DIVING THE SOURCE DE L’ÉCOUTÔT

My explorations in the Source de l’Écoutôt started in 2004. On the contrary of the Combe du Creux, they are still unfinished. Each sump has its own difficulties, its own specificities. This one is a tough place where I can also test some material. Of course, it would be meaningless to state something like ‘This cave is one of the toughest I frequent.’ The maximal depth is lesser than inside the Combe du Creux, and one has by far less decompression to pay when coming back. The difficulty is rather related to the length of the sump, about 1,800 metres for the main branch, and to the fact that some sections are narrow or muddy. Parameters are always relative. There exist longer or narrower sumps and muddier caves. If you think that you are the best, it means simply that you have not yet met someone who is better; if you think a cave is difficult, it means simply that you have not yet met a more difficult cave.

As many other sumps of the Doubs, the Source de l’Écoutôt had been more explored than surveyed before I came. My first aim has been to re-explore and make a proper survey; doing première has been a second aim. In order to tell something interesting about this very large project, I have separated things into three parts: the history, the human aspect of things (I mean the psychological and social aspects) and finally an objective description of the cave issued from all the known data.

History: Rise and Decay of Exploration

I dived in this sump for the first time during 2004, and roughly, I never ceased to dive here (Pictures 9.1 to 9.5). Some selected excerpts of a diary are more expressive and faithful than rebuilding the history from one’s remembrances. I added some comments only in order to underline further consequences of the situation or to establish the link with some important external events.

12 September 2004

I lacked of sleep, and as a consequence, I was chilled. I laid 125 metres of my guideline along a pre-existing wire, and when coming back, I made a survey. I will continue with a guideline lighter and cheaper; I will use the one of diameter 1.6 millimetres I had bought for Mexico. Here, one must reckon 10 anchors per 100 metres of guideline. The visibility was quite poor. I spent 49 minutes underground with a mean speed of 10 metres per minute. I didn’t find warm and clear water, and the temperature was 11 degrees Celsius only.

13 December 2004

The weather was very cold, and things turned out to be even more uneasy when I tried to close the zip of my dry suit. I have also had problems regarding other elementary tasks. I dived and followed the guideline, but the visibility was poor: even if I knew that I followed the right line, it was very difficult to see again the details I had seen during the last dives. I laid my guideline along a wire up to its end. Then I followed two ancient guidelines, which were going at left. The visibility has become lower, and I have found a tag with the word bell. After 130 metres, I decided to go back. I had more than enough air, but the visibility had become very poor, and it prevented to continue with a minimal level of safety… . The dive lasted for 78 minutes, and I consumed less than 15 litres per minute. The temperature was more or less ten degrees Celsius. There are different areas with a mixing of surface water and ground water having different temperatures.

14 January 2005

I went in the Doubs with several friends. Diving when I am not alone has become a problem. When other people are waiting for you outside a sump, it is very difficult to forget them and to forget their thoughts once in the cave. It is easier with relatives or siblings than with other people, but it remains difficult. With Denis outside, it was bearable—there were enough confidence and affection—yet it has become very difficult to tell to other people what happened during the dive. The flow rate was higher than during summer dry periods, but diving remained possible. It is very likely that this cave is insulated from the rest of the karst by a breakdown or another obstacle, which limits the flow rate.

Before the dive, the owner of the plot that contains the cave visited us, and I have given him the promised survey I made. Drawing surveys, preparing dives, takes a lot of time. I am no longer interested by the different kinds of meetings specific to the milieu of caving. They cost too much time for a very limited yield.

I dove with side-mounted tanks in order to be flatter in some tough sections. I had to test a home-made buoyancy compensator adapted to my harness. When starting, I felt not at ease: with people around me, I am always in a hurry because I want to escape them and to escape their sight. On the contrary, when I start alone, entering into water after having made efforts is entering into a calm place. Because of the flow rate, the sight in the sump was better than the previous dive. I have had a better understanding of the cave… . Quickly, I arrived to my previous terminus and retrieved the reel I had left. After having observed three divergent ancient guidelines in a place where the visibility was reduced because of the presence of mud, I decided to stop (which meant not laying any guideline this day). When coming back, I measured several sections of the passage. This operation needs to connect a special reel to the main guideline with a carabiner. This small reel has tags each metre, so it allows precise measurements of the passage width. The height can be measured using the indications of the depth gauge. The visibility was sporadic but let me discover what was the morphology of the passage. It looks like a penstock with scallops on the walls. Frequently, it has potholes on its floor. This last detail suggests that in the past, the gallery was not flooded. Sometimes a joint crosses the passage. It looks like a fork, but it isn’t a fork! Outside, Denis and Jean-Luc have prepared a new guideline, measured it and put flags in place. This exercise has avoided them to be too chilled.

19 March 2005

I wanted to dive but didn’t succeed. The stream was increased by snowmelt, and the visibility was too poor (less than 40 centimetres underwater).

2 May 2005

I wanted to dive because the weather was to deteriorate. But I found myself very tired, probably a kind of flu or another virus. So I stayed in our barn, where there was caving material to wash and concrete to prepare. I had also many professional tasks to do.

3 May 2005

I was still ill, but I dived the sump as I wanted. The flow rate was important and visibility was poor, but at least I found the place where I stopped last winter cleaned by the stream. I also found my guideline broken, and I have been obliged to repair it, which has consumed several anchors. I continued to lay my guideline close to one of the pre-existing guidelines or weaved both together. I stopped because of the lack of anchors… . Even if I didn’t reach the safety limits, my air consumption has been important, almost 15 litres per minute. I have spent 75 minutes in the sump, using side-mounted 10-litre tanks and a 9-litre stage tank… . During the evening, I have had a dinner with a friend caver, Didier, and his family. We have discussed several problems of the federation. Between ultra-conservative people and empty-headed people, finding a satisfactory compromise is difficult.

4 May 2005

I dived again in the Source de l’Écoutôt. I was not very fine, and the weather was not very good. But I was longing for a part of the sump I didn’t already know. This is exploration, at least for myself, and exploration is the most important! I have laid less than 100 metres of guideline, but I had the feeling to be very far from the entrance… . I have spent 75 minutes in the sump, and I have been chilled. Thicker underclothes would be very welcome for diving as well as for ‘dry’ caving (when one must wait for other people). I have surveyed a part of the cave that had never been surveyed, and this has been a great happiness.

