Uditha Liyanage†

This chapter attempts to clarify the key steps of branding, and in the process, lay bare the anatomy of a brand. The existence of a brand as a consumer response rather than as a set of company-generated stimuli highlights that the brand, in the final analysis, is a mental construct and not a palpable physical reality. The chapter delineates the journey from the identification of the brand’s essence to its delivery, and then the creation of impressions of the brand in the consumer’s mind. Hence, the marketer has to understand the consumer’s intra-personal factors; chief among them is consumer perception. In sum, a brand’s anatomy is rooted in consumer behavior as described in this chapter.

The many definitions of a brand that have evolved over time have one basic and essential element in common: it has always meant, in its passive form, the object by which an impression is formed, and in the active form, the process of forming this impression in the mind of the consumer.

The centrality of consumer impressions in the definition of a brand points to its locus. Clearly, a brand exists in the minds of its perceivers. A brand is not a physical reality, but a mental construct. The impressions one forms on a brand must necessarily be different to those on another brand. In sum, consumer impressions of a brand must be distinctive and differentiated from the rest of the brands in its category. This differentiation helps the consumer to readily recognize a brand and in the process, simplify his decision-making process. A brand that has proven to be satisfying and is recognized and recalled at will prompts the consumer to reach for it, multiple times.

The “differential” quality of a brand in terms of consumer impressions also helps the brand owner to set his brand apart from a plethora of brands in a particular product category. The competitiveness of the brand lies principally in its ability to differentiate itself in a way that is desirable to the consumer. In fact, in an increasingly competitive and complex market place, many consider that, in the twenty-first century, branding ultimately will be the only unique differentiator among companies. Brand equity is now a key asset, which, in fact, features in the balance sheets of many companies.

Brands, therefore, exist in the minds of consumers and create value for them by helping them to make purchase decisions, and also in their very use and adoption.

Brands also create wealth for companies who own them, by creating customer preferences, and hence, shaping revenue streams. Today some brands are even more powerful than nations! It is estimated that brand value could be as much as one-third of the entire value of global wealth. The intangible assets of the top 100 global brands, together, are worth well over a trillion dollars. To place this number in context, it is equal to the combined gross national income of all the 63 countries defined by The World Bank as “low income,” and where over half the world’s population lives.

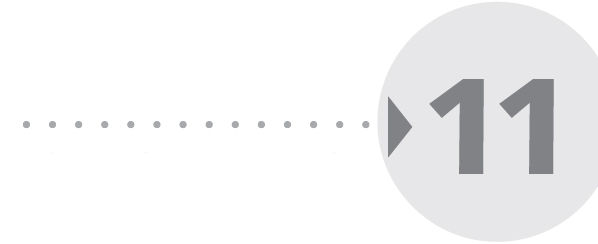

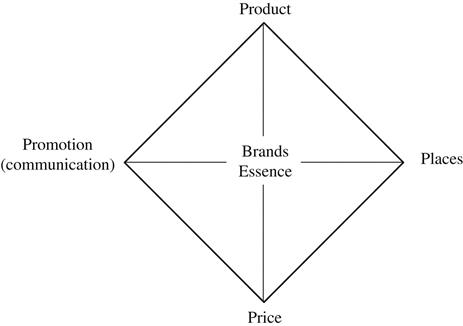

At the heart of a brand is its scope and role, and its value cluster minus price (value proposition) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Brand Essence.

Scope and Role: The question of scope and role is; “where am I?” or the playfield/operating space of the brand and what is its central role in the carefully chosen operating space. For instance, what is the playing field of Singer Sri Lanka? Are they a manufacturer and marketer of consumer appliances, as they were or are they, as they now claim, a retailer of consumer appliances? Who is Sri Lanka Apparel? Are they mere providers of garments, putting the pieces together, or are they proprietors (owners) of apparel brands? They are, as they claim, a partner to leading retailers.

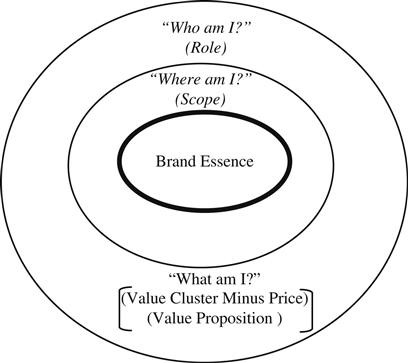

The essential scope and role of the brand is determined by two simple questions (i.e., brand positioning) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Brand’s Scope and Role.

The brand’s stand/position on the market will spell its market or operating space or its domain, the veritable battlefield of the brand. Who was Red Bull when it first entered the market? It was a beverage, and in fact, a carbonated beverage. That is, Red Bull’s stand on the market (i.e., scope). Now, the stand in the market will determine how the brand will set itself apart from other carbonated beverages. Red Bulls’ stand in the market is that it is of an “energy drink” in the domain of carbonated beverages. These two questions: Stand on (frame of reference) and in (point of difference) the market/playing field will determine the brand’s scope and role, its raison detre and answer the vital question: “where am I and who am I?”

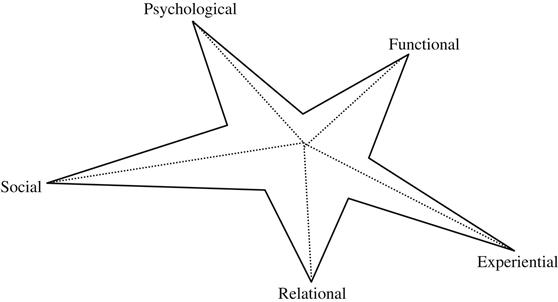

The third question that relates to brand essence is, “what am I”? This is about the brand’s value cluster minus its price or strategic value proposition. The brand must necessarily create value for its customer. It must be “valuable and desirable” to the customer in as much as it is “distinctive and defensible,” in the wake of competition and its total price must relate to the perceived value of the brand’s total offering. A brand is, in fact a cluster of five distinct but integrated values. They can be presented as in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Brand’s Value Cluster. Adapted from Liyanage (2003).1

Each brand has a unique value cluster or a uniquely shaped “value star.” Figure 3 indicates a brand whose experiential and social values are more pronounced than the other three values. There can be multiple value stars, whose configurations should give the company a distinct and sustainable competitive advantage over other brand offerings in the same market space/domain.

Functional value is about, “what the brand does for me?” — the problem-solving nature of the brand. A brand of toothpaste cleans my teeth and prevents their decay. Experiential value is sensory. Here, the brand appeals to one’s senses. It is about “what the brand does to me?” A brand of toothpaste makes me sense/feel fresh and I like the flavor of the toothpaste when I use it to brush my teeth. Relational value is about, “what the brand does with us?” A brand of toothpaste is valued because of its appeal to my peers, to people I like to be associated with and belong to. Social value is about; “what the brand says about me?” Here, the user of the brand becomes a communicator. The very use and adoption of the brand help me to make a statement about myself. It is not the product per se that matters but me the “user as communicator” that does. Psychological value is about, “what the brand says to me?” This is the constant self-dialogue that goes on, the inner chatter that defines “who I am,” to me. This self-concept of the consumer is buttressed by a brand whose values are congruent with the consumer’s value system. The consumer may value a brand of toothpaste made only out of locally sourced material because of the consumer’s intrinsic value for that which is indigenous.

The configuration of these five values vis-à-vis competition brands is the third factor of brand essence (i.e., value cluster). The first two being, as was described earlier, the brand’s scope and role.

