N

NACHZEHRER: A particular kind of Germanic revenant. The name means “He Who Continues to Devour (after his death)” or “He Who Lures While Devouring.” The first account of a Nachzehrer comes from Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger, who were responsible for the suppression of witchcraft in the Rhineland during the last quarter of the fifteenth century.

An example was brought to our notice as Inquisitors. A town was once rendered almost destitute by the death of its citizens; and there was a rumor that a certain buried woman was gradually eating the shroud in which she had been buried, and that the plague could not cease until she had eaten the whole shroud and absorbed it into her stomach. A council was held, and the Podesta with the Governor of the city dug up the grave, and found half the shroud absorbed through the mouth and throat into the stomach and consumed. In horror at this sight, the Podesta drew his sword and cut off her head and threw it out of the grave, and at once the plague ceased. (Malleus Maleficarum, I, 15)

Martin Luther himself faced the problem posed by the belief in these wicked dead. A pastor named Georg Rörer wrote to him from Wittenberg that a woman living in a village had died and, after being buried, began eating herself in her grave; this caused all the inhabitants of this village to suddenly die (Table Talk, no. 6823). The Nachzehrer corresponds to the eighteenth-century French Mâcheur (from Latin manducator), the “Chewer.”

DRAUGR

DRAUGR

Lecouteux, The Secret History of Vampires, 70–75, 89, 91, 124, 131; Gerda Grober-Glück, “Der Verstorbene als Nachzehrer,” in Atlas der deutschen Volkskunde (Erläuterungen zu den Karten 43–48), 427–56; Günter Wiegelmann, “Der ‘lebende Leichnam’ im Volksbrauch,” Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 62 (1966): 161–83.

Lecouteux, The Secret History of Vampires, 70–75, 89, 91, 124, 131; Gerda Grober-Glück, “Der Verstorbene als Nachzehrer,” in Atlas der deutschen Volkskunde (Erläuterungen zu den Karten 43–48), 427–56; Günter Wiegelmann, “Der ‘lebende Leichnam’ im Volksbrauch,” Zeitschrift für Volkskunde 62 (1966): 161–83.

NAGLFAR (“Nail-ship”): This is the ship of the dead. It is made from the fingernails and toenails of the dead. This is why it is always necessary to trim the nails of the deceased before burying them, for if this is not done the nails will provide building material for the construction of Naglfar. The completion of the ship-building will be the sign that the end of the world has begun. The sons of Muspell will then travel on Naglfar to join the assault on Ásgarðr.

Hallvard Lie, “Naglfar og Naglfari,” Maal og Minne (1954): 152–61.

Hallvard Lie, “Naglfar og Naglfari,” Maal og Minne (1954): 152–61.

NÁGRINDR (“Corpse-fence”): Name of the metal gate that seals Hel, the underworld, and is also called Helgrindr (“Hel’s Fence”) and Valgrindr (“Fence of the Fallen”; the first element of the latter name is from valr, “the slain”).

NAL: The name of Loki’s mother according to Snorri Sturluson, whereas the Poetic Edda mentions only Laufey. The etymology of the name is uncertain: it could be related to Old Norse nál, which means “needle,” or it might possibly refer to death (nár means “corpse”).

NANNA: Wife of Baldr and daughter of Nepr, who is sometimes presented as Odin’s son. She is the mother of Forseti. She perishes from grief at Baldr’s death and is cremated with her husband. According to Snorri Sturluson, she is an Ásynja. Saxo Grammaticus calls Nanna the daughter of Gevarus, the king of Norway. She marries Hötherus (Höðr) but is loved by Balderus (Baldr), whom her husband kills.

NÁR (“Corpse”): The name of a dwarf; its meaning shows how closely these beings are connected to the dead.

NARFI: The son of Loki. In skaldic poetry Hel is referred to as “sister of the Wolf (Fenrir) and Narfi.” Narfi therefore appears to have a certain relationship with the realm of the dead, but we do not know what it is.

NÁSTRÖND (“Corpse-shore”): A place far from the sun where stands a hall whose door opens to the north. This hall is “woven with the spines of serpents,” with “poison drops falling through its roof,” says the Völuspá (The Prophecy of the Seeress) in the Poetic Edda. It is most likely one of the dwellings of Hel, the underworld, and its description was perhaps influenced by the Christian literature of revelations.