7 June 2005

I woke up very late and started late. This was a conscious tardiness, for I had to recover. To recover from what? I was weary because at my job, I have been obliged to work with people (some students as well as some colleagues) who were slower than usual. Is it possible to write slow-minded? Their paces were very different from mine… . They are not creative persons, and among them, there are too few women. All that is harmful. I am very young, but I must confess that the dream of being retired has brushed me more than once during the recent nights. This is only a dream, but it would be a pleasure to cultivate roses in the garden of our barn in place of working hard with people who are not hardly motivated… . I started with two 10-litre tanks and a 9-litre stage tank. The weather was warm, with a nice blue sky. The meadows were full of flowers and butterflies. All that was very peaceful and pleasant. The only unpleasant thing has been the effort to pull on the dry suit and close its zip. I sweated, and because of the moisture, I have been chilled later in the sump… . Almost at 120 metres from the entrance, when I finned quietly, I suddenly have been overcome with fear. I have remembered that two years ago, abroad, I got lost in a sump. I was to go out of the cave as quickly as possible, but I tried to have coherent thoughts. I realised that here, the guideline was a firm link between the diver and the entrance. It has the same level of safety than a rope in a pit. This idea allowed me to recover and to continue to dive. I left the stage tank on the guideline at about 300 metres from the entrance before having reached the safety margin. I felt lighter from a moral and physical point of view and was able to continue. Then I recovered my reel and started to lay my guideline.

It is more complicated to lay a new guideline in a sump that already contains a guideline than in a virgin sump. Two other persons had dived in this cave before I came, but the second hasn’t woven his guideline with the first. As a consequence, I had three guidelines to manage. When it was possible, I tried to tie or weave them together. I left many marks on the guideline, which was very slow and very tedious. First of all, such an operation doesn’t allow a good observation of the passage, for one is obliged to focus on the pre-existing guidelines in place of focusing on the natural parts of the surroundings. When coming back, the visibility is always poorer and does not allow to compensate this lack of observation. I laid 300 metres of guideline before stopping it, tying it on the other devoid of tags and cutting it from the reel. The end of the dive has been easier. I went back in more-known places. I was very happy because I did the maximum. I did all what was possible to do. Near the exit, I felt warmer water. It corresponds roughly to the tag ‘140 metres’ of the guideline and to the beginning of a passage that I have to re-explore. This cave is a complex system with many flows. I tried to enter in this passage. It appeared muddy, low; and after 15 metres, I stopped when the pre-existing guideline got trapped in a too-narrow section. After going out of the cave, I undressed under the sun shafts, into the wild nature, and drank an alcohol-free can of beer for rehydration purposes. After that, I went back to Paris, not without bursting a tyre.

An extensive transcription of a diary would take many pages in addition to be boring. I present below only the most representative parts and the widest possible outlook.

6 July 2005

I left the lodge very late after a long sleep with many dreams and the sound of raindrops falling on the roof. I stopped to observe the Puits de la Brême (it is a shaft that can be dry or full of water according to the weather), which was still absorbing surface water despite the rain. It was a good indication regarding the underground flow, and I thought, ‘Very well, the dive will be possible!’

Due to other important recent dives, I hadn’t fully proofed my material, and this is perhaps the mistake that has shortened the dive. After having jettisoned the stage tank, I found myself unable to breathe on the starboard regulator. I didn’t recognise its usual shape, probably because its lid had been unscrewed by rubbing and was lost somewhere in the cave. I didn’t panic at all: I had still two tanks, each containing enough gas to go out. But I have been obliged to stop and go back! By chance, I succeeded to find the lid after 300 metres and even to screw it. I have been able to observe temperature variations in the same place where, during outwards, I saw a very clear-cut separation between clear groundwater and more opaque surface water.

Having no longer regulator problems, I started the exploration of the left bank passage. It was muddy, and a block has possibly fallen after the guideline has been laid by predecessors. It would explain the trapping of this guideline in a narrow section. There was a sensible stream and warm water, 12 degrees Celsius in place of the usual 10 degrees Celsius.

During July 2005

It has rained again. This is demoralising at least because it is difficult to estimate the quantity of water that has fallen. It gives the false feeling that all is rising. In fact, all the sumps are in good conditions. Outside, one isn’t very comfortable when dressing because of the moisture.

Now I know quite well the entrance of the cave and other proximal tough sections. I should try to dive with back-mounted tanks rather with side-mounted material. It should improve my speed in the sump. The French literal translation of ‘using side-mounted tanks’ is ‘to dive in the English fashion’. I should also think to more powerful lights. This is not very useful in muddy water, but sometimes water can be clear! Anyway, buying material costs money. The decision to buy (or not) more powerful lights is a kind of commitment.

I laid 150 metres of guideline. The ancient guideline stopped, and with my ‘light’ guideline of diameter 1.5 millimetre, it was less safe. I found a larger and less muddy passage. I was able to observe several deposits of gravels and laminated clay. This part of the cave has probably had a complex history. When coming back, I continued the exploration of the left bank passage. I had consumed a part of my air, but this passage is close to the entrance. I encountered alternations of warm and cold water, and the visibility turned to be too poor for a proper survey.

Recently, a rival has tried to dive into the cave, and I found a piece of his material near the tag ‘100 metres’ of the first guideline, near the entrance. This is a strange piece of regulator with a male direct system fixed on its hose, probably an element of a rebreather.

Even at the present time, I am very reserved regarding the fact of using a rebreather at place of the main tanks and not ‘in addition’. My personal philosophy is that, in case of problem, it must be possible to jettison the material that has failed and has ceased to be useful. One must be able to try to escape with the rest. It must be noticed that a rebreather flooded by water can create huge problems of balance in addition to the drag and its inertia; not jettisoning it exposes to a huge loss of autonomy. I have developed this philosophy especially during tests in the Source de l’Écoutôt and also because I had read The Sky My Kingdom. As explained in chapter 2, this book has been written by a German woman who was a test pilot before and during WWII, after having started with gliders. She tested the most complicated and hazardous planes of her time. The surroundings are different, but there are also striking similarities with cave diving. There are no numbers, few or no technological tricks to find, in her book. This is something more general, and many stories are interesting also from a psychological point of view. For instance, she explains how she succeeded to survive after her glider got trapped into clouds with a hail storm.