How does the brand express its essence? In sum, how does it tangibly answer the triple questions: “where am I?” (scope), “who am I?” (role), and “what am I?” (value proposition).

The expression of the brand’s essence takes four distinct but integrated forms (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Modes of Brand Expression.

The brand’s marketing-mix that is variously described should comprehensively capture the brand’s essence. It must be faithful to its essence and be meaningfully expressed. The product expression is most fundamental. It must contain and indeed physically encapsulate the essential elements of value (i.e., functional and experiential) and also provide a basis for the expression of other values (relational, social, and psychological values). The former is a direct expression of the product and the latter is a proxy for its expression. Toothpaste’s functional and experiential values delineated earlier are direct “value for me.” They are directly related to product-functionality. The other three value types (relational, social, and psychological) are derived from the product (“value of me”). They, in fact, find expression principally through promotion or marketing communications, such as advertising sales promotion, public relations, and personal selling. Moreover, it must be noted that placing the product is not just a matter of consumer convenience, it is also a way of expressing the brand’s scope and role and value proposition (i.e., brand essence). The same is true for the brand’s price. The relationship between cost and price is often direct and linear. This need not be because price is a way of expressing the brand’s unique stand or position in the market.

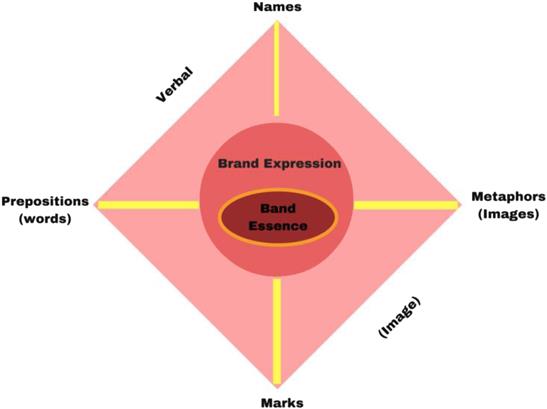

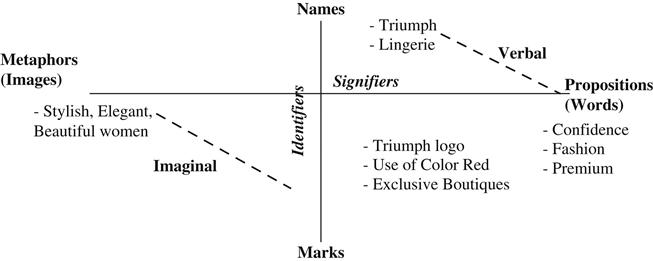

Figure 51 shows the modes of brand impression where (a) names and marks are brand identifiers and (b) propositions and metaphors are brand signifiers.

Figure 5: Modes of Brand Impression.

The brand’s essence is expressed through the elements of the marketing-mix (the four P’s). They, together, relate to what the company “gives” the customer. Now, the customer who is exposed to the brand’s expressions, forms specific impressions of it. They relate to what the customer “gets.” What are the modes of brand impression?

Names help identify brands through their vocalization. The name of the brand, its associated descriptor(s) and the name of the source, the manufacturer or the marketer’s names and marks are also valuable brand properties that are often protected. Marks are those elements that can be sensed about the brand but cannot be vocalized as in the case of names. The unique type face of the name(s) of the brand, the distinctive logos, colors, smells, and the tastes and the “touch and feel” of the brand, its associated sounds (jingles and other sound tracks) are all potentially distinctive marks of the brand which are again very often legally protected as the brand’s unique trademarks. Both names and marks help identify a brand. They are the brand’s unique set of identifiers.

The identification of the brand is one. Its signification is another. Propositions (brand-specific statements as consumer impressions) and metaphors (brand-specific imagery as consumer impressions), together, form the brand’s set of signifiers. They uniquely signify the brand. “Lux, the beauty soap” is a brand proposition and “Lux, the soap of film stars” is a brand metaphor. Importantly, names and propositions are verbal impressions, while marks and metaphors are imaginal impressions. The first are typically left-brain impressions and the latter, right-brain impressions. A brand’s impressions have to incorporate both, and be veritable “whole brain” brands!

The brand’s expressions via the marketing-mix and the resultant brand’s consumer impressions via the verbal and imaginal facets now make the brand come alive; as one which exists in the mind of consumer. The names and propositions (verbal) and marks and metaphors (imaginal), together, form the brand’s mental schema. This is the network of words and images that readily springs to one’s mind when one is exposed to the brand or is reminded of it. Examples of brand impression as mental schema,2 for Volkswagen Beetle, include fun to drive, neat color, easy to park, good winter car, good traction, good gas mileage, German car, and so on.

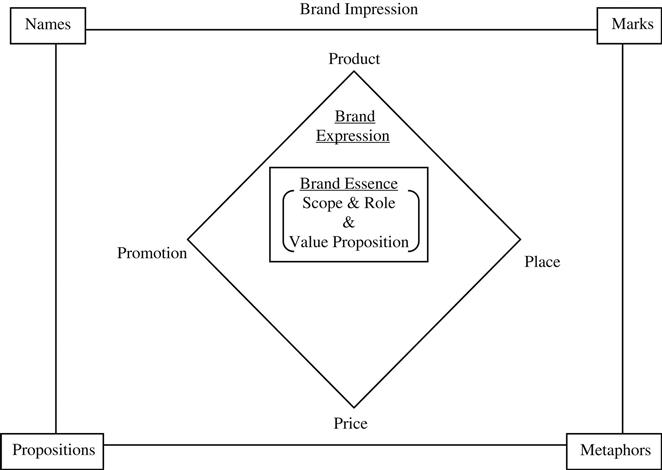

The key point in all of this is that the marketer who is carefully managing the branding process, must ensure the strategic fit between Brand Essence and Brand Expression, on the one hand and the strategic fit between Brand Expression and the desired Brand Impression, on the other. Nothing can and should be left to chance.

From brand essence to brand expression and then to brand impression is a sequential process that must be carefully designed and crafted. We can now discern the anatomy of a brand in its entirety (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Brand Anatomy.

A brand ought to be valued by its customers, without which the brand has no existence. The purpose of the brand or its scope and role to begin with, and the brand’s unique value proposition (value cluster minus price), relate to the essence of the brand. This brand essence must be faithfully expressed using four specific value carriers — the product, promotion (communication), place, and price. The expressed brand’s scope and role and value proposition are now impressed, indeed imprinted in the mind of the consumer in the form of brand names, marks, words, and images. This verbal — imaginal schema is the only real brand construct that exists in the consumer’s psyche and nowhere else.

CASE 1: CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND BRANDING

Branding a Commodity: The Case of Triumph in Sri Lanka

Thushara Wickramasinghe

Uditha Liyanage

Consumers have come a long way from being an economic human being, making rational decisions. They have become progressively sophisticated, and their needs have grown to be increasingly diverse and difficult to decipher. To complicate things further, these needs change at regular intervals. Hence, in today’s dynamic market place, it is becoming increasingly important to identify and continuously meet the needs of the consumers and consistently be in touch with the values sought by them.

The success of a business organization lies in the extent to which it meets the needs of the target consumers. However superior your product is in terms of quality as compared to that of your competitors, however attractive your price points or advertising campaign, they will fall short of capturing a place in the consumer’s mental filing system, or the mental schema, and also will not make a big impact on the bottom line if you are not delivering value sought by the consumer.

