D

DACHSTEINWEIBL: The “Woman of the Dachstein Massif ” (the Drei-Länder-Berg, the “Mountain of Three States”) is a witch who is small in size, wrinkled, and covered with warts. Her appearance is a portent of bad weather or a catastrophe. It is said she was once a haughty, evil cowherd who was transformed into a hideous woman and condemned to wander until the Final Judgment.

Adrian, ed., Alte Sagen aus dem Salzburger Land, 89–90.

Adrian, ed., Alte Sagen aus dem Salzburger Land, 89–90.

DAGR (“Day”): The son of Nótt (“Night”) and Dellingr, he is the personification of day. He is the ancient founder of the line of Döglingar, which includes Helgi, murderer of King Hundingr. Dagr rides the horse Drasill.

DÁINN (“Death”): 1. Dwarf who, with Nabbi, crafted the boar Hildisvíni, on which Freyja rides. 2. One of the four stags that graze among the branches of Yggdrasill.

DARK ELVES:  DÖKKÁLFAR

DÖKKÁLFAR

DESTINY: Although English has only five words (the other four are fate, fortune, lot, and luck) to express this concept, ancient Scandinavian had at least fifteen terms to express the notion of fate. This range of expressions testifies to the importance of the concept and its many subtleties: destiny can be neutral, objective, subjective, active or passive, beneficial or harmful, collective or individual, personified, symbolic, and so forth. It is therefore no surprise to find its echo in the mythology. It is embodied by the Dísir (Dises) or Nornir (Norns), the latter group being often depicted as spinners.

URÐR, WURD

URÐR, WURD

Régis Boyer, “Herfjötur(r),” in Visages du destin dans les mythologies: Mélanges Jacqueline Duchemin, ed. François Jouan (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1983), 153–68; Boyer, “Fate as a ‘Deus Otiosus’ in the Íslendingasögur: A Romantic View?” in Sagnaskemmtun: Studies in Honour of Hermann Pálsson, ed. Rudolf Simek, et al. (Vienna and Cologne: Böhlau, 1986), 61–67.

Régis Boyer, “Herfjötur(r),” in Visages du destin dans les mythologies: Mélanges Jacqueline Duchemin, ed. François Jouan (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1983), 153–68; Boyer, “Fate as a ‘Deus Otiosus’ in the Íslendingasögur: A Romantic View?” in Sagnaskemmtun: Studies in Honour of Hermann Pálsson, ed. Rudolf Simek, et al. (Vienna and Cologne: Böhlau, 1986), 61–67.

DIABOLICAL HUNTSMAN: It was during the thirteenth century, thanks to the writing of the Cistercian monk Caesarius von Heisterbach (Dialogus miraculorum atque magnum visionum, XII, 20), that we find mention of a diabolical huntsman in the following story. A priest’s concubine on her deathbed urgently requested that a new pair of sturdy shoes with heels be made for her and placed on her feet, which was done. The following night, a good while before dawn and when the moon was still shining, a knight was riding with his squire. They heard the cries of a woman in distress and were wondering who it could be when a woman began running toward them at top speed, screaming, “Help me, help me!” The knight immediately dismounted, drew a circle around himself with his sword, and set the woman, whom he knew well, inside it. She was wearing only a shirt and the shoes described above. Then, all at once, they heard a far-off noise that resembled that of a huntsman blowing his horn in the most horrible way, and the howls of his hunting dogs preceding him. When the woman heard these noises, she began trembling from head to foot, but the knight, having learned the cause, entrusted his horse to his squire, wrapped the locks of the woman’s hair around his left hand, and brandished his sword with his right. When the infernal huntsman drew near, the woman began screaming at the knight, “Let me go! Let me go! Look: he is coming!” He continued holding on to her with all his might. But the woman continued struggling until her hair tore loose, and she fled. Racing in pursuit, the demon caught her and threw her across his horse so that her arms and head hung down over one side and her legs down over the other. A short time later the knight saw the demon carrying off his prey. The knight returned to the village in the morning, told people of what he had seen, and showed them the clump of hair. As no one wished to believe him, they opened the grave and all could see that the woman inside no longer had any hair.

Lecouteux, Phantom Armies of the Night, 56–64.

Lecouteux, Phantom Armies of the Night, 56–64.

DIALA (pl. Dialen): The Diala is a wild woman in Swiss folk traditions. They are incredibly beautiful, kind, and helpful, and they live in caves where they sleep on beds of moss. Unfortunately, they also have goat feet. They are also called Waldfänken.

Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 63–65, 129, W. Lynge, “Dialen, Unifrauen und Vilen: Motivgeschichtliches zu den weiblichen Sagengestalten mit tierfüßen im Alpenund Karstbereich,” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 60 (1957): 194–218.

Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 63–65, 129, W. Lynge, “Dialen, Unifrauen und Vilen: Motivgeschichtliches zu den weiblichen Sagengestalten mit tierfüßen im Alpenund Karstbereich,” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 60 (1957): 194–218.

DÍAR (“Gods”): This is the name given by Snorri Sturluson to the group of twelve priests in Ásgarðr who serve Odin. “They were to have charge of sacrifices and to judge between men. . . . All the people were to serve them and show them reverence” (Ynglinga Saga, chap. 2, in Sturluson, Heimskringla, trans. Hollander).

