R

RÅ: This word designates a supernatural being in Sweden that lives in certain places and rules over them (as in the verb råda, “to rule”). In the water there is the sjörå; in the mountains, the bergrå; in the forest, the skogsrå; in the house, the husrå or gardsrå; in the stable, the stallrå; in the church, the kirkrå, who is often the first person buried on this site; and in the mines, the gruvrå. When building on a site, a human being or sow would be sacrificed to the rå. The rå is also the Master of Animals, and sometimes he has buried treasure in his keeping. He occasionally assumes the appearance of a seductive woman with a foxtail and a back that is hollow like a kneading trough. This final detail is found in German charms against elves.

The Swedish also use the term rådande, the male or neuter present participle of råda, to designate the rå.

Granberg, Skogsrået i yngre nordisk folktradition, 205–9; Hultkrantz, ed., The Supernatural Owners of Nature.

Granberg, Skogsrået i yngre nordisk folktradition, 205–9; Hultkrantz, ed., The Supernatural Owners of Nature.

RAGNARÖK (“Judgment of the Ruling Powers [= Gods]”): The name for the Norse apocalypse, the end of the world, which was later popularized by Wagner as the Götterdämmerung, “Twilight of the Gods.” The catastrophic scenario takes place as follows. Three dreadful winters follow each other in succession. Hel’s three roosters—Fjalarr, Gullinkambi, and the “soot-red rooster”—crow in a dire manner as Fenrir (or Garmr) shakes his chains. He breaks them, swallowing the sun and moon. Yggdrasill trembles, the Earth convulses, the Midgard Serpent writhes up out of the sea and causes widespread flooding. The giants leave their land on the boat Naglfar, and one of them, Surtr, throws himself into the assault of Valhalla by way of the rainbow bridge. Odin is slain by Fenrir, who is then slain by Víðarr. Freyr falls to Surtr, and Thor and the Midgard Serpent slay each other. The same is true for Týr and Garmr, and Loki and Heimdallr. Surtr then sets the entire world ablaze.

The Earth then emerges from the waves, beautiful and green. Viðarr and Váli live in Iðavöllr, on the site where Ásgarðr once stood. They are joined there by Thor’s sons, Móði and Magni, who bring Mjöllnir with them. Baldr and Höðr return from Hel’s domain. Two humans survive named Líf and Lífþrasir; they remained hidden and were spared by Surtr’s fire. They will repopulate the Earth. The sun reappears because Sól had given birth to a daughter just as beautiful as she was before she perished.

Martin, Ragnarök.

Martin, Ragnarök.

RÁN (“Robbery”): Goddess of the sea, the wife of Ægir, and mother of the waves. She owns a net that she uses to capture all the men who fall into the sea. In the realm of the dead beneath the sea, she rules over all of the sailors who died on the waters.

RATATOSKR (“Rat-tooth”): Name of the squirrel who nests in the branches of the cosmic tree, Yggdrasill. He climbs up and down constantly, bringing the words of the eagle perched in its highest branches down to Níðhöggr at its base, and vice versa.

RATI (“Borer”): Name of the drill used by the giant Baugi to pierce a hole in the side of Hnitbjörg Mountain where Gunnlöð keeps watch over the wondrous mead made from Kvasir’s blood.

Fig. 68. Baugi bores into the mountain with Rati to gain possession of the wondrous mead. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

RAUE ELSE (“Wild Else”): Wild woman and water nymph in the legends surrounding Wolfdietrich. A first version tells how the hero was sleeping beneath a tree one day when a nymph came out of the sea and hid his sword. She stands behind the tree and waits for him to wake up. She wears a scaly hat and is covered with aquatic plants and hair that falls from her chin to her feet. Her entire body is muddy and dank; her eye sockets are two fingers deep, and her feet are the size of spades; her forehead measures an ell in length. Although repulsive, she asks Wolfdietrich to marry her. If he consents, she will give him three kingdoms, for she rules over all that is covered by the sea. The knight objects, saying that if he were to wed her the devil would attend the ceremony. She then slips out of her scales and reveals herself to be a great beauty. Wolfdietrich, who was starving, asks her for something to eat and tells her he cannot get married until he frees his family. She then asks him to grant his brother to be her husband and gives him roots that will provide him with the courage of a lion and prevent him from suffering from hunger or thirst. She then tells him how to get back to Lombardy.