NECKLACE OF EARTH (Old Norse jarðarmen): When two people swear an oath of blood brotherhood (fóstbrœðralag) the ceremony, which is magical in nature, is accompanied by walking under a “necklace” (in fact, a strip) made of turf. According to the Fóstbrœðra saga (Saga of the Sworn Brothers), “It is necessary to cut three strips of sod with grass upon them and with both ends remaining set in the ground, which are then raised up in the form of arches so it is possible to pass beneath them.” Furthermore, the blood brothers must cut themselves so their blood can flow into and mix with the dirt. While doing this they swear their oath. It is possible that a magical relationship was thus established through an archaic form of worship of the Earth Mother and that this act was the equivalent of a journey into the maternal womb.

NEHALENNIA: A goddess whose name is known from third-century votive inscriptions. Temples to her existed at Domburg on the island of Walcheren and at Colijnsplaat (both in Zeeland, Netherlands). She is often depicted with a basket of fruit and is sometimes leaning on the prow or oar of a ship. In some cases she is accompanied by a dog. Nehalennia may correspond to the “Suebian Isis” mentioned by Tacitus and whose cultic image is in the form a ship. The dog’s presence in some images of Nehalennia could represent a connection with the otherworld, although the basket of fruit suggests that she is a guardian of fertility. We do know, however, that the dead can also play an important role in the latter domain.

Gutenbrunner, Die germanischen Götternamen der antiken Inschriften, 75–78.

Gutenbrunner, Die germanischen Götternamen der antiken Inschriften, 75–78.

NERTHUS: What we know about this goddess comes essentially from Tacitus, who reports of the Germanic peoples:

Collectively they worship Nerthus, or Mother Earth, and believe that she takes part in human affairs and rides among the peoples. On an island in the Ocean is a holy grove, and in it a consecrated wagon covered with hangings; to one priest alone is it permitted so much as to touch it. He perceives when the goddess is present in her innermost recess, and with great reverence escorts her as she is drawn along by heifers. Then there are days of rejoicing, and holidays are held whenever she deigns to go and be entertained. They do not begin wars, they do not take up arms; everything iron is shut away; peace and tranquility are only then known and only then loved, until again the priest restores to her temple the goddess, sated with the company of mortals. Then the wagon and hangings and, if you will, the goddess herself are washed clean in a hidden lake. Slaves perform this service, and the lake at once engulfs them. (Germania, chap. 40, trans. Rives)

The name of this mother goddess corresponds linguistically to that of the male Norse god Njörðr, and both names can be assumed to derive from an earlier proto-Germanic form, *Nerthuz. The shift that seems to have occurred here from a goddess to a god has been explained as either a division of a Freyr-Freyja kind, or as a result of the deity’s original hermaphroditic nature. In Zealand, Denmark, where the worship of Nerthus would have taken place, there is a place named Niartharum (present-day Nærum), in which the name of Nerthus/Njörðr can be recognized. The son of Nerthus is Tuisto, which means “double, twofold,” in other words, a hermaphrodite like the giant Ymir. It should be recalled that the ancient Germanic deities were often androgynous, a feature for which we can find substantial traces. The most striking examples of this tendency are the numerous pairs of corresponding male and female deities such as the one described here (Nerthus-Njörðr), or the various female deities with male names.

NEUNTÖTER (“Nonicide”): Dead who are predestined to come back because, at birth, they have teeth or a double row of teeth. They die young and cause the death of nine of their close relatives (hence the name, which literally means “Nine-killer”). It was believed that the Neuntöter attracted those to itself whom it had liked most, or else that some unfortunate circumstance had occurred at his or her death: a cat had been allowed to walk over the corpse; the eyes of the deceased had refused to close; the scarf of a woman laying out the body had brushed the lips of the corpse; and so forth. The Neuntöter was also said to spread plague. The preferred method for getting rid of a Neuntöter was decapitation.

Lecouteux, The Secret History of Vampires, 64–66, 89.

Lecouteux, The Secret History of Vampires, 64–66, 89.

NEUTRAL ANGELS: The clerics of the Middle Ages often explained the origins of demons and spirits, under whatever name (giants, dwarves, elves, and so on), by the legend of the neutral angels. When Lucifer rebelled against God, some timorous or hesitant angels did not choose to stand with either side. God therefore cast them down to Earth, while Lucifer was consigned to live in hell. Some of these angels fell into the forests, some into the water, and others remained in the air; it is from them that elves, fairies, and similar beings originate. In Ireland it is believed that fairies were members of this group of angels condemned to remain on Earth.