DIDKEN (sg. Didko): These are elementary spirits of the region of Galicia in eastern Europe; their name makes them akin to the Slovak and Russian Dedusko and the Diblik (imp) in Bohemia. They appear in the form of a dandy with a magpie’s tail, tight pants, and a top hat. They are able to transform into dogs, cats, mice, and so forth. Their lives can only be cut short by lightning or by a rapid right-to-left movement of the hand of a human being. They can be recognized by their shining green eyes. There are two different kinds of these creatures: one type lives in a house; the other is wild and makes contracts with the master of the household. The Didken will accept old clothes, a corner in which to sleep, and food that does not contain any salt. If the contract is respected, they make sure the house is run properly and watch over the animals. When the master of the house dies, they will enter the service of his heirs without a contract, but if they are turned down or are not acknowledged, they will cause such a racket in the house that the inhabitants will be forced to leave. The Didken will then depart to live in the swamps, where they will become wild and wicked. They will nonetheless still continue to offer their services. Whoever wishes to take them up on their offer must cook nine round loaves without salt on the eve of Saint George’s Day, go to the crossroads at night, and, speaking certain spells, invite the Didken to come eat the bread.

This kind of creature can also be obtained from an egg that should be buried beneath the threshold to the yard; a Didko will hatch from it nine years later.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 238–40.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 238–40.

DÍSABLÓT (“Sacrifice to the Dises”): Offerings made to the Dísir (Dises) at the start of winter, mid-October in Norway, and in February in Sweden. Little is known about this expression of domestic worship, except that it featured a banquet. Most likely the purpose was to gain the favor of the Dises, understood here as fertility deities. The origin of these minor gods is certainly Indo-European, and the Germanic Dises have their counterpart in the Vedic dhisanās.

DISES

DISES

DISAPPEARANCE:  ABDUCTION

ABDUCTION

DÍSARSALR (“Hall of the Dise”): The name of a temple in Uppsala (Sweden) consecrated to the Dises. The use of the singular here is strange and unusual as we generally see the plural form, Dísir, used as the Dises are an undifferentiated entity.

DISES (Old Norse dís, pl. dísir): Female deities who may be identical to the Idisi cited in the First Merseburg Charm and whose name can also be found in the work of Tacitus, in Idisiaviso, the name of a plain where Germanicus met Arminius (Hermann) in battle. The tradition is quite muddled, because the Dises are much like the valkyries and the Norns (the Germanic Fates) and play the role of guardian spirits as well, which makes them akin to the fylgjur. It is said they rush up when children are born, which likens them to Roman fairies. The Dises were also regarded as local land spirits that governed fertility, as testified by the landdísasteinar (stones of the Dises of the land) in the Ísafjörður region of northwestern Iceland. Several place-names also attest to the reality of the worship they received. The Dises are probably best interpreted in the context of the mother goddesses. It should be noted that the goddess Freyja is called vanadís, the “Dise of the Vanir,” and the giantess Skaði is called öndurdís, the “Dise of the Skis.”

Boyer, La Grande Déesse du Nord, 77–78.

Boyer, La Grande Déesse du Nord, 77–78.

DIVINE TWINS: The Germanic past offers a wide variety of images of divine twins, and there are also many sibling pairs (such as Freyr and Freyja, Hengist and Horsa, Ibor and Aio, etc.). These are primarily twin myths and are not directly connected with the Dioscuri of classical antiquity.

ALCI, HENGIST and HORSA, IBOR and AIO

ALCI, HENGIST and HORSA, IBOR and AIO

Monfort, Les Jumeaux dans la littérature et les mythes germaniques; Ward, The Divine Twins; François Delpech, “Les jumeaux exclus: cheminements hispanique d’une mythologie de l’impureté,” in Les problèmes de l’exclusion en Espagne (XVIe–XVIIe siècles), ed. Augustin Redondo (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1983), 177–203; Jaan Puhvel, “Aspects of Equine Functionality,” in Myth and Law among the Indo-Europeans, ed. Puhvel, 159–92; Hellmut Rosenfeld, “Germanischer Zwillingskult und indogermanischer Himmelsgottglaube,” in Märchen, Mythos, Dichtung: Festschrift zum 90. Geburtstag Friedrich von der Leyens am 19. August 1963, eds. Hugo Kuhn and Kurt Schier (Munich: Beck, 1963), 269–86.

Monfort, Les Jumeaux dans la littérature et les mythes germaniques; Ward, The Divine Twins; François Delpech, “Les jumeaux exclus: cheminements hispanique d’une mythologie de l’impureté,” in Les problèmes de l’exclusion en Espagne (XVIe–XVIIe siècles), ed. Augustin Redondo (Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne, 1983), 177–203; Jaan Puhvel, “Aspects of Equine Functionality,” in Myth and Law among the Indo-Europeans, ed. Puhvel, 159–92; Hellmut Rosenfeld, “Germanischer Zwillingskult und indogermanischer Himmelsgottglaube,” in Märchen, Mythos, Dichtung: Festschrift zum 90. Geburtstag Friedrich von der Leyens am 19. August 1963, eds. Hugo Kuhn and Kurt Schier (Munich: Beck, 1963), 269–86.