During July 2005

I dove with back-mounted tanks and consumed almost 16 litres per minute; I spent 134 minutes underwater and got chilled. I stopped only because I lacked guideline. I succeeded to avoid getting entangled near the entrance. The places with 12 degrees Celsius warm water have been more than welcome. I measured many cross sections when coming back. In addition to the entanglement, during the measurement of the last cross section, I made a mistake regarding the direction of the exit. Thanks to the tags with arrows, I finned only a short time in the wrong sense and solved quickly this mistake. One of the most perverse effects of cold is that it can alter memory and thoughts. I have already encountered this situation when diving the Grande Fontaine de Sommelonne.

7 January 2006

I looked for a passage between the tags 40 metres and 100 metres of the guideline, but I found nothing.

15 January 2006

After caving with some friends, I prepared my material in order to dive. I had cross sections to measure. Obviously, it is difficult or impossible for some other people to understand what I do and why I do that.

I spent 134 minutes in the cave. I used two stage tanks in order to verify that it was possible to enter into the cave with such a burden. I had prepared a maximum of things in the lodge in order to avoid the cold outside the cave. Nathalie was here, and she helped me to dress. After that, she rolled herself into two sleeping bags; she waited for me and slept. During the beginning of the dive, I have been too hot because of the efforts of carrying two stage tanks in the entrance. My speed was 1,000 metres per hour, which is quite good regarding the morphology of the cave. One can pull oneself on holds only in the first 300 metres of the cave.

It was a long journey, and sometimes I have lost my concentration; thoughts about uninteresting people of the milieu of cave diving have arisen. At a larger time scale, the use of enriched air mixtures rendered the dive very comfortable. The depth is not very important, but spending a long time at -15 metres leads to a certain saturation whatever decompression tables can state. Surveying cross sections is very important. Unknown places are not only in front of the diver but also beside him. Uncanny and unknown territory lies all around. If you get lost, a good knowledge of the shape of the cave may allow you to quickly solve the problem.

When surveying the section that corresponds to the tag 730 metres of the guideline, I have discovered that this part of the passage, which appeared so frightening, has just the shape of a huge penstock with clay banks. The visibility depends on the place. The image of a tiny plane flying through clouds and misty valleys is very pregnant.

After the dive, Nathalie has helped me and has been very kind with me. She knew that this dive was very important for me, and she has done her best. I succeeded to sleep during the first time of the travel towards Paris. After that, I was able to finish to drive our car.

29 January 2006

I made a dive for 190 minutes. I was obliged to stop laying guideline because of the lack of anchors: I let one-kilogram ballast and a carabiner in order to tie the end of the guideline on it. In addition to this première, I surveyed a cross section when coming back at the tag 830 metres. Things that were weird, frightening or worrying have become gradually known and are now a source of happiness. Pretty could be the right word.

The visibility was quite poor (how many times will I repeat this sentence?), and in order to lay my guideline, I followed a clay bank aside the passage. Lying guideline when doing première changes the fashion to ‘read’ the cave. As aforementioned, the attention devoted to pre-existing guideline can be fully dedicated to the cave itself. From a mental point of view, a good balance must be found. Being too reserved is good for safety, but this does not allow to make the maximal première, whereas being too euphoric is good for the première but not for safety.

I am very happy!

This dive was a great source of satisfaction and strongly contrasted with federal and politic problems in which I was still involved. A few times after this dive, I participated a meeting in the house of one of the cave divers from Paris region. It was a meeting about cave diving rescue.

Rescue should, in principle, be one of the more selfless activities of caving. But here, a crude rivalry appeared. I was on one side, and the other cave divers, all from the same club, were on the other side. All my forecasts have been confirmed by the issues of the meeting and the fashion it took place. Some people—all from the same club—were present despite the fact they did not answer to the email invitation. They also did not answer to the emails I had sent related to the conception of a cave diving rescue exercise. They just criticised it during the meeting. The planned agenda has not been followed during the meeting. This was very probably a fashion to try to destabilise me.

Those people have tried to impose their views during the whole meeting in place of fair negotiations, discussions and suggestions. Nobody has criticised my level or my abilities. I was criticized exclusively regarding the form and the appearances. They reproached me for not having respected very vague rules that they didn’t respect themselves or that they had freshly invented. They even had more incredible reproaches on the fact my emails were not easily readable, which is totally false. I am very careful regarding this aspect of things, and I always structure and proof the text. Were they not able to use their own computers? They also pretended that they didn’t understand what ‘doing the survey of a sump in order to look for a missing diver’ meant. This is very strange, though one of the divers has made a lot of surveyed explorations. Perhaps he wanted to please his ‘friends’? Eventually, they refused the use of gas mixes (mixes containing more oxygen and less nitrogen than air) for the exercise, which is against the most elementary safety regarding decompression!

Even years later, I am still unable to choose between the two following explanations:

- - Perhaps they were really short-sighted. Perhaps they didn’t realise that their ideas, very well structured at a short scale, were totally contradictory at a larger scale.

- - Or perhaps were they totally aware of what they did. Perhaps they regarded cave diving rescue as a tool of power among other tools of power. And if this explanation is the right one, what kind of power did they expect? At least, this event has provided me a new view of what they were: a social class whose power is linked neither with personal competences nor with personal understanding. Their power is only linked to the network of relationships they can establish or to the image they can give. Anyway, I think cave diving is a serious activity. This is not a sandbox. This is not a place to reach the social level one is unable to reach in other parts of life. In a sump, you are alone to solve any problem and to find the exit; your only power is material and intellectual. Hence, of course, I have resigned from this kind of cave rescue. I still regret (again, cave rescue should be selfless), but at least, it is impossible to crush someone if he is not in the proper place to be crushed. I will never go back to cave diving rescue trainings.

13 October 2007

I started for the première. Two 12-litre stage tanks were in the sump since the last summer. In addition, I started with a 10-litre stage tank and another one of 7.5 litres. I wore thick underclothes, so I found myself too cold when starting. The visibility was very good, and sometimes I was able to see for the first time the sections of the gallery exactly as I had drawn them. I finned quickly, at ease.

I found the foam on the stage tanks (it lightens them) crushed by more than two months of immersion. Once arrived in the ‘deep’ zone, I found myself slightly stressed. It was more than 1,000 metres far from the entrance, and the only guideline was mine. But all was OK, and I was able to progress … until I found a ball of guideline. Because of the flow enhanced by the rainy days of autumn, the guideline has broken and has drifted. This was problematic because I found myself unable to use the reel I had left at its end. I have just a safety reel, and if I used it, I would then be unable to solve any further problem. But I found quickly another solution to this vital problem. I tied this ball with rubber bands in order to stop the process, and I went back, relieved. I needed probably a ‘blank’ dive in this remote area for a better habituation, and that is exactly what happened. I came back at ease and was even able to measure two cross sections. I succeeded to bring out all the stage tanks. They were quite cumbersome, but the most difficult has been to remove them once outside in the very shallow water of the entrance.

