culture without repeating the test in the new one. Therefore, the basic idea around consumer testing is to measure and evaluate whether package design has been able to achieve its objectives at ultimate stakeholder’s level, that is, customers.

Consumer testing is usually undertaken via qualitative research, administered in focus groups. This may reveal important feedback on whether consumer-level objectives are met or not. Some of the most used consumer tests are elaborated below.

Attitude testing: A designer may measure extent of liking or disliking of package attributes using a qualitative scale in a focus group. Attitude testing can take the form of ranking of different attributes like visual designs, text contents, color choices, shape, user friendliness, product expectation, etc. of a package. Consumers can rank attributes in a Likert-type scale where attitudes to different design options can be measured by the designer. Attitude testing can yield important feedback to designers about customers’ preferences on various design dimensions.

T-scope testing: T-scope or tachistoscopic test29 is a simple packaging test aimed at measuring the speed of recognition of different package designs by the consumer. In this test, the consumer is shown a collection of packaging designs at brief time intervals, usually fractions of a second, then consumers are asked to identify whatever was seen by them. It assumes that the design identified in the quickest manner has the highest probability of actual success in the market. The major disadvantage of this method is that it assumes fractions of a second to be sufficient for a consumer to recall the most impressive design. Although a T-scope test could be valid for measuring attraction, real results might be more complex in field situations, depending on branding of products and thought processes of consumers. The test confers a higher chance on the part of consumers to identify known brands rather than new brands. Therefore, a new design would hardly come out successful using tachistoscope method. Despite all these limitations, T-scope test can yield important feedback as a one-shot measure of package attractiveness.

Findability test: Findability test simply measures the ease with which a consumer can identify and locate a specific package on the shelf. In this test, consumers are asked to find specific products, through packaging identification in a cluttered in-store shelf space scenario. Ease of locating a package on the shelf is of immense importance as many studies across the globe found that, on average, two-thirds of in-store purchases are unplanned. Thus standing out in the shelf would increase the probability of being picked-up by consumers.

There is a concern that asking a consumer to find a brand that he/she is looking for would be relevant to one-third of consumers since this is the group whose purchases are planned, and they are going to find their preferred brand anyway. Evidently, researchers need to look into how the rest two-thirds of consumers find, with varying degrees of ease, different packaging designs. Therefore, the test assumes that the design that increases the ease of finding a package on the shelf will have better chance of success in a real store.

Recall question: Recall research is often used in advertising research. For package testing, consumers may be introduced to a shelf scene and later their recall rate of the various packages could be tested. The main limitation of recall questioning is the problem of familiarity. Established brands get higher recall rates in this test, thus it obscures the actual value of a new package design on the shelf.

Eye tracking: Eye tracking is a behavioral research for package testing. It attempts to measure the noticeability of the package on the shelf among competing brands and helps to determine the aspects of packaging to which consumers pay attention on. It also tracks the path of eye movement on the shelf, monitoring what customers prefer to see or simply ignore.30

It uses a device called “eye-tracker” that monitors a respondent’s sight. This device generates infrared light at a safe level, which when reflects in the respondent’s eyes, returns signals that are captured by a sensitive camera. The eye movement on the shelf thus gets recorded and is later analyzed to determine which packaging was most noticed by consumers. Notice the ability of visuals, texts, or any other aspect of a particular package can also be analyzed through this test.31

Test market auditing: Test market auditing is done at the field level once the product is actually launched with a final package design. Oftentimes, it takes a smaller test market to measure the real response of consumers before the product can be launched on a larger scale. Real responses from a small-scale test market can yield important feedback that may lead to product or package modification before the actual launch.32 This would help marketers avoid expensive redesign, and save time and money in the long run.

A summary of important issues in package design is provided in Table 2.

Table 2: A Comprehensive Checklist for Packaging Design.