The key to being included in the consumer’s mental filing system would be to meet the value consumers seek. The value delivered ought to distinguish the brand (the value carrier) from the rest of the players in the market. In a market comprised products or commodities, establishing and communicating, the values that are attached to a brand will push the brand to desired heights.

A category is defined as “The process of understanding what something is, by relating it to prior knowledge”.

Categorization could be performed in two ways:

• Taxonomic: An orderly classification of objects, with similar objects in the same category (e.g., The category of electric shavers).

• Goal derived: Assignment of things to a category because they serve the same goals, even though they may have very different features (e.g., Electric shavers and shaving cream).

There are associations inherent in each of the categories. The objects that fall into the categories are perceived to possess these associations and are comprehended with the help of these associations. These associations are termed schema. Schema plays a major role in marketing an object to appeal to consumers. As long as the consumer can identify an object as belonging to a particular category, and not be lost in identifying it, marketers may opt to introduce new associations for that object to make it more attractive to the consumer. Subcategories may exist, sharing associations of the main category, and having associations of their own.

Liyanage3 describes a category or a set as a commodity. This category or set will include all the products that are perceived to be of that commodity type. It can have subcategories based on form or purpose. These inherit the associations of the category. A brand is an entity, a referent or a point in that defined category.

In Figure 7, soap is a category, toilet soap is a subcategory, and “Lux” a brand under the subcategory toilet soap. In the formation of categories, intra-category homogeneity and inter-category heterogeneity are normative. A brand possesses some characteristics of its immediate subcategory and, to a lesser degree, those of its larger category.3 The brand-specific characteristics may dominate the identity of the brand or the category-specific characteristics may dominate. In the latter case, the brand may not be that distinguishable from the commodity, whereas in the former, it has distinctive characteristics that help identify it as unique.

Figure 7: Commodity — Brand Linkage. Source: Liyanage.3

The American Marketing Association (AMA) defines a brand as a “name, term, sign, symbol, or design, or a combination of them, intended to identify the goods and services of one seller or a group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors.” These different components of a brand that identify and differentiate it can be called brand elements. Consumers associate the product with the brand through these brand elements; this is a psychological response. If they are removed from a product, only the physiological response to the product remains. In a holistic sense, Liyanage defines a brand as “a market entity whose identity and personality are tangible in the mind of the consumer.”3

Branding is a fundamental concept within the marketing discipline. It has become so vital that hardly anything goes unbranded, not even fruits and vegetables. Consumers view a brand as an important part of a product, and branding can add value to a product.4

Branding is a two-way street as it helps consumers make a purchase decision and stick with it each time they purchase the same goods, rather than make the decision by considering a series of facts each time they visit the store. The brand assures that they will get the same features, benefits, and quality each time they buy the product. It also helps the supplier as it assists them in communicating the values attached to the product to the consumers more clearly.

The concept of customer value is central to the design and development of brands.1 The customers also get differentiated value out of a certain brand through various attributes associated with the brand. In sum, a brand is a promise; it is a value offering to the customer.

Sheth, Newman, and Groos5 refer to functional and emotional value as two of the five values that influence consumer choice behavior. The marketing literature refers to this concept in different ways. Functional dimension relates to what the product or service does. The emotional dimension relates to the feelings held about a brand. This is the dimension that is concerned with feelings, sentiments, moods and emotions about the brand. Aaker6 brings a third dimension into the equation, a value proposition based on self-expressive function. Here, functional value refers to the “Use Value” and the non-functional value refers to the “Sign Value.”

Some refer to these two dimensions as stemming from the two hemispheres of the brain. That is, think products that are usually processed logically and analytically, implying rational sequential thinking; hence, left brain processing. Feel products that usually use a synthetic, holistic, and intuitive approach are characteristic of right brain processing.

It is further perceived that intrinsic product attributes (attributes that are tangible and intrinsic to the brand, and those that produce its performance) lead to functional value which have a relatively weak emotional response, whereas extrinsic brand attributes (attributes that connote meaning or are derived from associations of the brand) lead to non-functional value, which have a typically strong emotional response. From this distinction, it is clear that it is not the brand attributes that lead to functional or emotional value, but it is rather a perceived value, which may motivate a consumer to act.

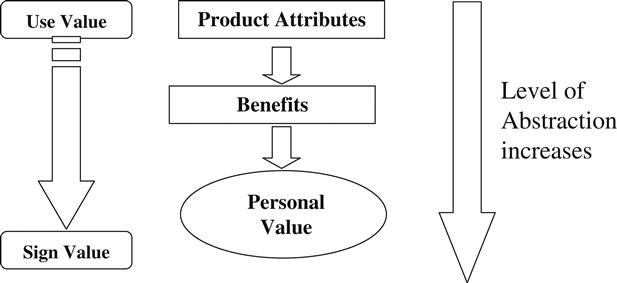

Gutmen7 and Reynolds and Gutmen8 provide a more comprehensive explanation of the concept of “value” through the means-end chain. Here, personal values are the ends people seek and means are the things people use to reach those ends. Means refer to the product attributes and benefits or consequences that flow from those attributes. Personal values are described as motivating end-states of existence that individuals strive for in their lives.9 As one moves up the ladder of the means-end chain from attributes to end values, the level of abstraction increases, and the value sought changes from instrumental to terminal. These two levels of abstraction are referred to as “Use Value” for the functional value and “Sign Value” for the non-functional value. Use Value is further classified as “value for me” and Sign value as “value of me”. These are the two broad value paradigms (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Means — End Chain and Progression of Value. Source: Adapted from Liyanage (2003).

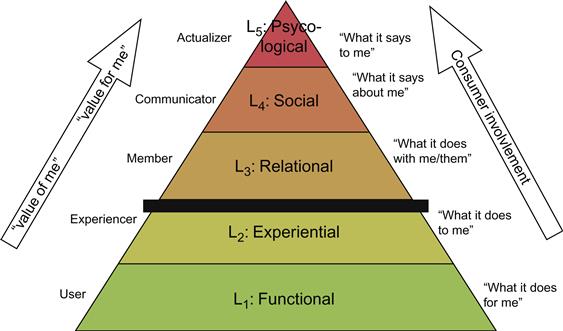

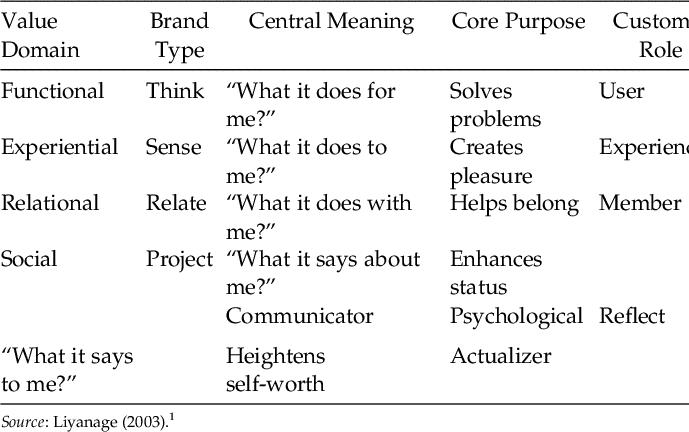

By expanding the above, Liyanage1 defines five-value domains with a hierarchical ordering. In this classification, brand types, central meanings, core purposes, and roles are assigned to the consumer for each value domain. This has relevance to the means-end chain, as the five values could be placed in the chain with an increasing level of involvement on the part of the consumer.

It is argued that brands acquire deeper meaning and associations as one moves up the value pyramid from “value for me” to “value of me” (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Liyanage Value Pyramid.1

Table 1 indicates the five value types and how they relate to the consumer’s role and purpose for each type.