2 November 2007

I dove in order to carry stage tanks at the right place. I made many pictures with my waterproof camera. I observed a ‘paragenetic channel’ in the ceiling of the passage not very far from the entrance. During its history, the gallery has probably been totally filled with silt. Water created itself a pathway above the filling.

4 November 2007

The sky was overcast with grey clouds, something that was partly mist, partly drizzle. Nevertheless, the hydrology remained perfect for the première. I started again with two stage tanks and worn my old seven-millimetre-thick neoprene dry suit. The weather was cold and allowed a painless, sweat-less dressing.

Farther, the water was still very clear, and I progressed very easily. Sometimes I was able to fin at almost 20 metres per minute with the stage tanks! Just at the beginning of the deep zone, I jettisoned the fore-last stage tank and used the last full of 50 % oxygen mix. It diminishes the saturation and avoids any decompression stop. I jettisoned also the flask I carried after having drunk half of its content. It was full of pineapple juice, very good for rehydration and sugar intake. I was no longer hot when I arrived on the ball and tied on my new reel. I progressed. It went up. It turned. It ended 80 metres after the beginning of the new guideline. I was at the ceiling, near what seemed to be the left wall of a passage, with a little dome aligned with a joint. I decided to stop here, for the level of risk had increased. The visibility had vanished. I was in a non-already-known passage, and it was far from the entrance. I left a piece of ballast and a peg as anchors. Cutting the guideline and tying it on the reel has been a very delicate operation. It took me as much time as the 80 metres of exploration.

Sometimes the visibility was awful, but I did my best to make notes. Without measurements and without survey, my incursion and the risk would have been meaningless. I found back the last stage tank and the flask, and I finned. The visibility improved only in an area that contains fallen slabs. Unfortunately, I have been unable to take pictures. My camera hadn’t enough autonomy. I found back the other stage tanks and finned. Except the hands, I was not cold. I decided to continue to drag all the stage tanks despite the fact they slowed me down. Again, the visibility became poor, and I found myself obliged to use other senses than sight. I went out without further problem despite the flatness of the entrance. I removed my equipment, undressed, drank what remained in the flask and carried the material back to the car.

I went back to the barn and thought to all that when driving. I thought to the life that flows, to all what I had to do. The directions of the passage seemed to change. Perhaps it stopped on the hypothetical boulder, which would limit the cave’s flow rate. It would be coherent with the presence of mud, but I have no other evidence.

Up to the present time, I never succeeded to come back to this terminus because of several reasons I explain in other parts of this book. Thus, I don’t regard the exploration of the main branch of the Source de l’Écoutôt as a past work. After 2007, I continued to dive and to make notes.

30 July 2008

My goal was to find a secondary passage and to take pictures with a new camera. But I was ill. My sinuses were blocked, and below -2 metres, it was too painful. I gave up.

29 September 2008

My goal was to do some observations and to explore the passage I have named Bingo-Crépuscule, which is at right when going inwards. In this passage, the visibility was better than the last time I visited it. However some sections were narrow or flat, and sometimes the guideline was difficult to catch.

The entrance zone is quite chaotic. It seems that in an initial wide bedding plan (gap between two horizontal strata), passages looking like penstocks have developed, led by joints (vertical very narrow cracks.) All that looks like a delta. Farther from the entrance, the same configuration can be seen again. Before the beginning of the Potholes Gallery (Galerie des Marmites), it is possible to see something wide with many irregular rocky shapes.

I have had also a look on a second secondary passage, which is also at right when going inwards. It looks like a small flooded meander. Just before the first known bell, at almost 400 metres from the entrance, I have found another new bell.

After this dive, I have continued the exploration of the Bingo-Crépuscule passage. At the end of this flooded zone, one finds a ‘dry’ zone. Using a rope, it is possible to drop down in a kind of cone full of muddy water. I know its depth only because my timer has recorded it. The visibility was too poor during the dive. It is ten meters deep or slightly less if one takes into account the fact that mud is denser than water! The name Bingo-Crépuscule is issued from the film Un Long Dimanche de Fiançailles with the actress Amélie Poulain playing one of the characters, because it is a tough place.

I have begun several rebreather tests in the cave during 2009. Except those tests, 2009 and 2010 have been years of depression regarding my explorations here. I have started again serious things in 2011, but things turned to be less easy than at the beginning, in 2004. I already knew all the ‘easy’ parts of the cave that are close to the entrance, and I had no longer the satisfaction of discovering them. More exactly, it is more difficult to be in the mood of discovery. This kind of satisfaction is the basis of the progression that allows step by step to reach the farthest point of the cave. In the same cave, one cannot benefit twice of this kind of help. Therefore, from the moral point of view, preparing an incursion in order to reach the terminus is less easy. Regarding weather too, some years are better than others. In addition, the cave slowly evolves, and I find regularly more silt and mud deposits in some places. Wholly speaking, the visibility has become worse. For instance, I have installed two stage tanks in the sump during August 2013; and more than 15 months after, I have not yet found the right conditions to go farther.

Human Aspect of Things, Violence and Social Evolution

Up to the present time, I regard this cave not only as an object to be explored and surveyed. It acts also as a kind of mirror. It throws back an image; it helps me to develop thoughts and considerations about my situation and to define or solve some of the problems I encounter with other people. Very often also, it helps me to have a very remote regard on our modern age and to precise my ethics. It is one of the places that sustain my personal development. This is because it is a long cave; it requires finning during a long time, and so it allows thoughts to develop. This is also perhaps because it has tough sections. Once known, passing them enables the distraction and thoughts that would have been forbidden to other people encountering them for the first time.

This cave helped me to realise that in our occidental civilisation, many people are in trouble because they have ideals, role models, which are practically unreachable. An extreme caricature is perhaps the case of black women who want to become blonde because ‘one’ has presented the blonde women as perfection. They want to reach that perfection, oblivious of their original beauty, and they fail. When diving in the Source de l’Écoutôt, I have realised that one must have one’s own ideals and avoid to believe in other people’s ideals. To a certain extent, if you believe in the ideal of another person, you give to this person a grip and power on you. This is a kind of alienation, and it is of first importance to avoid it.