Fig. 72. Wild Woman. Hartmann Schedel, Liber Chronicarum, Nürnberg, 1493.

Fig. 69. Rome carrying Wolfdietrich. Das Heldenbuch (Strasbourg: Johann Prüss, circa 1483).

Fig. 71. Battle between a knight and a wild woman. Das Heldenbuch (Strasbourg: Johann Prüss, circa 1483).

In a second version the lady is named Else the Hairy, and she is in love with Wolfdietrich, who refuses to reciprocate because he believes her to be a devil. Furious, she casts a curse on him that causes him to lose his mind, and she takes his horse and his sword. When the hero regains his senses and sets off to find his weapons and companions, she creates a magic path that Wolfdietrich follows for twelve leagues before he sees her perched in a tree. She repeats her request, and he again rejects her. She bewitches the valiant knight a second time and cuts off a lock of his hair and his nails. He goes mad and wanders the forest like an animal for six months. His loyal vassal Berchtung, who had set out to find him, eventually runs into Else, and she relates to him all that has happened. However, God sends an angel to the woman, who orders her to break the evil spell. She obeys and asks Wolfdietrich if he would truly marry her. He agrees on the condition that she will consent to be baptized. She agrees and leads him to a ship. They cross the sea to Else’s kingdom, where there is a fountain of youth on a high mountain. She dives into it and reemerges as a ravishing beauty; all the hair that had covered her body remains in the fountain. Once baptized, she takes the name Sigeminne (“Victorious Love”).

RAVEN: The sacred bird of Odin. His ravens Huginn (“Thought”) and Muninn (“Memory”) travel across the world and then return to perch on his shoulders and tell him what they have seen and heard. The cries of a raven were believed to be oracular, and sacrifices were made to ravens when the petitioners sought to address Odin. The image of a raven was used as a battle emblem, and the Bayeux Tapestry shows William the Conqueror followed by a soldier carrying a raven banner. It was believed that victory would be assured if the banner spread out properly, but its bearer was doomed to die. Numerous personal names attest to the raven’s popularity. A Gallo-Roman statue from Compiègne depicts a male figure who has two ravens on his shoulders speaking into his ears, an image that is strongly reminiscent of Odin.

Grambo, Svart katt over veien, 124–25; Sylvia Huntley Horowitz, “The Ravens in Beowulf,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 80 (1981): 502–11.

Grambo, Svart katt over veien, 124–25; Sylvia Huntley Horowitz, “The Ravens in Beowulf,” Journal of English and Germanic Philology 80 (1981): 502–11.

RED: This color had a very pejorative connotation in ancient times. The first medieval German romance, Ruodlieb (eleventh century; written in Latin by a German poet), offers the advice to never make friends with a red-haired man: Non tibi sit rufus umquam specialis amico (V, 451). In the legend of Pope Gerbert there appears the phrase “Rufus est, tunc perfidus” (He is a red head, therefore perfidious). This has remained proverbial wisdom in the Tyrol, where it is said, “A red beard rarely hides a good nature,” and, similarly, in the Upper Palatinate with the proverb “Red hair and firewood don’t grow in good soil.” In Daniel von dem blühenden Tal (Daniel of the Flowering Valley), a thirteenth-century romance by Der Stricker, a malevolent red-haired man appears who hypnotizes all who hear him with his voice. He slits the people’s throats above a tub, for he takes a bath in blood once a week.

Resler, ed., Der Stricker: Daniel von dem blühenden Tal.

Resler, ed., Der Stricker: Daniel von dem blühenden Tal.

REGINN (“The Powerful One”): Smith and foster father of Sigurðr (Siegfried). He is the brother of Fáfnir, Otr, Lyngheiðr, and Lofnheiðr and the son of Hreiðmar. He forges the sword Gramr for Sigurðr, which the hero then uses to slay Fáfnir, who has changed into a dragon. After the hero is warned by the nuthatches that his foster father seeks to get rid of him, Sigurðr slays Reginn.

REVENANT:  DRAUGR

DRAUGR

RÍGR (“King,” the Old Norse word is a borrowing from Old Irish rí): Name given to the god Heimdallr in the Rígsþula, a gnomic Eddic poem of the fourteenth century. It is Rígr who establishes the three ancestral lineages of the slaves, peasants, and nobles.