Focus |

Issues |

Methods |

Objectives of packaging |

Effective containment and safety, value creation for customers, communication to customers, value creation for channel members and other stakeholders |

Primary packaging, secondary packaging, tertiary/shipping packaging, use of technology, visual appeal to stakeholders, labeling |

Strategic design elements |

Differentiation, brand association, positioning, product life cycle, communication value, shelf management |

Selling proposition, elements of brand association, visual design, segment analysis and life cycle adaptation, creation of promotion value to stakeholders |

Package construction and materials |

Functionality, cost efficiency, legal compliance, environmental issues, positioning objective |

Functional, technical, economic, legal, environmental, and positioning feasibility studies; Alternative package costing |

Package testing |

Validation of strength and primary functionality of packaging, validation of communication value to stakeholders |

Attitude tests, T-scope tests, findability test, recall questioning, eye tracking, test market auditing |

CASE: PACKAGING

Plastic Shopping Bags in the Bangladesh Context

Khandoker Mahmudur Rahman

Plastic shopping bags offer a huge convenience for shoppers. Light, strong, handy, waterproof, cheap — all these qualities can be attributed to plastic bags, popularly known as polythene bags. Apart from convenience and cost factors, these bags have been a nuisance not only for Bangladesh but also for the world as a whole. It clogs drainage system, slows sewerage lines, aggravates urban flood, takes up area in landfills, poses risks to animals, damages soil, and takes about a thousand years to degrade in the environment. Let us take a closer look at this problem.

In a survey by the European Commission, it was found that every year 800,000 tons of single-use plastic bags are used in the European Union. That means European Union citizens used, on average, 191 plastic bags in 2010 and only about 6% were recycled. In numbers, more than four billion bags are thrown away each year. According to the Commission, the result of this plastic waste is littering the landscape, threatening wildlife and accumulating as “plastic soup” in the Pacific Ocean, which may cover more than 15,000,000 square km, mostly during the past 30 years.

In South Africa, they are satirically dubbed as “national flower” because so many polythene bags can be seen caught in fences and bushes. In North America, use of plastic bags is also very high. It is estimated that every four out of five grocery bags handed to the US customers are made of polyethylene. Americans throw away almost 100 billion plastic bags every year and only about 7% are recycled.

In India, cows have often choked to death by ingesting plastic bags while grazing or looking for food in the streets. Plastic bags often are stuck in an animal’s stomach and cause death. These bags are also of danger to other aquatic animals, such as turtles which commonly mistake plastic bags for jelly fish. An estimate shows that about 1 million birds, 100,000 whales, seals, and turtles, and countless fishes worldwide are killed by plastic rubbish every year. In April 2002, a whale was found stranded on a beach in France with approximately 2 pounds of plastic debris inside its stomach.

Plastic bags were found to constitute a significant portion of the floating marine debris in the waters around southern Chile, which poses great risk of strangulation and choking hazards to aquatic being. In other cases, where bags stay within cities and do not make their way to landfills, they get into the drainage system to create a different kind of problem. Clogging of drainage system by plastic bags was identified as one of the main reasons of annual flooding in Manila, Philippines. The same applies to floods of 1988 and 1998 in Bangladesh, which submerged two-thirds of the whole country. Shopping bags are not only harmful when littered, but also when this is produced. This is a petrochemical product, requiring gas or oil as its sources. Thus its production process pollutes the environment and emits greenhouse gases. Burning of shopping bags, in order to get rid of them, can also pose other dangers by producing Dioxin and Furan, two highly toxic chemicals that are emitted to environment.

In view of this grave environmental menace, antiplastic sentiment of the general public and policy makers alike is noticeable across the globe. Much debate went on across countries on what to do about this problem of shopping bags. Some recommended a ban, some saw success by raising taxes on shopping bags, some regulated usage behavior along with taxes opportunities. However, critics argue that the problem is not with the shopping bags, but with human behavior of littering. Had all these shopping bags not been thrown out on streets and garbage bins, they would not make their way into landfills, drainage systems, and to the sea. They argue that, “banning” shopping bags is not a solution, but “managing” is. People need to stop their littering behavior and be responsible by helping in recycling plastic bags.

