T

TANGIE: The name of a horselike monster in the Shetlands that lives in the depths of the ocean. Tides or storms inspire it to haunt the rocky coasts or sandy beaches in search of a maiden to abduct and wed.

Jean Renaud, “Le peuple surnaturel des Shetland,” Artus 21–22 (1986): 28–32.

Jean Renaud, “Le peuple surnaturel des Shetland,” Artus 21–22 (1986): 28–32.

TANNHÄUSER: The name of a troubadour who was active between 1228 and 1265. The legend that grew around him says the following. Tannhäuser was a German knight who after many long journeys came to the home of Lady Venus in Hörselberg. He stayed there awhile, surrounded by beautiful women, but his conscience began gnawing at him and he asked to take his leave. Lady Venus did all she could to keep him there, even offering him one of her companions as a wife. Tannhäuser responded that he did not wish to be damned for all eternity and left. He went to Rome to ask the pope for forgiveness. The pope gave him a staff and told him, “When this turns green again, your sins will be forgiven.” In despair, Tannhauser returned to the company of Lady Venus. The staff eventually flowered, but it was too late, and the knight will remain in the mountain until Final Judgment.

The first attestation of this legend is in 1515. Ludwig Tieck made an adaptation of it in 1800, and many other writers followed his example, including Heinrich Heine in 1836. In 1845, Richard Wagner wrote an opera that combined this legend with that of the minstrel singing contest of Wartburg.

Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, no. 170; J. M. Clifton-Everest, The Tragedy of Knighthood. Origins of the Tannhäuser-legend.

Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, no. 170; J. M. Clifton-Everest, The Tragedy of Knighthood. Origins of the Tannhäuser-legend.

TATZELWURM: Still called Beißwurm (“biting dragon”) and Stollenwurm (“dragon of the mine tunnels”), the Tatzelwurm is a dragon with two feet, a large head that is around eighteen inches, and a lizard’s body. It can stand up on its feet, and it has poisonous breath. It has a piercing gaze and makes earsplitting shrieks. It chiefly resides in the Alps, and the descriptions of it vary from one region to the next.

Joseph Freiherr von Doblhoff, “Altes und Neues vom ‘Tatzelwurm,’” Zeitschrift für österreichische Volkskunde 1, 5–6 (1895): 142–66; Doblhoff, “Zur Sage vom Tatzelwurm,” Zeitschrift für österreichische Volkskunde 1, 8–9 (1895): 261–65.

Joseph Freiherr von Doblhoff, “Altes und Neues vom ‘Tatzelwurm,’” Zeitschrift für österreichische Volkskunde 1, 5–6 (1895): 142–66; Doblhoff, “Zur Sage vom Tatzelwurm,” Zeitschrift für österreichische Volkskunde 1, 8–9 (1895): 261–65.

TELL, WILLIAM: The name of William Tell first appears around 1470 in a chronicle relating the birth of the alliance of the people of the mountainous Waldstätten region (Uri, Schwyz, Obwald, and Nidwald). The historical elements of this period became blended with legend. One day Tell refused to doff his hat to Gessler, a bailiff working for the Hapsburgs, beneath the Altdorf linden tree. The magistrate ordered him to shoot an apple off his son’s head with a crossbow arrow. This episode has been attached to Tell’s story and is reflective of a very ancient motif, that of the master shot, which appears earlier in the thirteenth-century work of Saxo Grammaticus, in the Þiðreks saga af Bern (Saga of Dietrich von Bern), and in the legend of Wayland the Smith. It can be seen in Friedrich Schiller’s 1804 play Wilhelm Tell (Act III, 3; IV, 1 and 3).

Helmut de Boor, “Die nordischen, englischen und deutschen Darstellungen des Apfelschußmotivs: Texte und Übersetzungen mit einer Abhandlung,” in Quellenwerk zur Entstehung der schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft 3/1, ed. Hans Georg Wirz (Aarau: Sauerländer, 1947), appendix, 1–53; Hans-Peter Naumann, “Tell und die nordische Überlieferung: Zur Frage nach dem Archetypus vom Meisterschützen,” Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde 71 (1975): 108–28; variants originating in Bavaria and in Schleswig-Holstein can be found in Petzold, Historische Sagen, vol. I, 442ff.

