O

OAK: Oak trees were particularly worshipped in Prussia, where they were believed to house the gods Perkunos (Thunder), Pikollos (Death), and Potrimps (War and Fertility). The Romove Oak in Nadruvia was six ells in thickness and remained green in winter and summer. Gilded curtains that were eight ells high surrounded it. They were only opened on feast days or when a Prussian noble visited to make a rich sacrifice. Another renowned sacred oak was that of Heiligenbeil; it shared the same characteristics as the Romove tree but housed Gorcho, the god of food and drink. Bishop Anselm cut it down. There was also the oak of Geismar, chopped down by Saint Boniface.

Schütz, Historia rerum Prussicarum, 4; Simon Grunau, Preussische Chronik, vol. II, 5.

Schütz, Historia rerum Prussicarum, 4; Simon Grunau, Preussische Chronik, vol. II, 5.

ÓDÁINSAKR (“Deathless Field”): A paradisiacal place mentioned in the later genre of legendary sagas known as fornaldarsögur (sagas of ancient times). It can be compared with various names for the Celtic afterlife that reflect the same notion of the survival of heroes in the otherworld.

ODIN (Old Norse Óðinn; Old English Woden; Old Saxon Wodan; Old High German Wuotan): The principal deity of the Norse and Germanic pantheon is a cruel and spiteful god, a cynical and misogynistic double-dealer whom the Romans interpreted as being similar to Mercury. He is one-eyed because he offered one of his eyes as a pledge to the giant Mímir in return for access to knowledge. He is old and graying, with a long beard, and has a hat pulled low over his brow. He wears a blue cloak. Etymologically his name means “Fury,” as was noted by Adam of Bremen (“Wodan id est furor”) in his eleventh-century chronicle, History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen.

Odin is the son of the giant Burr (who is the son of Búri and Bestla, Bölþorn’s daughter), and he has two brothers, Vili and Vé. Together Odin and his brothers slay the primordial giant Ymir, whose body becomes the world. Odin’s wife is Frigg, with whom he had a son, Baldr. Thor was born as a result of Odin’s relations with the giantess Jörð, and another son, Váli, came from his liason with the giantess Rindr. In Ásgarðr, Odin lives in Valhöll (Valhalla), seated on his throne, Hliðskjálf, from which he can see the entire world. His attributes are the spear Gungnir, which he casts over the combatants before a battle begins in order to determine who will be victorious; his ring, Draupnir, from which drip eight other similar rings every ninth night; and his horse, Sleipnir, which has eight legs. According to Snorri Sturluson, he also owns the wondrous boat Skíðblaðnir, although this object is usually attributed to Freyr.

Fig. 63. Odin in all his majesty. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

Odin is a psychopomp like Mercury as well as a necromancer. He is called “Lord of the Revenants” and “God of the Hanged Men.” He enchanted the severed head of the giant Mímir and regularly consults with it. He is master of the “Hall of the Slain” (Valhöll), where he lives exclusively on wine and gives all his food to the wolves Geri and Freki. The dead men he has selected through his intermediaries, the valkyries, are his fellow inhabitants of Valhalla and are called einherjar, the “elite, single warriors.” He owns two ravens, Huginn and Muninn (“Thought” and “Memory”), who fly out each day and return to report all the news of the world to him, for he has given them the power of speech.

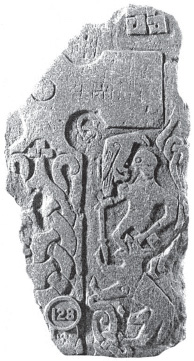

Fig. 64. Odin devoured by the wolf Fenrir. Thorwald’s Cross (tenth to eleventh century), Kirk Andreas, Isle of Man.

Odin is omniscient and knows runes, magic, and poetry. He likes to test his learning against that of the giants ( VAFÞRÚÐNIR) and has the power of rendering his foes blind, deaf, and paralyzed (

VAFÞRÚÐNIR) and has the power of rendering his foes blind, deaf, and paralyzed ( HERFJÖTURR). He can stop arrows in flight, and he can make his supporters invulnerable.