DODAMANDERL (neut.): This is the personification of death in the form of a thin, ugly man with a long nose and a hunchback. The Dodamanderl is the subject of many songs, some of which claim he is the son of the Dodamon.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 71–75.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 71–75.

DODAMON (masc.): The personification of death, the Dodamon appears fleetingly on a golden horse at certain times, often with a scythe or a long white nightcap. It is said that whoever sees him on his horse shall be blessed with happiness, but if seen with his scythe or nightcap, the individual will have no more than three years left to live.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 280–82.

Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 280–82.

DOFRI: A giant that lives in the mountain bearing his name, the Dofrafjall. His name appears in the þulur lists and in Haralds þáttr hárfagra (The Tale of Harald Fairhair).

DOG: This animal is the first thing one meets at the gate to Hel ( GARMR), and his chest is covered in blood. He bears strong resemblance to the Greek Cerberus. Mention is also made in the mythology of the dogs Gífr and Geri, who guard the home of Menglöð, a hypostasis of the goddess Freyja. In more recent Scandinavian

Yule

customs, a figure wearing a dog mask appears in holiday processions. It should finally be noted that the remains of dogs have been discovered in the funeral mounds. The hero Helgi is famous for slaying King Hundingr—a name that literally means “the descendant of the dog,” being composed of hund, “dog,” plus the suffix -ingr/-ungr, which indicates genetic descent. (Incidentally, the same type of construction can be seen in the name of the Merovingians, the “descendants of Meroveus.”) A name like Hundingr carries totemic associations, for which there is much supporting evidence.

GARMR), and his chest is covered in blood. He bears strong resemblance to the Greek Cerberus. Mention is also made in the mythology of the dogs Gífr and Geri, who guard the home of Menglöð, a hypostasis of the goddess Freyja. In more recent Scandinavian

Yule

customs, a figure wearing a dog mask appears in holiday processions. It should finally be noted that the remains of dogs have been discovered in the funeral mounds. The hero Helgi is famous for slaying King Hundingr—a name that literally means “the descendant of the dog,” being composed of hund, “dog,” plus the suffix -ingr/-ungr, which indicates genetic descent. (Incidentally, the same type of construction can be seen in the name of the Merovingians, the “descendants of Meroveus.”) A name like Hundingr carries totemic associations, for which there is much supporting evidence.

In folk belief the dog is often the form assumed by the soul in torment, as in the story related in by the fifteenth-century Rhenish peasant Arndt Buschmann.

Lecouteux, ed. and trans., Dialogue avec un revenant (XVe siècle).

Lecouteux, ed. and trans., Dialogue avec un revenant (XVe siècle).

DÖKKÁLFAR (“Dark Elves”): These beings are only ever mentioned in the Snorra Edda. They are almost certainly dwarves and not elves. They are blacker than pitch and live in the world that bears their name, Svartálfheimr. They are mortal enemies of the ljósálfar, the Light Elves. They are also the smiths who forge the treasures of the gods.

DÓMALDI: A mythical Swedish king from the major family of the Ynglings (the Ynglingar, the descendants of Yngvi-Freyr). Following three years of famine, he was slain by his subjects, the Svear. Snorri Sturluson reports: “The chieftains held a council, and they agreed that the famine probably was due to Dómaldi, their king, and that they should sacrifice him for better seasons” (Ynglinga saga, chap. 15, in Sturluson, Heimskringla, trans. Hollander).

DONANADL: This is the name of a Tyrolean dwarf. He is generally regarded as being very good-hearted. He is old and seems of great age and is also always clad in rags. He most often appears by himself but is sometimes accompanied by others like him.

If a Donanadl appears at any time in the high pastures where the flock is grazing for the summer, then one can be sure that the livestock will be protected from all accidents, and their milk production will be greater than is the case in other meadows that do not enjoy the protection of such a kind and beneficial spirit. If snow falls at any time during the summer they will guide the livestock away from the steep and slippery slopes, where they are at risk of falling, to safer pastures. The Donanadl often visit the chalets where they eat with the shepherds, cowherds, and milkers when offered food. They often vanish suddenly and without a trace from the company of those with whom they are feasting. During the winter they live in the mangers of the stables. If the cowherd is late getting to the barn he can be certain to find the spirits already taking care of the animals and giving them large quantities of fodder. Although they are quite prodigal, they are never lacking for anything.

Adrian, ed., Alte Sagen aus dem Salzburger Land, 90–92.

Adrian, ed., Alte Sagen aus dem Salzburger Land, 90–92.

Fig. 19. Meeting the Donanadl

DONAR (“Thunder”): Name for Thor among the southern Germans. In Old English the name is Þunor. In the Germano-Roman continental inscriptions, Donar is frequently conflated with Hercules, in conformance with the interpretatio romana of the Germanic gods. His name can be found in the vernacular names for Thursday, such as Old English Þunresdæg and Old High German Donarestâc. In 725, Saint Boniface destroyed his sacred oak in Geismar (Hesse, Germany). An Old Saxon baptismal vow for rejecting paganism says: “I renounce Thunær, Uuôden, and Saxnôt, and all the demons that are their companions.”

THOR

THOR

DOPPELSAUGER:  ZWIESAUGER

ZWIESAUGER

DÓRI: The name of a dwarf mentioned in strophe 15 of Völuspá in the Poetic Edda. Dóri appears as one of the thirteen dwarves in J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937). The name has been variously interpreted as meaning “The Harmer,” “The Fool,” or “The Peg.”