Marcel Dando, “The Neutral Angels,” Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen und Literaturen 217 (1980): 259–76; Bruno Nardi, “Gli angeli che non furon ribelli né fur fedeli a Dio,” in Nardi, Dal ‘Convivio’ alla ‘Commedia’: Sei Saggi Danteschi (Rome: Instituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1960), 331–50.

Marcel Dando, “The Neutral Angels,” Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen und Literaturen 217 (1980): 259–76; Bruno Nardi, “Gli angeli che non furon ribelli né fur fedeli a Dio,” in Nardi, Dal ‘Convivio’ alla ‘Commedia’: Sei Saggi Danteschi (Rome: Instituto Storico Italiano per il Medio Evo, 1960), 331–50.

NIBELUNGENLIED (Lay of the Nibelungs): Written at the start of the thirteenth century but drawing on older sources, the Nibelungenlied consists of two parts: the legend of Siegfried and the story of Kriemhild’s vengeance. An outline of the Nibelungenlied goes as follows: Siegfried is the son of King Sigemund and Sigelinde, who live in xanten. He goes to the Burgundian court in Worms because he wishes to wed King Gunther’s sister Kriemhild. When Siegfried introduces himself, the anonymous author of the saga gives a brief overview of his mythic exploits: he slew a dragon and bathed in its blood, which made him invulnerable except between his shoulders, where the leaf of a linden tree had fallen; he slew the kings Schilbung and Nibelung and took their treasure after defeating their vassal, the dwarf Alberich (from whom he took the Tarnkappe, the “cloak of invisibility”) and their allies, twelve strong giants. Siegfried helps Gunther win Brünhild’s hand in return for his promise to let him wed Kriemhild. Using the cloak of invisibility, he procures Gunther’s victory over Brünhild in the contests that the lady imposes on all her suitors. (If the suitor is defeated, he must surrender his life!) After returning to Worms, Gunther weds Brünhild and Siegfried weds Kriemhild. When Gunther is unable to subdue his bride in their nuptial bed, he turns to his brother-in-law, who, invisible and unrecognizable, takes his place in bed, subdues Brünhild, and takes her belt and ring, which he then gives to his own wife. In the course of a quar-rel between the two women over status, Kriemhild reveals to Brünhild what happened on her wedding night and shows her the stolen objects. This triggers an act of vengeance from Brünhild. The deed is carried out by Hagen, who stabs Siegfried with his spear near a spring in the Odenwald. Hagen seizes Siegfried’s treasure and casts it into the Rhine to prevent Kriemhild from having the necessary means to get revenge.

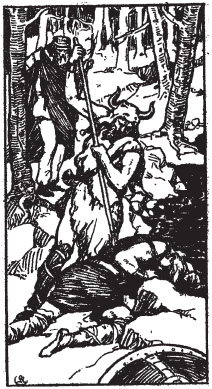

Fig. 60. Hagen kills Siegfried. Illustration from a German textbook, Paris, 1926.

King Etzel (Attila) requests and obtains the hand of the Burgundian king’s widowed sister in marriage. Kriemhild moves to Etzelburg, where she lives at his side and has two sons. She invites her brothers to visit, and they accept despite the warnings of Hagen, who has guessed Kriemhild’s true motive. Traveling to Etzelburg, they meet sirens on the banks of the Danube, and Hagen sees his intuition confirmed: the Burgundians will die during this journey. At Etzelburg they are all slaughtered, except for Gunther and Hagen, who are taken prisoner. Kriemhild has her brother decapitated because Hagen refuses to tell her where he sank the treasure for as long as Gunther lives. Taking Gunther’s head by the hair, Kriemhild presents it to Hagen, who says, “No one shall know now where the treasure is, outside of God and me!” Kriemhild then draws Siegfried’s sword, Balmung, from its scabbard and lops off Hagen’s head, but she perishes immediately afterward when she is cut down by Hildebrand, the armorer of Dietrich von Bern.

SIEGFRIED

SIEGFRIED

Colleville and Tonnelat, trans., La Chanson des Nibelungen; Hatto, trans., The Nibelungenlied; Lecouteux, La Légende de Siegfried d’après le Seyfrid à la peau de corne et la Thidrekssaga; Lecouteux, “Stratigraphische Untersuchungen zur Siegfriedsage,” in Sagen- und Märchenmotive im Nibelungenlied, ed. Gerald Bönnen and Volker Gallé (Worms: Stadtarchiv Worms, 2002), 45–69; Lecouteux, “Der Nibelungenhort: Überlegungen zum mythischen Hintergrund,” Euphorion 87 (1993): 172–86; Lecouteux, “Seyfrid, Kuperan et le dragon,” Études Germaniques 49 (1994): 257–66.