Helmut de Boor, “Die nordischen, englischen und deutschen Darstellungen des Apfelschußmotivs: Texte und Übersetzungen mit einer Abhandlung,” in Quellenwerk zur Entstehung der schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft 3/1, ed. Hans Georg Wirz (Aarau: Sauerländer, 1947), appendix, 1–53; Hans-Peter Naumann, “Tell und die nordische Überlieferung: Zur Frage nach dem Archetypus vom Meisterschützen,” Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde 71 (1975): 108–28; variants originating in Bavaria and in Schleswig-Holstein can be found in Petzold, Historische Sagen, vol. I, 442ff.

Fig. 83. William Tell. Illustration by Heinrich Vogeler.

THEUTANUS: Eponymous ancestor of the Teutons. Around 1240, Thomas of Cantimpré (De Natura rerum, III, 5, 40) recounts how his body was discovered on the banks of the Danube near Vienna. He measured ninety-five cubits (around 144 feet!), and his teeth were huge, larger than a palm leaf.

ÞJÁLFI: Companion and manservant of Thor. He entered into the god’s service to make up for some harm he caused: he had maimed one of the god’s goats out of ignorance and gluttony. He helped Thor in his battle against Hrungnir and slew Mökkurkálfi, the clay giant.

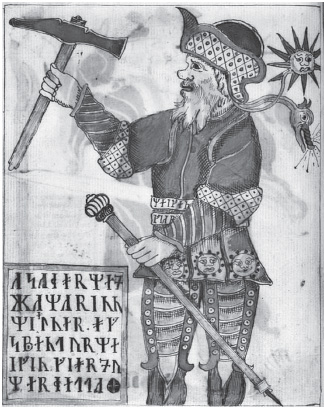

ÞJAZI: This giant is the father of Skaði, Njörðr’s wife. He is involved in the following story.

Odin, Loki, and Hœnir were traveling and had run short of food. They saw a herd of oxen in a valley and killed one. They tried to cook it to no avail, and they were wondering why.

They then heard a voice from the oak tree above them saying that he was the reason the meat would not cook. They looked up and saw an eagle, which continued, “If you will let me eat my fill of that ox, I will make it so that the oven will cook.”

The three Æsir accepted, but the eagle took both hams and both shoulders of the ox. Loki grew angry and struck a violent blow with a long pole at the eagle, and it began to fly off. But the pole remained stuck to the eagle’s back, and Loki’s hands were stuck to his end of it. Loki begged the eagle for a truce; the eagle accepted on the condition that Loki promise to bring Iðunn and her apples of rejunvenation out of Ásgarðr. Loki accepted, and a little later he lured Iðunn into a forest. Þjazi, still in the form of an eagle, carried her off and took her to Thrymheimr.

Fig. 84. Þjazi. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

Deprived of Iðunn’s apples, the Æsir began to age, and when they discovered Loki’s misdeed they threatened to kill him. With the help of Freyja’s falcon cloak, Loki then flew to Jötunheimr and arrived at the home of Þjazi, who was away. He changed Iðunn into a walnut, picked her up in his claws, and flew back to Ásgarðr as fast as he could. On his return the giant discovered the absence of his prisoner, assumed his eagle form, and launched himself in pursuit of her abductor. Seeing Loki arrive with Þjazi right at his heels, the Æsir built a fire that burned the eagle’s feathers. The giant fell to the ground, and the Æsir killed him.

The rest of the story tells how Skaði obtained compensation for this killing. Odin, among other things, cast Þjazi’s eyes into the sky where they became stars.

Eugen Mogk, “Þjazi,” in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, ed. Johannes Hoops, 1st ed. (Straßburg: Trübner, 1918–1919), vol. IV, 321.

Eugen Mogk, “Þjazi,” in Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde, ed. Johannes Hoops, 1st ed. (Straßburg: Trübner, 1918–1919), vol. IV, 321.