Lotte Motz, “New Thoughts on Dwarf-Names in Old Icelandic,”

Frühmittelalterliche Studien 7 (1973): 100–117.

Lotte Motz, “New Thoughts on Dwarf-Names in Old Icelandic,”

Frühmittelalterliche Studien 7 (1973): 100–117.

DRAC, DRACHE: The drac (cf. German Drache, “drake, dragon”) is connected with money and brings fortune to the house where he has chosen to live. Drac is a generic term that is applied in the Germanic regions to an igneous phenomenon that is often ascribed with demonic qualities—hence its name of “devil” (Teufel)—or is attributed to elves, for it is often simultaneously called an alf or a kobold. Depending on the country and region, it basically has the meaning of “spirit” and is then given a connection to certain fruits of the earth.

When the drac flies through the air and enters the house through the chimney or through a hole in the roof he has the appearance of a long, fiery pole, but he is also described as a little man wearing a red coat—hence his name of Rödjackte in Pomerania. His igneous nature emerges clearly from many names found in Lower Saxony such as “Burning Tail” (Gluhschwanz, Glûswanz), which suggests a trail of fire, and “Red Iron” (Glûbolt). In Westphalia the names that are based on the word Brand, “fire,” refer to the same notions. Sometimes the drac looks like a simple ball of fire or a flaming star. This connection with flames explains why he is attributed in some places with the same form as the devil or a sorcerer, and his preferred abode is regularly assumed to be the chimney or behind the stove—a location that in Germany bears the significant name of “Hell” (Hölle).

Regionally his other aspects are those of the common household spirits. The drac often assumes the form of an animal—such as a rooster, a hen, or a lizard—and a variety of colors, both depending on the load he is carrying back to his master. If he is sparkling, then he is carrying silver; if he is dark or gray, he is transporting vermin; when he is golden, he is loaded down with gold or wheat; and so on. Most of the time he is acquired by concluding a pact with the devil, but it is also said that the drac is born from a yolkless egg. He begins life by causing problems in the barns and stables before flying away to lead his life as a drac. When an egg like this is found it must be thrown over the house so it breaks. In Latvia it is believed to be the outer soul, meaning the double (alter ego) of an evil man, a sorcerer, or a magician. The drac’s nature is ambiguous, because he enriches his owner at the expense of his neighbors, whose property he steals and brings back. A drac is therefore feared by people at the same time as they wish to own one. This ambiguity is linked, of course, to his being conflated with the devil and his retinue, to sorcerers and other magicians.

The drac must be given offerings—such as cakes, bits of meat, milk, and millet gruel—that are placed in the hearth or on the stove. These are regarded as his wages for his activity. If one forgets to “pay” him, his vengeance is terrible and reflective of his nature: he sets fire to the house! But if his services are unsatisfactory, it is possible to punish him.

Lecouteux, The Tradition of Household Spirits, 56, 143, 153–55, 162–63, 185–86.

Lecouteux, The Tradition of Household Spirits, 56, 143, 153–55, 162–63, 185–86.

DRACHENKOPP: This is a corruption of a Greek word dracontopodes, “dragon-footed,” used to describe the feet of the giants in ancient mythology and, later, a serpent with a human head. This is part of a scholarly tradition, passed on by the Physiologus, the most famous of all the bestiaries, and by the thirteenth-century encyclopedists.

Lecouteux, “Drachenkopp,” Euphorion 72 (1978): 339–43.

Lecouteux, “Drachenkopp,” Euphorion 72 (1978): 339–43.

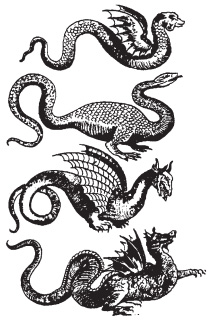

DRAGON: The most dreadful monster of all is the dragon, the largest of all reptiles. “When it comes out of its lair,” says Isidore of Seville, “he does it so roughly that it makes the air glow as if it were on fire; he has a large head, a crest, a narrow mouth from which its breath and tongue emerge; its strength is in its tail and not its teeth, and it kills by the blows it makes rather than its bite.” This description is that of naturalists and scholars, who do not attribute wings or feet to the beast. Logically examining the dragon’s anatomy, Albertus Magnus showed that it could not have feet, “because with such length, it could not move forward with a small number of feet.” This is probably why more than one author claimed the beast had six, twelve, and even twenty-four paws. Discussing wings, Albertus admits it could have them, but that they needed to be immense and membraneous, he adds; otherwise the wings would be unable to carry it. Some scholars believed that dragons had a kind of mane, but only Bartholomeus Anglicus thought it had teeth.

Fig. 20. Types of dragons. Konrad Gessner, Schlangenbuch, Zurich, 1589.

The image of the dragon in entertainment literature hardly coincided with these minimal descriptions. At the beginning of the thirteenth century Wirnt von Grafenberg provided the best description of the monster.

Its head was enormous, black, and shaggy; its beak was bare, a fathom long and a yard wide, pointed in front and sharp as a newly whetted spear; in its jaw were teeth like the tusks of a boar. Broad horny scales covered it, and a sharp spine—the sort with which a crocodile cuts ships in two—went from head to tail.