Table 1: A Brand Value Typology.

Triumph International started in 1886 as a family company in Heubach (Württemberg), Germany, and 115 years later the company is represented in almost every country in the world. The company produces and markets “Intimate Apparels” — lingerie and nightwear, swimwear and beachwear as well as men’s underwear, swimwear and home wear.

Triumph set up operations in Sri Lanka in 1995 under the name of Triumph International Lanka (Pvt.) Ltd. — a privately owned, international company. It created a paradigm shift in the way intimate wear was worn, treated, perceived, and marketed in Sri Lanka (SL).10

Triumph’s signature presence is evident through open displays, strong branding and innovative and colorful range of styles. Triumph in SL is known as a company that markets innovative and fashionable intimate wear and is perceived as the “aspiration brand” in the lingerie market. On commencing the second decade of its operations in SL, Triumph continues to delight customers with an array of new styles and more exclusive locations for lingerie shopping with an outstanding ambience and service.

Triumph enjoys a 15% penetration in the urban market. Lingerie marketing is still in its infancy and the market comprises a significant percentage of young adults. In the fashion segment, value growth generally outstrips volume increases. Triumph enjoys an estimated 27% value share in SL.10 The level of performance achieved by Triumph in a relatively short period of time indicates the market response to a sophisticated brand. The segment of the market comprising consumers of a higher socio-economic group appears to have been the initial respondents to Triumph’s value proposition.

The vision of the company is “To be the fashion brand that every Sri Lankan woman aspires to experience,” the brand positioning being “An ‘innovative fashion brand’ that offers ‘ultimate wearing pleasure’ for ‘contemporary women’.”

Triumph in SL adopts a multi-channel distribution strategy in order to effectively reach a wider group of customers. The three main shopping malls in Colombo-Crescat Boulevard, Majestic City, and Liberty Plaza have exclusive lingerie boutiques and there are counters in all key locations such as Odel, Nolimit, Beverly Street, Fashion Bug, and fashion retailers island-wide. These outlets serve as direct sales points. There is a dedicated sales counter at the head offices to serve the dealers from the network-marketing channel, the retailers and any customers who walk in for purchases.

The transformation of Triumph International into one of the world’s leading manufacturers of lingerie and underwear is a global success story. The owner-operated company with 48 subsidiary companies now enjoys a presence in over 120 countries. For its brands Triumph, Sloggi, Valisere, and HOM, the company develops, produces, and markets underwear, sleepwear, and swimwear both wholesale and through its own retail establishments.

In Sri Lanka, Triumph International Lanka (Pvt.) Ltd. mainly focuses on the lingerie (underwear) market. At the time of the Triumph launch, the market was underdeveloped and very narrow. It was a commodity market and associations that existed with the subcategory “underwear” as it was known back then and within the larger category “clothing.” The main attribute of the category was to “provide support.” A main aspect of lingerie — “fit” — was measured in a one-dimensional space, where only the band size was taken into consideration. “Fashion” was unheard of.

When Triumph did its launch, the first uphill task it had to perform was to define the market. Earlier, the bra was known as an item of clothing that was “ugly,” and worn just to serve a functional need, less comfortable, and literally thrown to or hidden in a corner of the wardrobe. There was just one style available that had penetrated the entire market, suitable only for the saree jacket. They were available only in a restricted color range, black and white. Sizing was based on band size, and was available only up to size 34.

Triumph had to transform the unglamorous “underwear” category into a much more glamorous “lingerie” category. To do so, they opted for the method of communicating the different attributes or associations that exist for lingerie. In other words, Triumph made its broad consumer base, 16–60 years, middle and upper income earning females, aware of the different associations that exist with the word lingerie, and what was lacking with the products in the Sri Lankan market. Hence, the first brand values were launched: Comfort, Fashion, Quality, and Innovation. These initial brand values are, in essence, intrinsic product attributes which defined the category “taxonomically.”

Moreover, these attributes defined not only the category but also the foremost player in that category, the brand “Triumph.” The first set of brand values launched by Triumph concentrate more on the “Use Value” component of consumer value, of “value for me.” As the knowledge of the consumers grew with time, they would realize the importance of the “sign value” or “value of me” to the consumer. The value proposition could then be changed accordingly.

By changing the values associated with the word “lingerie” (Fashion, Innovation, Quality, Comfort), Triumph redefined the benefit women derived from wearing lingerie.

The company strived to transform these values into providing the consumers with an end benefit that is to be “Fashionably Confident.” Therefore, functional value was just the means to an end, the end being to make women feel “Fashionably Confident.”

Changes to the attributes consumers identified with, when it came to lingerie and extensions to the associations of the word “lingerie,” were not done overnight. This uphill task was achieved as a result of a series of brand communication strategies that were aimed at transforming old-fashioned, functional lingerie into a piece of clothing that had an emotional impact on the women who wear them.

Initially, the company did not target a specific target segment, but tried to pitch into all the different segments that existed within the broad consumer base. However, it soon realized that this approach makes their differentiation strategy weak and proceeded to identify the different types of consumers, so that it could aim at the selected segments based on consumer need, and not on price points. As such, three primary segments were identified.

• Culture Custodians: More conservative, traditional women.

• Wannabes: People who want to be fashionable and look smart, but do not have the disposable income to spend on being so. This segment has potential for future sales.

• Career Warriors: This segment is the main market, they are career-oriented women who thrive on being fashionable and who have significant disposable income to spend on being so.

Out of these three segments, the target groups were reduced to “Wannabes” and “Career Warriors.” The basic profile of these two segments was 18–35 years, strong, independent, empowered women with a defined sense of fashion.

In the traditional lingerie market that prevailed, a bra could only be distinguished by band size, and had a minimal color range of two (black and white). However, Triumph came and redefined what was known as “fit” in a bra; that there are two dimensions to it rather than one band size as well as cup size. They introduced bras that had a superior fit.

They invited the women and young girls to come and check out the fit that is ideal for them, and how wearing the bra with the correct fit enhances your outer appearance and posture. In short, they communicated to the market that “There’s a bra for you.” Triumph repositioned the lingerie and bras in particular as a fashion accessory. The channel chosen to distribute the products was ideal for this approach — Exclusive Boutiques. This revolution in the functional dimension is the first peg through which they drove home their competitive advantage of being an international level lingerie producer.

Once the key customer group was identified, Triumph went on to identify the different product categories that are needed when servicing these consumers. The distinct product categories that were identified in this study were:

• Functional: Feeding Bra, Sports Bra, Sanitary Briefs, Girdles

• Specialty: T-Shirt Bra, Maximisers

• Basic First Bra, Form and Beauty

• Fashion: Underwire and non-underwire, Lace Styles

The current products that were in the market clearly did not cater to these distinct product categories required to satisfy the needs that existed in the market. Although they provided the basic need of assisting to maintain form and beauty, they were in no way suitable for the other needs that were present. Triumph had to educate the consumers that there is lingerie designed for different functions or purposes, such as sports and feeding, briefs designed with different functionality, and also specialty bras in the form of t-shirt bras depending on the outerwear, maximizers, minimizers, etc.

They also brought forward the more glamorous “fashion” attribute into lingerie. While women were used to only one style of bras in a limited color range of black and white and basic briefs, Triumph presented an exciting range of vibrant colors and different styles of bras and briefs to suit the occasion and need. Their lingerie was adorned with exquisite laces and high-quality fabrics mostly sourced within Europe, underwire Bras were introduced to provide additional support and form alluring figures, party bras were introduced that could be worn with evening wear of different styles. This helped women to expand their horizons of fashion and look attractive and glamorous in whatever the outerwear they wish to be dressed in.