Anyway, I like this cave very much, and I don’t give up whatever other people’s opinions. When I insisted on the gas consumption and other parameters in my diary, I was probably worried by a possible competition with other people. Indeed, competition was not only about première but also about pointless things, which can build the image of someone. Those pointless things conceal frequently a huge violence to such an extent that I dare to do a comparison with WWI. Things look also like WWI because of the mix of material and pristine nature, and because the days before have irreversibly gone (this is a milestone for the road to modern age).

I’m not the only who thinks of a link between development and progress on the one hand and violence on the other hand. The famous philosopher Hannah Arendt reflects about that, especially in a chapter entitled ‘Tradition and the Modern Age’ of his book Between Past and Future. The idea that days have irreversibly gone is valid at the scale of the whole human history as well as at the scale of any person who remembers his/her own childhood. Childhood affords time to dream and to transform the world, as well as time to enjoy trouble-free long summers. After childhood, summer is always too short and dreams too scarce.

Of course, the likeness with WWI is a very partial one: cave diving is a pacific activity. On my side at least, there is no enemy to eliminate in order to reach a goal. In addition, the hierarchy of caving is the one of a whole society (not the one of an army that couldn’t exist by itself). In principle, elections and democratic processes exist among clubs and federations.

However, some facets of cave diving are very close to the heroic face of warfare, and the word tank speaks by itself. From the point of view of words, sounds and images, many other objects are related at the same time to warfare and to cave diving. The cave diver has a helmet with lamps at place of its panache. The suit he wears can be seen as an armour. The equipment process, before entering into the sump, is sometimes very complex and takes a lot of time. The diver wears a lot of material, and outside water, he is too clumsy to move easily by himself. This can be compared to the situation of a medieval knight helped by a squire before riding his warhorse. All that is related to pure chivalric values even if the warhorse has disappeared. It is superseded, sometimes, by a propeller. However, using a propeller is different to ride a warhorse. A better comparison could be made with the steering of an aircraft.

Even if chivalric values and heroism are still perceptible, cave diving is closer to modern and technological war, where you don’t have a total control over things and processes. Tanks used for diving are full of gas under pressure and can sometimes burst. They are filled with a mechanical compressor. It is a noisy machine that sings like a motorised vehicle or an aircraft. Stage tanks can be carried along the sump or jettisoned. There exist pictures showing a team posing near the heap of tanks needed for the successful exploration. Such a picture isn’t very different from a heap of shells or bombs.

Most people are unaware of that modern values. When reading specialised magazines, the image that appears beyond the text is only the heroic one. The successful exploration is the result of only one man, the diver who has made the première. There exists a team that has sustained him but only sustained him as the medieval squire served the knight. When prevention has not well worked, or when fate kills, one can even think of earlier moments of human history such as the Iliad and Odyssey or northern sagas. When a diver dies during cave diving, one finds often in some specialised reviews a kind of panegyric where his life and the fashion it has ceased are presented as a whole adventure. Frequently, a kind of underlying dramatic logic perspires as if all that was planned in advance. This can be regarded as a fashion, more developed than a simple première, to make the unlucky enter in the collective, perennial and universal history of cave diving.

I think that heroic images are not very interesting regarding prevention. More precisely, regarding cave diving commissions and editorial boards, it is quite paradoxical on the one hand to do prevention and on the other hand to subscribe to such a heroic scheme. Is it conscientiously done? This apparent image is also very different from the organisation that allows cave diving to be possible. It is true that the diver who leads the team and the diver who makes the première are often the same person. It is also true that this person cannot be changed, whereas the members of the team can be easily changed, added or removed. Nevertheless, few premières made with a team would remain possible without it.

I’m not very at ease with people who stand in between the situation of doing things alone with the corresponding consciousness and the situation of managing things at the size of a school, a plant or another big system. I think that either the results belong either to the whole team or there is no team. I have already written several times that I prefer caving and diving underground alone. It is foremost a fashion to escape from this modern social world I don’t like. But even alone, the encountered feelings, moods, sensations and rhythms are far from the realm of chivalry and heroism. This establishes another link with WWI. The proportion of time devoted to pure action is not very important, and a higher proportion is devoted to repetitive tasks of maintenance and preparation—to ‘routine’. One has to earn money, and one has to cope with ordinary everyday life when it interferes with caving projects. So in order to practise the true cave diving (the one that does not belong to newspapers and volatile information), one must be able to cope with stalemate during long periods of time as well as short moments of intense emotion and fear. It happens more or less frequently that a well-prepared incursion has to be postponed or cancelled as described above. Often, this is because the weather or the underground hydrology is not good enough. Sometimes it is simply because of weariness. It also happens because of technical problems, lack of visibility or weariness, that one has to come back to the exit of the cave without reaching any interesting goal. In comparison with other sportive activities, a lot of money, time and other resources are spent for a random yield.

The underground world is not so beautiful as the specialised reviews depict it. Regarding material and human optimisation, if you can see a person on a picture, it means that at least two persons were present. If you can see a large sump well lighted, it means that flashes have been installed. This cannot really correspond to the conditions of an engaged incursion. Regarding aesthetics, in dry caves as well as in sumps, the walls are more frequently covered with mud than with beautiful concretions. Generally, filthy is a more proper word than gorgeous. Diving in the total dark can be a challenge for a cave diver during a training session in order to show his motor ability, especially if he is sure to be able to turn on the light at every moment. Such an exercise is described in many texts. But during real cave diving, the visibility is different from the pure transparency of aesthetics and from the pure darkness of the texts. This is like moving in a more or less thick mist, where you have just enough visibility to see around you and not enough visibility to really see the surroundings. This is the main reason why diving alone is safer. Tightly following the guideline is compulsory as well as boring. When the visibility becomes lower, you have both hands on the guideline, and you are totally unable to turn on or off your lights as during a training session.

Some authors have written or said that in the trenches of WWI, there existed a permanent roaring sound that held each man at each time. They also reported that senses were more governed in an instinctive fashion by sound (they were less governed in a rational fashion by sight). With tanks as well as with rebreathers, this is exactly the same kind of situation. Some sounds mean ‘Incoming serious problem. Act and protect yourself immediately!’ Other sounds are on the contrary very impressive but don’t correspond to a real danger. For instance, air flowing along the ceiling can generate very strange noises. Darkness seems to be characteristic of underground worlds, and a book is even entitled Darkness Beckons. Nevertheless, my own opinion is that underground, you carry with you a dim permanent light that allows you a very partial sight. This is more likely comparable to the absence of darkness of some battlefields of WWI; they were lighted by flares even during night. Light and sound stop only when the war ends.