HERFJÖTURR). He can stop arrows in flight, and he can make his supporters invulnerable.

He resuscitates the hanged and other dead men and is the leader of the Wild Hunt (Wodans Jagd, Wuotes her) in all Germanic countries.

Odin is adept in the magical technique known as seiðr ( SEIÐR), and he is the master of poetry because he drank the magical mead brewed from the blood of Kvasir. He is also a kind of god-shaman, and his entire character is evidence of the survival of a substantial substratum of shamanistic beliefs. He acquired his powers through a nine-night initiation during which he hung upside down from a wind-battered tree. As as result of this he is both a seer and a sorcerer. He can become cataleptic or enter into trance to allow his Double (alter ego) to fare forth and travel the world in the guise of an animal while his body remains lifeless.

SEIÐR), and he is the master of poetry because he drank the magical mead brewed from the blood of Kvasir. He is also a kind of god-shaman, and his entire character is evidence of the survival of a substantial substratum of shamanistic beliefs. He acquired his powers through a nine-night initiation during which he hung upside down from a wind-battered tree. As as result of this he is both a seer and a sorcerer. He can become cataleptic or enter into trance to allow his Double (alter ego) to fare forth and travel the world in the guise of an animal while his body remains lifeless.

In the euhemeristic interpretation of Snorri Sturluson’s Ynglinga saga, Odin is an Asiatic king ruling over Ásgarðr, which is located east of the Don River. One time while Odin was away traveling, his two brothers shared his inheritance between them, including his wife, but he took everything back when he returned. He warred against the Vanir. Due to his gift of prophecy, he knew that his descendants would settle in the north. He therefore gave Ásgarðr back to his brothers, Vili and Vé, and set off northward, eventually reaching the sea where he settled first on the island of Odinsey (Odense) and then on the shores of lake Løgrinn (today called Mälaren) in Sigtuna (Signhildsborg, Sweden).

A vast number of theophoric place-names provide evidence for both Odin’s importance and his antiquity. The literary texts have also preserved more than 170 names and titles of Odin that are reflective of his deeds and his personality ( GÖNDLIR). His name is also evident in the weekday name Wednesday (which derives from Old English wodnesdæg, “Woden’s Day”).

GÖNDLIR). His name is also evident in the weekday name Wednesday (which derives from Old English wodnesdæg, “Woden’s Day”).

Fig. 65. Odin mounted on Sleipnir. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

In terms of his structural function in the mythology, Odin corresponds to the Mithra-Varuna pair of the Indo-Aryans and to the Roman Jupiter.

WODAN, WODEN

WODAN, WODEN

Kershaw, The One-eyed God; Régis Boyer, “Óðinn d’après Saxo Grammaticus et les sources norroises: étude comparative,” Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie 15 (1986): 143–57; Peter Buchholz, “Odin: Celtic and Siberian Affinities of a Germanic Deity,” Mankind Quarterly 24:4 (1984): 427–37; Lotte Motz, “Óðinn’s Vision,” Maal og Minne 1 (1998): 11–19; Clive Tolley, “Sources for Snorri’s Depiction of Óðinn in Ynglinga Saga: Lappish Shamanism and the Historia Norvegiae,” Maal og Minne 1 (1996): 67–79.

Kershaw, The One-eyed God; Régis Boyer, “Óðinn d’après Saxo Grammaticus et les sources norroises: étude comparative,” Beiträge zur nordischen Philologie 15 (1986): 143–57; Peter Buchholz, “Odin: Celtic and Siberian Affinities of a Germanic Deity,” Mankind Quarterly 24:4 (1984): 427–37; Lotte Motz, “Óðinn’s Vision,” Maal og Minne 1 (1998): 11–19; Clive Tolley, “Sources for Snorri’s Depiction of Óðinn in Ynglinga Saga: Lappish Shamanism and the Historia Norvegiae,” Maal og Minne 1 (1996): 67–79.