While they introduced the attribute of glamour into the market, they were also careful not to completely ignore the more traditional women who preferred to wear the conventional attire of the saree. For them, Triumph has a classic collection to suit their purpose. This range is mostly locally produced in the MAS apparel factory Bodyline, and is priced relatively lower than the imported range. This range offers the same support and shape that is provided by the most patronized player in this segment “Senorita” while offering the additional benefits of comfort and a better fit, and also an improved color range. The look and feel offered by Triumph in this range is also, by far superior to the other local players, and the quality too is unmatched.

Triumph’s successful entry and acceptance in the market place was based on two key differentiators:

• Innovative Fashion Styles — Innovative designs, vibrant colors;

• Revolutionizing the retail landscape in Sri Lanka in order to provide a complete brand experience using a multi-channel distribution strategy.

When Triumph entered the Sri Lankan market to introduce high-value lingerie to the market, the first channel chosen was its own boutique in Majestic City, a shopping mall patronized by the majority of the urban population in Colombo. Exclusive lingerie boutiques were an innovative and revolutionary concept for Sri Lankan women. In these boutiques, women could be free from prying eyes and be among others from their own gender and check out lingerie that makes you look good. Triumph revolutionized the dormant lingerie market through the use of bold product-marketing strategies that differentiated its products from those of its competitors.

The setting up of the Triumph Boutique enabled the company to continue to test new challenges such as price resilience, style acceptance, and color preferences, before rolling out to broader retail markets. It also helped drive its fashion positioning, through the concurrent introduction of innovative concepts launched regionally at its boutiques.10

Unlike in a retail store that has poor lighting, store layouts, and poor merchandise display when it comes to lingerie, in a boutique, Triumph is in control of the atmosphere. They could make it as pleasant to the consumer as possible to transform the chore of lingerie shopping into an “experience.”

As brand awareness was being created in the market, the company put yet another innovative idea into practice. They launched a direct sales network. Triumph being a premium brand that required a certain level of education, a network-marketing channel was an appropriate means to penetrate the market, and was an excellent channel to reinforce brand benefits to customers. It also offered self-employment opportunities to Sri Lankan women.

While both these delivery channels were in progress, Triumph went into a third channel with the mass market in mind to make their products available through the established retailer network. This was carried out keeping in mind that the majority of the market does not patronize the exclusive lingerie boutique or have access to the direct sales network dealers, but did their clothes shopping with organized retailers.

The company observed an exponential rise in boutiques sales very clearly. This confirms that the company is on the right track. Triumph believes that the most valuable distribution channel for them currently shows most potential for the future, and the one that provides most value to the end consumers is exclusive boutiques.

Brand values play an essential role in building the brand and as a result create brand equity. The initial brand values projected by the company from the launch in Sri Lanka back in 1995 were Comfort, Fashion, Quality, and Innovation. Functional value was given priority. However, the global company soon realized that the continuity of these values over a long period of time led to Triumph being categorized as an old-fashioned brand that is not in tune with the contemporary woman. In fact, the company later realized that the initial brand values were, in essence, the production engineer’s idea of marketing: communicating product attributes. Thus, the first steps of changing the category were based on features of the product.

Hence, while maintaining the superiority the brand had in terms of the old value attributes, Triumph launched a new set of values in 2007 to be associated with the brand that is more in line with the end benefits of the brand. These were slightly changed again in 2009. While the initial set of brand values concentrated on the “Use Value” (e.g.: Comfort, Fit, etc.), the later set was more in tune with the “Sign Value” (e.g.: Confident, Empowering, Sensual, etc.).

Communication of these brand values starts from how Triumph approaches a collection at its inception and is driven down to how the collection is marketed. The new brand communication would demonstrate women who are in control of themselves and their environment.

However, in Sri Lanka, sometimes the changes introduced to brand values are a little ahead of the market. Therefore, the response of the Sri Lankan market to these changes is comparatively less intense than that of Western markets. There is also another crucial factor that affects these brand values from being projected to the Sri Lankan market, that is, the cultural taboos that exist against nudity. Hence, the company has restricted themselves in the use of imagery exclusively within the boutiques and within the retail enclosures where the products are on sale.

In order to communicate the values and attributes of the brand to the market and create awareness, Triumph has carried out various brand communication strategies. As they launched the product in the Sri Lankan market, the biggest billboard for them was the Triumph boutique at Majestic City. This announced their presence very loudly to the shoppers patronizing the shopping mall, who represented a large portion of their target consumer base.

Triumph also used another novel way of communicating the superior value offered by the brand. It adopted a premium pricing strategy that reinforced the brand’s positioning of being an “innovative fashion brand.” This strategy, although acting as a deterrent to some segments of the market, sent a very strong message that here is a brand that is superior to all other generic products available in the market in terms of the traditional yardsticks, and offers much more than any other product in the category.

The brand Triumph by now was a discreet mental schema in the target consumer’s mind. Its four cognitive facets are illustrated in Figure 10.

Figure 10: Schema of the Brand. Source: Compiled by Liyanage (2001).11

At the point of entering the market, Triumph found it very difficult to grasp the needs and wants of the market, as there were no tracking studies available for this particular market, viz. lingerie. As an international lingerie manufacturer and retailer, Triumph realized the need to fill this knowledge gap, and the importance of understanding the consumer. The most important endeavor that stands above the other efforts in understanding the consumer has been the brand equity studies (BES) carried out by Quantum Strategic Services (Pvt.) Ltd., on behalf of Triumph, first in 2003 and next in 2007.

The brand equity study mainly focused on evaluating brand recall and understanding of the brand attributes among the consumers. This study confirmed the fact that Triumph is perceived as a high-value brand without a doubt. However, the brand is restricted to a niche market penetration.

From an Expert image, the brand relationship with Triumph has now grown into a bonding relationship with a Mother. The relationship with the “Mother” is projecting a multi-faceted experience to the user through which the relationship is taking a turn toward becoming My mother = My lifetime friend. The relationship is opening up to an understanding of a two-way dialogue between the two. This is the same characteristic of the brand relationship between Triumph and the consumer.

Another part of this study compared the brand with its competitors in terms of factors that affect brand loyalty. It was revealed that Triumph has a high appeal in terms of “Durability,” “Comfort,” “Body shape,” “Value for money,” “Colors/Designs,” and “Good-fit.” The only factor with low appeal is being “Price.” Although the consumers are convinced of all the factors that build up Triumph as the ideal lingerie, the price may stand in the way of them being loyal to Triumph.

The most important observation is that Triumph users take the overall finish to their hearts, and derive satisfaction from using a superior product. Other users derive satisfaction mainly by purchasing a product that is “value for money.” Triumph has a clear identity of being a “Premium Brand.”

Every company endeavors to create a positive attitude in the consumer’s mind with regard to their brand. The cognitive component of attitudes affects the ultimate purchase decisions; as the majority of our purchase decisions take the think → feel → act route. Therefore, positive attitudes will go a long way in setting the thinking process in motion and making the brand popular among the consumers. Attitudes do not remain static, they evolve over time as a reaction to the environment. Triumph had to take this process of attitude creation one-step further as they had to create and drive forward the attitude that is attached to the category as well.