Littering problem is usually grave in developing countries where there is a lack of proper infrastructure for recycling. Lack of consumer awareness could be another dimension added to the problem. Compared to 6% of plastic bag recycling in the European Union, and 7% in the United States, the recycling situation does not seem very promising even in developed countries.

Faced by the alarming consequences of plastic bags on the environment, countries adopted their own strategies to fight the menace. Four broad categories of measures are evident, which are either adopted independently or in conjunction with other measures depending on the country concerned. These measures are (i) encourage and/or statutorily require use of recycled plastics, (ii) impose tax and/or statutorily charge a price for plastic shopping bags to customers to discourage use and encourage reuse, (iii) encourage and/or statutorily require biodegradable shopping bags to be used, (iv) complete ban or conditional ban on plastic shopping bags.

Option 1:

While nothing prevents a country to adopt all these measures simultaneously, different countries adopted different sets of options depending on their agenda and constraints. For example, in the United States, Rigid Plastic Packaging Container (RPPC) Act (1991) of California requires that every RPPC offered for sale in California meet one of several criteria designed to reduce the amount of plastic being dumped on landfill sites. The RPPC law requires the producers of specified packaging sold in California meet minimum recycling criteria, including the utilization of not less than 25% recycled content. Nationwide, use of recycled plastics specifically for food packaging is not mandated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, the government issues directives and guidelines on what to be done in case manufacturers intend to use recycled plastics in packaging.

In order to completely understand the environmental impact of packaging and its recycling, the analysis of the impact of only the final product is not enough. It is important that the total process, starting from the production/procurement of raw materials till the final outcome, should be analyzed through impact measurement. This is called the “Life cycle Analysis” (LCA) through which a clearer picture can be gained. From this perspective, the advantage of recycling is obvious. As already noted, plastics are less of a problem than of the littering behavior of consumers. Shopping bags are prevented from being thrown out in the environment and thus stay within the consumer usage cycle. These plastics are easy to melt, require less energy than recycling paper, and have overall less carbon footage in their life cycle than paper bags. Paper bags require cutting of trees which negatively impacts the environment. This has been a strong argument in favor of recycling plastic bags, and not using paper bags.

There is a problem with plastic recycling though. It is not as repeatedly recyclable as glass, paper, and metal cans. Technically, use of virgin materials in plastic packaging is almost unavoidable, only the percentage of virgin material required can be reduced by using recycled plastic with it. When glass, paper, and cans are recycled, they become similar products which can be used and recycled over and over again, although paper recycling has higher carbon footage than plastic recycling. On the other hand, there is usually only a single reuse of recycled plastics. Most bottles and milk jugs do not become food or beverage containers again. Milk containers are often made into plastic lumber, recycling bins, toys, etc. Bottles might be recycled into synthetic carpet or stuffing for sleeping bags. Recent advancement of technology has enabled 100% recycling of bottle; however, cost effectiveness is still a big issue. There are claims by experts that the environmental impact of the bottle-to-bottle regeneration process is quite high in terms of energy use and production of hazardous by-products. Until the development of appropriate technology, recycling may not be a viable long-term strategy to fight the plastic menace. It can only reduce the plastic menace for some time, only to resurface later in some other form in the environment.

Option 2:

Another option could be to raise the price tag of plastic usage, discouraging consumers to use plastic bags from an economic point of view. The Republic of Ireland introduced a charge of 15 euro-cents per bag in March 2002, which led to a 95% reduction in plastic bag litter. Within a year, 90% of shoppers were using long-life bags. The levy was raised to 22 cents in 2007, after evidence showed that the number of plastic bags used annually had risen from 21 per person immediately after the ban to 30 (compared with 328 per person before that levy was imposed). Through this measure, the government raised about 75 million euros from the levy that was put into an Environment Fund for reducing waste or researching new ways of recycling. Spain, Belgium, Germany, Norway, and the Netherlands are other countries that followed Ireland’s lead with success.