ÓÐR (“Fury,” “Magical Inspiration”): Husband of Freyja, with whom he had a daughter, Hnoss (“Jewel”), also called Gersimi (“Treasure”). He went away on long journeys, and Freyja wept tears of red gold. The close kinship of the names Óðr and Óðinn, along with the parallel nature of the Óðr-Freyja and Óðinn-Frigg couples and also the fact that Freyja and Odin share the dead warriors between them, shows that a very close bond exists between these four figures.

OÐRŒRIR: One of the containers used by the dwarves Fjalarr and Galarr to collect the blood of Kvasir.

ÖLNIR: Name of a dwarf presented as Odin’s son.

ÖLRUN: The name of a valkyrie and the daughter of King Kiarr of Valland. She is described as a swan maiden and is the sister of Hervör alvitr and Hlaðguðr svanhvít. These three sisters marry Völundr (Wayland) and his brothers. Her name is interesting: öl could mean “ale,” in which case Ölrun would mean “Ale-secret,” and this in turn may refer to Freyr’s sphere of activity ( ByGGVIR). But öl might also derive from the root *alb-, meaning “elf ” (with the etymological sense of a “white, ghostly being”); in this case, the name Ölrun would be identical to that of Albruna, the name of a Germanic seeress mentioned by Tacitus, and both would have the meaning of “Elf-secret” or “Secret of the White Being.”

ByGGVIR). But öl might also derive from the root *alb-, meaning “elf ” (with the etymological sense of a “white, ghostly being”); in this case, the name Ölrun would be identical to that of Albruna, the name of a Germanic seeress mentioned by Tacitus, and both would have the meaning of “Elf-secret” or “Secret of the White Being.”

HERVÖR ALVITR, HLAÐGUÐR SVANHVÍT, SWAN MAIDEN, VALKYRIE, WAYLAND THE SMITH

HERVÖR ALVITR, HLAÐGUÐR SVANHVÍT, SWAN MAIDEN, VALKYRIE, WAYLAND THE SMITH

ÖLVALDI (“Beer Master”): A giant who was father to Þjazi, Iði, and Gangr. When he divided up his property among them, each of them was allowed to take only a mouthful of gold, which is why gold is called “Þjazi’s (or Iði’s or Gangr’s) mouthful” in skaldic poetry.

ÖNDVEGISSÚLUR: The “support posts of the high seat,” meaning the seat of honor for the head of the household. These were sculpted, carved, or painted, most likely with the image of a god or goddess. When the early Norse settlers left Norway and sailed to Iceland to colonize the island, they brought their high-seat posts with them. As they came within sight of land they threw the posts overboard with the stated intention of seeing where the guardian spirit would take them. They would settle in the place where the post washed ashore.

ORDEAL (Norwegian ordal; German Urteil, “Judgment”): In northern Germanic legal custom, the most common form of the ordeal is that of “iron-bearing” (járnburðr). In this procedure the defendant had to bear a piece of red-hot iron for some nine paces, namely to carry it up to a cauldron. In a variant version the defendant had to walk across twelve red-hot plowshares. Another ordeal consisted of retrieving an object the size of an egg with one’s bare hands from a cauldron of boiling water. If the ordeal was successfully accomplished before the official witnesses, this was taken as evidentiary proof of the defendant’s innocence or truthfulness.

ORG (pl. Orgen): The Orgen are woodland dwarves of the Tyrol who only go out at night. They are the size of a cat. If one is touched it feels like a sack of flour. They will slip into solitary houses but only those close to the forest. Their favorite activity is chopping wood. In the Val Passiria (South Tyrol), an Org measures one span and resembles a cat. It leaps on passersby and forces them to carry him.

Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 84–86, 209.

Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 84–86, 209.