The dragon had a long tail—as dragons do. . . . The dragon had a comb like a rooster’s, but huge; its belly was green, its eyes red, its sides yellow; its body was round as a candle, and the sharp spine was pale yellow; its two ears were like those of a mule. The dragon’s breath was foul and stank worse than carrion that has lain for a long time in the hot sun. Its griffin-like feet were ugly and as hairy as a bear’s. It had two beautiful wings with feathers like those of a peacock. Its neck was bent down low to the ground, and its throat was as knotted as a mountain goat’s horn (Wigalois, 5038–74).

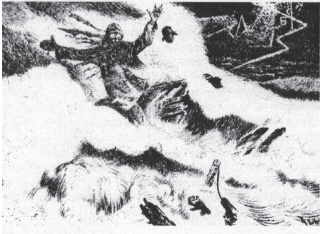

Fig. 21. Combat of a valiant knight (Harald) against a dragon. Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, Rome, 1555.

According to the Legenda Aurea (Golden Legend) by Jacobus de Voragine, the dragon infects the air, poisons wells, and casts its seed into fountains to incite the lust of men; it is a scourge to humankind and to animals. The bestiaries present it as the enemy of the panther, elephant, and lion. This is the result of a symbolic interpretation that was common among Christian writers: these three animals are said to represent Adam and Eve, God, and Jesus, whereas the dragon is naturally the embodiment of the image of the devil.

FÁFNIR

FÁFNIR

Sansonetti, Chevaliers et Dragons, 57–90; Lecouteux, “Der Drache,” Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum 108 (1979): 13–31; Lecouteux, “Seyfrid, Kuperan et le dragon,” Études Germaniques 49 (1994): 257–66; Tomoaki Mizuno, “The Conquest of a Dragon by the Stranger in Holy Combat: Focusing on the Mighty Hero Beowulf and Thor,” Studies in Humanities, Culture and Communications 36 (2002): 39–66; Lutz Röhrich, “Drache, Drachenkampf, Drachentöter,” in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, vol. III, col. 787–820; Paul Beekman Taylor, “The Dragon’s Treasure in Beowulf,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 98 (1997): 229–40.

Sansonetti, Chevaliers et Dragons, 57–90; Lecouteux, “Der Drache,” Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum 108 (1979): 13–31; Lecouteux, “Seyfrid, Kuperan et le dragon,” Études Germaniques 49 (1994): 257–66; Tomoaki Mizuno, “The Conquest of a Dragon by the Stranger in Holy Combat: Focusing on the Mighty Hero Beowulf and Thor,” Studies in Humanities, Culture and Communications 36 (2002): 39–66; Lutz Röhrich, “Drache, Drachenkampf, Drachentöter,” in Enzyklopädie des Märchens, vol. III, col. 787–820; Paul Beekman Taylor, “The Dragon’s Treasure in Beowulf,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 98 (1997): 229–40.

DRAKOKKA: Name of a familiar Norwegian spirit. It possesses magical powers and brings wealth. Since the early Middle Ages it was said to work in the service of sorcerers and other magicians.

Bø, Grambo & Hodne, Norske Segner, no. 5; Edvardsen, Gammelt nytt i våre tidligste ukeblader, 67.

Bø, Grambo & Hodne, Norske Segner, no. 5; Edvardsen, Gammelt nytt i våre tidligste ukeblader, 67.

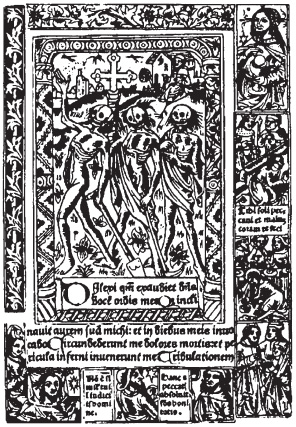

DRAUGR (“Revenant”): According to ancient belief, the Double of a dead man—his physical alter ego—continues to live in the tomb and will leave it if he has any reason to be upset with his fate. This ill-intentioned dead person can cause the death of people and livestock. To get rid of a draugr, it is necessary to burn its body completely and even sometimes immerse its ashes in the sea or running water. There is ample evidence for the fear of revenants in all of the Norse and Germanic countries. Archaeology has revealed that this is an extremely ancient belief: mutilated cadavers have been discovered in graves—a decapitated corpse with the head placed at its feet, for example—and others have been bound so they could not return to trouble the living. The Germanic revenant possesses the unique feature of being entirely corporeal with the power to melt away into the ground and vanish as if by enchantment; but if he has been wounded, the marks of those wounds will be found on his body if it is exhumed. Contrary to mistaken opinion, the “living dead” do not exist: what comes back is only the physical Double.

Fig. 22. Revenants of drowning victims appear during shipwrecks. Illustration from Ronald Grambo’s book Gjester fra Graven.

In northern Germany revenants are called Gongers (sg.: der Gonger, “he who goes”) and are the dead who cannot rest in peace, either because they are missing a certain object or because they have not atoned for a misdeed committed while they were still alive (such as moving a boundary marker, committing suicide, etc.). Their hand should not be shaken as it will then burn up and come off the arm. Drowning victims are also Gongers; they do not appear to their relatives but rather to their immediate descendants.