Raising the price tag has certain advantages. Consumers rationally start reusing shopping bags, thus reducing litter. It also raises much needed funds for the government to invest in research and development. However, it does not eliminate the problem completely. With passage of time, the price needs revision otherwise people would start increasing the usage of plastic bags after getting used to a certain price tag. The best part of price imposition could be the government’s long-term effort to innovate better ways of recycling or material research for shopping bags.

Option 3:

A third option would be to encourage or statutorily require the use of biodegradable shopping bags. There is a vast array of products of various technological origin of what biodegradable materials actually mean! Broadly speaking, there are three types of biodegradable bags: the first kind is made of regular plastics with biodegradable additives in it. These additives quickly degrade the bag in the natural environment and make the bag “disappear” by quickly disintegrating into small pieces in the soil. The second type is made of plastic of plant origin that can naturally degrade in the environment. The third type could be made of already available biodegradable materials, like paper or jute.

The first kind has the advantage of technological ease and cost efficiency. Mere mixing of biodegradable additives into a regular batch of melted plastics would do the job! However, even though these bags will not clog drainage systems or take up space in landfills, these bags will leave additives and small plastic pieces as ultimate pollutants in the environment. Therefore, notwithstanding its biodegradability, these bags are just a different kind of pollutant for the environment.

The second type of biodegradable bag is made of polymers of plant origin. Plant starches and cellulose are processed to make recyclable plastics. These often include potato peels and plant cellulose from various origins. The prime advantage of these biodegradable bags is that these are completely degradable without any major pollutant getting into the environment. The biggest disadvantage is the cost and access to technology. While many developed nations can afford to offer these bags for sale to consumers, it would be difficult to do so in low-income developing countries. Until technology can provide a cost effective solution, which seems possible in the near future, plastics of plant origin seem feasible for consumers of high income only.

The third type of biodegradable bags could be made from already available materials like paper, jute, or cotton. While paper can be strengthened to offer plastic-like utility, the LCA clearly shows why paper is not an environment friendly product. First, it requires cutting trees to make paper. Second, recycling of paper requires more energy than recycling plastics. The carbon footprint of paper recycling is more than that of recycling plastic. Until technology can be developed to recycle paper efficiently, it does not seem to be a good candidate for shopping bags. On the other hand, jute and cotton clothes seem to be a better alternative. However, jute bags in the local market are highly priced which may act as a barrier to popularity. Bags made of cotton cloth are also uncommon because of the high price of cotton-made products. These bags are not very user friendly because they take too much space and are difficult to wash after shopping for daily necessities. Until a different form of processed jute can be developed for shopping convenience, it would take time to popularize these bags based merely on environmental concerns to customers.

Option 4:

The fourth option, as already practiced by many countries, is a complete ban on plastic shopping bags or partial ban on a conditional basis. For example, it is illegal in South Africa to use plastic shopping bags that are thinner than 30 micron (1 micron is equal to one thousandth of a millimeter). Shopkeepers found with bags thinner than this would be heavily fined and can be jailed for up to 10 years. Similar conditional ban is imposed in Botswana where it is illegal to use bags thinner than 60 micron. The purpose of requiring the use of thicker bags is to make shoppers reuse these bags and not getting a bag every time they buy something. Thicker bags are also profitable to recycle.

Many countries have already banned plastic bags either in select cities or nationwide. As an example of a nationwide ban, Bangladesh is the first country in the world that imposed a complete ban on plastic shopping bags in 2002. Though other select cities in many countries adopted city-wise ban, a nationwide ban is extremely rare. The second country that adopted nationwide ban was Rwanda (in 2007), followed by Italy (in 2011). Mexico City in Mexico, Modbury in England, Toronto in Canada, some West Coast cities in the United States, Rangoon in Myanmar, and a few select cities in India statutorily banned the use of plastic shopping bags. UAE, Pakistan, and some African countries are also planning on complete elimination of plastic bags through various measures.