RINDR (“Bark”?): Mother of Váli, Odin’s son who will avenge the death of Baldr. She is an Ásynja. In The History of the Danes, Saxo Grammaticus tells us that a Finn (Sámi) magician predicted to Othinus (Odin) one day that only Rinda could give him the son who would avenge Balderus (Baldr). Othinus tried to seduce the beautiful woman in various guises but finally made her ill and took advantage of her: “Imediately he touched her with a piece of bark inscribed with spells and made her like one demented, a moderate sort of punishment for the continual insults he had received” (III, 71, trans. Fisher). She gives birth to Bous, while Othinus is banished for his crime.

RISE, BERGRISE (German Riese, “giant”): A Scandinavian name for giants that live in the mountains. The rise is large and ugly and leads a life similar to that of humans with families, farms, and animals. In Norway place-names like Risabbakken (Rogaland), Risareva (Hordaland), and Risarøysa keep their memory alive.

ROCHELMORE: A mystical being of Switzerland who travels through the air making a noise that sounds like the grunting of a sow (Färlimore); in Grindelwald it is a portent of bad weather.

RÖKSTÓLAR (“Thrones of Judgment”): The thrones on which the Æsir sit when exercising their duties as judges and sovereigns.

ROME: The name of a wild woman in the legends surrounding the hero Wolfdietrich. She has black skin, and her hair is the color of a donkey’s coat. Wolfdietrich meets her when he is lost on the mountain. She gives him lodging in the castle where she lives with seven of her fellows. These women are most likely fairies, because they possess uncommon knowledge. The knight stays with them three days, after which Rome carries him under her arm, together with his horse, for a distance of twenty-two leagues and sets him down on the right path on the other side of the mountain.

RÖSKVA: Sister of Þjálfi and, like him, a servant of the god Thor. She was forced to enter into Thor’s service as reparation for the mutilation of his goats.

ROSSTRAPPE (“Print of the Horseshoe”): Name of a steep crag in the Harz Mountains of Germany. A gigantic shape of a horseshoe print can be seen on the edge of the Rosstrappe, which has given birth to a legend about its cause. Pursued by a giant named Bodo, Princess Emma leaped over the Bodotal (Bode Gorge) to land on this rock, and her horse left the print of his hoof in the stone. The giant failed to make the leap, however, and fell into the valley, thus giving his name to the river that flows there, the Bode.

Fig. 70. Rosstrappe. Illustration from a German textbook.

Similar legends exist in France (le Saut de la Pucelle) and in Spain (Lo Salt de la donzella), with both names meaning “the Maiden’s Leap.”

RÜBEZAHL: A type of legendary mountain spirit who was originally confined to the KrkonoÅ¡e Mountains (in German they are called the Riesengebirge, “Mountains of Giants”) of Bohemia and Silesia in the sixteenth century but has since spread into other regions. Rübezahl (“Turnip-counter”) is also called Riesezahl, Rübenzagel, and Rubinzalius. He is a solitary and multifarious demon who can appear alternately as a person, a thing, or an animal. He is sometimes friendly and will help lost travelers find their way, but if they mock him, he will either slap them or send them astray. The features of several different demons have become merged together in his form. Originally he was a spirit of the mines.

Peuckert, Deutscher Volksglaube des späten Mittelalters.

Peuckert, Deutscher Volksglaube des späten Mittelalters.

RUEL THE STRONG: Giantess or wild woman who appears in Wirnt von Grafenberg’s Wigalois (ca. 1204–1215). Her head is enormous, with long gray eyebrows, a large mouth, and huge teeth. She is as hairy as a bear and hunchbacked. Her breasts hang down like sacks, her feet are twisted, and her fingers are griffon claws. Seeking to avenge her husband, the giant Feroz, she attacks Wigalois and carries him off under her arm. She binds him and has the intention of killing him. However, the neighing of the hero’s horse scares her off, because she believes it to be the cry of a dragon. The author notes in passing: “A short night would age any man that shared her bed because she was so skilled at making love.”

RUGIVIT: War god of the Rugians. His statue, which was carved from the trunk of an enormous oak tree, stood in the city of Carenz (Garz, Rügen). It had seven heads, each topped by a hat, and seven swords. The god held an eighth sword in his hand in a threatening gesture.

Krantz, Wandalia, 164; Schwarz, Diplomatische Geschichte der Pommersch-Rügischen Städte Schwedischer Hoheit, 601–2.