THOR (“Thunder”; Old Norse Þórr; Old High German Donar; Old English Þunor; Old Saxon Thunær): Son of Odin and Jörð, his wife is Sif, with whom he has two sons, Magni (“Strength”) and Móði (“Courage”), and a daughter, Þrúðr (“Power”). He lives in Þrúðvangr or Þrúðheimr, and his hall is called Bilskírnir; it has five hundred doors. His servants are Þjálfi and his sister Röskva. Thor owns two goats, Tanngnjóstr (“Teeth-gnasher”) and Tanngrísnir (“Teeth-barer”), who pull his chariot when he travels. Thor has a red beard and is endowed with a fabled appetite; he is truculent and quick to anger. He is also called Ásaþórr (“Thor of the Æsir” or “Æsir-Thor”) and Ökuþórr, which roughly translates as “Thor the Traveler” or “Thor the Driver.”

He is the strongest of gods and men. He owns three precious objects: the hammer Mjöllnir, with which he massacres the giants; a pair of iron gloves, necessary to wield the hammer; and a belt that doubles his strength. He represents a military function (the second function, according to Dumézil’s classification) and corresponds to the Roman Mars and Hercules, as well as the Indian Indra. In Gaulish (Celtic) mythology his counterpart is Taranis. Thor is the champion of the Æsir,

whom he defends against the giants ( GEIRRÖDR, HRUNGNIR, HYMIR, SKRÝMIR, ÞRYMR, ÚTGARÐALOKI).

GEIRRÖDR, HRUNGNIR, HYMIR, SKRÝMIR, ÞRYMR, ÚTGARÐALOKI).

Fig. 85. Thor

Fig. 86. Thor and the Midgard Serpent. Runestone carving from Altuna, Sweden.

He is also the initiator of young warriors ( MÖKKURKÁLFI). In certain respects he is akin to the proto-Germanic *Tiwaz (the deity that evolved into the Norse Týr), several whose of attributes Thor seems to have assimilated over time.

MÖKKURKÁLFI). In certain respects he is akin to the proto-Germanic *Tiwaz (the deity that evolved into the Norse Týr), several whose of attributes Thor seems to have assimilated over time.

Thor is also connected to the Dumézilian third function (fertility, fecundity). He rules over thunder and lightning and wind and rain (fertilizing), a feature that strongly survived in the beliefs of certain Lapplanders who had assimilated Thor into their native world-view. He shares the dead with Freyja and Odin but receives only the thralls (“slaves,” although here this perjorative term is most likely just a reference to peasants as opposed to nobles).

Thor is famous for a number of exploits: his fishing expedition to try to catch the Midgard Serpent (whose venom will later kill him at Ragnarök), his resuscitation of his goats, and his journeys to the land of the giants. He is the preeminent Viking god, one of the rare deities to have survived in the medieval Danish ballads (folkeviser). His name is still evident in that of the weekday Thursday, “Thor’s day” (cf. Old Norse þórsdagr and modern German Donnerstag). The frequent appearance of Thor in place-names as well as in personal names attests to his popularity. In France, Thor survives in the Norman name “Turquetil” (from Old Norse Þórketill, “Thor’s Cauldron”).

Etymologically, Thor is the “thunder,” which can be found in lightning and the noise that accompanies the flight of his hammer.

MJÖLLNIR, VIMUR

MJÖLLNIR, VIMUR

Arnold, Thor; John Lindow, “Thor’s Visit to Útgarðaloki,” Oral Tradition 15/1 (2000): 170–86; Riti Kroesen, “Thor and the Giant’s Bride,” Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 17 (1982): 60–67; Carl von Sydow, “Tors färd till utgård,” Danske Studier, 1910: 65–105, 145–82.

Arnold, Thor; John Lindow, “Thor’s Visit to Útgarðaloki,” Oral Tradition 15/1 (2000): 170–86; Riti Kroesen, “Thor and the Giant’s Bride,” Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 17 (1982): 60–67; Carl von Sydow, “Tors färd till utgård,” Danske Studier, 1910: 65–105, 145–82.

