TOMORROW MAKES YOU TENSE?

FUTURE

What will the crossword of the twenty-first century look like?

We have declared that the first crossword was printed on December 21, 1913, in the New York World newspaper. Arthur Wynne’s “Word-Cross” was the rudimentary grid-plus-clues, definitions-lead-to-answers puzzle from which all others—Swedish and Japanese, straight and cryptic—have developed.

But is that definitely, indubitably true? The years following the American Civil War saw a flourishing of periodicals for veterans, keeping alive the camaraderie of the Union and Confederacy groupings, sprinkling in some reportage . . . and the odd puzzle.

The Neighbor’s Home Mail described itself as the “most intensely interesting Soldier paper published in this or any other country.” Also part temperance journal, the Mail urged former Union soldiers to subscribe in order to preserve “the little incidents and precious memories which fill the bosom of every honored veteran,” adding, “Every Soldier should write jokes for it!”

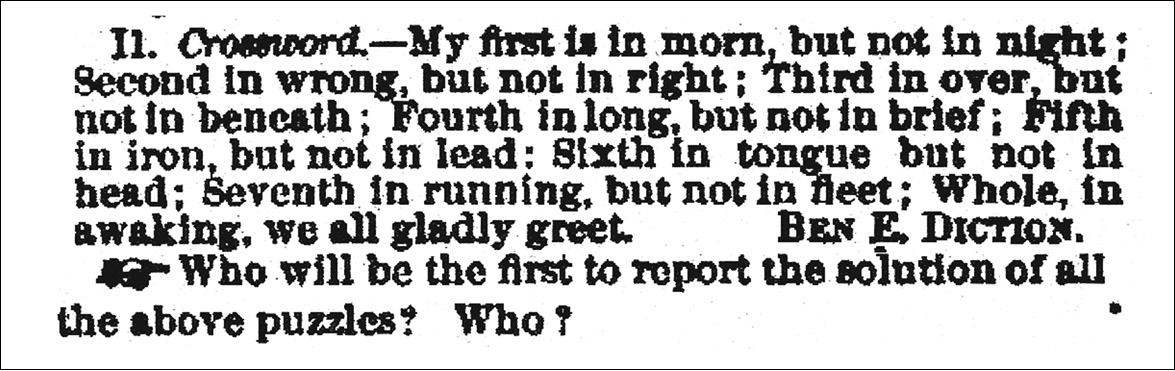

In the edition for October 1874, the section of puzzles headed ENIGMATICAL PROPOSITIONS contained this challenge:

Is this crossword a crossword? Well, yes and no. Surely, goes the case for yes, a puzzle called a crossword that asks the solver to manipulate interlocking words is a crossword puzzle. But, counters the case for no, where is the grid? Ah, remarks the yes, but Arthur Wynne’s grid was different from those we see today. It was a diamond rather than a square, and had a strange system of numbering the clues, proving that a crossword can look quite unlike today’s puzzles and still count as a crossword . . .

To answer this question is not merely to split hairs; it helps us understand what the future of the crossword might be.

The chief current method of distributing a puzzle is to squish a bunch of trees until they become thin sheets of paper, then spray them with ink derived from soy juice in the shape of a grid and clues, and surround them with all manner of investigations, opinions, and advertisements. Good luck persuading a deep-pocketed entrepreneur of the sustainability of that business model.

In 1874 periodicals crammed the maximum content into the paper available, setting the type small and close together, and the nineteenth-century solver completed the puzzles on a separate sheet or in his or her head. By 1913, there was more space and more scope for diagrams, pictures . . . and grids.

The Neighbor’s Home Mail “crossword” and Wynne’s diamond each took a form appropriate to the workable technology of the day. As the lead blocks of hot metal gave way to digital type, the number of possible grids expanded. Crosswords have shifted with technology, and they’re about to do so again.

We can understand the crossword in its current form as a result not just of the brains of the pioneering constructors but also of the possibilities of World War I–era printing.