The nationwide ban of plastic shopping bags in Bangladesh emanates from analyzing the root causes of floods in 1988 and 1998. Clogging of the drainage system aggravated the flood situation beyond imagination. As a stern measure, the government adopted nationwide complete ban in 2002. The decision was highly publicized in the global media, stirring politicians across the world to think on what to do for managing the same problem in their countries.

Initially, the ban worked well for the country. However, critics argued that the plastic ban caused a huge number of people to lose jobs who were employed in the plastic industry. Consumers were shocked not having alternative shopping bag in place. As a developing country, we cannot afford an outright ban, they claimed. Rather than banning plastic shopping bags, the government could have encouraged gradual adoption of biodegradable bags over time.

No matter how many options the government might have weighed, the outright ban seems difficult to implement at the field level. Since plastic shopping bags offer huge convenience and are popular, it is difficult to eliminate them from the shopping arena. Many retailers are very careful and discreet in using plastic shopping bags, thereby making the implementation of the ban questionable. Many road-side stores selling fruits, vegetable, and fish prefer to use plastic bags because of the nature of the product they sell. Although government agencies frequently visit and fine indiscreet retailers, controlling all the retailers spread across the country is a logistic nightmare. Some argue that strict enforcement and exemplary punishment should be the key. Others argue that a complete ban is not practical. We should rather agree that plastic shopping bags are being used despite ban. So why should we not just think about other options that are feasible at this point other than complete ban of shopping bags?

1. What is the main issue of the case?

2. Do you support complete ban of plastic shopping bags? Defend your answer considering all the options based on the case study.

3. If biodegradable bags are allowed in your country, which type of biodegradable bag would you recommend to use? Defend your position with reasoning, clarifying any assumption you may have.

The case focuses on the environmental and social consequences of packaging issues, particularly sustainability issues of packaging decisions. Although the plot of the case centers on the ban of plastic shopping bags in Bangladesh, it covers the importance of the topic in a global context. The questions at the end of case can be addressed as below.

The main issue centers on the question of complete ban of plastic shopping bags in Bangladesh under the existing socioeconomic scenario. Examples are drawn from other countries on how they fought the problem vis-à-vis the available alternatives at large.

This question can be addressed from various perspectives, depending on the assumptions at hand. For example, a complete ban may be favored because it caused severe environmental problems over time — like clogged drainage system and unprecedented flooding of metropolitan areas. Complete ban will also force customers to choose cloth bags or similar eco-friendly shopping bags despite its cost and inconvenience. Social and economic concern like people losing jobs in the plastic bag manufacturing sector can be handled by policy measures by the government through retraining and shifting the workers to the new type of eco-friendly bag industry.

In another view, complete ban may not be favored because of huge logistic limitations of the government will lead to circumvention of the law by retailers, thereby making the law ineffective in many areas of the country where vigilance is limited. It may also be difficult for consumers and retailers to agree upon a common alternative that would be accepted to all quarters. Social issues stemming from unemployment of plastic bag manufacturing workers should also be of great concern. Therefore, other available alternatives as already mentioned in the case should be carefully weighed before making a decision.

The question poses the reader to make a choice of the type of biodegradable bags considering the case of my country. Two perspectives can be taken into account to answer this question, based on the information given in the case. First, the reader may consider plastic-based biodegradable bags where two types of biodegradable materials are discussed in the case: biodegradable materials mixed in the batch of regular melted plastics or completely biodegradable plastic made from plant origin. Readers may be directed to the relevant information as given in the case. The second perspective is of using nonplastic-based biodegradable materials like cotton or jute. The advantages and disadvantages of possible options available under the two perspectives are discussed. Based on cost-benefit assumptions of the reader, different answers are possible while choosing an appropriate type of biodegradable material; however, readers are expected to present a critical analysis of why their chosen option is better than the other alternatives presented in the case study.