• Past: Mother to Daughter → Functionality

• Present: My Private Domain → Femininity

• Future: Spice of Life → Sensuality

The attitudinal change indicated above clearly reflects the transformation in value paradigms in the consumer’s mind from “value for me” (Functionality) to much more private and intimate “value of me” (Sensuality). The attitude transformation led by Triumph has predominantly assisted the company to put its stamp very clearly in the Sri Lankan Lingerie market, and establish its name as the number one lingerie brand in the country.

Sri Lanka is a country that is heavily influenced by Eastern culture. Therefore, the subject “lingerie” is still considered as taboo by most parties. Hence, independent reviews performed of the lingerie market or the company in particular without their involvement are very rare. Therefore, the authors decided to employ the best method of capturing the dimensions of consumer value and the sentiments toward the brand “Triumph”; a consumer survey and a field study covering three key stakeholder groups. This permitted the authors to gain firsthand information about the consumer base.

• Consumers

• Boutique sales personnel

• Direct Sales network dealers

The survey was done through a questionnaire with a convenience sample that was exclusively female. One might consider this fact as being a restriction in the survey. However, the authors’ intention was to capture the rationality behind why females who ultimately become the end user, purchase lingerie. From the demographic details, it could be deduced that the average profile of a respondent was females of 25–30 years of age, graduates who hold executive level jobs and earn a monthly income of Rs. 50,000–100,000. This coincides with the key target group of Triumph.

The survey was designed to capture the preference of consumers toward branded lingerie vis-à-vis generic lingerie. Eighty-five percent of the respondents preferred Branded lingerie in contrast to the 15% who preferred generic products. This is a long way forward from a commodity market that only comprised unbranded products. Ninety-seven percent mentioned Triumph as the salient brand, while some coupled it with the local brands; two respondents did not specify a salient brand. Nine respondents (14%) out of the 63 who mentioned a salient brand stated that they do not patronize the brand in the local market, while 54 respondents (86%) stated that they do.

The majority (21% or 39%) of the consumers who purchase the brand do so more often than not, 28% (15) patronize the brand exclusively, while 28% (15) do so occasionally. By observing the results of who introduced the respondent to the brand, it was seen that the “Mother to Daughter” link does not hold any more when it comes to branded lingerie. Only 28% claimed that their mother introduced them to the brand, while the other 72% claimed other sources such as advertising, friend, colleague, and other.

The main reason for not patronizing the brand is the premium price, as was highlighted in the brand equity study. Only a small fraction (1/9) of respondents believed that the brand does not offer anything special in terms of value (quality, fashion, etc.) delivered. Three respondents felt that the value proposition offered by the other products in the market is more attractive.

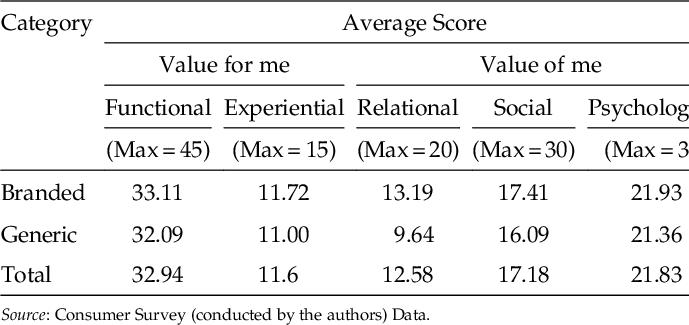

The second component of the analysis on consumer value comprised a set of statements, to which the consumers were requested to state their preference on a Likert scale. The statements included in the questionnaire were an assortment that represented the paradigm “value for me” as well as “value of me.” Eleven statements represented the paradigm “value for me”; whereas 17 statements represented “value of me.” The analysis of the answers given is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Summary of Results on Consumer Value, Value Paradigms.

Category |

Average |

|

Value for Me |

Value of Me |

|

For consumers who purchase branded lingerie |

44.8 |

52.5 |

For consumers who do not purchase branded lingerie |

43.1 |

47.1 |

Total sample |

44.5 |

51.6 |

Source: Consumer Survey (conducted by the authors) Data.

The summary of information indicates that emotional value takes a higher place in the consumer’s minds when purchasing lingerie. This is demonstrated by the average scores for “value for me” being 44.5 as compared to the score of 51.6 in “value of me.” Triumph can claim the credit for most of this attitude of change, since they are responsible for educating the consumers about the different aspects of lingerie, and providing the consumers an idea of a “Total Experience” with lingerie.

The survey results further highlight the fact that the emphasis placed on “value for me” is very similar among the two categories of consumers. However, a clear emphasis could be placed on “value of me.” The score for this is considerably lower for the consumers not purchasing branded lingerie at 47.1. For those who do, the score is as high as 52.5. Therefore, from these results, we could conclude that although “Value for Me” criteria (Functional and Experiential value) need to be met, the consumers who purchase branded lingerie place more emphasis comparatively on the “value of me,” or emotional values such as Relational, Social, and Psychological.

A further analysis of the data to observe the pattern of consumer value in relation to these five value domains (Functional, Experiential, Relational, Social, and Psychological) exhibited very interesting results. This analysis is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Summary of Results on Consumer Value, Value Domains.

It could be observed that for all five-value domains, the values sought are higher for those purchasing branded lingerie. However, for the two domains of “Value for Me,” a distinction cannot be made on the score. This indicates that both these categories are equally conscious about what the lingerie they purchase can do “for” them. However, when analyzing the results for the value domains that belong to the paradigm “Value of Me,” the results are different. A clear difference can be observed for the value domains “Relational” and “Social.” The scores for consumers purchasing branded lingerie are considerably higher for these two value domains. This highlights that they are more concerned about what the product or brand does “with” them, and “what” it ‘says about them. Although it was expected that this pattern would be extended to the “Psychological” value domain, this was not so. From the consumer survey results, it could be observed that both these categories are emotionally attached to their lingerie and derive personal satisfaction from them. Whether “Branded” or “Generic,” lingerie whispers the same message “to” them.

The second segment of the study was carried out by meeting with the sales staff attached to the exclusive boutiques. Since the exclusive boutiques are not visited by a large portion of the consumer base, the intention was to capture the sentiments of the consumers who do patronize the boutiques.

Based on the results, customers spend 10–20 minutes in the store on average. This indicates that the customers are willing to spend some time in comparing different styles and trying out the lingerie for the perfect fit. They visit the store mostly with their friends/partners, indicating that Triumph has managed to break through the barrier where women were embarrassed about lingerie and preferred to do lingerie shopping alone. The boutique staff have reconfirmed that the customers are indeed attracted to the ambience in the stores. The encouraging atmosphere that is created by the layouts, lighting, music, variety offered by the complete range, and the specialized staff, all contribute to drive sales in the exclusive boutiques.

They are also enthusiastic about the in-store promotions that are done from time to time in the boutiques, and there is an increase in footfall when these promotions are carried out. They are also willing to be included in e-mail mailing lists so that they could be up-to-date with the latest news from Triumph. Consumer loyalty is also indicated by the repeated sales being in the 25–50% range. This represents the exclusive consumer base that is 100% loyal to Triumph.

The next section of the field study was dedicated to capture the value sought by consumers when purchasing Triumph lingerie through the direct sales dealer network. The dealers do not have samples of all the styles in possession.

From the results, it was observed that majority of the sales are driven by using the catalogues. It can also be seen that a larger portion of the enquiries are converted to sales. This pattern is a result of most of these dealers having a loyal clientele. This result is fortified by the repeated purchases being considerably higher in the exclusive boutiques.