Fig. 87. Thor. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

ÞORGERÐR HÖLGABRÚÐR, HÖRÐABRÚÐR: Goddess to whom a temple in Norway was dedicated in the tenth century; her sister is Irpa. She may be a local deity and patron of Hördaland. The best source of information on her is the Jómsvíkinga saga (Saga of the Jómsvíkings), written down around 1200. Þorgerðr granted victory to the jarl (earl) Hakon when he sacrificed his son to her. A dark, black cloud arrived at top speed to the battlefield, followed by a hailstorm, thunder, and lightning. The men gifted with second sight saw Þorgerðr there, and it seemed to them that an arrow flew from each of her shining fingers, killing a man each time.

Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr is most likely a protective goddess of fertility, as the denomination -brúðr is associated in other texts exclusively with the Vanir—therefore agrarian—deities. In her temple at Hlaðir (present-day Lade, Norway) an image of her stood beside one of Thor in his chariot and one of Irpa. She wore a gold bracelet and a hood.

According to Snorri Sturluson, Þorgerðr was the daughter of Hölgi, or Helgi; according to Saxo Grammaticus, she was the daughter of Gusi, King of the Finns, and she wed King Helgi of Hálogaland.

Boyer, La Grande Déesse du Nord, 84.

Boyer, La Grande Déesse du Nord, 84.

ÞORRI: Name of the winter month going from mid-January to mid-February. It is also that of a giant in the family of Fornjótr. Þorri is the son of King Snaer (“Snow”), and he had two sons, Norr and Gorr (“Wind?”), and a daughter, Gói (“Powder Snow?”).

ÞRÍVALDI (“Triply Powerful”): Nine-headed giant killed by Thor in a myth that has not come down to the present.

ÞRÚÐR (“Power,” “Strength”): Name of a valkyrie as well as the daughter of Thor. It can be found in the name Gertrude (Old Norse Geirþrúðr). The German cognate Drude means both “witch” and “nightmare.”

VALKYRIE

VALKYRIE

ÞRÚÐGELMIR (“The Powerful Shouter”): Six-headed giant, son of Aurgelmir and father of Bergelmir, all frost giants.

ÞRÚÐHEIMR (“World of Strength/Force”): Thor’s domain in Ásgarðr.

ÞRÚÐVANGR (“Force Field”): Thor’s domain in Ásgarðr. This name alternates with Þrúðheimr.

ÞRYMGJÖLL (“The Resounding One”): An iron gate sealing the home of Menglöð, the guardian of the Gjallarbrú bridge, on the road that leads to the underworld. The sons of Sólblindi, the dwarves, forged it. Anyone who lifts it off its hinges is paralyzed immediately.

ÞRYMHEIMR (“World of Noise”): The home of the giant Þjazi and his daughter, Skaði.

ÞRYMR (“Noise”): The giant who once steals Thor’s hammer. Having borrowed Freyja’s feather cloak, Loki makes his way to Jötunheimr, where Þrymr tells him: “I hid the hammer eight leagues beneath the sea. No man can recover it unless I am given Freyja for my wife.” Taking Heimdallr’s advice, Thor disguises himself as the giant’s would-be bride and, accompanied by Loki, recovers his hammer and slays Þrymr and his entire family.

ÞUNOR: Anglo-Saxon name of Thor/Donar. In Old Saxon it is Thunær.

THURSE: The designation for a race of giants whose existence is attested in all the Germanic countries (Old Norse þurs; Old English þyrs; Old High German Turs/Durs). It is also the name of the rune *þurisaz (in Old Norse the rune name becomes þurs), which is transliterated as /th/. The thurses are harmful by nature; the best known of them are the frost giants (hrímþursar), who are all descendants of Bergelmir and his wife. Attestations of the thurses are rare in Germany, but the ones we do find show that these giants were known there too. For example, in the legend of the founding of a monastery in Wilten

near Innsbruck, the giant that opposed the civilizing hero ( HAYMON) was named Thyrsus.

HAYMON) was named Thyrsus.