Colleville and Tonnelat, trans., La Chanson des Nibelungen; Hatto, trans., The Nibelungenlied; Lecouteux, La Légende de Siegfried d’après le Seyfrid à la peau de corne et la Thidrekssaga; Lecouteux, “Stratigraphische Untersuchungen zur Siegfriedsage,” in Sagen- und Märchenmotive im Nibelungenlied, ed. Gerald Bönnen and Volker Gallé (Worms: Stadtarchiv Worms, 2002), 45–69; Lecouteux, “Der Nibelungenhort: Überlegungen zum mythischen Hintergrund,” Euphorion 87 (1993): 172–86; Lecouteux, “Seyfrid, Kuperan et le dragon,” Études Germaniques 49 (1994): 257–66.

NIÐAFJÖLL (“Mountain of Darkness”): The mountain in the underworld that is the native home of the dragon Niðhöggr. According to Snorri Sturluson, this is the location of Sindri, a hall made of pure gold where the good and virtuous live after Ragnarök.

NIÐAVELLIR (“Dark Plains”): A site located in the north, where stands the hall of the dwarves of Sindri’s race. Ordinarily dwarves live underground, in the stones and mountains.

NÍÐHÖGGR (“He Who Delivers Hateful Blows” or possibly “He Who Strikes from Darkness”): A dragon native to Niðafjöll who lives in the kingdom of the dead. On Náströnd he sucks on the corpses of the dead. He too will live on in the renewed world following Ragnarök. One tradition says that he dwells beneath the cosmic ash, Yggdrasill, and gnaws at its roots.

NIFLHEIMR (“World of Darkness”): A northern area that existed long before the creation of the world. This is the location of the spring Hvergelmir, which is the source of ten rivers. It is possible that Niflheimr is identical to Nifhel and would thus be one of the names of Hel.

NIFLHEL (“The Dark Hel”): This is one part of Hel; it is the ninth domain and the deepest of them all. This notion, most likely related to shamanic perceptions of the beyond, may also have been influenced by visionary literature: in the Christian descriptions of hell there is always an abyss, such as in The Visions of the Knight Tondal.

NIGHTMARE:  MAHR

MAHR

NISS: A place spirit similar to a dwarf that is often malicious and even sometimes malevolent. When it is friendly it is called a Goaniss (Sweden). One legend claims it is a fallen angel. In Norway it is the size of a five- or six-year-old child and has only four fingers on each hand (it has no thumbs). Its hands are also hairy.

Fig. 61. Niss, from a Norwegian Christmas card

In Sweden it is an old bearded man wearing a red cap and gray clothing. Offerings of food are given to it and placed in the farmyard beneath a stone that is assumed to be its dwelling or at the foot of a tree. It is sometimes confused for another household spirit, the Puk or Puge.

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 165–69; Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 155–62; Keightley, The World Guide to Gnomes, Fairies, Elves, and Other Little People, 139–47; Hans F. Feilberg, “Der Kobold in nordischer Überlieferung,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 8 (1898): 1–20, 130–46, 264–77; Ottar Grønvik, “Nissen,” Maal og Minne (1997): 129–48; Oddrun Grønvik, “Ordet nisse o.a. i dei nynorske ordsamlingane,” Maal og Minne (1997): 149–56.

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 165–69; Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 155–62; Keightley, The World Guide to Gnomes, Fairies, Elves, and Other Little People, 139–47; Hans F. Feilberg, “Der Kobold in nordischer Überlieferung,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 8 (1898): 1–20, 130–46, 264–77; Ottar Grønvik, “Nissen,” Maal og Minne (1997): 129–48; Oddrun Grønvik, “Ordet nisse o.a. i dei nynorske ordsamlingane,” Maal og Minne (1997): 149–56.

NISSPUCK: The name for the Niss in Schleswig-Holstein.

Erika Lindig, Hausgeister, 78ff.

Erika Lindig, Hausgeister, 78ff.