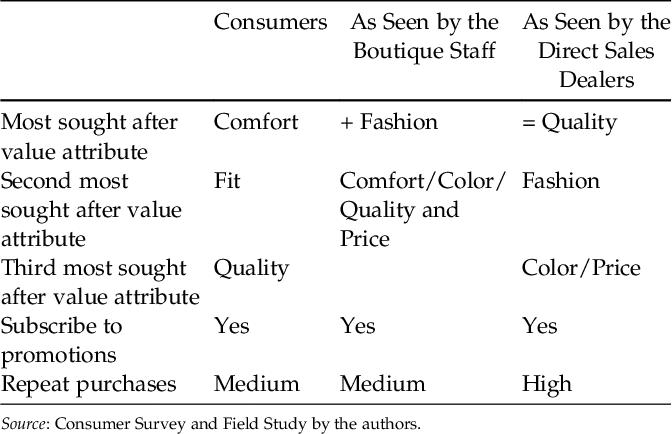

The consumer survey and the field study enabled the authors to gain firsthand experience of the consumer sentiments toward lingerie in general and Triumph in particular in the Sri Lankan market. If the results of the consumer survey and the field study are to be summarized, they would stand as in Table 4.

Table 4: Summary of Results of Consumer Survey and Field Study.

It is interesting to observe the difference in key value attributes sought by the consumers in general and as seen by the boutique staff and direct sales dealers. The most noted absentee in the three most important value attributes for consumers is “Fashion.” It could be assumed that this is a result of the sample comprising women who are not partial to branded lingerie and the additional value they offer together with the women who do place a great emphasis on these additional values. Quality features in all three sources as an important value attribute. The quality assurance delivered by Triumph could be one of the main reasons women purchase the brand while cheaper products are available with a much lower price tag.

Boutique staff as well as the dealers has identified the importance placed by the customer on “Price.” This is somewhat worrying for a brand that offers superior value for a premium price. Since Triumph adopts a “cost plus” mark up to determine price, they cannot afford to price the product at a low price range. The company will have to work hard in retaining the existing consumers and gaining new customers due to this fact.

From the Triumph case study, it may be observed that Triumph has now established its brand soundly in the Sri Lankan market. In the process, it has managed to transform the dormant “Underwear” market into a much more glamorous “Lingerie” market; and hence change the commodity market into a branded market.

Being the largest player in the lingerie market in the world, Triumph has extensive procedures in place to capture the value sought by the consumers. As a result, the values projected change from time to time to reflect the growing sophistication of contemporary women. While the initial values were concentrated on the functional value, the latter values reflect the Emotional relationship women have with their lingerie and are aligned with the confident woman who believes that she can conquer the world.

The main strategy adopted by Triumph in order to achieve this is to communicate the superior value attributes that are a part of the brand “Triumph.” This increased customer knowledge not only helped Triumph to establish itself in the market, but also forced the other players to expand their value attributes in order to retain the market share. However, it can be clearly seen that Triumph leads from the front by being innovative and offering superior customer value. By using various means, Triumph has carved a niche for itself in the lingerie market of Sri Lanka.

In Sri Lanka however, there are barriers to applying the values driven down by the mother company, as there are cultural taboos as well as a lower level of sophistication of the female clientele compared to the European market. The Sri Lankan consumer base still places emphasis on the functional and experiential values of lingerie. However, the growing number of brand conscious females signals potential for Triumph as consumers are also becoming aware of the emotional attributes or values of the lingerie they purchase.

Branding certainly has brought success to a multitude of organizations in Sri Lanka. The act of convincing the Sri Lankan consumer to purchase a brand rather than a commodity is the cornerstone of the success of Triumph in Sri Lanka.

1. How would you distinguish a brand from a commodity? What are the lessons you can learn from the case study?

2. Can an organization build a strong brand on weak functional value of the product?

3. How important is innovation in building strong brands?

4. What is a brand schema? Take on example of a brand of your choice in answering your question.

Answer guide Q1:

The first question addresses the fundamentals of branding. A commodity is generic. It is a category. A brand, on the other hand, is an entity within that category. A brand typically moves up the value pyramid from functional to representational value, while commodities tend to remain at the bottom of the pyramid-functional value.

Answer guide Q2:

This question will help students to avoid the mistake of believing that branding is all about “smoke and mirrors.” If Triumph did not have a strong product with functional excellence, it would have failed to develop a robust brand. Brands must be placed on a strong functional foundation.

Answer guide Q3:

This question relates to value innovation. The challenge before the brand manager is to clearly differentiate his/her brand from others. This differentiation can come either from “value for me” and/or from “value of me” domains. The way to differentiate, therefore, is value innovation. The point is to create a “new and different value” rather than give “more of the same value.”

Answer guide Q4:

The case study refers to the important concept of brand schema. It is the total mental construct of the brand. The words, images, along with names and marks of the brand are the chief constituents of the brand. The example taken by the students should exemplify and illustrate these four dimensions of brand schema.

CASE 2: CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND BRANDING

Garuda Indonesia: Building the Brand

Hermawan Kartajaya

Jacob Silas Mussry

Iwan Setiawan

Syed Saad Andaleeb

The Indonesian airline market with more than 100 million customer traffic per year is one of largest markets in the Asia Region. There are three major groups of customers: middle-up market (20–30%), medium market (10–20%), and low-cost market (50–70%).

Studies on the Indonesia market show that lifestyle is one of the characteristic of middle-up market; they buy products and services based on lifestyle trends. They also not only try to fulfill basic needs but most of them use the product and service as part of their lifestyle to improve their image in society.

The trend of new technology, fashion, entertainment, the way of life, and anything new will be adopted by the consumer. For example, Indonesian consumers’ purchase of mobile phones is not based on function but more on acquiring the latest model and pricing. The more expensive the product, the greater the brand image of that product. Using new technology and becoming the first user will be perceived as being modern, something people like to do to update their lifestyles.

Garuda Indonesia is the largest airline in Indonesia. It was established in 1949 as the country’s flag carrier. It is one of the members of the Sky Team with headquarters in Jakarta, Indonesia. Garuda Indonesia operates in several markets: the Asia Region, domestic Indonesia, Europe, Middle East, and South West Pacific with more than 190 aircrafts representing a modern young fleet that includes Boeing, Airbus, CRK, and ATR with average age of less than five years. Garuda flies to more than 70 destinations with more than 500 flights per day and is a global player in the airline industry, especially in the Asia Region. Focusing on the middle market as a full service airline, Garuda Indonesia targets the middle-up market. As a public company, its commitment to shareholders and all other stakeholder reflect the spirit of the organization.

Garuda Indonesia has more than 24 million passengers per year, domestic and international combined, from the middle-up segment with high expectation on all aspects of service. Recognized as the premium brand, Garuda Indonesia recently became a 5-STAR airline and is one of the Top 10 Best Airlines in the world; it is especially recognized as having the best cabin staff in the world.

Before 2005, with a long story of business and operational services as one largest airline in the domestic market, Garuda Indonesia was facing a really bad situation with many problem in its business, organizational, financial, and operational/service aspects. The negative profit, as a result of the whole organization’s activities, brought the company a bad image and perception. The company was unable to produce enough profit to develop the business and offer good products and services to fulfill consumer needs and wants. The situation impacted Garuda Indonesia’s competitiveness in the market and failed to get more passengers and sell more products and services in the premium price category. The company’s ability in terms of production was also really poor with a bad reputation on On-Time Performance, making the situation more complex. The organizational situation before 2005 is shown below:

Garuda Indonesia Multidimensional Problem before 2005 |

||

Organization and management |

Finance |

Operational services |

|

• Not market-oriented organization structure • No correlation between organization structure, business process, and KPI • Low productivity • Low trust |

• Organizational loss • Negative cash flow • Huge debt • Diluted equity • Debt-to-equity ratio |

• Low on-time performance • Decreasing yield • Sub-standard product and service quality • Too many aircraft type and aging • Low aircraft utilization • Low customer satisfaction |

Source: Garuda International (Author compiled different data from annual reports from Garuda International).