As such, the crossword comes with a set of loose assumptions that are entirely dependent on its physical form. If a crossword comes into your consciousness by means of a newspaper, it means that certain things are expected of you, the solver:

• you will need to furnish yourself with extra kit, i.e., pencil or pen

• said crossword will be two-dimensional

• you will be expected to complete or abandon said crossword on the day of its publication, in order to make “room” for the next one

• you need not by default time the solve; the constructor cannot directly invite solvers to go into competition with one another

• the constructor must use the printed word, always in black, as the basis for clues and answers

None of these, in terms of crossword pleasure, is a shortcoming, but they all begin to seem a little arbitrary when you consider what’s happened to the medium the puzzle originated in. The decline in print readership is not going away. This is explainable in part by the fact that there’s nothing about a newspaper’s content that demands physical form—except perhaps the crossword in its current form: the final reason for newsprint to be printed. In newsrooms and editors’ offices, crosswords are considered important for loyalty and newsstand sales. This is largely based on anecdote and hunch, so I decided to commission some research to see what the numbers look like in the UK.

I discovered that around three in ten British adults attempt a crossword at least once a week, and that of solvers as a whole (72 percent solve at least occasionally), one in five says that his or her choice of newspaper has been influenced by its crossword. Newspaper proprietors might want to consider whether it’s the puzzle page that is keeping physical sales from falling to zero, and constructors might feel emboldened to ask for a long-overdue pay raise.

However, even taking the most positive interpretation—that crosswords are the only remaining reason for buying a physical copy of a newspaper—the crossword approached its centenary year treading water rather than powering forward in a butterfly.

Crossworders, both constructors and solvers, might benefit from their puzzle of choice switching to another paper medium, or ponder how the experience of a puzzle with the same grid and clues might change its form in different mediums: newsprint, online (on-screen or printed out), and apps for smartphones and tablets.

On paper, the crossword is a physical activity, albeit not one that is likely to make practitioners break into a sweat. For some, the pleasure is tactile.

Orlando—a staggeringly prolific constructor who has been in the business since 1975—created a crossword site in the early days of the World Wide Web; in 2012 he reflected that online solvers seem to prefer to see on-screen something very like what they see on paper. “There’s no demand for the bells and whistles,” he noted—those potential bells and whistles including “hyperlinks, sound, pictures, video, and so on.” Just use your imagination . . .

For those solvers accustomed by school to completing exercises by making marks on paper, who knows, there may remain in the future a vestigial two-dimensional form of the crossword. If the experience of home printing ever becomes less horrific than it is now, he or she may be printing off a daily puzzle rather than buying it from a kiosk, surrounded by all that other bumf.

One vision of this future comes from the London technology company Berg Cloud, which has produced a small home printer that automatically and inklessly produces, each morning and on thermal paper, something that is a little like a newspaper, but not quite, the aim being to reduce the cost and bother of choosing material and running it through a conventional printer. Users choose from features such as news, to-do lists, and puzzles for consumption on the bus or train, for example: The available items include sudokus and a super-quick version of the London Times crossword that contains one across and one down clue (super-quick, that is, assuming that they are the right two clues for your mood on a given weekday).

After the initial setup of the Berg Cloud printer, the puzzles are simply there, every day, just like they are in the newspapers. Indeed, the past propagation of puzzles is explained in part by their presence in a paper. The crossword might not be your destination when you buy a paper—and, typically, it doesn’t have anything to do with news—but a sufficiently long journey or a day with sufficiently grim reports might divert you to the crossword page: the only part of a paper that offers instant interactivity. The potential new solver is buying a crossword without realizing that he or she is doing so. But as newspapers become sprawling websites, some with a separate price package for the puzzles, the cost of entry rises.

Even for the seasoned and paid-up solver, the digital crossword is in danger of getting lost. On a smartphone or tablet, every other format of entertainment and communication is converging to jostle for the limited attention of the user of a single device—and most of the other “gaming” options are germane to their form, asking to be swiped, tilted, stroked, and tapped in new and gratifying ways: the touch screen equivalents of Orlando’s “bells and whistles.”