TUSS

TUSS

TILBERI (“Fetcher”): In Icelandic folk tradition the tilberi (also known in some areas as the snakkur, the “snakelike imp”) is a being that steals milk from the livestock of neighbors and then transforms its booty into gold. Only women who are competent in sorcery can create a tilberi. This is done in the following manner: The woman must dig up a human rib bone from a grave on Whitsunday (Pentecost), swaddle it in gray wool, and carry it between her breasts. During communion on each of the next three Sundays she spits sacramental wine on the bundle, which will bring it to life. The woman then has to carve a nipple on the inside of her thigh; the tilberi will attach itself to the nipple and feed, growing in size and strength.

Árnason, Icelandic Legends, vol. II, xcii–xcv; Heurgren, Husdjuren i nordisk folktro; Kvideland and Sehmsdorf, eds., Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, 179; Þorvarðardóttir, Brennuöldin, 175–84; Wall, Tjuvmjölkande väsen i äldre nordisk tradition. See also the information on the tilberi that can be found at the website of Strandagaldur, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft:

www.galdrasyning.is.

Árnason, Icelandic Legends, vol. II, xcii–xcv; Heurgren, Husdjuren i nordisk folktro; Kvideland and Sehmsdorf, eds., Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend, 179; Þorvarðardóttir, Brennuöldin, 175–84; Wall, Tjuvmjölkande väsen i äldre nordisk tradition. See also the information on the tilberi that can be found at the website of Strandagaldur, the Museum of Icelandic Sorcery and Witchcraft:

www.galdrasyning.is.

*TIWAZ: Proto-Germanic name of the god that evolved into the Old Norse Týr (Old English Tiw, Tig, or Ti; Old High German Ziu).

TOGGELI, DOGGELI (“Little Oppressor”): The name of the entity in Switzerland known as the nightmare (Alp, Mahr, Trude). It is also the name of a night butterfly and a name used to designate dwarves.

TOMPTA GUDHANE (“The Gods of the Building Terrain”): Swedish place spirits. They were granted one-tenth of the livestock, bread, and drink, which is the tacit contract negotiated with them so that they will not obstruct the smooth operation of the farm.

Lecouteux, The Tradition of Household Spirits; Lecouteux, Demons and Spirits of the Land; Hultkrantz, ed., The Supernatural Owners of Nature.

Lecouteux, The Tradition of Household Spirits; Lecouteux, Demons and Spirits of the Land; Hultkrantz, ed., The Supernatural Owners of Nature.

TOMTE:

HOUSEHOLD/PLACE SPIRITS, NISS

HOUSEHOLD/PLACE SPIRITS, NISS

Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 51–54.

Holbek and Piø, Fabeldyr og sagnfolk, 51–54.

TOMTEBISSENS STUGA (“Tomte’s Room”): Name of a large stone located on a hill of Västmanland (Sweden), under which a place spirit lived.

Fig. 88. Tomte. Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, Rome, 1555.

TOMTETRÄD (“Tomte Tree”): This is the Swedish designation of the tutelary tree that grows in the farmyard or garden on which the prosperity of the household or farm depends. No harm should be done to it. On Thursday evening, to stave off misfortune or illness affecting men or animals, milk or beer would be poured on its roots, which is a form of propitiatory sacrifice to the spirit that has made its home there. This tree is also called tuntré in Iceland, and vårträd and bosträd in Sweden.

Martti Haavio, “Heilige Bäume,” Studia Fennica 8 (1959): 35–48.

Martti Haavio, “Heilige Bäume,” Studia Fennica 8 (1959): 35–48.