With poor performance and multidimensional problems mentioned above, Garuda Indonesia was facing a “really bad” situation in the market. Using old aircraft with average age of more than 12 years and its old premises and style really could not fulfill customer needs and wants; they could find better products and services easily from the other airlines in the neighborhood like Singapore Airline, Cathay Pacific, and other Asian carriers.

The reputation of Garuda Indonesia brand was very poor at that time and far from the top 100 airlines in the world with low-level quality products and services in the industry.

Based on Garuda Indonesia’s internal survey in the middle-up market, it was found that Indonesian consumers choose their airline based on several criteria with reputation as the main reason. Reputation means it has good positioning in the market, offers more premium products and good services, and most of people recognize them as part of their lifestyle.

Considering the market and consumer behavior, Garuda Indonesia transformed the business, organization, and financial and operational services to became the new Garuda Indonesia to reach the promising target markets with premium products and premium price. In 2005, Garuda Indonesia developed a strategic plan called as “Quantum Leap” from 2006 to 2011 and beyond. The plan focused on three phases: Survival (2006–2007), Turnaround (2008–2009), and Growth (2010 + ). The year wise plans were

Quantum Leap |

||

Survival |

2006 Consolidation |

– Cost efficiency/revenue improvement – Reduce negative cash flow – Capital injection approved by government |

2007 Rehabilitation |

– Ongoing debt restructuring – Product and service enhancement – Cost efficiency/revenue improvement – Positive cash flow/strengthen capital base – Introducing voluntary retirement scheme |

|

Turnaround |

2008 |

– Start of privatization process – Improvement of product and services |

2009 |

– Competitiveness and expansion to domestic/regional – Launched Garuda experience |

|

Growth |

2010 |

– IPO Quantum Leap (increasing revenue and margins driven by rejuvenating main brand fleet and growth of Citilink) – Sustainable growth |

2011 |

||

Source: Garuda International (Author compiled different data from annual reports from Garuda International).

After five years of implementation of the Quantum Leap Program starting with a very basic program for survival, especially in the product and services program enhancement, Garuda Indonesia made big changes in its entirety based on the consumer needs and expectations.

Offering new and latest model aircrafts, supported with information technology and Indonesian hospitality were the main drivers of the strategy. The company also uplifted the cabin crew’s attitude and behavior, improved the ground crew and facilities, brought improvement in product and service reliability, and strengthened security and safety record and on-time performance.

Based on the program above, gradually consumer trust in Garuda Indonesia began to grow and they started to use the airline. Brand recognition of Garuda Indonesia was reinforced in domestic and international markets. Financial performance also improved significantly compared to one decade earlier and Garuda produced profits for the development of the company and enhance shareholder value.

Performance picked up because consumers came back to choose Garuda Indonesia as their preferred Airlines in Indonesia. Increasing the number of passenger traffic, new destinations, increasing of number of aircrafts, projecting a premium brand image, and pricing as a full service airline brought Garuda Indonesia into a new horizon as a premium brand.

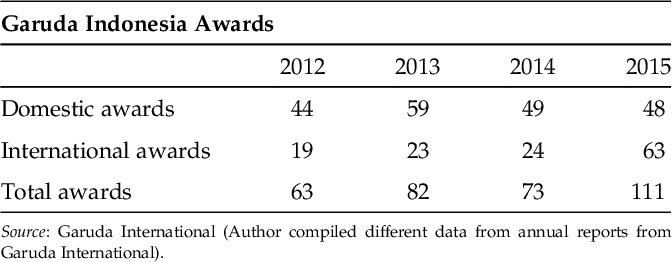

The reputation of Garuda Indonesia domestic and international also was recognized by the community, organization, and also consumer itself with some data below showing the increase in the Garuda Indonesia’s reputation.

Beside the brand reputation above, the cabin crew was awarded as the world’s best cabin staff by Skytrax for two consecutive years (2014–2015). Skytrax is a United Kingdom-based consultancy, conducts research and surveys on rating various commercial airlines, airports, in-flight entertainment, on-board catering, cabin crew, and other air-travel-related service issues. In 2013, this airline was at number 7 and it was not even near the “Top 10” before that. Garuda Indonesia increased its overall quality significantly from none before 2005 to be in the Top 10 by 2015. Skytrax found Garuda Indonesia in the Top Ten World’s Best Airline survey in three consecutive years — 2013 (#7), 2014 (#7), and 2015 (#8).

Finally, in 2015 Garuda Indonesia joined the ranks of the 5-STAR airlines in the world together with other Top 5-STAR Airlines. Garuda Indonesia changed significantly in the product, service, perception, image, and commitment to offer the best possible service and improve all aspects of the company.

Garuda Indonesia tried to fulfill the basic need of its customers; in the process it also built the image and perception of the brand.

For the next five years, Garuda Indonesia has a long-term strategy called “Sky Beyond” with three core programs with Excellent Indonesian Hospitality as its foundation to maximize returns with group synergy. The target of the company by 2020 is “20-10-5” goal, meaning that by 2020 the company should achieved 10 billion USD in revenues with 5% profit margin. With sustainability of profits as one of its key aims, the long-term business aim is to ensure that the company and the shareholders can build and support the development of the company for long run profitability and growth.

1. What are the main challenges that Garuda Indonesia faced before 2005?

2. What did they do to realize the main problems that time?

3. How did Garuda Indonesia gain customer’s trust after realized the main problems?

Answer guide Q1:

Company produced enough profit to develop the company business and to offer good product and services to fulfill the consumer need and want and their expectation. The situation impacted to Garuda Indonesia competitiveness in the market and fail to get more passenger and to sell more product and services in the premium price. The company’s ability in terms of production also really poor with the bad reputation in “On-Time Performance” brought situation more complex.

The reputation of the Garuda Indonesia Brand was very bad at that moment and far away from the Top 100 Airline in the world with the image as poor product and services, always delay and as perceived as the low-level product and services in industry.

Answer guide Q2:

They did survey in the middle-up market on the Airline Industry. The result: Indonesian’s consumer chose the airline base on some criteria with the reputation as the main reason. Reputation mean has good positioning in the market, more premium product and good services, and most of people recognize them as part of the lifestyle and bring good perception in the society that they become part of the middle-up level when they use the good reputation Airline.

Answer guide Q3:

Garuda Indonesia decided to transform the business, organization, financial, and operational services. The aim is to reach the promising target market, with target premium product and premium price. The program is to rebuild Garuda Indonesia in 2005 as the Quantum Leap Program

After five years of implementation of the Quantum Leap Program starting with a very basic program for survival (Math especially in the product and services program enhancement), Garuda Indonesia made big changes in the entire based on the consumer needs and expectations.

Offering new Aircraft latest model, supported with information technology and with the Indonesian hospitality as the main gun to the market with uplifting the cabin crew attitude and behavior, improving the ground crew and facilities, improvement in the product and service reliability, security, and safety record, “On-Time Performance” are the most basic changing had been made by Management.