ÖRHHELER:  NORGEN

NORGEN

ORK, ORG, NORG, LORKO, ORCO: A demon of the Tyrolean Alps whose name means “ogre.” The traditions are highly varied: sometimes it is solitary and sometimes it lives in a group; in can be gigantic or it can be a dwarf. It is the Master of Animals. Starting around 1250 it turns up in adventure tales where it is named “Orkise” or “Wunderer.”

WUNDERER

WUNDERER

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 72–75; Insam, Der Ork; Petzold, Kleines Lexikon der Dämonen und Elementargeister, 138–39.

Alpenburg, Mythen und Sagen Tirols, 72–75; Insam, Der Ork; Petzold, Kleines Lexikon der Dämonen und Elementargeister, 138–39.

ÓSKMEY, ÓSKMÆR: Synonymous term for a valkyrie. The word is a combination of ósk, “wish,” and maer, “maiden.” These individuals would therefore be “the maidens who grant the wishes” of Odin and/or of warriors.

VALKYRIE

VALKYRIE

OSKOREIA (“The Terrifying Ride”): One of the names in Norway for the Wild Hunt. It either involves a troop of masked men or else spirits traveling by horseback (ridende julevetter, “riding Yule-wights”) between Christmas and Epiphany or on the feast of Santa Lucia (whose name also underlies another designation for the Wild Hunt: Lussiferdi) on December 13. In Scandinavia the cycle of the Twelve Days (also known in German as the Rauhnächte or Rauchnächte, a cycle of twelve nights) can run from December 13 to Christmas, or from Christmas to January 6.

Other names for the Wild Hunt in Norway include the Julereia, Trettenreia, Fossareia, and Imridn, all of which contain the word rei, reid, “to ride as a company on horseback,” sometimes grafted to the determiner Jul/Jol (“Christmas”) or Imbre/Imbredagene, terms designating the four days of Lent of the liturgical year (ieiunia quatuor), or Fosse (the name of a spirit). Trettenreia or Trettandreia refers to “the troop of riders of the thirteenth day [of winter].”

The troop travels through the sky or parades in a file over land and is characterized by two essential motifs: a bond with horses and a connection to food and drink. The first motif recalls the comments by thirteenth-century authors that, during the period of Twelve Days, spirits slip into the stables and make off with the horses, returning them later covered with sweat as if they had been galloping great distances. It was said by the common people that the members of the Oskoreia or Lucia had ridden them (at merri var Lussi-ridi). The second motif is the theft of food and drink—especially drink. The “Oskoreians” sneak into the houses and cellars, steal the food, and empty the casks of their beer and replace it with water.

Edvardsen, Gammelt nytt i våre tidligste ukeblader, 79–124 (texts); Lecouteux,

Phantom Armies of the Night; Walter, ed., Le Mythe de la Chasse sauvage dans l’Europe mediévale; Christine N. F. Eike, “Oskoreia og ekstaseriter,” Norveg 23 (1980): 227–309, maps at 242 and 247.

Edvardsen, Gammelt nytt i våre tidligste ukeblader, 79–124 (texts); Lecouteux,

Phantom Armies of the Night; Walter, ed., Le Mythe de la Chasse sauvage dans l’Europe mediévale; Christine N. F. Eike, “Oskoreia og ekstaseriter,” Norveg 23 (1980): 227–309, maps at 242 and 247.

OSTARA (Old English Eastre): This may be the name of an ancient goddess of spring. The Venerable Bede (673–735) designates the month of April as Eastermonaþ. Eastre can be seen underlying the name of the festival of Easter.

Shaw, Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World, 49–71.

Shaw, Pagan Goddesses in the Early Germanic World, 49–71.

OURK: Name of the Wild Huntsman in Floruz, in the Gadler parish of the Tyrol. There is an odd twist to the hunting motif in this local legend; it features the strange atonement of the man who demanded—and received—the hand of a dead man. The guilty party has to wear a copper kettle on his head, take a cat under his arm, hold a rosary in his hand, and then utter this appeal: “Wild Huntsman, come back quick and take this prey, it is of no use to me!”

Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 2–3.

Zingerle, Sagen aus Tirol, 2–3.