TREES: There is evidence for tree worship throughout the medieval West. The species most often mentioned in the Germanic countries are the ash (Yggdrasill, the cosmic tree, is an ash, and the first man was created from the trunk of an ash), the aspen, and the linden tree, which is extremely popular east of the Rhine. One Norse myth fragment says that a rowan branch saved Thor. The sacred space inside of which a duel took place was marked off by hazel posts. The most famous tree is the Geismar oak (Hesse) that was cut down by Saint Boniface and which was most likely a representation of the Irminsûl, the name for the cosmic tree in medieval Germany. Less well known but equally important is the sacred yew that grew by the temple in Uppsala, Sweden, where sacrifices were performed. In his History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen, Adam of Bremen (eleventh century) says this about the temple:

The sacrifice is of this nature: of every living thing that is male, they offer nine heads. . . . The bodies they hang in the sacred grove that adjoins the temple. Now this grove is so sacred in the eyes of the heathen that each and every tree in it is believed divine because of the death or putrefaction of the victims. Even dogs and horses hang there with men. (trans. Tschan)

A more recent scholium adds: “Feasts and sacrifices of this kind are solemnized for nine days. . . . This sacrifice takes place about the time of the vernal equinox.”

TRIGLAF (“Three-headed One”): God of the Pomeranians worshipped in Julin and Stettin. His three heads (Slavic tri + glava) indicate that he ruled over heaven, Earth, and the underworld. His statue had a gold cover over its face so he would not see the evil deeds of men. Triglaf owned a fat, black, sacred horse that was forbidden for anyone to ride; its saddle was made of gold and silver, and a priest was assigned to its service. This horse served as an oracle. The monk Idung of Prüfening says this in his Life of Othon, Bishop of Bamberg (II, 11), written before 1144: “Having planted a number of spears here and there, they then walked Triglaf ’s horse through them. If he did not touch any of them, the omen was considered favorable to leave on horseback for a pillaging expedition, but if he trounced even one of them, they took that as a sign that the god forbade them to mount their horses.” Herbord (died 1168), a monk of Michelberg, states more explicity that there were nine spears, and the horse went back and forth between them three times (Dialogus de Vita S. Ottonis, II, 26 and 31). According to the author of the Knýtlinga saga (Saga of Cnut’s Descendants, chap. 125), a history of the Danes from 950 to 1190, written around 1256, Triglaf was a god of the Rugians. The inhabitants of Stettin worshipped a walnut tree, from which a spring seeped, because they believed Triglaf lived there.

Kantzow, Pomerania, vol. I, 107–11; Micraelius, Antiquitates Pomeraniae, vol. I, 150.

Kantzow, Pomerania, vol. I, 107–11; Micraelius, Antiquitates Pomeraniae, vol. I, 150.

TROLDHVAL: A monstrous cetacean of the northern seas that sinks ships. This beast appears to be a variant of the Kraken.

KRAKEN

KRAKEN

TROLL: Name of a race of ugly and malevolent giants that are always associated with water. The word is also used with the sense of “monster,” “demon,” and “revenant.” Today trolls have become dwarves, and, in the Shetland archipelago, they are called trows. They are malicious spirits who are often deformed and generally live in forests.

Fig. 89. Trolls. Drawing by Johann Eckersberg for

the fairy tale The Gold Bird, 1850.

In folktales the troll possesses several heads that are able to grow back unless they are severed with a single blow. They have long noses and have either long hair or are hairy all over. It is also an ogre and creature of the night. It is turned to stone by sunlight. Its death can also take the following form: it explodes with anger when it realizes that it has been tricked.

In Norway its memory lives on in numerous proverbs; for example: “When one speaks of trolls, they are not far away” (which corresponds to “Speak of the Devil [and he will appear]”) and “A fine face can hide a troll” (i.e., “Don’t judge a book by its cover”). Another saying is “When the sun rises, the trolls die.”

In Norway there are one hundred place-names coined from “troll” and five hundred others that contain the word. It should be noted that the word never appears in village names or personal names.

GRÝLA, JÖTUNN, RISE

GRÝLA, JÖTUNN, RISE

Amilien, Le troll et autres créatures surnaturelles dans les contes populaires norvégiens; Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 94–139; Lindow, Trolls.

Amilien, Le troll et autres créatures surnaturelles dans les contes populaires norvégiens; Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 94–139; Lindow, Trolls.

TROW: The name given to trolls in the Shetlands, the archipelago where the Norwegians began settling in the ninth century. Small in size, gray clad, and very ugly, the trows resemble humans. They like music and to eat and drink inordinately. They live in caves in cliffs or near the lochs, and time passes more slowly in their world than it does for humans.