Such things are not alien to the crossword: As early as 1982 the American cryptic evangelist Henry Hook, whose career was described in The New Yorker as “one long effort to subvert our safe assumptions about puzzles, to make them as unsettling and unpredictable as art,” showcased another approach. It was a puzzle called “Sound Thinking,” in which many of the clues were announced over a loudspeaker, his contribution to the 1982 US Open Crossword Puzzle Championship, and a perfect ten of context plus content.

The challenge for crossword constructors and editors is to make wordplay work in the devices that are replacing print. New types of clue, using nonverbal hints, seem certain to emerge: Some may become part of the standard armory; some will branch off to make new kinds of puzzles, using colors, sounds, and shapes, which may or may not be called “crosswords.”

So far, most of the features publishers have added to crosswords have been along the same lines as those that adorn news: shareability and other social accessories such as leaderboards for the speediest solvers (see the chapter FAST above). But crosswords are not like news; they’re not made up of facts but are abstract edifices in which words are spelled out in unconventional directions. Those directions currently number two—across and down—but more are possible.

One possible direction of travel is suggested by another look at The Neighbor’s Home Mail and the puzzle in its twentieth-century incarnation. The 1874 “crossword” could be re-presented as a straight line of cells into which the solver writes the word MORNING: essentially a single across entry. For newsprint crosswords, the “grid” metaphor expands the area of play to a plane. Now screens can take their users in more than two dimensions, and metaphors other than a grid or a plane may explode into view while the crossword remains recognizable as a crossword.

The constructor Eric Westbrook is a teacher; he is also legally blind. For him, there is nothing inevitable about limiting the directions of clues to across and down, and he has quietly shown an amazing way of subtly rethinking the crossword.

When Westbrook constructs a puzzle, the analogy he uses is an apartment block. Each square becomes a room, and the words may be spelled out in front of you, to your right, or down through the stories beneath your feet. While the crossword is more engrossing, solving it does not, as you might suspect, take a lot of getting used to: The solver soon forgets that there’s anything out of the ordinary going on and engages with the clues and entries.

As Eric points out, most solvers could walk through their own homes blindfolded. “I walk around three-dimensional grids until I know them inside out and all the letters are in their places. It’s not quick—but it’s certainly easier than doing a school timetable.” Here is a partially filled grid in which, if you adjust your eyes to reading in different directions, you can see the answers starting from square one, CHARING operating as an across, CHALK as a regular down (now going away from the solver) and CROSS reading (down) down.

Currently, Eric’s puzzles exist in a two-dimensional medium. Having filled his grids, he recruits established constructors to set the clues and prints the puzzles as calendars to raise money for children’s charities. He is certainly a maverick, but that doesn’t mean he’s completely out on his own: There are others, too, building in a third dimension. The Listener puzzle series (see the chapter SONDHEIM above) may be printed on the flat pages of the London Times, but it has asked its solvers to cut out its grids and restructure them in the form of a Rubik’s Cube, the one-sided loop known as a Möbius strip, and even the abstract single-surfaced Klein bottle. If any puzzle embraces time as the fourth dimension—a grid in which the correct letters depend on what day it is, say—it will surely be The Listener.

Another exciting new direction was suggested by Tracy Gray in a New York Times puzzle based on the “right turn on red” traffic instruction. In its down clues, if the solver encountered the letters RED, he or she changed direction, so, for example, INSHREDS, CLAIREDANES, and CHEEREDON become:

|

|

I |

C |

|

C |

|

|

N |

L |

|

H |

|

|

S |

A |

|

E |

|

|

H |

I |

|

E |

|

|

R E D S |

R E D A N E S |

and |

R E D O N |

Deviating from across and down does not mean that these crosswords are not crosswords. It merely suggests that, just as words can currently inhabit spaces above and below one another, the puzzles of the future may place them in front of and behind one another. Which is not really so big a change, is it?

(So, while the crossword remains a physical activity, let us say good-bye to its newsprint form with a pseudoscientific investigation into what your choice of writing device reveals about you . . .)