Lack of sleep and time shift, which were present 100 years ago, are also very present in my caver’s life. I do not think of the small-time shift due to the dozen of minutes or hours spent underground. Doing one’s job in an honest fashion and at the same time practising caving means that you are obliged to steal moments from your body and from your spirit. You have less time to let your body at rest. You have less time to dream during a shortened sleep. Sometimes it means working hard during a part of the night in order to scan maps, find information or build material. For the same reason, some weekends are devoted neither to action underground nor to rest. They are periods of non-paid job between two periods of paid job. Sometimes one has no other possibility than choosing between a proper physical training and enough rest; this is very demoralising, being able to bear all that is essential, and it is very far from chivalry. This is mostly a modern and economic warfare, where many essential choices must be done. For instance, would you buy a mattress or a new regulator?

Eventually, I want to confess an important reason to practise cave diving and to continue to practise it. I need a kind of balance between moral and physical violence. I regard our current world as something morally very violent because it is disappointing and devoid of real meaning. Very often, people act as if they were following a general logic that should be imposed on anybody. But in reality, they scarcely have a firm internal logic beyond their short time-scale egoism. I do not know if the proper word to call the health problems I had had during a period of my professional life is burnout or shell shock. Even if physical violence is prohibited, and despite the politeness of language, I think that our world is too coercive. This is the origin of its moral violence. In correlation, I think it is totally blind from a moral and organisational point of view. Many easy and costless optimisations or adjustments that could render a lot of people happy are not done. We are trammelled with a lot of rules and regulations that have lost their practical basis. They have become a world by itself, which isn’t the real and physical world.

A lot of resources are lost by static rules, lack of perspicacity and conformism. Therefore, I need another kind of violence in another part of my life in order to balance. Caves are the essential resource that allow me to develop and keep for myself the physical violence I need. Underground, if you do things alone, you owe any failure or success you encounter only to yourself. It is simple and devoid of any ambiguity. You can choose to do the optimisations you want, and you are the only responsible for the results. You can follow your own way and behave according to your own logic and your own moral values. In addition, nobody has to receive the violence you developed, which is wonderful. It must be noticed that violence and risk are two different things.

On the contrary of certain other cave divers (as well as certain soldiers, as described for instance by Siegfried Sassoon in his pseudo-autobiography The Memoirs of an Infantry Officer), I never take too much provisional risk. I have no motorcycle licence, I drive slowly my car, and I’m probably not regarded as the boldest man among cave divers.

Cave diving is my fate even if I strongly counsel to people who can choose their fate to choose another activity. There exist other open-door or artistic activities that are not submitted to the same stalemate and that give at least the same physical or intellectual satisfactions. If one is looking for that, they can also be very complex and technologic. Climbing and artificial climbing are one of the numerous possibilities, especially if one tries to avoid indoor climbing walls. I dare to write what other cave divers don’t write too frequently. I do cave diving only because I am less able to succeed in another activity. There is no military medal for doing cave diving, and even première cannot be regarded as a reward. The only reward, which is very cumulative, is to be still alive and not getting lost somewhere between front and home.

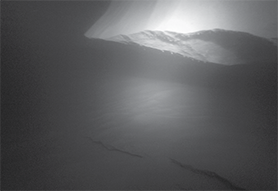

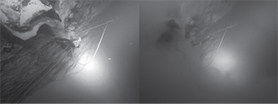

Certain divers are able to lie and boast. It seems to be compulsory if one wants to remain ‘well-known’. Instead of exaggerating things, I prefer to consider the low visibility (Picture 9.18) I described above as a metaphor of our terrestrial everyday life. It means ‘life at job’ or ‘out of caves’ realm’. Very often, we are blinded or trammelled by some problems we have contributed to create. Even if volatile and boring, these stupidities have an important and sustained impact upon our social life. If we would be able to lift our head, we could get a larger, cleaner and stiller horizon. The metaphor with the smog encumbering our mind is obvious too. We must save ourselves by developing deeper, wider and more abstract thoughts. (There is a trend, at least at my job, to avoid anything that would be conceptually too deep!) This second metaphor leads to cave intelligence. For instance, each gloomy measurement made underground becomes, once in the computer, a piece of a clearer survey. (As suggested in chapter 4, nothing is possible outside the concept of survey.)

Diving in this cave has always been a fashion to reconsider my social outlook. In addition, it is often a poetic exercise. This adds to the very material and objective data I want to bring back. Yet this does not supersede them. By ‘poetic’, I mean mainly the philosophy that is concealed inside aesthetics. When I’m going from my barn to the cave, I’m very close to the landscape. Once, I made the following notes in my diary:

The blue sky has crumbled away, leaving white clouds. It has rained. Then the rain has stopped. Now, a decreasing sun comes again. Its shafts are lighting the mist, drifting over the warm road, or they are going astray in the deep green woods on each side. This whole ‘green’ ranges over many undertones. There are the very light undertones of lit leaves. They contrast with the stronger green of leaves beneath the shadows. Some scientists, astronauts or cosmologists say that blue is the colour of life. Indeed, from space, Mother Earth appears blue because of her water. But I am persuaded that green is the true colour, which deals with life. Would it be anything alive without chlorophyll? In some African countries, the main colours are a deep blue sky and an ochre soil. But always green dashes point out life. And if you dive in the Atlantic Ocean or in many other places, the main colour is green again because of tiny algae and other living things. Yes, ‘green’ is a strange colour, and entering in ‘green’ is entering in another world. When colour is present, many pictures taken inside the Source de l’Écoutôt are seized by the green tinge too. All that is very far from the azure, one can find when diving under ice or in some Caribbean places. Is it a liquid forest whose only solids remains are tales?

Having green leaves near the entrance of the cave shows clearly the border between peace and war, technology and nature. I also made more social notes:

Development is wealth only if it is adapted to who is to develop. Aims, techniques and teaching of caving and cave diving can be regarded as development, so the previous idea applies to them too. Very frequently in our Western European world, development is imposed to people by means of sundry constraints. This isn’t often a personal process of continuous improvement. The basic dogma assumes that only one kind of collective development is the best, regardless to who is concerned. Other people have just to follow this development. Of course, they are neither supposed to forestall it nor to ‘take what is good and let the dregs’. Whatever the price to pay, I refuse to enter this frame where the worst addiction is to want to resemble to other people. If fairies exist underground, my muse of sumps has probably long dark hair, brown eyes and a lightly tanned face.