Revenants have long been a staple in literature, whether in Gottfried August Bürger’s 1774 ballad, Lenore, or the medieval Danish ballad of Aage and Else, or works such as Theodor Storm’s 1888 novella Der Schimmelreiter (The Rider on the White Horse).

Fig. 23. Illustration from the Dit des trois morts at des trois vifs, Heures à l’usage de Rome, Paris, circa 1487

AAGE and ELSE, LENORE, NACHZEHRER, SCHIMMELREITER

AAGE and ELSE, LENORE, NACHZEHRER, SCHIMMELREITER

Boyer, La Mort chez les anciens Scandinaves; Lecouteux, ed. and trans., Dialogue avec un revenant (XVe siècle); Lecouteux, Phantom Armies of the Night; Lecouteux, The Return of the Dead; Lecouteux, Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies; Lecouteux and Marcq, Les Esprits et les Morts; Grambo, Gjester fra graven; Müllenhoff, Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzogthümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg, no. 251; Nielsen, ed., Danske Folkeviser, vol. II, 51–71 (Danish ballads); Nilssen, Draugr; Walter, ed., Le Mythe de la Chasse sauvage dans l’Europe medieval; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1854– 1867. C. N. Gould, “They Who Await the Second Death,” Scandinavian Studies and Notes 9 (1926/1927): 167–201 (on the connection between revenants and dwarves); Lecouteux, “Gespenster und Wiedergänger: Bemerkungen zu einem vernachlässigten Forschungsfeld der Altgermanistik,” Euphorion 80 (1986): 219–31; Lecouteux, “Typologie de quelques morts malfaisants,” Cahiers slaves 3 (2001): 227–44; Lecouteux, “Wiedergänger,” in Lexikon des Mittelalters, vol. Ix, col. 79–80; Eugen Mogk, “Altgermanische Spukgeschichten,” Illbergs neue Jahrbücher für das klass. Altertum 43 (1919): 103–17; Ingeborg Müller, and Lutz Röhrich, “Der Tod und die Toten,” Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967): 346–97 (catalogue of the themes); Günter Wiegelmann, “Der lebende Leichnam im Volksbrauch,” Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 62 (1966): 161–83.

Boyer, La Mort chez les anciens Scandinaves; Lecouteux, ed. and trans., Dialogue avec un revenant (XVe siècle); Lecouteux, Phantom Armies of the Night; Lecouteux, The Return of the Dead; Lecouteux, Witches, Werewolves, and Fairies; Lecouteux and Marcq, Les Esprits et les Morts; Grambo, Gjester fra graven; Müllenhoff, Sagen, Märchen und Lieder der Herzogthümer Schleswig, Holstein und Lauenburg, no. 251; Nielsen, ed., Danske Folkeviser, vol. II, 51–71 (Danish ballads); Nilssen, Draugr; Walter, ed., Le Mythe de la Chasse sauvage dans l’Europe medieval; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1854– 1867. C. N. Gould, “They Who Await the Second Death,” Scandinavian Studies and Notes 9 (1926/1927): 167–201 (on the connection between revenants and dwarves); Lecouteux, “Gespenster und Wiedergänger: Bemerkungen zu einem vernachlässigten Forschungsfeld der Altgermanistik,” Euphorion 80 (1986): 219–31; Lecouteux, “Typologie de quelques morts malfaisants,” Cahiers slaves 3 (2001): 227–44; Lecouteux, “Wiedergänger,” in Lexikon des Mittelalters, vol. Ix, col. 79–80; Eugen Mogk, “Altgermanische Spukgeschichten,” Illbergs neue Jahrbücher für das klass. Altertum 43 (1919): 103–17; Ingeborg Müller, and Lutz Röhrich, “Der Tod und die Toten,” Deutsches Jahrbuch für Volkskunde 13 (1967): 346–97 (catalogue of the themes); Günter Wiegelmann, “Der lebende Leichnam im Volksbrauch,” Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 62 (1966): 161–83.

DRAUPNIR (“Dripper”): Ring or arm ring owned by Odin. It is called “Dripper” because on every ninth night eight more rings that are equal to it in weight “drip” from it, thus increasing wealth. It was crafted by the dwarves Brokkr and Sindri. Odin placed it on Baldr’s funeral pyre.

Draupnir is also the name of a dwarf mentioned in the Eddic poem Völuspá (The Prophecy of the Seeress).

DRÍFA (“Snowdrift”): This name, which is probably that of a giantess, appears among the ancestors of the mythical king Fornjótr in the text Hversu Nóreg byggðisk (part of the fourteenth-century Icelandic manuscript Flateyjarbók) and is a personification of winter.

DRUDE, TRUTE (fem.): One of the names for “nightmare” in the Austrian-Bavarian region. In Lower Austria the Drude is an otherwise nondescript woman who is obliged to go out at night and sit with all her weight on a person, crushing the victim without mercy. Once this has been done, the Drude changes appearance and becomes old and ugly; she is pale and thin, although of increased weight. Her feet have three large toes, one of which points backward. She can enter anywhere, through the window or through a keyhole, and no holy object can hinder her. She can even transform into a feather. According to some, she does not speak or make any noise, while others claim that she is immediately identifiable by the slight slide of her footsteps. Generally she comes to sit on the chest of a sleeper around midnight. According to one legend the Drude is an ancient princess who has been unable to find rest for a thousand years and squeezes sleeping men.