NIX(E):  FOSSEGRIM, NYKR, WASSERMANN

FOSSEGRIM, NYKR, WASSERMANN

NJÖRÐR: Vanir god, the father of Freyr and Freyja and a medieval reflex of the goddess Nerthus. He married the giantess Skaði, the eponymous goddess of the Scandinavian lands. Snorri Sturluson tells us: “Njörðr lives in Noatún [“Ship-enclosure”]. He rules over the motion of wind and moderates sea and fire. It is to him one must pray for voyages and fishing. He is so rich and wealthy that he can grant wealth of lands or possessions to those that pray to him for this” (Gylfaginning, trans. Faulkes). He was raised among the Vanir, who later traded him as a hostage to the Æsir in exchange for Hœnir.

The union of a maritime god with an Earth-based goddess resulted in a famous myth. Njörðr could not tolerate the mountains and their snow, while Skaði could not sleep by the sea because of the noise of the waves and the cries of the gulls. They then decided to divide their time between both residences, alternating nine days on the coast followed by nine days in the mountains, but this was not enough to prevent their separation.

Njörðr is regularly invoked in oaths along with Freyr and the “allmáttki áss” (the “almighty god,” Odin). Sacrifices should be made to him at the same time as Odin and Freyr to ensure a peaceful and fruitful year. Njörðr has left substantial traces in Scandinavian place-names, for example that of Narvik, Norway, which can be assumed to derive from an earlier form, Njarðarvík, meaning “Njörðr’s Bay.”

Dumézil, From Myth to Fiction: The Saga of Hadingus, 20–22, 225–27.

Dumézil, From Myth to Fiction: The Saga of Hadingus, 20–22, 225–27.

NOATÚN (“Ship-enclosure”): Njörðr’s place of residence.

NORÐRI (“North”): One of the four dwarves that hold up the heavenly vault at the four cardinal points; this vault was created from the skull of the giant Ymir. One kenning calls the sky the “burden of Norðri’s relatives,” and this dwarf ’s name appears in Óláfsdrápa (strophe 26).

Lecouteux, “Trois hypothèses sur nos voisins invisibles,” in Hugur: mélanges d’histoire, de littérature et de mythologie offerts à Régis Boyer pour son 65e anniversaire, ed. Lecouteux and Gouchet, 289–92.

Lecouteux, “Trois hypothèses sur nos voisins invisibles,” in Hugur: mélanges d’histoire, de littérature et de mythologie offerts à Régis Boyer pour son 65e anniversaire, ed. Lecouteux and Gouchet, 289–92.

AUSTRI, COSMOGONY, SUÐRI, VESTRI

AUSTRI, COSMOGONY, SUÐRI, VESTRI

NORGEN, NÖRGL, NÖRGLEIN, NÖRGGELEN (neut., sg. and pl., “grumpy one[s]”): In Tyrolean belief, these are fallen angels that became place spirits. When they were driven out of heaven not all of them reached hell. During their fall, many of those who had gone along with the rebels, but who did not share their wicked nature, remained clinging to the trees and mountains. They still live in trees and in hollows, and they must remain on Earth until the day of Final Judgment. Many people claim that the Nörglein are sneaky because they made common cause with Lucifer and envied humanity’s good fortune.

Zingerle, Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Tirol, no. 83.

Zingerle, Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Tirol, no. 83.

NÖRGL (masc.), NÖRGIN (fem.): A merman and mermaid of the Tyrolean lakes.

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 54; Zingerle, Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Tirol, nos. 81–84, 98, 105, 127.

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 54; Zingerle, Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Tirol, nos. 81–84, 98, 105, 127.

NORNS: The goddesses of fate who almost always appear as a group of three figures. About them, Snorri Sturluson writes: “A beautiful hall stands under the ash by the well [i.e., beneath Yggdrasill], and out of this hall come three maidens whose names are Urðr [“Past”], Verðandi [“Present”], and Skuld [“Future”]. They shape the lives of men. We call them Norns” (Gylfaginning).

These maidens are giantesses who sprinkle clear water and white clay on the tree every day. They are depicted as wicked and ugly; their verdict is irrevocable. It is said they come from the sea. Snorri goes on to remark: “There are also other Norns who visit everyone when they are born to shape their lives, and these are of divine origin, though others are of the race of elves, and a third group are of the race of dwarves” (Gylfaginning, trans. Faulkes).

Fig. 62. The three Norns at the foot of Yggdrasill. Drawing by Arthur Rackham (1867–1939).

The Norns correspond to the Fates—the Greek Moirai and the Roman Parcae—as well as to the fairies of Celtic and Roman legends. In fact, several texts in Old French depict three fairies around a cradle who endow a child with beneficial or harmful aspects, a theme also found in the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty. Only the Norn Urðr appears to be ancient and authentic (the Old Norse name is cognate to wurt in Old High German and wurd in Old Saxon); Skuld and Verðandi appear to be later additions to form a triad modeled on the Parcae. Furthermore, the spring at the foot of Yggdrasill is named the “Well of Urðr” (Urðarbrunnr).