Consistently, I think of all that when I find the first hundred metres of the sump. I think also to people with whom I have had problems. As a caver, it can happen to be despised by people who don’t understand what you are doing. Once outward, I turn to a strange mood, realising that one is able to be here in addition to the other terrestrial things one is able to do. This is a release. There has been violence but just something physical. This balance is necessary to bear the extreme moral violence of our common terrestrial life. All that gives a deep subjective beauty to this cave I love and often dreamt of. My mind is never far from ancient poetry, for instance Blake’s ‘Angel’:

I dreamt a dream! What can it mean?

And that I was a maiden Queen

Guarded by an Angel mild:

Witless woe was ne’er beguiled!

And I wept both night and day,

And he wiped my tears away;

And I wept both day and night,

And hid from him my heart’s delight.

So he took his wings, and fled;

Then the morn blushed rosy red.

I dried my tears, and armed my fears

With ten thousand shields and spears.

Soon my Angel came again;

I was armed, he came in vain;

For the time of youth was fled,

And grey hairs were on my head.

The non-poet that I am could reply to his verses by a short prose: where is the difference between dream and reality? The man I am is often obliged to be his own guardian angel, and my only true sorrow is to be obliged, sometimes, to be far from karst and caves. It happened I shed tears in my mask during some painful tests of material I couldn’t suddenly stop. It is true that I no longer see some people I frequently saw in the past, when I was young. It is unavoidable that my hairs turn white.

Objective Elements

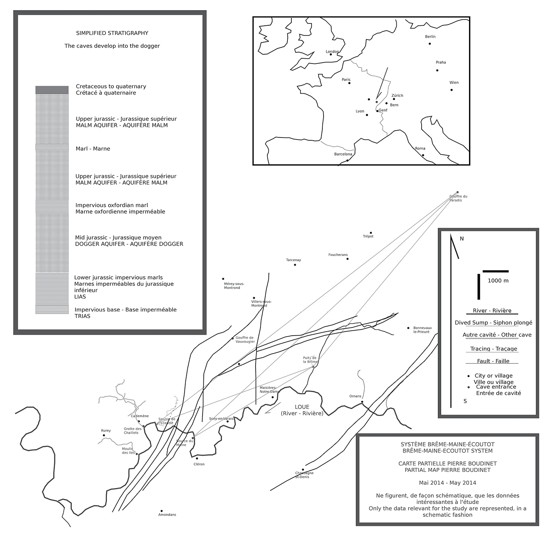

Before ending this chapter, I would like to give a material description of this cave, which is a very real object. Otherwise, all my efforts would be worthless and meaningless. It is located in the east of France, in the department of the Doubs, which is a part of the geographical Jura. Its coordinates are 47°05’57” N and 06°02’20” E. This cave is a part of a hydrological system presumed very large. It includes other sumps such as the Source du Maine and the Puits de la Brême. A link is presumed with the water that flows in the bottom of some caves of the plateaus above (Picture 9.6). I dived a lot in this cave, but I have also surveyed the Puits de la Brême and other caves alone. Together with Denis Langlois and other friends, we have re-explored the Gouffre du Paradis, dived its sumps and found new things. Here, I focus only on one cave.

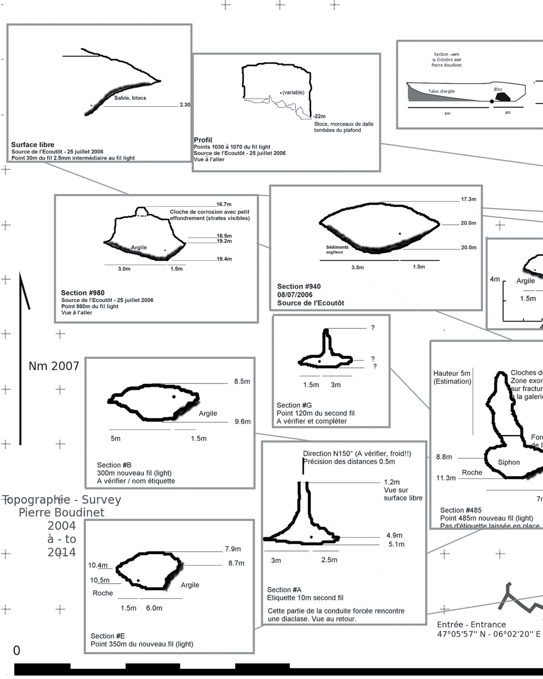

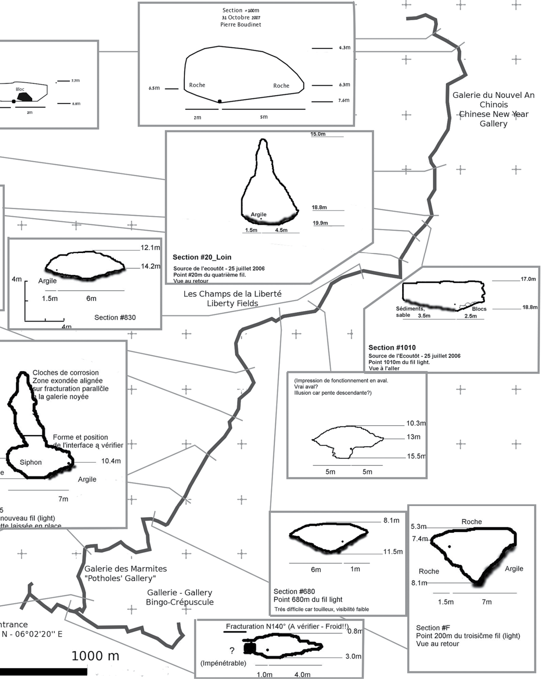

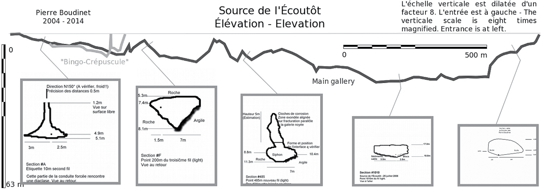

The whole shape of this cave can be seen on a map (Picture 9.7). Knowing the directions, lengths, widths and heights of the galleries is necessary to know the cave, although it is not enough. The survey has been made underwater and alone. Hence, its precision corresponds to the degree 3B of the British Cave Research Association. It is interesting to describe some shapes and sediments that can be found at different places inside the cave. This adds a minimal geomorphological understanding to the raw shape. The entrance itself is very rich. One can peer (Picture 9.8) the two main directions of weaknesses of the bedrock roughly at N 017° (athwart the entrance) and N 115° (quite along the entrance). These directions emerge also from the direction diagrams resulting from the survey. Eventually, NNE direction appears also (Picture 9.6) to a privileged direction for faults. After the entrance flat narrow passage (Picture 9.9), one can observe scallops and flutes (Picture 9.10). I presented briefly such wonders in chapter 8. The entrance looks like an underground delta formed in the main bedding plane. There are other impenetrable outlets, for instance just on the actual bank of the River Loue at 47°05’56” N and 06°02’18” E. This part of the cave is flat, larger than high.