Women whose fate it is to become a Drude know this but never reveal it to anyone. When they leave to crush someone their body remains in place, and it is only their spirit that departs; therefore, they do not know who it is they have attacked. To get rid of Druden it is necessary to throw a pillow at their feet, which paralyzes them, or else to say, if possible, “Come tomorrow for salt!” while one is being crushed, and the attacker will soon be identified, for she will return the next day to the site of her attack. It is also possible to draw a pentacle over all the openings of the house or to bind the latches with a string.

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 30; Heyl, Volkssagen, Meinungen und Bräuche aus Tirol, 288–89, 430–31; Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 268–72; Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 112, 481.

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 30; Heyl, Volkssagen, Meinungen und Bräuche aus Tirol, 288–89, 430–31; Vernaleken, Mythen und Bräuche des Volkes in Österreich, 268–72; Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 112, 481.

DURANT (masc.): The name of a plant that, when attached to infants, prevents demons from substituting their progeny for that of the humans.

CHANGELING

CHANGELING

DUTTEN: A people that is said to have lived in the forest of Minden, Westphalia. They were pagans and made pilgrimages to a pond between Minden and Todtenhausen. They offered sacrifices to their gods in this sacred place and bathed in its blessed waters.

Weddingen and Hartmann, Sagenschatz Westfalens, 12.

Weddingen and Hartmann, Sagenschatz Westfalens, 12.

DWARF NAMES: The most common name for dwarves is Zwerg, which means “twisted” in a physical sense, but consequently in a “moral” one as well. The form of the word varies according to region: in northern Germany we have Twarg; in southern Germany, Zwargi; in Westphalia, Twiärke; Thuringia, Tweärken; Querlich and Querge in the Harz; and Querchlinge in Hesse, among others. A somewhat less common term is Wicht (“thing,” “being”), which is used to form many compound words like Wichtelmännchen. Dutch speakers use alvermannekens (from alv, “elf ”), kabouter (masc.), and kaboutervrouwtjes (fem.), heihessen, and hussen.

The next group of names consists of compound words using erd-, “earth,” indicative of the chthonic nature of dwarves. Erdmantje in eastern Frisia designates a gray dwarf, who is spectral and wicked. Erdmünken are household spirits in the former duchy of Oldenburg; their queen was named Fehmöhme. Then there are the Eirdmannekes, Aardmannetjes, and Sgönaunken in Westphalia, while the Fegmännchen (“the sweeper”) in Bernese Oberland is a land spirit that lives in the mountains. The large family of underground dwellers in northern Germany bears the names Odderbaantjes, Odderbaanki, Unnerseke, Onnerbänkissen, Unnervœstöi, Önnereske, Unnerborstöi, Uellerken, and Unnerreizkas (Pomerania); there are also the amical musicians the Ellieken (in the Mark, the boundary lands of Germany northeast of Berlin).

The names of dwarves and household spirits can be coined from first names: Heinzelmännchen (from Heinrich), Johannes (John), Petermännlein (Peter), Ludi (little Louis), Wolterken (from Walter), Niss/Nisepuk (little Nicholas), Chimeke/Chimgen/Schimmeke (“little Joachim”), who was famous for killing, dismembering, and cooking an insolent kitchen lad of Mecklenburg Castle. Their names can also be drawn from the places they reside (Kellermännchen, “little man of the cellar”; Pfarrmännel, “wee man of the rectory”; Ofenmänchen, “little man of the oven”), the times when they are active (Nachtmännlein, “little night-man”), or else from their activity (Futtermännchen/Fueterknechtli, from Fütter, “fodder”; or Käsmandel, from “cheese” or “chalet” because Kaser/Käser can mean both of these things, who is described as a gray little man with a pale wrinkled face; Kistenmännchen (“wee man of the treasure”), or, lastly, from the color of their clothes (Graumännchen/ Gro mann, “little gray man”; Rotjäksch, “red jacket”). In the fifteenth century the Silesian stetewaldiu was “he who governs the premises,” a household spirit.

Their size is expressed in the names Däumling (“little thumbling”) and Fingerling (Prussian for “finger”). Their appearance is reflected in names like Dickkopf (“fathead”), Kröppel (“goitrous”), Boyaba (“small boy”), and lütje lüe (“wee folk”).

There are a plethora of names in the Scandinavian countries, and there is not always a distinction made between dwarves and local land spirits. In Denmark the names include dværg, Lille Liels, Nis Puge, Puge, and Gaardbo (Gaardbonisse, Gaardbuk); in Iceland we have dvergr, álfr, and the collective huldufólk, the “hidden folk”; in Norway, Tuss(e), Tomte (Tomtegubbe), Gardsvord (gardsbonde), Tunkall, Tunvord, and huldrefolk; in Sweden, Gårdsrå, Tomte (Tomtebise, Tomtegubbe), and Nisse (Goa Nisse, Nisse-godrång).

Others names found in the German-speaking countries of Switzerland, Germany, and Austria include Bergmännlein, Donanadl, Gotwerg, Gotvährinne, Käsmandel, Nebelmännlein, Nörglein/Norgen (“grumpy”), Querre, Schrattel/Schrätteli, Spielmännli, Twirgi, Venediger, and Zwerg.

All of these names have multiple dialectal variations that are too numerous to list.