Bek-Pedersen, The Norns in Old Norse Mythology.

Bek-Pedersen, The Norns in Old Norse Mythology.

NÖRR (“Narrow”): Name of the father of Nótt (“Night”).

NÓTT (“Night”): The personification of night. This is how the texts describe her:

Nörfi or Narfi was the name of a giant who lived in Jötunheimr. He had a daughter called Night [Nótt]. She was black and dark in accordance with her ancestry. She was married to a person called Naglfari with whom she had a son, Auðr. Next she was married to someone called Annar. Their daughter was called Jörð [Earth]. Her last husband was Delling, he was of the race of the Æsir. Their son was Day [Dagr]. He was bright and beautiful in accordance with his father’s nature. Then All-father [Alföðr = Odin] took Night and her son Day and gave them two horses and two chariots and set them up in the sky so that they have to ride around the earth every twenty-four hours. Night rides in front with a horse named Hrímfaxi, and every morning he bedews the earth with the drips from his bit. Day’s horse is called Skinfaxi, and light is shed all over the sky and sea from his mane. (Snorri Sturluson, Gylfaginning, trans. based on Faulkes)

NYBLINC: In a fifteenth-century poem, Das Lied vom hürnen Seyfrid (The Lay of Horn-skinned Siegfried), Nyblinc is a dwarf introduced as the owner of a treasure stolen by Seyfrid. He therefore corresponds to Nibelung of the Nibelungenlied.

Lecouteux, La Légende de Siegfried d’après le Seyfrid à la peau de corne et la Thidrekssaga.

Lecouteux, La Légende de Siegfried d’après le Seyfrid à la peau de corne et la Thidrekssaga.

NYKR (Old Norse, pl. nykar; Old English nicor): Mythical animal and water spirit that has an etymological connection to the German Nix(e). It was originally capable of assuming a thousand different forms (in Old High German nihhus even means “crocodile”). In Scandinavia a nykr can sometimes take the shape of a dapple-gray horse, a color indicative of its supernatural origin. It is called a “horse of the lakes” (vatnahestur) in Icelandic folklore. It is also said to be able to take a human form. In Norway it is called nøkk; in Denmark, nøkke; and in Sweden, näck. In Norway we also find the names fossekall and fossegrim (“waterfall-spirit”) and kvernknurre (“watermill-spirit”). In the Shetlands the nykr becomes the njuggel; it is depicted as a horse with a wheel for a tail. It lurks near lochs and waterways. It hides its tail and adopts a tame disposition when it invites the weary traveler to climb on its back. But once the unfortunate victim is in the saddle, it flies away like lightning, with its tail in the air and its mane streaming, to the nearest loch to drown him. The only way the poor rider can save himself is to speak its name, for it will then lose its power. The njuggel also stops the wheel of watermills if no one offers it grain or flour. To chase it away, people then light a fire.

FOSSEGRIM, MERMAID/MERMAN, UNDINE, WASSERMANN

FOSSEGRIM, MERMAID/MERMAN, UNDINE, WASSERMANN

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 101–4; Grambo, Svart katt over veien, 117 (nøkken); Keightley, The World Guide to Gnomes, Fairies, Elves, and Other Little People, 147–55, 258–63; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1425–36; Brita Egardt, “De svenska vattenhästsägnerna och deras ursprung,” Folkkultur 4 (1944), 119–66; Hans F. Feilberg, “Der Kobold in nordischer Überlieferung,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 8 (1898): 1–20, 130–46, 264–77; Lecouteux, “Nicchus–Nix,” Euphorion 78 (1984): 280–88.

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 101–4; Grambo, Svart katt over veien, 117 (nøkken); Keightley, The World Guide to Gnomes, Fairies, Elves, and Other Little People, 147–55, 258–63; Van den Berg, De volkssage in de provincie Antwerpen in de 19de en 20ste eeuw, 1425–36; Brita Egardt, “De svenska vattenhästsägnerna och deras ursprung,” Folkkultur 4 (1944), 119–66; Hans F. Feilberg, “Der Kobold in nordischer Überlieferung,” Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 8 (1898): 1–20, 130–46, 264–77; Lecouteux, “Nicchus–Nix,” Euphorion 78 (1984): 280–88.