Krantz, Wandalia, 164; Schwarz, Diplomatische Geschichte der Pommersch-Rügischen Städte Schwedischer Hoheit, 601–2.

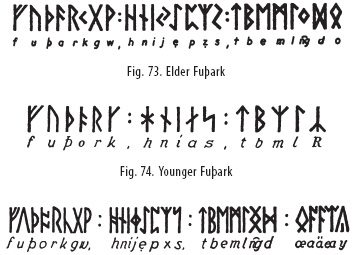

RUNES: The letters of the ancient Germanic script. Consisting of twenty-four signs, the runic alphabet appeared toward the end of the second century. The symbols themselves were probably modeled on an ancient Italic script. Because of the inherent difficulty in carving them, runes were used mainly for brief inscriptions, the bulk of which dealt with propitiation, protection, spells, and so forth. In later periods, notably during the Viking Age, they were often used for large and elaborate memorial stones.

The runic alphabet is called the Fuþark, so named after its first six letters in their traditional order. Each rune has a name, and the rune phonologically represents the first letter of that name. The rune names have been reconstructed based on linguistic evidence.

The original rune row of twenty-four letters is known as the Elder Fuþark. Over time, significant regional linguistic variations developed that affected not only the number of the runes but also their names and their phonological values. In the Viking Age a shorter sixteen-rune alphabet, known as the Younger Fuþark, was in use in Scandinavia. By contrast, in Frisia and England, a longer rune row developed; this is known as the Anglo-Saxon (or Anglo-Frisian) Fuþorc.

Fig. 75. Anglo-Saxon Fuþorc

The referents for the original rune names fall into five different categories or domains: the animal world (aurochs, horse, elk); weather (hail, ice, sun, water, day); plant life (good fruitful year, birch, yew, thorn); the human world (property/wealth, riding, boil[?], gift, joy, need, man, and estate); and, finally, the divine world (thurse/giant, Æsir god, Týr, Ingvarr/Freyr). The Old English Rune Poem, written during the first half of the ninth century, gives us insight into the meaning of the runes. Each of the poem’s twenty-nine verses begins with the name of a rune and then describes some of its qualities.

Runes have been found on carved stones, weapons, pieces of wood, in manuscripts, and quite frequently in charms. Here are examples of two sorts of common uses. On the Gallehus Horn, an ornate golden metal horn discovered near Tönder (Denmark) and dated to the fifth century CE, the runic inscription reads: “I, Hlewagast, son of Holt, made this horn.” The commemorative stone of Hällestad in Scania, erected to the memory of Toki, the son of King Gorm of Denmark, reads: “He did not flee at Uppsala. The young men erected a stone, strengthened by runes, in memory of their brother, on the mountain. They were your closest kin, Toki, son of Gorm.” An inscription that is magical in nature appears on the Stentoften Stone from Blekinge, Sweden: “To the new dwellers, to the new guests . . . Haþuwulf gave [a] fruitful year . . . powerful runes I hide here, a row of bright runes. Consumed by rage and [doomed to a] woeful death [will be] he who breaks this.”

Barnes, Runes; Düwel, Runenkunde; Elliott, Runes; Looijenga, Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions; McKinnell, Simek, and Düwel, Runes, Magic, and Religion; Musset, Introduction à la runologie; Page, Runes; Stoklund et al., eds., Runes and Their Secrets. A fine study of the matter can be read in the special issue devoted to runes of the journal Études Germaniques 52 (1997): 507–92, which includes an extensive bibliography.

Barnes, Runes; Düwel, Runenkunde; Elliott, Runes; Looijenga, Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions; McKinnell, Simek, and Düwel, Runes, Magic, and Religion; Musset, Introduction à la runologie; Page, Runes; Stoklund et al., eds., Runes and Their Secrets. A fine study of the matter can be read in the special issue devoted to runes of the journal Études Germaniques 52 (1997): 507–92, which includes an extensive bibliography.

RÜTTELWEIB, RITTELWEIB: One of the many names for a wood woman or bush woman; they are also called Buschweiblen in Westphalia or Fenngen in the Tyrol. She can be seen in the procession of the Wild Hunt. It is said that she steals children who are six weeks old or younger, or substitutes changelings for them.

CHANGELING

CHANGELING

RYLLA: The name given to an illness demon in some Norwegian charms.

RYMR (“Roar”): One of the bynames of the god Thor.