Lecouteux, Les Nains et les Elfes au Moyen Âge; Lindig, Hausgeister; Linhart,

Hausgeister in Franken.

Lecouteux, Les Nains et les Elfes au Moyen Âge; Lindig, Hausgeister; Linhart,

Hausgeister in Franken.

DWARVES (Old Norse dvergr; Old High German twerc; Old English dveorg): Contrary to the preconceived notions passed on by folklore, dwarves are not necessarily little: they can assume any size at will. “Dwarf ” is a generic term like “god” or “giant” and designates a race of malevolent beings, the opposite of elves. Etymologically speaking, their name means “twisted” both in body and mind.

According to the Poetic Edda, two dwarves, Móðsognir and Durinn, existed in the beginning, and they created a race in their image. When the gods created the world, they placed four dwarves at each of the four cardinal points to hold up the sky. According to Snorri Sturluson, dwarves were born from the decomposition of the giant Ymir’s corpse, then the gods gave these larvae a human face and intelligence.

Dwarves are skilled artisans and excellent smiths. They crafted the attributes of the gods: Thor’s hammer ( MJÖLLNIR), Odin’s spear (

MJÖLLNIR), Odin’s spear ( GUNGNIR), Freyr’s boat (

GUNGNIR), Freyr’s boat ( SKÍÐBLAÐNIR), Freyja’s necklace (

SKÍÐBLAÐNIR), Freyja’s necklace ( BRÍSINGAMEN), Sif’s hair, the ring Draupnir, and a boar with golden bristles. All these objects were endowed with wonderful powers. When the dwarves forged weapons for humans, the weapons were extremely destructive, like the famous swords Dáinsleif (“Dáinn’s Legacy,” Dáinn being a dwarf whose name means “death”) and Tyrfingr.

BRÍSINGAMEN), Sif’s hair, the ring Draupnir, and a boar with golden bristles. All these objects were endowed with wonderful powers. When the dwarves forged weapons for humans, the weapons were extremely destructive, like the famous swords Dáinsleif (“Dáinn’s Legacy,” Dáinn being a dwarf whose name means “death”) and Tyrfingr.

Dwarves are also magicians and enjoy such close relations with the dead that it is thought they may be the mythical transposition of evil dead men. There are many with names that are quite revealing in this regard: “Black,” “Deceased,” “Torpid,” “Death,” “Corpse,” “Cold,” “Buried beneath the Cairn,” and so forth. They are obviously chthonian—the light of day petrifies them—and bound to the lithic world. They all live in or beneath the stones, mounds, and mountains, which are all places regarded as havens for the dead of their empire, an opinion found in the story of King Herla. Like many chthonian beings, they are the keepers of great wealth and poetry ( KVASIR), which is metaphorically termed “dwarves’ drink.”

KVASIR), which is metaphorically termed “dwarves’ drink.”

Dwarves also have a connection with water ( ANDVARI), which makes them akin to their Celtic cousins, the leprechauns and the Afang.

ANDVARI), which makes them akin to their Celtic cousins, the leprechauns and the Afang.

Contrary to elves, which have associations with Freyr and the Æsir, dwarves have no connection to anyone, although they are suggestive of the same Dumézilian function as the Vanir (the third function, that of fertility/fecundity) but seem to embody its negative aspects. There is no clear dividing line between dwarves and giants: both are experts in magic and possess great knowledge ( ALVISS) and are connected to the dead. The patron of the dwarves could be Loki, whose nature fluctuates between that of a dwarf and that of a giant.

ALVISS) and are connected to the dead. The patron of the dwarves could be Loki, whose nature fluctuates between that of a dwarf and that of a giant.

Dwarves are also thieves ( ALÞJÓFR). An odd charm in Old English depicts a dwarf perceived as an unidentified misfortune that arrives in the form of a spider.

ALÞJÓFR). An odd charm in Old English depicts a dwarf perceived as an unidentified misfortune that arrives in the form of a spider.

In the epics and romances of Germany and England, dwarves retain their wicked character, manual dexterity, and their knowledge of the secrets of the Earth. They come in the guise of knights, old men white with age ( ALBERICH), or children. They dwell in wondrous hollow mountains illuminated by gems and live in hierarchical communities that apparently obey the same laws as men.

ALBERICH), or children. They dwell in wondrous hollow mountains illuminated by gems and live in hierarchical communities that apparently obey the same laws as men.

In Switzerland dwarves are called Gottvährinnen and Gotwergi (Valais); Spielmännli (Friburg Canton), because they play violin; Toggeli, Doggi, Tocki, Twirgi (Berner Oberland), Servans (Vaux Canton), and Zwerge.

Three kinds of dwarves—white, brown, and black—are found on the island of Rügen. Both the white and brown dwarves are kindly and cause no ill to anyone, but the white dwarves are the friendliest. The black dwarves are magicians and are worthless; they are deceitful and double-dealing. All of these dwarves particularly like to live in the mountains of the island.

Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 137–38; Lecouteux, Les Nains et les Elfes au Moyen Âge; Motz, The Wise One of the Mountain; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1437–52; Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 107–11, 118–24, 147–48, 322.

Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 137–38; Lecouteux, Les Nains et les Elfes au Moyen Âge; Motz, The Wise One of the Mountain; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1437–52; Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 107–11, 118–24, 147–48, 322.