Trows only come out after sunset and appear most frequently during winter when the nights are long. It is said that they will turn to stone if sunlight catches them by surprise. This is how a stone circle in Fetlar, which has two other standing stones in its center, got its name of Haltadans. These stones would be trows that were changed into rock while dancing, with the fiddle player and his wife in the middle. It is said that to overhear a trow conversation is a good omen but that to see a trow, share his meal, or accept a reward from him can bring misfortune. On the other hand, when a trow has forgotten some personal possession by accident, it is a guaranteed good-luck charm for its new owner.

They have a tendency to steal babies at times, especially little girls, and to replace them with a sickly, stupid infant ( CHANGELING), and the explanation for this is that they can only procreate boys. To rescue the child one must obtain a pail of seawater and three pebbles, pass the child through the flames of a peat fire, burn its effigy, and then feed it during its convalescence with three kinds of food offered by nine women, each of whom has given birth to a son.

CHANGELING), and the explanation for this is that they can only procreate boys. To rescue the child one must obtain a pail of seawater and three pebbles, pass the child through the flames of a peat fire, burn its effigy, and then feed it during its convalescence with three kinds of food offered by nine women, each of whom has given birth to a son.

They will also steal milk cows, and a popular story tells of the steps that an old woman named Maron took to wrest her cow from the trows’ power. With a torch in hand, she walked around the cow three times, poking it each time with a blade; then she waved a page of the Bible over the animal while speaking incomprehensible spells in the Old Norse tongue. Stuck in a bucket of tar tied around the animal’s neck, the torch gave off a thick smoke. Maron then pulled the tail of a cat three times, which had been placed on the animal’s back, and afterward fed it three crabs of a very specific kind. As a result, the animal was freed of the trows.

Trows sometimes need the services of humans. It is told how a midwife, whose skills were well known, had just put her fish on to cook for dinner when the trows abducted her to assist at a birth. When she returned home two weeks later she simply asked her husband if the fish was cooked yet.

To avoid attracting the vengeful anger of the trows, people take pains not to lock the entrance door to the house, or that of a closet, and the house is tidied up before going to bed, to ensure their displeasure is not aroused. Young children and animals can be protected from them with the sign of the cross and by leaving an open Bible near the child; animals can be protected by placing two sheafs of straw in the form of a cross nearby. A knife also renders trows powerless. A black rooster, the only one capable of detecting an invisible presence, was also very useful, especially at the approach of Christmas.

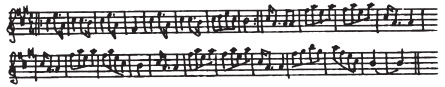

During the winter of 1803, Gibbie Laurenson of Gruting went to grind grain at the water mill of Fir Vaa. Dozing near a small peat fire, he suddenly heard a group of trows who entered and sat around the fire, thinking him to be asleep. A woman changed her baby’s diaper and hung it to dry on Gibbie’s thumb. One of the trows then said, “What are we going to do to this sleeper?” “Leave him alone,” responded the woman, “he is not wicked! Tell Shanko to play him a tune!” And Shanko played a tune on his fiddle, after which the entire group left. Gibbie whistled this tune to his son, who was a fiddle player. His son named it “Fader’s ton” (Papa’s Tune), but it was later given the name of a loch near the Fir Vaa water mill: “Winyadepla.” Here is the music:

Fig. 90. Papa’s Tune

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 164–67; Briggs, Dictionary of Fairies, 413–15.

Arrowsmith and Moorse, A Field Guide to the Little People, 164–67; Briggs, Dictionary of Fairies, 413–15.

TRUTE:

DRUDE

DRUDE

TUISTO (“Double”): The information we have about this god comes from Tacitus. Tuisto is born of the earth, which makes him a son of Nerthus. Apparently by himself he engendered the first human being, who was named Mannus, which corresponds to Manu, son of Vivasant in Vedic cosmogony, and to the Phrygian Manès. Tuisto is certainly an androgynous deity; he shows a clear kinship with yama from the Rig Veda and with the Norse Ymir.