At about 120 metres from the entrance, one finds a fork. We continue with the left gallery, which is the main one. After this area, one finds a different shape. It has been called the Galerie des Marmites (Potholes Gallery) by the first explorers. Sometimes it presents curved grooves, which can be interpreted as former meanders, and one can find many large flooded potholes (Picture 9.11). They suggest this part of the cave has not always been a sump. Corrosion seems very active; one can find again scallops and other dissolution shapes. At about 375 metres from the entrance, the morphology changes again. One finds a mud slope located under a bell. It has not at all the shape of a church bell and looks rather like a part of upper gallery. Then the sump develops deeper after this interruption. The depth varies, but all details suggest that without the bell, there had been a slow regular descent from the entrance. The presence of a bell suggests a former breakdown, acting as a boulder (Picture 9.12).

Blocks of mud have fallen on the guideline between successive dives (Picture 9.13). They indicate that in some places there is also mud at the ceiling. It is very likely that such a deposit formed during a series of episodes where the cave was alternatively totally flooded or not. Perhaps in a past epoch, it was a sump only during rises after rainy episodes. Other deposits indicate a complex evolution of the cave. One can find in several places successive beds of sediments of variable graining. The coarse ones are pebbles of size of order of the centimetre (Picture 9.14). They have been transported by only a non-flooded stream with an important velocity that can transport such pebbles. The succession of beds indicates repeated variations of speed. Seasonal variations during a glacial era are a possibility. At about 500 metres from entrance, one finds a weird place where ribs are present (Pictures 9.15). It is admitted that ribs cannot form in flooded surroundings. This is an additional evidence that the cave, at least from the entrance to this part, has not always been flooded. At about 840 metres from the entrance, one finds again the same kind of morphology than at 350 metres. There is a bell with a breakdown, and the sump is temporarily shallower. (The free surface can be seen, and it is difficult for the diver to keep a proper buoyancy and balance; it would a possible temporary shelter in case of problem, for instance to repair a regulator).

After this bell, one finds again variations of depth and many mud banks (Picture 9.12). The visibility (Picture 9.18) is often poor up to 1,200 metres from entrance. Then one reaches a deeper part of the sump (Picture 9.16). There is few or no mud, and the section is rectangular with slabs fallen from the ceiling. The clearer groundwater, as well the morphology, suggests that this part of the cave has always been a sump. After several hundred of metres, the sump becomes shallower again and muddy again. The current terminus is shallow (-3 metres). Sometimes the lack of proper natural anchors has obliged to ballast the line with small pieces of lead (Picture 9.17). It has not been possible to see clearly something. A possible hypothesis is that the penetrable conduit encounters a breakdown that trammels the flow. This would explain the mud. Perhaps this breakdown is penetrable, or perhaps it is not.

I have re-explored the Bingo-Crépuscule zone at right and 120 metres from the entrance. It has some narrow parts, and there is a bell. This branch ends in a ‘dry’ place. In this place, one finds a kind of muddy waterlogged crater, having a depth of about 10 metres. It is interesting to superimpose the survey on a geological map (Picture 9.6). Except the entrance zone, the sump is aligned with the main fault direction. The Bingo-Crépuscule gallery suggests that faults can lead the cave as well as limit it.

Picture 9.1: The Source de l’Écoutôt is tributary of the river Loue. This is a green and remote place where Nature is still the Queen…

Picture 9.2: … It strongly contrasts with what can be found inside the cave. Exploration cannot be made without technology; after having made the photograph I have removed this very big and heavy reel left by the predecessors.

Picture 9.3: During rainy weather, the cave rises and cannot be dived.

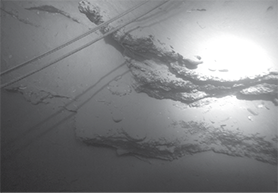

Picture 9.4: Water appears still but isn’t, for the photograph has been made without flash. There would be no visibility inside the sump.

Picture 9.5: (Courtsey of Nathalie Boudinet) This cave is quite shallow but a lot of material is needed. The weight of the four tanks (about 60 kg) is balanced by Archimedes buoyancy, but drag and inertia remain!

Picture 9.6: Location of the caves and geological details.

Picture 9.7: Plane view of the Source de l’Écoutôt. Because of the amount of data, it is convenient to start from each section to find its location, rather than starting from the location to the section.

Picture 9.8: Entrance of the cave and fracturation directions N017° and N115°. Inside the cave, they very frequently lead the gallery. Upper right one can see two directions diagrams. The proper one contains 30° classes compatible with measurements precision. The other illustrates how false statements could be made without proper mathematical considerations

Picture 9.9: Beginning of the sump. This is a flat narrow part where one has to find one’s way with the guideline sometimes in one hand and sometimes in the other one.

Picture 9.10: Scallops and flutes inside the Source de l’Écoutôt. The height of the stratum is about one foot.

Picture 9.11: A flooded pothole hollowed out inside another larger flooded pothole whose size is almost 2 metres. This part of the cave has not always been flooded

Picture 9.12: Elevation of the cave. It suggests that several breakdowns occurred, acting as boulders. The vertical scale is exaggerated eight times.

Picture 9.13: A block of mud fallen on the guideline. It suggests deposits of dry clay above, at the ceiling.

Picture 9.14: Layers of pebbles. The stream was strong enough to transport them after what they have been cemented perhaps during a dry episode. This suggests anew this part of the cave has not always been flooded.

Picture 9.15: Ribs. They suggest this part of the cave has not always been flooded.

Picture 9.16: Picture taken during action, which explains its fuzziness. Inside Les Champs de la Liberté (“Liberty Fields”). Its real size is about 2 metres.

Picture 9.17: Small pieces of ballast used as anchors, far from entrance.

Picture 9.18: The visibility can easily vanish. The interval between the two photographs is about 3 s, then I left my camera and took the guideline with both hands.