TÜRSCHT/DÜRST: The name of the Infernal Hunstman in Switzerland. The Türscht is accompanied by a large sow and her piglets. He arrives from the east with bad weather. His retinue is called “Dürst’s Hunt” (Dürstengejäg).

Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 59; Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, no. 269; Elsbeth Liebl, “Geisterheere und ähnliche Erscheinungen,” in Atlas der schweizerischen Volkskunde, commentary, 2nd part (Basel: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Volkskunde, 1971), 768–84.

Vernaleken, Alpensagen, 59; Grimm, Deutsche Sagen, no. 269; Elsbeth Liebl, “Geisterheere und ähnliche Erscheinungen,” in Atlas der schweizerischen Volkskunde, commentary, 2nd part (Basel: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Volkskunde, 1971), 768–84.

TUSS(E)/TASS(E): In the folklore that surrounds the underground dwellers, this name, a derivative of thurse, designates spirits and land spirits that are the inhabitants of mounds and mountains. In Sweden (Uppland, Värmland) and in eastern Norway (Austlandet), this term means “wolf.” In Vestragothia this name was applied to a man suspected of being a werewolf. Tussen is also the name given in Norway to the black cat of the sorcerer or witch, when it is not called a trollkatten, “troll-cat.”

THURSE, UNDERGROUND DWELLERS

THURSE, UNDERGROUND DWELLERS

TWILIGHT OF THE GODS: Popular and Wagnerian name for the eschatological battle—it is based on an erroneous translation of the word ragnarök, which can be properly understood as meaning the “judgment (or destiny) of the ruling powers (gods).”

RAGNARÖK

RAGNARÖK

TÝR (“God”; Proto-Germanic *Tiwaz; Old English Tiw, Tig, Ti; Old High German Ziu): This Æsir god is either the son of Odin or of the giant Hymir. Structurally, he alternates with Odin like Mithra does with Varuna in Sanskrit mythology. He represents war as well as the exercise of law: he is the jurist god representing the forces that protect the order of the world. He is the patron of the Thing, the assembly of free men where legal cases are settled. In a Germano-Roman dedicatory inscription found near Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, a reflex of Tiwaz is certainly the god that underlies the name Mars Thingsus.

Fig. 91. Týr

Fig. 92. The god Týr confronts the wolf Fenrir during Ragnarök. Illustration by Ólafur Brynjúlfsson, Snorra Edda, 1760.

The sole myth we have about Týr relates the following: Seeing that the wolf Fenrir was growing larger, the Æsir grew alarmed and decided to shackle him. When they slipped the fetter called Gleipnir on him after two fruitless attempts, the now suspicious Fenrir demanded that a god place his hand in his mouth as a pledge of their good intentions. Týr agreed to this condition, and his hand was bitten off when Fenrir realized he could not break his bonds. Týr is the prototype for the hero whose sacrifice saves the world from chaos; in Rome his counterpart would be the one-armed Mutius Scaevola, and in Celtic epics it would be Nuada of the Silver Hand.

Etymologically, the name Týr is cognate to the Sanskrit dyaus, the Greek Zeus, the Latin deus, and the Old Irish día. The god’s name is evident in the weekday name “Tuesday” (from Old English tiwesdæg, “Tiw’s day”; cf. Old Norse týsdagr), and the rune corresponding to the letter /t/ is also named after him. Numerous place-names attest to his worship.

Régis Boyer, “La dextre de Týr,” in Mythe et Politique, ed. François Jouan and André Motte (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1990), 33–43; Kaarle Krohn, “Tyrs högra hand, Freys svärd,” in Festskrift til H. F. Feilberg (Stockholm: Norstedt & Söner, 1911), 541–47.

Régis Boyer, “La dextre de Týr,” in Mythe et Politique, ed. François Jouan and André Motte (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1990), 33–43; Kaarle Krohn, “Tyrs högra hand, Freys svärd,” in Festskrift til H. F. Feilberg (Stockholm: Norstedt & Söner, 1911), 541–47.